Validating Epigenetic Biomarkers for Early Cancer Detection: From Discovery to Clinical Implementation

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the validation pipeline for epigenetic biomarkers in early cancer detection, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Validating Epigenetic Biomarkers for Early Cancer Detection: From Discovery to Clinical Implementation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the validation pipeline for epigenetic biomarkers in early cancer detection, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. We explore the foundational biology of DNA methylation and other epigenetic marks as promising cancer biomarkers, detailing advanced methodological approaches from bisulfite sequencing to AI-powered analysis. The content addresses critical troubleshooting aspects for overcoming technical and biological challenges in biomarker development and establishes rigorous frameworks for analytical and clinical validation. By synthesizing current evidence from multi-cancer early detection tests and novel epigenetic networks, this resource aims to bridge the gap between biomarker discovery and clinical implementation for precision oncology.

The Epigenetic Landscape in Cancer: Mechanisms and Biomarker Potential

Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) methylation represents a crucial epigenetic mechanism that regulates gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence. This process involves the addition of a methyl group to the 5-carbon position of cytosine rings, primarily within cytosine-phosphate-guanine (CpG) dinucleotides, resulting in 5-methylcytosine (5mC) [1]. In normal physiological conditions, DNA methylation plays fundamental roles in embryonic development, genomic imprinting, X-chromosome inactivation, and maintenance of genomic stability by suppressing transposable elements [1] [2]. The establishment and maintenance of methylation patterns are catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), with DNMT3A and DNMT3B responsible for de novo methylation, and DNMT1 maintaining methylation patterns during DNA replication [1] [2].

Cancer cells exhibit profound disruptions in their DNA methylation patterns, characterized by two hallmark alterations: global genomic hypomethylation and focal CpG island hypermethylation [3] [4] [1]. Global hypomethylation promotes genomic instability and can activate oncogenes, while promoter-specific hypermethylation leads to the transcriptional silencing of tumor suppressor genes [4] [1] [2]. These alterations emerge early in tumorigenesis and remain stable throughout cancer progression, making them attractive targets for biomarker development [5] [4]. The dynamic interplay between normal methylation regulation and cancer-associated aberrations forms a critical foundation for understanding cancer biology and developing epigenetic-based diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

Molecular Mechanisms and Technological Approaches

Enzymatic Regulation of DNA Methylation

The DNA methylation machinery consists of "writer" and "eraser" enzymes that establish and remove methylation marks, respectively. The DNMT family functions as writers, with DNMT3A and DNMT3B establishing new methylation patterns during development, while DNMT1 maintains these patterns during cell division by copying methylation marks to the daughter DNA strand [1] [2]. Active demethylation is primarily catalyzed by Ten-eleven translocation (TET) dioxygenases, which sequentially oxidize 5mC to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), 5-formylcytosine (5fC), and 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC) [1]. These enzymatic processes ensure the dynamic regulation of the epigenome in response to developmental and environmental signals.

In cancer, this precise regulation is disrupted. Aberrant DNMT activity leads to hypermethylation of tumor suppressor gene promoters, while impaired TET function contributes to global hypomethylation [1]. These changes create a permissive environment for malignant transformation by silencing genes involved in cell cycle control, DNA repair, and apoptosis, while simultaneously activating oncogenes and transposable elements [1] [2].

Analytical Technologies for DNA Methylation Assessment

Advances in methylation profiling technologies have revolutionized our ability to study epigenetic dynamics in cancer. These methods vary in resolution, throughput, cost, and application suitability, enabling researchers to select approaches aligned with their specific experimental goals.

Table 1: DNA Methylation Analysis Technologies

| Technology | Resolution | Throughput | Primary Applications | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) | Single-base | High | Discovery, comprehensive methylome analysis | Gold standard for base-resolution whole methylome [5] [2] |

| Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS) | Single-base | Medium | Targeted discovery, CpG-rich regions | Cost-effective; focuses on CpG-dense regions [5] [6] |

| Methylation Microarrays | Single CpG site | High | Biomarker validation, large cohort studies | Cost-effective for population studies [5] [2] |

| Nanopore Sequencing | Single-base | High | Direct detection, long reads | No bisulfite conversion; detects modifications natively [5] [2] |

| Quantitative Methylation-Specific PCR (qMSP) | Locus-specific | Low | Clinical validation, targeted analysis | High sensitivity for low-abundance targets [5] [7] [2] |

| Pyrosequencing | Single CpG site | Low | Validation, quantitative analysis | Quantitative accuracy for specific CpG sites [2] |

The choice of methodology depends on research objectives, with WGBS and RRBS preferred for discovery-phase studies, while targeted approaches like qMSP and pyrosequencing are better suited for clinical validation of specific biomarkers [5] [2]. Emerging technologies such as nanopore sequencing offer particularly promising applications for liquid biopsies, as they enable direct methylation detection without chemical conversion, thereby preserving DNA integrity—a critical consideration when working with limited quantities of cell-free DNA (cfDNA) [5] [2].

DNA Methylation Biomarkers in Cancer Detection

Tissue-Based Methylation Biomarkers

Tumor tissue remains a valuable source for DNA methylation biomarker discovery and validation. Studies utilizing reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) of breast cancer cohorts have revealed that methylation patterns in tumors follow global trends, including replication-linked hypomethylation and epigenomic instability characterized by either methylation gain (MG) or loss (ML) at CpG islands [6]. These patterns correlate with tumor grade, stage, TP53 mutations, and clinical outcomes [6]. After accounting for these global trends, researchers have identified hundreds of promoters and thousands of distal regulatory elements exhibiting cis-specific methylation-expression correlations, including established tumor suppressors and oncogenes [6].

Comprehensive methylation profiling of 1538 breast tumors identified six global trends affecting DNA methylation profiles: immune and stromal cell contamination, replication-linked hypomethylation clock, X-chromosome dosage compensation, and two processes of epigenomic instability at CpG islands [6]. This layered modeling approach demonstrates how global epigenetic instability can erode cancer methylomes and expose them to localized methylation aberrations that drive transcriptional changes in tumors [6].

Liquid Biopsy Approaches and Circulating DNA

Liquid biopsies—particularly analyses of cfDNA and circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in blood—offer a minimally invasive alternative to tissue biopsies for cancer detection and monitoring [5] [4]. Tumor-derived material shed into various body fluids provides a reservoir of cancer-specific biomarkers that reflect the entire tumor burden and molecular heterogeneity [5]. DNA methylation biomarkers are especially advantageous in liquid biopsy applications due to the inherent stability of DNA methylation patterns, their cancer-specific nature, and the relative enrichment of methylated DNA fragments in cfDNA due to nuclease protection [5].

Different bodily fluids offer varying advantages depending on cancer type. For urological cancers like bladder cancer, urine demonstrates superior sensitivity compared to blood (87% vs 7% for TERT mutations) due to direct contact with tumors [5]. Similarly, bile outperforms plasma for biliary tract cancers, stool for colorectal cancer, and cerebrospinal fluid for brain tumors [5]. This principle of "local" liquid biopsy sources often provides higher biomarker concentration and reduced background noise compared to systemic blood collection [5].

Table 2: Clinically Implemented DNA Methylation Biomarker Tests

| Test Name | Cancer Type | Biosample | Biomarker(s) | Regulatory Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epi proColon | Colorectal | Blood/Plasma | SEPT9 methylation | FDA-approved [4] [2] |

| Cologuard | Colorectal | Stool | Multiple methylation markers | FDA-approved [7] |

| Bladder EpiCheck | Bladder | Urine | 15 methylation markers | CE-IVD marked [4] |

| AssureMDx | Bladder | Urine | TWIST1, ONECUT2, OTX1 methylation | Commercially available [4] |

| Galleri | Multi-cancer | Blood | Genome-wide methylation patterns | FDA Breakthrough Device [5] |

| Shield | Colorectal | Blood | Methylation markers | FDA-approved [5] |

The translation of methylation biomarkers into clinical practice demonstrates their utility across the cancer care continuum, from early detection and diagnosis to prognosis and treatment monitoring. However, despite the identification of thousands of potential methylation biomarkers in research settings, only a limited number have achieved regulatory approval and routine clinical implementation [4]. This disparity highlights the significant challenges in biomarker validation and clinical translation.

Experimental Workflows in Methylation Biomarker Development

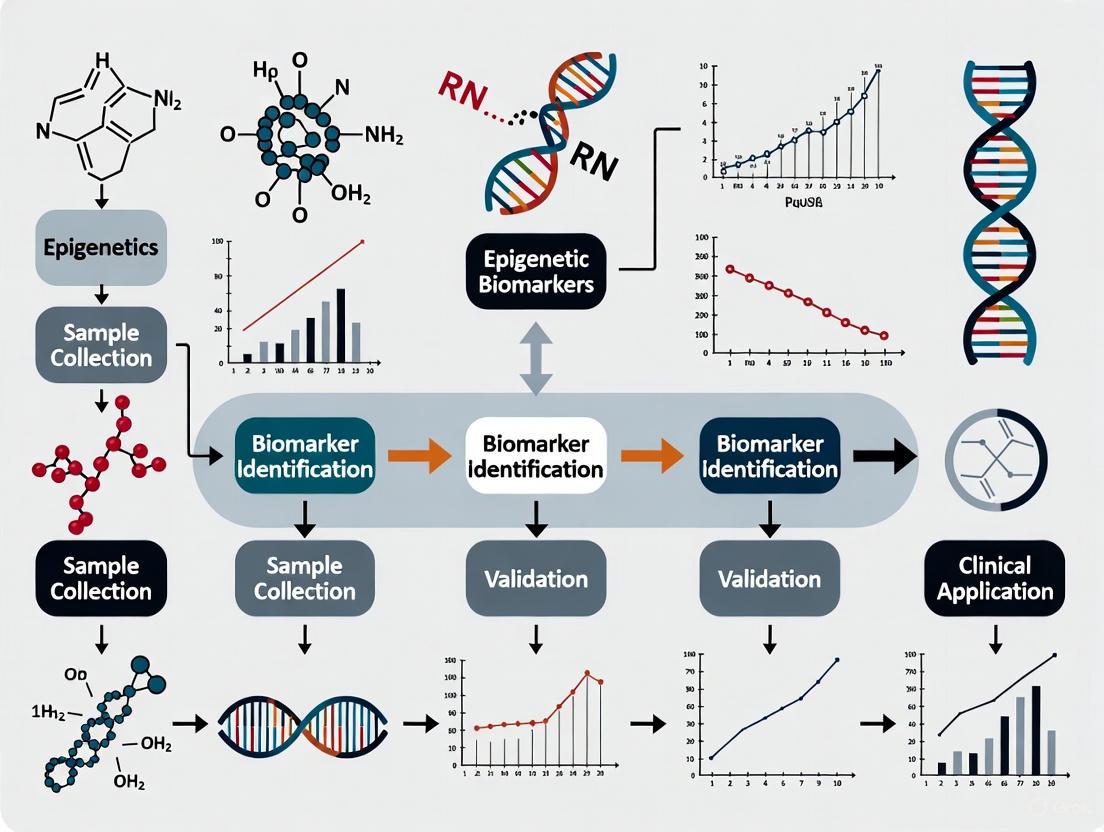

Biomarker Discovery and Validation Pipeline

The development of DNA methylation biomarkers follows a structured pipeline from discovery through clinical validation. Discovery phases typically utilize genome-wide approaches like WGBS or RRBS on tissue samples to identify differentially methylated regions between tumor and normal samples [5] [6]. Subsequent validation employs targeted methods such as qMSP or pyrosequencing in larger patient cohorts and liquid biopsy samples [5] [7]. This stepwise approach ensures that only the most promising biomarkers advance to costly clinical validation studies.

The Methylayer computational framework exemplifies a sophisticated approach to analyzing complex tumor methylation data [6]. This semi-supervised strategy integrates gene expression, genetic, and clinical information to computationally account for confounders like tumor microenvironment effects before inferring global methylation trends and identifying candidate loci for epigenetic cis-regulation [6]. Such integrative approaches are essential for distinguishing driver epigenetic events from passenger alterations in cancer.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for DNA Methylation Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits | EZ DNA Methylation kits, MethylEdge | Chemical conversion of unmethylated cytosines to uracils while preserving methylated cytosines [5] |

| DNA Methyltransferases | DNMT1, DNMT3A, DNMT3B | Enzymatic methylation establishment and maintenance; targets for epidrug development [3] [1] |

| Methyl-Sensitive Restriction Enzymes | HpaII, NotI, SmaI | Detection of methylation status at specific recognition sites [2] |

| Methylated DNA Immunoprecipitation Reagents | MeDIP kits, Methylated DNA Capture kits | Enrichment of methylated DNA fragments using 5mC-specific antibodies [5] |

| PCR Reagents for Methylation Analysis | Methylation-specific PCR primers, HotStart Taq polymerases | Amplification and detection of methylation patterns at specific loci [5] [7] |

| Whole Genome Amplification Kits | REPLI-g, GenomePlex | Amplification of limited DNA samples while preserving methylation patterns [7] |

| DNA Integrity Assessment Kits | Genomic DNA Quality Assessment, DV200 metrics | Quality control for fragmented DNA from FFPE or liquid biopsy samples [7] |

| Methylation Standards | Fully methylated and unmethylated control DNA | Quantification standards and assay controls [7] [2] |

Clinical Translation and Future Perspectives

Challenges in Biomarker Translation

Despite the identification of numerous promising DNA methylation biomarkers, their translation into clinical practice faces several significant challenges. The pre-analytical factors including sample collection, processing, and storage conditions can significantly impact methylation measurements, particularly in liquid biopsies where ctDNA concentrations are low [5] [7]. Analytical validation requires demonstrating robust performance across multiple sites and populations, while clinical utility must be established through large-scale prospective studies showing improved patient outcomes [5] [4].

Additional barriers include the need for standardized protocols, demonstration of cost-effectiveness, and navigation of regulatory pathways [4]. Even successfully translated tests like the SEPT9 methylation assay for colorectal cancer screening face limitations; while it shows good sensitivity for cancer detection (pooled sensitivity 0.71), its performance for detecting precancerous lesions is suboptimal, leading to recommendations against its use in some screening guidelines [2]. These challenges underscore the considerable gap between biomarker discovery and clinical implementation.

Emerging Applications and Future Directions

Future applications of DNA methylation biomarkers extend beyond cancer detection to include prognosis, therapy selection, and disease monitoring. Multi-cancer early detection tests (MCEDs), such as Galleri, which leverage genome-wide methylation patterns in cfDNA, represent a promising approach for population-level cancer screening [5]. The stability of cancer-specific methylation patterns and their enrichment in cfDNA make them particularly suitable for detecting minimal residual disease and early recurrence [5] [4].

The integration of machine learning approaches with DNA methylation data enables the development of sophisticated prediction models. Recent research demonstrates that machine learning algorithms can effectively analyze DNA methylation arrays and epigenetic biomarker datasets to build risk assessment models for cancer and other diseases [8]. These computational approaches can optimize risk prediction by combining clinical features with epigenetic biomarkers, potentially enabling early disease screening and personalized intervention [8].

The evolving landscape of DNA methylation research continues to provide insights into cancer biology while offering practical tools for clinical management. As technologies advance and our understanding of epigenetic mechanisms deepens, DNA methylation biomarkers are poised to play an increasingly prominent role in precision oncology, potentially enabling earlier detection, more accurate prognosis, and personalized therapeutic approaches for cancer patients.

The pursuit of early cancer detection has traditionally focused on genetic mutations—alterations in the DNA sequence of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes that drive carcinogenesis. While these mutational signatures provide crucial insights, they represent only one component of the molecular machinery driving cancer development. In recent years, epigenetic biomarkers have emerged as powerful alternatives and complements to traditional genetic markers, offering distinct advantages for early cancer detection, diagnosis, and prognosis [9].

Epigenetic modifications, defined as heritable changes in gene expression without alterations to the underlying DNA sequence, include DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNA expression. These modifications serve as critical regulatory mechanisms that can be influenced by environmental factors, lifestyle, and aging, potentially providing a more dynamic view of cancer risk and progression [10] [9]. This review systematically compares epigenetic and genetic biomarkers in the context of early cancer detection, highlighting the technical advantages, clinical validity, and practical benefits of epigenetic markers through current experimental data and methodological protocols.

Comparative Advantages of Epigenetic Biomarkers

Epigenetic biomarkers present several distinct technical and biological advantages over traditional genetic mutation-based approaches for early cancer detection, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Genetic versus Epigenetic Biomarkers for Early Cancer Detection

| Feature | Genetic Biomarkers | Epigenetic Biomarkers |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Basis | Changes in DNA sequence (mutations, translocations, deletions) [9] | Reversible modifications without DNA sequence change (methylation, histone mods) [9] |

| Frequency in Cancer | Varies by cancer type; often require specific mutations | Highly frequent and widespread; hyper/hypomethylation common early event [9] [11] |

| Tissue Specificity | Limited; often shared across cancer types | High; tissue-specific methylation patterns enable origin determination [12] |

| Dynamic Range | Static once mutated | Dynamic; reflects changing microenvironment and disease progression [10] [13] |

| Sample Compatibility | Requires sufficient tumor DNA | Compatible with fragmented DNA in blood; stable in circulation [12] [13] |

| Technical Detection | Requires high coverage to find rare variants | Amenable to amplification; sensitive detection of rare cell populations [12] |

| Influence Factors | Primarily inherited or random mutations | Modifiable by environment, lifestyle, and therapeutics [9] [14] |

The tissue-specific nature of epigenetic patterns provides a particular advantage for cancer detection. Unlike genetic mutations which may be similar across different cancers, DNA methylation patterns are highly tissue-specific, potentially allowing not just cancer detection but also identification of the tissue of origin [12]. Furthermore, epigenetic changes are often more frequent than genetic mutations in early carcinogenesis, with promoter hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes occurring commonly across cancer types [9] [11].

Experimental Validation: Methodologies and Data

DNA Methylation Biomarkers in Ovarian Cancer

A 2025 clinical validation study demonstrates the prognostic utility of DNA methylation biomarkers in relapsed ovarian cancer [13]. The researchers developed and validated PLAT-M8, an 8-CpG blood-based methylation signature linked to chemoresistance and overall survival.

Table 2: PLAT-M8 Methylation Signature Performance in Relapsed Ovarian Cancer

| Parameter | Class 1 Methylation | Class 2 Methylation |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Survival | Shorter survival (HR: 2.50, 95% CI: 1.64-3.79) [13] | Longer survival |

| Platinum Sensitivity | Platinum-resistant [13] | Platinum-sensitive [13] |

| Clinical Features | Older age (>75), advanced stage, residual disease [13] | Higher complete response rates (RECIST) [13] |

| Carboplatin Monotherapy | Poor prognosis (adj. HR: 9.69, 95% CI: 2.38-39.47) [13] | Better prognosis |

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Collection: Whole blood samples collected from patients at first relapse

- Cohorts: BriTROC-1 (n=47), OV04 (n=57), plus additional validation sets

- DNA Processing: Extracted DNA subjected to bisulfite conversion

- Methylation Analysis: Bisulfite pyrosequencing to quantify DNA methylation at 8 identified CpG sites

- Statistical Analysis: Consensus clustering to determine DNA methylation classes; Cox regression to assess overall survival concerning clinicopathological characteristics [13]

RNA Modification Analysis for Colorectal Cancer Detection

A novel approach for early colorectal cancer detection utilizes RNA modification patterns in blood samples through LIME-seq (low-input multiple methylation sequencing), published in Nature Biotechnology in 2025 [12].

Table 3: LIME-seq Performance in Colorectal Cancer Detection

| Metric | Performance |

|---|---|

| Sample Type | Blood plasma (liquid biopsy) |

| Target Analytes | tRNA methylation patterns, microbiome-derived signals |

| Study Population | 27 colon cancer patients vs. 36 healthy controls |

| Key Finding | Noticeable methylation changes in tRNA between cancer and control groups [12] |

| Advantage | Captures host microbiota activity reflecting tumor microenvironment [12] |

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Cell-free RNA isolated from blood plasma

- Library Preparation: LIME-seq uses HIV reverse transcriptase to create cDNA from cell-free RNA, with RNA-cDNA ligation strategy to capture short RNA species typically lost in commercial kits

- Sequencing: Simultaneous detection of RNA modifications at nucleotide resolution across multiple RNA species

- Analysis: Evaluation of tRNA-derived methylation signals and microbial genome-derived signals; comparison of methylation patterns between cancer patients and healthy controls [12]

The following diagram illustrates the LIME-seq experimental workflow:

Machine Learning Approaches for Epigenetic Biomarker Analysis

A 2025 study in Frontiers in Public Health utilized machine learning to analyze the relationship between 30 epigenetic biomarkers and cancer risk, demonstrating the power of computational approaches for epigenetic biomarker analysis [8].

Experimental Protocol:

- Data Source: NHANES database DNA methylation arrays and epigenetic biomarker datasets

- Algorithms: Nine machine learning algorithms tested (AdaBoost, GBM, KNN, LightGBM, MLP, RF, SVM, XGBoost, Logistic Regression)

- Validation: 5-fold cross-validation with grid search for parameter optimization

- Performance Metrics: Accuracy, MCC, Sensitivity, Specificity, AUC, F1 Score

- Feature Analysis: SHAP values to determine biomarker contribution to predictive models [8]

The study found that epigenetic age acceleration was strongly associated with cancer risk, with gender and smoking-related epigenetic biomarkers (PACKYRSMort) among the top contributing features [8].

Technical and Implementation Advantages

Enhanced Sensitivity in Liquid Biopsies

Epigenetic biomarkers offer practical advantages in liquid biopsy applications due to their chemical stability and abundance in circulation. Cell-free DNA methylation patterns remain stable in blood plasma, enabling detection of cancer-specific signals even at low concentrations [12] [13]. This addresses a key limitation of ctDNA mutation detection, which suffers from low concentration and high fragmentation in early-stage cancers [15].

The following diagram illustrates how epigenetic signals provide enhanced detection capabilities in liquid biopsies:

Dynamic Monitoring and Intervention Response

Unlike static genetic mutations, epigenetic marks are reversible and dynamic, allowing for monitoring of disease progression and treatment response. Studies have shown that epigenetic profiles change following therapeutic interventions, as demonstrated in studies of ketamine treatment for MDD and PTSD where reductions in epigenetic age were observed following treatment [14]. This dynamic nature provides opportunities for monitoring therapeutic efficacy and disease recurrence.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for Epigenetic Cancer Biomarker Investigation

| Tool Category | Specific Products/Platforms | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Methylation Arrays | Illumina Infinium HumanMethylationEPIC 850k BeadChip [14] [8] | Genome-wide methylation profiling at ~850,000 CpG sites |

| Bisulfite Conversion | EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research) [14] | Chemical conversion of unmethylated cytosines for methylation analysis |

| Data Analysis Tools | Minfi R package [14], ENmix [14] | Preprocessing, normalization, and analysis of methylation array data |

| Epigenetic Clocks | GrimAge, PhenoAge, OMICmAge, DunedinPACE [14] [8] | Assessment of biological age acceleration from methylation data |

| Single-Cell Epigenomics | Single-cell RNA-sequencing, single-nucleus RNA-sequencing [10] | Resolution of intra-tumor heterogeneity and cell-specific states |

| Machine Learning | Scikit-learn, XGBoost, SHAP analysis [8] | Predictive model development and biomarker contribution analysis |

Epigenetic biomarkers represent a transformative approach to early cancer detection, offering significant advantages over traditional genetic mutation-based markers. Their tissue specificity, frequency in early carcinogenesis, chemical stability in circulation, and dynamic nature provide powerful capabilities for detecting cancer at its most treatable stages. The experimental data and methodologies reviewed here demonstrate the robust clinical validity of epigenetic signatures across multiple cancer types, while highlighting the importance of standardized protocols and analytical frameworks. As the field advances, integration of multimodal epigenetic data with machine learning approaches will further enhance the sensitivity and specificity of epigenetic biomarkers, ultimately improving early cancer detection and patient outcomes.

The transformation of a normal cell into a cancerous one is driven not only by genetic mutations but also by profound epigenetic alterations. Among these, DNA methylation changes are fundamental, characterized by two seemingly paradoxical hallmarks: global genomic hypomethylation and locus-specific hypermethylation [16] [17]. These changes occur early in carcinogenesis and continue to evolve throughout tumor progression and metastasis [17]. Global hypomethylation, the first epigenetic abnormality identified in human tumors, primarily affects repetitive DNA sequences and can lead to genomic instability and oncogene activation [16] [2]. Conversely, locus-specific hypermethylation frequently targets CpG islands in promoter regions, resulting in the transcriptional silencing of critical tumor suppressor genes [18] [17]. This review will objectively compare the experimental frameworks used to validate epigenetic biomarkers born from these hallmarks, providing a guide for their application in early cancer detection.

Molecular Mechanisms and Functional Consequences

The Dual Phenomena of DNA Methylation in Cancer

The core methylation changes in cancer are orchestrated by the DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) family of enzymes. DNMT1 is primarily responsible for maintaining existing methylation patterns after DNA replication, while DNMT3A and DNMT3B perform de novo methylation, establishing new methylation patterns [2] [19]. In cancer, the dysregulation of these enzymes leads to a widespread disruption of the normal epigenome.

- Global Hypomethylation: This phenomenon is largely driven by a genome-wide loss of methylation, particularly in repetitive DNA sequences such as satellite DNAs, LINE-1 elements, and Alu repeats [16]. This loss of methylation can cause chromosomal instability, reactivation of transposable elements, and loss of genomic imprinting, all of which contribute to a cellular environment permissive for malignant transformation [16] [2]. For instance, hypomethylation of the juxtacentromeric satellite DNA has been significantly associated with tumor grade in ovarian carcinomas and serves as a marker for risk of relapse and overall survival [16].

- Locus-Specific Hypermethylation: In parallel, specific CpG islands that are normally unmethylated become hypermethylated. This aberrant methylation predominantly affects promoter regions of genes involved in critical cellular pathways, including tumor suppression, cell cycle regulation, DNA repair, and apoptosis [18] [17]. Well-documented examples include the hypermethylation of the MGMT promoter in gliomas, which predicts a better response to temozolomide therapy, and the silencing of MLH1 in a subset of colorectal cancers, leading to microsatellite instability [18].

Integrated Pathway of Epigenetic Dysregulation in Tumorigenesis

The following diagram synthesizes the core mechanisms and functional consequences of DNA methylation changes in cancer, illustrating how global hypomethylation and locus-specific hypermethylation collectively drive tumorigenesis.

Experimental Methodologies for Methylation Analysis

The validation of DNA methylation biomarkers relies on a diverse toolkit of laboratory techniques, each with specific strengths, resolutions, and applications. The choice of method depends on the experimental goal, required throughput, resolution, and the nature of the sample material (e.g., tissue, blood, urine) [20] [2].

Table 1: Comparison of Key DNA Methylation Detection Techniques

| Method Category | Specific Technique | Key Principle | Resolution | Throughput | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Analysis | Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) | Bisulfite conversion followed by whole-genome sequencing | Single-base | High | Discovery of novel methylation markers [20] [2] |

| Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS) | Bisulfite sequencing of CpG-rich regions selected by restriction enzyme digest | Single-base | Medium-High | Cost-effective methylation profiling [21] [2] | |

| Methylation Microarrays (e.g., EPIC) | Bisulfite-converted DNA hybridized to probe arrays | Single-CpG site | High | Large-scale epigenome-wide association studies (EWAS) [22] [23] | |

| Region-/Site-Specific Analysis | (Quantitative) Methylation-Specific PCR (qMSP) | PCR with primers specific for methylated vs. unmethylated sequences after bisulfite conversion | Locus-specific | Medium | Highly sensitive validation and clinical assays [18] [23] |

| Bisulfite Pyrosequencing | Bisulfite conversion followed by sequencing-by-synthesis | Single-base within a locus | Medium | Quantitative validation of CpG sites [18] [23] [2] | |

| Methylation-Sensitive High-Resolution Melting (MS-HRM) | Post-bisulfite PCR analysis based on DNA melting profile differences | Locus-specific | Medium | Screening and methylation level quantification [22] [23] | |

| Direct Methylation Analysis | Nanopore Sequencing | Direct detection of 5mC without bisulfite conversion as DNA passes through a protein nanopore | Single-base | High | Real-time analysis of long DNA fragments, avoids bisulfite bias [2] |

Advanced Workflow for Biomarker Validation in Liquid Biopsies

A significant challenge in clinical oncology is the non-invasive detection of cancer. Liquid biopsies, which analyze circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) from blood plasma, present a promising solution but are complicated by the low abundance of ctDNA. The following workflow outlines a sophisticated approach for validating methylation biomarkers in such challenging samples, incorporating a novel classification algorithm to enhance detection sensitivity.

This workflow highlights the EpiClass algorithm, a method developed to improve biomarker performance in liquid biopsies. Unlike approaches that rely on the average methylation level across a locus, EpiClass analyzes the distribution of methylation densities on individual DNA molecules (epialleles). Cancer-derived ctDNA often contains molecules with high methylation density, whereas background methylation from normal cells tends to be more heterogeneous and lower. EpiClass identifies optimal thresholds in these distributions to classify samples with higher sensitivity and specificity, even when the tumor DNA is highly diluted [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The successful development and validation of epigenetic biomarkers depend on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The table below details key solutions used in the featured experiments and the broader field.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Epigenetic Biomarker Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits (e.g., EZ DNA Methylation-Gold Kit) | Chemically converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils, while methylated cytosines remain unchanged. This is the foundational step for most methylation assays [22] [23]. | Essential for pre-processing DNA before qMSP, pyrosequencing, and sequencing-based methods [22]. |

| Methylation-Specific PCR (qMSP) Assays | Primer and probe sets designed to specifically amplify either the methylated or unmethylated version of a bisulfite-converted target sequence [23]. | Quantitative detection of hypermethylated biomarkers like MGMT or GSTP1 in clinical samples [18] [17]. |

| Control DNA (e.g., EpiTect Control DNA) | Pre-methylated and unmethylated DNA from human cell lines, used as standards for assay calibration and quality control [22]. | Included in MS-HRM and qMSP runs to create standard curves (e.g., 0%, 1%, 10%, 100% methylated) [22]. |

| Methylated DNA Immunoprecipitation (MeDIP) Kits | Uses an antibody against 5-methylcytosine to immunoprecipitate and enrich methylated DNA fragments from the genome [22]. | Enrichment for genome-wide methylation screening using microarrays or sequencing [22]. |

| Cell-free DNA (cfDNA) Extraction Kits | Specialized kits designed to isolate short-fragment, low-concentration cfDNA from blood plasma or other body fluids [21] [20]. | Preparation of template DNA for liquid biopsy-based methylation tests from patient plasma samples [21]. |

| Infinium Methylation BeadChips (e.g., EPIC array) | Microarray platforms that interrogate the methylation status of hundreds of thousands to over a million CpG sites across the genome [22] [23]. | Large-scale epigenome-wide association studies (EWAS) for biomarker discovery [22] [23]. |

Comparative Performance of Clinically Relevant Methylation Biomarkers

The ultimate test of an epigenetic biomarker is its performance in a clinical setting. The following table summarizes key validated biomarkers, their detection in various sample types, and their clinical utility for early detection and diagnosis.

Table 3: Performance and Application of DNA Methylation Biomarkers in Cancer

| Cancer Type | Key Methylation Biomarkers | Sample Type | Reported Performance | Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal Cancer (CRC) | SEPT9 [18] [2], SDC2 [20] | Blood (plasma), Stool [20] | Sensitivity: 71%, Specificity: 92% (for SEPT9 in a meta-analysis) [2] | Screening; blood-based SEPT9 test (Epi proColon) is FDA-approved [2]. |

| Glioblastoma | MGMT [18] | Tissue (FFPE) [18] | Predictive of response to temozolomide chemotherapy; combined with IDH1 status for prognosis [18]. | Predictive & Prognostic; standard of care testing [18]. |

| Lung Cancer | SHOX2, PTGER4 [20] [17] | Blood (plasma), Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid [20] | Able to discriminate between malignant and non-malignant lung disease in plasma [17]. | Diagnostic aid, particularly for indeterminate lung nodules [17]. |

| Prostate Cancer | GSTP1 [18] [23] | Tissue (FFPE), Urine [18] | Highly specific for prostate cancer detection in tissue [18]. | Diagnostic; helps distinguish cancer from benign prostate hyperplasia [18]. |

| Breast Cancer | Panel of 4 markers (e.g., TRDJ3, PLXNA4) [20] | Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) [20] | Sensitivity: 93.2%, Specificity: 90.4% (for a 4-marker panel) [20]. | Early detection; demonstrates potential of blood-based immune cell methylation signatures [20]. |

| Ovarian Cancer | ZNF154 [21] | Blood (plasma) [21] | Sensitivity: 91.7%, Specificity: 100% (using EpiClass algorithm in a validation cohort) [21]. | Early detection; outperformed CA-125 in detecting etiologically diverse tumors [21]. |

The dual hallmarks of tumorigenesis—global hypomethylation and locus-specific hypermethylation—provide a rich source of biomarkers for cancer detection. The experimental data and methodologies compared in this guide demonstrate that the successful translation of these biomarkers, particularly for early detection, hinges on several factors: the choice of analytical method (with bisulfite-based techniques being the current standard), the biological sample (where liquid biopsies are gaining prominence), and the data analysis strategy (where algorithms like EpiClass show promise in enhancing signal detection in noisy samples) [21] [20] [2].

Future development will likely focus on multi-marker panels to improve sensitivity across heterogeneous cancer types and stages. Furthermore, the integration of methylation signatures with other molecular data (genetic, proteomic) using machine learning models presents a powerful path forward for developing the next generation of diagnostic tools [20] [17]. While challenges remain in standardizing assays and validating markers in large prospective screening populations, the existing body of work firmly establishes DNA methylation as a cornerstone of cancer biology with immense, and increasingly realized, clinical potential.

Epigenetic biomarkers, dynamic and reversible modifications that regulate gene expression without altering the DNA sequence itself, have emerged as powerful instruments in oncology [24]. Their ability to provide early indicators of malignant transformation, track disease progression, and predict therapeutic response positions them at the forefront of cancer precision medicine [25]. Unlike genetic mutations, epigenetic alterations are potentially reversible, offering unique therapeutic opportunities [24]. The analysis of these markers in liquid biopsies—through the detection of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and other tumor-derived materials in blood or other biofluids—provides a minimally invasive window into the tumor's molecular landscape, enabling real-time monitoring and overcoming the limitations of traditional tissue biopsies [5] [25]. This guide provides a comparative evaluation of the three principal classes of epigenetic biomarkers—DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNAs—focusing on their mechanisms, detection technologies, and validated clinical applications in cancer early detection.

DNA Methylation Biomarkers

DNA methylation, the covalent addition of a methyl group to the 5-carbon position of cytosine in CpG dinucleotides, is the most extensively characterized epigenetic mark in cancer [5] [25]. In cancer cells, typical patterns include global hypomethylation, which can lead to genomic instability, and promoter-specific hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes, which silences their expression [5] [20]. These alterations often occur early in tumorigenesis and are highly stable, making them excellent biomarkers for early detection [5].

Key Methodologies and Workflows

A cornerstone technology for DNA methylation analysis is bisulfite sequencing. This method relies on the treatment of DNA with sodium bisulfite, which deaminates unmethylated cytosines to uracils, while methylated cytosines remain unchanged. Subsequent PCR amplification and sequencing allow for single-nucleotide resolution mapping of 5-methylcytosine (5mC) [24].

Figure 1: Bisulfite sequencing workflow for DNA methylation analysis.

The choice between untargeted and targeted approaches depends on the research goal. Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) provides comprehensive, base-resolution methylome coverage but is resource-intensive and requires high sequencing depth [24]. Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS) offers a cost-effective alternative by using restriction enzymes to enrich for CpG-rich regions like promoters and CpG islands, making it suitable for large-cohort studies [24]. For clinical validation and diagnostic applications, targeted methods such as methylation-specific PCR (qMSP) and digital PCR (dPCR) are preferred due to their high sensitivity, specificity, and suitability for analyzing low-abundance ctDNA in liquid biopsies [5] [20].

Performance Data and Clinical Applications

DNA methylation biomarkers have been validated across numerous cancer types. The table below summarizes selected biomarkers and their performance in early cancer detection.

Table 1: DNA Methylation Biomarkers in Early Cancer Detection

| Cancer Type | Methylation Biomarkers | Sample Type | Detection Method | Performance Notes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal Cancer | SDC2, SEPT9 |

Plasma, Feces | Real-time PCR | SEPT9 test FDA-approved; high sensitivity and specificity for early-stage detection. |

[20] |

| Breast Cancer | Panel of 15 markers | ctDNA | WGBS, Targeted BS-seq | AUC of 0.971 in validation cohort. | [20] |

| Lung Cancer | SHOX2, RASSF1A |

Plasma, Bronchoalveolar Lavage | Methylight, NGS | Effective detection in liquid biopsies. | [20] |

| Bladder Cancer | CFTR, SALL3 |

Urine | Pyrosequencing | High sensitivity (87%) reported for urine-based mutation detection. | [5] [20] |

| Esophageal Cancer | Panel of 12 markers | Tissue | Microarray | AUC of 96.6% in TCGA data validation. | [20] |

Liquid biopsy source selection is critical for optimizing detection. While blood plasma is universally applicable, local biofluids can offer higher biomarker concentrations. For example, urine outperforms plasma for bladder cancer detection, and bile is superior for biliary tract cancers [5]. The inherent stability of DNA and the relative enrichment of methylated DNA fragments in cfDNA further enhance their utility in liquid biopsy settings [5].

Histone Modification Biomarkers

Histone modifications are post-translational alterations—including acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination—to histone proteins that regulate chromatin structure and gene accessibility [26] [27]. These modifications are established, interpreted, and removed by "writer," "reader," and "eraser" enzymes, respectively [27]. Aberrant histone modification patterns are a hallmark of cancer and can drive uncontrolled proliferation and therapy resistance [26].

Key Methodologies and Workflows

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) is a widely used method for mapping histone modifications genome-wide. It involves cross-linking proteins to DNA, immunoprecipitating the protein-DNA complexes with antibodies specific to a histone mark, and then sequencing the bound DNA fragments [24].

Mass spectrometry (MS)-based proteomics provides an unbiased, quantitative profile of histone post-translational modifications. This approach has been successfully applied to clinical FFPE and frozen tissues, revealing distinct epigenetic signatures associated with cancer subtypes and patient prognosis [26].

Figure 2: ChIP-seq workflow for histone modification profiling.

Performance Data and Clinical Applications

Histone modifications can serve as powerful diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers. A landmark multi-omics study of over 200 breast tumors identified a specific histone modification signature that distinguishes aggressive triple-negative breast cancers (TNBCs) from other subtypes [26]. This signature was characterized by an increase in H3K4 methylation (H3K4me1/me2) and a decrease in marks such as H3K27me3 and H4K20me3 [26]. Furthermore, high levels of H3K4me2 were mechanistically proven to sustain the expression of genes driving the TNBC phenotype, and inhibiting H3K4 methyltransferases reduced tumor growth in vivo, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic target [26].

Table 2: Experimentally Validated Histone Modification Associations in Cancer

| Histone Mark | Cancer Type | Experimental Method | Biological & Clinical Association | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me2/me3 | Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC) | Mass Spectrometry, ChIP-seq, CRISPR-editing | Sustains expression of TNBC phenotype genes; associated with poor prognosis; inhibition reduces tumor growth. | [26] |

| H3K27me3 | Various Cancers | ChIP-seq, Immunohistochemistry | Polycomb-mediated gene silencing; target of EZH2 inhibitors. | [25] [27] |

| H4K16ac | Various Cancers | Mass Spectrometry | General hallmark of cancer; progressively decreases in breast cancer subtypes. | [26] |

| H4K20me3 | Various Cancers | Mass Spectrometry | Decreased in cancer; associated with genomic instability. | [26] |

The translation of histone modifications into clinical practice faces challenges, including tumor heterogeneity and the need for highly specific antibodies and complex data analysis [28]. However, their reversible nature makes them attractive therapeutic targets, with drugs like histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors already in clinical use [27] [28].

Non-Coding RNA Biomarkers

Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) are functional RNA molecules that do not code for proteins. They are crucial regulators of gene expression at the epigenetic, transcriptional, and post-transcriptional levels [29] [30]. Key ncRNA classes include microRNAs (miRNAs), long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), and circular RNAs (circRNAs), all of which are frequently dysregulated in cancer [31] [29].

Key Methodologies and Workflows

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) is the primary discovery tool for profiling ncRNA expression. It allows for the simultaneous detection and quantification of all ncRNA classes without prior knowledge of sequences [24] [31]. For validation and clinical application, quantitative PCR (qPCR) is the gold standard due to its high sensitivity, specificity, and throughput [31]. Computational tools and machine learning are increasingly used to identify ncRNA signatures from high-throughput sequencing data [31].

Figure 3: Workflow for ncRNA biomarker discovery and validation.

Performance Data and Clinical Applications

ncRNAs are stable in biofluids and exhibit tissue- and cancer-specific expression patterns, making them excellent non-invasive biomarkers [31] [30]. Panels of ncRNAs often demonstrate high diagnostic accuracy.

Table 3: Validated Non-Coding RNA Biomarkers in Gastrointestinal and Breast Cancers

| ncRNA Class | Example Biomarkers | Cancer Type | Function & Clinical Utility | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miRNA | miR-21, miR-92a |

Gastrointestinal, Breast | Oncogenic; promotes proliferation; diagnostic accuracy and poor prognosis. | [31] [30] |

| lncRNA | H19, MALAT1, HOTAIR |

Gastrointestinal, Breast, HNSCC | Regulates chromatin state, transcription; associated with metastasis and therapy resistance. | [31] [29] |

| circRNA | Various (e.g., circCCDC66) |

Various | Sponges miRNAs; regulates cytokine signaling and immune evasion in cancer. | [29] |

In gastrointestinal cancers, a panel including the lncRNAs H19, NEAT1, and MALAT1 and the miRNAs miR-21 and miR-92a has been consistently validated with excellent diagnostic accuracy and association with poor overall survival [31]. In breast cancer, ncRNA expression profiles differ significantly across molecular subtypes, offering potential for subtype classification and predicting response to therapy [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The experimental protocols described rely on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details key solutions required for research in this field.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Epigenetic Biomarker Studies

| Reagent / Solution | Primary Function | Key Considerations for Use |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Bisulfite | Chemical conversion of unmethylated cytosine to uracil for DNA methylation analysis. | Optimized kits are essential to minimize DNA degradation and ensure complete conversion. |

| Methylation-Specific Antibodies | Immunoprecipitation of methylated DNA (MeDIP) or modified histones (ChIP). | Specificity and lot-to-lot consistency are critical for reproducibility in ChIP-seq and MeDIP-seq. |

| Histone Modification-Specific Antibodies | Detection and enrichment of specific histone PTMs (e.g., H3K4me3, H3K27ac) in ChIP assays. | Rigorous validation using known positive and negative controls is required for reliable results. |

| CRISPR/dCas9 Epigenetic Editors | Targeted alteration of epigenetic marks (e.g., dCas9-DNMT3A for methylation) for functional validation. | Used to establish causality between a specific epigenetic mark and gene expression or phenotype. |

| Cell-Free DNA Blood Collection Tubes | Stabilization of cfDNA in blood samples for liquid biopsy analysis. | Prevents genomic DNA contamination and degradation of cfDNA, which is critical for accurate quantification. |

| RNA Stabilization Reagents | Preservation of RNA integrity in liquid biopsies (e.g., plasma, urine) and tissues. | Prevents degradation of labile ncRNA molecules by RNases, ensuring accurate expression profiling. |

The three classes of epigenetic biomarkers offer complementary strengths. DNA methylation is the most technologically mature for clinical translation, with several FDA-approved or designated tests (e.g., Epi proColon, Shield) for cancer detection in liquid biopsies [5] [20]. Its stability and early emergence in tumorigenesis are key advantages. Histone modifications provide deep functional insights into the chromatin state of tumors and are promising therapeutic targets, though their clinical implementation is more complex due to technical challenges [26] [28]. Non-coding RNAs offer high sensitivity for detecting specific cancer types and subtypes from biofluids and are valuable for prognosis, but their regulatory networks are complex and require sophisticated computational analysis [31] [29] [30].

The future of epigenetic biomarkers lies in multi-omics integration. Combining data from DNA methylation, histone modifications, ncRNA profiling, and genetic alterations using artificial intelligence and machine learning will enable the identification of robust, multi-modal biomarker signatures [24] [27]. This integrated approach, particularly when applied to liquid biopsies, holds the greatest potential for achieving the ultimate goal of precision oncology: early, accurate, and dynamic detection of cancer to guide personalized therapeutic interventions.

Epigenetic marks, particularly DNA methylation and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), have emerged as powerful biomarkers in clinical cancer research. Their unique biochemical properties and stability in various sample types provide significant technical advantages for early detection, monitoring, and precision oncology. This guide objectively compares the performance of these epigenetic marks against traditional biomarkers and details the experimental methodologies harnessing their potential for clinical application.

Technical Advantages of Epigenetic Marks

Epigenetic modifications offer distinct stability and detectability profiles that make them superior to genetic alterations for many clinical applications.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Biomarker Stability and Detectability in Clinical Samples

| Biomarker Type | Stability in Clinical Samples | Primary Detection Methods | Key Technical Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Methylation (5mC) | High stability in FFPE tissues, plasma, and cfDNA; withstands bisulfite conversion [32] [33] [34] | Bisulfite sequencing (RRBS, WGBS), MSP, pyrosequencing, microarrays [32] [35] | Cost-effective amplification; high sensitivity/specificity in FDA-approved tests; tissue- and cancer-type specific patterns [32] [35] | Bisulfite conversion can degrade DNA; requires specific adjustment for cell-type heterogeneity in EWAS [32] |

| 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) | Stable epigenomic mark; patterns established early in tumorigenesis and persist through progression [36] | 5hmC-enriched sequencing, hMeDIP-Seq [37] [36] | Associated with active gene regulation; enables high-accuracy tissue of origin prediction (85.2%) [36] | Requires specialized enrichment protocols; less established in clinical workflows [36] |

| Histone Modifications | Moderate; requires specific preservation for ChIP assays [37] | ChIP-Sequencing, ChIP-String [37] | Defines functional chromatin states; reveals combinatorial patterns [37] | Technically challenging for low-input samples; not yet feasible for liquid biopsy [37] |

| Genetic Mutations | Stable in ctDNA but often at very low frequency in early stages [35] [34] | Targeted NGS, ddPCR [35] [34] | Straightforward interpretation; well-established in clinical pipelines [35] | Can lack sensitivity for early-stage cancer detection due to low variant allele frequency [35] |

Experimental Protocols for Epigenetic Analysis

Robust and sensitive methodologies are critical for leveraging epigenetic marks in clinical samples. The following workflows are foundational to the field.

Cell-Free DNA Methylation Analysis for Early Cancer Detection

This protocol is designed for genome-scale methylation analysis of low-input cfDNA from blood plasma, enabling early cancer detection and tissue-of-origin identification [33].

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Steps:

- Sample Collection & Processing: Collect whole blood (2×10 mL) in cell-free DNA BCT Streck tubes. Maintain at 15–25°C and process within 72 hours. Centrifuge at 1,600 × g for 10 minutes, transfer plasma, and perform a second centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 10 minutes. Aliquot and store plasma at -80°C [36].

- cfDNA Isolation: Extract cfDNA from plasma, normalizing to a low input of 5-10 ng for library construction [33].

- Library Preparation & Bisulfite Conversion: Use cell-free Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (cfRRBS). This method is optimized for minimal input and generates an average of three million high-quality CpGs per sample. Treat DNA with sodium bisulfite, converting unmethylated cytosines to uracils while methylated cytosines remain unchanged [32] [33].

- Sequencing & Data Analysis: Perform high-throughput sequencing (e.g., Illumina platforms). Align sequences to a reference genome (e.g., GRCh38) using tools like BWA-MEM2. Analyze data through a bioinformatics pipeline for differential methylation and deep-learning-powered tissue deconvolution models to correlate findings with clinical data [33] [36].

Targeted Methylation Sequencing for Multi-Cancer Early Detection

This approach uses custom probe panels to enrich for specific cancer-related methylation regions, optimizing for high sensitivity and specificity in detecting multiple cancer types from a single blood sample [35] [38].

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Steps:

- Probe Design & Panel Construction: Synthesize a custom panel of capture probes targeting >100,000 distinct regions encompassing over a million methylation sites. This panel is designed to differentiate cancer-specific methylation patterns [38].

- Pre-Capture Bisulfite Conversion: Isolate cfDNA and treat with sodium bisulfite. This "pre-capture" method is preferred for low-abundance cfDNA as subsequent PCR amplification increases library complexity before hybridization, reducing input requirements [38].

- Target Enrichment & Sequencing: Hybridize the bisulfite-converted and amplified library with the custom probe panel. Wash off non-specifically bound fragments and sequence the captured targets on a high-throughput platform [38].

- Bioinformatic Analysis & Machine Learning: Use machine learning (ML) algorithms, such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) or gradient boosting machines (GBMs), to analyze the sequenced methylation patterns. These models are trained to classify cancer status and predict the tissue of origin (TOO) with high accuracy [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of epigenetic clinical tests relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Epigenetic Analysis

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Bisulfite | Chemically converts unmethylated cytosine to uracil, allowing for methylation status determination via sequencing or PCR [32] [34] | Foundational step in MSP, bisulfite pyrosequencing, RRBS, and WGBS [32] |

| Twist Targeted Methylation Panel | Large pool of biotinylated oligonucleotide probes designed to capture and enrich specific methylation regions of interest from a sequencing library [38] | Used in MCED tests (e.g., GRAIL's Galleri) to enrich for 100,000+ regions from plasma cfDNA [35] [38] |

| Anti-5hmC Antibody | Specifically binds to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine for immunoprecipitation-based (hMeDIP) enrichment of 5hmC-modified DNA fragments [37] [36] | Enabling 5hmC profiling in tumor tissues and cfDNA; used to identify stable cancer-specific 5hmC signatures [36] |

| DNA Methyltransferases (DNMTs) / HDAC Inhibitors | Small molecule inhibitors (e.g., DNMT inhibitors Azacitidine) that reverse aberrant epigenetic marks, used as epidrugs [34] [39] | Therapeutic application; also used in vitro to test functional role of observed epigenetic changes [37] |

| Illumina Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip | Microarray-based technology for profiling methylation status at >850,000 CpG sites across the genome [40] | Used in large-scale epigenome-wide association studies (EWAS) for biomarker discovery [32] [40] |

The intrinsic stability of epigenetic marks in diverse clinical samples, coupled with advanced detection methodologies, positions them as indispensable tools for modern cancer research and diagnostic development. DNA methylation and 5hmC offer a powerful combination for sensitive early detection and accurate tissue-of-origin localization, directly addressing the challenges of cancer heterogeneity and low analyte abundance. As the field progresses, the integration of these epigenetic biomarkers with machine learning and multi-omics approaches will continue to refine their clinical utility, paving the way for more effective, personalized cancer management strategies.

Advanced Methodologies for Epigenetic Biomarker Analysis and Application

DNA methylation is a fundamental epigenetic mechanism involving the addition of a methyl group to the 5-carbon position of cytosine, primarily at cytosine-phosphate-guanine (CpG) dinucleotides, forming 5-methylcytosine (5mC) [41] [20]. This modification regulates gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence and plays pivotal roles in genomic imprinting, X-chromosome inactivation, and cellular differentiation [41] [5]. In cancer, aberrant DNA methylation patterns emerge early in tumorigenesis and remain stable throughout tumor evolution, making them ideal biomarkers for early detection [20] [5]. These alterations typically manifest as genome-wide hypomethylation accompanied by hypermethylation of specific CpG-rich gene promoters, particularly those of tumor suppressor genes [5].

The transition from microarray-based technologies to next-generation sequencing (NGS) platforms has revolutionized DNA methylation profiling, providing unprecedented resolution and coverage for biomarker discovery [41] [42]. While microarrays offer a cost-effective solution for profiling predefined CpG sites, NGS methods enable comprehensive mapping of methylation patterns across the entire genome, including previously unexplored regions [41] [43]. This comparison guide objectively examines the performance characteristics, experimental requirements, and applications of current DNA methylation profiling technologies within the context of validating epigenetic biomarkers for early cancer detection.

Technology Landscape: A Comparative Analysis of Profiling Methods

Microarray-Based Approaches

Principle: DNA methylation arrays integrate bisulfite conversion with hybridization to oligonucleotide probes fixed on a chip, allowing detection at specific CpG sites [44] [45]. The Illumina Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip represents the current state-of-the-art, with the EPICv2 version covering over 935,000 CpG sites [44].

Performance Characteristics: EPIC arrays demonstrate high reproducibility between technical replicates and strong concordance with whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) data [44]. However, they are limited to predefined CpG sites and favor CpG-rich regions like islands and promoters, potentially missing biologically significant methylation events in other genomic contexts [45].

Next-Generation Sequencing Approaches

Bisulfite Sequencing Methods: Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) represents the gold standard for base-resolution methylation profiling, providing comprehensive coverage of nearly every CpG site [43] [45]. Reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) offers a more targeted approach, using restriction enzymes to focus on CpG-rich regions at a lower cost [45]. However, bisulfite treatment causes substantial DNA degradation and introduces sequencing biases due to reduced sequence complexity [43] [45].

Enzymatic Conversion Methods: Enzymatic methyl-sequencing (EM-seq) utilizes enzymatic conversion rather than harsh chemical treatment, better preserving DNA integrity while maintaining base resolution [43] [45]. Studies show EM-seq has high concordance with WGBS while causing less DNA damage, making it particularly suitable for low-input samples and formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues [43].

Third-Generation Sequencing: Long-read technologies from Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) and PacBio enable direct detection of DNA methylation on native DNA without conversion [43] [45]. These platforms excel at resolving methylation patterns in repetitive regions and enable phasing of methylation haplotypes, but traditionally require more DNA input and have higher error rates than short-read sequencing [45].

Affinity Enrichment Methods: Techniques like methylated DNA immunoprecipitation sequencing (MeDIP-seq) use antibodies or methyl-binding proteins to enrich methylated DNA fragments before sequencing [41] [45]. While cost-effective for genome-wide methylation trends, they provide lower resolution and are biased toward highly methylated regions [41] [45].

Table 1: Comparative Performance of DNA Methylation Profiling Technologies

| Technology | Resolution | CpGs Covered | DNA Input | Cost | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPIC Array | Single CpG | ~935,000 sites | Moderate | $ | Large cohort studies [44] [45] |

| WGBS | Single-base | >28 million CpGs | High | $$$$ | Comprehensive methylome [41] [43] |

| RRBS | Single-base | ~2 million CpGs | Low | $$ | CpG island-focused studies [45] |

| EM-seq | Single-base | Comparable to WGBS | Low | $$$ | Low-input/degraded samples [43] [45] |

| ONT | Single-base | Genome-wide | High | $$$ | Repetitive regions, haplotype phasing [43] [45] |

| MeDIP-seq | ~150 bp | ~23 million CpGs | Moderate | $ | Genome-wide methylation trends [41] [45] |

Table 2: Technical Comparison Across Profiling Platforms

| Parameter | EPIC Array | WGBS | EM-seq | ONT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Degradation | Minimal | Substantial | Minimal | None |

| Base Resolution | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Throughput | High | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| FFPE Compatibility | Good | Limited | Good | Limited |

| 5hmC Discrimination | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Multiplexing Capacity | High | Medium | Medium | Low |

Analytical Performance in Cancer Research Context

Recent comparative studies evaluating DNA methylation detection approaches across human genome samples derived from tissue, cell lines, and whole blood provide critical performance data for technology selection [43]. EM-seq showed the highest concordance with WGBS, indicating strong reliability due to their similar sequencing chemistry [43]. While each method identified unique CpG sites, emphasizing their complementary nature, ONT sequencing captured certain loci uniquely and enabled methylation detection in challenging genomic regions that are difficult to assess with short-read technologies [43].

For cancer biomarker discovery, methylation arrays have demonstrated particular utility in developing classification models. A 2024 study comparing machine learning models for central nervous system tumor classification found that models trained on EPIC array data achieved accuracies above 95% in classifying tumor types, with neural network models maintaining performance until tumor purity fell below 50% [46]. This robustness to variable tumor purity is particularly valuable for clinical applications where sample quality may be compromised.

Experimental Protocols for Biomarker Validation

Discovery Phase Workflow

The initial discovery phase typically employs genome-wide approaches to identify differentially methylated regions (DMRs) associated with cancer states. A typical workflow involves:

Sample Preparation: Extract high-quality DNA from tumor tissues, blood, or other liquid biopsy sources. The recommended input for WGBS is 100ng-1μg, while EM-seq can work with lower inputs (10-100ng) [43] [45].

Library Preparation: For bisulfite-based methods, fragment DNA followed by bisulfite conversion using kits such as EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research). For enzymatic methods, use EM-seq kits that employ TET2 and APOBEC enzymes for gentler conversion [43] [45].

Sequencing: Sequence on appropriate platforms - Illumina short-read sequencers for WGBS/RRBS/EM-seq, or Nanopore/PacBio instruments for long-read approaches. Recommended coverage is 20-30x for WGBS [45].

Bioinformatic Analysis: Process data using specialized tools - BISMARK [46] or BSMAP [47] for alignment, and tools like DMRcate for identifying differentially methylated regions [44].

Validation of Methylation Biomarkers

Following discovery, potential biomarkers require rigorous validation using targeted methods:

Targeted Bisulfite Sequencing (Target-BS): This approach enables high-precision validation of specific gene regions' DNA methylation status through ultra-high depth sequencing (several hundred to thousands of times coverage) [47]. Specific gene regions of less than 300 base pairs are selected, and primers specific for bisulfite-treated DNA are designed for amplification [47].

Methylation-Specific PCR Methods: Quantitative methylation-specific PCR (qMSP) and digital PCR (dPCR) offer highly sensitive, locus-specific analysis suitable for clinical validation [5]. These methods are particularly useful for liquid biopsy applications where target abundance is low [20] [5].

Functional Validation: For established biomarkers, functional validation through CRISPR-Cas9 targeted editing experiments can demonstrate causality. The CRISPR-dCas9 system can introduce or remove methylation modifications at specific DNA sequences by fusing dCas9 with methyltransferases (e.g., DNMT3A) or demethylases (e.g., TET1) [47]. Subsequent assessment of gene expression changes via RT-qPCR and Western blotting confirms the functional impact of methylation changes [47].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for DNA Methylation Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Bisulfite | Converts unmethylated cytosine to uracil | WGBS, RRBS, Targeted BS [47] [45] |

| EM-seq Kit | Enzymatic conversion of unmethylated cytosines | Gentle conversion preserving DNA integrity [43] [45] |

| EPIC BeadChip Array | Genome-wide methylation profiling at predefined sites | Large cohort studies, clinical classification [44] [46] |

| 5mC Antibodies | Immunoprecipitation of methylated DNA | MeDIP-seq, immunofluorescence [41] [47] |

| DNA Methyltransferase Inhibitors | Global methylation interference | Functional studies (e.g., 5-azacytidine) [47] |

| CRISPR-dCas9 Methylation Editors | Targeted methylation/demethylation | Functional validation of specific loci [47] |

The evolving landscape of DNA methylation profiling technologies offers researchers multiple pathways for cancer biomarker discovery and validation. Microarrays provide cost-effective solutions for large-scale screening studies, while NGS methods deliver comprehensive methylome mapping at base resolution. The emergence of enzymatic conversion methods and long-read sequencing addresses limitations of traditional bisulfite-based approaches, particularly for challenging sample types.

For research focused on validating epigenetic biomarkers for early cancer detection, a strategic approach combining discovery and validation technologies shows greatest promise. Genome-wide discovery using EPIC arrays or WGBS/EM-seq followed by targeted validation with highly sensitive methods like Target-BS or dPCR creates a robust framework for biomarker development. As the field advances, integration of machine learning approaches for analyzing methylation data will further enhance classification accuracy and clinical utility, ultimately improving early cancer detection capabilities.

Liquid biopsy represents a transformative, minimally invasive approach in oncology that enables the detection and analysis of tumor-derived material in body fluids [48] [49]. Unlike traditional tissue biopsies, which provide a limited snapshot of a single tumor region, liquid biopsies capture the entire tumor burden and reflect the molecular heterogeneity of cancer [5]. The concept is grounded in the knowledge that blood and other bodily secretions contain tumor cells, nucleic acids, cellular components, and metabolites [48]. Among the various analytes, circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA)—small fragments of DNA released by tumor cells into the bloodstream—has demonstrated particular clinical promise due to advancements in DNA analysis technologies [48] [49].

ctDNA carries tumor-specific characteristics, such as somatic mutations, methylation changes, and fragmentation patterns, which distinguish it from normal cell-free DNA (cfDNA) that originates from the physiological apoptosis of healthy cells [48] [49]. The half-life of ctDNA is short, estimated between 16 minutes and several hours, allowing it to provide a real-time snapshot of tumor burden and enabling dynamic monitoring of disease progression and treatment response [50] [49]. The analysis of ctDNA and its features has created new avenues for cancer diagnosis, early detection, prognosis prediction, and monitoring of treatment response across a wide spectrum of malignancies [48] [51] [49].

Analytical Methodologies for ctDNA Analysis

The detection of ctDNA requires highly sensitive techniques due to its low abundance in circulation, especially in early-stage cancers or low-shedding tumors [48] [49]. The analytical methods can be broadly categorized into those targeting genomic alterations and those exploiting epigenetic or fragmentomic features.

Mutation-Based Detection Methods

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based methods, including digital droplet PCR (ddPCR) and BEAMing (beads, emulsion, amplification, magnetics), are targeted approaches ideal for detecting single or a few well-characterized mutations with high sensitivity and rapid turnaround times [48] [49]. They are particularly useful for monitoring known driver mutations in specific cancers, such as BRAF in melanoma, KRAS in lung and colorectal cancer, and ESR1 in breast cancer [48] [49].

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) methodologies enable a broader profiling of genomic alterations and include whole-exome sequencing (WES), whole-genome sequencing (WGS), and targeted approaches such as CAPP-Seq and TEC-Seq [48] [49]. These methods facilitate comprehensive assessment of numerous patient-specific genomic changes, providing a more detailed understanding of the disease, particularly in heterogeneous cancers with high genomic instability [49]. To overcome errors introduced during sequencing, methods incorporating unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) have been developed, such as Duplex Sequencing and the more recent CODEC method, which achieves 1000-fold higher accuracy than conventional NGS [49].

Epigenetic and Fragmentomic Approaches

Epigenetic modifications, particularly DNA methylation, have emerged as highly promising biomarkers for liquid biopsy [5]. DNA methylation involves the addition of a methyl group to cytosine bases at CpG dinucleotides and plays a crucial role in gene regulation [5]. In cancer, DNA methylation patterns are frequently altered, with tumors typically displaying both genome-wide hypomethylation and site-specific hypermethylation of CpG-rich gene promoters [5]. These alterations often occur early in tumorigenesis and remain stable throughout tumor evolution, making them ideal biomarkers [5].

Fragmentomics is another emerging field that analyzes the fragmentation patterns of cfDNA, including fragment sizes, end motifs, and nucleosome positioning [48] [52]. Cancer patients exhibit more diverse fragmentation patterns compared to healthy individuals, which can be leveraged to distinguish cancer-derived cfDNA [48]. The DELFI method, for example, uses a machine learning model incorporating genome-wide fragmentation profiles to detect cancer with high sensitivity [48].

Table 1: Comparison of Major ctDNA Analysis Technologies

| Method Category | Specific Technologies | Key Features | Best Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCR-Based | ddPCR, BEAMing | High sensitivity for known mutations, rapid turnaround, quantitative | Monitoring known mutations (e.g., EGFR, KRAS), tumor-informed MRD | Limited to a small number of predefined mutations |

| Next-Generation Sequencing | WES, WGS, CAPP-Seq, TEC-Seq | Broad genomic coverage, discovery of novel alterations, tumor-uninformed approaches possible | Comprehensive genomic profiling, identifying resistance mutations | Higher cost, longer turnaround, potential for sequencing artifacts |

| Methylation Analysis | Bisulfite sequencing (WGBS, RRBS), Microarrays, EM-seq | Stable, early cancer markers, tissue-of-origin identification | Early cancer detection, multi-cancer screening | Bisulfite conversion degrades DNA; requires sensitive detection |

| Fragmentomics | DELFI, NF profiling, end motif analysis | Does not require genetic alterations, provides insight into gene regulation | Early detection, differentiating cancer from benign conditions | Novel field, requires advanced bioinformatics |

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Protocol for Methylation-Based Detection in Breast Cancer

A 2025 study detailed a protocol for discovering and validating cfDNA methylation markers for breast cancer diagnosis and prognosis [53]. The workflow is summarized in the diagram below:

Sample Collection and Processing: The study utilized plasma samples from 201 breast cancer patients, 83 healthy donors, and 71 individuals with benign tumors [53]. Cell-free DNA was extracted from plasma following standard protocols, with quality control measures to ensure DNA integrity [53].

Marker Discovery and Assay Development: BC-specific methylation markers were identified using large-scale methylation datasets (850K and 450K arrays) [53]. The researchers identified 21 BC-specific methylated CpG sites that distinguished breast cancer from tumor-adjacent tissues with high diagnostic accuracy [53]. Multiplex digital droplet PCR (mddPCR) assays were developed to detect methylation at eight key markers in the cfDNA [53].

Validation and Functional Analysis: The diagnostic performance was evaluated using logistic regression models, achieving an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.856 for distinguishing BC from healthy controls and 0.742 for differentiating BC from benign tumors [53]. Notably, combining these methylation markers with mammography and ultrasound improved diagnostic performance (AUC=0.898) [53]. A prognostic model based on six methylation sites was associated with poor overall survival (HR=2.826) [53]. Functional validation through in vitro experiments demonstrated that FAM126A overexpression regulates malignant phenotypes in BC cells [53].

Protocol for Multi-Feature Analysis in Pancreatic Cancer

A 2025 multi-center study developed integrated models for early detection and prognosis of pancreatic cancer using multiple cfDNA features [52]. The experimental workflow is illustrated below:

Cohort Design and Sample Preparation: The study enrolled 975 individuals across multiple centers, divided into Training (n=432), Testing (n=267), and two External Validation cohorts (n=129 and n=139) [52]. The cohorts included patients with pancreatic cancer, pancreatic benign tumors, chronic pancreatitis, and healthy controls [52]. Plasma cfDNA was extracted and subjected to low-pass whole-genome sequencing [52].

Multi-Feature Analysis: Four types of cfDNA features were analyzed: fragmentation patterns, end motifs, nucleosome footprint (NF), and copy number alterations (CNA) [52]. Pancreatic cancer patients showed significantly shorter cfDNA fragments (median 175 bp) compared to non-cancer groups (median 182-186 bp) [52]. KEGG pathway analysis of NF data revealed enrichment in cancer-related pathways including hedgehog, VEGF, MAPK, and Wnt signaling [52].

Model Development and Validation: The least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) was used to select predictive features [52]. A weighted diagnostic model (PCM score) and a prognostic evaluation model (PCP score) were developed [52]. The combined PCM model demonstrated superior performance across all cohorts, with AUCs of 0.979 in the Testing cohort and 0.992 and 0.986 in the External Validation cohorts [52]. For early-stage (I/II) disease, the model achieved an AUC of 0.994 compared to healthy controls [52].

Performance Comparison of Liquid Biopsy Approaches

The quantitative performance of various liquid biopsy approaches across different cancer types is summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Liquid Biopsy Approaches Across Cancer Types