The Gut Microbiome as an Epigenetic Regulator: Molecular Mechanisms, Research Methodologies, and Therapeutic Applications

This article synthesizes current research on the dynamic interplay between the gut microbiome and the host epigenome, a field with profound implications for precision medicine.

The Gut Microbiome as an Epigenetic Regulator: Molecular Mechanisms, Research Methodologies, and Therapeutic Applications

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on the dynamic interplay between the gut microbiome and the host epigenome, a field with profound implications for precision medicine. It explores foundational molecular mechanisms, including microbial metabolite signaling via short-chain fatty acids and one-carbon metabolism, and details advanced methodological approaches such as single-cell multi-omics and AI-driven modeling. For a specialist audience of researchers and drug development professionals, the content further addresses critical challenges in research standardization and troubleshooting, validates findings through disease-specific models in cardiology, neurology, and psychiatry, and evaluates comparative therapeutic strategies like live biotherapeutics and fecal microbiota transplantation. The synthesis aims to bridge foundational science with translational clinical applications.

Decoding the Dialogue: Foundational Mechanisms of the Microbiome-Epigenome Axis

The bidirectional epigenome-microbiome axis represents a dynamic and complex communication network between the host's epigenetic machinery and gut microbiota. This axis facilitates a continuous molecular dialogue where gut microorganisms influence host gene expression through epigenetic modifications, while the host's epigenome shapes the microbial ecosystem. This review synthesizes current mechanistic insights, profiling methodologies, and translational applications of this axis, framing it within the broader context of gut microbiome's impact on host epigenome research. We provide detailed experimental protocols, analytical frameworks, and visualization tools to equip researchers with practical methodologies for investigating this emerging field.

Core Concepts and Definitions

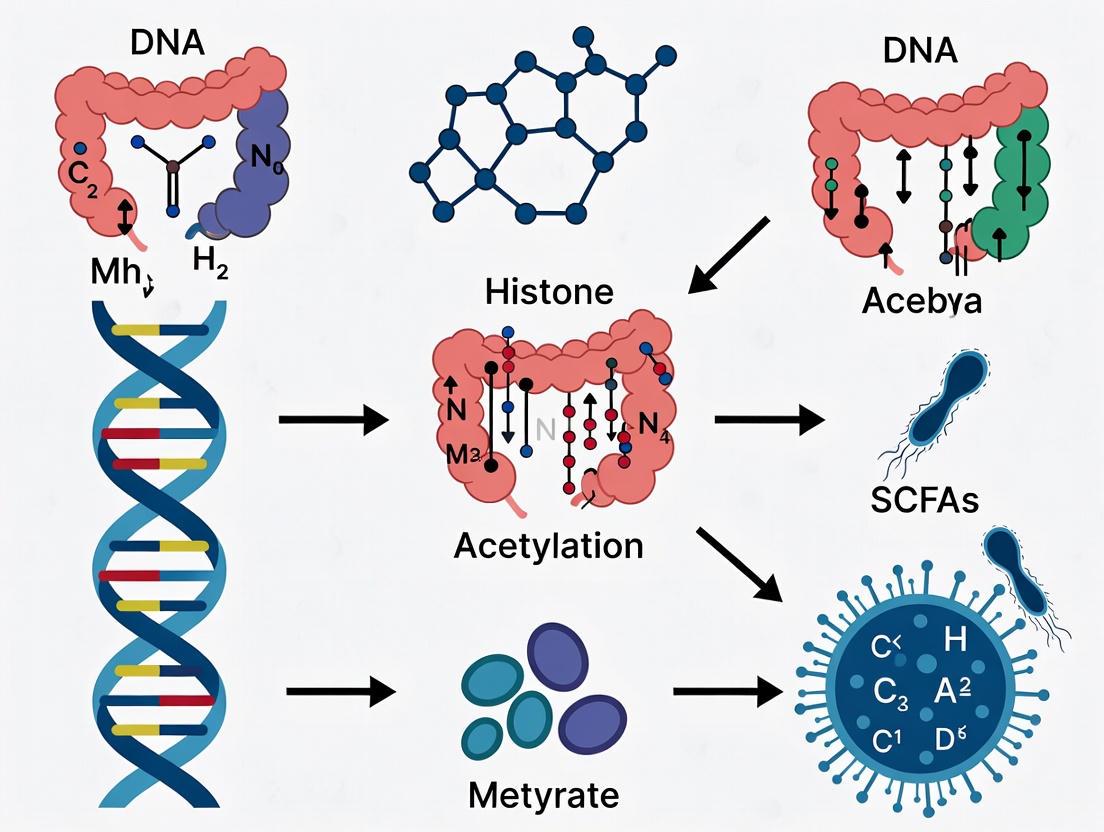

The epigenome-microbiome axis constitutes a bidirectional interface where environmental signals are translated into stable physiological responses. Epigenetics refers to heritable phenotypic changes that occur without alterations to the DNA sequence itself, primarily through three core mechanisms: DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNA-associated gene silencing [1] [2]. The gut microbiome, a metabolically active consortium of bacteria, viruses, fungi, and other microorganisms, profoundly influences host physiology through this epigenetic interface [2].

This relationship is fundamentally bidirectional. While host epigenetic states can shape microbial composition, microbial communities reciprocally influence host epigenetic regulation through diet- and environment-dependent mechanisms [3] [2]. This reciprocity embeds environmentally induced variation, which may influence the adaptive evolution of host-microbe interactions within a holo-omic framework [3].

Molecular Mechanisms of Interaction

Microbial Metabolites as Epigenetic Regulators

Gut microbiota-derived metabolites (MDMs) form a diverse repertoire of molecules that uniquely interact with host epigenetic machinery, establishing what has been termed the "MDMs–epigenetic (MDME) axis" [4]. These metabolites function as key epigenetic modifiers through several conserved pathways.

Table 1: Key Microbial Metabolites and Their Epigenetic Functions

| Metabolite Class | Major Producing Bacteria | Epigenetic Mechanism | Biological Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs) | Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes | Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibition; DNA methyltransferase modulation [1] [5] | Altered chromatin structure; gene expression changes in immunity/metabolism [2] |

| Folates | Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus | Donors for one-carbon metabolism, influencing DNA methylation [1] | Regulation of DNA synthesis and repair |

| Polyamines | Wide range of gut bacteria | Modulators of histone and DNA methyltransferase activity [1] [2] | Cellular growth, differentiation |

| Choline/Trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) | Metabolic conversion by gut microbiota | Alters host cholesterol metabolism and gene methylation [5] | Impact on metabolic and inflammatory diseases |

Specific Epigenetic Mechanisms

DNA and RNA Methylation: Microbial signals can modulate both DNA and RNA methylation patterns. DNA methylation typically involves the addition of a methyl group to cytosine, forming 5-methylcytosine (5mC), which regulates gene expression. Similarly, RNA modifications like N6-methyladenosine (m6A) influence RNA stability and translation [1] [2]. Butyrate, a well-studied SCFA, acts as a potent inhibitor of histone deacetylases (HDACs), leading to increased histone acetylation and altered gene transcription [5].

Bacterial Epigenetics: Bacteria possess their own epigenetic systems, primarily involving DNA methylation—N6-methyladenine (6mA), N4-methylcytosine (4mC), and 5-methylcytosine (5mC)—which function within restriction-modification systems and influence virulence, host colonization, and antibiotic resistance [2] [6]. This adds a layer of complexity to the bidirectional communication.

Research Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Profiling Host Epigenomic Modifications

Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS): This is the gold standard for mapping DNA methylation at single-base resolution.

- Protocol: Genomic DNA is treated with sodium bisulfite, which converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils, while methylated cytosines remain unchanged. The treated DNA is then sequenced, and the methylation status is determined by aligning sequencing reads to a reference genome and calculating the ratio of converted vs. unconverted cytosines at each CpG site [6].

- Applications: Ideal for generating comprehensive methylomes of host tissues in response to microbial changes.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing (ChIP-seq): This method identifies genome-wide histone modifications and transcription factor binding sites.

- Protocol: Cells or tissues are cross-linked with formaldehyde. Chromatin is sheared and immunoprecipitated with antibodies specific to a histone modification (e.g., H3K27ac). The immunoprecipitated DNA is then sequenced and mapped to the genome to identify enriched regions [2].

Analyzing Bacterial Methylomes and Composition

Single-Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) Sequencing: A third-generation sequencing technology that directly detects DNA methylation without chemical pre-treatment.

- Protocol: DNA is sequenced in real-time by observing the incorporation of fluorescently labeled nucleotides. The kinetics of nucleotide incorporation are altered by base modifications, allowing for the direct detection of 6mA, 4mC, and 5mC across the entire bacterial genome [6].

- Applications: Essential for characterizing the epigenomes of individual bacterial species within a community, identifying active restriction-modification systems, and understanding bacterial virulence.

Nanopore Sequencing: Another third-generation technology that detects methylation through changes in ionic current as DNA strands pass through a protein nanopore.

- Protocol: Native DNA is sequenced without amplification. Methylated bases cause characteristic disruptions in the current trace, which can be decoded using tools like Nanopolish or DeepSignal [6].

16S rRNA and Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing: These methods are used to profile microbial community composition and functional potential.

- Protocol for 16S rRNA Sequencing: The 16S rRNA gene is amplified from community DNA and sequenced. Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) are clustered to identify taxa present.

- Protocol for Shotgun Metagenomics: Total community DNA is randomly sheared and sequenced, providing insights into both taxonomic composition and functional gene content.

Data Integration and Visualization

Visualizing Repeated Measures Microbiome Data: Longitudinal studies require specialized techniques to account for within-subject correlations.

- Method: A framework using Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) adjusted via Linear Mixed Models (LMM) is recommended. The pairwise similarity matrix is calculated, and potential confounding effects are regressed out from each principal component of the similarity matrix using LMMs. The adjusted similarity matrix is then reconstructed from the model residuals for final PCoA visualization [7]. This effectively highlights microbial community variations related to the variable of interest while minimizing noise from confounders and repeated measures.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Epigenome-Microbiome Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) | Essential methyl donor for DNA and RNA methylation reactions in both host and bacteria [6]. | Stability and concentration are critical for in vitro methylation assays. |

| Sodium Bisulfite | Chemical agent for converting unmethylated cytosine to uracil in WGBS protocols [6]. | Reaction conditions must be optimized to prevent DNA degradation. |

| HDAC Inhibitors (e.g., Trichostatin A) | Positive controls for studying histone acetylation; mimic the effect of microbial butyrate [5]. | Specificity for different HDAC classes should be considered. |

| Type-Specific Histone Modification Antibodies | For ChIP-seq to map specific histone marks (e.g., H3K4me3, H3K27ac) in host cells. | Antibody specificity and lot-to-lot consistency are paramount. |

| Methyl-Sensitive Restriction Enzymes (MSREs) | For enzyme-based profiling of DNA methylation states at specific genomic loci [6]. | Limited to the recognition sites of available enzymes. |

| Cell-Free Transcription–Translation Systems | For in vitro recreation of specific DNA methylation patterns to overcome R-M barriers [6]. | Enables multiplex DNA methylation testing. |

| Germ-Free (GF) Mouse Models | Animals devoid of all microorganisms, essential for establishing causal roles of microbiota [5] [8]. | Require highly specialized housing and breeding facilities. |

| Gnotobiotic Mice | GF mice colonized with defined microbial communities, allowing reductionist studies. | Community composition can be precisely controlled. |

Translational Applications and Future Directions

Understanding the epigenome-microbiome axis opens transformative possibilities for clinical medicine. Key translational frontiers include:

- Biomarker Discovery: Identifying microbial and epigenetic signatures for early disease detection and monitoring [1] [2]. For instance, DNA methylation within promoters of virulence genes in pathogens like Mycobacterium tuberculosis offers potential diagnostic biomarkers [6].

- Live Biotherapeutic Products (LBPs) and Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT): Precision manipulation of the microbiome to correct dysfunctional epigenetic programming in metabolic, neurological, and inflammatory diseases [1] [9].

- Microbiome-Informed Drug Development: Incorporating microbiome and epigenomic data into clinical trial designs to identify responsive subpopulations and understand mechanisms of drug action and resistance [1].

- Precision Nutrition: Developing dietary interventions tailored to an individual's microbiome to steer epigenetic outcomes toward health promotion [2].

Advancements in high-throughput methylation mapping, artificial intelligence, and single-cell multi-omics are accelerating our ability to model these complex interactions at an unprecedented resolution [1] [9]. However, this progress must be accompanied by rigorous standardization and ethical data governance, guided by frameworks such as the FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) and CARE (Collective benefit, Authority to control, Responsibility, Ethics) principles [1] [9].

The bidirectional epigenome-microbiome axis represents a fundamental paradigm for understanding how environmental factors, mediated through our microbial inhabitants, shape host physiology and disease susceptibility. The intricate molecular dialogue between microbial metabolites and the host's epigenetic machinery provides a mechanistic basis for the long-lasting effects of the microbiome. As profiling and engineering technologies continue to mature, the potential to harness this axis for precision medicine—developing diagnostics, therapeutics, and nutritional strategies tailored to an individual's unique microbial and epigenetic makeup—becomes increasingly tangible. This field promises to redefine our approach to health and disease by targeting the dynamic interface between our environment and our genome.

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), including acetate, propionate, and butyrate, are major metabolites produced by gut microbiota through the fermentation of dietary fiber. These compounds function as potent epigenetic regulators primarily through the inhibition of histone deacetylases (HDACs) and activation of histone acetyltransferases (HATs), thereby influencing chromatin structure and gene expression. This whitepaper examines the molecular mechanisms by which SCFAs mediate epigenetic modifications and their profound implications for host immune function, metabolic health, and disease susceptibility. Emerging evidence positions SCFAs as crucial mediators in the gut microbiome-epigenome axis, offering promising therapeutic avenues for inflammatory, autoimmune, and metabolic disorders through targeted dietary and microbial interventions.

The human gastrointestinal tract hosts a complex ecosystem of microorganisms, collectively known as the gut microbiota, which encodes a metabolic capacity far exceeding that of the human host [10] [11]. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), primarily acetate (C2), propionate (C3), and butyrate (C4), are produced in substantial quantities (reaching over 100 mM in the colon) through bacterial fermentation of indigestible dietary fibers [12] [13]. These metabolites serve as a critical link between dietary intake, microbial metabolism, and host physiology, forming the foundation of the gut microbiome-epigenome axis.

Beyond their roles in host energy metabolism, SCFAs function as potent signaling molecules that influence gene expression through epigenetic modifications—heritable changes in gene expression that do not alter the DNA sequence itself [10] [11]. The most significant mechanisms include direct inhibition of histone deacetylases (HDACs) and the recent discovery of their role in activating histone acetyltransferases (HATs) [14] [12]. This dual capacity to shape the host epigenetic landscape positions SCFAs as key regulators in maintaining health and modulating disease processes, offering novel insights into how dietary patterns and gut microbiota composition can systemically influence host physiology.

Molecular Mechanisms of SCFA-Mediated Epigenetic Regulation

Histone Deacetylase (HDAC) Inhibition

The classical mechanism underlying SCFA epigenetic function is the inhibition of histone deacetylase (HDAC) enzymes, particularly the zinc-dependent HDAC classes I, IIa, and IIb [14] [15]. HDACs normally remove acetyl groups from lysine residues on histone tails, resulting in a more condensed, transcriptionally repressive chromatin state. By inhibiting HDAC activity, SCFAs lead to the accumulation of hyperacetylated histones, promoting an open chromatin configuration that facilitates gene transcription [14].

Among SCFAs, butyrate demonstrates the most potent HDAC inhibitory activity, with half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of approximately 0.09 mM in nuclear extracts from HT-29 human colon carcinoma cells [15]. Propionate exhibits weaker inhibition, while acetate shows minimal HDAC inhibitory effects at physiological concentrations [14] [15]. This HDAC inhibition is not limited to histone substrates but also affects numerous non-histone proteins, including transcription factors and signaling molecules, thereby amplifying the biological impact of SCFAs [14].

Table 1: HDAC Inhibitory Potency of SCFAs

| SCFA | IC50 Value | Experimental System | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Butyrate | 0.09 mM | HT-29 human colon carcinoma cell nuclear extracts | [15] |

| Propionate | Less potent than butyrate | HT-29 human colon carcinoma cell nuclear extracts | [15] |

| Acetate | Minimal inhibition | HT-29 human colon carcinoma cell nuclear extracts | [15] |

Histone Acetyltransferase (HAT) Activation

Recent research has revealed a more complex picture of SCFA epigenetic activity, challenging the historical focus on HDAC inhibition as the primary mechanism. A landmark study demonstrated that propionate and butyrate induce histone hyperacetylation primarily through activation of the acetyltransferase p300, rather than solely through HDAC inhibition [12].

The proposed mechanism involves the intracellular conversion of SCFAs to their corresponding acyl-CoAs (propionyl-CoA and butyryl-CoA), which then act as cofactors to auto-acylate p300's autoinhibitory loop. This autoacylation relieves enzymatic autoinhibition, thereby activating p300 for histone and protein acetylation [12]. This discovery fundamentally shifts our understanding of how SCFAs influence the epigenetic landscape, revealing a previously unknown mechanism of HAT activation that explains global chromatin changes in response to SCFAs.

Novel Histone Acylations

Beyond conventional acetylation, SCFAs contribute to a growing family of short-chain lysine acylations on histones, including propionylation (Kpr) and butyrylation (Kbu) [12] [16]. These modifications occur when SCFAs are converted to their corresponding acyl-CoAs and are incorporated into histones by HATs, which can utilize these cofactors with similar efficiency to acetyl-CoA [16].

Genome-wide mapping studies have revealed that these novel acyl marks (H3K18pr, H3K18bu, H4K12pr, and H4K12bu) are associated with genomic regions distinct from their acetyl counterparts and are enriched at promoters of genes involved in growth, differentiation, and ion transport [16]. This suggests that SCFAs contribute to a complex epigenetic code where different acyl chains may recruit distinct reader proteins or differentially affect chromatin structure, enabling fine-tuned regulation of gene expression programs in response to metabolic inputs.

Figure 1: SCFA-Mediated Epigenetic Mechanisms. SCFAs from dietary fiber fermentation are converted to acyl-CoAs, which drive epigenetic changes through HDAC inhibition, HAT activation, and novel histone acylations, ultimately altering chromatin structure and gene expression.

Quantitative Analysis of SCFA Effects on Epigenetic Marks

The effects of SCFAs on the epigenome are concentration-dependent and exhibit distinct patterns across different compounds. Systematic quantification reveals specific dose-response relationships for various histone modifications.

Table 2: Quantitative Effects of SCFAs on Histone Modifications

| SCFA | Concentration | Histone Modification | Fold Change | Experimental System | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Propionate | 10 mM | H3K18 propionylation | 1.84× (p=0.0043) | CRC cells | [16] |

| Propionate | 10 mM | H4K12 propionylation | 1.75× (p=0.0017) | CRC cells | [16] |

| Propionate | 0.1 mM | Propionyl-CoA | 0.08→0.35 ng/10^6 cells | CRC cells | [16] |

| Butyrate | 10 mM | Butyryl-CoA | 0.04→0.08 ng/10^6 cells | CRC cells | [16] |

| Butyrate | 10 mM | Acetyl-CoA | 2.25-3.81× decrease | CRC cells | [16] |

Propionate supplementation demonstrates a clear dose-dependent effect on both histone propionylation marks and intracellular propionyl-CoA pools. At 10 mM concentration, propionate significantly increases H3K18pr and H4K12pr marks by approximately 1.8-fold and 1.75-fold, respectively [16]. Similarly, propionyl-CoA levels rise dramatically from 0.08 ng/10^6 cells at 0.1 mM to 0.59 ng/10^6 cells at 10 mM supplementation [16].

Butyrate exhibits a more complex metabolic effect, increasing butyryl-CoA levels while simultaneously decreasing acetyl-CoA pools by 2.25- to 3.81-fold at 1-10 mM concentrations [16]. This reduction in acetyl-CoA may represent an important regulatory mechanism by which butyrate influences the overall epigenetic landscape.

Experimental Approaches for Studying SCFA Epigenetic Regulation

In Vitro Cell Culture Models

Cell-based systems provide controlled environments for investigating SCFA epigenetic mechanisms. Common approaches include:

- Cell lines: HCT116 colon cells and HT-29 human colon carcinoma cells are frequently used due to their colorectal origin and relevance to SCFA physiology [12] [15].

- Treatment conditions: SCFAs (sodium butyrate, sodium propionate) are typically applied at concentrations ranging from 0.1 mM to 10 mM for time periods from 1 hour to 96 hours, depending on the specific readout [17] [18] [12].

- Stimulation protocols: Immune cell differentiation studies often combine SCFAs with polarizing cytokines (e.g., TGF-β, IL-6) and activation signals (CD40 antibody, LPS, CpG) to assess SCFA effects on specific immune cell populations [17] [18].

Analytical Methods for Epigenetic Characterization

Advanced analytical techniques enable comprehensive assessment of SCFA-induced epigenetic changes:

- Histone proteomics: Mass spectrometry-based methods allow simultaneous quantification of >70 histone post-translational modifications, providing a global view of epigenetic changes [12].

- Chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq): Genome-wide mapping of specific histone modifications (H3K18pr, H3K18bu, H4K12pr, H4K12bu) reveals their genomic distribution and association with regulatory elements [16].

- Metabolomic profiling: LC-MS/MS quantification of intracellular acyl-CoA levels (propionyl-CoA, butyryl-CoA, acetyl-CoA) correlates metabolite availability with epigenetic effects [16].

In Vivo and Disease Models

Translation to physiological contexts employs various animal models:

- Germ-free mice: Comparison with conventionally raised mice reveals microbiota-dependent epigenetic patterning [14] [12].

- Disease models: Collagen-induced arthritis (CIA), dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-induced colitis, and high-fat diet-induced obesity models assess SCFA therapeutic potential [18] [10].

- SCFA administration: Drinking water supplementation (e.g., 100 mM SCFAs) or encapsulated formulations (e.g., BLIPs - butyrate-loaded liposomes) improve bioavailability and reduce cytotoxicity [17] [12].

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for SCFA Epigenetic Research. Integrated approach combining in vitro models with comprehensive epigenetic analysis and in vivo validation to elucidate SCFA mechanisms and therapeutic potential.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for SCFA Epigenetic Studies

| Reagent/Method | Specifications | Application | Key Findings Enabled |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium Butyrate | 0.1-10 mM in cell culture; 100 mM in drinking water | HDAC inhibition; B10 cell induction | Promoted B10 cell generation; inhibited HDAC activity (IC50=0.09 mM) [18] [15] |

| Sodium Propionate | 0.1-10 mM in cell culture | p300 activation; histone propionylation | Induced histone hyperacetylation via p300 activation [12] [16] |

| BLIPs | Butyrate-loaded liposomes | Enhanced SCFA delivery | Reduced cytotoxicity while maintaining immunomodulatory effects on T cells [17] |

| ChIP-seq Antibodies | H3K18pr, H3K18bu, H4K12pr, H4K12bu | Genome-wide mapping of acyl marks | Identified unique genomic locations for SCFA-induced modifications [16] |

| HDAC Activity Assay | Boc-Lys(Ac)-AMC substrate | HDAC inhibition quantification | Established butyrate as most potent SCFA HDAC inhibitor [15] |

Biological Consequences and Functional Outcomes

Immune Cell Regulation

SCFAs directly shape immune responses through epigenetic reprogramming of key immune cell populations:

- Regulatory T Cell (Treg) Enhancement: Butyrate promotes Treg differentiation and function through HDAC inhibition, particularly targeting the Foxp3 locus, thereby strengthening immunological tolerance [17] [10].

- Th17 Suppression: Butyrate suppresses pro-inflammatory Th17 cell differentiation by reducing RORγt expression and IL-17 production through chromatin remodeling [17].

- B10 Cell Generation: Butyrate and pentanoate enhance regulatory B10 cell frequency and function through HDAC inhibitory effects that activate the p38 MAPK signaling pathway [18].

Intestinal Homeostasis and Barrier Function

As the primary site of SCFA production and absorption, the intestinal epithelium exhibits profound responses to SCFA epigenetic regulation:

- Barrier Integrity: Butyrate strengthens intestinal barrier function by enhancing expression of tight junction proteins through HDAC inhibition-mediated effects on gene expression [13].

- Mucosal Immunity: SCFAs promote IgA production and regulate immune cell homing to the gut, maintaining appropriate mucosal responses to commensals and pathogens [10].

- Metabolic Programming: Colonocytes utilize butyrate as their primary energy source, with SCFAs directing metabolic gene expression programs through epigenetic mechanisms [12] [13].

Systemic Metabolic and Inflammatory Regulation

Beyond the gut, SCFAs exert systemic effects through epigenetic mechanisms:

- Obesity and Insulin Sensitivity: SCFAs improve metabolic parameters in obesity models through epigenetic regulation of genes involved in glucose homeostasis and insulin signaling [10].

- Neuroimmune Interactions: Propionate demonstrates neuroprotective effects in Parkinson's disease models through GPR41-dependent mechanisms that may involve epigenetic components [13].

- Cancer Prevention: Butyrate's HDAC inhibitory activity suppresses proliferation and induces apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells, while promoting normal colonocyte health [14] [13].

SCFAs represent a crucial class of microbial metabolites that directly interface with the host epigenome through multiple complementary mechanisms. The traditional view of SCFAs as primarily HDAC inhibitors has been expanded by recent discoveries of their role in activating HATs and contributing to novel histone acylation marks. These epigenetic mechanisms enable SCFAs to fine-tune gene expression programs across tissues, particularly influencing immune cell differentiation, intestinal barrier function, and systemic metabolic regulation.

The therapeutic implications of SCFA epigenetic regulation are substantial, with potential applications in inflammatory diseases, autoimmune conditions, metabolic disorders, and cancer. Future research directions should focus on elucidating the specific reader proteins that recognize SCFA-induced histone modifications, developing tissue-specific SCFA delivery systems, and exploring personalized nutritional approaches based on individual microbiome and epigenome profiles. As our understanding of the gut microbiome-epigenome axis deepens, SCFA-based interventions represent a promising frontier for precision medicine approaches that harness dietary components and microbial metabolites for disease prevention and treatment.

The gut microbiome serves as a critical interface between host nutrition and epigenetic regulation. This review elucidates the mechanisms by which gastrointestinal microbiota synthesize, utilize, and modulate the availability of key one-carbon (1-C) metabolism substrates—folate and vitamin B12—thereby influencing the host's epigenetic landscape. We explore how microbial contributions to methyl donor pools directly impact DNA methylation, histone modification, and non-coding RNA expression, with significant implications for host health and disease states. The integration of quantitative data on microbial metabolic capabilities, alongside standardized experimental protocols and essential research tools, provides a comprehensive resource for investigators exploring the microbiota-epigenome axis.

One-carbon (1-C) metabolism comprises an interconnected network of biochemical pathways—the folate cycle, methionine cycle, and transsulfuration pathway—that operate across cellular compartments to generate 1-C units essential for molecular biosynthesis, redox defense, and epigenetic regulation [19]. A crucial function of this system is the production of S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), the universal methyl donor required for DNA and histone methylation processes that orchestrate gene expression without altering the DNA sequence itself [19] [20]. The proper functioning of 1-C metabolism is fundamentally dependent on specific dietary nutrients and metabolites, including folate, vitamin B12, choline, betaine, and homocysteine [19].

Emerging evidence positions the gut microbiome as a central modulator of 1-C metabolism. Resident gastrointestinal bacteria directly contribute to host methyl donor availability through de novo synthesis of folate and vitamin B12, consumption of these compounds for their own metabolic needs, and production of metabolites that influence host metabolic pathways [21] [22]. This microbial influence creates a dynamic pathway through which environmental factors, particularly diet, can shape the host epigenome. Understanding these complex interactions is paramount for elucidating the pathophysiology of various diseases and developing novel therapeutic strategies targeting the microbiota-epigenome axis [22].

Microbial Contribution to Folate and Vitamin B12 Availability

Folate Synthesis and Utilization by Gut Microbiota

Folate (vitamin B9) is a essential water-soluble vitamin that functions as a critical cofactor in 1-C transfer reactions. While humans cannot synthesize folate endogenously and must obtain it from dietary sources or microbiota, numerous gut bacteria possess the enzymatic machinery for de novo folate biosynthesis [19] [21].

Key Aspects of Microbial Folate Metabolism:

- Synthesis and Bioavailability: Certain gut microbial species, including lactobacilli and bifidobacteria, can synthesize folates de novo. However, the bioavailability of microbially produced folates for the host depends on their form and location (luminal versus mucosal) [21].

- Absorption Dynamics: Dietary folates are hydrolyzed to their monoglutamated forms in the small intestine, a process facilitated by gut microbiota through enzymes like γ-glutamyl hydrolase (GGH) and glutamate carboxypeptidase II (GCPII), enabling absorption [19].

- Regulation of Host Status: The gut microbiome composition can influence host folate status by modulating the balance between synthesis and consumption of folate within the intestinal lumen, potentially affecting systemic folate levels and, consequently, methyl donor availability for epigenetic processes [21].

Vitamin B12 Dynamics in the Gut Microbiome

Vitamin B12 (cobalamin) is a complex organometallic compound synthesized exclusively by certain bacteria and archaea. It serves as an essential cofactor for two human enzymes: methionine synthase and L-methylmalonyl-CoA mutase [21] [23]. Its metabolism within the gastrointestinal tract represents a complex interplay between host and microbes.

Key Aspects of Microbial Vitamin B12 Metabolism:

- Synthesis and Competition: While some gut microbes produce vitamin B12, others are consumers. This can lead to competition for the vitamin between the host and specific bacterial species, potentially influencing host B12 status [21].

- Analog Production: Vitamin B12 not absorbed in the ileum reaches the colon, where gut bacteria convert approximately 80% into analogs (cobamides) with limited or no known vitamin activity in humans, altering the functional availability of B12 [21].

- Gene Regulation in Bacteria: Vitamin B12 is required for over a dozen enzymes in bacteria and regulates bacterial genes through B12-responsive riboswitches, making its availability a determinant of microbial community structure and function [21].

Table 1: Bacterial Genera Involved in Folate and Vitamin B12 Metabolism

| Bacterial Genus/Group | Role in 1-C Metabolism | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Lactobacillus | Folate synthesis | Contributes to host folate availability; potential probiotic candidate [21] |

| Bifidobacterium | Folate synthesis | Contributes to host folate availability; potential probiotic candidate [21] |

| Methanobrevibacter | Vitamin B12 synthesis (Archaea) | May compete with host for dietary B12 or provide it in certain contexts [22] |

| Bacteroidetes | Mixed (B12 consumers/producers) | High demand for B12; major competitors for available B12 [21] |

| Firmicutes | Mixed (B12 consumers/producers) | Includes both producers and consumers; affects net B12 balance [21] [22] |

| Akkermansia | Mucin degradation | Indirectly affects 1-C metabolism by influencing gut barrier integrity and inflammation [22] |

| Faecalibacterium | Butyrate production | Indirectly affects 1-C metabolism via anti-inflammatory effects and gut health [22] |

Impact on Host Epigenetic Mechanisms

The microbial modulation of folate and vitamin B12 availability has direct consequences for host epigenetic regulation, primarily through the provision of methyl groups for SAM-dependent methylation reactions.

- DNA Methylation: SAM donates methyl groups to DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) for cytosine methylation in CpG islands. Deficiencies in folate or B12 can lead to hyperhomocysteinemia and reduced SAM production, potentially causing global DNA hypomethylation and altered gene-specific methylation patterns [19] [20]. This is critically important during periods of rapid cellular division, such as embryonic development [19].

- Histone Modification: SAM is the methyl donor for histone methyltransferases (HMTs). Changes in methyl donor availability can modify histone methylation marks (e.g., H3K4me3 for activation, H3K9me3 for repression), thereby altering chromatin structure and gene accessibility [19] [22].

- Intergenerational and Developmental Programming: The periconceptional period is particularly sensitive to methyl donor supply. Maternal nutrition and gut microbiome composition can influence the epigenetic reprogramming of the embryo, with potential lifelong consequences for offspring health, as posited by the "Developmental Origins of Health and Disease" hypothesis [19].

The diagram below illustrates the core pathways of host 1-C metabolism and the specific points of microbial influence.

Diagram 1: Microbial Influence on Host 1-C Metabolism and Epigenetics. The gut microbiome contributes directly by synthesizing folate and B12, and indirectly by producing B12 analogs that may compete with host uptake. MTHFR: Methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase.

Experimental Methodologies for Investigating Microbial-Epigenetic Interactions

Studying the specific contributions of the gut microbiome to host methyl donor availability and epigenetic marks requires integrated, multi-omics approaches.

Characterizing Microbial Community Structure and Functional Potential

- 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing: This standard method assesses microbial community composition (β-diversity) and diversity within a sample (α-diversity). It can identify shifts in microbial populations associated with altered folate or B12 status [21] [22].

- Protocol: Amplify the V3-V4 hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene using primers 341F (5'-CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3') and 805R (5'-GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC-3'). Sequence on an Illumina MiSeq platform. Process data using QIIME2 or Mothur to assign operational taxonomic units (OTUs) and perform diversity analyses [21] [22].

- Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing: This provides higher resolution by sequencing all microbial DNA in a sample, allowing for direct assessment of the genetic potential for folate and B12 synthesis (e.g., presence of folP, cob genes) and utilization [21].

- Protocol: Extract total DNA from fecal samples. Prepare libraries without PCR amplification to reduce bias. Sequence on an Illumina NovaSeq platform. Analyze using HUMAnN2 or MetaPhlAn2 for taxonomic profiling and pathway analysis (e.g., MetaCyc pathways for folate and B12 metabolism) [21].

- Metatranscriptomics: RNA-based sequencing reveals the actively expressed genes within the microbiome, distinguishing between functional potential and actual activity in folate and B12 pathways [21].

Assessing Host Epigenetic Modifications

- Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Analysis (Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing - WGBS): This is the gold standard for quantifying DNA methylation at single-base resolution across the entire genome.

- Protocol: Extract genomic DNA from host tissues (e.g., blood, intestinal mucosa). Treat DNA with sodium bisulfite, which converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils (read as thymines), while methylated cytosines remain unchanged. Sequence the converted DNA and align to a reference genome to determine methylation status at each CpG site. Differential methylation analysis can be performed using tools like MethylKit or DSS [22].

- Histone Modification Profiling (Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing - ChIP-seq): This identifies genomic regions bound by specific histone modifications.

- Protocol: Cross-link proteins to DNA in cells or tissues. Sonicate chromatin to fragment. Immunoprecipitate the cross-linked DNA-protein complexes using antibodies specific to a histone mark (e.g., H3K4me3, H3K27me3). Reverse cross-links, purify DNA, and prepare libraries for sequencing. Analyze enriched regions to understand how methyl donor availability influences the histone landscape [22].

The following workflow diagram outlines the process of an integrated analysis to connect microbiome data with host epigenetics.

Diagram 2: Integrated Workflow for Microbial-Epigenetic Studies. This pipeline connects microbiome characterization with host epigenetic analyses to establish functional relationships.

Intervention Studies: From Correlation to Causation

- Gnotobiotic Mouse Models: Germ-free mice colonized with defined microbial communities (including communities that differ in their folate or B12 synthesis capabilities) allow for direct testing of microbial functions on host methyl donor metabolism and epigenetics [21] [22].

- Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT): Transplanting fecal microbiota from human donors (e.g., with defined nutritional status or disease) into germ-free or antibiotic-treated mice can demonstrate causal effects of a microbial community on host phenotype, including epigenetic endpoints [22].

- Targeted Nutritional Interventions: Supplementation with rumen-protected methyl donors (e.g., folate, methionine, choline, betaine) or vitamin B12 in controlled studies, while monitoring changes in the gut microbiome, host 1-C metabolites (e.g., plasma homocysteine, SAM), and tissue-specific epigenetic marks [19] [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methodologies

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Resources for Investigating Microbial-Epigenetic Interactions

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Rumen-Protected Methyl Donors | Oral delivery of methyl donors (e.g., folate, choline, methionine) to the lower GI tract with minimal upper GI absorption, allowing direct modulation of the gut microbiome [20]. | Studying the direct effect of methyl donors on microbial composition and host epithelial epigenetics in animal models. |

| Vitamin B12 Assay Kits (ELISA/EIA) | Quantification of total vitamin B12 (and analogs) in serum, plasma, or fecal samples. | Correlating systemic or local B12 status with microbial metabolic potential and host DNA methylation patterns. |

| Folate Microbiological Assay | Microbiological quantification of folate using Lactobacillus casei, which responds to biologically active folate forms. | Measuring functional folate levels in biological samples to assess microbial contribution. |

| S-Adenosylmethionine (SAM) & S-Adenosylhomocysteine (SAH) ELISA Kits | Precise measurement of SAM and SAH levels in tissues or plasma. The SAM:SAH ratio is a key indicator of cellular methylation capacity. | Linking microbial-modulated methyl donor availability to the host's functional methylation potential. |

| Methylated DNA Immunoprecipitation (MeDIP) Kits | Antibody-based enrichment of methylated DNA sequences for downstream analysis (e.g., qPCR, sequencing). | Profiling DNA methylation in specific genomic regions of interest (e.g., imprinting control regions) in response to microbial shifts. |

| B12-Depleted Animal Diets | Defined diets for creating B12 deficiency in animal models to study the subsequent effects on the gut microbiome and host epigenome. | Isolating the role of B12 in maintaining microbial communities and epigenetic homeostasis. |

| BioRender | Online tool with a vast library of scientifically accurate icons and templates for creating publication-quality figures and diagrams [24]. | Visualizing complex metabolic pathways, experimental designs, and microbial-host interactions. |

The gut microbiome is an integral and modifiable component of the host's one-carbon metabolism network, significantly influencing the availability of folate and vitamin B12 for epigenetic programming. The experimental frameworks and tools detailed herein provide a roadmap for deciphering the precise mechanisms underlying this interaction. Future research leveraging multi-omic integration and targeted interventions will be crucial for translating this knowledge into novel microbiome-based diagnostics and therapeutics for a range of diseases linked to epigenetic dysregulation, from metabolic disorders to psychiatric illnesses.

The gut microbiome functions as a dynamic endocrine organ that profoundly influences host physiology. A key mechanism of this influence is through the modulation of the host epigenome—the collection of chemical modifications to DNA and histones that regulate gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence [1]. Within this framework, polyamine biosynthesis and extracellular vesicle (EV) communication have emerged as two pivotal, interconnected pathways. These pathways facilitate a continuous dialogue between gut microbiota and host cells, enabling microbial influence over host transcriptional programs and cellular functions. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of these pathways, detailing their mechanisms, experimental investigation, and implications for drug development.

Polyamine Biosynthesis in the Gut Microbiome

Core Pathways and Metabolites

Polyamines, primarily putrescine (PUT) and spermidine (SPD), are small, polycationic organic compounds ubiquitous in all living cells. They are crucial for cell proliferation, differentiation, and gene expression due to their ability to bind negatively charged macromolecules like DNA and RNA [25] [26]. In the gut, the lumen of the upper small intestine primarily obtains polyamines from the diet, whereas the colon relies heavily on microbial metabolism as a source [26].

Intracellular polyamine levels are stringently regulated via biosynthesis, catabolism, and transport. The core biosynthetic pathway in mammals and microbes originates from arginine. As shown in the pathway diagram, arginine is converted to ornithine, which ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) then decarboxylates to form putrescine. Spermidine and spermine are subsequently synthesized through the sequential addition of aminopropyl groups from decarboxylated S-adenosylmethionine (dcSAM) [25] [26].

However, gut microbiota exhibit unique and complex polyamine metabolic pathways that can span multiple bacterial species. Key bacterial pathways include:

- The Ornithine Decarboxylase Pathway: Prevalent in bacteria like Escherichia coli, where constitutive (speC) and inducible (speF) ornithine decarboxylases convert ornithine to putrescine [26].

- The Arginine Decarboxylase (ADC) Pathway: Arginine is first decarboxylated to agmatine, which is then hydrolyzed to N-carbamoylputrescine and finally to putrescine. This pathway is present in species like Campylobacter jejuni and Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron [26].

- The L-Aspartate-β-Semialdehyde (ASA) Pathway: A distinct pathway in certain bacteria like Campylobacter jejuni and many Bacteroides species, where putrescine is converted to carboxyspermidine and then to spermidine [26].

A recent stable isotope-resolved metabolomics (SIRM) study using [U-13C]-inulin revealed distinct 13C enrichment profiles for SPD and PUT in the human gut microbiome, indicating that the arginine-agmatine-SPD pathway contributes to SPD biosynthesis alongside the canonical spermidine synthase pathway [27].

Quantitative Polyamine Levels in Health and Disease

Polyamine levels are tightly regulated, and their dysregulation is associated with various disease states. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from recent research.

Table 1: Quantitative Data on Polyamine Levels in Health and Disease

| Metric | Healthy State | Disease State (Inflammatory Bowel Disease) | Context and Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fecal Putrescine (PUT) | ~791.2 μM [27] | Significantly higher in IBD patients [27] | Level in healthy adults; derived from gut microbiota [27] [26] |

| Fecal Spermidine (SPD) | ~56.8 μM [27] | Significantly higher in IBD patients [27] | Level in healthy adults; derived from gut microbiota [27] [26] |

| Plasma PUT | ~5.3 μM [27] | Information Not Specified | Level in healthy individuals [27] |

| Plasma SPD | ~0.6 μM [27] | Information Not Specified | Level in healthy individuals [27] |

| Key Bacterial Contributor | Bacteroides spp. [27] | Bacteroides spp. [27] | Identified as key contributors to polyamine biosynthesis via SIRM and in silico analysis [27] |

Connection to Host Epigenetic Regulation

Polyamines exert a direct influence on the host epigenome through several mechanisms:

- Nucleosome Condensation: By binding to DNA, polyamines can promote the condensation of nucleosomes, a process intrinsically linked to histone methylation and acetylation, thereby influencing chromatin accessibility and gene transcription [28].

- Histone Modification: Spermidine induces the expression of global regulators like LaeA and the α-NAC transcriptional coactivator in fungi, a mechanism connected to epigenetic modification of histones that controls the switch to secondary metabolite production [28].

- Methylation Cycle Interconnection: Polyamine biosynthesis is metabolically intertwined with the methionine cycle, which produces S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), the primary methyl donor for DNA and histone methyltransferases. The consumption of SAM in polyamine synthesis can directly influence the cellular capacity for epigenetic methylation [25].

Extracellular Vesicle-Mediated Communication

Biogenesis and Function of Bacterial Extracellular Vesicles

Bacterial extracellular vesicles (BEVs) are nanoscale lipid bilayer vesicles (typically 40-200 nm) secreted by both Gram-negative and Gram-positive gut bacteria [29] [30]. They are generated through the double invagination of the plasma membrane and the formation of intracellular multivesicular bodies (MVBs), which release intraluminal vesicles (exosomes) upon fusion with the plasma membrane [31].

BEVs carry a diverse cargo of proteins, nucleic acids (DNA, RNA), lipids, and metabolites from their parent cell [32]. Crucially, machine learning analysis of 16S rRNA data has revealed that the taxonomic composition of gut microbiota-derived EVs forms a distinct entity from the overall gut microbiota. This highlights that conventional microbiota composition analyses are insufficient to fully understand gut microbiota-host communication, and EVs must be reported separately [30].

BEVs as Vectors for Epigenetic Reprogramming

BEVs facilitate intercellular communication by transferring their bioactive cargo to recipient host cells, leading to functional changes and epigenetic reprogramming. The diagram below illustrates how BEVs modify the epigenome of a recipient host cell.

The following Dot language code defines the elements and relationships in the BEV-mediated epigenetic reprogramming process:

The specific epigenetic mechanisms are:

- Modulation of DNA Methylation: BEVs derived from leukemia cells have been shown to increase global DNA methylation in recipient cells. This occurs through the transfer of RNA that upregulates DNA methyltransferases (DNMT3a, DNMT3b), leading to hypermethylation and silencing of tumor-suppressor genes like P53 and RIZ1 [32].

- Delivery of Regulatory Non-Coding RNAs: BEVs are enriched with miRNAs and other non-coding RNAs. Upon delivery, these miRNAs can directly bind to and regulate host mRNA targets, representing a powerful form of post-transcriptional epigenetic regulation [31] [33].

- Transfer of Histone-Modifying Enzymes: Bioinformatic analyses suggest that BEV cargoes are enriched with mRNAs and proteins involved in histone acetylation, deacetylation, and ubiquitination, indicating a potential role in directly altering the histone landscape of host cells [32].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Tracking Polyamine Biosynthesis with Stable Isotope-Resolved Metabolomics (SIRM)

SIRM is a powerful approach for dynamically tracking the incorporation of labeled atoms into metabolites, enabling the elucidation of active metabolic pathways.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Microbiome Polyamine SIRM

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Source / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| [U-13C]-Inulin | Stable isotope tracer to track microbial metabolic pathways using an effective substrate for the gut microbiome. | IsoLife bv (≥97 atom % 13C) [27] |

| Fresh Human/Mouse Feces | Source of viable gut microbial cells for ex vivo incubations. | Donors with no recent antibiotics/probiotics [27] |

| Gifu Anaerobic Medium (GAM) | Culture medium for supporting the growth and activity of anaerobic gut microbes during incubation. | Hopebio Co., Ltd [27] |

| Anaerobic Glove Bags/Chambers | Provides an oxygen-free environment for sample processing and incubation to maintain microbiome vitality. | NPS Corporation; with anaerobic gas production bags [27] |

| N-(9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyloxy)succinimide (Fmoc-OSu) | Derivatization reagent for polyamines to enable their detection and analysis via LC-MS. | Sigma-Aldrich (purity ≥ 98.0%) [27] |

| Liquid Chromatography-High Resolution Mass Spectrometry (LC-HRMS) | Analytical platform for separating and detecting 13C-labeled polyamines and related metabolites with high precision. | N/A [27] |

Detailed SIRM Protocol:

- Fecal Microbiome Separation: Fresh fecal samples from healthy human donors or mice are collected and immediately transferred to an anaerobic glove bag. Samples are suspended in culture medium (e.g., GAM) and subjected to low-speed centrifugation (35 × g, 10 min) to remove large, undigested particles. The supernatant is then centrifuged at 865 × g for 10 min to pellet the microbial cells, which are washed and resuspended in fresh medium [27].

- Anaerobic Incubation with Tracer: The pelleted microbial cells are incubated anaerobically at 37°C for 24 hours in medium containing 2 g/L of [U-13C]-inulin. Control groups are incubated with unlabeled (12C) inulin [27].

- Sample Quenching and Metabolite Extraction: After incubation, samples are centrifuged to separate the culture medium from the microbial cells. The cells are immediately quenched with acetonitrile containing 0.2% formic acid. The culture medium is lyophilized, and the dried powder is reconstituted in acetonitrile with 0.2% formic acid [27].

- Derivatization of Polyamines: A 50 μL aliquot of the sample is mixed with 50 μL of carbonate buffer (pH 10.2) and 50 μL of 5 mM Fmoc-OSu solution in acetonitrile. The mixture is shaken at room temperature for 15 min. The reaction is quenched with formic acid, and the derivatized polyamines are extracted into ethyl acetate [27].

- LC-HRMS Analysis: The extracted samples are analyzed using LC-HRMS. The derivatization facilitates the sensitive detection and quantification of polyamines. The high mass resolution allows for the precise measurement of 13C enrichment in PUT, SPD, and related metabolites, revealing the active biosynthetic pathways [27].

Isolating and Analyzing Gut Microbiota-Derived EVs

The following workflow outlines the key steps for isolating and analyzing BEVs from fecal samples, which is critical for studying their epigenetic effects.

The following Dot language code defines the steps for isolating and analyzing BEVs:

Key Methodological Steps:

- EV Isolation: Differential ultracentrifugation is a standard method. Sequential centrifugation steps at increasing speeds (e.g., 2,000 × g to remove bacteria and debris, followed by 100,000 × g to pellet EVs) are used to isolate EVs from fecal supernatants or bacterial culture media [30].

- EV Characterization: Isolated EVs are characterized for size, concentration, and morphology using techniques like Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) [30].

- Taxonomic and Functional Profiling: 16S rRNA gene sequencing of the EV-associated DNA is performed and analyzed with bioinformatic tools and machine learning models to determine the taxonomic origin of the EVs and confirm their distinct nature from the whole microbiota [30]. The protein and RNA cargo is analyzed via proteomics and RNA sequencing to identify potential epigenetic effectors [32] [31].

Implications for Drug Development

The intricate pathways of polyamine metabolism and EV communication present novel targets for therapeutic intervention.

- Targeting Polyamine Metabolism in Leukemia: Functional alterations in polyamine metabolism are observed in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Promising therapeutic targets include MAT2A and PRMT5, enzymes at the crossroads of polyamine metabolism and epigenetic regulation. Selective inhibitors of these enzymes are under investigation [25].

- Polyamine Modulation in IBD: The finding that Bacteroides spp. drive upregulated polyamine levels in IBD opens avenues for precision therapies. Modulating the gut microbiome or specific bacterial pathways to normalize polyamine levels could be a strategy to manage intestinal inflammation [27].

- BEVs as Diagnostic Biomarkers and Drug Delivery Vehicles: The distinct molecular cargo of BEVs makes them excellent non-invasive biomarkers for diseases like cancer and IBD [32] [30]. Furthermore, their natural ability to cross biological barriers, including the blood-brain barrier, and their biocompatibility make them promising engineered platforms for targeted drug delivery, including for epigenetic therapies [29] [31] [33].

Polyamine biosynthesis and extracellular vesicle communication represent two fundamental, synergistic pathways through which the gut microbiome influences the host epigenome. Technical advances in SIRM and EV isolation/multi-omics are enabling researchers to deconstruct these complex interactions with unprecedented detail. For drug development professionals, a deep understanding of these pathways is no longer a niche interest but a critical component of developing next-generation therapeutics targeting epigenetic dysregulation in oncology, gastroenterology, and beyond.

The traditional view of the host epigenome as a system solely influenced by host genetics and environmental factors is undergoing a paradigm shift. Emerging evidence compellingly demonstrates that the gut microbiome serves as a crucial interface between the external environment and the host's internal genomic regulation, giving rise to the concept of the holoepigenome. This framework conceptualizes the host and its microbiome as an integrated, co-adaptive unit where microbial communities actively shape the host's epigenetic landscape, influencing physiology, disease susceptibility, and evolutionary potential [34] [35]. Within the broader context of gut microbiome research, understanding the holoepigenome is paramount for deciphering the mechanisms through which gut microbes exert their profound effects on host health and disease. This whitepaper delves into the molecular mechanisms of microbiome-epigenome crosstalk, outlines key experimental methodologies, and explores the therapeutic implications of targeting the holoepigenome, providing a technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals.

Core Mechanisms of Microbiome-Epigenome Crosstalk

The communication between the gut microbiota and the host epigenome is primarily mediated by a diverse array of microbially derived metabolites and components. These molecules influence all major epigenetic mechanisms, including DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNA expression [36] [4] [37].

Table 1: Key Microbiota-Derived Metabolites and Their Epigenetic Effects

| Metabolite/Component | Primary Microbial Sources | Epigenetic Target | Molecular Outcome & Functional Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs) | Faecalibacterium, Roseburia, Eubacterium (Firmicutes) [22] [36] | Histone Deacetylases (HDACs) [36] [38] | HDAC inhibition → Increased histone acetylation → Altered gene expression in immunity & metabolism [36] [38] |

| Folate | Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus [36] | DNA Methyltransferases (DNMTs) [36] | Donor for S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) → Altered DNA methylation patterns → shifts in host cell transcriptome [36] |

| Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) | Gram-negative bacteria (e.g., Escherichia, Bacteroides) [36] | DNA Methylation | Altered methylation of immune-related genes (e.g., TLR4) → modulation of inflammatory responses [36] |

| Genotoxins (e.g., Colibactin) | pks+ E. coli [39] | DNA Integrity | DNA double-strand breaks & crosslinks → replication stress → genomic instability in colon epithelial cells [39] |

The holoepigenome is not a static entity but a dynamic system responsive to dietary and environmental perturbations. For instance, a high-fat diet can reduce populations of butyrate-producing bacteria, thereby diminishing the pool of a critical endogenous HDAC inhibitor and fundamentally altering the host's epigenetic state [36]. This metabolic signaling represents a primary pathway through which the microbiome integrates environmental cues to fine-tune host gene expression.

Visualizing the Signaling Pathways and Workflows

The complex interactions within the holoepigenome can be visualized through key signaling pathways and standardized research workflows.

SCFA-Mediated Epigenetic Regulation

The following diagram illustrates the primary pathway through which microbiota-derived SCFAs, particularly butyrate, influence host gene expression by modulating histone acetylation.

Experimental Workflow for Holoepigenome Analysis

A typical integrated workflow for investigating the holoepigenome involves multi-omics data collection and correlation analysis, as outlined below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Models

Advancing holoepigenome research requires a specific toolkit of experimental models, reagents, and analytical techniques.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Models for Holoepigenome Studies

| Category | Item / Model | Key Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| In Vivo Models | Germ-Free (Gnotobiotic) Mice | Provides a microbiome-free baseline to assess causal effects of defined microbial communities on the host epigenome [36] [38]. |

| Genetically Engineered Mouse Models (e.g., Apcmin/+) | Used in conjunction with microbial interventions to study microbiome-epigenome interactions in disease contexts like colorectal cancer [39]. | |

| Experimental Interventions | Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) | Transfers entire microbial communities from donor to recipient to investigate their causal role in reshaping the host epigenome and phenotype [22]. |

| Antibiotic Cocktails | Depletes the gut microbiota to study the consequences of its absence on host epigenetic marks and gene expression [38]. | |

| Defined Microbial Consortia | Used to colonize gnotobiotic mice with a simplified, known community to dissect specific host-microbe interactions. | |

| Analytical Reagents & Kits | HDAC Inhibitors (e.g., Sodium Butyrate) | Pharmacological tools used in vitro to mimic the epigenetic effects of SCFAs and study downstream transcriptional effects [36]. |

| DNA Methylation Kits (e.g., for WGBS) | Reagents for genome-wide analysis of DNA methylation patterns (5mC) in host tissues following microbial manipulation [39] [40]. | |

| Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Kits | Kits for mapping histone modifications (e.g., H3K9ac, H3K27me3) in host cells in response to microbial signals [38]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and rigor in holoepigenome research, the following core protocols are essential.

Protocol for Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) in Murine Models

Objective: To directly test the causal impact of a donor microbiome on the recipient host's epigenome. Materials: Donor mice (e.g., disease model or specific genotype), recipient mice (germ-free or antibiotic-treated), anaerobic workstation, sterile PBS, homogenizer, gavage needles. Procedure:

- Donor Inoculum Preparation: Harvest fresh fecal pellets from donor mice. Weigh and resuspend in anaerobic, sterile PBS (e.g., 100 mg/mL). Homogenize thoroughly and filter through a sterile mesh to remove large particulates. Process and use the inoculum rapidly under anaerobic conditions to preserve microbial viability [22].

- Recipient Preparation: Recipient mice should be either germ-free or pre-treated with a broad-spectrum antibiotic cocktail in their drinking water for 2-3 weeks to deplete the endogenous microbiota.

- Transplantation: Administer the prepared donor inoculum (e.g., 200 µL) to each recipient mouse via oral gavage. Control groups should receive a vehicle (PBS) only.

- Post-FMT Monitoring: House recipients in appropriate caging and monitor for phenotypic changes. Collect fecal samples over time to verify engraftment of the donor microbiota via 16S rRNA sequencing.

- Endpoint Analysis: Euthanize mice and collect target tissues (e.g., colon, liver, brain). Analyze epigenetic marks (e.g., via WGBS or ChIP-seq) and correlate with microbial engraftment data [22].

Protocol for Assessing Microbiome-Induced DNA Damage

Objective: To evaluate the genotoxic potential of specific bacteria or communities on host epithelial cells. Materials: pks+ E. coli (test), pks- E. coli (control), human colonic epithelial cell line (e.g., HCT116), cell culture facilities, gamma-H2AX antibody for immunofluorescence. Procedure:

- Cell Culture & Infection: Culture colonic epithelial cells in standard conditions. At ~70% confluence, infect cells with either pks+ E. coli or an isogenic pks- control strain at a defined multiplicity of infection (MOI). Co-culture for 4-6 hours.

- DNA Damage Staining: Fix cells and permeabilize. Stain with a primary antibody against phospho-histone H2AX (gamma-H2AX), a sensitive marker for DNA double-strand breaks, followed by a fluorescently labeled secondary antibody. Counterstain nuclei with DAPI [39].

- Imaging & Quantification: Image cells using a fluorescence microscope. Quantify the number of gamma-H2AX foci per nucleus. A statistically significant increase in foci in pks+ E. coli-infected cells compared to controls indicates microbiota-induced DNA damage, a precursor to potentially stable epigenetic and genetic changes [39].

Implications for Drug Development and Therapeutic Innovation

The holoepigenome concept opens novel avenues for therapeutic intervention. Strategies can target the microbiome to indirectly steer the host epigenome toward a healthier state or target the host's epigenetic machinery that responds to microbial signals.

- Live Biotherapeutic Products (LBPs): Engineered bacterial strains, such as those producing high levels of SCFAs like butyrate, can be developed to deliver targeted epigenetic-modifying signals to the gut [22]. For example, increasing Faecalibacterium abundance could enhance HDAC inhibition, promoting an anti-inflammatory state.

- Precision Prebiotics and Diets: Nutritional interventions can be designed to selectively nourish beneficial taxa that produce favorable epigenetic metabolites. This approach leverages diet to manage the holoepigenome for chronic disease prevention and management [36].

- Epigenetic Drugs Informed by Microbiome: The efficacy of existing epigenetic drugs, such as HDAC inhibitors used in oncology, may be influenced by the patient's microbiome. Understanding this interaction could lead to microbiome-based biomarkers for drug response and the development of combination therapies that modulate both the microbiome and the epigenome [38] [39].

The evidence is compelling: the host and its microbiome function as a cohesive, co-adaptive unit—the holoepigenome—that is fundamental to understanding mammalian biology and disease etiology. The bidirectional communication, mediated largely by microbial metabolites, seamlessly integrates environmental cues with host gene regulation. Future research must focus on longitudinal human studies to track holoepigenome dynamics over time and in response to interventions, and on developing more sophisticated multi-omics integration tools to move from correlation to causation. For drug developers, the message is clear: the microbiome is not merely a passive passenger but an active participant in shaping the host's epigenetic landscape. Embracing this complexity is no longer optional but essential for pioneering the next generation of targeted, effective therapeutics.

From Bench to Bedside: Advanced Methodologies and Therapeutic Translation

The human gut microbiome, a complex ecosystem of bacteria, viruses, and fungi, profoundly influences host physiology through dynamic crosstalk with human cells. A key mechanism of this interaction is epigenetic regulation, where microbial metabolites and signals modify host gene expression without changing the underlying DNA sequence [1] [2]. These modifications include DNA methylation, histone modifications, and RNA methylation, which collectively regulate phenotypic plasticity and disease susceptibility [1] [41] [2]. Cutting-edge genomic tools are now unveiling the precise mechanisms of this interaction, revealing that microbial metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), polyamines, and nutrients from bacterial one-carbon metabolism serve as substrates and signals for host epigenetic machinery [1]. This review details the single-cell multi-omics and high-throughput methylation mapping technologies that are revolutionizing our understanding of the gut microbiome's impact on the host epigenome, providing a technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals.

Single-Cell Multi-Omic Technologies for Host-Microbe Analysis

scEpi2-seq: Simultaneous Profiling of Histone Modifications and DNA Methylation

Single-cell Epi2-seq (scEpi2-seq) is a groundbreaking method that enables the joint readout of histone modifications and DNA methylation in single cells, overcoming previous limitations of studying these marks in isolation [42].

- Core Principle: The technique leverages a pA–MNase fusion protein tethered to specific histone modifications (e.g., H3K9me3, H3K27me3, H3K36me3) via antibodies. After single-cell sorting and MNase digestion, the released fragments are processed for library preparation. A critical innovation is the use of TET-assisted pyridine borane sequencing (TAPS) for DNA methylation detection, which converts methylated cytosine (5mC) to uracil without damaging the adaptor sequences, unlike traditional bisulfite sequencing [42].

- Workflow Output: From each sequencing read, researchers can extract three key pieces of information:

- Histone mark location from mapped genomic positions.

- DNA methylation status from C-to-T base conversions.

- Nucleosome spacing from distances between sequencing read start sites [42].

- Performance Metrics: Applied to K562 cells, scEpi2-seq successfully profiled over 50,000 CpGs per single cell with high specificity (Fraction of Reads in Peaks/FRiP ranging from 0.72 to 0.88) and a C-to-T conversion rate of ~95% [42]. This allows for the direct observation of epigenetic interactions, such as the finding that regions marked by repressive histone marks H3K27me3 and H3K9me3 exhibit much lower DNA methylation levels (~8-10%) compared to regions marked by the active transcription-associated mark H3K36me3 (~50%) [42].

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics of scEpi2-seq in Model Cell Lines

| Parameter | K562 Cells | RPE-1 hTERT Cells |

|---|---|---|

| Cells Profiled | 2,660 across 3 histone marks | 3,420 across 3 histone marks |

| Cells Passing QC | 60.2% - 77.9% | 35.4% - 40.6% |

| CpGs Detected per Cell | > 50,000 | Data not specified |

| Average FRiP | 0.72 - 0.88 | Data not specified |

| TAPS Conversion Rate | ~95% | Data not specified |

Integrated Multi-Omic Analysis in Complex Tissues

The power of single-cell multi-omics extends to complex tissues and disease contexts, such as the intestinal mucosa, where host and microbiome interactions are direct. A seminal study on paediatric ulcerative colitis (UC) combined mucosal microbiome profiling with host epigenomics and transcriptomics from intestinal biopsies [43].

- Experimental Design: The study analyzed 201 biopsies from 56 treatment-naïve children with UC. Multi-omics data included:

- Mucosal Microbiome: 16S rRNA sequencing to determine microbial diversity and composition.

- Host Epigenome: DNA methylation profiling.

- Host Transcriptome: Gene expression profiling [43].

- Data Integration and Findings: Machine learning models integrating microbiome and epigenome data outperformed models using either dataset alone in predicting future clinical relapse. This integration revealed that children who relapsed had lower bacterial diversity and specific microbial shifts, including fewer butyrate producers (e.g., F. prausnitzii, E. rectale) and an increase in oral-associated bacteria like Veillonella parvula, which was shown to induce pro-inflammatory responses in experimental models [43]. This demonstrates how multi-omics can directly link specific microbial taxa to host immune responses and clinical outcomes through epigenetic and transcriptional pathways.

High-Throughput Methylation Mapping Platforms

The Methylation Screening Array (MSA): A Targeted, Ternary-Code Platform

The Methylation Screening Array (MSA) represents a conceptual shift in array-based epigenomics, moving from broad genomic coverage to targeted, trait-associated profiling with the ability to distinguish between cytosine modifications [44].

- Design Philosophy and Probe Content: Unlike previous arrays like the Illumina Infinium BeadChip, which prioritized wide genomic coverage, the MSA condenses probe content to 284,317 probes specifically curated and prioritized from over 1,000 EWAS publications and high-resolution methylome studies. This design enriches for trait-associated and cell-type-specific CpG sites, including those from rare cell types like neuronal subpopulations [44].

- Discrimination of 5mC and 5hmC: A major innovation of the MSA is its partnership with the bisulfite-APOBEC3A deamination (bACE-seq) protocol. This combination allows for the scalable dissection of the "ternary methylation code," generating matched profiles for total cytosine modification (5modC, representing 5mC + 5hmC) and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) from the same sample [44]. This is a significant advance because 5hmC, enriched in brain and other tissues, is a stable epigenetic mark with distinct regulatory roles but was previously indistinguishable from 5mC in standard bisulfite-based arrays.

- Utility in Context-Aware EWAS: The MSA's enriched content enables more accurate interpretation of EWAS findings within their tissue and cell-type context. For example, the platform demonstrates that CpGs associated with Alzheimer's disease show the most variable methylation in brain tissue, while those linked to irritable bowel syndrome are most dynamic in the colon [44].

Table 2: Comparison of Methylation Screening Array (MSA) with Illumina EPICv2

| Feature | Methylation Screening Array (MSA) | Illumina EPICv2 Array |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Probes | 284,317 | > 900,000 |

| Probe Selection Strategy | Trait-associated and cell-type-specific loci from curated literature/databases | Broad, even genomic coverage |

| CpG Context | Tertiary code (5mC, 5hmC, unmodified C) | Binary code (5modC vs. unmodified C) |

| 5hmC Detection | Yes, via integrated bACE-seq protocol | No |

| Primary Application | Trait-centric EWAS, functional screening | Broad discovery EWAS |

| Sample Throughput | 48-sample format | 96-sample format |

High-Throughput Methylation Analysis for Newborn Screening

Automated, high-throughput methylation analysis is also making its way into clinical screening applications. A 2025 study compared two automated systems for bisulfite conversion and quantitative melt analysis—the magnetic-bead-based IsoPure and the column-based QIAcube HT—for methylation-based newborn screening of fragile X syndrome (FMR1) and chromosome 15 imprinting disorders (SNRPN) from archival blood spots [45].

- Performance Comparison: Both methods achieved 100% diagnostic sensitivity and specificity on fresh samples. However, the IsoPure system demonstrated superior performance on archival samples stored for over 10 years, with significantly lower reaction failure rates (0.365% for SNRPN and 0.74% for FMR1) compared to the QIAcube HT (19.34% and 2.56%, respectively) [45]. This highlights the critical importance of platform selection when working with challenging sample materials like archival dried blood spots.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Single-Cell Multi-Omics and Methylation Mapping

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| pA-MNase fusion protein | Enzyme-antibody fusion that cleaves DNA around specific histone modifications. | Targeted chromatin cleavage in scEpi2-seq for mapping histone marks [42]. |

| TAPS Reagents | Enzymatic conversion kit for detecting 5mC without DNA degradation. | Gentle and efficient methylation calling in scEpi2-seq and MSA/bACE workflows [42] [44]. |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits | Chemical conversion of unmethylated cytosine to uracil for standard methylation analysis. | DNA methylation analysis in newborn screening and other bisulfite-dependent protocols [45]. |

| Methylation Screening Array (MSA) | Next-generation BeadChip for targeted, high-throughput profiling of 5mC and 5hmC. | Trait-centric EWAS in large cohort studies [44]. |

| Single-cell Bisulfite Sequencing Kits | Kits for whole-genome methylation sequencing at single-cell resolution. | Constructing methylation profiles of super-enhancers in muscle stem cells [46]. |

| ALLCools package | Bioinformatics tool for processing and analyzing single-cell methylation data. | Analysis of scBS-seq data to identify differentially methylated regions [46]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: scEpi2-seq for Joint Histone and DNA Methylation Profiling

This protocol outlines the key steps for simultaneous profiling of histone modifications and DNA methylation in single cells [42].

- Cell Preparation and Permeabilization: Harvest and wash cells. Permeabilize cells to allow antibody access to nuclear antigens.

- Antibody Incubation: Incubate cells with specific primary antibodies against the histone mark of interest (e.g., H3K27me3).

- pA-MNase Binding: Add the pA-MNase fusion protein, which binds to the primary antibodies.

- Single-Cell Sorting: Use Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) to sort individual cells into a 384-well plate containing a mild lysis buffer.

- MNase Digestion: Initiate targeted chromatin cleavage by adding Ca²⁺, the essential cofactor for MNase. This releases DNA fragments bound to the modified histones.

- Library Preparation for Chromatin Modality:

- Repair and A-tail the MNase-released DNA fragments.

- Ligate adaptors containing a single-cell barcode, a Unique Molecular Identifier (UMI), a T7 promoter, and Illumina sequencing handles.

- TAPS Conversion for Methylation Modality: Pool material from the 384-well plate and subject it to TET-assisted pyridine borane sequencing (TAPS). This step chemically converts 5mC to uracil, preserving the adaptor sequences.

- Final Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Perform in vitro transcription (IVT) from the T7 promoter.

- Conduct reverse transcription and PCR amplification to generate the final sequencing library.

- Sequence using paired-end sequencing on an Illumina platform.

Protocol: Super-Enhancer Methylation Analysis in Stem Cells

This protocol describes a bioinformatic workflow for identifying and analyzing the methylation profile of super-enhancers using public and newly generated data, as applied to skeletal muscle stem cells (MuSCs) [46].

- Data Acquisition:

- Download H3K27ac ChIP-seq data from the ENCODE database to define enhancer regions.

- Obtain single-cell bisulfite sequencing (scBS-seq) data from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) for methylation analysis.

- Super-Enhancer Identification:

- Use the ROSE software in a Python environment to identify super-enhancers from the H3K27ac ChIP-seq data.

- Rank enhancers by H3K27ac signal intensity, stitch enhancers within 12.5 kb, and identify the inflection point to define SEs.