The Epigenetic Triad: Decoding the Interplay of Non-Coding RNAs, DNA Methylation, and Histone Modifications

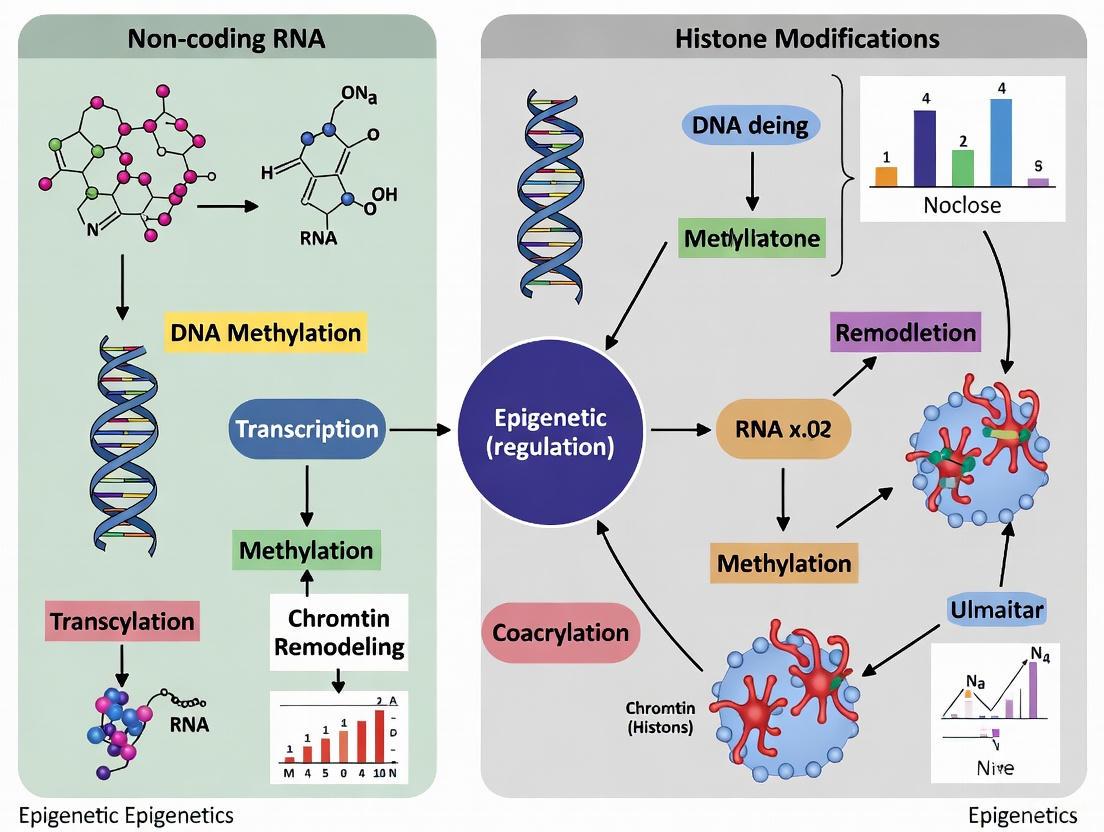

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the sophisticated crosstalk between non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), DNA methylation, and histone modifications—the core pillars of epigenetic regulation.

The Epigenetic Triad: Decoding the Interplay of Non-Coding RNAs, DNA Methylation, and Histone Modifications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the sophisticated crosstalk between non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), DNA methylation, and histone modifications—the core pillars of epigenetic regulation. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores foundational mechanisms where ncRNAs like miRNAs, lncRNAs, and circRNAs direct and are regulated by DNA and histone marks. It further delves into methodological approaches for investigating these networks, addresses key challenges in therapeutic targeting, and validates these interactions through disease-specific case studies in oncology, neurology, and reproductive health. The synthesis offers a roadmap for leveraging this integrated epigenetic understanding in diagnostic and therapeutic innovation.

Core Mechanisms: How Non-Coding RNAs Direct and Respond to DNA and Histone Marks

The central dogma of genetics has been fundamentally reshaped by the discovery that the majority of the human genome is transcribed into non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) that play critical roles in regulating gene expression without being translated into proteins [1] [2]. These ncRNAs form complex interplay with epigenetic mechanisms—including DNA methylation and histone modifications—to establish a sophisticated regulatory network that controls cellular fate, development, and disease progression [1] [3]. This regulatory crosstalk represents a hidden layer of genetic control that is highly responsive to environmental cues and represents a pivotal area of research for understanding disease pathogenesis and developing novel therapeutics [4]. The dynamic and reversible nature of these epigenetic modifications offers promising avenues for therapeutic intervention, particularly in complex diseases such as cancer, where epigenetic dysregulation is a hallmark feature [5] [2].

Non-Coding RNA Classification and Functions

Non-coding RNAs are broadly categorized based on their size, structure, and biological functions. The major classes include small ncRNAs (such as miRNAs, siRNAs, and piRNAs) and long ncRNAs (lncRNAs), each with distinct biogenesis pathways and mechanisms of action [1] [2].

Table 1: Major Classes of Non-Coding RNAs and Their Characteristics

| ncRNA Class | Size Range | Key Functions | Biogenesis Pathway | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miRNA | 20-25 nucleotides [1] | Post-transcriptional gene regulation [6] | Canonical (DROSHA/DGCR8, DICER) and non-canonical pathways [2] | mRNA degradation or translational repression via RISC complex [2] |

| siRNA | 19-24 nucleotides [1] | Genome defense, transcriptional silencing [7] | Dicer-dependent processing of long dsRNA [7] | RNA interference, transcriptional gene silencing [6] |

| piRNA | 26-31 nucleotides [1] | Transposon silencing, genome stability [6] | Dicer-independent, single-stranded precursors [1] | Complex formation with Piwi proteins, epigenetic regulation [1] |

| lncRNA | >200 nucleotides [5] | Chromatin remodeling, transcriptional regulation [6] | RNA Polymerase II/III transcription [1] | Scaffold, guide, decoy, or signal molecules [1] |

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) and Their Biogenesis

miRNAs are among the most extensively studied ncRNAs, functioning primarily as post-transcriptional regulators of gene expression. The canonical biogenesis pathway begins with RNA Polymerase II transcription of miRNA genes to produce primary miRNAs (pri-miRNAs) [2]. These pri-miRNAs are processed in the nucleus by the Microprocessor complex (comprising DROSHA and DGCR8) to form precursor miRNAs (pre-miRNAs) [4] [2]. After export to the cytoplasm via Exportin-5, pre-miRNAs are cleaved by DICER to generate mature miRNA duplexes [4]. One strand of this duplex is loaded into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), where it guides the complex to complementary mRNA targets, resulting in translational repression or mRNA degradation [2]. Non-canonical pathways, such as the mirtron pathway, bypass certain steps in this process, highlighting the diversity of miRNA biogenesis mechanisms [4].

Long Non-Coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and Their Diverse Roles

lncRNAs represent a vast and heterogeneous class of ncRNAs that exert their functions through diverse mechanisms. They can act as scaffolds for protein complexes, guides for chromatin-modifying enzymes, decoys that sequester regulatory molecules, or signals that mark specific genomic loci [1]. Their functions often depend on their subcellular localization—nuclear lncRNAs predominantly regulate chromatin organization and transcription, while cytoplasmic lncRNAs influence mRNA stability and translation [5]. According to genomic context, lncRNAs are classified as intergenic, intronic, antisense, bidirectional, or overlapping, which influences their regulatory characteristics [1].

DNA Methylation and Its Regulation by ncRNAs

DNA methylation involves the addition of a methyl group to the fifth carbon of cytosine residues, primarily within CpG dinucleotides, forming 5-methylcytosine (5mC) [5] [8]. This epigenetic mark is established and maintained by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs): DNMT3A and DNMT3B catalyze de novo methylation, while DNMT1 maintains methylation patterns during DNA replication [5] [9]. Active demethylation is facilitated by the TET enzyme family (TET1, TET2, TET3), which oxidizes 5mC to initiate DNA repair processes that replace methylated cytosines with unmethylated ones [5] [8]. DNA methylation patterns are highly dynamic and cell-type specific, with promoter methylation generally associated with transcriptional repression [5] [9].

ncRNA-Mediated Regulation of DNA Methylation

Emerging evidence reveals that ncRNAs, particularly lncRNAs, play crucial roles in directing DNA methylation patterns to specific genomic loci. This regulation occurs through several distinct mechanisms:

Direct Recruitment of DNMTs: Certain lncRNAs interact directly with DNA methyltransferases and guide them to target genomic regions. For instance, lncRNAs transcribed from rRNA genes form DNA:RNA triplexes that are recognized by DNMT3B, leading to epigenetic regulation of rDNA expression [5]. Similarly, lncRNA ADAMTS9-AS2 recruits DNMT1/3 to the CDH3 promoter in esophageal cancer, inhibiting cancer progression [5].

Indirect Recruitment Through Chromatin Modifiers: Some lncRNAs recruit DNMTs indirectly through interactions with intermediary proteins. A well-established mechanism involves the polycomb protein EZH2, which interacts with DNMTs and associates with DNMT activity [5]. LncRNAs such as HOTAIR can recruit PRC2 complexes containing EZH2 to specific genomic loci, leading to subsequent DNA methylation [5] [8].

Regulation of Demethylation Machinery: ncRNAs also influence DNA demethylation by interacting with TET enzymes. LncRNA Oplr16 binds to the Oct4 promoter and interacts with TET2, inducing DNA demethylation and gene activation [5]. Similarly, lncRNA MAGI2-AS3 recruits TET2 to the LRIG1 promoter in acute myeloid leukemia, inhibiting leukemic stem cell self-renewal [5].

Diagram 1: ncRNA Regulation of DNA Methylation. ncRNAs can recruit either DNMTs to establish DNA methylation or TET enzymes to remove it, ultimately influencing gene expression.

Histone Modifications and ncRNA Interplay

Histone modifications represent another crucial layer of epigenetic regulation that works in concert with ncRNAs. These post-translational modifications occur on the N-terminal tails of histone proteins and include acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination, among others [1] [3]. The combination of these modifications constitutes a "histone code" that determines chromatin structure and accessibility, thereby influencing gene expression patterns [1].

Table 2: Major Histone Modifications and Their Functional Consequences

| Modification Type | Histone Residues | Enzymes Involved | General Effect on Transcription |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetylation | H3K9, H3K14, H3K18, H3K27, H4K5, H4K8, H4K16 [3] | HATs, HDACs [3] | Activation (generally) [3] |

| Methylation | H3K4, H3K36, H3K79 (activation); H3K9, H3K27, H4K20 (repression) [1] | KMTs, PRMTs, KDMs [3] | Context-dependent [3] |

| Phosphorylation | H3S10, H3T45 [3] | Kinases, Phosphatases [3] | Activation (e.g., H3S10) [3] |

| Ubiquitination | H2AK119, H2BK120 [3] | E1/E2/E3 enzymes, DUBs [3] | Variable depending on context [3] |

ncRNA-Mediated Regulation of Histone Modifications

ncRNAs interact extensively with the histone modification machinery through several mechanisms:

Recruitment of Histone-Modifying Complexes: Many lncRNAs function as molecular scaffolds that recruit histone-modifying complexes to specific genomic loci. The well-characterized lncRNA HOTAIR, for example, interacts with both PRC2 (which catalyzes H3K27 methylation) and the LSD1/CoREST/REST complex (which demethylates H3K4me2), leading to transcriptional repression of target genes [8] [1].

Guide Mechanisms: lncRNAs can guide histone-modifying enzymes to specific genomic locations through complementary base pairing with DNA or RNA. This mechanism allows for precise targeting of epigenetic modifications to specific genes or regulatory elements [1].

Decoy Functions: Some ncRNAs act as molecular decoys that sequester histone-modifying enzymes, preventing them from interacting with their genomic targets. This competitive binding can alter the epigenetic landscape and influence gene expression programs [1].

Experimental Methodologies for Studying ncRNA-Epigenetic Interactions

Investigating the intricate relationships between ncRNAs and epigenetic regulators requires a combination of sophisticated molecular biology techniques and high-throughput approaches. The following table summarizes key experimental protocols used in this field.

Table 3: Key Experimental Methods for Studying ncRNA-Epigenetic Interactions

| Methodology | Application | Key Steps | Outcome Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| RIP-seq (RNA Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing) | Identify lncRNAs interacting with epigenetic regulators [5] | 1. Cross-link RNA-protein complexes2. Immunoprecipitate with target protein antibody3. Isplicate and sequence bound RNAs4. Bioinformatic analysis | Genome-wide identification of ncRNAs bound to specific epigenetic proteins |

| RAT-seq (RNA reverse transcription-associated trap sequencing) | Profile genome-wide interaction targets for lncRNAs [5] | 1. Reverse transcribe RNA targets2. Capture and sequence cDNA-mRNA hybrids3. Map interaction sites | Comprehensive mapping of lncRNA-genomic DNA interactions |

| 5-AZA-CdR Treatment Assays | Assess DNA methylation-dependent ncRNA expression [9] | 1. Treat cells with DNA methyltransferase inhibitor2. Measure ncRNA expression changes (e.g., by qRT-PCR)3. Correlate with methylation status | Identification of ncRNAs regulated by promoter methylation |

| Chromatin Conformation Capture | Study 3D chromatin interactions mediated by ncRNAs [5] | 1. Cross-link chromatin2. Digest with restriction enzymes3. Ligate cross-linked fragments4. Reverse cross-links and sequence5. Analyze interaction frequencies | Mapping of long-range chromatin interactions facilitated by ncRNAs |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ncRNA-Epigenetics Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNMT Inhibitors | 5-Aza-2'-deoxycytidine (5-AZA-CdR) [9] | Demethylating agent; inhibits DNA methyltransferases | Studying methylation-dependent regulation of ncRNAs [9] |

| HDAC Inhibitors | Trichostatin A, Vorinostat [3] | Inhibit histone deacetylases; increase histone acetylation | Investigating histone acetylation-ncRNA interactions |

| Antibodies for RIP | Anti-DNMT1, Anti-EZH2, Anti-TET2 [5] | Immunoprecipitation of epigenetic regulator complexes | Identification of ncRNAs bound to specific epigenetic regulators [5] |

| Methylation-Specific PCR Primers | Custom-designed primers for ncRNA promoters [9] | Amplify methylated vs. unmethylated DNA sequences | Assessment of ncRNA promoter methylation status |

| si/shRNA Libraries | DNMT-targeting, TET-targeting, ncRNA-specific [5] | Knockdown of specific epigenetic regulators or ncRNAs | Functional validation of ncRNA-epigenetic regulator interactions |

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Studying ncRNA-Epigenetic Interactions. A typical research pipeline begins with target identification, proceeds through screening and validation, and culminates in functional assays and integrative analysis.

Concluding Perspectives

The intricate interplay between ncRNAs, DNA methylation, and histone modifications represents a sophisticated regulatory network that fine-tunes gene expression in development, homeostasis, and disease. Understanding these relationships at a mechanistic level provides valuable insights into disease pathogenesis and reveals novel therapeutic opportunities. The dynamic and reversible nature of epigenetic modifications makes them particularly attractive targets for therapeutic intervention, with several epigenetic drugs already in clinical use and many more in development [2]. As research in this field advances, the integration of multi-omics approaches and the development of more sophisticated experimental tools will undoubtedly uncover additional layers of complexity in the regulatory networks connecting different epigenetic elements. This knowledge will enhance our ability to develop targeted epigenetic therapies for cancer and other complex diseases, ultimately paving the way for more precise and effective treatments.

This whitepaper elucidates the intricate bidirectional regulatory dialogue between microRNAs (miRNAs) and the epigenetic machinery, a critical interface in gene expression control. miRNAs, short non-coding RNA molecules, fine-tune gene expression at the post-transcriptional level and directly target effectors of DNA methylation and histone modification. Concurrently, their own expression is regulated by these same epigenetic mechanisms. This review details the molecular players in this exchange, provides standardized experimental protocols for its investigation, discusses profound therapeutic implications, and visualizes these complex relationships to serve researchers and drug development professionals advancing this frontier.

Epigenetics encompasses heritable changes in gene function that occur without alterations to the underlying DNA sequence. The major epigenetic mechanisms include DNA methylation, histone modifications, and the activity of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) [1]. These systems do not operate in isolation; they form a complex, interdependent regulatory network. MicroRNAs (miRNAs), a class of short (~22 nucleotide) non-coding RNAs, have emerged as pivotal players within this network [10].

MiRNAs function as potent regulators of gene expression by binding to target mRNAs through sequence complementarity, primarily within the 3' untranslated region (3'-UTR), leading to translational repression or mRNA degradation [11]. It is estimated that over 60% of human protein-coding genes are regulated by miRNAs, underscoring their extensive influence on the cellular transcriptome [10]. A fascinating dimension of their function is the targeting of enzymes responsible for epigenetic modifications. This places miRNAs at the heart of a sophisticated bidirectional regulatory circuit: they can be regulated by epigenetic mechanisms while simultaneously shaping the epigenetic landscape itself [12] [13]. This review dissects this dialogue, with a specific focus on how miRNAs post-transcriptionally regulate DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) and histone-modifying enzymes, and frames this interplay within the context of therapeutic development.

miRNAs as Regulators of DNA Methylation

DNA methylation, the covalent addition of a methyl group to cytosine in CpG dinucleotides, is a key epigenetic mark associated with transcriptional silencing. This process is catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), including the maintenance methyltransferase DNMT1 and the de novo methyltransferases DNMT3A and DNMT3B [1]. A subset of miRNAs, termed "epi-miRNAs," directly targets these enzymes, creating a direct link between miRNA activity and the DNA methylation landscape [13].

Key miRNA-DNMT Interactions

The following table summarizes well-characterized miRNAs that target DNA methyltransferases, along with their functional consequences.

Table 1: miRNAs Regulating DNA Methyltransferases

| miRNA | Target DNMT | Biological Role & Mechanism | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-148a | DNMT1 | Acts as a tumor suppressor; directly targets DNMT1 3'UTR, creating a negative feedback loop (miR-148a is itself silenced by DNMT1-mediated promoter hypermethylation) [14]. | Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cell lines (HepG2, SMMC-7721); overexpression inhibits proliferation [14]. |

| miR-29 family | DNMT3A, DNMT3B | Directly targets DNMT3A/B mRNAs; restoration of miR-29 can reverse hypermethylation and reactivate silenced tumor suppressor genes [12] [13]. | Lung cancer, acute myeloid leukemia (AML); acts as a tumor suppressor [13]. |

| miR-143 | DNMT3A | Targets DNMT3A; its downregulation leads to increased DNMT3A and aberrant methylation [15]. | Research in various cancers. |

| miR-26a | DNMT3B | Regulates DNMT3B expression; often dysregulated in cancer and other diseases [1]. | Multiple cancer models. |

The regulatory relationship between miR-148a and DNMT1 exemplifies a classic negative feedback loop. In hepatocellular carcinogenesis, hypermethylation of the miR-148a promoter, potentially mediated by the aberrant upregulation of DNMT1, leads to its transcriptional silencing. The subsequent loss of miR-148a relieves the repression on DNMT1, further consolidating the hypermethylated state. Restoring miR-148a expression has been shown to inhibit HCC cell proliferation, highlighting its tumor-suppressive function [14]. Beyond direct targeting, non-coding RNAs can regulate DNMTs through direct protein binding, as demonstrated by Fos ecRNA, which inhibits DNMT3A activity in neurons through a sequence-independent mechanism [15].

miRNAs as Regulators of Histone-Modifying Enzymes

Histone modifications—including acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination—constitute a "histone code" that governs chromatin structure and accessibility [13]. These covalent marks are added, removed, and interpreted by a suite of enzymes, many of which are direct targets of miRNAs.

Targeting Histone Methyltransferases and Demethylases

The Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) component Enhancer of Zeste Homolog 2 (EZH2), which catalyzes the repressive H3K27me3 mark, is a frequent target of tumor-suppressive miRNAs.

- miR-26a, miR-101, and miR-214 have been shown to directly target EZH2, and their loss in cancer leads to EZH2 overexpression, enhancing repressive chromatin states and promoting proliferation [11] [12].

- In B-cell lymphomas, the oncogenic transcription factor MYC recruits EZH2 and HDAC3 to the promoter of the miR-29 gene, repressing its transcription. This illustrates how a histone-modifying enzyme can be part of a complex that silences a regulatory miRNA [12].

Targeting Histone Deacetylases (HDACs) and Acetyltransferases

Histone deacetylases (HDACs) remove acetyl groups, leading to chromatin condensation and gene repression. Several miRNAs directly target HDACs.

- The miR-15a/16-1 cluster is epigenetically silenced by HDAC3 recruitment, often mediated by MYC, in lymphoid malignancies. Pharmacological inhibition of HDACs can reactivate these miRNAs, demonstrating the dynamic nature of this regulation [12].

- miR-449a targets HDAC1, and its expression can induce cell cycle arrest and senescence.

Table 2: miRNAs Regulating Histone-Modifying Enzymes

| Target Enzyme Class | Specific Enzyme | Regulating miRNA(s) | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Histone Methyltransferase | EZH2 | miR-26a, miR-101, miR-214, miR-98 | De-repression of EZH2 target genes; inhibition of proliferation/differentiation block [11] [12]. |

| Histone Demethylase | LSD1 | miR-137, miR-362 | Altered histone methylation landscapes. |

| Histone Deacetylase (HDAC) | HDAC1 | miR-449a, miR-200b | Increased histone acetylation, gene activation. |

| HDAC3 | miR-15a/16-1 cluster (indirect via feedback) | Regulation of apoptosis; implicated in leukemogenesis [12]. | |

| Histone Acetyltransferase | p300/CBP | miR-141 | Altered acetylation-mediated gene activation. |

Visualizing the Regulatory Network

The complex interplay between miRNAs, DNMTs, and histone-modifying enzymes can be conceptualized as a series of interconnected feedback loops. The diagram below maps these core regulatory pathways.

Diagram 1: miRNA-Epigenetic Regulatory Circuit. This map illustrates the core feedback loop where miRNAs post-transcriptionally regulate epigenetic enzymes, and these enzymes, in turn, transcriptionally regulate miRNA genes.

Experimental Protocols for Investigating miRNA-Epigenetic Interplay

To rigorously investigate the bidirectional relationship between miRNAs and epigenetic modifiers, a combination of molecular, cellular, and bioinformatic approaches is required. Below are detailed protocols for key experimental paradigms.

Protocol 1: Validating miRNA-Mediated Regulation of an Epigenetic Enzyme

Aim: To confirm that a candidate miRNA directly targets the mRNA of a specific epigenetic enzyme (e.g., DNMT1, EZH2).

Bioinformatic Prediction:

- Use databases like TargetScan, miRDB, and miRTarBase to identify putative binding sites for the miRNA in the 3'-UTR of the target gene.

Functional Validation:

- Gain-of-function: Transfert cells with synthetic miRNA mimics (e.g., 60 nM using Lipofectamine 2000) [14].

- Loss-of-function: Transfert cells with miRNA inhibitors (antagomiRs).

- Controls: Always include a non-targeting scrambled miRNA control (NS-miRNA).

Downstream Analysis:

- qRT-PCR: Quantify changes in the target mRNA level 24-48 hours post-transfection. Use kits like the miScript SYBR-Green PCR kit for miRNA quantification and standard SYBR Green for mRNA. Calculate fold-change using the 2^–ΔΔCt method with U6 snRNA and GAPDH as endogenous controls for miRNA and mRNA, respectively [14].

- Western Blotting: Assess protein level changes 48-72 hours post-transfection to confirm translational repression.

Direct Target Confirmation (Luciferase Reporter Assay):

- Clone the wild-type 3'-UTR of the target gene (containing the predicted binding site) downstream of a luciferase reporter gene (e.g., psiCHECK-2 vector).

- Generate a mutant construct with seed site mutations.

- Co-transfect each reporter construct with the miRNA mimic or control into a model cell line (e.g., HEK293T).

- Measure luciferase activity 24-48 hours later. A significant reduction in luciferase activity for the wild-type, but not the mutant, construct confirms direct binding.

Protocol 2: Assessing Epigenetic Regulation of a miRNA

Aim: To determine if a miRNA's silencing in a disease context is due to promoter hypermethylation or histone modification.

Correlative Expression & Methylation Analysis:

- Methylation-Specific PCR (MSP) or Bisulfite Sequencing:

- Treat genomic DNA with sodium bisulfite, which converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils, while methylated cytosines remain unchanged [16].

- For MSP, design primers specific for methylated and unmethylated sequences after bisulfite conversion.

- For higher resolution, perform Bisulfite Sequencing (BS-seq) or Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS) to map methylated cytosines at single-nucleotide resolution across the miRNA's promoter region [16].

- Methylation-Specific PCR (MSP) or Bisulfite Sequencing:

Functional Demethylation/De-repression:

- Treat cells with chromatin-modifying drugs:

- DNA methyltransferase inhibitor: 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine (Decitabine, 1-10 µM for 3-5 days).

- Histone deacetylase inhibitor: Trichostatin A (TSA, 0.1-1 µM for 24h).

- Perform qRT-PCR to measure miRNA expression before and after treatment. Reactivation of miRNA expression after drug treatment strongly implies epigenetic silencing [12] [13].

- Treat cells with chromatin-modifying drugs:

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assay:

- Cross-link proteins to DNA in living cells.

- Shear chromatin by sonication.

- Immunoprecipitate the cross-linked chromatin using antibodies against specific histone marks (e.g., H3K27me3 for repression, H3K4me3/H3K9ac for activation) or transcription factors.

- Reverse cross-links, purify DNA, and analyze the enrichment of the miRNA promoter region by qPCR.

The following diagram illustrates a consolidated workflow integrating these protocols.

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow. A decision-path map for designing experiments to dissect miRNA-epigenetic regulatory relationships.

Successfully navigating the experiments outlined above requires a suite of reliable reagents and tools. The following table catalogues essential resources for this field of research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for miRNA-Epigenetics Studies

| Reagent / Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Functional miRNA Modulators | miRNA Mimics (e.g., miR-148a, miR-29b); miRNA Inhibitors (AntagomiRs); Non-targeting Scrambled Controls (NS-miRNA) [14]. | Gain/loss-of-function studies to determine miRNA activity on target epigenetic enzymes. |

| Epigenetic Modulators | DNMT Inhibitors (5-azacytidine/Vidaza, decitabine/Dacogen); HDAC Inhibitors (Trichostatin A, Vorinostat) [12] [13]. | Chemical perturbation to reactivate epigenetically silenced miRNAs or genes. |

| Methylation Analysis Kits | Bisulfite Conversion Kits (e.g., EZ DNA Methylation-Lightning Kit); MSP or Pyrosequencing Kits; Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) or RRBS Services [16]. | Mapping DNA methylation status at miRNA promoters or gene regulatory regions. |

| Chromatin Analysis Kits | Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Kits with antibodies for H3K27me3, H3K4me3, H3K9ac, EZH2, etc. | Determining histone modification enrichment or transcription factor binding at specific genomic loci. |

| qRT-PCR Assays | TaqMan or SYBR Green-based miRNA Assays (e.g., miScript system); mRNA expression assays; Validated reference genes (U6, GAPDH) [14]. | Quantifying expression levels of mature miRNAs, mRNAs, and epigenetic enzymes. |

| Luciferase Reporter Vectors | psiCHECK-2, pmirGLO Vectors. | Cloning 3'-UTRs to validate direct miRNA-mRNA interactions. |

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

The reversible nature of epigenetic modifications and the ability to target miRNAs make this regulatory network a highly attractive therapeutic frontier.

- Epi-Drugs as miRNA Reactivators: FDA-approved DNA methyltransferase inhibitors (e.g., decitabine) and HDAC inhibitors can reverse the epigenetic silencing of tumor-suppressive miRNAs like miR-148a and miR-15a/16-1, providing a mechanistic basis for their anti-tumor effects [12] [13] [14].

- miRNA-Based Therapeutics: Strategies involving the restoration of tumor-suppressive miRNAs (miRNA mimics) or inhibition of oncogenic miRNAs (antagomiRs) are in preclinical and clinical development. For instance, delivering miR-29 mimics could simultaneously suppress multiple oncogenic pathways by targeting DNMT3A/B and other players [11].

- Biomarker Discovery: The stability of miRNAs in biofluids (circulating miRNAs) and the specific epigenetic silencing of miRNAs in tumors offer immense potential for developing non-invasive diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers [16] [10].

Future research must focus on untangling the cell-type and context specificity of these interactions, developing efficient and specific delivery systems for miRNA-based drugs, and integrating multi-omics data (epigenomic, transcriptomic, proteomic) to build comprehensive models of this regulatory network. The intricate dialogue between miRNAs and the epigenetic machinery is not just a biological curiosity; it is a fundamental layer of gene regulation that, when mastered, holds the key to novel therapeutic paradigms for cancer and a wide range of other human diseases.

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) have emerged as pivotal regulators of genome architecture, functioning as molecular guides that direct chromatin remodeling complexes to specific genomic loci. This whitepaper delineates the mechanisms by which lncRNAs control chromatin structure, with emphasis on their interactions with major remodeling complexes such as SWI/SNF, and places these interactions within the broader context of the epigenetic landscape involving DNA methylation and histone modifications. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these mechanisms provides a foundation for novel therapeutic strategies targeting the epigenetic machinery in cancer and other diseases. The guidance specificity of lncRNAs enables precise spatial and temporal control of gene expression programs, making them attractive targets for intervention in epigenetic dysregulation.

Long non-coding RNAs are defined as transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides with limited or no protein-coding capacity. The GENCODE database annotates over 20,000 lncRNAs in humans, though some resources estimate over 90,000 [17]. These molecules exhibit several distinctive features: they display tissue-specific expression, are frequently localized to specific subcellular compartments, and face less evolutionary selection pressure than protein-coding genes, allowing for rapid functional diversification [18] [17]. Their nuclear localization positions them ideally for roles in chromatin regulation, where they function as scaffolds, guides, or decoys to modulate chromatin structure and gene expression.

Chromatin remodeling represents a fundamental epigenetic mechanism whereby the structure of chromatin is dynamically modified to control DNA accessibility. ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes utilize energy from ATP hydrolysis to slide, evict, or restructure nucleosomes, thereby controlling transcriptional activation or repression [19]. Among these complexes, the switching defective/sucrose nonfermenting (SWI/SNF) complex stands out as a critical regulator recognized for its association with activated chromatin states and gene silencing through nucleosome positioning [19].

Molecular Mechanisms of lncRNA-Mediated Guidance

LncRNAs employ sophisticated molecular strategies to guide chromatin remodeling complexes to specific genomic addresses. The following table summarizes the primary mechanisms and key examples:

Table 1: Mechanisms of lncRNA-Mediated Guidance of Chromatin Remodeling Complexes

| Mechanism | Description | Example lncRNAs | Complex Targeted |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Binding | LncRNA directly binds subunits of remodeling complex, serving as guide or decoy | SChLAP1, UCA1, Mhrt | SWI/SNF (BAF/PBAF) |

| Recruitment Model | LncRNA recruits remodeling complex to specific genomic loci through triplex formation or other interactions | Eprn, ANRIL | SWI/SNF, PRC1/2 |

| Scaffold Function | LncRNA acts as structural scaffold to assemble multiple complex components | Xist, HOTAIR | PRC2, SWI/SNF |

| Competitive Inhibition | LncRNA sequesters remodeling factors from genomic targets | Mhrt | SWI/SNF (Brg1) |

Direct Binding and Subunit Interaction

The most direct mechanism involves specific lncRNAs physically interacting with subunits of chromatin remodeling complexes. SChLAP1 (Second Chromosome Locus Associated with Prostate 1) exemplifies this mechanism in prostate cancer, where it directly binds to the hSNF5 (SMARCB1) subunit of the SWI/SNF complex [19]. This interaction antagonizes the tumor-suppressive functions of SWI/SNF by decreasing its genomic binding, ultimately promoting cancer cell invasion and metastasis [19]. Similarly, lncRNA UCA1 binds directly to BRG1, the core ATPase subunit of SWI/SNF, interfering with its ability to bind the p21 promoter and thereby reducing p21 expression while promoting bladder cancer cell proliferation [19].

Recruitment Through Chromatin Interactions

Some lncRNAs function as recruitment modules that guide remodeling complexes to specific genomic loci. While not explicitly detailed in the search results for SWI/SNF, this mechanism is well-established for other chromatin-modifying complexes. For instance, lncRNAs can form RNA-DNA triplex structures that create docking sites for chromatin regulators [20]. The lncRNA ANRIL, which is upregulated in various cancers, participates in recruiting Polycomb repressive complexes to specific genomic loci, establishing repressive chromatin domains [21]. Although ANRIL primarily interacts with PRC1 and PRC2, this recruitment paradigm likely extends to SWI/SNF complexes through analogous mechanisms.

Scaffold and Assembly Functions

LncRNAs can serve as structural scaffolds that facilitate the assembly of multiple chromatin remodeling components. Nuclear paraspeckle assembly transcript 1 (NEAT1), a nuclear-restricted lncRNA dysregulated in various cancers, directly interacts with the SWI/SNF core units BRG1 or BRM to form paraspeckle structures that influence cell cycle progression and cancer development [19]. This scaffold function enables the coordination of multiple epigenetic regulators at specific genomic locations, creating integrated regulatory hubs that precisely control chromatin state.

Competitive Inhibition

The lncRNA Mhrt (Myheart) exemplifies a competitive inhibition mechanism, where it directly binds the Brg1 helicase domain of the SWI/SNF complex with high affinity [18]. This interaction sequesters Brg1 from genomic DNA targets, effectively inhibiting Brg1-mediated gene regulation and protecting the heart from stress-induced hypertrophy [18]. The Mhrt-Brg1 interaction showcases how lncRNAs can fine-tune chromatin remodeling activities through competitive binding to critical domains.

Interplay with DNA Methylation and Histone Modifications

The guidance of chromatin remodeling complexes by lncRNAs does not occur in isolation but is integrated within a broader epigenetic network encompassing DNA methylation and histone modifications. This integration creates multilayered regulatory circuits that enable sophisticated control of gene expression programs.

Coordination with DNA Methylation Machinery

LncRNAs directly interact with DNA methylation enzymes, creating functional crosstalk between chromatin remodeling and DNA methylation states. Numerous lncRNAs recruit DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) to specific genomic loci, establishing DNA methylation patterns that reinforce chromatin states initiated by remodeling complexes [20]. The following table summarizes key examples of lncRNAs that interface with DNA methylation machinery:

Table 2: lncRNAs Interfacing with DNA Methylation Machinery in Cancer

| lncRNA | Interaction | Target | Cancer Context | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HOTAIR | Recruits DNMT1, DNMT3B | PTEN, MTHFR, HOXA5 | CML, EC, AML | Chemoresistance, proliferation |

| TINCR | Recruits DNMT1 | miR-503-5p | Breast Cancer | Regulates EGFR expression |

| MROS-1 | Recruits DNMT3A | PRUNE2 | Ovarian Cancer | Promotes nodal metastases |

| LINC00472 | Recruits DNMTs | MCM6 | Triple-Negative BC | Inhibits tumor growth |

| H19 | Upregulates TET3 | MED12 | Uterine Leiomyoma | Promotes cell proliferation |

The lncRNA H19 demonstrates the bidirectional nature of these relationships, as it both regulates and is regulated by DNA methylation. H19 itself is controlled by promoter methylation in an imprinting-specific manner, while also upregulating TET3 to mediate active DNA demethylation at specific loci [20] [21]. This reciprocal regulation creates feedback loops that stabilize epigenetic states.

Integration with Histone Modification Systems

LncRNAs frequently bridge chromatin remodeling complexes with histone-modifying enzymes, creating coordinated epigenetic transitions. HOTAIR provides a classic example, where it serves as a scaffold that simultaneously interacts with both the SWI/SNF complex and histone-modifying complexes including PRC2 and LSD1/CoREST/REST [21] [22]. This enables synchronized histone modification (H3K27 methylation via PRC2) and chromatin remodeling (via SWI/SNF) to establish stable repressive chromatin states. Similarly, lncRNA-mediated recruitment of the BAF complex to specific genomic loci often coincides with histone acetylation changes that facilitate open chromatin configurations.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Investigating lncRNA-chromatin remodeling interactions requires multidisciplinary approaches. Below are key methodological frameworks for elucidating these relationships.

Identifying Functional lncRNA-Remodeler Interactions

RNA Immunoprecipitation (RIP) and Crosslinking-RIP (CLIP) These techniques identify direct physical interactions between lncRNAs and chromatin remodeling complex subunits. RIP utilizes antibodies against specific SWI/SNF subunits (e.g., BRG1, BRM, hSNF5) to immunoprecipitate associated RNAs from cell lysates [19]. CLIP methodologies incorporate UV crosslinking to capture transient interactions, followed by high-throughput sequencing to identify bound lncRNAs. For example, CLIP experiments demonstrated direct binding between SChLAP1 and the hSNF5 subunit of SWI/SNF in prostate cancer cells [19].

Chromatin Isolation by RNA Purification (ChIRP) ChIRP enables genome-wide mapping of lncRNA binding sites by using tiled antisense oligonucleotides to capture the lncRNA and its associated chromatin fragments [19]. This approach can reveal how specific lncRNAs guide remodeling complexes to genomic targets, as applied to demonstrate HOTAIR-mediated recruitment of PRC2 to the HOXD locus.

Functional Genomics Approaches CRISPR-based screening methods can identify functional dependencies between lncRNAs and chromatin remodelers. For instance, CRISPRi screens targeting lncRNA loci coupled with phenotypic readouts can reveal genetic interactions with SWI/SNF components [23].

Functional Validation of Guidance Mechanisms

Loss-of-Function Studies Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) and siRNA-mediated knockdown represent primary approaches for interrogating lncRNA function. ASOs, particularly those with locked nucleic acid (LNA) modifications, efficiently degrade nuclear lncRNAs and can be used to assess functional consequences on SWI/SNF localization and chromatin accessibility [24] [17].

Chromatin Accessibility Assays Assays such as ATAC-seq (Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin with high-throughput sequencing) or DNase I hypersensitivity mapping can evaluate changes in chromatin structure following lncRNA perturbation. These methods quantitatively measure how lncRNA depletion affects SWI/SNF-mediated chromatin remodeling at specific loci [19].

Nucleosome Positioning Mapping MNase-seq provides nucleotide-resolution information about nucleosome positioning and occupancy. This technique can demonstrate how lncRNA-mediated guidance of SWI/SNF complexes alters nucleosome positioning at target genes [25] [18].

Visualizing Key Mechanisms and Experimental Workflows

LncRNA Guidance of SWI/SNF Complexes

Experimental Workflow for lncRNA-Chromatin Studies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for lncRNA-Chromatin Remodeling Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibodies for IP | Anti-BRG1, Anti-BRM, Anti-BAF155, Anti-hSNF5 | RIP, ChIP | Validate specificity for IP applications |

| Oligonucleotides | LNA GapmeRs, Antisense Oligos | lncRNA knockdown | Optimize for nuclear retention targets |

| CRISPR Systems | CRISPRi/a, Cas9 nickase | lncRNA perturbation | Distinguish transcriptional vs locus effects |

| Chromatin Assays | ATAC-seq kits, MNase | Chromatin accessibility | Cell number requirements and quality controls |

| Detection Probes | RNA-FISH probes, ChIRP oligos | Spatial localization and mapping | Specificity and signal-to-noise optimization |

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

The precise guidance mechanisms employed by lncRNAs present unique therapeutic opportunities, particularly in oncology where epigenetic dysregulation is a hallmark. Several strategies are emerging:

Oligonucleotide-Based Therapeutics Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) can target oncogenic lncRNAs that misdirect chromatin remodeling complexes. For instance, targeting SChLAP1 in prostate cancer could restore proper SWI/SNF localization and function [19] [21]. Chemical modifications such as 2'-O-methyl, 2'-fluoro, and locked nucleic acid (LNA) enhance stability and cellular uptake of these oligonucleotides [24].

Small Molecule Inhibitors Small molecules that disrupt specific lncRNA-protein interactions represent an alternative approach. While challenging, high-throughput screening methods are identifying compounds that block functional interfaces between lncRNAs and chromatin remodelers [23] [17].

CRISPR-Based Interventions CRISPR-Cas systems can be engineered to target lncRNA genomic loci or manipulate their expression. CRISPR inhibition (CRISPRi) can repress oncogenic lncRNAs, while CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) can enhance tumor-suppressive lncRNAs [23].

The development of lncRNA-targeted therapeutics faces challenges including delivery efficiency, tissue specificity, and potential off-target effects. However, the tissue-specific expression patterns of many lncRNAs provide advantages for selective targeting [21] [17]. As understanding of lncRNA structural domains and interaction interfaces deepens, more sophisticated targeting strategies will emerge, potentially enabling precise correction of epigenetic dysregulation in cancer and other diseases.

LncRNAs serve as architectural guides that direct chromatin remodeling complexes to specific genomic loci, forming an essential layer of epigenetic regulation integrated with DNA methylation and histone modification systems. Through mechanisms ranging from direct binding to competitive inhibition, lncRNAs including SChLAP1, UCA1, Mhrt, and others provide spatial and temporal specificity to SWI/SNF-mediated chromatin remodeling. The experimental toolkit for investigating these relationships continues to expand, enabling increasingly precise mapping of these functional interactions. For drug development professionals, lncRNAs represent promising therapeutic targets whose manipulation may enable restoration of normal epigenetic regulation in disease states, particularly cancer. As research advances, lncRNA-guided chromatin remodeling is poised to become a cornerstone of epigenetic therapy development.

Circular RNAs (circRNAs), characterized by their covalently closed loop structure, have emerged as pivotal regulators of gene expression through their ability to sequester microRNAs (miRNAs) and RNA-binding proteins (RBPs). This regulatory capacity positions them as key modulators of the cellular epigenetic landscape. This whitepaper delineates the mechanisms by which circRNAs influence DNA methylation and histone modification, thereby controlling transcriptional programs in health and disease. We provide a comprehensive technical guide detailing the molecular mechanisms, quantitative interactions, and experimental methodologies for investigating circRNA-mediated epigenetic regulation. Designed for researchers and drug development professionals, this document integrates current research findings with practical protocols to advance the study of circRNAs in epigenetic networks.

Circular RNAs are a class of non-coding RNAs characterized by their continuous loop structure, formed through a process known as back-splicing where a downstream 5' splice site joins an upstream 3' splice site [26] [27]. This unique configuration confers exceptional stability, making circRNAs resistant to exonuclease-mediated degradation and thus ideal for long-term regulatory functions within the cell [27]. Initially considered splicing artifacts, circRNAs are now recognized as ubiquitous regulatory molecules with expression patterns that are often tissue-specific and evolutionarily conserved [26].

The functional repertoire of circRNAs is remarkably diverse. They primarily operate through two well-established mechanisms: (1) acting as competitive endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) by sequestering miRNAs and preventing them from repressing their target mRNAs, and (2) interacting with RBPs to modulate protein function, stability, or localization [26] [27]. Beyond these roles, emerging evidence places circRNAs at the center of epigenetic regulation. They participate in a complex cross-talk with major epigenetic mechanisms—DNA methylation and histone modifications—either by regulating the expression of epigenetic modifiers or by directly recruiting chromatin-modifying complexes to specific genomic loci [28] [29] [30]. This capacity to bridge the RNA world with the epigenetic machinery enables circRNAs to enact stable changes in gene expression patterns, influencing critical processes from embryonic development to oncogenesis [31] [32].

Molecular Mechanisms of circRNA Function

miRNA Sequestration (The Sponge Effect)

The most extensively characterized function of circRNAs is their role as miRNA sponges. This mechanism involves circRNAs containing multiple binding sites for specific miRNAs, effectively sequestering them and preventing their interaction with target mRNAs [26] [33]. The core of this effect lies in the formation of stable RNA-miRNA complexes through complementary base pairing, which leads to the derepression of miRNA-targeted genes [26].

A paradigmatic example is CDR1as (ciRS-7), which contains over 70 conserved binding sites for miR-7 [26]. By sponging miR-7, CDR1as regulates the expression of miR-7 target genes, such as the oncogene EGFR, thereby influencing cellular processes like proliferation and apoptosis [26]. Similarly, circHIPK3 has been shown to sponge multiple miRNAs, including miR-124, thereby modulating the expression of genes involved in cell cycle regulation and tumorigenesis [26]. The efficiency of a circRNA as a miRNA sponge is influenced by the number and affinity of its miRNA-binding sites, its abundance, and its subcellular localization [26].

Table 1: Well-Characterized circRNAs with miRNA Sponging Activity

| circRNA | Sponged miRNA(s) | Biological Context | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| CDR1as (ciRS-7) | miR-7 | Cancer, Neurological disorders | Derepression of EGFR and other miR-7 targets |

| circHIPK3 | miR-124, others | Multiple cancers (e.g., lung, liver) | Modulation of cell proliferation and tumor growth |

| circSMARCA5 | Not specified in results | Cancer | Regulation of tumor progression [26] |

| circ-406742 | miR-1200 | Alcohol Dependence (NAc brain region) | Regulation of HRAS, PRKCB, HOMER1, PCLO genes [34] |

Protein Sequestration and Scaffolding

Beyond miRNA sponging, circRNAs interact with a wide array of proteins, functioning as scaffolds, decoys, or recruiters [27]. These interactions can alter protein function, facilitate the formation of multi-protein complexes, or modulate the localization of RBPs [26] [27].

For instance, circRNAs can stabilize proteins by protecting them from degradation, as demonstrated by the interaction between HuR and circPABPN1, which enhances the stability of circPABPN1 [26]. Conversely, circRNAs can act as protein decoys; CDR1as can interact with the tumor suppressor p53, potentially blocking its interaction with the negative regulator MDM2 [27]. The RBP Quaking (QKI) not only promotes the biogenesis of circRNAs like circSMARCA5 but also facilitates its nuclear retention, which is crucial for its role in regulating gene expression [26]. The pleiotropic nature of circRNA-protein interactions underscores their significant potential to influence diverse cellular pathways, including those governing epigenetic states.

Table 2: Examples of circRNA-Protein Interactions and Functional Consequences

| circRNA | Interacting Protein | Type of Interaction | Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| circPABPN1 | HuR | Stabilization | Enhanced circRNA stability [26] |

| CDR1as | p53, IGF2BP3 | Decoy, Functional modulation | Blocks p53-MDM2; compromises IGF2BP3 pro-metastatic function [27] |

| circSMARCA5 | Quaking (QKI) | Biogenesis & Localization | Promotes nuclear retention of circRNA [26] |

| circFBXW7 | Not specified | Functional Association | Linked to expression of epigenetic regulators and transcription factors in AML [29] |

Direct Modulation of Epigenetic Machinery

The interplay between circRNAs and the epigenetic landscape is a rapidly advancing field. circRNAs can influence epigenetic marks in two primary ways: by regulating the expression of epigenetic writers, erasers, and readers, or by directly recruiting chromatin-modifying complexes.

Regulating Epigenetic Enzyme Expression: Many circRNAs impact epigenetic processes indirectly by sponging miRNAs that target transcripts of epigenetic enzymes. For example, the circRNA_101237 landscape is associated with the expression of key epigenetic regulators like DNMT1 and EZH2 [29]. EZH2 is the catalytic subunit of the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2), which deposits the repressive H3K27me3 mark, while DNMT1 is crucial for maintaining DNA methylation patterns [31].

Direct Recruitment and Interaction: Some nuclear-retained circRNAs can directly interact with chromatin-modifying complexes. Although the search results do not provide a specific human circRNA example for direct recruitment, they indicate that intron-containing circRNAs (EIciRNAs) can promote the transcription of their host genes through interactions with the U1 snRNP [35], illustrating a direct nuclear mechanism. Furthermore, a general mechanism exists where circRNAs can recruit proteins to chromatin, influencing transcription [27].

The diagram below illustrates the core mechanisms by which circRNAs sequester biomolecules and influence the epigenetic landscape.

Quantitative Analysis of circRNA-mRNA Regulatory Axes in Cancer

To illustrate the concrete impact of circRNA-mediated sequestration, the following table summarizes key regulatory triads (circRNA-miRNA-mRNA) identified through bioinformatic analyses of cancer data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and other sources [33]. These triads represent networks where a circRNA, by sponging a miRNA, indirectly regulates the expression of a target mRNA. The correlation between circRNA and mRNA expression serves as indirect evidence for the functional activity of the sponge mechanism.

Table 3: Experimentally Inferred circRNA-miRNA-mRNA Regulatory Triads in Cancers

| Cancer Type | circRNA | Sponged miRNA | Target mRNA | mRNA Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (HNSCC) | hsacirc0036186 (PKM2) | Not specified | 14-3-3-ζ | Cancer-associated gene [33] |

| HNSCC | hsacirc0001387 (WHSC1) | miR-942 | SFRP4 | Driver gene [33] |

| HNSCC | hsacirc0001821 (circPVT1) | miR-942 | SFRP4 | Driver gene [33] |

| Lung Cancer | hsacirc0051620 (SLC1A5) | miR-338-3p | ADAM17, CDH2, RUNX2, ZBTB18 | Driver genes [33] |

| Lung Cancer | hsacirc0066954 (POLQ) | miR-338-3p | ADAM17, CDH2, RUNX2, ZBTB18 | Driver genes [33] |

| Bladder Cancer | circHIPK3 | miR-558 | HPSE (Heparanase) | Experimentally validated axis [29] |

Methodologies for Investigating circRNA-Epigenetic Interactions

Studying the role of circRNAs in epigenetics requires a multi-faceted approach, combining standard molecular biology techniques with specialized tools designed for circular transcripts.

Core Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validating circRNA-miRNA Interactions

This protocol outlines the key steps for experimentally confirming that a circRNA directly binds to a specific miRNA. This is crucial for establishing its role as a sponge that can indirectly influence epigenetic regulators.

- In Silico Prediction: Utilize databases like CircInteractome [29] or CSCD [29] to predict potential miRNA response elements (MREs) on the candidate circRNA.

- Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay:

- Cloning: Clone the sequence of the circRNA, or more specifically its junction region containing the predicted MREs, downstream of a luciferase reporter gene (e.g., psiCHECK-2 vector).

- Site-Directed Mutagenesis: Generate a mutant construct where the seed sequence of the MRE is disrupted.

- Transfection: Co-transfect the reporter construct (wild-type or mutant) along with the miRNA mimic (or a negative control) into cultured cells.

- Measurement: After 24-48 hours, measure firefly and Renilla luciferase activities. A significant decrease in luciferase activity in the wild-type group co-transfected with the miRNA mimic, but not in the mutant group, confirms direct binding [26] [33].

- RNA Immunoprecipitation (RIP) with Ago2 Antibodies: Immunoprecipitate Argonaute 2 (Ago2), the core component of the RISC complex, from cell lysates. Detect the co-precipitation of both the circRNA and the miRNA of interest using RT-qPCR, providing evidence that they reside in the same functional complex [27].

- Functional Rescue: Transfert cells with a circRNA overexpression vector and observe derepression of a known target of the miRNA (e.g., an epigenetic enzyme like EZH2 or DNMT1). This effect should be abolished by concurrent overexpression of the miRNA [33].

Protocol 2: Analyzing circRNA-Protein Interactions for Epigenetic Studies

This protocol is used to identify and validate proteins, including epigenetic regulators, that interact with a circRNA.

- RNA Pull-Down / RNA Affinity Purification:

- Bait Design: Synthesize biotin-labeled DNA or RNA oligonucleotides that are complementary to the circRNA's back-splice junction, ensuring specificity over linear transcripts.

- Pull-Down: Incubate the labeled probes with streptavidin-coated magnetic beads. Then, incubate this complex with whole-cell lysates to allow proteins to bind the immobilized circRNA.

- Analysis: Wash the beads stringently, elute the bound proteins, and identify them using Mass Spectrometry (MS) or detect specific candidates via Western Blotting [27].

- RIP (RNA Immunoprecipitation): The reverse of the above. Use an antibody against a specific protein (e.g., an epigenetic writer like EZH2 or a reader) to pull it down from a cell lysate. Then, detect the associated circRNA using RT-qPCR or RNA-seq. This confirms an in vivo interaction [27].

- Localization Analysis (FISH/IF Co-staining): Perform Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) to detect the circRNA and Immunofluorescence (IF) to detect the protein of interest (e.g., DNMT1) in the same cell. Colocalization, particularly in the nucleus, supports a functional interaction relevant to epigenetic regulation [27].

Protocol 3: Assessing Functional Impact on DNA Methylation

This protocol determines if a circRNA influences DNA methylation patterns, a direct readout of epigenetic change.

- Genetic Manipulation: Create stable cell lines with knockdown or knockout of the circRNA using CRISPR/Cas9 or siRNA strategies targeting the back-splice junction, or overexpress the circRNA.

- Genome-Wide Analysis (Bisulfite Sequencing): Extract genomic DNA from manipulated and control cells. Treat DNA with bisulfite, which converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils but leaves methylated cytosines unchanged. Subsequent sequencing (e.g., Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing) allows for the mapping of methylated cytosines at single-base resolution genome-wide [31].

- Locus-Specific Analysis (Methylation-Specific PCR): For candidate genes, design primers that distinguish between methylated and unmethylated DNA after bisulfite treatment. This provides a rapid, quantitative assessment of methylation status at specific promoter regions of interest (e.g., tumor suppressor genes) [28].

- Integration with Transcriptome Data: Correlate changes in DNA methylation with changes in gene expression profiles (from RNA-seq) in the same samples to link the circRNA-induced epigenetic alteration to transcriptional outcomes [29].

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for circRNA-Epigenetic Studies

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| RNase R | Enzymatic treatment of RNA samples to degrade linear RNAs (mRNAs, rRNAs, tRNAs) and enrich for circRNAs. | Critical step for validating circularity and improving detection in RT-qPCR and RNA-seq [35]. |

| Divergent Primers | Primer pairs designed with their 3' ends facing away from each other, specifically amplifying the unique back-splice junction of a circRNA in PCR. | Essential for specific detection and quantification of circRNAs, avoiding amplification of linear isoforms [35]. |

| Biotin-labeled Junction Probes | DNA or RNA oligonucleotides complementary to the back-splice junction, used for RNA pull-down assays. | Enables specific isolation of the circRNA and its interacting proteins from complex cellular lysates [27]. |

| Anti-Ago2 Antibodies | Used in RIP assays to immunoprecipitate the miRNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). | Confirms the presence of a circRNA within a functional miRNA complex, supporting the sponge mechanism [27]. |

| CircIMPACT (R Package) | Bioinformatics tool that integrates circRNA and gene expression data to identify genes and pathways whose expression correlates with circRNA abundance. | Helps prioritize circRNAs for functional study and infers potential downstream effects, including on epigenetic pathways [29]. |

CircRNAs have firmly established themselves as stable modulators within the cellular regulatory hierarchy, with a profound capacity to influence epigenetic landscapes through the sequestration of miRNAs and proteins. Their interaction with key epigenetic machineries, such as DNMTs, TET enzymes, and PRC2, provides a mechanistic link between RNA biology and stable, heritable gene expression states. This interplay is critically implicated in human diseases, most notably in cancer, where circRNAs can regulate the expression of oncogenes and tumor suppressors via epigenetic remodeling.

The translational potential of circRNAs is immense. Their inherent stability, tissue-specific expression, and central regulatory roles make them attractive candidates as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers [26] [32]. Furthermore, they represent novel therapeutic targets; strategies could include using antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) to knock down pathogenic circRNAs or developing methods to overexpress tumor-suppressive circRNAs [32] [35]. The ongoing development of bioinformatics tools like CircIMPACT will continue to empower researchers to decipher complex circRNA-centric networks [29].

Future research must focus on elucidating the precise structural determinants of circRNA-protein interactions, particularly with chromatin modifiers. The development of more sophisticated in vivo models to study the systemic impact of circRNA modulation, and the continued innovation in delivery systems for circRNA-based therapeutics, will be crucial to harnessing the full potential of these fascinating stable modulators in medicine.

The regulatory interplay between epigenetic marks and non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) represents a fundamental layer of transcriptional control in health and disease. This technical guide examines the reciprocal relationship wherein DNA methylation and histone modifications govern the expression of ncRNA genes, while ncRNAs, particularly long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), simultaneously direct the establishment of these epigenetic marks. We synthesize current mechanistic insights demonstrating that this bidirectional crosstalk forms sophisticated feedback loops that fine-tune gene expression programs in development, cellular differentiation, and pathogenesis. The document provides detailed experimental methodologies for investigating these relationships and presents key reagent solutions to support epigenetic research, offering researchers a comprehensive framework for advancing studies in epigenetic regulation.

Epigenetics encompasses heritable changes in gene expression that do not alter the underlying DNA sequence, primarily mediated through DNA methylation, histone modifications, and regulatory non-coding RNAs [36] [37]. Once considered merely passive transcriptional products, ncRNAs are now recognized as potent epigenetic regulators that interact with DNA methylation and histone modification machinery in a complex, reciprocal relationship [38] [2]. This bidirectional crosstalk creates precise regulatory circuits that control gene expression at chromosomal, transcriptional, and post-transcriptional levels.

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), defined as transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides without protein-coding capacity, serve as central players in these regulatory networks [39]. They function as guides, tethers, decoys, and scaffolds to direct epigenetic modifier complexes to specific genomic loci, enabling targeted gene activation or silencing [40]. Simultaneously, the expression of lncRNA genes themselves is controlled by the epigenetic landscape of their promoter and enhancer regions, creating sophisticated feedback and feedforward loops that maintain cellular homeostasis or drive disease progression when dysregulated [38].

Understanding these reciprocal mechanisms provides critical insights into normal development and disease pathogenesis, particularly in cancer, where aberrant epigenetic-ncRNA circuits contribute to unchecked proliferation, metastasis, and therapeutic resistance [38] [2]. This guide examines the molecular underpinnings of this regulatory reciprocity and provides technical resources for its experimental investigation.

DNA Methylation in the Control of Non-Coding RNA Genes

Mechanistic Basis of DNA Methylation

DNA methylation involves the covalent addition of a methyl group to the 5' position of cytosine bases, primarily within cytosine-phosphate-guanine (CpG) dinucleotides [38] [41]. This modification is catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), with DNMT3A and DNMT3B performing de novo methylation, and DNMT1 maintaining methylation patterns during DNA replication [38] [37]. The methyl group donor for these reactions is S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) [38]. DNA methylation typically leads to transcriptional repression when present in gene promoter regions by physically impeding transcription factor binding or recruiting proteins that promote chromatin condensation [37] [41].

Table 1: DNA Methylation Machinery Components

| Component | Type | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| DNMT1 | Enzyme (Maintenance methyltransferase) | Maintains DNA methylation patterns during DNA replication |

| DNMT3A, DNMT3B | Enzyme (De novo methyltransferases) | Establish new DNA methylation patterns on unmethylated DNA |

| TET enzymes (TET1/2/3) | Enzyme (Demethylases) | Initiate DNA demethylation through oxidation of 5mC to 5hmC |

| MBD proteins | Reader | Recognize and bind methylated CpG sites |

| S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) | Cofactor | Methyl group donor for methylation reactions |

DNA Methylation Directly Regulates ncRNA Expression

The expression of ncRNA genes is directly controlled by the DNA methylation status of their regulatory regions. Promoter hypermethylation typically silences tumor suppressor lncRNAs in cancer, while hypomethylation can activate oncogenic lncRNAs [38]. This regulatory mechanism represents a fundamental pathway through which epigenetic marks control the ncRNA transcriptome.

Research in breast cancer demonstrates that genome-wide methylation patterns significantly correlate with corresponding lncRNA expression profiles, suggesting DNA methylation serves as a primary regulator of lncRNA transcription [38]. The methylation status of DNA can affect lncRNA expression levels, and conversely, lncRNAs can regulate DNA methylation, demonstrating true reciprocity in their relationship [38].

Experimental Evidence and Methodologies

Investigation of DNA methylation-mediated ncRNA regulation employs several well-established techniques:

Bisulfite Sequencing: Treatment of DNA with bisulfite converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils, while methylated cytosines remain unchanged, allowing for single-base resolution mapping of methylation patterns. For studying lncRNA promoter methylation, genomic DNA is isolated, treated with bisulfite, and the regulatory regions of interest are amplified and sequenced [42].

Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS): This comprehensive approach assesses methylation status across the entire genome, enabling identification of differentially methylated regions associated with ncRNA expression [42]. The protocol involves: (1) Fragmenting genomic DNA and preparing sequencing libraries; (2) Treating libraries with bisulfite; (3) High-throughput sequencing; (4) Aligning sequences to a reference genome and calculating methylation ratios for each cytosine.

DNA Immunoprecipitation (DIP): Utilizes antibodies specific to 5-methylcytosine (5mC) or its oxidized forms to immunoprecipitate methylated DNA fragments, which can then be quantified by qPCR or sequenced [42]. For ncRNA studies, DIP can validate methylation in specific lncRNA promoter regions.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflows for DNA methylation analysis comparing bisulfite sequencing and immunoprecipitation approaches.

Histone Modifications as Regulators of ncRNA Transcription

Histone Modification Machinery

Histone modifications constitute a complex epigenetic code that governs chromatin accessibility and gene expression. These post-translational modifications—including methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination—occur primarily on the N-terminal tails of histone proteins [39] [37]. The combinatorial nature of these modifications forms a "histone code" that can be read by specialized protein complexes to determine transcriptional outcomes [37].

Table 2: Key Histone Modifications and Their Functional Consequences

| Modification | Associated Function | Histone Variant | Effector Complexes |

|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 | Transcriptional activation | H3 | COMPASS-like, MLL1 |

| H3K27me3 | Transcriptional repression | H3 | PRC2 (EZH2) |

| H3K9me3 | Heterochromatin formation | H3 | HP1 |

| H3K36me3 | Transcriptional elongation | H3 | - |

| H3K9ac | Transcriptional activation | H3 | - |

| H4K16ac | Chromatin decondensation | H4 | - |

Histone modifications are dynamically regulated by opposing enzyme activities: writers (histone methyltransferases HMTs, histone acetyltransferases HATs) add modifications, erasers (histone demethylases KDMs, histone deacetylases HDACs) remove them, and readers (proteins with specialized domains like bromodomains and chromodomains) interpret the modifications [40] [42].

Histone Modification-Directed Control of ncRNA Expression

The chromatin landscape established by histone modifications directly controls ncRNA gene expression by determining the accessibility of transcriptional machinery. Facultative heterochromatin marked by H3K27me3 is particularly relevant for lncRNA regulation, as many developmental lncRNAs are positioned within genomic regions enriched for this repressive mark [39].

A well-characterized example involves the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2), which catalyzes H3K27 trimethylation. PRC2 is recruited to specific genomic loci by numerous lncRNAs, but the expression of these lncRNAs is itself regulated by the histone modification status at their gene loci [39] [40]. This creates a self-regulatory loop where lncRNAs both influence and are influenced by the histone modification landscape.

Plant Models of Histone-ncRNA Regulation

Studies in Arabidopsis thaliana provide elegant examples of histone modification control of lncRNA expression. During vernalization, the lncRNA COLD ASSISTED INTRONIC NONCODING RNA (COLDAIR) is transcribed from the first intron of FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC) and recruits PRC2 to establish H3K27me3-mediated silencing of FLC [39]. However, COLDAIR expression itself is induced by cold exposure through changes in histone modifications at its promoter, including increased H3K4me3 and decreased H3K27me3 [39].

Similarly, the lncRNA MAS regulates flowering time in Arabidopsis by recruiting the COMPASS-like complex to deposit H3K4me3 at the MAF4 locus, activating its expression [39]. The expression of MAS is cold-induced and regulated by histone modifications, demonstrating how environmental signals can be integrated into gene regulatory networks through histone modification-directed lncRNA expression.

Reciprocal Control: Non-Coding RNAs as Epigenetic Regulators

LncRNAs as Guides for Epigenetic Machinery

LncRNAs function as central epigenetic regulators through their ability to recruit chromatin-modifying complexes to specific genomic loci. They achieve this through their modular structure, which often includes protein-binding domains that interact with epigenetic complexes and DNA-binding domains that provide target specificity through complementary base pairing [39] [40].

The PRC2 complex represents the best-characterized example of lncRNA-directed epigenetic regulation. Multiple lncRNAs, including Xist, HOTAIR, and ANRIL, interact with PRC2 through their specific structural motifs and guide it to target genes where it establishes repressive H3K27me3 marks [39] [40]. Similarly, lncRNAs can recruit activating complexes; the lncRNA ST3Gal6-AS1 binds histone methyltransferase MLL1 and recruits it to the promoter region of ST3Gal6, inducing H3K4me3 modification and transcriptional activation [39].

LncRNA Regulation of DNA Methylation

LncRNAs directly influence DNA methylation patterns through multiple mechanisms. Some lncRNAs interact with DNA methyltransferases to regulate their activity or targeting. For example, the antisense CEBPA RNA functions as a mixed inhibitor of DNMT1, while antisense E-cadherin RNA inhibits DNMT3A activity [15].

Recent research has revealed that Fos extra-coding RNA (ecRNA) directly inhibits DNMT3A activity in neurons, leading to hypomethylation of the Fos gene and contributing to long-term fear memory formation [15]. Structural analyses indicate that Fos ecRNA binds the DNMT3A tetramer interface, inhibiting its methylation activity without requiring sequence specificity or DNA-RNA complex formation [15].

Integrated Regulatory Circuitry

The reciprocity between epigenetic marks and ncRNAs creates integrated regulatory circuits that can amplify or fine-tune transcriptional responses. These circuits often form positive or negative feedback loops that stabilize cellular states during differentiation or in response to environmental cues.

In cancer, these reciprocal relationships frequently become dysregulated, contributing to malignant transformation. For instance, the lncRNA FEZF1-AS1 is overexpressed in gastric cancer and recruits lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD1) to the promoter of p21, removing activating H3K4me2 marks and repressing p21 expression [39]. The expression of FEZF1-AS1 itself is regulated by promoter methylation and histone modifications, creating a self-reinforcing oncogenic circuit.

Diagram 2: Reciprocal regulatory circuitry between epigenetic marks and lncRNAs, demonstrating feedback loops that can stabilize transcriptional states.

Experimental Approaches for Investigating Epigenetic-ncRNA Relationships

Chromatin Analysis Techniques

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) enables the identification of histone modifications or transcription factors associated with specific genomic regions, including ncRNA promoters. The standard protocol involves: (1) Cross-linking proteins to DNA with formaldehyde; (2) Chromatin fragmentation by sonication or enzymatic digestion; (3) Immunoprecipitation with antibodies specific to the histone modification or protein of interest; (4) Reversal of cross-links and DNA purification; (5) Analysis by qPCR (ChIP-qPCR) or sequencing (ChIP-seq) [42].

Chromatin Isolation by RNA Purification (ChIRP) represents a specialized technique to map the genomic binding sites of specific lncRNAs. In this method: (1) Cells are cross-linked with formaldehyde; (2) Chromatin is fragmented and incubated with biotinylated antisense oligonucleotides complementary to the target lncRNA; (3) RNA-DNA complexes are pulled down using streptavidin beads; (4) Associated DNA is purified and identified by sequencing [39].

Integrated Multi-Omics Approaches

Comprehensive understanding of epigenetic-ncRNA reciprocity requires integration of multiple data types. Genome-wide association of lncRNAs with epigenetic marks can be investigated through simultaneous analysis of: (1) LncRNA expression profiles (RNA-seq); (2) DNA methylation patterns (WGBS or reduced representation bisulfite sequencing); (3) Histone modification maps (ChIP-seq for multiple marks); (4) Chromatin accessibility (ATAC-seq) [43].

Studies in Brassica rapa demonstrate the power of this integrated approach, revealing associations between lncRNAs and inverted repeat regions, 24-nt small interfering RNAs, DNA methylation, and H3K27me3 marks [43]. Such multi-epigenomic analyses provide comprehensive views of the regulatory landscape controlling and controlled by ncRNA expression.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Epigenetic-ncRNA Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Methylation Antibodies | Anti-5-methylcytosine (5mC), Anti-5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) | DIP, Immunofluorescence, ELISA | Detection and quantification of DNA methylation marks |

| Histone Modification Antibodies | Anti-H3K4me3, Anti-H3K27me3, Anti-H3K9ac | ChIP, Western Blot, Immunofluorescence | Specific detection of histone activation/repression marks |

| Chromatin Remodeling Complex Antibodies | Anti-EZH2 (PRC2), Anti-SUZ12, Anti-EED | ChIP, RIP, Western Blot | Identification of epigenetic complex components |

| DNMT Inhibitors | 5-azacytidine, Decitabine | Functional studies | Demethylation of DNA to test methylation-dependent effects |

| HDAC Inhibitors | Trichostatin A, Vorinostat | Functional studies | Increased histone acetylation to test acetylation-dependent effects |

| RNA Immunoprecipitation Kits | EZ-Magna RIP, ChIRP Kit | RIP, ChIRP | Identification of proteins bound to specific RNAs or genomic loci bound by specific RNAs |

The reciprocal regulation between DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNA genes represents a fundamental layer of epigenetic control that integrates environmental signals with gene expression programs. This bidirectional crosstalk creates sophisticated regulatory circuits that maintain cellular identity, guide development, and when disrupted, contribute to disease pathogenesis.

Future research in this field will likely focus on developing more precise tools for mapping and manipulating these relationships in vivo, including CRISPR-based epigenetic editing systems coupled with ncRNA targeting approaches. Additionally, understanding the three-dimensional chromatin architecture context of these interactions and their dynamics in single cells will provide unprecedented resolution of epigenetic-ncRNA regulatory networks.

The therapeutic potential of targeting these reciprocal relationships is substantial, particularly in cancer, where aberrant epigenetic-ncRNA circuits drive malignant progression. Small molecules targeting epigenetic enzymes, combined with oligonucleotide-based approaches targeting regulatory ncRNAs, represent promising therapeutic strategies that may eventually enable precise reprogramming of dysregulated gene expression patterns in disease.

As research methodologies continue to advance, particularly in single-cell multi-omics and spatial transcriptomics, our understanding of the intricate reciprocity between epigenetic marks and ncRNAs will deepen, revealing new insights into both normal physiology and disease mechanisms and opening novel avenues for therapeutic intervention.

From Bench to Bedside: Analytical Techniques and Therapeutic Targeting of the Epigenetic Triad

The integration of Epigenome-Wide Association Studies (EWAS) with non-coding RNA (ncRNA) transcriptomics represents a transformative approach for unraveling complex gene regulatory networks in development, disease, and therapeutic intervention. This technical guide provides a comprehensive framework for designing and implementing integrated epigenetic-ncRNA studies, detailing experimental methodologies, computational pipelines, and analytical considerations. By simultaneously mapping DNA methylation, histone modifications, and diverse ncRNA species, researchers can achieve unprecedented insights into the multilayered regulation of genome function and identify novel biomarkers for drug development.