Revolutionizing Heart Research

How Stem Cells Are Unlocking the Secrets of Congenital Heart Disease

The future of understanding our hearts lies not only in clinics but also in petri dishes.

The Global Challenge of CHD

births involve congenital heart defects

Congenital Heart Disease (CHD) is the most common birth defect in the world, affecting approximately 1 in 100 newborns globally 1 5 . For decades, understanding the intricate dance of genetic and environmental factors that lead to these devastating conditions has been a formidable challenge for scientists. The quest has been hindered by the inability to observe a developing human heart firsthand and the limitations of animal models, which often fail to fully replicate human disease 4 6 .

A revolutionary technology is now transforming the landscape of cardiac research: pluripotent stem cells. These powerful cells, capable of becoming any cell type in the body, are allowing scientists to grow human heart cells in a lab, creating personalized "diseases-in-a-dish" that are illuminating the hidden origins of CHD and paving the way for new treatments 1 2 .

The Blueprint: What Are Pluripotent Stem Cells?

To appreciate the breakthrough, one must first understand the tool. Pluripotent stem cells are the master cells of the body. They are "unprogrammed" cells with two extraordinary abilities: they can divide and create more of themselves indefinitely, and they can differentiate into any of the over 200 specialized cell types that make up a human being, from brain neurons to beating heart cells 2 4 .

Types of Pluripotent Stem Cells

- Human Embryonic Stem Cells (hESCs): Derived from early-stage embryos, these cells are naturally pluripotent 2 7 .

- Human-Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (hiPSCs): In a Nobel Prize-winning discovery, scientist Shinya Yamanaka found that ordinary adult skin or blood cells can be "reprogrammed" back into an embryonic-like state using "Yamanaka factors" (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) 2 6 .

The iPSC Revolution

The creation of hiPSCs was a game-changer. It meant that researchers could take a small skin sample from a patient with a genetic heart condition and create a limitless supply of that patient's own heart cells in the lab, carrying the very genetic blueprint of their disease 4 6 . This provides a unique window into studying how CHD manifests on a cellular level.

A Disease in a Dish: Modeling CHD with Stem Cells

So, how do you turn a stem cell in a dish into a tool for understanding disease? The process mimics the natural stages of early human heart development 2 .

Scientists guide pluripotent stem cells through a carefully choreographed series of steps, using specific chemical signals to steer them first into cardiac progenitor cells—the heart's building blocks—and then into fully functional, beating cardiomyocytes (heart muscle cells), as well as the endothelial cells that line blood vessels and the smooth muscle cells that support them 2 3 7 .

This approach allows researchers to model a wide array of congenital heart conditions. For instance, hiPSCs have been created from patients with Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome (HLHS), a severe defect where the left side of the heart is critically underdeveloped 2 5 . These patient-derived heart cells have revealed key abnormalities, such as reduced expression of genes vital for heart cell proliferation and maturation 5 . Similarly, models of Williams-Beuren Syndrome, which causes supravalvar aortic stenosis, have shown how a missing elastin gene leads to dysfunctional vascular smooth muscle cells that proliferate excessively and cause narrowings in major arteries 2 .

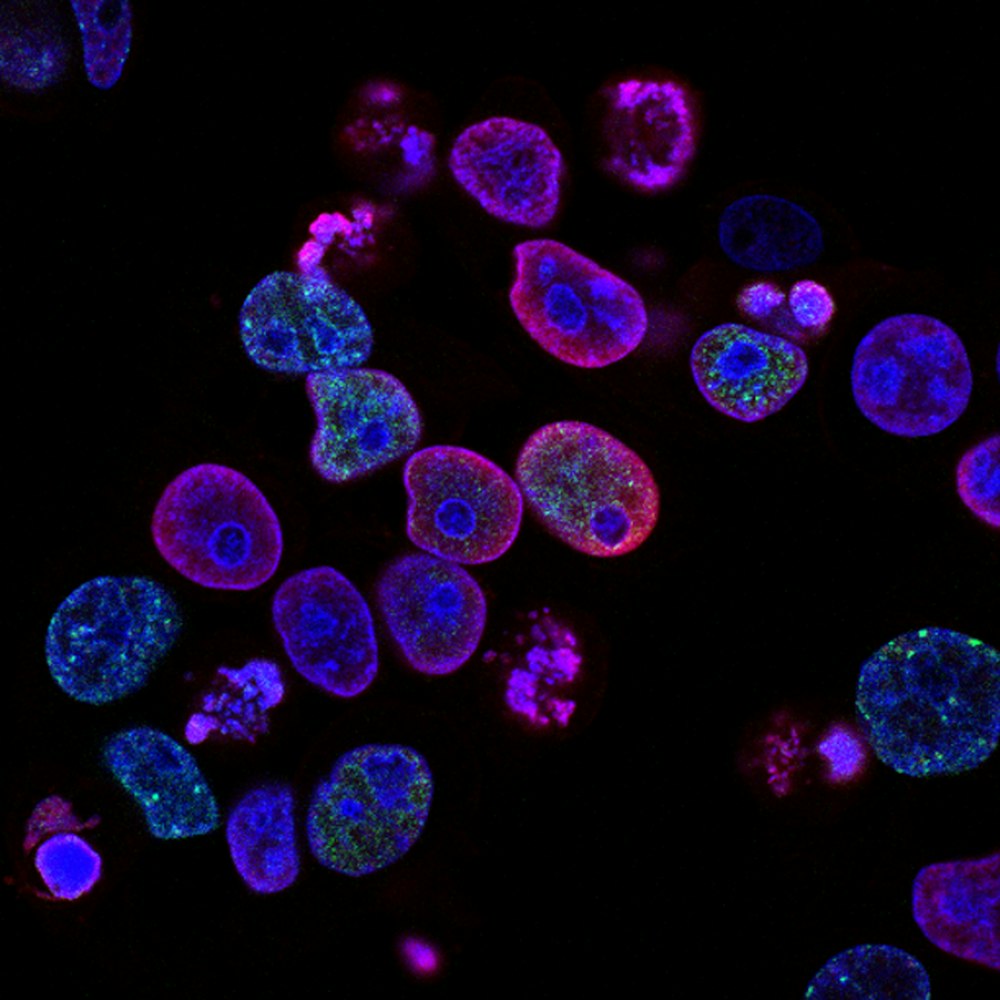

Stem cell differentiation in a laboratory setting allows researchers to create patient-specific heart cells for disease modeling.

Congenital Heart Diseases Modeled Using Patient-Specific iPSCs

| CHD Subtype | Key Affected Gene(s) | Observed Cellular Phenotype in iPSC Models |

|---|---|---|

| Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome (HLHS) | NOTCH1, others 6 | Impaired cardiomyocyte growth, reduced contractility, aberrant signaling pathways 2 5 |

| Williams-Beuren Syndrome | ELN (Elastin) 2 | Vascular smooth muscle cell over-proliferation, poor contractile function 2 |

| Long QT Syndrome (LQTS) | KCNQ1, KCNH2, SCNSA 4 | Prolonged action potential duration, irregular electrical activity, arrhythmias 4 |

| Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) | BICC1, MYH11 6 | Altered gene expression in collagen and muscle pathways 6 |

A Deep Dive into a Key Experiment: Unraveling HLHS

One of the most compelling examples of this technology in action is a series of experiments aimed at understanding the mechanisms behind HLHS. Researchers began by studying heart tissue from HLHS fetuses and discovered a troubling signature of cellular stress: evidence of chronic hypoxia (low oxygen) and DNA damage, which triggered cellular senescence—a state in which cells can no longer divide and function properly 2 .

To prove that hypoxia itself could cause these changes, the team designed a critical experiment using human embryonic stem cell-derived heart cells 2 .

The Methodology: Step-by-Step

Differentiation

Researchers guided hESCs to become the three main cell types of the heart: cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells, and vascular smooth muscle cells 2 .

Hypoxic Exposure

These immature heart cells were then placed in a special chamber that maintained a low-oxygen environment (1% oxygen) for 72 hours, simulating the suspected conditions in the HLHS heart 2 .

Phenotype Analysis

The cells were meticulously analyzed and compared to heart cells grown under normal oxygen conditions.

Therapeutic Intervention

Finally, the researchers tested whether a drug that inhibits a key protein called TGFβ1 could reverse the damage caused by hypoxia 2 .

Results and Analysis: Connecting the Dots

The results were striking. The lab-grown heart cells exposed to low oxygen recapitulated the HLHS phenotype perfectly 2 . They showed:

- A marked increase in HIF1α (the master regulator of hypoxia)

- Evidence of DNA damage and cellular senescence

- A significant reduction in the number of cardiomyocytes and endothelial cells

- Decreased contractile function

- Increased activity of TGFβ1, a protein linked to fibrosis (scarring) 2

Most importantly, when the cells were treated with a TGFβ1 inhibitor, the damaging effects were partially reversed. The abnormal phenotype was rescued, suggesting that targeting this pathway could be a viable therapeutic strategy to promote heart growth and reduce scarring in HLHS patients, potentially before they are even born 2 .

This experiment brilliantly demonstrates the power of stem cell models: it moved from an observation in human patients, to establishing a cause-and-effect relationship in the lab, and finally to identifying a potential treatment—all within a controlled human-relevant system.

Functional Differences Observed in iPSC-Derived Heart Cells

| Functional Metric | Healthy iPSC-Derived Cardiomyocytes | Diseased iPSC-Derived Cardiomyocytes (e.g., HLHS, LQTS) |

|---|---|---|

| Contractility | Strong, rhythmic, and synchronized beating 3 | Weaker, irregular, or unsynchronized contraction 2 5 |

| Electrical Activity | Normal action potential duration; no arrhythmias 4 | Prolonged action potential; early after-depolarizations (EADs); arrhythmias under stress 4 |

| Calcium Handling | Normal, rhythmic calcium transients 4 | Dysregulated calcium cycling; increased diastolic calcium; irregular transients 4 |

| Proliferation & Maturation | Normal progression to a more mature state 3 | Impaired growth, often arrested in a more immature, fetal-like state 2 5 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Technologies Supercharging Discovery

The basic model of growing heart cells in a dish has been supercharged by several advanced technologies, creating a sophisticated toolkit for discovery.

Cardiac Organoids

Scientists can now coax stem cells to self-organize into three-dimensional "cardiac organoids"—miniature, simplified versions of the heart. These tiny structures more closely mimic the architecture and cellular interactions of the real organ, providing a more realistic environment to study complex defects 6 .

Gene Editing with CRISPR/Cas9

This technology acts as a "molecular scissors," allowing researchers to correct a disease-causing mutation in a patient's iPSCs or, conversely, to introduce a specific mutation into healthy cells. This helps confirm whether a genetic variant is truly responsible for the observed disease traits 6 .

Single-Cell Analysis

Instead of analyzing a whole mass of cells together, scientists can now examine the genetic profile of individual cells. This has revealed tremendous diversity among heart cells and helped pinpoint exactly which cell types are most affected by a CHD-causing mutation 6 .

Key Research Reagents for Stem Cell-Based Disease Modeling

| Research Tool | Function in CHD Modeling |

|---|---|

| Yamanaka Factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) | Reprograms adult somatic cells (e.g., skin fibroblasts) into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) 2 6 |

| Growth Factors (Activin A, BMP4) | Directs the differentiation of pluripotent stem cells into cardiac mesoderm, the precursor of heart cells 7 |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing | Allows precise correction of disease-causing mutations in patient iPSCs or introduction of mutations into healthy cells to confirm their role 6 |

| TGFβ1 Inhibitor | A chemical used in experiments to block a fibrosis-related pathway, helping to validate therapeutic targets 2 |

| Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq) | Reveals the heterogeneity of iPSC-derived heart cells and identifies distinct gene expression patterns in diseased vs. healthy cells 6 |

The Future: From the Lab Bench to the Clinic

The journey of pluripotent stem cells in CHD research is far from over. The ultimate goals are as ambitious as they are transformative.

Personalized Medicine

A doctor could one day test which drug works best for a specific patient's condition using their own cells in a lab, before ever prescribing it 6 .

Early-stage clinical trials, such as the ELPIS trial, are already exploring the safety of injecting stem cells into the hearts of infants with HLHS to improve their heart function 5 .

While challenges remain—such as ensuring the complete maturity and safety of lab-grown cells—the progress is undeniable 3 6 7 . The ability to hold a beating cluster of human heart cells that carry a specific disease under a microscope has fundamentally changed our approach to congenital heart disease. It has brought us closer than ever to answering the fundamental question of "why?" and is equipping us with the tools to finally do something about it.

The future of CHD treatment lies at the intersection of stem cell technology, genomics, and personalized medicine.