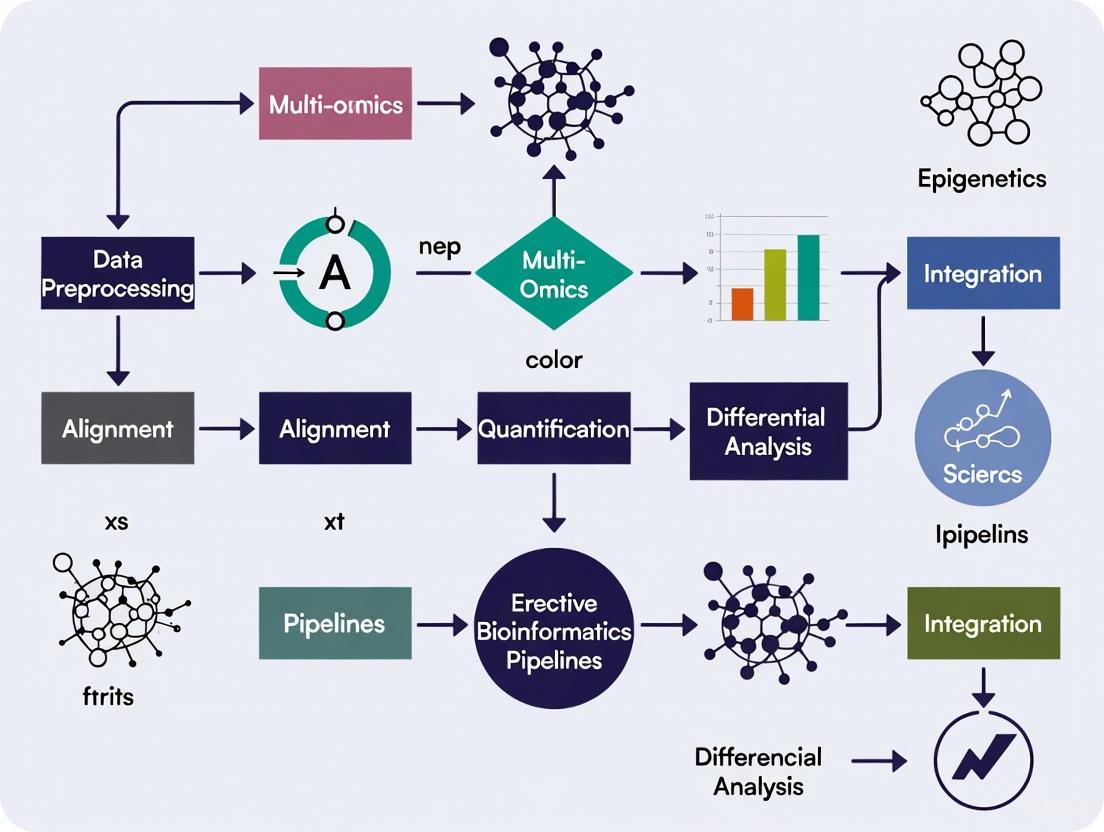

Integrative Bioinformatics Pipelines for Multi-Omics Epigenetics Data: From Foundational Concepts to Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on integrative bioinformatics pipelines for multi-omics epigenetics data.

Integrative Bioinformatics Pipelines for Multi-Omics Epigenetics Data: From Foundational Concepts to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on integrative bioinformatics pipelines for multi-omics epigenetics data. It explores the foundational principles of epigenetics—covering DNA methylation, histone modifications, and chromatin accessibility—and details the essential experimental assays and databases. The scope extends to a thorough examination of methodological approaches for data integration, including network-based analysis, multiple kernel learning, and deep learning architectures. The article further addresses critical challenges in data processing, computational scalability, and model interpretability, offering practical optimization strategies. Finally, it covers validation frameworks, performance benchmarking, and the translation of integrative models into clinical applications for precision medicine, biomarker discovery, and therapeutic development.

Demystifying the Epigenetic Landscape: Core Concepts and Data Sources for Multi-Omics Integration

Epigenetic regulation involves heritable and reversible changes in gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence, serving as a crucial interface between genetic inheritance and environmental influences [1]. The three primary epigenetic mechanisms—DNA methylation, histone modifications, and chromatin remodeling—act synergistically to control cellular processes including proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis [1]. In the context of integrative bioinformatics pipelines, understanding these mechanisms provides a foundational framework for multi-omics epigenetics research, enabling researchers to connect molecular observations across genomic, transcriptomic, epigenomic, and proteomic datasets.

Dysregulation of epigenetic controls contributes significantly to disease pathogenesis, with particular relevance for male infertility where spermatogenesis failure results from epigenetic and genetic dysregulation [1]. The precise regulation of spermatogenesis relies on synergistic interactions between genetic and epigenetic factors, underscoring the importance of epigenetic regulation in male germ cell development [1]. Recent advancements in multi-omics technologies have unveiled molecular mechanisms of epigenetic regulation in spermatogenesis, revealing how deficiencies in enzymes such as PRMT5 can increase repressive histone marks and alter chromatin states, leading to developmental defects [1].

DNA Methylation: Mechanisms and Analytical Approaches

Molecular Basis and Enzymatic Machinery

DNA methylation involves the covalent addition of a methyl group to the 5th carbon of cytosines within CpG dinucleotides, forming 5-methylcytosine (5mC) [1]. This process is catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) using S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) as the methyl donor [1]. In mammalian genomes, 70-90% of CpG sites are typically methylated under normal physiological conditions, while CpG islands—genomic regions with high G+C content (>50%) and dense CpG clustering—remain largely unmethylated and are frequently located near promoter regions or transcriptional start sites [1].

The distribution and dynamics of DNA methylation are precisely controlled by writers (DNMTs), erasers (demethylases), and readers (methyl-binding proteins) as detailed in Table 1. DNMT1 functions primarily as a maintenance methyltransferase, ensuring fidelity of methylation patterns during DNA replication by methylating hemimethylated CpG sites on nascent DNA strands [1]. In contrast, DNMT3A and DNMT3B act as de novo methyltransferases that establish new methylation patterns during early embryogenesis and gametogenesis [1]. DNMT3L, though catalytically inactive, serves as a cofactor that enhances the enzymatic activity of DNMT3A/B [1]. The recently discovered DNMT3C plays a specialized role in spermatogenesis, with deficiencies causing severe defects in double-strand break repair and homologous chromosome synapsis during meiosis [1].

Table 1: DNA Methylation Enzymes and Their Functions

| Category | Enzyme/Protein | Function | Consequences of Loss-of-Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Writers | DNMT1 | Maintenance methyltransferase | Apoptosis of germline stem cells; Hypogonadism and meiotic arrest [1] |

| DNMT3A | De novo methyltransferase | Abnormal spermatogonial function [1] | |

| DNMT3B | De novo methyltransferase | Fertility with no distinctive phenotype [1] | |

| DNMT3C | De novo methyltransferase | Severe defect in DSB repair and homologous chromosome synapsis during meiosis [1] | |

| DNMT3L | DNMT cofactor (catalytically inactive) | Decrease in quiescent spermatogonial stem cells [1] | |

| Erasers | TET1 | DNA demethylation | Fertile [1] |

| TET2 | DNA demethylation | Fertile [1] | |

| TET3 | DNA demethylation | Information not specified [1] | |

| Readers | MBD1-4, MeCP2 | Methylated DNA binding proteins | Recruit complexes containing histone deacetylases [1] |

DNA Methylation Dynamics During Spermatogenesis

DNA methylation plays pivotal roles in germ cell development, with its dynamics tightly regulated during embryonic and postnatal stages [1]. Mouse primordial germ cells (mPGCs), the precursor cells of spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs), undergo genome-wide DNA demethylation as they migrate to the gonads between embryonic days 8.5 (E8.5) and 13.5 (E13.5) [1]. During this period, 5mC levels in mPGCs decrease to approximately 16.3%, significantly lower than the 75% 5mC abundance in embryonic stem cells [1]. This hypomethylation is driven by repression of de novo methyltransferases DNMT3A/B and elevated activity of DNA demethylation factors such as TET1, leading to erasure of methylation at transposable elements and imprinted loci [1]. Subsequently, from E13.5 to E16.5, de novo DNA methylation is gradually reestablished and maintained until birth [1].

This DNA methylation state is evolutionarily conserved between mice and humans [1]. Human primordial germ cells (hPGCs) undergo global demethylation during gonadal colonization, reaching minimal DNA methylation by week 10-11 with completion of sex differentiation [1]. Throughout spermatogenesis, DNA methylation patterns differ significantly between male germ cell types. Differentiating spermatogonia (c-Kit+ cells) exhibit higher levels of DNMT3A and DNMT3B compared to undifferentiated spermatogonia (Thy1+ cells, enriched for SSCs), suggesting that DNA methylation regulates the SSCs-to-differentiating spermatogonia transition [1]. Genome-wide DNA methylation increases during this transition, while DNA demethylation occurs in preleptotene spermatocytes [1]. DNA methylation gradually rises through leptotene and zygotene stages, reaching high levels in pachytene spermatocytes [1].

Protocol: Bisulfite Sequencing for DNA Methylation Analysis

Principle: Bisulfite conversion treatment deaminates unmethylated cytosines to uracils (read as thymines in sequencing), while methylated cytosines remain unchanged, allowing for single-base resolution mapping of methylation status.

Reagents and Equipment:

- Sodium bisulfite solution

- DNA purification columns or magnetic beads

- High-fidelity DNA polymerase for bisulfite-converted DNA

- Next-generation sequencing platform

- Bioinformatics tools for bisulfite sequence alignment (e.g., Bismark, BS-Seeker)

Procedure:

- DNA Extraction and Quality Control: Isolate high-quality genomic DNA from testicular biopsies or germ cells. Assess DNA integrity using agarose gel electrophoresis or Bioanalyzer.

- Bisulfite Conversion: Treat 500ng-1μg genomic DNA with sodium bisulfite using commercial kits. Perform conversion under optimized conditions (typically 16-20 hours at 50°C).

- Purification: Desalt and purify bisulfite-converted DNA using provided columns or magnetic beads.

- Library Preparation: Amplify converted DNA using bisulfite-specific primers. Construct sequencing libraries with appropriate adapters.

- Sequencing: Perform next-generation sequencing on Illumina platforms (e.g., NovaSeq X Series, NextSeq 1000/2000) to achieve >10x coverage of the target genome [2].

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Trim adapter sequences and quality filter reads.

- Align bisulfite-treated reads to reference genome using specialized aligners.

- Extract methylation calls and calculate methylation percentages for each cytosine.

- Perform differential methylation analysis between sample groups (e.g., OA vs NOA patients).

Quality Control:

- Include control DNA with known methylation patterns

- Monitor conversion efficiency (>99% conversion of unmethylated cytosines)

- Assess sequencing quality metrics (Q-score >30 for >80% of bases)

Histone Modifications: Complexity and Computational Mapping

Histone Modification Types and Functional Consequences

Histone modifications represent post-translational chemical changes to histone proteins that reversibly alter chromatin structure and function, ultimately influencing gene expression [1] [3]. These modifications include phosphorylation, ubiquitination, methylation, and acetylation, which can either promote or inhibit gene expression depending on the specific modification site and cellular context [1]. Histone modifications serve as crucial epigenetic marks that regulate access to DNA by transcription factors and RNA polymerase, thereby controlling transcriptional initiation and elongation.

Different histone modifications establish specific chromatin states that either facilitate or repress gene expression. For instance, trimethylation of histone H3 at lysine 4 (H3K4me3) is associated with recombination sites and active transcription, while trimethylation of histone H3 at lysine 27 (H3K27me3) and trimethylation of histone H3 at lysine 9 (H3K9me3) are associated with depleted recombination sites and transcriptional repression [3]. Super-resolution microscopy studies have revealed distinct structural patterns of these modifications along pachytene chromosomes during meiosis: H3K4me3 extends outward in loop structures from the synaptonemal complex, H3K27me3 forms periodic clusters along the complex, and H3K9me3 associates primarily with the centromeric region at chromosome ends [3].

Protocol: Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing (ChIP-seq)

Principle: Antibodies specific to histone modifications are used to immunoprecipitate cross-linked DNA-protein complexes, followed by sequencing to map genome-wide modification patterns.

Reagents and Equipment:

- Antibodies against specific histone modifications (e.g., anti-H3K4me3, anti-H3K27me3)

- Protein A/G magnetic beads

- Formaldehyde for cross-linking

- Sonication device (e.g., Bioruptor, Covaris)

- Library preparation kit for NGS

- Next-generation sequencing platform

Procedure:

- Cross-linking: Treat cells with 1% formaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature to cross-link proteins to DNA.

- Cell Lysis and Chromatin Shearing: Lyse cells and isolate nuclei. Shear chromatin to 200-500 bp fragments using sonication.

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate chromatin with specific histone modification antibody overnight at 4°C. Add Protein A/G magnetic beads and incubate for 2 hours. Wash beads extensively to remove non-specific binding.

- Cross-link Reversal and DNA Purification: Reverse cross-links by heating at 65°C overnight. Treat with Proteinase K and RNase A. Purify immunoprecipitated DNA using columns or magnetic beads.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Prepare sequencing libraries using Illumina library prep kits [2]. Sequence on appropriate platform (e.g., NovaSeq X Series for high throughput).

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Quality control of raw sequencing data (FastQC).

- Alignment to reference genome (Bowtie2, BWA).

- Peak calling to identify enriched regions (MACS2).

- Differential binding analysis between conditions (DiffBind).

- Integration with transcriptomic data to correlate modification patterns with gene expression.

Quality Control:

- Include input DNA control (non-immunoprecipitated)

- Assess antibody specificity using positive and negative control regions

- Monitor sequencing library complexity

- Verify reproducibility between biological replicates

Chromatin Remodeling Complexes: Architectural Regulation

Mechanisms of Chromatin Remodeling

Chromatin remodeling complexes (CRCs) are multi-protein machines that alter nucleosome positioning and composition using ATP hydrolysis, thereby regulating DNA accessibility [1]. These complexes control critical cellular processes including cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis, with their dysfunction linked to various diseases [1]. During spermatogenesis, chromatin remodeling undergoes a dramatic transformation where histones are progressively replaced by protamines to achieve extreme nuclear compaction in mature spermatids, a process essential for proper sperm function [1].

CRCs function through several mechanistic approaches: (1) sliding nucleosomes along DNA to expose or occlude regulatory elements, (2) evicting histones to create nucleosome-free regions, (3) exchanging canonical histones for histone variants that alter chromatin properties, and (4) altering nucleosome structure to facilitate transcription factor binding. The precise coordination of these remodeling activities ensures proper chromatin architecture throughout spermatogenesis, with defects leading to spermatogenic failure and male infertility [1].

Advanced Visualization Techniques for Chromatin Architecture

Advanced microscopy approaches enable direct visualization of chromatin structure and remodeling dynamics. Fluorescence lifetime imaging coupled with Förster resonance energy transfer (FLIM-FRET) can probe chromatin condensation states by measuring distance-dependent energy transfer between fluorophores, with higher FRET efficiency indicating more condensed heterochromatin [3]. This technique has been applied to measure DNA compaction, gene activity, and chromatin changes in response to stimuli such as double-stranded breaks or drug treatments [3].

Electron microscopy (EM) with immunolabeling provides ultrastructural localization of epigenetic marks in relation to chromatin architecture. For example, EM studies using anti-5mC antibodies with gold-conjugated secondary antibodies have revealed unexpected distribution patterns of DNA methylation, with higher abundance at the edge of heterochromatin rather than concentrated near the nuclear envelope as previously assumed [3]. This challenges conventional understanding of 5mC function and suggests potential accessibility limitations in current labeling techniques.

Super-resolution microscopy (SRM) techniques, particularly single-molecule localization microscopy (SMLM), have enabled nanoscale visualization of histone modifications and chromatin organization. This approach has revealed the structural distribution of histone modifications during meiotic recombination, providing insights into how specific modifications like H3K27me3 form periodic, symmetrical patterns on either side of the synaptonemal complex, potentially supporting its structural integrity [3].

Integrative Multi-Omics Pipelines for Epigenetic Research

Data Integration Strategies

Integrating multiple omics datasets is essential for comprehensive understanding of complex epigenetic regulatory systems [4]. Multi-omics data integration can be classified into horizontal (within-omics) and vertical (cross-omics) approaches [5]. Horizontal integration combines datasets from a single omics type across multiple batches, technologies, and laboratories, while vertical integration combines diverse datasets from multiple omics types from the same set of samples [5]. Effective integration strategies must account for varying numbers of features, statistical properties, and intrinsic technological limitations across different omics modalities.

Three primary methodological approaches for multi-omics integration include:

- Combined Omics Integration: Explains phenomena within each omics type in an integrated manner, generating independent datasets.

- Correlation-Based Strategies: Applies correlations between generated omics data and creates data structures such as networks to represent relationships.

- Machine Learning Integrative Approaches: Utilizes one or more types of omics data to comprehensively understand responses at classification and regression levels [4].

The Quartet Project has pioneered ratio-based profiling using common reference materials to address irreproducibility in multi-omics measurement and data integration [5]. This approach scales absolute feature values of study samples relative to those of a concurrently measured common reference sample, producing reproducible and comparable data suitable for integration across batches, labs, platforms, and omics types [5].

Protocol: Multi-Omics Integration Using Ratio-Based Profiling

Principle: Using common reference materials to convert absolute feature measurements into ratios enables more reproducible integration across omics datasets by minimizing technical variability.

Reagents and Equipment:

- Quartet multi-omics reference materials (DNA, RNA, protein, metabolites) [5]

- Appropriate omics measurement platforms (NGS, LC-MS/MS)

- Bioinformatics tools for ratio calculation and integration

Procedure:

- Reference Material Selection: Select appropriate multi-omics reference materials such as the Quartet suite, which includes references derived from B-lymphoblastoid cell lines of a family quartet (parents and monozygotic twin daughters) [5].

- Sample Processing: Process study samples and reference materials concurrently using the same experimental batches and conditions.

- Multi-Omics Data Generation:

- Generate genomic data using DNA sequencing platforms

- Profile DNA methylation using bisulfite sequencing or arrays

- Analyze transcriptome using RNA-seq platforms

- Quantify proteins using LC-MS/MS-based proteomics

- Measure metabolites using LC-MS/MS-based metabolomics [5]

- Ratio Calculation: For each feature, calculate ratios by scaling absolute values of study samples relative to those of the common reference sample: Ratiosample = Valuesample / Value_reference.

- Data Integration:

- Perform horizontal integration of datasets from the same omics type using the ratio-based data

- Conduct vertical integration across different omics types using correlation-based approaches or network analysis

- Apply machine learning algorithms for pattern recognition and biomarker identification

- Biological Validation: Validate integrated findings using orthogonal methods and functional assays.

Quality Control Metrics:

- Mendelian concordance rate for genomic variant calls

- Signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) for quantitative omics profiling

- Sample classification accuracy (ability to distinguish related individuals)

- Central dogma consistency (correlation between DNA variants, RNA expression, and protein abundance) [5]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Epigenetic Studies

| Category | Product/Resource | Specific Example | Application and Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Materials | Quartet Multi-omics Reference Materials | DNA, RNA, protein, metabolites from family quartet [5] | Provides ground truth for quality control and data integration across omics layers |

| DNA Methylation | Bisulfite Conversion Kits | EZ DNA Methylation kits | Convert unmethylated cytosines to uracils while preserving methylated cytosines |

| Methylation-specific Antibodies | Anti-5-methylcytosine | Immunodetection of methylated DNA in various applications | |

| Histone Modifications | Modification-specific Antibodies | Anti-H3K4me3, Anti-H3K27me3, Anti-H3K9me3 [3] | Chromatin immunoprecipitation and immunodetection of specific histone marks |

| Histone Modification Reader Domains | HMRD-based sensors [3] | Detection and visualization of histone modifications in living cells | |

| Chromatin Visualization | Super-resolution Microscopy | SMLM, STORM, STED | High-resolution imaging of chromatin organization and epigenetic marks |

| FLIM-FRET Systems | Fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopes | Measure chromatin compaction and molecular interactions in live cells | |

| Sequencing Platforms | Production-scale Sequencers | NovaSeq X Series [2] | High-throughput multi-omics data generation |

| Benchtop Sequencers | NextSeq 1000/2000 [2] | Moderate-throughput sequencing for individual labs | |

| Data Analysis | Multi-omics Analysis Software | Illumina Connected Multiomics, Partek Flow [2] | Integrated analysis and visualization of multi-omics datasets |

| Correlation Analysis Tools | Correlation Engine [2] | Biological context analysis by comparing data with curated public multi-omics data |

The integrative analysis of DNA methylation, histone modifications, and chromatin remodeling complexes provides unprecedented insights into the epigenetic regulation of spermatogenesis and its implications for male infertility. Current evidence highlights the dynamic nature of these epigenetic mechanisms throughout germ cell development, with precise temporal control essential for normal spermatogenesis [1]. Dysregulation at any level can disrupt the delicate balance of self-renewal and differentiation in spermatogonial stem cells, leading to spermatogenic failure.

Future research directions should focus on several key areas. First, the application of single-cell multi-omics technologies will enable resolution of epigenetic heterogeneity within testicular cell populations, providing deeper understanding of cell fate decisions during spermatogenesis. Second, the development of more sophisticated bioinformatics tools for multi-omics data integration will facilitate identification of master epigenetic regulators that could serve as therapeutic targets. Third, advanced epigenome editing techniques based on CRISPR systems offer promising approaches for precise epigenetic modulation to correct dysfunction [6]. Finally, the implementation of standardized reference materials and ratio-based quantification methods will enhance reproducibility and comparability across multi-omics studies [5].

The continued advancement of integrative bioinformatics pipelines for multi-omics epigenetics research holds tremendous potential for unraveling the complex etiology of male infertility and developing novel diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic strategies. By connecting molecular observations across multiple biological layers, researchers can move toward a comprehensive understanding of how epigenetic mechanisms orchestrate normal spermatogenesis and how their dysregulation contributes to reproductive pathology.

Epigenomic assays are powerful tools for deciphering the regulatory code beyond the DNA sequence, providing critical insights into gene expression dynamics in health and disease. In the context of integrative bioinformatics pipelines for multi-omics research, these technologies enable the layered analysis of DNA methylation, chromatin accessibility, histone modifications, and transcription factor binding. The convergence of data from these disparate assays, facilitated by advanced systems bioinformatics, allows for the reconstruction of comprehensive regulatory networks and a deeper understanding of complex biological systems [7]. This application note details the key experimental protocols and quantitative parameters for essential epigenomic assays, providing a foundation for their integration in multi-omics studies.

Core Epigenomic Assays: Methodologies and Applications

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing (ChIP-seq)

Purpose: Identifies genome-wide binding sites for transcription factors and histone modifications via antibody-mediated enrichment [8].

Detailed Protocol:

- Cross-linking: Treat cells with formaldehyde (typically 1%) to cross-link proteins to DNA.

- Chromatin Fragmentation: Sonicate or use micrococcal nuclease to shear cross-linked chromatin into 200–600 bp fragments.

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate chromatin with a target-specific antibody. Protein A/G beads are used to capture the antibody-bound complexes.

- Cross-link Reversal & Purification: Reverse cross-links by heating (e.g., 65°C overnight), then purify the enriched DNA fragments.

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Construct sequencing libraries from the immunoprecipitated DNA using kits such as the KAPA HyperPrep Kit, which is optimized for low-input samples and reduces amplification bias [8].

Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin using Sequencing (ATAC-seq)

Purpose: Maps regions of open chromatin to identify active promoters, enhancers, and other cis-regulatory elements [8].

Detailed Protocol:

- Cell Lysis: Isolate nuclei from cells using a mild detergent.

- Tagmentation: Incubate nuclei with the Tn5 transposase, which simultaneously fragments accessible DNA and inserts sequencing adapters.

- DNA Purification: Purify the tagmented DNA.

- Library Amplification: Amplify the purified DNA using a high-fidelity polymerase like KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix for uniform coverage [8]. The protocol can be performed with as few as 50,000 cells [8].

Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS)

Purpose: Provides a single-nucleotide resolution map of DNA methylation across the entire genome [9] [8].

Detailed Protocol:

- Library Preparation: Fragment genomic DNA and convert it into a sequencing library.

- Bisulfite Conversion: Treat the library with sodium bisulfite, which deaminates unmethylated cytosines to uracils, while methylated cytosines remain unchanged [9] [8].

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the converted DNA using a uracil-tolerant polymerase, such as KAPA HiFi Uracil+ HotStart DNA Polymerase, to prevent bias [8].

- Sequencing & Analysis: Sequence the amplified library and align reads to a reference genome, quantifying methylation at each cytosine position.

Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS)

Purpose: A cost-effective method that enriches for CpG-rich regions of the genome (like CpG islands and gene promoters) for methylation analysis [9] [8].

Detailed Protocol:

- Restriction Digestion: Digest genomic DNA with the methylation-insensitive restriction enzyme MspI (cuts CCGG sites).

- Size Selection: Isalate digested fragments in a specific size range (e.g., 40-220 bp) via gel electrophoresis or magnetic beads, enriching for CpG-dense regions.

- Bisulfite Conversion & Sequencing: Perform bisulfite conversion and library preparation as in WGBS [9].

Diagram 1: ATAC-seq workflow involves tagmentation of open chromatin and library amplification.

Diagram 2: WGBS and RRBS workflows both rely on bisulfite conversion but differ in initial steps.

Comparative Analysis of Epigenomic Assays

The following tables summarize the key technical specifications and applications of the core epigenomic assays, providing a guide for appropriate experimental selection.

Table 1: Technical Specifications and Data Output of Core Epigenomic Assays

| Assay | Biological Target | Resolution | Input DNA | Coverage/Throughput | Primary Data Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChIP-seq [8] | Protein-DNA interactions (TFs, Histones) | ~200 bp (enriched regions) | 1 ng - 1 µg | Genome-wide for antibody target | Peak files (BED), signal tracks (WIG/BigWig) |

| ATAC-seq [8] | Chromatin Accessibility | Single-nucleotide (for footprinting) | 50,000+ nuclei | Genome-wide | Peak files (BED), insertion tracks |

| WGBS [9] [8] | DNA Methylation (5mC) | Single-nucleotide | 10 ng - 1 µg | Entire genome | Methylation ratios per cytosine |

| RRBS [9] | DNA Methylation (5mC) | Single-nucleotide | 10 ng - 100 ng | ~1-5% of genome (CpG-rich regions) | Methylation ratios per cytosine in enriched regions |

Table 2: Application Strengths and Considerations for Assay Selection

| Assay | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChIP-seq | High specificity for target protein; direct measurement of binding | Dependent on antibody quality/availability; requires cross-linking | Mapping histone marks, transcription factor binding sites, chromatin states |

| ATAC-seq | Fast protocol; low cell input; maps open chromatin genome-wide | Does not directly identify bound proteins | Identifying active regulatory elements, nucleosome positioning, chromatin dynamics |

| WGBS | Gold standard; comprehensive single-base methylation map | Higher cost and sequencing depth required; DNA degradation from bisulfite [9] | Discovery of novel methylation patterns; integrative multi-omics |

| RRBS | Cost-effective; focuses on functionally relevant CpG-rich regions | Limited to a subset of the genome; may miss regulatory elements outside CpG islands [9] | Methylation profiling in large cohorts; biomarker discovery |

Integrated and Multi-Omics Approaches

A pivotal advancement in epigenomics is the development of multi-omics integration techniques, which combine two or more layers of information from the same sample.

- EpiMethylTag: This method simultaneously examines chromatin accessibility (M-ATAC) or transcription factor binding (M-ChIP) alongside DNA methylation on the same DNA molecules. It uses a Tn5 transposase loaded with methylated adapters, followed by bisulfite conversion, requiring lower input DNA and sequencing depth than performing assays separately [10].

- AI-Driven Integration: Machine learning and artificial intelligence models are increasingly used to integrate disparate epigenomic datasets. These approaches can predict disease markers, gene expression, and chromatin states from epigenomic data, enhancing the discovery power of multi-omics studies [11].

- Systems Bioinformatics: In the framework of integrative bioinformatics, data from ChIP-seq, ATAC-seq, and bisulfite sequencing are layered with transcriptomic and proteomic data. This systems-level approach is crucial for reconstructing comprehensive biological networks and understanding complex diseases like cancer and neurodegenerative disorders [7] [12].

Diagram 3: Multi-omics integration combines data from various epigenomic assays for a systems-level view.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful epigenomic analysis relies on specialized reagents and kits optimized for these complex assays.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Epigenomic Assays

| Reagent / Kit | Primary Function | Key Feature | Compatible Assays |

|---|---|---|---|

| KAPA HyperPrep Kit [8] | Library preparation | High yield of adapter-ligated library; low amplification bias | ChIP-seq, Methyl-seq (pre-conversion) |

| KAPA HiFi Uracil+ HotStart DNA Polymerase [8] | Amplification of bisulfite-converted DNA | Tolerance to uracil residues in DNA template | WGBS, RRBS |

| KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix [8] | PCR amplification for library construction | Improved sequence coverage; reduced bias | ATAC-seq, ChIP-seq |

| Methylated Adapters for Tn5 [10] | Tagmentation with integrated bisulfite capability | Adapters contain methylated cytosines | M-ATAC, M-ChIP (EpiMethylTag) |

| Tn5 Transposase | Simultaneous DNA fragmentation and adapter ligation | Enables tagmentation-based assays | ATAC-seq, EpiMethylTag |

The arsenal of epigenomic assays, including ChIP-seq, ATAC-seq, WGBS, and RRBS, provides researchers with a powerful means to decode the regulatory landscape of the genome. The choice of assay depends on the biological question, with considerations for resolution, coverage, and input requirements. The future of epigenomic research lies in the intelligent integration of these datasets using multi-omics platforms and sophisticated bioinformatics pipelines. Techniques like EpiMethylTag that capture multiple layers of information simultaneously, combined with AI-driven analysis, are pushing the frontiers of systems biology. This will ultimately accelerate biomarker discovery, therapeutic development, and our fundamental understanding of disease mechanisms in the era of precision medicine [7] [12].

The advancement of precision medicine relies on the integrated analysis of vast, complex biological datasets. Key to this progress are large-scale public data repositories that provide standardized, accessible omics data for the research community. In the context of multi-omics epigenetics research, four resources are particularly fundamental: The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), the Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium, and the PRoteomics IDEntifications (PRIDE) database. These repositories provide comprehensive genomic, transcriptomic, epigenomic, and proteomic data that enable researchers to investigate the complex interactions between genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors in health and disease. The integration of these diverse data types through bioinformatics pipelines allows for a more complete understanding of biological systems, accelerating the development of novel diagnostics and therapeutics. This guide provides a detailed overview of these essential resources, their data structures, access protocols, and practical applications in integrative bioinformatics research.

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, data types, and access information for the four featured public repositories, providing researchers with a quick reference for selecting appropriate resources for their multi-omics studies.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Major Public Data Repositories

| Repository | Primary Focus | Key Data Types | Data Volume | Access Method | Unique Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas) [13] | Cancer genomics | Genomic, epigenomic, transcriptomic, proteomic | Over 2.5 petabytes from 20,000+ samples across 33 cancer types [13] | Genomic Data Commons (GDC) Data Portal [13] [14] | Clinical data linked to molecular profiles; Pan-cancer atlas |

| GEO (Gene Expression Omnibus) [15] | Functional genomics | Gene expression, epigenomics, genotyping | International repository with millions of samples [15] | Web interface; FTP bulk download [15] | Flexible submission format; Curated DataSets and gene Profiles |

| Roadmap Epigenomics [16] [17] | Reference epigenomes | Histone modifications, DNA methylation, chromatin accessibility | 111+ consolidated reference human epigenomes [17] | GEO repository; Specialized web portal [16] [17] | Integrated analysis of epigenomes across cell types and tissues |

| PRIDE (PRoteomics IDEntifications) [18] | Mass spectrometry proteomics | Protein and peptide identifications, post-translational modifications | Data from ~60 species, largest fraction from human samples [18] | Web interface; PRIDE Inspector tool; API [18] | ProteomeXchange consortium member; Standards-compliant repository |

Repository-Specific Data Access Protocols

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Access Workflow

TCGA provides a comprehensive resource for cancer researchers, with data accessible through a structured pipeline. The following protocol outlines the key steps for accessing and utilizing TCGA data:

Table 2: TCGA Data Access Protocol

| Step | Procedure | Tools/Platform | Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Data Discovery | Navigate to the Genomic Data Commons (GDC) Data Portal | GDC Data Portal [13] [14] | List of available cancer types and associated molecular data |

| 2. Data Selection | Select cases based on disease type, project, demographic, or molecular criteria | GDC Data Portal Query Interface [13] | Cart with selected cases and file manifests |

| 3. Data Download | Use the GDC Data Transfer Tool for efficient bulk download | GDC Data Transfer Tool [13] | Local directory with genomic data files (BAM, VCF, etc.) |

| 4. Data Analysis | Apply computational tools for genomic analysis | GDC Analysis Tools or external pipelines [13] | Analyzed genomic data integrated with clinical information |

Important Considerations for TCGA Data Usage: TCGA data is available for public research use; however, researchers should note that biological samples and materials cannot be redistributed under any circumstances, as all cases were consented specifically for TCGA research and tissue samples have largely been depleted through prior analyses [14].

GEO Data Retrieval and Analysis Protocol

GEO serves as a versatile repository for high-throughput functional genomics data. The protocol below details the process for locating and analyzing relevant datasets:

- Dataset Identification: Use the GEO DataSets interface with targeted queries combining keywords (e.g., "DNA methylation"), organism (e.g., "Homo sapiens"), and experimental factors (e.g., "cancer") [15].

- Data Structure Assessment: Examine the GEO record organization, which includes Platform (GPL), Sample (GSM), and Series (GSE) records, to understand experimental design and data compatibility [15].

- Data Retrieval: Download complete datasets using the "Series Matrix" files or raw data via FTP links provided on the GEO record. For curated DataSets, utilize GEO's built-in analysis tools [15].

- Profile Analysis: Use the GEO Profiles database to examine expression patterns of individual genes across selected studies, identifying similarly expressed genes or chromosomal neighbors [15].

Roadmap Epigenomics Data Extraction Protocol

The Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium provides comprehensive reference epigenomes. The following workflow outlines the data access process:

Roadmap Epigenomics Data Access Workflow

Implementation Notes: The Roadmap Web Portal provides a grid visualization tool that enables researchers to select multiple epigenomes (rows) and data types (columns) for batch processing and download [17]. Data is available in standard formats including BAM (sequence alignments), WIG (genome track data), and BED (genomic regions), facilitating integration with common bioinformatics workflows [16].

PRIDE Proteomics Data Access Protocol

PRIDE serves as a central repository for mass spectrometry-based proteomics data. The access protocol includes:

- Data Discovery: Search the PRIDE archive using the web interface, PRIDE Inspector tool, or programmatically via the RESTful API [18].

- Format Handling: Utilize PRIDE Converter tools to handle diverse mass spectrometry data formats and convert them to standard formats (mzML, mzIdentML) [18].

- Data Retrieval: Download complete datasets in PRIDE XML, mzML, or mzIdentML formats, depending on analysis requirements [18].

- ProteomeXchange Integration: For comprehensive data coverage, leverage the ProteomeXchange consortium, which provides coordinated access to multiple proteomics repositories [18].

Integrative Multi-Omics Analysis: A Practical Framework

Conceptual Framework for Multi-Omics Integration

The true power of public repositories emerges when data from multiple sources is integrated to address complex biological questions. The following diagram illustrates a conceptual framework for multi-omics integration:

Multi-Omics Data Integration Framework

Case Study: Integrated Epigenetics Analysis in Major Depressive Disorder

A recent study demonstrates the practical application of multi-omics integration using public repositories [19]. Researchers combined neuroimaging data, brain-wide gene expression from the Allen Human Brain Atlas, and peripheral DNA methylation data to investigate gray matter abnormalities in major depressive disorder (MDD). The successful workflow included:

- Data Acquisition: Obtaining MRI data from 269 patients and 416 controls, plus DNA methylation data from Illumina 850K arrays [19].

- Spatial Transcriptomics: Mapping gene expression patterns to brain structural deficits using AHBA data [19].

- Epigenomic Integration: Identifying differentially methylated positions (DMPs) and correlating them with both gene expression and gray matter volume changes [19].

- Pathway Analysis: Enrichment analysis revealed that DMPs associated with gray matter changes were primarily involved in neurodevelopmental and synaptic transmission processes [19].

This case study exemplifies how data from different repositories and experimental sources can be integrated to uncover novel biological mechanisms underlying complex diseases.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Multi-Omics Research

| Category | Resource/Tool | Specific Application | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Retrieval Tools | GDC Data Transfer Tool [13] | TCGA data download | Efficient bulk transfer of genomic data files |

| PRIDE Inspector [18] | Proteomics data visualization | Standalone tool for browsing and analyzing PRIDE datasets | |

| GEO2R [15] | GEO data analysis | Web tool for identifying differentially expressed genes in GEO datasets | |

| Data Analysis Platforms | UCSC Genome Browser [16] | Epigenomic data visualization | Genome coordinate-based visualization of Roadmap and other epigenomic data |

| NCBI Sequence Viewer [16] | Genomic data visualization | Tool for viewing genomic sequences and annotations | |

| Experimental Assay Technologies | Illumina Methylation850 Array [19] | DNA methylation analysis | Genome-wide methylation profiling at 850,000 CpG sites |

| Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) [20] | Histone modification analysis | Protein-DNA interaction mapping for transcription factors and histone marks | |

| Bisulfite Sequencing [20] | DNA methylation analysis | Single-base resolution mapping of methylated cytosines | |

| ATAC-seq [20] | Chromatin accessibility | Identification of open chromatin regions using hyperactive Tn5 transposase | |

| Computational Languages | Python with GeoPandas/xarray [21] | Geospatial data analysis | Programming environment for processing both vector and raster geospatial data |

Public data repositories represent invaluable resources for advancing multi-omics research and precision medicine. TCGA, GEO, Roadmap Epigenomics, and PRIDE provide comprehensively annotated, large-scale datasets that enable researchers to explore complex biological systems without the need for generating all data de novo. As these repositories continue to grow and incorporate new data types, and as artificial intelligence technologies like machine learning and deep learning become more sophisticated [20], the potential for extracting novel biological insights through integrative analysis will expand significantly. Success in this domain requires both familiarity with the data access protocols outlined in this guide and development of robust computational frameworks capable of handling the volume and heterogeneity of multi-omics data. The continued curation and expansion of these public resources, coupled with advanced bioinformatics pipelines, will be essential for translating molecular data into clinical applications in the era of precision medicine.

Complex human diseases, such as neurodegenerative disorders and cancer, are not driven by alterations in a single molecular layer but arise from the dynamic interplay between the genome, epigenome, transcriptome, and proteome [7]. Traditional single-omics approaches, which analyze one type of biological molecule in isolation, provide a valuable but fundamentally limited view of this intricate system. They average signals across thousands to millions of heterogeneous cells, obscuring critical cellular nuances and causal relationships [22]. While single-omics studies have identified numerous disease-associated molecules, they often fail to distinguish causative drivers from correlative bystanders, hindering the development of effective diagnostics and therapeutics [23] [7].

The field is now undergoing a paradigm shift toward multi-omics integration, driven by the recognition that biological information flows through interconnected layers: from DNA to RNA to protein, with epigenetic mechanisms exerting regulatory control at each stage [23] [5]. This article delineates the theoretical and practical rationale for moving beyond single-omics, detailing how integrative bioinformatics pipelines are essential for constructing a comprehensive model of complex disease pathogenesis.

The Theoretical Imperative for Multi-Omics Integration

The Information Flow of the Central Dogma and Its Disruption in Disease

The "central dogma" of biology outlines a hierarchical flow of information, providing a logical framework for multi-omics investigation. Complex diseases often disrupt this flow at multiple points, and only an integrated approach can pinpoint these failures [23] [5]. For instance, a disease state may involve:

- A genetic variant (Genomics) that leads to

- Aberrant DNA methylation (Epigenomics), which prevents

- The expression of a key gene (Transcriptomics), resulting in

- A deficiency of a critical enzyme (Proteomics) and the subsequent

- Dysregulation of metabolic pathways (Metabolomics) [23].

A single-omics approach would capture only one fragment of this causal cascade. Multi-omics integration connects these layers, transforming a list of correlative observations into a mechanistic model of disease.

Cellular Heterogeneity: The Pitfall of Bulk Omics

Bulk omics methods, which analyze tissue samples as a whole, produce data that represents an average across all constituent cells. This averaging effect masks biologically significant variation. For example, bulk RNA sequencing of a tumor might detect the expression profile of the most abundant cell type while completely missing critical signals from rare, treatment-resistant cancer stem cells or infiltrating immune cells [22] [24].

Single-cell multi-omics technologies have emerged to address this fundamental limitation. By measuring multiple omics layers simultaneously within individual cells, they enable researchers to:

- Define novel cell subtypes based on coupled molecular features.

- Track cellular developmental trajectories and identify branching points during disease progression.

- Uncover rare cell populations that play an outsized role in disease mechanisms or therapeutic resistance [25] [22] [24].

Table 1: Key Single-Cell Multi-Omics Technologies for Resolving Heterogeneity

| Technology/Acronym | Omics Layers Measured | Primary Application in Disease Research |

|---|---|---|

| CITE-seq [26] | Transcriptome + Surface Proteins | Defining immune cell states in cancer and autoimmunity |

| scATAC-seq [25] [26] | Transcriptome + Chromatin Accessibility | Identifying regulatory programs driving cell fate in development and disease |

| G&T-seq [24] | Genome + Transcriptome | Linking somatic mutations to transcriptional phenotypes within single cells |

| SPLiT-seq [22] | Transcriptome (multiplexed) | Low-cost, high-throughput profiling of heterogeneous tissues |

| SCENIC+ [27] | Transcriptome + Chromatin Accessibility | Inferring gene regulatory networks and key transcription factors |

Practical Applications: Multi-Omics Insights in Complex Diseases

Elucidating Neurodegenerative Pathways

In Alzheimer's disease (AD), single-omics studies have identified characteristic amyloid-beta plaques, tau tangles, and transcriptional changes. However, multi-omics integration is revealing the deeper, interconnected pathological network. Data mining studies that integrate epigenomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic datasets have shown that DNA methylation variations can influence the deposition of both amyloid-beta and tau, connecting epigenetic dysregulation to core pathological hallmarks [7]. Furthermore, integrative analyses have begun to classify clinically relevant subgroups of AD patients, which is a critical step toward personalized medicine [7].

Refining Cancer Subtyping and Biomarker Discovery

In oncology, multi-omics integration has moved beyond transcriptomic-based classification to provide a more robust molecular taxonomy of tumors. For example, studies integrating genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data from colorectal cancer have identified that the chromosome 20q amplicon is associated with coordinated changes at both the mRNA and protein levels. This integrated view helped prioritize potential driver genes, such as HNF4A and SRC, which were not apparent from genomic data alone [28]. Similarly, in prostate cancer, the integration of metabolomics and transcriptomics pinpointed the metabolite sphingosine and its associated signaling pathway as a specific distinguisher from benign hyperplasia and a potential therapeutic target [28].

Protocols for Multi-Omics Data Integration

A Standardized Workflow for Multi-Omics Analysis

A robust multi-omics integration pipeline involves sequential steps to ensure data quality and meaningful interpretation.

Detailed Protocol: Multi-Omics Integration with Reference Materials

Objective: To integrate transcriptomic and epigenomic data from a disease cohort using reference materials for quality control.

Materials:

- Quartet Reference Materials: Matched DNA, RNA, and protein from immortalized cell lines derived from a family quartet (parents and monozygotic twins). These provide built-in ground truth for quality assessment [5].

- Study Samples: Patient and control tissues (e.g., frozen biopsies or PBMCs).

- Key Software Tools: FastQC, Trimmomatic, BWA (genomics), Cell Ranger (single-cell), Seurat, MOFA+, Scanorama.

Procedure:

Sample Preparation and Sequencing:

- Extract DNA and RNA from all study samples and the Quartet reference materials simultaneously.

- Perform library preparation for whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and RNA-seq (bulk or single-cell) for all samples in the same batch.

- Sequence all libraries on the same platform to minimize technical variation.

Horizontal Integration (Within-Omics QC and Batch Correction):

- Quality Control: Process raw sequencing data (FASTQ files). Use FastQC for initial quality reports. Trim adapters and low-quality bases with Trimmomatic [23].

- Alignment and Quantification: Align reads to the reference genome (e.g., using BWA for WGS or STAR for RNA-seq). Generate feature count matrices [23].

- Ratio-Based Profiling (Key Step): Scale the absolute feature values of study samples relative to those of the concurrently measured Quartet reference sample (e.g., D6) on a feature-by-feature basis. This ratio-based approach dramatically improves data reproducibility and comparability across batches and platforms [5].

- Batch Correction: Use tools like Harmony or Scanorama to correct for remaining batch effects within the transcriptomics and epigenomics datasets separately, using the Quartet data to guide and validate the process.

Vertical Integration (Cross-Omics Integration):

- Data Matching: Organize data so that multi-omics measurements from the same sample are linked.

- Choose an Integration Strategy:

- For Matched Data: Use a vertical integration tool like MOFA+, which applies factor analysis to decompose the multi-omics data into a set of latent factors that represent the shared and specific sources of variation across omics layers [27] [23].

- For Unmatched Data: If transcriptomic and epigenomic data come from different cells of the same sample, use an unmatched (diagonal) integration tool like GLUE (Graph-Linked Unified Embedding), which uses a graph-based variational autoencoder and prior biological knowledge to align the datasets in a common space [27].

- Run Integration: Input the normalized and batch-corrected matrices from each omics layer into the chosen tool.

Downstream Analysis and Validation:

- Clustering: Identify sample clusters or cell states based on the integrated latent factors or embeddings. Validate that the Quartet samples cluster into the expected three genetically distinct groups (twins, father, mother) [5].

- Network Inference: Identify cross-omics regulatory networks. For example, look for correlations between genetic variants, chromatin accessibility peaks, and gene expression levels that follow the central dogma [23] [5].

- Biological Validation: Prioritize key integrated findings (e.g., a dysregulated pathway) for experimental validation using targeted assays in model systems.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

| Category | Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Materials | Quartet Project Suites [5] | Provides matched DNA, RNA, protein from a family quartet for ground truth QC and ratio-based profiling. |

| Single-Cell Isolation | Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) [22] [24] | High-specificity isolation of single cells based on surface markers for plate-based sequencing. |

| Single-Cell Isolation | 10X Genomics Microfluidic Chips [22] | High-throughput, droplet-based isolation of thousands of single cells for barcoding and library prep. |

| Computational Tools (Matched Integration) | Seurat v4/v5 [27] | Weighted nearest neighbor (WNN) integration for multi-modal data like RNA + ATAC or RNA + protein. |

| Computational Tools (Matched Integration) | MOFA+ [27] [23] | Factor analysis model to discover the principal sources of variation across multiple omics data types. |

| Computational Tools (Unmatched Integration) | GLUE [27] | Graph-linked variational autoencoder for integrating unpaired multi-omics data using prior biological knowledge. |

| Computational Tools (Mosaic Integration) | StabMap [25] [27] | Mosaic data integration for datasets with only partially overlapping omics measurements. |

The limitations of single-omics analysis in modeling complex diseases are no longer speculative but are empirically demonstrated. Its inability to resolve cellular heterogeneity, its provision of correlative rather than causal insights, and its fragmented view of biological systems fundamentally restrict its utility in unraveling complex pathogenesis [23] [22]. The integration of multi-omics data within a unified bioinformatics pipeline is no longer an optional advanced technique but a necessary paradigm for meaningful progress in biomedical research. By systematically combining data across genomic, epigenomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic layers—supported by standardized reference materials and sophisticated computational tools—researchers can now construct predictive, mechanistic models of disease. This holistic approach is paving the way for refined disease subtyping, the discovery of novel biomarkers, and the development of targeted, personalized therapeutic strategies [7] [28] [29].

Systems Bioinformatics is an interdisciplinary field that lies at the intersection of systems biology and classical bioinformatics. It represents a paradigm shift from reductionist molecular biology to a holistic approach for understanding biological regulation [30]. This field focuses on integrating information across different biological levels using a bottom-up approach from systems biology combined with the data-driven top-down approach of bioinformatics [30].

The core premise of Systems Bioinformatics is that biological mechanisms consist of numerous synergistic effects emerging from various systems of interwoven biomolecules, cells, and tissues. Therefore, it aims to reveal the behavior of the system as a whole rather than as the mere sum of its parts [30]. This approach is particularly powerful for bridging the gap between genotype and phenotype, providing critical insights for biomarker discovery and therapeutic development [30].

Key Principles and Methodologies

The Holistic Framework

Systems Bioinformatics addresses biological complexity through several core principles that distinguish it from traditional approaches:

Network-Centric Analysis: Biological systems are represented as complex networks where nodes represent cellular components and edges represent their interactions [30]. This framework allows researchers to study emergent properties such as homeostasis, adaptivity, and modularity [30].

Multi-Scale Integration: It integrates information across multiple biological scales, from molecular and cellular levels to tissue and organism levels [31] [30]. This integration is essential for understanding how interactions at smaller scales give rise to functions at larger scales.

Data-Driven Modeling: The field leverages advanced computational approaches including statistical inference, probabilistic models, graph theory, and machine learning to extract meaningful patterns from large, heterogeneous datasets [30].

Essential Methodological Approaches

Table 1: Core Methodological Approaches in Systems Bioinformatics

| Method Category | Key Techniques | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Network Science | Graph theory, topology analysis, community detection, centrality measures | Mapping biological interactions, identifying key regulatory elements [30] |

| Data Integration | Multi-omics integration, network mapping, statistical harmonization | Combining disparate data types into unified models [32] [30] |

| Computational Intelligence | Machine learning, deep learning, pattern recognition, data mining | Predictive modeling, biomarker discovery, drug response prediction [30] |

| Mathematical Modeling | Dynamical systems, kinetic modeling, simulation algorithms | Understanding system dynamics, predicting emergent behaviors [33] [30] |

Multi-Omics Integration in Epigenetics Research

The Multi-Omics Spectrum

Systems Bioinformatics provides the essential framework for integrating multi-omics data, which is particularly crucial for epigenetics research. The omics spectrum encompasses genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, epigenomics, pharmacogenomics, metagenomics, and metabolomics [30]. Each layer provides complementary information about biological regulation:

- Genomics identifies genetic variants and potential regulatory elements

- Epigenomics reveals chromatin modifications, DNA methylation patterns, and histone modifications

- Transcriptomics profiles gene expression patterns and regulatory RNAs

- Proteomics characterizes protein expression, post-translational modifications, and interactions

Network Integration Strategy

A key innovation in Systems Bioinformatics is the construction of multiple networks representing each level of the omics spectrum and their integration into a layered network that exchanges information within and between layers [30]. This approach involves:

Individual Layer Networks: Constructing separate networks for each omics data type (e.g., gene co-expression networks, protein-protein interaction networks, epigenetic regulation networks)

Cross-Layer Mapping: Establishing connections between different network layers based on known biological relationships (e.g., transcription factors to their target genes, metabolic enzymes to their metabolites)

Emergent Property Analysis: Studying how interactions across layers give rise to system-level behaviors that cannot be predicted from individual layers alone

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Integrated Multi-Omics Analysis Protocol

Protocol 1: Network-Based Multi-Omics Integration

This protocol describes the process for integrating multiple omics datasets to identify master regulators in epigenetic regulation.

Materials and Reagents:

- High-quality biological samples (tissue, cells, or biofluids)

- Multi-omics profiling platforms (NGS for genomics/epigenomics, LC-MS/MS for proteomics, NMR/LC-MS for metabolomics)

- Computational infrastructure for big data analysis

- Network analysis software (Cytoscape, igraph, or custom pipelines)

Procedure:

Sample Preparation and Data Generation

- Extract DNA, RNA, proteins, and metabolites from matched samples

- Perform whole-genome bisulfite sequencing for DNA methylation analysis

- Conduct chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) for histone modifications

- Perform RNA sequencing for transcriptome profiling

- Conduct liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) for proteomic and metabolomic profiling

Data Preprocessing and Quality Control

- Apply appropriate normalization methods for each data type

- Conduct batch effect correction using ComBat or similar methods

- Perform quality assessment using principal component analysis and sample correlation

Individual Network Construction

- Create epigenetic regulatory networks using correlation or mutual information measures

- Construct gene co-expression networks using WGCNA or similar approaches

- Build protein-protein interaction networks using STRING database or experimental data

Cross-Omics Network Integration

- Map inter-layer connections based on known biological relationships

- Implement multi-layer community detection to identify cross-omics functional modules

- Apply network propagation algorithms to prioritize key regulatory elements

Validation and Experimental Follow-up

- Select top candidate regulators for functional validation

- Perform perturbation experiments (CRISPR knockdown, pharmacological inhibition)

- Measure downstream effects using targeted assays

Protocol for Predictive Model Development

Protocol 2: Development of Predictive Models for Epigenetic Regulation

This protocol outlines the steps for creating computational models that can predict cellular behaviors and drug responses based on multi-omics epigenetic data.

Materials:

- Multi-omics datasets with clinical annotations

- Machine learning libraries (scikit-learn, TensorFlow, PyTorch)

- High-performance computing resources

- Validation datasets (independent cohorts)

Procedure:

Feature Selection and Engineering

- Perform differential analysis to identify significant features across omics layers

- Conduct dimension reduction using PCA, t-SNE, or UMAP

- Select biologically relevant features using domain knowledge

Model Training

- Implement ensemble methods (random forests, gradient boosting) for robust prediction

- Train neural networks for capturing non-linear relationships

- Apply cross-validation to optimize hyperparameters

Model Validation

- Test model performance on independent validation datasets

- Assess clinical relevance using survival analysis or treatment response data

- Compare against existing biomarkers or clinical standards

Biological Interpretation

- Conduct pathway enrichment analysis on important features

- Map predictive features to biological networks

- Generate hypotheses for mechanistic follow-up

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Systems Bioinformatics

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Reagents | Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing kits, ChIP-seq kits, RNA-seq libraries | Profiling epigenetic modifications, transcriptome dynamics | Multi-omics data generation [32] |

| Mass Spectrometry Reagents | TMT/Isobaric tags, trypsin digestion kits, metabolite extraction kits | Quantitative proteomics and metabolomics | Protein post-translational modification analysis, metabolic profiling [32] |

| Computational Frameworks | Network analysis tools (Cytoscape, NetworkX), ML libraries (scikit-learn, PyTorch) | Data integration, pattern recognition, predictive modeling | Network construction and analysis [30] |

| Database Resources | STRING, KEGG, Reactome, ENCODE, TCGA | Reference data for network building, pathway analysis | Biological context interpretation [30] |

| Visualization Tools | Gephi, ggplot2, Plotly, Circos | Data exploration, result communication | Multi-omics data visualization [30] |

Signaling Pathways and Network Architecture

Integrated Epigenetic Regulatory Network

Biological regulation in Systems Bioinformatics is understood through interconnected networks that span multiple organizational layers. The following diagram illustrates a typical epigenetic regulatory network that integrates multiple omics layers:

Multi-Omics Data Integration Architecture

The power of Systems Bioinformatics lies in its ability to integrate diverse data types through a structured computational architecture:

Applications in Drug Development and Precision Medicine

Advancing Therapeutic Development

Systems Bioinformatics significantly enhances drug development through several key applications:

Drug Repurposing: Network-based approaches identify new therapeutic indications for existing drugs by analyzing their effects on entire biological networks rather than single targets [30].

Biomarker Discovery: Multi-omics integration enables identification of robust biomarker signatures that capture the complexity of disease states, moving beyond single-molecule biomarkers [30].

Patient Stratification: Machine learning applied to multi-omics data identifies distinct patient subgroups with different disease drivers and treatment responses, enabling more targeted clinical trials and personalized treatment strategies [32] [30].

Mechanistic Understanding: By mapping drug effects across multiple biological layers, Systems Bioinformatics provides comprehensive understanding of therapeutic mechanisms and resistance pathways [30].

Quantitative Applications in Precision Medicine

Table 3: Quantitative Applications of Systems Bioinformatics in Medicine

| Application Area | Key Metrics | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Diagnostics | Prediction accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, AUC | Enhanced disease classification and early detection through multi-parameter models [30] |

| Computational Therapeutics | Drug response prediction accuracy, mechanism of action analysis | Improved treatment selection and identification of combination therapies [30] |

| Clinical Trial Optimization | Patient stratification accuracy, biomarker validation | More efficient trial designs and higher success rates [32] |

| Personalized Treatment | Individual outcome prediction, toxicity risk assessment | Tailored therapeutic strategies based on comprehensive patient profiling [30] |

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of Systems Bioinformatics is rapidly evolving, with several key trends shaping its future development in epigenetics research:

Single-Cell Multi-Omics: Emerging technologies enable multi-omics profiling at single-cell resolution, revealing cellular heterogeneity and rare cell populations in epigenetic regulation [32].

Temporal Dynamics: Integration of time-series data captures the dynamic nature of epigenetic regulation and cellular responses to perturbations [33].

Spatial Omics: Spatial transcriptomics and proteomics technologies incorporate geographical information into multi-omics networks, revealing tissue-level organization [32].

AI and Deep Learning: Advanced computational methods extract complex patterns from high-dimensional multi-omics data, enabling more accurate predictions of cellular behavior and drug responses [32] [30].

Digital Twins: The development of virtual patient models using real-world data enables simulation of individual responses to treatments under various conditions [31].

Advanced Data Fusion: Computational Strategies and AI-Driven Workflows for Multi-Omics Epigenetics

The advent of high-throughput technologies has generated an ever-growing number of omics data that seek to portray different but complementary biological layers including genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics [28] [34]. Multi-omics data integration provides a comprehensive view of biological systems by combining these various molecular layers, enabling researchers to uncover intricate molecular mechanisms underlying complex diseases and improve diagnostics and therapeutic strategies [28] [35]. Integrated approaches combine individual omics data to understand the interplay of molecules and assess the flow of information from one omics level to another, thereby bridging the gap from genotype to phenotype [28].

The convergence of multiple scientific disciplines and technological advances has positioned multi-omics as a transformative force in health diagnostics and therapeutic strategies [36]. By virtue of its ability to study biological phenomena holistically, multi-omics integration has demonstrated potential to improve prognostics and predictive accuracy of disease phenotypes, ultimately aiding in better treatment and prevention strategies [28] [12]. The field has witnessed unprecedented growth, with scientific publications more than doubling within just two years (2022-2023) since its first referenced mention in 2002 [36].

The fundamental challenge in multi-omics integration lies in cohesively combining and normalizing data across varied omics platforms and experimental methods [36]. Furthermore, the sheer volume and high dimensionality of multi-omics datasets necessitates sophisticated computational utilities and stringent statistical methodologies to ensure accurate data interpretation [36]. This review focuses on the three primary computational strategies adopted for multi-omics data fusion—early, intermediate, and late integration—and their applications in biomedical research and precision medicine.

Integration Paradigms: Conceptual Frameworks and Methodologies

Multi-omics data integration strategies are needed to combine the complementary knowledge brought by each omics layer [34]. These methods can be broadly categorized into five distinct approaches: early, mixed, intermediate, late, and hierarchical integration [34]. For the purpose of this review, we will focus on the three primary paradigms: early (data-level), intermediate (feature-level), and late (decision-level) fusion.

Table 1: Comparison of Multi-Omics Data Integration Paradigms

| Integration Paradigm | Technical Approach | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Fusion | Concatenates all omics datasets into a single matrix before analysis [34] | Preserves cross-omics correlations; enables discovery of novel interactions [34] [37] | High dimensionality; risk of overfitting; requires complete datasets [38] [37] | Small-scale datasets with minimal missing values; hypothesis generation |

| Intermediate Fusion | Simultaneously transforms original datasets into common and omics-specific representations [34] [39] | Balances shared and specific signals; handles heterogeneity better than early fusion [34] [37] | Complex implementation; requires specialized algorithms [34] | Exploring complementary omics patterns; medium-sized datasets |

| Late Fusion | Analyzes each omics separately and combines final predictions [34] [40] | Resistant to overfitting; handles data heterogeneity; works with missing modalities [40] [38] | May miss subtle cross-omics interactions; requires separate models for each type [34] | Clinical applications with missing data; predictive modeling |

Early Integration (Data-Level Fusion)

Early integration, also known as data-level fusion, involves concatenating all omics datasets into a single matrix on which machine learning models can be applied [34]. This approach combines raw data from multiple omics sources before any analysis takes place, creating a unified feature space that encompasses all molecular measurements. The fundamental premise of early integration is that by analyzing all data simultaneously, the model can capture complex interactions and correlations across different omics layers that might be missed when analyzing each layer independently.

The technical implementation of early integration typically involves substantial preprocessing and normalization to make different omics measurements comparable [34]. This may include batch effect correction, variance stabilization, and scaling to address the significant technical variations between different omics platforms. Following preprocessing, features from genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and other omics layers are combined into a single matrix where rows represent samples and columns represent all measured features across omics layers.

While early integration preserves potential cross-omics correlations and enables discovery of novel interactions, it creates significant analytical challenges due to the "curse of dimensionality" [38] [37]. The concatenated data matrix often has dramatically more features (p) than samples (n), creating high-dimensional data spaces where the risk of overfitting is substantial. This approach also requires complete datasets across all omics layers for all samples, which can be difficult to achieve in practical research settings where missing data is common [35].

Intermediate Integration (Feature-Level Fusion)

Intermediate integration, also referred to as feature-level fusion, involves simultaneously transforming the original datasets into common and omics-specific representations [34]. This approach does not combine raw data directly but rather processes each omics dataset to extract latent features that are then integrated at a intermediate level of abstraction. The core objective is to identify shared patterns across omics layers while still preserving omics-specific signals that may be biologically important.

This integration paradigm employs sophisticated computational techniques including matrix factorization, multi-omics clustering, and deep learning approaches such as autoencoders [39] [37]. These methods project different omics data types into a common latent space where biological patterns can be identified without being obscured by technical variations between platforms. For example, joint matrix decomposition methods factorize multiple omics matrices to identify shared components that represent coordinated biological signals across molecular layers.

Intermediate integration offers a balanced approach that can handle data heterogeneity more effectively than early integration while capturing more cross-omics relationships than late integration [34]. However, it requires specialized algorithms and often involves more complex implementation than other approaches. The interpretation of latent features can also be challenging, as these may not directly correspond to specific biological entities measured by the original assays.

Late Integration (Decision-Level Fusion)

Late integration, known as decision-level fusion, analyzes each omics dataset separately and combines their final predictions [34] [40]. In this approach, separate machine learning models are trained for each omics modality, and their outputs are integrated at the decision level through various ensemble methods. This strategy maintains the distinct characteristics of each data type while leveraging their complementary predictive power.

The technical implementation of late integration involves training independent models for each omics type on their respective data [40]. These models learn patterns specific to each molecular layer. Their predictions—which may be class labels, probabilities, or continuous values—are then combined using methods such as weighted averaging, voting schemes, or meta-learners [40] [38]. The weights for combination can be optimized based on validation performance or prior knowledge of each modality's reliability.

Late fusion provides several practical advantages, particularly for biomedical applications [40] [38]. It is naturally resistant to overfitting because each model is trained on a lower-dimensional space compared to early integration. It can gracefully handle missing modalities—if data for one omics type is unavailable for certain samples, predictions can still be made using the available modalities. This approach also accommodates data heterogeneity more easily, as each model can be specifically designed for the characteristics of its data type.

Performance Comparison and Quantitative Assessment

Numerous studies have systematically compared the performance of different integration strategies across various biomedical applications. The comparative effectiveness of each paradigm depends on multiple factors including data characteristics, sample size, and the specific biological question being addressed.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Fusion Approaches in Cancer Classification

| Study | Application | Data Modalities | Early Fusion Performance | Intermediate Fusion Performance | Late Fusion Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| López et al., 2022 [40] | NSCLC Subtype Classification | RNA-Seq, miRNA-Seq, WSI, CNV, DNA methylation | N/A | N/A | F1: 96.81%, AUC: 0.993, AUPRC: 0.980 |

| AstraZeneca AI, 2025 [38] | Cancer Survival Prediction | Transcripts, proteins, metabolites, clinical factors | Lower performance due to overfitting | Moderate performance | Superior performance (C-index improvement) |

| TransFuse, 2025 [35] | Alzheimer's Disease Classification | SNPs, gene expression, proteins | Accuracy: ~85% (with complete data only) | Accuracy: ~87% | Accuracy: 89% (with incomplete data) |