From Association to Function: Advanced Strategies for Validating EWAS Hits in Disease Research

Epigenome-Wide Association Studies (EWAS) have become a cornerstone for identifying epigenetic variants, primarily DNA methylation marks, associated with complex diseases.

From Association to Function: Advanced Strategies for Validating EWAS Hits in Disease Research

Abstract

Epigenome-Wide Association Studies (EWAS) have become a cornerstone for identifying epigenetic variants, primarily DNA methylation marks, associated with complex diseases. However, moving from statistically significant 'hits' to understanding their functional biological role presents a major challenge. This article provides a comprehensive, step-by-step framework for the functional follow-up of EWAS findings. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers foundational concepts, advanced methodological pipelines, strategies to overcome common analytical challenges, and robust validation techniques. By integrating current bioinformatic tools and experimental approaches, this guide aims to bridge the gap between epigenetic discovery and mechanistic insight, ultimately accelerating the translation of EWAS findings into biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

Laying the Groundwork: Understanding Your EWAS Hits and Their Biological Context

Epigenome-wide association studies (EWAS) investigate genome-wide epigenetic variants, most commonly DNA methylation, to identify statistically significant associations with phenotypes of interest [1]. The primary outputs of these analyses are Differentially Methylated Positions (DMPs), single CpG dinucleotides that show statistically significant differences between comparison groups, and Differentially Methylated Regions (DMRs), genomic regions containing multiple adjacent DMPs that collectively demonstrate association [1]. Successfully navigating the path from these initial statistical hits to understanding their functional biological significance represents a critical challenge in epigenomic research. This guide provides a structured framework for interpreting EWAS output and designing appropriate functional validation strategies within the context of a broader thesis on functional follow-up of EWAS hits.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Analysis and Interpretation

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between a DMP and a DMR, and which should I prioritize for follow-up?

A: A DMP is a single CpG site that passes statistical significance thresholds for differential methylation, while a DMR is a genomic region containing multiple adjacent DMPs that collectively show association [1]. DMRs are often more biologically relevant and stable than individual DMPs because coordinated methylation changes across multiple CpGs are less likely to represent technical artifacts and more likely to significantly impact gene regulation [2]. Prioritize DMRs or DMPs located in functional genomic elements (promoters, enhancers) that are associated with genes having plausible biological connections to your phenotype.

Q2: What statistical thresholds should I use to define significant DMPs in my EWAS?

A: For EPIC array data measuring ~850,000 CpG sites, the Bonferroni-corrected significance threshold is approximately p < 6 × 10⁻⁸ [3]. However, many studies also consider a suggestive threshold of p < 1 × 10⁻⁵ for initial discovery [3] [4]. The Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) correction is a less stringent alternative that balances discovery with type I error control [2]. The choice depends on your study goals—Bonferroni for high-confidence hits, FDR for exploratory discovery.

Q3: How can I determine if my DMPs or DMRs are functionally relevant to gene regulation?

A: Several analytical approaches can help assess functional potential:

- Genomic annotation: Map significant CpGs to functional genomic elements using databases like ENCODE and FANTOM5. Promoter and enhancer regions are particularly important [1].

- Methylation quantitative trait loci (methQTL) analysis: Identify genetic variants that influence methylation levels at your significant sites, connecting genetic and epigenetic regulation [1].

- Expression quantitative trait methylation (eQTM) analysis: Test for correlations between methylation levels of your significant CpGs and gene expression levels in relevant tissues [5].

- Pathway enrichment analysis: Tools like Gene Ontology and KEGG can identify biological pathways overrepresented among genes near your significant DMPs/DMRs [5] [4].

Q4: My EWAS identified significant DMPs, but they are in genes with no obvious connection to my phenotype. How should I proceed?

A: This common scenario requires careful consideration:

- Evaluate genomic context: Intergenic DMPs may regulate distant genes through chromatin looping. Use chromatin interaction data (Hi-C) from relevant cell types.

- Assess co-regulation patterns: MethQTL and eQTM analyses may reveal connections to biologically relevant genes [5].

- Consider novel biology: EWAS can reveal entirely new biological mechanisms. Use functional validation experiments to test whether these apparently unrelated genes truly influence your phenotype.

Technical and Experimental Design

Q5: What are the main advantages of longitudinal EWAS designs compared to case-control studies?

A: Case-control EWAS are more common due to practicality and cost, but they cannot determine whether methylation differences cause disease or result from it [1]. Longitudinal studies measuring methylation at multiple timepoints can track intra-individual changes in relation to phenotype development, potentially establishing temporal relationships and causal inference [1]. For disease progression studies, consider linear mixed-effects models in tools like easyEWAS to analyze longitudinal methylation data [2].

Q6: How can I address cell type heterogeneity in blood-based EWAS?

A: Blood contains multiple cell types with distinct methylation profiles. Always use statistical deconvolution methods to estimate and adjust for cell type composition [1] [5]. For cord blood studies, specifically use the FlowSorted.CordBloodCombined.450k package with methods like estimateCellCounts2 to account for nucleated red blood cells unique to cord blood [5]. Failure to adjust for cell type composition is a major source of false positives in EWAS.

Q7: What validation approaches should I consider for my top EWAS hits?

A: Robust validation requires multiple approaches:

- Technical replication: Repeat methylation measurement of top hits using alternative methods (pyrosequencing, targeted bisulfite sequencing).

- Biological replication: Confirm findings in an independent cohort.

- Internal validation: Use bootstrap resampling to assess the stability of effect size estimates [2].

- Functional validation: Implement experimental approaches described in the Functional Follow-up Framework section below.

Troubleshooting Common EWAS Workflow Issues

Low DNA Methylation Signal

Problem: During methylated DNA enrichment, you observe very little or no methylated DNA, with MBD protein binding non-methylated DNA.

Solution: Follow the appropriate protocol for your DNA input amount. The product manual typically specifies different protocols for different input ranges. For low DNA inputs, use specialized low-input protocols to maintain specificity [6].

Poor Bisulfite Conversion Efficiency

Problem: Incomplete bisulfite conversion leads to inaccurate methylation measurements.

Solution: Ensure high DNA purity before conversion. If particulate matter is present after adding conversion reagent, centrifuge at high speed and use only the clear supernatant. Verify all liquid is at the bottom of the tube before conversion [6].

Amplification Challenges with Bisulfite-Converted DNA

Problem: Difficulty amplifying bisulfite-converted DNA templates.

Solution:

- Primer design: Design primers 24-32 nts in length with no more than 2-3 mixed bases. Avoid 3' ends with mixed bases or residues of unknown conversion state.

- Polymerase selection: Use hot-start Taq polymerase (Platinum Taq, AccuPrime Taq). Avoid proof-reading polymerases as they cannot read through uracil.

- Amplicon size: Target ~200 bp fragments. Larger amplicons require optimized protocols due to bisulfite-induced strand breaks.

- Template DNA: Use 2-4 µl of eluted DNA per PCR reaction, keeping total template under 500 ng [6].

Functional Follow-up Framework: From Statistical Hit to Biological Mechanism

Step 1: Prioritize EWAS Hits for Functional Validation

Systematically evaluate and rank your significant DMPs/DMRs using this multi-criteria approach:

Table: DMP/DMR Prioritization Criteria

| Priority Tier | Statistical Evidence | Genomic Context | Biological Plausibility | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Bonferroni-significant DMR; Consistent across cohorts | Gene promoter; Enhancer; Known regulatory region | Gene function directly related to phenotype; eQTM support | Probes without known SNPs; Good detection p-values |

| Medium | Suggestive DMR or Bonferroni DMP | Gene body; 3' UTR; Conserved non-coding | Gene in relevant pathway; Limited prior evidence | Passes quality control after preprocessing |

| Low | Suggestive DMP only | Intergenic without annotation | No known connection to phenotype | Located in problematic genomic region |

Step 2: Select Appropriate Functional Validation Experiments

Based on your prioritized hits, choose experimental approaches that match your research questions and available resources:

Table: Functional Validation Experimental Approaches

| Experimental Approach | Primary Research Question | Key Output Measures | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro methylation editing | Does targeted methylation alteration directly affect gene expression? | Gene expression changes; Phenotypic readouts | CRISPR-dCas9 systems with DNMT3A/ TET1 domains; Control for off-target effects |

| Methylation quantitative trait loci (methQTL) analysis [1] | Do genetic variants influence methylation at this locus? | Genetic variant-methylation associations | Requires genotype data; Large sample sizes increase power |

| Expression quantitative trait methylation (eQTM) analysis [5] | Does methylation correlate with gene expression in relevant tissue? | Correlation between methylation beta values and RNA expression | Need matched methylation and expression data; Tissue-specific effects |

| Pathway enrichment analysis [4] | Are significant genes enriched in specific biological pathways? | Enriched GO terms; KEGG pathways | Use specialized packages (methylglm); Correct for multiple testing |

| 3D chromatin interaction mapping | Do intergenic DMPs physically interact with candidate genes? | Chromatin looping; Enhancer-promoter contacts | Hi-C; ChIA-PET; Requires specific expertise and resources |

Step 3: Implement an Integrated Analysis Workflow

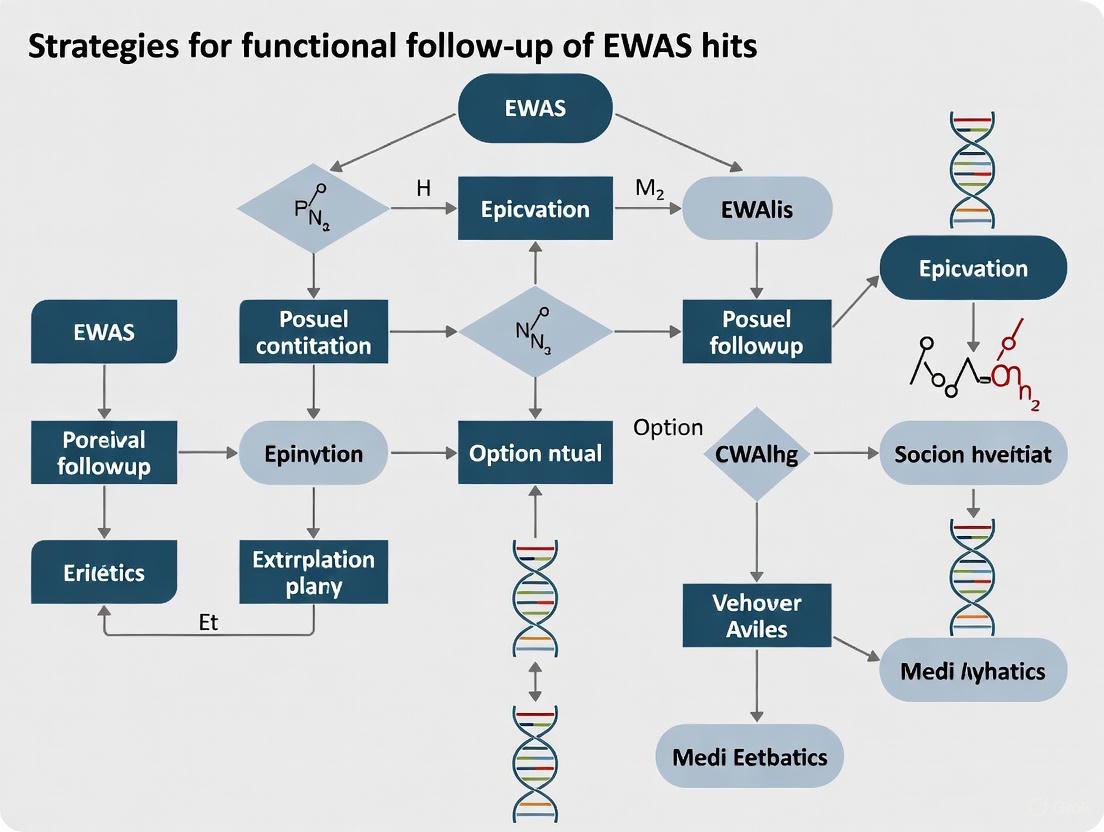

The following workflow diagram illustrates the comprehensive path from raw EWAS data to biological insight:

Table: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for EWAS Follow-up

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioinformatic Pipelines | ChAMP [1], Minfi [1], easyEWAS [2] | Raw data processing, normalization, DMP/DMR detection | Initial EWAS analysis; Accessible tools for non-bioinformaticians |

| Methylation Arrays | Infinium MethylationEPIC v2.0 [3], HumanMethylation450 [5] | Genome-wide methylation profiling | Primary discovery phase; Large cohort studies |

| Functional Annotation | Gene Ontology [5], KEGG [5], ENCODE, FANTOM5 [1] | Genomic context and pathway analysis | Interpreting significant hits; Generating biological hypotheses |

| Validation Technologies | Pyrosequencing, Targeted bisulfite sequencing | Technical validation of array findings | Confirming top hits; Accurate quantification |

| Methylation Editors | CRISPR-dCas9-DNMT3A, CRISPR-dCas9-TET1 | Targeted alteration of methylation | Functional causality testing; Mechanism investigation |

| Cell Type Deconvolution | EstimateCellCounts2 [5], FlowSorted.CordBloodCombined.450k [5] | Blood cell composition estimation | Adjusting for cellular heterogeneity; Cord blood-specific applications |

Advanced Applications and Integration with Other Omics Data

Integrating EWAS with Genomic and Transcriptomic Data

Multi-omics integration significantly enhances the interpretation of EWAS results:

- Triangulate evidence by overlapping significant DMRs with GWAS risk loci for your phenotype [7]

- Incorporate methQTL analysis to identify genetic variants that influence methylation levels at your significant sites [1]

- Perform eQTM analysis to connect methylation changes with gene expression alterations [5]

- Apply Mendelian randomization approaches to infer causal relationships between methylation and phenotype [7]

Translating EWAS Findings to Clinical and Biomarker Applications

EWAS results have promising translational applications:

- Biomarker development: Methylation signatures can serve as diagnostic, prognostic, or treatment response biomarkers [3]

- Drug target identification: Genes with altered methylation in disease may represent novel therapeutic targets

- Elucidating disease mechanisms: Methylation patterns can reveal previously unknown biological pathways involved in disease pathogenesis [4]

Successfully navigating from initial EWAS associations to functional biological insight requires a systematic, multi-step approach that combines rigorous statistical analysis with thoughtful experimental design. By implementing the prioritization frameworks, troubleshooting guides, and validation strategies outlined in this technical support center, researchers can maximize the biological impact of their EWAS findings and make meaningful contributions to our understanding of epigenetic regulation in health and disease.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My EWAS identified hundreds of significant CpG sites. What is the first step to make this data biologically interpretable?

The crucial first step is genomic annotation. This involves mapping each differentially methylated position (DMP) to its genomic context to generate hypotheses about its function. You need to determine the location of each CpG relative to gene features like promoters, enhancers, and gene bodies [8]. This process helps prioritize hits that are more likely to regulate gene expression. Following annotation, you can use pathway analysis tools to see if the genes associated with your significant DMPs converge on specific biological processes [9] [8].

Q2: How does functional follow-up for EWAS hits differ from GWAS follow-up?

While both aim to understand the biology behind statistical hits, their starting points and key challenges differ. GWAS identifies causal genetic variants, whereas EWAS identifies epigenetic associations that can arise from forward causation, reverse causation, or confounding [10]. Therefore, an EWAS follow-up must carefully consider this causal uncertainty. Furthermore, EWAS hits are highly tissue-specific, so validation in a disease-relevant tissue is often more critical than for GWAS [8]. Finally, a key step in EWAS follow-up is integrating methylation quantitative trait loci (meQTL) analysis to determine if the methylation change is under genetic control or is driven by non-genetic factors [11] [12].

Q3: I am getting a low overlap between genes flagged by my EWAS and known GWAS genes for the same trait. Does this mean my results are invalid?

Not at all. Empirical and simulated data show that GWAS and EWAS often capture distinct genes and biological aspects of a complex trait [10]. A lack of substantial overlap can be expected because DNA methylation can mediate non-genetic effects (e.g., environmental exposures) and reflect downstream consequences of the disease state (reverse causation). Your EWAS may be uncovering a unique, non-genetic component of the disease biology.

Q4: What are the best methods for prioritizing annotated genes for functional validation?

There is no single "best" method, and a multi-faceted prioritization strategy is recommended. The table below summarizes key criteria and the data sources you can use to score and rank your candidate genes.

Table: A Multi-Factor Framework for Prioritizing Genes from EWAS Hits

| Prioritization Criterion | Description | Data Sources & Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Context | Prioritize hits in regulatory regions like promoters or enhancers, especially those with known chromatin marks. | ENSEMBL, UCSC Genome Browser, FANTOM5 Enhancer Atlas [8] |

| meQTL Overlap | Check if the CpG is a known meQTL. Colocalization with a GWAS signal can suggest a shared causal variant. | Public meQTL databases (e.g., MeQTL EPIC Database [12]), colocalization analysis |

| Gene Function & Pathway Enrichment | Prioritize genes involved in biological pathways relevant to your trait of interest. | GO, KEGG, WikiPathways, DAVID, g:Profiler [9] [8] |

| Evidence from Other Omics | Cross-reference with gene expression (eQTL) data or protein-protein interaction networks. | GTEx, expression databases, tools like MetaCore [13] |

| Previous Literature | Check for known associations of the gene with your trait or related phenotypes in biomedical literature. | PubMed, GWAS Catalog |

Q5: What are the common pitfalls when mapping EWAS hits to pathways, and how can I avoid them?

Common pitfalls and their solutions include:

- Pitfall: Incorrect gene mapping. Assigning a CpG to the nearest gene by base-pair distance alone can be misleading.

- Solution: Use a distance-to-TSS (Transcription Start Site) threshold (e.g., within 5-10 kb) and integrate functional genomic data like chromatin interaction maps (Hi-C) to find the true target gene [8].

- Pitfall: Ignoring cell type heterogeneity. Methylation patterns are cell-specific. EWAS on bulk tissue (like whole blood) can detect changes due to shifts in cell composition rather than intrinsic methylation.

- Solution: Perform statistical deconvolution to estimate and adjust for cell type proportions in your analysis [11].

- Pitfall: Using an outdated or biased pathway database.

- Solution: Select a well-curated, current pathway collection and consider using multiple pathway analysis tools to identify robust results [9].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Gene Mappings from Different Annotation Tools

- Issue: You have annotated your list of significant CpGs using two different pipelines (e.g., ChAMP and a custom script) and get slightly different gene lists.

- Explanation: This discrepancy arises from differences in the tools' underlying gene annotation databases (e.g., RefSeq vs. GENCODE) and the rules for assigning a CpG to a gene (e.g., distance to TSS, presence in a defined regulatory region).

- Solution:

- Standardize your input: Use a consistent gene annotation file (e.g., from GENCODE) across your analyses.

- Define a clear mapping rule: Decide on a specific strategy, for example: "Map a CpG to a gene if it is within the gene body or up to 5kb upstream of the TSS."

- Take the union and flag conflicts: For downstream analysis, consider taking the union of genes mapped by different reliable methods, but keep a record of which genes were identified by which tool. Genes mapped by multiple methods are higher confidence.

Problem: Low Statistical Power in Pathway Enrichment Analysis

- Issue: Your pathway analysis returns no significant results, even though your EWAS identified many DMPs.

- Explanation: Standard over-representation analysis (ORA) often fails when the per-gene evidence is moderate and spread across many pathways. It also relies on an arbitrary significance threshold for including genes.

- Solution:

- Use a competitive, rank-based method: Switch from ORA to a method like Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA). GSEA uses the full ranked list of genes (e.g., ranked by EWAS p-value) and does not require a strict significance cutoff, making it more powerful for detecting subtle but coordinated shifts in pathway activity [9].

- Use pathway topology-aware methods: Some advanced methods incorporate the structure of pathways (e.g., if your hits are concentrated on key pathway nodes), which can increase sensitivity [9].

- Check gene set size limits: Ensure you have not set overly restrictive limits on the size of gene sets to test. Very small sets are underpowered, while very large sets are non-specific [9].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Functional Enrichment Analysis for an EWAS Hit List

This protocol details the steps for a standard over-representation analysis (ORA) to identify biological pathways enriched among genes associated with your significant DMPs.

Methodology:

Input Preparation:

- Generate a gene list: From your EWAS results, extract all CpG sites that pass your significance threshold (e.g., FDR < 0.05). Map these CpGs to genes using a defined rule (see Troubleshooting Guide above). This is your "foreground" or "test" gene list.

- Define the background: This should be the set of all genes that were theoretically testable in your study, typically all genes that have at least one CpG site on the methylation array used. This is your "background" gene list.

Tool Selection & Execution:

Result Interpretation:

- The tool will output a table of enriched pathways with associated p-values and False Discovery Rate (FDR) corrections. Focus on terms with FDR < 0.05 or 0.01.

- Critically evaluate the results for biological plausibility in the context of your trait.

Protocol 2: Integration of EWAS Hits with meQTL Data

This protocol describes how to determine if the methylation level at your significant CpG site is influenced by genetic variation.

Methodology:

Data Requirements:

- Your EWAS results (CpG list and p-values).

- Genotype data (e.g., SNP array or whole-genome sequencing) for the same individuals used in the EWAS.

- Methylation beta or M-values for the same individuals.

Analysis Pipeline (using R/Bioconductor):

- Quality Control: Ensure both genotype and methylation data have undergone standard QC procedures.

- meQTL Analysis: Use a package like

MatrixEQTLormeQTLto perform a genome-wide scan. For each significant CpG from your EWAS, test for association between all SNPs within a 1 Mb window (cis-meQTL) and the methylation level of that CpG. - Multiple Testing Correction: Apply a multiple testing correction (e.g., Bonferroni or FDR) to identify significant SNP-CpG pairs.

Interpretation and Prioritization:

- A significant meQTL indicates that the methylation level is under partial genetic control.

- Colocalization Analysis: If a GWAS for your trait exists, perform a colocalization analysis (e.g., with

colocR package) to assess if the meQTL and the GWAS signal share the same causal variant [12]. This provides strong evidence for prioritization.

Signaling Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

EWAS Functional Follow-up Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Resources for Annotation and Prioritization of EWAS Hits

| Item / Resource | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Illumina Methylation Arrays (450K, EPIC) | The most widely used platform for generating epigenome-wide methylation data. The EPIC array covers over 850,000 CpG sites [11]. |

| Bioinformatic Pipelines (ChAMP, Minfi) | R-based packages for comprehensive quality control, normalization, and analysis of methylation array data, including DMP and DMR identification [11]. |

| ENSEMBL / UCSC Genome Browser | Public genomic databases used for annotating CpG sites with genomic features (e.g., gene name, distance to TSS, chromatin states). |

| meQTL Databases (e.g., MeQTL EPIC Database [12]) | Online repositories to check if your significant CpG sites are known to be regulated by genetic variants (meQTLs). |

| Pathway Analysis Tools (DAVID, g:Profiler, GSEA) | Software and web services for performing over-representation analysis (ORA) or gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) on your gene list [9]. |

| Pathway Visualization Tools (PathVisio, Cytoscape) | Software that allows for the visualization of genetic variants and other omics data on pathway diagrams to aid biological interpretation [9]. |

FAQs: Troubleshooting mQTL and Epigenomic Data Integration

FAQ 1: Why should I correct for mQTLs in my EWAS, and how much difference does it make? Genetic variants can significantly influence DNA methylation levels at specific CpG sites. Failing to account for mQTLs can introduce confounding or add noise to your association results. One study found that approximately 15-23% of CpGs on common methylation arrays are affected by mQTLs. Correcting for them can improve EWAS model fit and increase significance for true positive hits. For CpGs in genes related to specific traits like birthweight, accounting for mQTLs changed the regression coefficients by more than 20% compared to models that ignored genetic effects [14].

FAQ 2: I've found EWAS hits in blood. Are they relevant to brain-related traits? There is evidence of some cross-tissue conservation. Analyses have shown that for some CpG sites, DNA methylation variation in blood mirrors variation in the brain [15]. Furthermore, effects of genetic variants on nearby DNA methylation (cis-mQTLs) often correlate strongly between blood and brain cells [15]. However, this correlation is not universal, and tissue-specific effects are common. For brain-related traits, always consult databases that provide mQTL and methylation data from brain tissues when available.

FAQ 3: A large proportion of my EWAS top-hits are known smoking-associated CpGs. How should I proceed? This is a common issue, as exposure to cigarette smoke has a profound effect on the methylome. It is crucial to evaluate whether the smoking-associated methylation signal is a confounder or part of the biological pathway of your trait of interest. In a meta-analysis of aggression, for example, current and former smoking and BMI explained an average of 44% (range 3–82%) of the aggression-methylation association at specific top CpG sites [15]. You should:

- Carefully control for smoking status in your EWAS model where the data is available [15].

- Annotate your top hits against known databases of smoking-associated CpGs to assess the potential for confounding.

- Use sensitivity analyses to determine how your results change with the inclusion of smoking as a covariate.

FAQ 4: What is the best way to identify mQTLs for my dataset? The standard protocol involves performing a linear regression between each genotyped SNP and each CpG site's methylation level (typically within a cis-window, e.g., 1 Mb upstream and downstream of the CpG). Key steps include:

- Cohort-specific analysis: Run mQTL analysis in each cohort/ethnicity separately to account for population structure.

- Quality Control: Apply stringent QC to both genotype and methylation data. Remove CpG probes known to be affected by SNPs [14] [15].

- Meta-analysis: Combine results from multiple datasets using tools like METAL to increase power [14] [15].

- Multiple Testing Correction: Apply appropriate multiple testing corrections (e.g., Bonferroni or FDR) to identify significant CpG-SNP pairs [14].

FAQ 5: My EWAS and mQTL data are from different cohorts. How can I integrate them? You can use publicly available mQTL databases as a resource. For Illumina array data, you can annotate your significant CpG sites against these databases to check if they are known to be under genetic control. Large studies often publish their mQTL databases, which can be used as a look-up table. If you have genotype data for your cohort, you can directly test for mQTL effects. If not, using external mQTL databases still provides valuable biological context about the potential genetic influence on your EWAS findings [14].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Conducting an EWAS with mQTL Correction

This protocol outlines a standard workflow for an epigenome-wide association study that accounts for genetic confounding.

1. Pre-processing and Quality Control (QC) of Methylation Data

- Platform: Use Illumina Infinium Methylation arrays (450K or EPIC).

- QC Steps:

- Probe Filtering: Remove probes with a high detection p-value (>0.01), probes on sex chromosomes, cross-reactive probes, and probes containing SNPs at the CpG site or single base extension site [15] [1].

- Normalization: Use R packages like minfi or ChAMP to perform normalization (e.g., BMIQ, SWAN) to correct for technical variation between probe types [1].

- Cell Type Composition: Estimate white blood cell proportions (e.g., using the Houseman method) and include them as covariates in the model if using whole blood [1] [16].

2. Association Analysis

- Model: Use linear regression (for continuous traits) or logistic regression (for case-control studies). The basic model (Model 1) is:

Methylation β-value ~ Phenotype + Sex + Age + Technical Covariates + Cell Type Proportions

- Enhanced Model (Model 2): To account for key environmental confounders, extend the model:

Methylation β-value ~ Phenotype + Sex + Age + Technical Covariates + Cell Type Proportions + Smoking Status + BMI[15]

3. Integration of mQTL Information

- Covariate Approach: If you have genotype data, identify significant mQTLs (CpG-SNP pairs) and include the SNP genotypes as additional covariates in the EWAS model for those specific CpGs [14].

- Post-hoc Annotation: If you lack genotype data, annotate your top EWAS hits against published mQTL databases to assess whether they might be driven by genetic variation [14].

4. Multiple Testing Correction

- Apply a multiple testing correction to the results of the EWAS model. A common threshold for epigenome-wide significance is P < 1.2 × 10⁻⁷ (Bonferroni correction for ~450,000 tests) or a False Discovery Rate (FDR) of 5% [15] [1].

Protocol 2: Building a Cohort-Specific mQTL Database

1. Data Preparation

- Obtain matched genotype and methylation data for your cohort.

- Perform standard QC on both datasets independently.

2. Association Testing

- For each CpG site, test for association with all SNPs within a defined cis-window (e.g., 1 Mb on either side).

- Use a linear model:

Methylation β-value ~ SNP Genotype + Principal Components + Sex + Age + Cell Type Proportions.

3. Meta-Analysis

- If you have multiple cohorts, meta-analyze the cohort-level summary statistics using software like METAL to increase power and create a unified mQTL database [14] [15].

4. Database Generation

- For each CpG, record all significantly associated SNPs (after multiple testing correction), their effect sizes, and p-values. This collection forms your mQTL database [14].

Data Presentation

Table 1: mQTL Characteristics from Neonatal Blood Studies

This table summarizes key findings from a study investigating mQTLs in a multiethnic population of newborns, illustrating the scope of genetic influence on the methylome [14].

| Metric | 450K Array | EPIC Array | Notes / Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| CpGs with mQTLs | 15.4% | 23.0% | A substantial portion of the epigenome is under genetic influence; the EPIC array's higher yield is likely due to a larger sample size [14]. |

| Ethnicity Difference | Lower in NLW | Lower in NLW | Latino (LAT) cohorts had a higher proportion of mQTLs, attributed to their larger sample sizes within the study [14]. |

| Genomic Enrichment | CpG island shores | CpG island shores | mQTL-matched CpGs are significantly enriched in CpG island shore regions, which are key regulatory areas [14]. |

| Enrichment in TF Binding Sites | Less enriched | Less enriched | Transcription Factor (TF) binding sites are less likely to harbor mQTLs, suggesting core regulatory regions are buffered against genetic variation [14]. |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for EWAS/mQTL Analysis

A list of key software tools and databases crucial for conducting and interpreting EWAS and mQTL studies.

| Item Name | Function / Application | Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| ChAMP(R Package) | EWAS Data Analysis | A comprehensive pipeline for importing, quality controlling, normalizing, and analyzing Illumina Methylation array data; can identify DMPs and DMRs [17] [1]. |

| minfi(R Package) | EWAS Data Analysis | Another widely used R package for the analysis of Illumina methylation arrays, offering robust pre-processing and normalization methods [1]. |

| METAL(Software) | Meta-analysis | A tool for performing meta-analysis of genome-wide or epigenome-wide association summary statistics from multiple cohorts [14] [15]. |

| RnBeads(R Package) | EWAS Analysis | A tool for comprehensive analysis of DNA methylation data from various platforms, supporting advanced analyses like cell type composition and differential methylation [17]. |

| DMRcate(R Package) | DMR Identification | Identifies differentially methylated regions (DMRs) from Illumina array or whole-genome bisulfite sequencing data [17]. |

| eFORGE(Web Tool) | Functional Enrichment | An EWAS analysis tool that identifies tissue- or cell type-specific signals by analyzing overlaps with DNase I hypersensitive sites and transcription factor binding [17]. |

| Illumina 450K/EPIC Array(Platform) | Methylation Profiling | The standard microarrays for epigenome-wide association studies, measuring methylation at >450,000 or >850,000 CpG sites, respectively [1]. |

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: EWAS with mQTL Integration Workflow

Diagram 2: Functional Follow-up Strategy for EWAS Hits

A fundamental challenge in biomedical research, particularly in the functional follow-up of Epigenome-Wide Association Study (EWAS) hits, is distinguishing causal relationships from mere correlations. Observational studies often identify associations between molecular traits and disease, but these can be misleading due to confounding factors and reverse causation. Mendelian Randomization (MR) has emerged as a powerful methodological framework that addresses these limitations by leveraging genetic variants as instrumental variables to test causal hypotheses. This approach serves as a critical bridge between initial correlation findings from EWAS and establishing actionable causal evidence for downstream drug development.

MR is based on the principle that genetic variants are randomly assigned during gamete formation and conception, much like the randomization in a clinical trial [18] [19]. This natural randomization creates a study design that can provide unconfounded estimates of causal effect, helping researchers prioritize molecular targets with genuine causal evidence for disease outcomes. For researchers investigating EWAS hits, MR offers a methodological pathway to determine whether epigenetic changes likely influence disease, are consequences of disease processes, or simply share common causes.

Core Principles and Assumptions of Mendelian Randomization

The Genetic Instrument: Nature's Randomized Trial

Mendelian randomization uses genetic variants, typically single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), as instrumental variables for modifiable exposures [20]. These genetic instruments must satisfy three core assumptions:

- Relevance: The genetic variant must be robustly associated with the exposure of interest [20]

- Independence: The genetic variant must not be associated with confounders of the exposure-outcome relationship [20]

- Exclusion Restriction: The genetic variant must affect the outcome only through the exposure, not via alternative pathways (no horizontal pleiotropy) [20]

The following diagram illustrates the core MR design and its key assumptions:

Figure 1: Core Mendelian Randomization Design. The genetic instrument (G) must be associated with the exposure (E) but not share common causes with the outcome (O), nor affect the outcome through pathways other than the exposure.

Comparison with Other Study Designs

MR occupies a unique space in the evidence hierarchy between observational studies and randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The table below compares key characteristics:

| Study Design | Randomization Principle | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Observational Study | No randomization | Efficient for hypothesis generation; suitable for rare outcomes | Susceptible to confounding and reverse causation |

| Mendelian Randomization | Random allocation of genetic variants at conception | Reduces confounding and reverse causation; can assess lifelong exposure effects | Requires specific genetic assumptions; limited by pleiotropy |

| Randomized Controlled Trial | Active randomization of participants | Gold standard for causal inference; minimizes confounding | Expensive; time-consuming; may raise ethical concerns |

Table 1: Comparison of Study Designs for Causal Inference. MR bridges the gap between observational studies and RCTs, leveraging genetic variation as a natural experiment [18].

Implementing Mendelian Randomization: A Technical Guide

Experimental Workflow for MR Analysis

A typical MR analysis follows a structured workflow from study design through interpretation. The following diagram outlines key stages:

Figure 2: Mendelian Randomization Analysis Workflow. The process involves clearly defining the causal question, selecting appropriate genetic instruments, obtaining association estimates, performing statistical analyses, and carefully interpreting results.

MR analyses can be conducted using either individual-level or summary-level genetic data [19]. Summary-data MR has become increasingly popular with the availability of large-scale GWAS consortia data:

- Individual-level data: Contains genotype, exposure, and outcome data for each participant

- Summary-level data: Uses pre-calculated genetic association estimates from different studies (two-sample MR)

Selecting valid genetic instruments is a critical step. Instruments are typically chosen from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of the exposure, selecting variants that reach genome-wide significance (p < 5×10⁻⁸) [21]. For polygenic traits, multiple genetic variants can be combined into allele scores that collectively instrument the exposure [20].

Statistical Methods for MR Analysis

Several statistical approaches are available for MR analysis, each with different assumptions and applications:

| Method | Description | Key Assumptions | When to Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wald Ratio | Single variant estimate: βYX/βGX | Standard IV assumptions | Single instrument available |

| Inverse Variance Weighted (IVW) | Weighted average of ratio estimates | All variants are valid instruments | Multiple independent instruments |

| MR-Egger | Allows for pleiotropy via intercept term | Instrument Strength Independent of Direct Effect (InSIDE) | Suspected directional pleiotropy |

| Weighted Median | Provides consistent estimate if ≥50% valid | Majority of weight from valid instruments | Heterogeneous instrument effects |

Table 2: Common Statistical Methods for Mendelian Randomization Analysis. Method selection depends on the number of available instruments and assumptions about pleiotropy [20] [19].

The IVW method, the most common approach for multiple instruments, can be implemented using the formula:

βMR = Σ(βGYβGXσY⁻²) / Σ(βGX²σY⁻²)

Where βGX represents the genetic variant-exposure association, βGY represents the genetic variant-outcome association, and σY⁻² represents the inverse variance of the genetic variant-outcome association [20].

Troubleshooting Common Issues in Mendelian Randomization

FAQ: Addressing Methodological Challenges

Q1: How can I assess whether my genetic instruments are valid?

- Test for instrument strength using F-statistics (F > 10 indicates adequate strength)

- Assess balance of covariates across genetic instrument groups

- Use MR-Egger regression to test for directional pleiotropy

- Perform leave-one-out analyses to identify influential variants

Q2: What should I do when I suspect horizontal pleiotropy?

- Apply robust MR methods (MR-Egger, weighted median, MR-PRESSO)

- Use tissue-specific instruments where possible

- Perform sensitivity analyses excluding pleiotropic variants

- Consider multivariable MR to account for measured pleiotropic pathways

Q3: How can I address weak instrument bias?

- Use many weak instruments with methods robust to weak instrument bias

- Consider using summarized data from larger GWAS for exposure associations

- Apply methods specifically designed for many weak instruments

- Use family-based designs to eliminate confounding [19]

Q4: What are the options when working with limited sample sizes?

- Utilize two-sample MR with publicly available summary statistics

- Collaborate with consortia to access larger datasets

- Consider polygenic risk scores as instruments

- Use Bayesian methods that can provide more precise estimates with regularization

Q5: How can I distinguish causality from reverse causation?

- Perform bidirectional MR analyses

- Assess temporal relationships using prospective studies

- Use epigenetic age acceleration measures as exposures

- Consider family-based designs to reduce confounding [19]

Research Reagent Solutions for MR Studies

| Resource Type | Examples | Primary Function | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software Packages | TwoSampleMR, MR-Base, MendelianRandomization | Statistical analysis of MR data | CRAN, GitHub |

| GWAS Catalog | NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog | Source of genetic associations | https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/ |

| Summary Data Platforms | MR-Base, UK Biobank, GWAS ATLAS | Access to summary statistics | Platform-specific access |

| Quality Control Tools | PLINK, PRSice | Genotype data QC and analysis | https://www.cog-genomics.org/plink/ |

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Mendelian Randomization Studies. These tools and databases support various stages of MR analysis from data acquisition to statistical implementation [21] [22].

Advanced Applications in Functional Follow-up of EWAS Hits

Integrating MR with EWAS for Causal Inference

MR provides a powerful framework for prioritizing EWAS findings by testing whether epigenetic markers likely influence disease (causal), are consequences of disease (reverse causation), or are confounded by other factors [10] [8]. The following diagram illustrates how MR can be applied in the context of EWAS follow-up:

Figure 3: Integrating Mendelian Randomization in EWAS Follow-up. MR uses methylation quantitative trait loci (mQTLs) as instruments to test causal relationships between epigenetic markers and disease outcomes, helping distinguish causal effects from reverse causation and confounding [10].

Research comparing GWAS and EWAS findings has shown that these approaches often capture distinct biological aspects of complex traits [10]. For instance, a systematic comparison of 15 complex traits found substantial overlap between GWAS and EWAS only for diastolic blood pressure, suggesting that in most cases, these study designs identify different genes and biological pathways [10].

Multivariable and Bidirectional MR Applications

Advanced MR extensions can address more complex research questions:

- Multivariable MR: Assesses the direct effect of multiple related exposures

- Bidirectional MR: Tests for directional causality between two traits

- Network MR: Maps causal pathways between multiple interconnected traits

- Mediation MR: Decomposes total effects into direct and indirect effects

For drug development professionals, MR can provide critical evidence for target prioritization by establishing whether proteins or epigenetic markers likely play causal roles in disease pathogenesis [19]. This application has gained traction in pharmaceutical research, with MR analyses increasingly informing target validation decisions.

Mendelian randomization represents a powerful methodological approach for strengthening causal inference in the functional follow-up of EWAS hits. By leveraging the natural randomization of genetic variation, MR helps address fundamental challenges of confounding and reverse causation that plague observational studies. While methodological challenges remain, particularly regarding instrument validity and pleiotropy, ongoing methodological developments continue to enhance the robustness of MR applications.

For researchers and drug development professionals, MR provides a valuable tool for prioritizing molecular targets with genuine causal evidence for disease outcomes. When carefully applied and interpreted with appropriate sensitivity analyses, MR can significantly strengthen the evidence base translating correlational findings from EWAS into actionable insights for therapeutic development.

A Practical Pipeline: From Data Analysis to Functional Hypothesis Generation

Troubleshooting Common Pipeline Errors

This section addresses frequent issues encountered when running the ChAMP and Minfi pipelines for epigenome-wide association studies (EWAS).

ChAMP-Specific Issues and Solutions

Q1: What does the error "Error Match between pd file and Green Channel IDAT file" mean and how do I resolve it?

This error occurs when ChAMP cannot properly match your sample sheet (phenotypic data or "pd" file) with the IDAT files in your directory [23].

Solution: Follow this systematic checklist:

- Verify Column Headers: Ensure your sample sheet contains the exact column headers required by ChAMP. Critical columns include

Slide,Array, andBasename[23]. - Check Sentrix ID Format: Confirm that Sentrix IDs in your sample sheet match exactly with those in your IDAT filenames. Even minor formatting discrepancies can cause this error [23].

- Validate File Paths: If using explicit paths in your

Basenamecolumn, ensure they are correct and accessible from your R working directory. - Confirm Array Type: Explicitly specify your array type (

arraytype = "EPIC"orarraytype = "450K") in thechamp.import()function call.

Q2: Why does my normalization fail with "internet routines cannot be loaded" or similar errors?

This error often occurs during the champ.norm() step, particularly when using parallel processing functions [24].

Solution:

- Check Parallel Processing Configuration: Reduce the number of cores specified in the

coresparameter. Start withcores = 1to test if the error persists. - Verify R Installation: Ensure your R installation can create socket connections for parallel processing. Reinstall R or relevant packages (

parallel,snow) if necessary. - Alternative Normalization: Try a different normalization method. If

BMIQfails, attemptSWANorPBCmethods instead [24].

Q3: Why does FunctionalNormalization fail with "subscript out of bounds" on EPIC data?

This error may occur due to annotation package mismatches when running champ.norm() with method = "FunctionalNormalization" on EPIC data [25].

Solution:

- Annotation Consistency: ChAMP typically installs

IlluminaHumanMethylationEPICanno.ilm10b2.hg19automatically, but FunctionalNormalization may requireIlluminaHumanMethylationEPICanno.ilm10b3.hg19[25]. - Manual Installation: Manually install the required annotation package:

- Alternative Method: Consider using

ssNoobnormalization instead, as FunctionalNormalization may not significantly enhance results overssNoobfor EPIC arrays [25].

Minfi-Specific Issues and Solutions

Q4: Why are my annotation and manifest listed as "unknown" after using read.metharray.exp?

This issue occurs when Minfi cannot properly load the required annotation packages, despite them being installed [26].

Solution:

- Explicitly Load Annotations: Manually load the required annotation packages before running your analysis:

- Check Package Versions: Ensure compatibility between Minfi, annotation packages, and your R version. Consider updating all packages to the latest versions.

- Verify Installation: Confirm annotation packages are installed correctly for your specific array type (EPIC vs. 450K).

Q5: Why does preprocessRaw fail with "there is no package called 'Unknownmanifest'"?

This error directly relates to the previous issue where annotations are not properly loaded [26].

Solution:

- Reinstall Packages: Reinstall both Minfi and relevant annotation packages using BiocManager to ensure compatibility.

- Session Restart: Restart your R session and reload all required packages before reprocessing your data.

- Explicit Manifest Specification: When creating RGChannelSet objects, explicitly specify the manifest when possible.

General Pipeline Issues

Q6: How do I choose between ChAMP and Minfi for my EWAS?

Both pipelines offer comprehensive analysis capabilities, but have different strengths:

Table: Comparison of ChAMP and Minfi Pipelines

| Feature | ChAMP | Minfi |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Use Case | All-in-one solution for EPIC data [11] | Most cited for 450K data [11] |

| Data Import | Direct from IDAT files [11] | Direct from IDAT files [11] |

| Quality Control | Integrated in pipeline [11] | Integrated in pipeline [11] |

| Normalization | Multiple methods (BMIQ, SWAN, FunctionalNormalization) [24] [25] | Multiple methods [11] |

| DMP Detection | Yes [11] | Yes [11] |

| DMR Detection | Yes [11] | Yes [11] |

| Downstream Analyses | Variety available [11] | Variety available [11] |

Q7: What alternative normalization methods exist when standard approaches fail?

If standard normalization methods consistently fail, consider:

- Method Rotation: Try different normalization techniques. ChAMP supports BMIQ, SWAN, PBC, and FunctionalNormalization [24] [25].

- Quality Assessment: Check if normalization fails due to poor sample quality. BMIQ may fail for samples "that did not even show beta distribution" [24].

- Alternative Pipeline: Explore the

sesamepackage, which shows excellent performance on diverse datasets including TARGET and TCGA, though not yet integrated directly into ChAMP [25].

Methodological Framework for EWAS Follow-up

This section provides experimental protocols and methodologies for functional follow-up of EWAS hits within the context of broader research strategies.

EWAS Experimental Design Considerations

Proper experimental design is critical for meaningful EWAS results and downstream functional validation.

Table: EWAS Study Designs for Functional Follow-up

| Design Type | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case-Control | Compares unrelated cases vs. controls [11] [8] | Large sample sizes possible; utilizes existing biobanks [11] | Cannot determine causality; timing of methylation changes unknown [11] | Initial association discovery; leveraging existing DNA banks [11] |

| Longitudinal | Tracks same individuals over time [11] [8] | Establishes temporal relationships; tracks methylome dynamics [11] | Time-consuming; expensive; pre-disease samples difficult to obtain [11] | Establishing causality; natural history studies; intervention studies [11] |

| Monozygotic Twin Studies | Compares genetically identical twins discordant for disease [8] | Controls for genetic variation; powerful for epigenetic studies [8] | Difficult to recruit large cohorts; cannot determine timing without longitudinal data [8] | Isolating non-genetic components of disease [8] |

| Family Studies | Examines transgenerational inheritance patterns [8] | Can rule out genomic variation effects [8] | Few large cohorts available [8] | Studying transgenerational epigenetic inheritance [8] |

The following diagram illustrates the strategic decision process for selecting appropriate EWAS designs:

Advanced Analytical Approaches for EWAS Follow-up

Methylation Quantitative Trait Loci (methQTL) Analysis: This analysis identifies genetic variants that influence methylation states, helping to determine whether observed methylation changes are driven by genetic variation or environmental factors [11]. MethQTL analysis integrates SNP and methylation data to discover loci where genotype correlates with methylation phenotype, distinguishing primary epigenetic changes from those secondary to genetic variation [27].

Cell-Type Deconvolution: For blood-based EWAS, statistical deconvolution methods estimate cell-type specific methylation signals from mixed cell population data [11]. This is crucial as cellular heterogeneity can confound methylation associations, particularly in whole blood samples where multiple cell types contribute to the methylation signal.

Methylation Age Analysis: The epigenetic clock provides a biological age estimate based on methylation patterns at specific CpG sites [11]. Discrepancies between epigenetic age and chronological age can indicate accelerated aging or disease states, providing functional context for EWAS hits.

Research Reagent Solutions for EWAS

Table: Essential Research Materials for EWAS and Functional Follow-up

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application in EWAS |

|---|---|---|

| Illumina Methylation BeadChips | Genome-wide methylation profiling | Primary data generation for EWAS (27K, 450K, EPIC arrays) [11] [8] |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits | Chemical treatment of DNA for methylation detection | Distinguishes methylated vs unmethylated cytosines prior to array analysis [11] |

| Annotation Packages (e.g., IlluminaHumanMethylationEPICanno.ilm10b4.hg19) | Provide genomic context for CpG probes | Essential for mapping CpG sites to genes and regulatory regions during analysis [26] |

| Cell-Type Specific Reference Methylomes | Reference datasets for deconvolution algorithms | Enable estimation of cell-type proportions in mixed samples (e.g., whole blood) [11] |

| Functional Normalization Components | Remove technical variation using control probes | Normalization to improve data quality and reduce false positives [25] |

Workflow Integration and Best Practices

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive EWAS workflow incorporating both ChAMP/Minfi analysis and functional follow-up strategies:

Integration with Genomic Data

For comprehensive functional follow-up, integrate EWAS results with complementary genomic datasets:

- GWAS Integration: Combine significant EWAS hits with existing GWAS data to dissect complex haplotypes and identify potentially functional variants [28] [27].

- Expression QTL (eQTL) Mapping: Correlate methylation quantitative trait loci with expression quantitative trait loci to understand the functional consequences of methylation changes.

- Multi-omics Approaches: Incorporate proteomic, metabolomic, or other epigenomic data (e.g., histone modifications) to build comprehensive models of disease pathophysiology.

By addressing both technical pipeline challenges and methodological framework for functional follow-up, this guide provides researchers with comprehensive tools for conducting robust EWAS and deriving biologically meaningful insights from methylation data.

Fundamental Concepts FAQ

What is a methylation quantitative trait locus (methQTL) and why is it important for functional follow-up in EWAS?

A methylation quantitative trait locus (methQTL) is a region of the genome where genetic variants (such as single nucleotide polymorphisms or SNPs) are associated with variation in DNA methylation states at specific CpG sites [29]. These associations can range from a few bases to several megabases, potentially resulting in long-range interactions [29]. MethQTLs are crucial for annotating the functional effects of genetic variants discovered in EWAS and help distinguish variants that are merely correlated with disease from those that are functionally involved [30]. They provide a direct link between genetic predisposition and epigenomic regulation, illuminating the mechanistic pathway from genotype to phenotype.

What is the difference between cis- and trans-meQTLs?

- cis-meQTLs are genetic variants that influence DNA methylation at loci located relatively close to the variant, typically within 500 kb to 2 Mb [29] [30].

- trans-meQTLs are genetic variants that affect DNA methylation at loci located far away on the same chromosome or on a different chromosome [30]. These can form complex regulatory networks, such as the ERG-mediated network of 233 trans-methylated CpGs involved in hematopoietic cell differentiation [31].

What is Methylation Age (Epigenetic Clock) and how does it relate to biological aging?

The Methylation Age or Epigenetic Clock is a highly accurate age predictor based on the systematic changes in DNA methylation patterns at specific CpG sites throughout an individual's life [32]. It is calibrated using machine learning models on large-scale methylation datasets. Epigenetic Age Acceleration (EAA) refers to the deviation between DNA methylation-predicted age and chronological age. Positive EAA (where the epigenetic age is older than chronological age) reflects accelerated biological aging and is a significant predictor of health outcomes, including a 16% increased risk of stroke per unit increase in EAA (OR = 1.16, 95% CI 1.13–1.19) [33]. This acceleration is thought to reflect pathophysiological processes like organ functional decline and inflammatory activation [33].

What are the different types of QTLs relevant for multi-omics integration?

QTL analysis has expanded to cover various molecular layers, providing a network view of how variants influence phenotype [30].

- eQTL: Affects gene expression levels.

- meQTL/methQTL: Affects DNA methylation patterns.

- caQTL: Affects chromatin accessibility.

- bQTL: Affects transcription factor binding.

- pQTL: Affects protein abundance.

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Common MethQTL Analysis Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions & Verification Steps |

|---|---|---|

| No significant meQTLs detected | Insufficient statistical power (small sample size), overly stringent multiple-testing correction, poor-quality methylation/genotype data, cell-type heterogeneity masking effects. | Increase sample size (100s of samples recommended). Use permutation-based FDR control (e.g., via fastQTL). Check data quality: ensure high call rates for SNPs/CpGs, inspect beta value distributions. Account for cell type composition in statistical models [29] [31]. |

| Inability to replicate meQTLs in an independent cohort | Differences in ancestry (presence of ancestry-specific meQTLs), differences in tissue/cell type composition, technical batch effects from different methylation platforms. | Use genetically similar cohorts for replication. Prefer profiling purified cell types over heterogeneous tissues. Harmonize processing pipelines and correct for batch effects. Check for EA-specific mQTLs if working with East Asian populations [31]. |

| Confounding by cell type heterogeneity | Methylation levels are highly cell-type-specific. If cell type proportions vary between samples and are not accounted for, they can create false positives or mask true meQTL signals. | Estimate cell type proportions using reference-based (e.g., Houseman method) or reference-free algorithms. Include these proportions as covariates in the meQTL mapping model. Use pipelines like MAGAR that are designed for multi-tissue/cell-type analysis [29]. |

| Computational challenges in processing WGBS data | WGBS data is computationally intensive to align and analyze, requiring specialized tools and significant memory/CPU resources. | Use established, efficient pipelines like msPIPE or Methy-Pipe [34] [35]. These pipelines integrate all steps from alignment to DMR calling and visualization, and can be run via Docker for easier implementation. |

Table 2: Common Methylation Age Analysis Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions & Verification Steps |

|---|---|---|

| Poor age prediction accuracy (high MAE) | Using an inappropriate epigenetic clock model (e.g., a blood clock on brain tissue), poor-quality methylation data, data from an unsupported species or tissue, incorrect model calibration. | Use a tissue-appropriate clock (e.g., Horvath's multi-tissue clock, Hannum's blood clock, PhenoAge). Ensure high data quality and that your data preprocessing matches the clock's requirements. For high accuracy in blood, consider non-linear, cohort-based models like GP-age [36]. |

| Inconsistent age acceleration values | Different clocks capture different aspects of biological aging. An individual might show acceleration on one clock but not another. | Clearly define the chosen clock and its biological interpretation (e.g., PhenoAge for morbidity/mortality). Report results consistently with the same clock across a study. Use multiple clocks only if hypothesizing different aging aspects. |

| Interpreting the biological meaning of EAA | EAA is a composite measure and does not point to a specific biological pathway or mechanism. | Correlate EAA with specific health phenotypes (e.g., stroke risk [33]). Perform downstream analyses like GO and KEGG enrichment on the CpG sites most weighted in the clock or those that deviate most from expected methylation levels [32]. |

| Feature selection for custom clock development | Using all CpG sites from a platform (e.g., 450K) is computationally intensive and can lead to overfitting. | Apply machine learning-based feature selection. For example, use gradient-boosting models (XGBoost, LightGBM, CatBoost) to identify a compact set of highly predictive CpG sites. As few as 30 CpG sites can achieve high accuracy in blood [32] [36]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Identifying methQTLs using the MAGAR Pipeline

Objective: To identify genetic variants that influence DNA methylation levels, distinguishing common from cell type-specific effects.

Materials:

- Matched genotyping (e.g., SNP array or WGS) and DNA methylation data (e.g., array or WGBS) from the same individuals.

- Software: MAGAR R package (available via Bioconductor) [29].

Method:

- Data Preprocessing: Process raw genotype and methylation data (IDAT files) using MAGAR's integrated modules, which leverage established tools like RnBeads, PLINK, and CRLMM for quality control and filtering [29].

- CpG Clustering: Group neighboring, highly correlated CpGs into "correlation blocks" to reduce redundancy and account for the correlation structure of methylation haplotypes [29].

- Tag-CpG Selection: For each correlation block, select a single representative "tag-CpG" for association testing [29].

- methQTL Calling: Test for associations between each tag-CpG and all SNPs within a defined genomic window (e.g., 500 kb upstream and downstream). This can be performed using:

- Linear Modeling: A standard linear least-squares regression.

- fastQTL: A permutation-based approach to control for multiple testing [29].

- Colocalization Analysis: Use the output from MAGAR to perform colocalization analysis across different tissues or cell types to define tissue-specific and tissue-independent (common) methQTLs [29].

Protocol 2: Constructing a Methylation Age Prediction Model

Objective: To build a machine learning model that predicts biological age from DNA methylation data.

Materials:

- A large dataset of DNA methylation samples (e.g., from a public repository like GEO) with known chronological ages. The example below uses 8,233 samples with 50,000 methylation sites each [32].

- Software: Python/R with machine learning libraries (e.g., XGBoost, LightGBM, CatBoost, SHAP).

Method:

- Data Preprocessing: Handle missing data (e.g., imputation or filling with 0). Encode categorical variables (e.g., sex). Perform quality control to remove low-quality probes [32].

- Feature Selection: To avoid overfitting and identify the most age-predictive CpGs, use a wrapper method with multiple machine learning models.

- Model Training: Train a final predictive model (e.g., Gradient Boosting) using the selected subset of features. Use k-fold cross-validation to optimize hyperparameters.

- Model Interpretation: Use interpretable ML frameworks like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) to determine the contribution of each CpG site to the final prediction. This helps identify key loci like cg23995914, which has been highlighted as a major contributor [32].

- Biological Validation: Perform functional enrichment analysis (GO, KEGG) on the genes associated with the top predictive CpG sites to understand the biological pathways underlying the aging signal [32].

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Pipelines

| Tool Name | Function | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| MAGAR [29] | methQTL identification | Discriminates cell type-specific effects by clustering correlated CpGs. |

| msPIPE [34] | WGBS Data Analysis | End-to-end pipeline from pre-processing to DMR calling and publication-quality visualization. Supports Docker. |

| Methy-Pipe [35] | WGBS Data Analysis | Integrated pipeline for bisulfite read alignment (BSAligner) and differential methylation analysis (BSAnalyzer). |

| fastQTL / MatrixEQTL [29] [31] | QTL Mapping | Fast, permutation-based tools for cis-QTL mapping. |

| GP-age [36] | Methylation Age Prediction | Non-linear, cohort-based clock using only 30 CpG sites for accurate blood age prediction. |

| SHAP [32] | Model Interpretation | Explains the output of any machine learning model, identifying key predictive CpG sites. |

Table 4: Key Methylation Clocks and Their Applications

| Clock Name | Tissues | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Horvath's Clock [33] | Multi-tissue | The first pan-tissue clock; useful for comparing aging rates across different tissues. |

| Hannum's Clock [33] | Blood | Predictive of age-related phenotypes and mortality risk in blood-based studies. |

| PhenoAge [33] | Blood | Captures physiological dysregulation and is a strong predictor of morbidity and mortality. |

| GP-age [36] | Blood | Compact, accurate clock for blood; ideal for longitudinal studies and forensic profiling. |

Epigenome-wide association studies (EWAS) investigating DNA methylation in easily accessible tissues like whole blood face a fundamental challenge: cellular heterogeneity. Blood is a complex mixture of different cell types, each with a distinct DNA methylation profile. When analyzing a bulk tissue sample, an observed DNA methylation difference could represent either a genuine change within a specific cell type or a mere shift in the cell type proportions between compared groups. Failing to account for this cellular composition is a major source of confounding and misinterpretation in EWAS [37] [38].

Statistical cell mixture deconvolution (CMD) has emerged as a powerful bioinformatic solution to this problem. These methods leverage pre-defined libraries of cell-type-specific DNA methylation markers to computationally estimate the proportional composition of cell types within a heterogeneous sample. These estimates can then be included as covariates in statistical models to control for confounding, allowing researchers to identify cell-type-specific epigenetic changes [38]. This guide addresses frequent questions and troubleshooting issues encountered when implementing these critical methods.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: What is the core problem that cellular deconvolution solves?

Answer: The core problem is confounding due to cellular heterogeneity. In a whole blood EWAS, if a disease state is associated with an increase in the proportion of neutrophils, and neutrophils have a characteristically low methylation at a particular CpG site, that site will appear to be hypomethylated in the disease group. This association is not driven by the disease process within a cell, but by a change in the underlying cell population. Deconvolution methods control for this by estimating and adjusting for these cell proportion shifts [37] [38].

FAQ 2: My deconvolution results show poor discrimination between certain cell types. What could be wrong?

Answer: Poor discrimination often stems from a suboptimal library of cell-specific methylation markers. The accuracy of deconvolution is entirely dependent on the quality of the reference library used. Libraries assembled using different criteria (e.g., top ANOVA hits vs. an equal number of markers per cell type) can have vastly different performances [38].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Evaluate Your Library: Investigate the library's composition. Some older libraries may over-represent markers that discriminate major lineages (e.g., myeloid vs. lymphoid) but perform poorly on lineage-specific subtypes (e.g., CD4+ T-cells vs. CD8+ T-cells) [38].

- Use an Optimized Library: Consider using a dynamically identified, optimized library. For example, the IDOL algorithm identified a 300-CpG library that demonstrated superior overall discrimination of the leukocyte landscape compared to earlier libraries, leading to more accurate cell fraction estimates and improved control of false positives in EWAS [38].

- Check Data Preprocessing: Ensure your DNA methylation data has been properly normalized, especially for the technical differences between Infinium I and Infinium II probe designs on the 450K/EPIC arrays. Methods like BMIQ (Beta Mixture Quantile dilation) are specifically designed to correct this probe type bias [39] [40].

FAQ 3: After deconvolution and adjustment, how do I interpret a significant EWAS hit?

Answer: A significant association after adjusting for estimated cell proportions suggests the DNA methylation change is independent of shifts in the major cell populations. However, precise interpretation requires further investigation:

- Cell-Type-Specific Effects: The association could be present in one, several, or all cell types. To determine this, you need to apply methods designed to identify cell-type-specific differential methylation (DMCTs), such as CellDMC [41]. For instance, a meta-analysis of smoking EWAS found that most smoking-associated hypomethylation was highly specific to cells of the myeloid lineage, a finding that would have been masked in a standard whole-blood analysis [41].

- Biological Context: The gene or region's known biology should be considered alongside the cell-type-specificity of the signal to generate meaningful hypotheses.

FAQ 4: How does cellular deconvolution impact the overlap between GWAS and EWAS findings?

Answer: GWAS and EWAS often identify distinct genomic regions and biological pathways for the same complex trait. Proper cellular deconvolution is critical for ensuring that EWAS signals reflect true intra-cellular epigenetic states rather than confounding by cell composition. When this confounding is controlled for, the remaining EWAS hits are less likely to be tagged by GWAS variants, as the two study designs are capturing different biological mechanisms—genetic predisposition versus environmentally responsive or consequential epigenetic regulation [42].

Essential Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Cellular Deconvolution Experiments

| Tool/Reagent Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| IDOL Algorithm [38] | Algorithm & Library | Identifies Optimal L-DMR libraries for deconvolution; provides an optimized 300-CpG library for whole blood. | Designed to maximize accuracy of cell fraction estimates; improves discrimination of lineage-specific cell subtypes. |

| CellDMC Algorithm [41] | Software Algorithm | Identifies cell-type-specific differential methylation from bulk tissue data. | Requires a pre-estimated cell composition as input; uses interaction terms in a linear model. |

| EpiDISH Algorithm [41] | Software Algorithm / Reference | A reference-based method for estimating cell composition from bulk DNA methylation data. | Provides a DNAm reference matrix for seven blood cell subtypes; often used in conjunction with CellDMC. |

| BMIQ [39] [40] | Normalization Method | Corrects for the technical bias between Infinium I and Infinium II probe designs. | Critical preprocessing step; improves data quality and comparability before deconvolution. |

| minfi / waterRmelon [39] [40] | R Packages | Comprehensive toolkits for importing, quality controlling, and normalizing Illumina methylation array data. | Include functions for performing cell mixture deconvolution (minfi) and various normalization schemes (waterRmelon). |

Experimental Workflow for Cell-Type Deconvolution

The following diagram illustrates the standard analytical workflow for conducting an EWAS that properly accounts for cellular heterogeneity, from raw data to biological interpretation.

Advanced Analysis: Protocol for Cell-Type-Specific Inference

For researchers who have identified significant EWAS hits after adjusting for cell proportions, the next logical step is to determine in which specific cell type the effect resides. The following protocol outlines this process using the CellDMC algorithm.

Objective: To identify cell-type-specific differential methylation (DMCTs) from bulk whole blood DNA methylation data.

Primary Software: R statistical environment.

Key R Packages: CellDMC, EpiDISH (or other packages that provide the necessary reference data and functions).

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Data Preparation and Preprocessing:

- Import your beta-value matrix (samples as columns, CpGs as rows) after it has undergone rigorous quality control and normalization [40]. Ensure you have applied a probe bias correction method like BMIQ.

- Prepare your phenotype file, encoding your exposure or trait of interest appropriately (e.g., 0=control, 1=case).

Estimate Cell Type Proportions:

- Use a reference-based method like

EpiDISHto estimate the proportions of major leukocyte subtypes (e.g., neutrophils, monocytes, B-cells, T-cells, NK-cells) in each sample. This will produce a matrix of estimated cell fractions. - Code Example:

- Use a reference-based method like

Run CellDMC Analysis:

- Execute the

CellDMCfunction, providing your normalized beta-value matrix, the phenotype vector, and the matrix of estimated cell fractions. - CellDMC fits a linear model that includes an interaction term between the phenotype and each cell type's fraction. A significant interaction term for a specific CpG and cell type indicates a DMCT.

- Code Example:

- Execute the

Interpretation of Results:

- The output will include, for each CpG site, p-values for the main effect of the phenotype and for the interaction with each cell type.

- Focus on CpGs with a significant interaction p-value (after multiple testing correction) for a specific cell type. This indicates that the association between the phenotype and DNA methylation is different in that cell type. The meta-analysis on smoking, for example, used this approach to pinpoint a hypomethylation signature predominantly in the myeloid lineage [41].

- Follow up on these cell-type-specific hits with functional annotation and pathway analysis to understand their potential biological relevance.

Epigenome-wide association studies (EWAS) systematically identify epigenetic marks, such as DNA methylation, associated with specific phenotypes or diseases [8]. The core challenge in functional genomics lies in moving from merely identifying these statistical associations to understanding their biological significance and mechanistic role in disease etiology [43]. Multi-omics integration provides a powerful framework for this functional follow-up by correlating methylation changes with downstream molecular consequences captured by transcriptomic (gene expression) and proteomic (protein abundance) data [44] [45].

This approach is pivotal because DNA methylation in promoter or regulatory regions can directly influence gene activity, potentially silencing or activating genes without changing the underlying DNA sequence [46] [47]. However, not all methylation changes are functionally consequential. By integrating data across omics layers, researchers can prioritize methylation hits that are associated with changes in gene expression or protein function, thereby distinguishing passenger events from driver events in disease processes [44] [48]. This technical support center is designed to guide you through the experimental and computational methodologies for successful multi-omics integration, directly addressing common pitfalls and providing actionable troubleshooting advice.

Key Concepts and Workflow

Fundamental Principles

- DNA Methylation: An epigenetic mark involving the addition of a methyl group to a cytosine base, typically within a CpG dinucleotide context. Hypermethylation in gene promoter regions is often associated with gene silencing, while hypomethylation can permit gene expression [46] [8].

- Quantitative Trait Loci (QTL) Mapping: A foundational analytical framework for multi-omics integration. This approach treats epigenetic marks as potential regulators and tests their association with molecular phenotypes:

- methylation QTL (mQTL): Genetic loci that influence methylation levels.

- expression QTL (eQTL): Loci that influence gene expression levels.

- protein QTL (pQTL): Loci that influence protein abundance [44].