EWAS Design and Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Epigenome-Wide Association Study (EWAS) design and analysis, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

EWAS Design and Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Epigenome-Wide Association Study (EWAS) design and analysis, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers foundational epigenetic principles and the role of DNA methylation in complex disease etiology. The guide details methodological workflows from sample preparation to data analysis using pipelines like ChAMP and Minfi, alongside practical applications across various disease contexts. It addresses common challenges including confounding factors, cell-type heterogeneity, and statistical power, offering proven optimization strategies. Finally, it explores validation techniques, comparative analyses with GWAS, and the critical issue of diversity in epigenomic research, synthesizing key takeaways and future directions for clinical translation.

The Foundations of EWAS: Unraveling the Epigenome's Role in Complex Disease

Epigenome-wide association studies (EWAS) represent a powerful methodological approach in functional genomics, designed to systematically investigate the association between epigenetic variants and phenotypic traits across the genome [1]. Similar in concept to genome-wide association studies (GWAS), EWAS specifically aims to identify epigenetic markers, most commonly DNA methylation variations, that are associated with diseases, environmental exposures, or other complex traits [2]. The primary significance of EWAS lies in its ability to explore the biological interface where genetic predisposition and environmental factors interact, providing mechanistic insights into disease pathophysiology that cannot be fully explained by genetic variation alone [1] [2]. Over the past decade, EWAS has evolved into a mature field with established protocols and has contributed substantially to our understanding of complex diseases, including cardiovascular disorders, cancer, and metabolic conditions [1] [3].

The fundamental rationale for EWAS stems from the dynamic nature of the epigenome, which serves as a molecular record of both genetic influences and environmental exposures [4]. DNA methylation, the most extensively studied epigenetic mark in EWAS, involves the covalent addition of a methyl group to cytosine bases in CpG dinucleotides, which can regulate gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence [1] [2]. This epigenetic mark exhibits chemical and temporal stability while remaining responsive to environmental influences, making it an ideal biomarker for investigating gene-environment interactions in complex diseases [1].

Key Technological Platforms for EWAS

The advancement of EWAS has been propelled by developments in high-throughput technologies for epigenome profiling. The following table summarizes the primary platforms used in contemporary EWAS research:

Table 1: Primary Technological Platforms for EWAS

| Platform Type | Specific Examples | CpG Coverage | Key Features and Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microarray-Based | Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation27 (27k) | 27,578 CpG sites | Early EWAS applications; covers 14,495 genes [1] [2] |

| Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 (450k) | 485,000 CpG sites | Most widely used platform; covers CpG islands, promoters, gene bodies [1] [2] | |

| Illumina Infinium MethylationEPIC (EPIC) | 850,000+ CpG sites | Expanded coverage including enhancer regions; current standard [1] [2] | |

| Sequencing-Based | Whole Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) | ~28 million CpG sites | Comprehensive methylation mapping; gold standard but cost-prohibitive for large studies [1] |

| Third-Generation Sequencing (SMRT) | Genome-wide | Direct detection without bisulfite conversion; uses polymerase kinetics [1] |

The measurement of methylation levels in microarray-based methods typically employs the beta value (β), calculated as β = M / (M + U + α), where M represents methylated intensity, U represents unmethylated intensity, and α is a constant offset (usually 100 for Illumina platforms) [1]. Beta values range from 0 (completely unmethylated) to 1 (completely methylated), with values ≥0.75 considered fully methylated and values ≤0.25 considered fully unmethylated [1].

Analytical Frameworks and Bioinformatics Tools

Robust bioinformatics pipelines are essential for EWAS data analysis, which involves multiple processing and normalization steps to account for technical variability and confounding factors. The following workflow outlines the core analytical process in a typical EWAS:

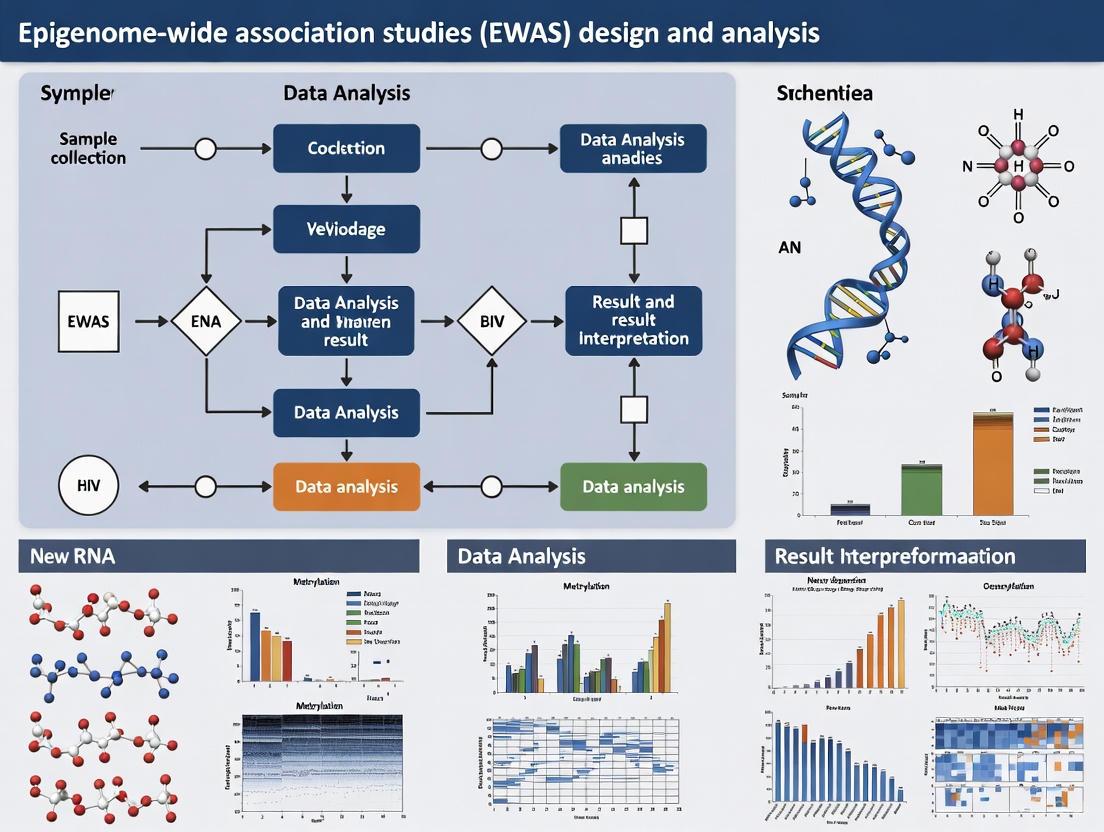

Figure 1: Core Workflow for EWAS Data Analysis

Two primary bioinformatics packages have emerged as standards for EWAS analysis: Minfi and Chip Analysis Methylation Pipeline (ChAMP) [2]. Both packages support the entire analytical workflow from raw data import to identification of differentially methylated positions (DMPs) and regions (DMRs), with ChAMP becoming increasingly prominent for EPIC array data analysis [2]. Additional specialized analyses often integrated into EWAS include:

- Methylation Quantitative Trait Loci (methQTL) analysis: Identifies genetic variants that influence methylation patterns [2]

- Statistical deconvolution methods: Estimates cell-type specific methylation from heterogeneous tissue samples [2]

- Methylation age analysis: Evaluates epigenetic clocks as biomarkers of biological aging [2]

- Mendelian Randomization: Provides causal inference between methylation and disease outcomes [3]

Table 2: Key Bioinformatics Tools for EWAS Analysis

| Tool/Package | Primary Function | Compatible Platforms | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minfi | Data preprocessing and analysis | 450K, EPIC | Most cited for 450K data; comprehensive quality control and normalization [2] |

| ChAMP | Integrated analysis pipeline | 450K, EPIC | Growing popularity for EPIC data; combines multiple analysis steps [2] |

| MEFFIL | Quality control and normalization | 450K, EPIC | Functional normalization; cell type composition estimation [5] |

| WaterRmelon | Preprocessing and analysis | 450K, EPIC | BMIQ normalization for probe-type bias correction [4] [5] |

Research Reagent Solutions for EWAS

Successful execution of EWAS requires specific research reagents and materials throughout the experimental workflow. The following table outlines essential solutions and their applications:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for EWAS Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits (e.g., EZ-96 DNA Methylation Kit) | Chemical treatment that converts unmethylated cytosines to uracil while methylated cytosines remain unchanged [4] [5] | Conversion efficiency must be verified; over-treatment can degrade DNA [1] |

| Infinium Methylation BeadChips (27K, 450K, EPIC) | Genome-wide methylation profiling using probe hybridization [1] [2] | Platform selection depends on coverage needs and budget; EPIC recommended for enhancer regions [1] |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality genomic DNA from biological samples | Yield and purity critical; salting-out protocols commonly used [5] |

| Cell Type Composition Reference Panels | Reference-based estimation of cellular heterogeneity in blood samples [2] [4] | Essential for blood-based EWAS; implemented in Houseman's method [4] [5] |

| Normalization Controls | Technical variation adjustment during data processing | Included in platforms or added during analysis (e.g., NOOB, BMIQ) [4] [5] |

Experimental Design Considerations

EWAS can be implemented through various study designs, each with distinct advantages and limitations. The most common approaches include:

Case-Control Design

The case-control design is the most frequently employed approach in EWAS, comparing methylation patterns between individuals with a specific phenotype (cases) and those without (controls) [2]. This design is logistically feasible and cost-effective, allowing researchers to leverage existing DNA biobanks from previous studies [2]. The primary limitation is the inability to establish temporal relationships, making it difficult to determine whether methylation differences precede or result from the disease state [2].

Longitudinal Design

Longitudinal studies measure methylation at multiple timepoints within the same individuals, enabling the assessment of intra-individual changes over time [2]. This design is particularly valuable for understanding dynamic epigenetic processes throughout the lifespan, such as the extensive methylome remodeling that occurs during early childhood [2]. While logistically challenging and costly, longitudinal designs provide stronger evidence for causal inferences and can track methylation trajectories in relation to disease progression [2].

Specialized Design Considerations

Additional design considerations include family-based studies to estimate heritable components of methylation, twin studies to distinguish genetic and environmental influences, and integrated omics designs that combine EWAS with GWAS, transcriptomics, or proteomics data [2]. Each design requires specific analytical approaches to address potential confounding factors, particularly cell type composition in heterogeneous tissues like blood [2] [4].

Advanced Applications and Case Studies

EWAS of Clonal Hematopoiesis (CHIP)

A recent large-scale EWAS of clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP) illustrates the power of this approach in elucidating disease mechanisms [3]. This multiracial meta-analysis included 8,196 participants from four cohorts and identified distinct methylation signatures associated with different CHIP driver genes:

Figure 2: Integrated Workflow for CHIP EWAS Case Study

The study revealed that DNMT3A CHIP mutations were associated with widespread hypomethylation (5,987 of 5,990 CpGs), consistent with DNMT3A's role as a de novo methyltransferase [3]. In contrast, TET2 CHIP mutations showed predominantly hypermethylation (5,079 of 5,633 CpGs), aligning with TET2's function as a demethylase [3]. These findings were functionally validated using CRISPR-Cas9 engineered human hematopoietic stem cell models, demonstrating the mechanistic insights achievable through integrated EWAS approaches [3].

EWAS of Physical Activity

An EWAS of objectively measured physical activity demonstrated the application of this methodology to environmental exposures and lifestyle factors [5]. This study analyzed associations between sedentary behavior, moderate physical activity, and methylation patterns in pregnant women, identifying 122 CpG sites associated with moderate physical activity after adjusting for steps per day [5]. The study highlights challenges in EWAS of complex behaviors, including the need for precise exposure measurement and consideration of potential confounding factors [5].

Methodological Challenges and Solutions

EWAS faces several methodological challenges that require careful consideration in both study design and analysis:

Addressing Population Stratification

Similar to GWAS, population stratification can cause spurious associations in EWAS if not properly accounted for [4]. Traditional approaches use genetic principal components as covariates, but when genetic data are unavailable, methylation-based alternatives have been developed. Recent methodologies include methylation population scores (MPS), which use supervised learning to predict genetic ancestry from methylation data while adjusting for technical and environmental covariates [4]. These scores effectively capture population structure and can reduce test statistic inflation in EWAS of diverse populations [4].

Cell Type Heterogeneity

Cell type composition represents a major confounding factor in tissue-based EWAS, particularly in blood where methylation patterns vary substantially between leukocyte subsets [2] [4]. Reference-based estimation methods, such as Houseman's algorithm, use cell-type specific methylation signatures to deconvolute heterogeneous samples and estimate proportional composition [4] [5]. These estimates should be included as covariates in association analyses to avoid false positives arising from cellular heterogeneity rather than the phenotype of interest [2].

Reverse Causation and Causal Inference

A fundamental limitation of observational EWAS is the challenge of distinguishing cause from effect—whether methylation differences contribute to disease or result from disease processes [2]. Several approaches address this limitation:

- Longitudinal designs: Measure methylation before disease onset to establish temporal sequence [2]

- Mendelian randomization: Uses genetic variants as instrumental variables to infer causal relationships [3]

- Family-based designs: Control for shared genetic and environmental backgrounds [2]

- Integration with functional genomics: Combines EWAS with gene expression and mechanistic studies [3]

EWAS has matured into an essential component of functional genomics, providing unique insights into the molecular mechanisms through which genetic and environmental factors jointly influence complex traits and diseases. The continuing evolution of technologies—from microarrays to comprehensive sequencing approaches—promises enhanced coverage of regulatory elements and more precise mapping of methylation patterns [1]. Future directions include the integration of multi-omics data, development of single-cell epigenetic protocols, and application of machine learning approaches to identify complex epigenetic signatures of disease [1] [2].

The translation of EWAS findings into clinical applications continues to advance, with epigenetic biomarkers showing promise for disease risk prediction, diagnosis, and monitoring of therapeutic responses [1] [3]. As the field progresses, standardization of methodologies, improved reference datasets, and collaborative meta-analyses will further strengthen the robustness and reproducibility of EWAS discoveries across diverse populations and disease contexts [2] [4].

DNA Methylation as the Primary Epigenetic Marker in EWAS

DNA methylation (DNAm), characterized by the addition of a methyl group to a cytosine base in a CpG dinucleotide context, serves as a fundamental epigenetic mark that regulates gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence [6] [7]. This modification represents a crucial molecular interface that mediates the interaction between genetic predisposition and environmental exposures, providing critical insights into the pathophysiology of complex diseases [6] [2]. Epigenome-wide association studies (EWAS) systematically investigate genome-wide epigenetic variation to identify associations between DNA methylation patterns and phenotypes, environmental exposures, or disease states [8]. The viability of EWAS has been propelled by rapid advancements in high-throughput measurement technologies, particularly the Illumina Infinium DNA methylation BeadChip microarrays, which enable feasible methylation profiling at a near-genome-wide scale [6] [9].

The selection of DNA methylation as the primary epigenetic marker in EWAS is grounded in its stability, quantifiable nature, and well-characterized functional consequences. DNA methylation patterns are dynamic throughout the lifespan and exhibit tissue-specific signatures, yet remain sufficiently stable to yield reproducible associations in large-scale studies [7] [2]. As the most extensively studied epigenetic mechanism, DNA methylation provides a measurable molecular footprint of both genetic influences and environmental exposures, making it an ideal biomarker for investigating complex disease etiology [2].

Technological Platforms for Methylation Assessment

The evolution of microarray technologies has dramatically expanded the scope and precision of EWAS. The progression from the HumanMethylation27 (27K) to the HumanMethylation450 (450K) and subsequently to the MethylationEPIC (850K) arrays has substantially improved genomic coverage, particularly in regulatory regions beyond promoter-associated CpG islands [2]. The most recent innovation, the Methylation Screening Array (MSA), represents a strategic advance by concentrating coverage on trait-associated methylation signatures and cell-identity-associated methylation variations, achieving approximately 5.6 trait associations per site compared to approximately 2.2 in EPICv2 [9]. This targeted design enhances efficiency for large-scale population studies while maintaining critical biological information.

Table 1: Comparison of Illumina Methylation BeadChip Platforms

| Platform | CpG Coverage | Key Features | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| 27K | ~27,000 CpGs | Focus on promoter regions | Early EWAS, candidate gene validation |

| 450K | ~450,000 CpGs | Expanded coverage to gene bodies, intergenic regions | Mainstream EWAS, meQTL studies |

| EPIC/EPICv2 | ~850,000 CpGs | Enhanced coverage of enhancer regions (58% of FANTOM enhancers) | Comprehensive EWAS, regulatory element mapping |

| MSA | ~284,000 CpGs | Enriched for trait-associated loci (~5.6 traits/site); high-throughput 48-sample format | Population-scale screening, epigenetic clock applications |

For comprehensive methylation analysis, whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) remains the gold standard, providing base-resolution data across the entire methylome [7]. However, this method remains cost-prohibitive for large cohort studies. Reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) offers a cost-effective alternative by targeting CpG-rich regions, while emerging technologies like single-cell whole-genome methylation sequencing (scWGMS) are unlocking cellular heterogeneity but with limitations in sample throughput [9].

Experimental Workflow and Protocols

Standardized EWAS Workflow

A robust EWAS requires meticulous attention to experimental design, sample processing, and computational analysis. The following workflow diagram outlines the critical stages in a comprehensive EWAS investigation:

Sample Preparation and Bisulfite Conversion Protocol

Principle: Bisulfite conversion deaminates unmethylated cytosines to uracils, while methylated cytosines remain unchanged, allowing for discrimination based on methylation status [7] [2].

Procedure:

- DNA Quantification and Quality Assessment: Quantify DNA using fluorometric methods and assess purity (A260/280 ratio ~1.8-2.0). Ensure DNA integrity (DNA Integrity Number >7) for reliable results.

- Bisulfite Conversion: Use commercial bisulfite conversion kits with optimized protocols. Typical reaction conditions: 95°C for 30-60 seconds (denaturation), 50-60°C for 45-60 minutes (conversion), followed by clean-up.

- Conversion Efficiency Check: Include control DNA with known methylation patterns. Assess conversion efficiency through PCR amplification of non-CpG cytosines, which should be fully converted.

- Microarray Processing: Process bisulfite-converted DNA on selected Illumina BeadChip according to manufacturer's specifications, including amplification, fragmentation, hybridization, and scanning.

Technical Notes: Incomplete bisulfite conversion represents a major source of technical artifacts. Incorporate both unmethylated and fully methylated control DNA in each processing batch to monitor conversion efficiency [7].

Data Preprocessing and Quality Control Protocol

Software Implementation: Utilize established R packages such as minfi, ChAMP, or MethylCallR for standardized processing [10] [2].

Quality Control Steps:

- Signal Intensity Review: Remove samples with low intensity (detection p-value > 0.01 in >5% of probes).

- Probe Filtering: Exclude probes with:

- Detection p-value > 0.01 in >5% of samples

- Cross-reactive probes (mapping to multiple genomic locations)

- Probes overlapping SNPs at the CpG site or single-base extension

- Sex chromosome probes for autosomal-only analyses

- Normalization: Apply appropriate normalization methods (e.g., BMIQ, SWAN, Noob) to correct for technical variation between probe types and array positions.

- Batch Effect Correction: Implement ComBat or other empirical Bayesian methods to adjust for technical covariates (array, row, processing batch) [6].

- Outlier Detection: Use multidimensional scaling (MDS) and hierarchical clustering to identify sample outliers. Implement Mahalanobis distance methods to detect potential outlier samples within groups [10].

Cell Type Composition Estimation

Background: Tissue heterogeneity represents a major confounding factor in EWAS, particularly in blood-based studies where cellular composition varies substantially between individuals [2] [11].

Implementation:

- Reference-Based Deconvolution: Utilize established reference methylomes for purified cell types (e.g.,

Flowsorted.Blood.EPICfor blood samples) to estimate proportional composition [10]. - Reference-Free Methods: Apply methods such as MeDeCom, RefFreeCellMix, or EDec when appropriate reference datasets are unavailable [11].

- Statistical Adjustment: Include estimated cell type proportions as covariates in differential methylation analyses to account for heterogeneity effects.

Analytical Frameworks for Differential Methylation

Differential Methylation Position (DMP) Analysis

DMP analysis identifies individual CpG sites with statistically significant differences in methylation levels associated with the phenotype of interest. The easyEWAS package provides a battery of statistical methods tailored to different study designs [6]:

Table 2: Statistical Models for DMP Analysis in EWAS

| Model Type | Formula | Application Context | Output Metrics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Linear Model (GLM) | CpG = β₀ + β₁X₁ + β₂X₂ + ... + ε |

Case-control studies, continuous exposures | Regression coefficient (β), Standard Error, P-value | |

| Linear Mixed-Effects Model (LMM) | CpG = β₀ + β₁X₁ + ... + u + ε |

Longitudinal studies, repeated measures | β, SE, P-value with random effects (u) | |

| Cox Proportional Hazards (CoxPH) | `h(t | X) = h₀(t)exp(β₁CpG + ...)` | Time-to-event analysis, survival outcomes | Hazard Ratio (HR), 95% CI, P-value |

Implementation Protocol:

- Model Specification: Select appropriate statistical model based on study design. Adjust for relevant covariates including age, sex, batch effects, and estimated cell type proportions.

- Genome-Wide Analysis: Perform site-by-site analysis across all qualified CpG sites.

- Multiple Testing Correction: Apply Benjamini-Hochberg False Discovery Rate (FDR) or Bonferroni correction to account for multiple comparisons. A standard epigenome-wide significance threshold is P < 1×10⁻⁷ [3] [8].

- Effect Size Calculation: Report methylation differences as Δβ values (for β-values) or M-value coefficients, with typical biologically relevant effect sizes considered as |Δβ| ≥ 0.05 [10].

Differential Methylation Region (DMR) Analysis

DMR analysis identifies genomic regions containing multiple adjacent DMPs, often providing more biologically meaningful and robust findings than single CpG associations [6].

DMRcate Protocol:

- Initial Screening: Perform limma-based regression at each CpG site to generate moderated t-statistics and p-values.

- Gaussian Smoothing: Apply kernel smoothing to average effects across neighboring CpGs within a specified window (default: 1000 base pairs).

- Region Definition: Group adjacent CpG sites exceeding significance and effect size thresholds.

- Annotation: Annotate significant DMRs with genomic context (promoter, gene body, intergenic) and proximity to genes.

Bootstrap Internal Validation

To ensure robustness of EWAS findings, implement bootstrap resampling validation:

Procedure:

- Generate multiple resampled datasets (typically 1000+ iterations) through random sampling with replacement.

- Recalculate association statistics for each resampled dataset.

- Derive confidence intervals for regression coefficients using preferred method (percentile, studentized, or bias-corrected).

- Assess stability of significant DMPs across bootstrap iterations [6].

Advanced Analytical Concepts

Ternary-Code DNA Methylation Dynamics

Emerging research recognizes the importance of distinguishing between different cytosine modifications in the "ternary-code" - 5-methylcytosine (5mC), 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), and unmodified cytosine [9] [12]. This distinction is crucial as 5hmC represents an intermediate in active demethylation pathways and has distinct genomic distributions and functional consequences.

Profiling Protocol:

- bACE-seq: Apply bisulfite APOBEC-coupled epigenetic sequencing to discriminate 5mC from 5hmC.

- OxBS-seq: Utilize oxidative bisulfite sequencing for precise quantification of 5hmC.

- MSA with Modified Chemistry: Implement the methylation screening array with enhanced chemistry to capture 5hmC signatures [9].

The following diagram illustrates the ternary-code methylation concept and its functional implications:

Integration with Multi-Omics Data

Methylation Quantitative Trait Loci (meQTL) Analysis:

- Identify genetic variants associated with methylation variation.

- Assess cis-meQTLs (within 1Mb of CpG) and trans-meQTLs (distant associations).

- Integrate with GWAS findings to identify potential epigenetic mechanisms underlying genetic associations [2].

Expression Quantitative Trait Methylation (eQTM) Analysis:

- Correlate methylation levels with gene expression data from the same samples.

- Identify potentially regulatory relationships between methylation and transcription [3].

Mendelian Randomization:

- Utilize genetic instruments to infer causal relationships between methylation and disease outcomes.

- Apply two-sample MR approaches with summary statistics from large-scale EWAS and disease GWAS [3].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for EWAS

| Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function/Application | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microarray Platforms | Illumina EPICv2 BeadChip | Genome-wide methylation profiling (∼850,000 CpGs) | Balanced coverage of promoters, enhancers, gene bodies |

| Methylation Screening Array (MSA) | High-throughput trait association screening | 48-sample format; enriched for EWAS associations | |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits | EZ DNA Methylation kits (Zymo Research) | Convert unmethylated C to U while preserving 5mC | Critical for accurate methylation quantification |

| Computational Packages | Minfi | Preprocessing, normalization, QC of array data | Most cited for 450K data analysis |

| ChAMP | Comprehensive analysis pipeline | Increasingly cited for EPIC data analysis | |

| easyEWAS | User-friendly DMP and DMR analysis | Supports GLM, LMM, CoxPH models; bootstrap validation | |

| MethylCallR | EPICv2-compatible analysis framework | Handles duplicated probes; version conversion | |

| DMRcate | Differentially methylated region identification | Gaussian kernel smoothing approach | |

| Reference Datasets | FlowSorted.Blood.EPIC | Blood cell composition estimation | Reference-based deconvolution for blood samples |

| MeDeCom | Reference-free deconvolution | Identifies latent methylation components | |

| Functional Annotation | missMethyl | Gene set enrichment analysis | Accounts for probe number bias in array design |

Interpretation and Validation Guidelines

Functional Validation Strategies

Experimental Validation:

- Targeted Bisulfite Sequencing: Confirm top DMPs/DMRs using pyrosequencing or deep amplicon sequencing.

- In Vitro Models: Utilize CRISPR-Cas9 to introduce specific methylation changes in cell lines and assess functional consequences [3].

- Functional Assays: Perform luciferase reporter assays to assess regulatory potential of methylated regions.

Biological Interpretation:

- Genomic Context Analysis: Annotate significant CpGs with genomic features (promoters, enhancers, CpG islands, shores, shelves).

- Pathway Enrichment: Conduct gene set enrichment analysis using tools like

gomethto identify overrepresented biological pathways. - Integration with Public Resources: Compare findings with databases such as ENCODE, Roadmap Epigenomics, and GWAS catalog to prioritize functionally relevant hits.

Reporting Standards

Comprehensive EWAS reporting should include:

- Detailed sample characteristics and inclusion/exclusion criteria

- Complete description of preprocessing and normalization methods

- Cell type composition estimates and adjustment approach

- Multiple testing correction method and significance thresholds

- Effect sizes with confidence intervals for top associations

- Validation approaches and results

- Functional annotation of significant findings

DNA methylation profiling remains the cornerstone of epigenome-wide association studies, providing powerful insights into the molecular mechanisms linking genetic predisposition, environmental exposures, and disease phenotypes. The continued refinement of measurement technologies, analytical frameworks, and interpretation tools has established EWAS as an essential component of comprehensive biomedical research. By adhering to standardized protocols, implementing appropriate statistical methods, and applying rigorous validation strategies, researchers can leverage DNA methylation as a robust epigenetic marker to advance understanding of complex disease etiology and identify potential therapeutic targets.

Differentially Methylated Positions (DMPs) and Regions (DMRs)

Core Concepts and Biological Significance

Differentially Methylated Positions (DMPs) are individual cytosine-guanine dinucleotide (CpG) sites that exhibit statistically significant differences in methylation status between biological samples from distinct conditions (e.g., diseased versus normal, treated versus untreated) [13]. The methylation level at a single CpG site is typically quantified as a beta value (β), calculated as β = M/(M + U + α), where M represents the methylated allele intensity, U the unmethylated allele intensity, and α a constant offset (usually 100) to prevent division by zero [14]. DMP analysis provides high-resolution data but may miss broader, coordinated epigenetic patterns.

Differentially Methylated Regions (DMRs) are genomic segments, often spanning hundreds of base pairs, that contain multiple CpG sites showing consistent, statistically significant methylation differences between sample groups [15]. DMRs are regarded as possible functional regions involved in gene transcriptional regulation and provide a more biologically stable signature than single CpG sites, as they are less susceptible to technical noise [15] [13]. They are critical hallmarks of genomic imprinting, where they confer parent-of-origin-specific transcription, and are involved in normal human growth and neurodevelopment [16].

The following table summarizes the core characteristics and identification criteria for DMPs and DMRs.

Table 1: Defining Characteristics and Analysis Criteria for DMPs and DMRs

| Feature | Differentially Methylated Position (DMP) | Differentially Methylated Region (DMR) |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | A single CpG site with significant methylation difference between conditions [13]. | A genomic region with multiple CpGs showing consistent differential methylation [15]. |

| Typical Scope | Single nucleotide. | 50 bp to several kilobases. |

| Biological Significance | Point-specific epigenetic alteration; potential as a biomarker. | Stronger functional implication; often associated with regulatory elements like promoters and enhancers [15]. |

| Common Identification Criteria | Statistical test (e.g., t-test) with FDR correction; minimum methylation difference (e.g., Δβ ≥ 0.1) [17] [18]. | Multiple adjacent significant CpGs; minimum region length (e.g., 50 bp); statistical significance of the entire region [17] [13]. |

| Example Thresholds | FDR < 0.05, Δβ ≥ 0.1 [17]. | ≥ 3-5 CpGs, distance between CpGs ≤ 300 bp, MWU-test p-value < 0.05 [17] [13]. |

Analytical Workflows and Methodologies

The process of identifying DMPs and DMRs involves a multi-step workflow, from experimental profiling to computational analysis, with the specific approach varying based on the technology used.

Profiling Technologies and Data Acquisition

The choice of profiling technology dictates the scope and resolution of the methylation data.

Table 2: Key Technologies for Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Profiling

| Technology | Principle | Throughput | Resolution & Coverage | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infinium Methylation BeadChip (e.g., EPIC, MSA) [19] [9] | Hybridization of bisulfite-converted DNA to array probes. | High | Base-specific; ~850,000 to ~280,000 pre-selected CpG sites. | Large-scale EWAS, biomarker discovery. |

| Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) [19] | Sequencing following bisulfite conversion, which turns unmethylated cytosines to uracils. | Low | Base-specific; genome-wide. | Comprehensive discovery, novel DMR identification. |

| Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS) [19] | Restriction enzyme digestion followed by bisulfite sequencing. | Medium | Base-specific; covers ~85% of CpG islands, primarily in promoters. | Cost-effective targeted analysis. |

The workflow for analyzing data from these technologies, particularly from sequencing-based methods like WGBS and RRBS, follows a structured pipeline to ensure robust results, as illustrated below.

Detailed Protocol: DMP and DMR Analysis from WGBS/RRBS Data

This protocol provides a step-by-step guide for analyzing Bismark-generated coverage files in R to identify DMPs and DMRs [17].

1. Prerequisite: Set Up the R Environment

- Install and load the required Bioconductor packages.

2. Load and Organize Methylation Data

- Read Bismark coverage files and create a BSseq object for analysis.

3. Perform Differential Analysis

- DMP Detection using DSS: The DSS package uses a beta-binomial model to account for biological variation and over-dispersion in count data.

- DMR Detection using dmrseq: This package identifies DMRs by assessing the spatial autocorrelation of methylation differences across the genome.

Detailed Protocol: Analysis of Illumina Infinium BeadChip Data

The analysis of array-based methylation data requires specific steps to handle platform-specific biases, such as those arising from the two different probe types (Infinium I and II) [14].

1. Data Import and Quality Control (QC)

- Import raw IDAT files or preprocessed TXT files using the

minfipackage. - Perform rigorous QC:

- Filter probes with a high detection p-value (e.g., > 0.01).

- Remove probes on sex chromosomes (X, Y) to avoid gender bias.

- Exclude probes known to contain single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) or those that are cross-reactive [14].

2. Normalization and Type Bias Correction

- Apply within-array normalization for background correction and dye bias adjustment.

- Correct for the technical bias between Infinium I and II probes. The Beta Mixture Quantile normalization (BMIQ) method is a robust choice, as it calibrates the distribution of Infinium II probes to match that of the more stable Infinium I probes [14].

3. Differential Methylation Calling

- DMPs can be identified using linear models with the

limmapackage, which employs moderated t-statistics to enhance power in studies with small sample sizes [15] [14]. - DMRs can be called by aggregating nearby DMPs using packages like

BumphunterorDMRcate.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Resources for DMP/DMR Analysis

| Category | Item | Function and Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Commercial Kits | Gentra Puregene Kit (Qiagen) [18] | For DNA isolation from whole blood samples, ensuring high-quality input material. |

| PAXgene Blood RNA Kit (Qiagen) [18] | For RNA isolation, enabling integrated methylation and gene expression analysis. | |

| Illumina TotalPrep RNA Amplification Kit [18] | For synthesizing cRNA for gene expression beadchips. | |

| Bisulfite Conversion | Zymo Research EZ DNA Methylation Kits | Converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils while leaving methylated cytosines intact, a critical step for most profiling methods. |

| Microarray Platforms | Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip [18] [9] | Interrogates over 850,000 CpG sites; the EPIC version offers extensive coverage of regulatory regions. |

| Methylation Screening Array (MSA) [9] | The latest array design, highly enriched for trait-associated loci from EWAS, enabling ultra-high sample throughput. | |

| Critical Software & Databases | R/Bioconductor [17] [14] | The primary environment for statistical analysis and visualization (e.g., with packages like minfi, DSS, dmrseq). |

| Reference Genomes (UCSC, ENSEMBL) [19] | Essential for the alignment of sequencing reads and annotation of identified DMPs/DMRs. | |

| Public Repositories (GEO, TCGA) [19] | Sources for validation and comparison with public methylation datasets. |

Advanced Applications in Drug Development and Clinical Research

The identification of DMPs and DMRs has moved beyond basic research into applied clinical and pharmaceutical contexts.

Biomarker Discovery for Disease Diagnosis and Prognosis: Aberrant DNA methylation sites can function as powerful biomarkers for disease. For example, specific DMRs between cancer and normal samples demonstrate the aberrant methylation that is a hallmark feature of many cancers [19] [15]. These biomarkers can be used for early detection, molecular subtyping of diseases, and developing liquid biopsy-based diagnostics [19] [9].

Elucidating Mechanisms of CHIP and Cardiovascular Disease: Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP) is an age-related condition driven by mutations in genes like

DNMT3AandTET2, which are epigenetic regulators. A large EWAS revealed thatDNMT3AandTET2CHIP mutations have directionally opposing DNA methylation signatures, consistent with their canonical functions, and these changes are associated with increased cardiovascular disease risk [3]. This provides critical insight into the molecular mechanisms linking CHIP to age-related diseases.Understanding Environmental and Lifestyle Exposures: EWAS investigates how factors like alcohol consumption influence the epigenome. A 2025 study identified 19,255 CpG sites associated with alcohol consumption, with over-representation of genes involved in cancer, the nervous system, and aging [20]. This helps in understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying the harmful effects of environmental exposures.

The process from foundational analysis to clinical application involves integrating multiple data types to build a compelling case for a biomarker or drug target, as shown in the following workflow.

The Dynamic Interplay Between Genetics, Environment, and the Epigenome

Epigenome-wide association studies (EWAS) represent a powerful methodological framework for investigating the interface at which genetic predisposition and environmental exposures interact to influence complex disease risk and outcomes [2] [21]. Unlike genetic variants, which remain static throughout life, epigenetic modifications are dynamic and reversible, reflecting both inherited factors and lifetime environmental experiences [22]. The primary aim of an EWAS is to examine genome-wide epigenetic variants, predominantly DNA methylation at cytosine-phosphate-guanine (CpG) dinucleotides, to detect statistically significant differences associated with phenotypes of interest [2]. These studies have emerged as a complementary approach to genome-wide association studies (GWAS), providing insights into the molecular mechanisms through which both genetic and environmental factors converge to influence health and disease [21].

The most extensively studied epigenetic marker in EWAS is DNA methylation, which involves the covalent addition of a methyl group to the 5-carbon position of cytosine residues, primarily within CpG dinucleotides [22]. This modification can regulate gene expression by altering transcription factor binding or recruiting methyl-binding proteins that remodel chromatin structure [22]. Modern EWAS primarily utilizes array-based technologies such as the Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip (450K) and the more recent MethylationEPIC BeadChip (EPIC), which Interrogate approximately 450,000 and 850,000 CpG sites respectively [2] [22]. The measurement output is typically represented as beta-values ranging from 0 (completely unmethylated) to 1 (fully methylated), quantifying the methylation fraction at each CpG site [5] [22].

Current Research Landscape in EWAS

Key Application Areas

EWAS approaches have been successfully applied to diverse research areas, illuminating how various exposures and biological processes epigenetically regulate gene expression. The table below summarizes prominent EWAS application areas, their specific focuses, and key findings from recent studies.

Table 1: Key Application Areas of Epigenome-Wide Association Studies

| Application Area | Specific Focus | Key Findings | Representative Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clonal Hematopoiesis | CHIP (Clonal Hematopoiesis of Indeterminate Potential) | Identification of 9615 CpGs associated with any CHIP; DNMT3A and TET2 mutations show opposing methylation patterns [3] | Multiracial meta-analysis (N=8196) [3] |

| Bone Diseases | Osteoporosis and osteoarthritis | Identification of differentially methylated regions in osteoporosis and osteoarthritis [23] | Delgado-Calle et al. (2013) [23] |

| Nutritional Exposure | Dietary patterns, specific foods, micronutrients | Consistent associations at 9 CpG sites (AHRR, CPT1A, FADS2) with fatty acid consumption [22] | Scoping review of 30 studies [22] |

| Physical Activity | Objectively measured sedentary behavior and moderate activity | Association of 122 CpG sites with moderate physical activity after adjustment for steps/day [5] | EPIPREG cohort (n=353) [5] |

| Substance Exposure | Smoking and vaping | Identification of differentially methylated regions using Bonferroni-significance threshold of p < 5.91 × 10–8 [24] | EWAS protocol for vaping vs. non-smokers [24] |

Analytical Approaches in EWAS

The analytical workflow in EWAS encompasses multiple stages, from quality control to advanced statistical analyses. Two main bioinformatics packages—Minfi and ChAMP—have emerged as open-source tools for processing and analyzing methylation array data [2]. These packages allow researchers to import raw data files, perform quality control, normalization, and detect both differentially methylated positions (DMPs) and regions (DMRs) [2]. Downstream analyses may include methylation quantitative trait loci (methQTL) analysis to identify genetic variants influencing methylation patterns, expression quantitative trait methylation (eQTM) analysis to link methylation changes with gene expression, and causal inference methods like Mendelian randomization to infer potential causal relationships between methylation and disease [3] [2].

Table 2: Common Analytical Approaches in EWAS

| Analytical Method | Purpose | Key Features | Tools/Packages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quality Control | Identify poor-quality samples and probes | Filtering based on detection p-values, bead count, removal of cross-reactive and SNP-containing probes [5] | Meffil [5], Minfi [2] |

| Normalization | Remove technical variation while preserving biological signals | Functional normalization using control probes or reference datasets [5] | Meffil [5], ChAMP [2] |

| DMP Identification | Find individual CpGs associated with traits | Linear regression with multiple testing correction (Bonferroni, FDR) [2] [24] | Minfi, ChAMP, standard statistical software |

| DMR Identification | Identify genomic regions with coordinated methylation changes | Regions containing ≥2 CpGs within 500bp with consistent effects [24] | dmrff R package [24] |

| Cell Type Deconvolution | Estimate cell-type proportions in mixed samples | Reference-based estimation using cell-type specific methylation markers [2] | Houseman's method [5] |

| Causal Inference | Infer potential causal relationships | Mendelian randomization using genetic instruments [3] [2] | Two-sample MR methods |

Experimental Protocols for EWAS

Multi-Cohort EWAS on Clonal Hematopoiesis

Study Design and Participant Recruitment

This protocol outlines the methods for a recent large-scale EWAS investigating the epigenetic signatures of clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP) [3]. The study employed a multiracial meta-analysis design, pooling data from four independent cohort studies: the Framingham Heart Study (FHS), Jackson Heart Study (JHS), Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS), and Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study, with a total sample size of N = 8,196 participants (462 with any CHIP, 261 with DNMT3A CHIP, 84 with TET2 CHIP, and 21 with ASXL1 CHIP) [3]. Participant characteristics included mean ages ranging from 56-74 years, with a higher proportion of women (54-63%) across all cohorts. CHIP mutations with a variant allele frequency (VAF) ≥ 2% were present in 4-15% of participants across cohorts, with the three most frequently mutated CHIP driver genes being DNMT3A, TET2, and ASXL1 [3].

Laboratory Methods

DNA Methylation Processing: DNA methylation was quantified using the Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip (Illumina, San Diego, California, USA), which measures the proportion of methylation at approximately 850,000 CpG sites, generating beta-values ranging from 0 to 1 [5]. Quality control procedures included:

- Removal of sample outliers based on methylated/unmethylated ratio (> 3SD)

- Exclusion of outliers in bisulfite control probes (> 5 SD)

- Filtering of probes with detection p-value < 0.01 and bead count < 3

- Omission of probes on sex chromosomes, cross-reactive probes, and probes containing single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) [5]

Functional Validation: EWAS findings were validated using human hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) models of CHIP. Loss-of-function mutations in DNMT3A, TET2, and ASXL1 were introduced into mobilized peripheral blood CD34+ hematopoietic cells using CRISPR-Cas9 [3]. After seven days in culture, CD34+CD38-Lin- cells were isolated using fluorescence-activated cell sorting, genomic DNA was extracted, and methylation was assayed using biomodal duet evoC [3].

Statistical Analysis

The analysis employed race-stratified epigenome-wide association analyses followed by multiracial meta-analysis [3]. Key analytical steps included:

- Association Testing: Multivariable linear regression at each CpG site, adjusting for age, sex, genetic ancestry, and estimated blood cell composition [3]

- Multiple Testing Correction: Bonferroni-corrected significance threshold of P < 1×10^-7 [3]

- Meta-Analysis: Fixed-effects meta-analysis of race-stratified results using inverse variance weighting

- Sensitivity Analyses: Exclusion of CHIP cases with VAF < 10% to assess robustness of findings

- eQTM Analysis: Expression quantitative trait methylation analysis to identify transcriptomic changes associated with CHIP-associated CpGs

- Causal Inference: Two-sample Mendelian randomization to investigate potential causal relationships between CHIP-associated CpGs and cardiovascular traits [3]

EWAS of Objectively Measured Physical Activity

Study Design and Physical Activity Measurement

This protocol describes methods for an EWAS investigating associations between objectively measured physical activity and DNA methylation in peripheral blood leukocytes [5]. The discovery analysis was conducted in pregnant women from the Epigenetics in Pregnancy (EPIPREG) cohort, including 244 European and 109 South Asian women with both DNA methylation and objectively measured physical activity data [5].

Physical Activity Assessment: Physical activity was measured using the SenseWear Pro3 armband (BodyMedia Inc, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) at approximately gestational week 28. Participants wore the device continuously for 4-7 days, excluding water activities. Data were analyzed using manufacturer software (SenseWear Professional Research Software Version 6.1), with valid day defined as ≥ 19.2 hours of wear time [5]. The analysis extracted:

- Number of steps per day

- Mean hours/day of moderate-intensity physical activity (MPA) (3.0-6.0 METs)

- Sedentary behavior (SB) (< 1.5 METs) [5]

Laboratory Methods

DNA Methylation Quantification: DNA methylation was assessed in peripheral blood leukocytes using the Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip (Illumina) [5]. Quality control procedures implemented in the Meffil R package included:

- Removal of 6 sample outliers based on methylated/unmethylated ratio (> 3SD)

- Exclusion of 1 outlier in bisulfite control probes (> 5 SD)

- Removal of 1 sample with sex mismatch

- Filtering of probes with detection p-value < 0.01 and bead count < 3

- Functional normalization standardized for 10 principal components and batch effects [5]

Genotyping: Performed using the CoreExome chip (Illumina), interrogating approximately 250,000 single nucleotides across the genome. Quality control included filtering genetic variants that deviated from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (p = 1.0 × 10^-4), with low call rate (< 95%), and with minor allele frequency (MAF) < 1% [5].

Statistical Analysis

EWAS Models: Two primary models were employed:

- Model 1: Linear mixed model adjusted for age, smoking, blood cell composition, with ancestry as random intercept

- Model 2: Model 1 with additional adjustment for total number of steps per day [5]

Multiple Testing Correction: False discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 was applied to identify significant associations [5].

Downstream Analyses:

- Association of significant CpG sites with cardiometabolic phenotypes

- Methylation quantitative trait loci (methQTL) analysis to identify genetic variants influencing methylation

- Expression quantitative trait methylation (eQTM) analysis to link methylation with gene expression [5]

Visualization of EWAS Workflows and Biological Relationships

Integrated EWAS Workflow from Sample to Discovery

Genetic and Environmental Influences on the Epigenome

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for EWAS

| Category | Item/Reagent | Specification | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methylation Arrays | Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip | ~850,000 CpG sites | Genome-wide methylation profiling [2] [5] |

| Methylation Arrays | Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip | ~450,000 CpG sites | Genome-wide methylation profiling [2] [22] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | ChAMP (Chip Analysis Methylation Pipeline) | R/Bioconductor package | Quality control, normalization, DMP/DMR detection [2] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Minfi | R/Bioconductor package | Quality control, normalization, DMP/DMR detection [2] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Meffil | R package | Quality control, normalization, cell composition estimation [5] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | dmrff | R package | Differentially methylated region identification [24] |

| Functional Validation | CRISPR-Cas9 | Gene editing system | Introduction of specific mutations in cell models [3] |

| Functional Validation | CD34+ hematopoietic cells | Primary human cells | Model system for hematopoietic studies [3] |

| Functional Validation | Biomodal duet evoC | Methylation assay platform | Targeted methylation validation [3] |

| Cell Composition | Houseman's Reference-based Algorithm | Computational method | Blood cell type proportion estimation [5] |

EWAS provides a powerful framework for elucidating the dynamic interplay between genetic susceptibility and environmental exposures in shaping disease risk. The protocols and methodologies outlined in this application note highlight the rigorous approaches required for conducting robust epigenome-wide association studies, from careful study design and appropriate sample selection through sophisticated bioinformatic analyses and functional validation. As the field continues to evolve, emerging technologies including long-read sequencing for more comprehensive methylation profiling and multi-omics integration approaches will further enhance our ability to decipher the complex relationships between the genome, environment, and epigenome in human health and disease.

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and epigenome-wide association studies (EWAS) represent two powerful hypothesis-free approaches for identifying molecular associations with complex traits and diseases. While both methodologies conduct genome-wide searches for associations, they interrogate fundamentally distinct molecular layers and biological mechanisms. GWAS identifies associations between trait variation and genetic variation, primarily single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), which are largely static throughout an individual's lifetime [25]. In contrast, EWAS assesses associations between traits and DNA methylation (DNAm) at cytosine-guanine dinucleotides (CpG sites), an epigenetic modification that can dynamically respond to environmental exposures, developmental stages, and disease processes [3] [26].

The biological distinction between these approaches has profound implications for the interpretation of results. GWAS associations typically reflect the influence of inherited or acquired genetic variants on disease risk, either directly or through linkage disequilibrium with causal variants [25]. EWAS associations, however, can arise through multiple causal pathways: forward causation (where DNAm influences the trait), reverse causation (where the trait influences DNAm), or confounding (where a separate factor influences both DNAm and the trait) [25]. Recent evidence suggests that DNAm associations with complex traits are frequently attributable to confounding or reverse causation rather than DNAm itself being causal [25].

Key Mechanistic Distinctions Between EWAS and GWAS

Fundamental Biological Principles

The core distinction between GWAS and EWAS lies in their respective biological substrates. GWAS investigates variations in the DNA sequence itself, which remains essentially unchanged throughout an individual's lifetime (except for somatic mutations). EWAS investigates epigenetic modifications, specifically DNA methylation, which represents a dynamic layer of molecular regulation that can change in response to various internal and external factors without altering the underlying DNA sequence [27] [26].

This fundamental difference translates to divergent temporal dynamics in what each method captures. Genetic variants identified by GWAS are fixed (with exceptions for somatic mutations) and present from conception, potentially predisposing individuals to diseases decades before onset. DNA methylation patterns measured in EWAS can reflect current environmental exposures, disease processes, or the cumulative effects of past experiences, making them potentially valuable as biomarkers of disease progression or recent environmental interactions [28] [26].

Causal Inference and Interpretative Challenges

The interpretation of GWAS and EWAS results requires careful consideration of fundamentally different causal frameworks:

GWAS Interpretation: A genetic variant associated with a trait may be causal itself or in linkage disequilibrium with a causal variant. While confounding factors like population stratification exist, statistical adjustments routinely address these issues, and the identified associations with genetic variants are unlikely to be consequences of the disease itself [25] [29].

EWAS Interpretation: DNAm associations can arise from multiple pathways, creating significant interpretative challenges. As illustrated in the causal diagram below, EWAS signals can represent: (1) Forward Causation: DNAm differences causally influencing disease risk; (2) Reverse Causation: Disease processes altering DNAm patterns; or (3) Confounding: Unmeasured environmental or genetic factors influencing both DNAm and disease risk independently [25].

Causal Pathways in EWAS: DNA methylation can be influenced by genetics and environment, and can both influence and be influenced by disease, creating complex causal relationships.

Mendelian randomization analyses have provided evidence that for many complex traits, such as BMI, EWAS signals predominantly reflect reverse causation (the trait causing changes in DNAm) rather than DNAm causing the trait [25]. This contrasts sharply with GWAS, where the direction of effect is typically from genetic variant to trait.

Study Design and Technical Considerations

GWAS and EWAS differ significantly in their technical implementation and analytical challenges:

Cell Type Specificity: DNA methylation patterns are highly cell-type-specific, making EWAS results particularly sensitive to cellular heterogeneity. Failure to properly account for differences in cell type composition between cases and controls can create spurious associations [3] [4]. GWAS is generally less affected by this issue.

Population Stratification: Both methods are susceptible to confounding by population structure, but the approaches for correction differ. GWAS typically uses genetic principal components (GPCs) derived from genome-wide SNP data [4]. EWAS can leverage methylation population scores (MPSs) that predict genetic ancestry using carefully selected CpG sites, which is particularly valuable when genetic data are unavailable [4].

Temporal Dynamics: GWAS requires only a single DNA sample per individual as genotypes are stable. EWAS may benefit from longitudinal sampling to capture dynamic epigenetic changes, giving rise to the concept of Longitudinal Epigenome-Wide Association Studies (LEWAS) that track how somatic epitypes change over time in response to environmental exposures [26].

Table 1: Fundamental Distinctions Between GWAS and EWAS Approaches

| Feature | GWAS | EWAS |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Target | Genetic variants (SNPs) | DNA methylation (CpG sites) |

| Temporal Stability | Largely static throughout life | Dynamic, responsive to environment |

| Primary Biological Sample | DNA from any tissue (germline) | Tissue-specific DNA recommended |

| Key Confounders | Population stratification, kinship | Cell type heterogeneity, environmental exposures |

| Causal Interpretation | Generally unidirectional (variant to trait) | Multidirectional (forward, reverse, confounding) |

| Typical Sample Sizes | Often very large (N > 50,000) | Smaller (N > 4,500) but increasing [25] |

Complementary Biological Insights from GWAS and EWAS

Empirical Evidence of Overlap and Divergence

Systematic comparisons of GWAS and EWAS results for 15 complex traits reveal that these approaches typically capture distinct biological aspects. One comprehensive analysis found that for most traits, GWAS and EWAS identified substantially different genomic regions, with the number of regions identified by one method but not the other far exceeding the number of overlapping regions [25].

Notable exceptions exist, such as diastolic blood pressure, which showed significant overlap in both identified genes (P = 5.2 × 10⁻⁶) and gene ontology terms (P = 0.001) between GWAS and EWAS [25]. However, for most traits, the magnitude of GWAS effect estimates in a genomic region had limited ability to predict whether DNAm sites in the same region would be associated with the trait (AUC range = 0.43–0.61) [25].

Simulation studies suggest that the degree of overlap between GWAS and EWAS findings depends on the underlying genetic and epigenetic architecture. The overlap increases with both study sample sizes and the proportion of DMPs that are causal for the trait rather than consequences of the trait or confounding [25].

Biological Context: CHIP as a Case Study

Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP) provides an illustrative example of how GWAS and EWAS offer complementary insights. CHIP involves age-related expansion of blood stem cells with leukemogenic mutations and increases risk for cardiovascular disease and other age-related conditions [3].

EWAS of CHIP has revealed thousands of CpG sites associated with CHIP status, with characteristic signatures for different driver genes. DNMT3A and ASXL1 CHIP mutations are predominantly associated with DNA hypomethylation, while TET2 CHIP shows primarily hypermethylation, consistent with the known functions of these genes as epigenetic regulators [3]. These EWAS findings were functionally validated using human hematopoietic stem cell models of CHIP [3].

Notably, the vast majority of CHIP-associated CpGs (>99%) were located remotely (>1 Mb) from the driver genes themselves [3], demonstrating how EWAS can identify downstream epigenetic consequences of genetic mutations that would not be detected through GWAS alone.

Table 2: Comparison of GWAS and EWAS Findings for Selected Complex Traits

| Trait | GWAS Insights | EWAS Insights | Degree of Overlap |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diastolic Blood Pressure | 97 independent loci identified in N ~330,000 [25] | 187 independent loci identified in N ~10,000 [25] | Substantial (Gene overlap P = 5.2×10⁻⁶) [25] |

| CHIP | Identifies genetic variants in driver genes (DNMT3A, TET2, ASXL1) [3] | Reveals downstream epigenetic consequences & remote regulatory effects [3] | Minimal (EWAS captures downstream effects) |

| Severe Obesity | 3 novel signals in known BMI loci (TENM2, PLCL2, ZNF184) [30] | Limited current data | Not assessed |

| Biological Aging | Limited identification of genetic variants associated with aging pace [28] | Multiple epigenetic clocks (Horvath, GrimAge, DunedinPACE) track chronological and biological aging [28] | Not directly comparable |

Integrated Protocols for GWAS and EWAS

Standard EWAS Protocol

The following workflow outlines a comprehensive protocol for conducting an epigenome-wide association study:

EWAS Workflow: Steps from sample collection to functional validation in an epigenome-wide association study.

Step 1: Sample Collection and Processing

- Collect appropriate tissue samples (considering tissue specificity of DNA methylation)

- Extract high-quality genomic DNA

- Treat DNA with bisulfite using kits such as EZ-96 DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research) to convert unmethylated cytosines to uracils while leaving methylated cytosines unchanged [4]

Step 2: Methylation Profiling

- Perform genome-wide methylation analysis using Illumina Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip or similar platforms covering >850,000 CpG sites

- Process arrays using Illumina GenomeStudio or equivalent software with genotyping call rate threshold ≥0.98 [4]

Step 3: Quality Control and Normalization

- Apply normal-exponential deconvolution using out-of-band probes (Noob) background subtraction for normalization [4]

- Implement BMIQ method for probe-type bias correction [4]

- Perform ComBat or similar batch correction methods to address technical variability [4]

Step 4: Cell Type Composition Estimation

- Estimate cell type subpopulations using reference-based Houseman's method [4]

- Include estimated cell type proportions as covariates in association analyses

Step 5: Association Analysis

- Test associations between methylation β-values (ranging from 0 to 1, representing proportion methylated) and traits of interest using linear or logistic regression

- Adjust for key covariates: age, sex, smoking status, body mass index, technical factors, and cell type proportions [3] [4]

- Address population stratification using methylation population scores (MPSs) when genetic data are unavailable [4]

Step 6: Functional Follow-up

- Annotate significant CpG sites to nearby genes and regulatory regions

- Conduct expression quantitative trait methylation (eQTM) analysis to link methylation changes with gene expression [3]

- Perform pathway enrichment analysis to identify biological processes affected

Causal Inference Protocol for EWAS Findings

Establishing causal relationships in EWAS requires specialized methodological approaches:

Mendelian Randomization Analysis

- Identify genetic instruments (methylation quantitative trait loci, meQTLs) for significant CpG sites

- Apply two-sample Mendelian randomization to test causal relationships between DNAm and traits [3]

- Sensitivity analyses (e.g., MR-Egger, weighted median) to assess pleiotropy and strengthen causal inference

Longitudinal EWAS (LEWAS) Design

- Collect serial samples from participants over time [26]

- Measure DNA methylation at multiple timepoints along with detailed environmental exposure histories

- Model temporal relationships between exposure, methylation changes, and disease onset

Experimental Validation

- Utilize in vitro models (e.g., CRISPR-Cas9 in human hematopoietic stem cells) to functionally validate EWAS findings [3]

- Assess the functional impact of methylation changes on gene expression and cellular phenotypes

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for EWAS and Integrated Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Methylation Kits | Bisulfite conversion of DNA for methylation analysis | EZ-96 DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research) [4] |

| Methylation Arrays | Genome-wide methylation profiling | Illumina Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip (~850,000 CpGs) [4] |

| Cell Sorting Technology | Isolation of specific cell populations for cell-type-specific analysis | Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) for CD34+CD38-Lin- cells [3] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Genetic engineering for functional validation | CRISPR-Cas9 for introducing loss-of-function mutations in candidate genes [3] |

| Methylation Analysis Software | Quality control, normalization, and statistical analysis | R packages: Minfi (normalization), SeSAMe (processing) [4] |

| Reference Methylation Databases | Cell type deconvolution and comparison | Reference methylation signatures for estimating cell type proportions [4] |

Integrated Analysis and Interpretation Framework

The most powerful insights into complex traits emerge from integrating GWAS and EWAS findings within a unified analytical framework. This integration acknowledges that genetic and epigenetic factors work in concert to influence disease risk and progression.

Genetic-Epigenetic Integration Approaches:

- Overlap Analysis: Systematically test whether genes and gene sets identified by GWAS and EWAS show significant overlap, as performed for 15 complex traits [25]

- Mediation Analysis: Assess whether DNA methylation mediates the effects of genetic variants on complex traits

- Multi-omic Pathway Integration: Combine GWAS-identified genetic risk factors with EWAS-identified epigenetic changes to map comprehensive molecular pathways

Interpretative Guidelines:

- Significant overlap between GWAS and EWAS findings may indicate that DNA methylation changes are either tagging molecular features relevant to trait etiology or are on the causal pathway from genetic variant to disease [25]

- Divergent findings suggest that EWAS may capture environmental influences, disease consequences, or age-related changes not reflected in genetic risk factors

- The strong environmental sensitivity of DNA methylation means EWAS can provide insights into modifiable risk factors, even when findings reflect reverse causation or confounding

GWAS and EWAS offer distinct yet complementary windows into the biology of complex traits. While GWAS identifies largely static genetic risk factors, EWAS captures dynamic epigenetic modifications that reflect both genetic influences and environmental exposures. The mechanistic distinctions between these approaches mean they often highlight different genes and biological pathways, together providing a more comprehensive understanding of disease etiology than either method alone.

Future research should prioritize integrated analyses that leverage the complementary strengths of both approaches, along with longitudinal designs and causal inference methods to disentangle the complex relationships between genetics, epigenetics, environment, and disease. The development of increasingly sophisticated functional validation protocols will be essential for translating GWAS and EWAS findings into mechanistic insights and therapeutic opportunities.

EWAS in Practice: Methodological Workflows and Translational Applications

Within the framework of epigenome-wide association studies (EWAS) design and analysis, the selection of an appropriate study design is a critical determinant of scientific validity and translational impact. EWAS investigates genome-wide epigenetic variants, most commonly DNA methylation, to identify associations with phenotypes of interest [2] [8]. The epigenome serves as a biological interface where genetic predispositions and environmental exposures interact, driving the etiology and pathophysiology of complex diseases [2]. This application note provides a structured comparison of case-control, longitudinal, and family-based designs specifically tailored for EWAS investigations, equipping researchers with practical protocols for implementation in drug development and basic research.

The table below summarizes the fundamental characteristics, applications, and methodological considerations of the three primary study designs in EWAS research.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of EWAS Study Designs

| Design Aspect | Case-Control | Longitudinal | Family-Based |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temporal Framework | Retrospective, cross-sectional | Prospective, repeated measures | Cross-sectional or prospective with kinship |

| Primary Application | Hypothesis generation; association screening | Tracking intra-individual change; establishing temporal sequence | Controlling for genetic/environmental confounding |

| Key Strength | Logistically feasible; efficient for rare outcomes | Captures dynamic methylation processes; reduces reverse causation | Controls for population stratification; assesses transgenerational inheritance |

| Major Limitation | Susceptible to reverse causation; confounding | Time-consuming; expensive; participant attrition | Limited availability of large family cohorts |

| Optimal Phenotypes | Prevalent diseases with stable epigenetic signatures | Developmental trajectories; progressive disorders | Heritable conditions with potential epigenetic transmission |

| Sample Size Efficiency | High | Moderate to low | Low to moderate |

| Cost Efficiency | High | Low | Moderate |

Case-Control Study Design

Conceptual Framework and Applications

Case-control studies represent the most frequently employed design in EWAS [2]. This design compares unrelated participants with a specific phenotype (cases) to those without the phenotype (controls) in a cross-sectional manner [2] [8]. Cases and controls are typically matched for potential confounding factors such as age, sex, ethnicity, or genotype at loci previously associated with the phenotype [2]. The primary advantage of this approach is logistical feasibility, particularly when utilizing existing DNA biobanks from previous genome-wide association studies [2].

A significant methodological limitation is the inability to determine temporal relationships—specifically, whether differential methylation precedes disease onset (potentially causal) or results from the disease process (reverse causation) [2] [31]. Case-control EWAS are therefore typically restricted to claims of association rather than causation, though auxiliary approaches like Mendelian randomization can sometimes help infer causal relationships [2].

Implementation Protocol

Step 1: Case Definition and Ascertainment

- Define cases using specific, multi-component diagnostic criteria [32]

- Establish explicit inclusion/exclusion criteria addressing disease heterogeneity

- Source cases from clinical populations, disease registries, or existing cohorts

Step 2: Control Selection

- Select controls from the same 'study base' as cases to minimize selection bias [32]

- Consider control sources: general population, relatives/friends, or hospital patients [32]

- Implement matching for key confounders (age, sex, technical variables)

- Avoid control groups with diseases known to share epigenetic risk factors with the case condition [32]

Step 3: Sample Size Calculation

- Conduct power analysis based on expected methylation differences

- Account for multiple testing (typically P < 1×10⁻⁷ for epigenome-wide significance) [8]

- Consider expected effect sizes (typically small in EWAS: 2-10% methylation differences)

Step 4: Laboratory Processing

- Utilize Illumina MethylationEPIC array or similar platform [2]

- Process samples in randomized batches to avoid technical confounding

- Include replicate samples for quality control

Step 5: Data Analysis

- Conduct site-by-site analysis using linear or logistic regression [8]

- Adjust for cell-type composition using reference-based or reference-free methods [31]

- Correct for multiple testing using false discovery rate or Bonferroni methods

- Validate significant hits in independent cohorts when possible

Longitudinal Study Design

Conceptual Framework and Applications

Longitudinal EWAS tracks the same individuals over time, measuring methylation and phenotype at multiple timepoints [2] [8]. This design is particularly valuable for capturing the dynamic nature of DNA methylation across the lifespan, especially during early years when the methylome undergoes significant remodeling [2]. The major advantage is the ability to establish temporal relationships between methylation changes and phenotypic outcomes, potentially distinguishing causal epigenetic events from consequences of disease processes [2].

Natural history studies that track methylation trajectories from birth in healthy individuals represent the most common form of longitudinal EWAS [2]. However, establishing longitudinal studies for disease states is challenging due to the difficulty in obtaining pre-disease onset samples [2]. The significant time and financial investments required for longitudinal designs remain prohibitive for many research groups [2].

Implementation Protocol

Step 1: Study Type Selection

- Choose between accelerated longitudinal design (multiple cohorts at different starting ages) or single cohort design [33]

- Determine measurement frequency based on expected rate of epigenetic change

- Establish follow-up duration sufficient to capture relevant transitions

Step 2: Participant Recruitment and Retention

- Implement strategies to minimize attrition (regular contact, incentives)

- Obtain consent for long-term participation and potential re-contact

- Plan for ethical challenges in vulnerable populations (e.g., cancer patients) [34]

Step 3: Data Collection Timepoints

- Schedule assessments to capture critical developmental or disease transitions

- Collect comprehensive environmental exposure data at each timepoint

- Standardize biospecimen collection, processing, and storage protocols

Step 4: Laboratory Considerations

- Maintain consistent laboratory methods across timepoints

- Include technical replicates and reference materials to account for batch effects

- Consider using the same laboratory personnel for all measurements when possible

Step 5: Statistical Analysis

- Employ linear mixed effects models to account for within-subject correlations [33]

- Model change over time with age as the time metric [33]

- Test for both cross-sectional and longitudinal effects [33]

- Account for potential cohort effects in accelerated longitudinal designs [33]

Family-Based Study Design

Conceptual Framework and Applications

Family-based designs in EWAS utilize kinship structures to control for genetic and environmental confounding [8]. These designs are particularly valuable for studying transgenerational inheritance patterns of epigenetic marks and distinguishing between genetic and epigenetic effects [8]. By comparing related individuals, these designs can control for population stratification—a significant concern in epigenetic studies where methylation patterns can be influenced by genetic variation [31].

Monozygotic twin studies represent a powerful variant of family-based designs, as twins share identical genomic information [8]. When monozygotic twins are discordant for a particular disease or phenotype, observed epigenetic differences are likely associated with the phenotype rather than genetic variation [8]. A limitation of this approach is the challenge of recruiting sufficiently large cohorts of discordant monozygotic twins with the disease of interest [8].

Implementation Protocol

Step 1: Pedigree Selection and Ascertainment

- Define inclusion criteria based on family structure (sibling pairs, parent-offspring trios, extended pedigrees)