Epigenetic Regulatory Networks: Master Controllers of Cellular State in Health and Disease

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the Epigenetic Regulatory Network (ERN), a complex system of interdependent modifications that dictates cellular identity and function.

Epigenetic Regulatory Networks: Master Controllers of Cellular State in Health and Disease

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the Epigenetic Regulatory Network (ERN), a complex system of interdependent modifications that dictates cellular identity and function. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, we dissect the foundational principles of the ERN, detailing its key components: DNA methylation, histone modifications, chromatin remodeling, and non-coding RNAs. The scope extends to cutting-edge investigative methodologies, including epigenetic editing and multi-omics integration, and addresses the significant challenges of redundancy and therapeutic resistance. Finally, we evaluate the translational potential of targeting the ERN, reviewing advances in epigenetic therapies and their application in oncology and other diseases, thereby offering a roadmap for leveraging epigenetic networks in precision medicine.

Deconstructing the Epigenetic Regulatory Network: Core Mechanisms and Homeostatic Control

The Epigenetic Regulatory Network (ERN) represents the interconnected system of proteins and pathways that govern the establishment, maintenance, and modulation of chromatin and DNA methylation landscapes, controlling the functional output of the genome and defining cellular states and behaviors [1]. Unlike traditional studies that focus on individual epigenetic modifiers, the network perspective reveals how hundreds of proteins of diverse function cooperate in defining chromatin structure and DNA methylation landscapes, with emergent system-level properties such as robustness and bistability ensuring consistent genome function across environmental and cell-intrinsic fluctuations [1]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to defining the ERN, with specific methodologies and resources for researchers investigating how epigenetic networks control cellular states in health and disease.

Reversible covalent modifications of DNA and histones, histone variants, chromatin remodeling, and higher-order compaction form multiple regulatory layers that integrate to control gene expression profiles and maintain genome integrity [1]. The identification of writers, readers, and erasers of epigenetic modifications, along with biochemical characterization of multi-protein complexes, has enabled deep characterization of many pathways, yet how different classes of epigenetic regulators interact to build a resilient ERN remains poorly understood [1].

Core Architecture and Robustness Mechanisms of the ERN

Hierarchical Buffering Systems

The ERN exhibits remarkable resilience to genetic perturbation through multiple layers of functional cooperation and degeneracy among network components [1]. Systematic genetic perturbation studies disrupting 200 epigenetic regulator genes, individually or in combination, have revealed that robustness emerges from three primary buffering mechanisms:

Paralogous Compensation: Representing the first layer of functional compensation, where duplicated genes with retained overlapping function provide immediate backup. Key examples include ARID1A/ARID1B, CREBBP/EP300, KAT2A/KAT2B, and SUV39H1/SUV39H2 [1]. While loss of one paralogue is often tolerated—frequently selected for in cancer—combined loss of the gene pair has deleterious effects of varying magnitude, depending on context [1].

Degeneracy: Structurally distinct elements converging on common outputs, particularly prominent among histone modifiers where multiple enzymes share common substrates. For instance, several non-paralogous methyltransferases modify H3K36, and diverse COMPASS complexes methylate H3K4 [1]. Distinct modifications that induce similar biochemical effects on chromatin have evolved and often co-occupy genomic regions, such as multiple acetylated residues that decompact chromatin and correlate with transcriptional activity [1].

Parallel Pathways: Biochemically distinct routes leading to similar functional consequences, exemplified by gene silencing mediated through either DNA methylation or heterochromatin formation, with adaptor proteins like UHRF1 and KDM2B connecting these repression pathways [1].

Functional Network Topology

Network-wide maps of functional interactions reveal distinct connectivity patterns among epigenetic regulators. CREBBP cooperates with multiple acetyltransferases to form a subnetwork that ensures robust chromatin acetylation, while ARID1A interacts with regulators from across all functional classes, positioning it as a potential network hub [1]. This topological organization creates functional specialization within the broader network architecture, with certain nodes exhibiting broader connectivity than others.

Table 1: Layers of Robustness in the Epigenetic Regulatory Network

| Robustness Mechanism | Definition | Key Examples | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paralogous Compensation | Duplicated genes with retained overlapping function | ARID1A/ARID1B, CREBBP/EP300, KAT2A/KAT2B | Combined knockout shows synthetic lethality while single knockouts are viable [1] |

| Degeneracy | Structurally distinct elements converging on common outputs | Multiple H3K36 methyltransferases, diverse COMPASS complexes for H3K4 methylation | Non-paralogous enzymes can compensate for each other's loss [1] |

| Parallel Pathways | Biochemically distinct routes to similar functional outcomes | DNA methylation vs. heterochromatin formation for gene silencing | Simultaneous disruption of both pathways required for complete loss of silencing [1] |

Experimental Framework for ERN Mapping

Systematic Genetic Perturbation Strategies

Combinatorial genetic perturbation represents the gold standard for empirically determining ERN topology. The following protocol outlines a systematic approach for mapping functional interactions:

Experimental Workflow for Genetic Interaction Mapping:

Cell Line Selection and Engineering:

- Utilize somatic cells derived from normal epithelium of human tissues (e.g., HCEC-1CT, hTERT-HME1) to avoid confounding effects of pre-existing epigenetic alterations in cancer models [1].

- Generate doxycycline-inducible Cas9-expressing cells using the pCW-Cas9 lentiviral vector [1].

- Screen for high-activity clones responsive to 1 μg/ml doxycycline.

Combinatorial Genetic Perturbation:

- Design sgRNA libraries targeting 200+ epigenetic regulator genes.

- For individual knockouts: Transfert with single synthetic guide RNAs (sgRNAs) complexing CRISPR RNAs (crRNAs) with trans-activating CRISPR RNAs (tracrRNAs) at 20 nM concentration using Dharmafect4 or Lipofectamine 3000 [1].

- For combinatorial knockouts: Utilize multiple sgRNAs simultaneously or sequentially.

Phenotypic Assessment:

- Monitor somatic cell fitness through longitudinal growth assays.

- Assess epigenetic states via chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) for key histone modifications.

- Evaluate transcriptomic changes through RNA sequencing.

Genetic Interaction Analysis:

- Identify synthetic sick/lethal interactions by comparing observed double mutant phenotypes to expected values based on single mutant effects.

- Map functional interactions between gene pairs based on deviation from expected fitness.

Integrative Multi-Omics Network Reconstruction

Computational approaches that integrate multiple data types provide complementary methods for ERN inference. The SPIDER (Seeding PANDA Interactions to Derive Epigenetic Regulation) algorithm represents a advanced methodology for reconstructing gene regulatory networks using epigenetic data [2]:

SPIDER Workflow Protocol:

Input Data Preparation:

- Transcription Factor Motifs: Derive from position weight matrices (e.g., Cis-BP) mapped to reference genome using FIMO [2].

- Open Chromatin Regions: Process narrowPeak files from DNase-seq or ATAC-seq data [2].

- Gene Regulatory Regions: Define as 2kb windows centered around transcriptional start sites based on RefSeq annotations [2].

Seed Network Construction:

- Intersect transcription factor motif locations with open chromatin and gene regulatory regions.

- Construct bipartite network where edges represent transcription factors with motif locations overlapping both open chromatin and target gene regulatory regions.

- Degree-normalize edge weights to emphasize connections to high-degree transcription factors and genes.

Message-Passing Optimization:

- Apply PANDA (Passing Attributes between Networks for Data Assimilation) message-passing algorithm to harmonize connections across all transcription factors and genes [2].

- Iteratively refine network until edge weights stabilize.

Network Validation:

- Validate predictions using independently derived ChIP-seq data from ENCODE [2].

- Assess accuracy using Area Under the Receiver-Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC-ROC).

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for ERN Mapping

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Models | HCEC-1CT, hTERT-HME1 [ME16C] | Normal epithelial cells for physiological ERN studies | Prefer over cancer lines to avoid confounding epigenetic alterations [1] |

| Gene Editing | pCW-Cas9 lentiviral vector, synthetic gRNAs (crRNA + tracrRNA) | Combinatorial perturbation of epigenetic regulators | Use doxycycline-inducible system for temporal control; transfect at 20nM [1] |

| Epigenomic Profiling | CUT&Tag for histone modifications (H3K4me3, H3K27ac, etc.) | High-resolution chromatin state mapping | Superior signal-to-noise ratio vs. ChIP-seq; lower cell requirements [3] |

| Computational Tools | SPIDER, PANDA, ChromHMM | Network reconstruction from multi-omics data | Integrates motif, accessibility, and expression data [2] |

ERN Dysregulation in Disease and Therapeutic Targeting

Network Fragility in Disease States

While the ERN demonstrates remarkable robustness in physiological settings, accumulated epigenetic disorder in disease states creates synthetic fragilities. When combined with oncogene activation, epigenetic disorder exposes vulnerabilities and broadly sensitizes cells to further perturbation [1]. This principle is particularly evident in cancer, where:

- Oncogenic Signaling Impact: Oncogenic drivers such as KRAS, EGFR, and MYC induce genome-wide changes in chromatin and DNA methylation patterns in transformed cells [1].

- Mutation Accumulation: Additional epigenetic alterations superimpose during tumor progression due to interactions with tumor microenvironment and subclonal mutations frequently targeting epigenetic regulators [1].

- Network Collapse Threshold: The increased regulatory disorder impacts the network's ability to enact consistent function, creating vulnerabilities that may be exploited therapeutically [1].

Epigenetic Drug Development

Epigenetic drugs target key enzymes involved in epigenetic regulation to correct abnormal gene expression patterns, with several mechanistic classes:

- DNA Methyltransferase Inhibitors (DNMTi): Azacitidine and decitabine block DNMT activity, leading to reactivation of silenced genes through passive demethylation during DNA replication [4].

- HDAC Inhibitors: Vorinostat and romidepsin prevent removal of acetyl groups from histones, maintaining open chromatin structure that facilitates transcription [4].

- Emerging Targets: BET bromodomain inhibitors and other novel targets addressing non-coding RNAs and specific chromatin remodelers [4].

Network-based drug discovery approaches have identified promising repurposing candidates, including vorinostat (HDAC1 inhibitor) and sivelestat (ELANE inhibitor) for multiple sclerosis, demonstrating how ERN analysis can reveal therapeutic opportunities [5].

Advanced Techniques and Future Directions

Single-Cell and Dynamic ERN Mapping

Emerging technologies enable unprecedented resolution for studying ERN dynamics:

- Single-Cell Multi-Omics: Simultaneous measurement of chromatin accessibility, DNA methylation, and transcriptome in individual cells reveals cell-to-cell heterogeneity in ERN states.

- Time-Resolved Epigenomics: Longitudinal tracking of histone modification dynamics during critical transitions (e.g., embryonic development, cellular differentiation) using CUT&Tag profiling across multiple time points [3].

- Live-Cell Imaging: CRISPR-based imaging systems for visualizing chromatin dynamics in real-time.

Integration with Three-Dimensional Genome Architecture

The three-dimensional organization of the genome represents a critical component of the ERN that remains underexplored in network models:

- Chromatin Conformation Capture: Integration of Hi-C, ChIA-PET, and related methods to incorporate spatial constraints into ERN models.

- Loop Extrusion Dynamics: Modeling the impact of cohesin and CTCF on ERN function and gene regulation.

- Nuclear Compartmentalization: Accounting for the spatial organization of epigenetic modifications within the nucleus.

The field of epigenetic therapy is rapidly evolving, with promising developments extending beyond oncology into neurodegenerative, cardiovascular, and autoimmune diseases [4]. Advances in understanding epigenetic mechanisms and their role in diverse pathologies are driving the next generation of therapies designed to modulate network states rather than individual targets.

Defining the Epigenetic Regulatory Network requires moving beyond the characterization of isolated modifications to understanding the system-level properties that emerge from interactions between hundreds of epigenetic regulators. The ERN's robustness stems from multiple layers of functional cooperation and degeneracy, yet this robustness can be compromised in disease states, creating therapeutic opportunities. Advanced methodologies combining systematic genetic perturbation, multi-omics integration, and computational modeling provide powerful approaches for mapping ERN architecture and dynamics. As these technologies mature, they will enable increasingly precise modulation of epigenetic networks for therapeutic benefit across a wide spectrum of diseases.

The epigenetic regulatory network (ERN) represents the interconnected system of proteins and pathways that establish, maintain, and modulate chromatin and DNA methylation landscapes to control functional genome output. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical guide to the ERN's core components—writers, erasers, readers, and movers—and their cooperative functions in defining cellular states. We examine how functional redundancy and degeneracy within the ERN confer remarkable resilience to genetic perturbation in normal somatic cells, while accumulated epigenetic disruptions in disease states create novel therapeutic vulnerabilities. Detailed experimental methodologies for systematic ERN interrogation are presented, alongside emerging research tools and visualization frameworks that enable targeted investigation of epigenetic regulatory mechanisms. Understanding these core components and their interactions provides critical insights for exploiting epigenetic networks in therapeutic development.

The epigenetic regulatory network (ERN) comprises the complex, interconnected system of proteins and biochemical pathways that govern the establishment, maintenance, and dynamic modulation of chromatin structure and DNA methylation patterns [1]. This network controls the functional output of the genome by integrating multiple regulatory layers including reversible covalent modifications of DNA and histones, histone variants, chromatin remodeling, and higher-order chromatin compaction [1]. The ERN defines cellular states and behaviors through its coordinated regulation of gene expression profiles and maintenance of genome integrity.

Molecular control within the ERN is distributed across hundreds of proteins with diverse functions that cooperate to build a resilient regulatory system [1]. While individual epigenetic pathways have been extensively characterized, understanding how different classes of epigenetic regulators interact to form a robust network remains a fundamental challenge in epigenetics. Emerging research demonstrates that the ERN exhibits system-level properties including robustness and bistability of its outputs, ensuring consistent genome function across environmental fluctuations and internal perturbations [1]. This robustness emerges from multiple layers of functional cooperation and degeneracy among network components, creating both challenges and opportunities for therapeutic intervention.

Core ERN Components: Molecular Mechanisms and Functions

The ERN operates through four principal classes of components that execute distinct biochemical functions: writers that deposit epigenetic marks, erasers that remove them, readers that interpret them, and movers that reposition nucleosomes. The coordinated activity of these components establishes and maintains the epigenetic landscape.

Writers: Establishing Epigenetic Marks

Writers are enzymes that catalyze the addition of covalent modifications to DNA and histone proteins. These enzymes establish the chemical signals that constitute the epigenetic code, including DNA methylation patterns and post-translational modifications of histone tails.

DNA Methyltransferases (DNMTs): These writers catalyze the transfer of methyl groups to cytosine bases, primarily at CpG islands, forming 5-methylcytosine (5mC) [6]. DNMT1 maintains methylation patterns during DNA replication, while DNMT3A and DNMT3B establish de novo methylation patterns. DNA methylation typically creates a transcriptionally repressive environment by recruiting proteins that promote chromatin compaction [6].

Histone Acetyltransferases (HATs): HATs, including CREBBP/EP300 and KAT2A/KAT2B, catalyze the transfer of acetyl groups to lysine residues on histone tails [1] [6]. This neutralizes the positive charge of histones, reducing their affinity for DNA and promoting an open chromatin state permissive for transcription. CREBBP exemplifies functional cooperation within the ERN, forming a subnetwork with multiple acetyltransferases to ensure robust chromatin acetylation [1].

Histone Methyltransferases (HMTs): HMTs catalyze the methylation of lysine and arginine residues on histones. These include SUV39H1/SUV39H2 (H3K9 methylation), EZH2 (H3K27 methylation), and COMPASS family complexes (H3K4 methylation) [1] [6]. The functional outcome of histone methylation depends on the specific residue modified and the degree of methylation (mono-, di-, or tri-methylation).

Novel Histone Modification Writers: Recent research has identified writers for novel histone modifications including citrullination, crotonylation, succinylation, propionylation, butyrylation, 2-hydroxyisobutyrylation, and 2-hydroxybutyrylation [6]. These expanding modification types significantly increase the complexity of the histone code.

Erasers: Removing Epigenetic Marks

Erasers are enzymes that remove covalent modifications from DNA and histones, enabling dynamic regulation of epigenetic states. These components provide reversibility essential for epigenetic plasticity during cellular differentiation and environmental adaptation.

Ten-Eleven Translocation (TET) Enzymes: TET enzymes catalyze the iterative oxidation of 5mC to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), 5-formylcytosine (5fC), and 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC) [6]. This process initiates DNA demethylation pathways, both passive (replication-dependent) and active (replication-independent), leading to transcriptional activation of affected genes.

Histone Deacetylases (HDACs): HDACs remove acetyl groups from histone lysine residues, restoring the positive charge and promoting chromatin compaction [6]. This typically results in transcriptional repression. HDACs function as critical regulators of gene expression networks, and their inhibition can reactivate silenced tumor suppressor genes.

Histone Demethylases (KDMs): KDMs catalyze the removal of methyl groups from histone lysine and arginine residues. The LSD1 and Jumonji families of demethylases target specific methylation states with precise specificity [6]. Their activity enables dynamic regulation of histone methylation patterns in response to cellular signals.

Readers: Interpreting Epigenetic Signals

Readers are protein domains that recognize and bind to specific epigenetic modifications, translating the chemical signals into functional biological outcomes through recruitment of effector complexes.

Methyl-CpG-Binding Domain (MBD) Proteins: MBD proteins, including MECP2, MBD1, and MBD2, recognize and bind to methylated CpG dinucleotides [6]. These readers recruit additional cofactors such as HDACs and chromatin remodeling complexes to methylated DNA, facilitating the formation of transcriptionally repressive heterochromatin.

Bromodomains: These structural motifs recognize and bind to acetylated lysine residues on histones [6]. Proteins containing bromodomains, such as those in the SWI/SNF and BET families, often function as transcriptional co-activators that promote gene expression by recruiting additional transcription machinery.

Chromodomains and Tudor Domains: These specialized domains recognize methylated lysine residues on histones with specificity for both the modified residue and methylation state [6]. For example, HP1 proteins use chromodomains to bind H3K9me3, facilitating heterochromatin formation and spread.

Movers: Remodeling Chromatin Structure

Movers comprise ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes that physically reposition, eject, or restructure nucleosomes, altering chromatin accessibility without modifying the chemical properties of histones.

SWI/SNF Complexes: These multi-subunit complexes, including cBAF, PBAF, and ncBAF variants, utilize ATP hydrolysis to slide, evict, or restructure nucleosomes [1] [6]. SWI/SNF complexes represent a prototypical example of degeneracy within the ERN, with 29 protein subunits assembling in various combinations to exert partly overlapping functions in transcription regulation and genome maintenance [1]. Components like ARID1A function as functional hubs, interacting with regulators across all functional classes within the ERN [1].

ISWI Complexes: ISWI family remodelers regulate nucleosome spacing and facilitate the assembly of chromatin higher-order structure, often promoting chromatin compaction [6].

CHD Complexes: CHD remodelers typically slide nucleosomes and can contain additional chromatin-binding domains that recognize specific histone modifications [6].

INO80 Complexes: INO80 family remodelers specialize in histone variant exchange, such as replacing H2A with H2A.Z, and play roles in DNA repair and transcription [6].

Table 1: Core ERN Component Classes and Representative Examples

| Component Class | Biochemical Function | Representative Examples | Primary Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Writers | Deposit covalent modifications | DNMTs, HATs (CREBBP/EP300), HMTs (EZH2, SUV39H1) | Establish epigenetic marks that define chromatin states |

| Erasers | Remove covalent modifications | TET enzymes, HDACs, KDMs (LSD1, JMJC family) | Enable dynamic regulation and reversibility of epigenetic states |

| Readers | Recognize specific modifications | MBD proteins, Bromodomains, Chromodomains | Translate epigenetic marks into functional biological outcomes |

| Movers | Reposition nucleosomes | SWI/SNF, ISWI, CHD, INO80 complexes | Alter chromatin accessibility and architecture |

ERN Robustness: Functional Redundancy and Compensation Mechanisms

The ERN exhibits remarkable resilience to genetic perturbation through multiple layers of functional redundancy and compensation. Systematic genetic studies demonstrate that most individual epigenetic regulators are dispensable for somatic cell fitness, with robustness emerging from cooperative interactions among network components [1].

Paralogous Redundancy

Gene duplication has created numerous paralogue pairs within the ERN that provide a first layer of functional compensation [1]. Key examples include:

- ARID1A/ARID1B: SWI/SNF complex subunits with overlapping functions in chromatin remodeling

- CREBBP/EP300: Histone acetyltransferases with conserved catalytic activities

- KAT2A/KAT2B: Additional acetyltransferases with complementary functions

- SUV39H1/SUV39H2: H3K9 methyltransferases involved in heterochromatin formation

While individual loss of these paralogues is typically tolerated in normal cells—and frequently selected for in cancer—combined disruption of gene pairs produces deleterious effects of varying magnitude depending on cellular context [1].

Degeneracy and Convergent Function

Beyond structural homology, the ERN exhibits extensive degeneracy—structurally distinct elements that converge on common functional outputs [1]. This is particularly evident among histone modifiers, where multiple non-paralogous enzymes target identical substrates. For example, various COMPASS complexes methylate H3K4, while multiple methyltransferases modify H3K36 [1]. Additionally, distinct modifications that induce similar biochemical effects (e.g., multiple acetylated residues that decompact chromatin) often co-occur in genomic regions associated with transcriptional activity.

Parallel Pathways and Network Buffering

Robustness further emerges from parallel pathways that achieve similar functional outcomes through distinct biochemical routes [1]. Gene silencing provides a paradigm: repression can be mediated by DNA methylation through DNMTs or by heterochromatin formation through polycomb repressor complexes (PRC1 and PRC2) [1]. Adaptor proteins like UHRF1 (binding repressive histone marks and recruiting DNMTs) and KDM2B (recognizing CpG islands and recruiting PRC1) connect these pathways, creating integrated buffering mechanisms [1].

Table 2: Layers of Robustness in the Epigenetic Regulatory Network

| Robustness Mechanism | Definition | ERN Examples | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paralogous Redundancy | Functional overlap between gene duplicates | ARID1A/ARID1B, CREBBP/EP300, KAT2A/KAT2B | Individual knockout tolerated; combined knockout deleterious [1] |

| Degeneracy | Structurally distinct elements with convergent function | Multiple H3K4 methyltransferases (COMPASS family) | Independent enzymes maintain H3K4 methylation when others are impaired [1] |

| Parallel Pathways | Distinct biochemical routes to similar functional outcomes | DNA methylation vs. polycomb-mediated silencing | Both pathways maintain repression; combined disruption required for gene reactivation [1] |

| Inter-class Cooperation | Functional compensation across different component classes | ARID1A interactions across writer, eraser, reader classes | ARID1A-deficient cells show broad functional interactions across ERN [1] |

Experimental Approaches for ERN Investigation

Systematic interrogation of the ERN requires combinatorial approaches that assess individual and combined perturbations across network components. The following methodologies enable comprehensive mapping of functional interactions within the epigenetic regulatory system.

Systematic Genetic Perturbation Screening

Objective: To identify functional interactions and compensation mechanisms across the ERN through combinatorial genetic disruption.

Protocol Details:

Cell Model Establishment:

- Utilize somatic cells derived from normal human epithelium (e.g., HCEC-1CT colonic epithelial cells, hTERT-HME1 mammary epithelial cells) to minimize confounding effects of pre-existing epigenetic alterations in cancer models [1].

- Generate doxycycline-inducible Cas9-expressing clones through lentiviral transduction with pCW-Cas9 vector and monoclonal selection [1].

- Pre-treat with 1 μg/ml doxycycline for 24 hours to induce Cas9 expression prior to transfection.

Combinatorial Genetic Perturbation:

- Target 200+ epigenetic regulator genes individually and in combination using synthetic guide RNAs (sgRNAs) [1].

- Complex CRISPR RNAs (crRNAs) with trans-activating crRNAs (tracrRNAs) to form specific gRNAs at 20 nM concentration.

- Perform reverse transfection using Dharmafect4 (HME1 cells) or Lipofectamine 3000 (HCEC-1CT cells) [1].

- Replace growth medium after 24 hours.

Validation and Functional Assessment:

- After 72 hours, sort individual cells into multiwell plates using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (e.g., MoFlo XDP cell sorter) to generate monoclonal populations [1].

- Screen clonal populations by immunofluorescence and functional assays for epigenetic modifications.

- Assess cell fitness, proliferation, and global epigenetic changes through high-content imaging, RNA sequencing, and epigenomic profiling.

Epigenome Editing with CRISPR-dCas9 Systems

Objective: To causally investigate specific epigenetic modifications at defined genomic loci.

Protocol Details:

dCas9-Effector Fusion Design:

Targeting Strategy:

- Design sgRNAs with complementary sequences to target genomic loci of interest.

- Consider chromatin accessibility and nucleosome positioning when selecting target sites within regulatory regions.

Delivery and Validation:

- Deliver dCas9-effector and sgRNA constructs via lentiviral transduction or lipid nanoparticles.

- Assess epigenetic modifications at target loci through bisulfite sequencing (DNA methylation), chromatin immunoprecipitation (histone modifications), or targeted sequencing approaches.

- Monitor downstream transcriptional effects via RT-qPCR or RNA sequencing.

Multi-omics Integration for ERN Mapping

Objective: To identify core epigenetic regulators and their functional interactions through integrated analysis of multiple molecular layers.

Protocol Details:

Data Generation:

- Perform whole-genome bisulfite sequencing for DNA methylation patterns.

- Conduct chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) for histone modifications and transcription factor binding.

- Implement assay for transposase-accessible chromatin with sequencing (ATAC-seq) for chromatin accessibility.

- Generate RNA sequencing data for transcriptional outputs.

Spatial Multi-omics:

- Apply emerging spatial technologies to preserve architectural context of epigenetic regulation [6].

- Correlate epigenetic states with spatial organization in tissue microenvironments.

Computational Integration:

- Employ network analysis algorithms to identify functional hubs within the ERN.

- Develop machine learning models to predict vulnerability points based on multi-omics features.

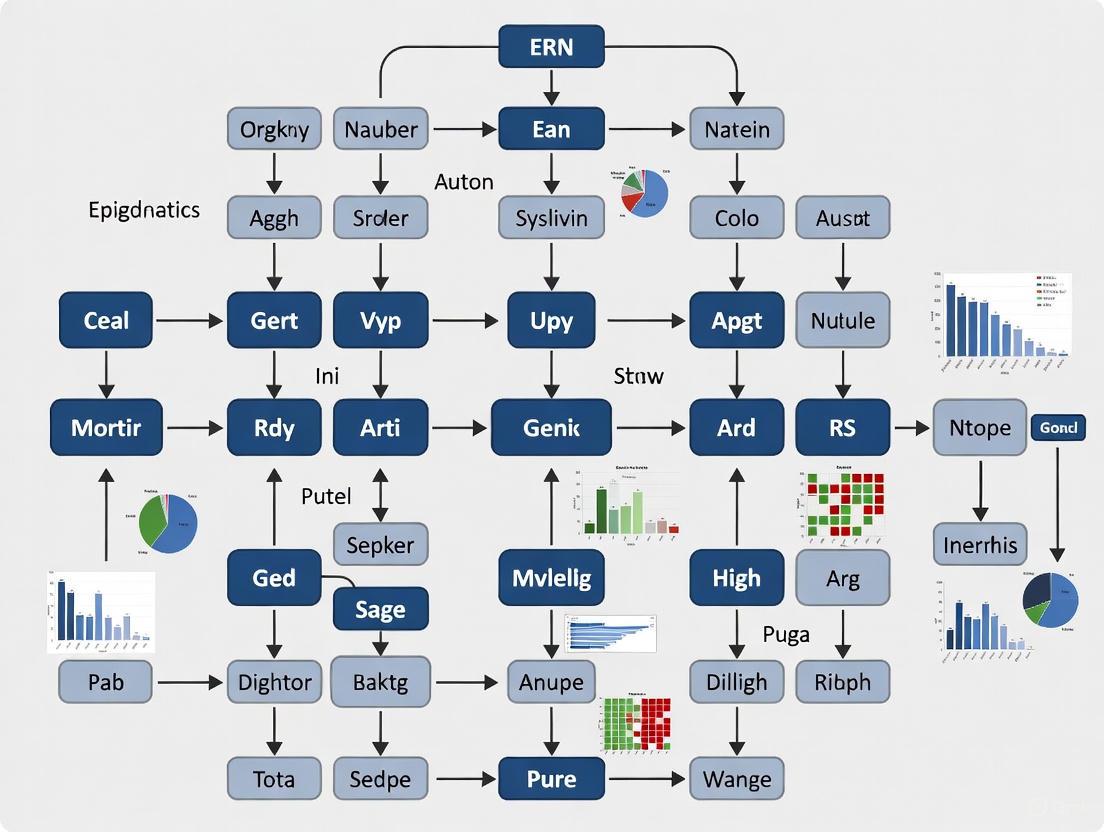

Diagram 1: ERN Component Interactions and Robustness Mechanisms. Core components (writers, erasers, readers, movers) regulate molecular features (DNA methylation, histone modifications, chromatin accessibility) that collectively control gene expression. Dashed lines indicate robustness mechanisms that provide functional backup.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for ERN Investigation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Screening Tools | pCW-Cas9 (doxycycline-inducible), sgRNA libraries targeting 200+ ERGs | Systematic genetic perturbation of epigenetic regulators | Functional interaction mapping in normal somatic cells [1] |

| Epigenome Editors | dCas9-DNMT3A, dCas9-TET1, dCas9-p300, dCas9-HDAC | Targeted manipulation of specific epigenetic marks at defined loci | Causal investigation of epigenetic modifications [7] [6] |

| Cell Model Systems | HCEC-1CT (colon epithelial), hTERT-HME1 (mammary epithelial) | Normal somatic cells with intact epigenetic networks | Physiological ERN studies minimizing cancer context confounders [1] |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors | HDAC inhibitors, BET bromodomain inhibitors, EZH2 inhibitors | Chemical perturbation of specific epigenetic regulators | Therapeutic targeting and functional validation [7] [6] |

| Multi-omics Platforms | Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing, ChIP-seq, ATAC-seq, spatial transcriptomics | Comprehensive mapping of epigenetic states and transcriptional outputs | Systems-level ERN analysis and biomarker discovery [6] |

Clinical Implications and Therapeutic Opportunities

Progressive accumulation of epigenetic alterations represents a hallmark of various diseases, particularly cancer, where approximately 30% of epigenetic regulators show broad loss-of-function [1] [7]. While the ERN maintains robustness in normal cells, accumulated epigenetic disorder in transformed cells creates novel vulnerabilities that can be exploited therapeutically.

Synthetic Lethality in Epigenetically Disrupted Cells

Cancer cells harboring mutations in specific ERN components often develop selective dependencies on backup regulators, creating opportunities for synthetic lethal approaches [1]. For example, ARID1A-deficient cells display broad sensitization to further perturbation, exposing synthetic fragilities that can be targeted pharmacologically [1]. The presence of known oncogenic drivers alongside epigenetic regulator loss significantly increases epigenetic fragility, potentially contributing to tumorigenesis while offering therapeutic windows [1].

Epigenetic Therapy Combinations

Single-agent epigenetic therapies often face limitations due to ERN robustness mechanisms [6]. However, rational combination strategies show significant promise:

- DNMT inhibitors + HDAC inhibitors: Dual targeting of DNA methylation and histone acetylation pathways

- EZH2 inhibitors + immunotherapy: Enhancing immune recognition through altered transcriptional programs

- BET inhibitors + targeted therapies: Overcoming resistance pathways in oncogene-driven cancers The integration of multi-omics technologies enables identification of core epigenetic drivers within complex networks, facilitating precision approaches to epigenetic therapy [6].

Diagram 2: ERN Dysregulation in Cancer and Therapeutic Strategies. Accumulated epigenetic disorder in cancer cells creates network fragility and synthetic lethal opportunities that can be targeted through multiple therapeutic approaches.

The epigenetic regulatory network represents a highly robust system maintained through coordinated interactions among writers, erasers, readers, and movers. Understanding the core components of this network and their functional relationships provides critical insights into both normal cellular physiology and disease pathogenesis. While redundancy and degeneracy within the ERN present challenges for therapeutic intervention, they also create opportunities for selective targeting of epigenetically disrupted cells. Future research leveraging systematic perturbation approaches, multi-omics technologies, and spatial analysis methods will continue to reveal the organizational principles of the ERN, enabling more effective targeting of epigenetic mechanisms in disease treatment.

Interplay of DNA Methylation and Histone Modifications in Gene Silencing and Activation

The epigenetic regulatory network (ERN) represents the complex, interconnected system of proteins and pathways that govern the establishment, maintenance, and modulation of chromatin and DNA methylation landscapes, ultimately controlling the functional output of the genome in defining cellular states and behaviors [1]. This network exhibits remarkable robustness in normal cells, with substantial functional redundancy inbuilt to prevent network collapse through multiple layers of functional cooperation and degeneracy among its components [1]. The ERN integrates two primary epigenetic signaling systems: DNA methylation, which involves the covalent addition of a methyl group to cytosine bases primarily in CpG dinucleotides, and histone modifications, which encompass post-translational alterations to histone proteins including methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitylation [8] [9]. Rather than operating independently, these systems engage in sophisticated cross-regulatory interactions that establish stable transcriptional states essential for development, cellular differentiation, and tissue-specific gene expression patterns. When disrupted, this intricate interplay contributes to various disease states, including cancer and developmental disorders, making understanding of these mechanisms crucial for therapeutic development [7] [10].

Fundamental Mechanisms of Epigenetic Regulation

DNA Methylation: Writers, Erasers, and Readers

DNA methylation involves the covalent addition of a methyl group to the fifth carbon of cytosine bases (5-methylcytosine, 5mC), primarily within CpG dinucleotides [11]. This process is catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), with DNMT3A and DNMT3B responsible for de novo methylation, and DNMT1 maintaining methylation patterns during DNA replication [11]. Approximately 70-90% of CpG sites throughout the genome are typically methylated, while CpG islands—regions with high G+C content and dense CpG clustering—remain largely unmethylated, particularly when located near promoter regions [11]. DNA methylation generally correlates with transcriptional repression through several mechanisms: it can directly impede transcription factor binding, alter chromatin accessibility, and recruit methyl-DNA binding proteins (MBD family) that associate with complexes containing histone deacetylases (HDACs) to promote a repressive chromatin state [11].

Histone Modifications: The Complexity of the Histone Code

Histone modifications represent a complex signaling system that regulates DNA accessibility through post-translational modifications to histone proteins [8]. The nucleosome, consisting of an octamer of histone proteins (H2A, H2B, H3, and H4) around which DNA is wrapped, provides multiple sites for reversible modifications that influence chromatin structure and function [8] [9]. These modifications include acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitylation, and several more recently discovered modifications such as lactylation and citrullination [8] [9]. Unlike DNA methylation, histone modifications can be associated with either activation or repression depending on the specific modification, its location, and cellular context [8].

Table 1: Key Histone Modifications and Their Functional Associations

| Histone Modification | Function | Genomic Location |

|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 | Activation | Promoters, bivalent domains |

| H3K27ac | Activation | Enhancers, promoters |

| H3K9ac | Activation | Enhancers, promoters |

| H3K4me1 | Activation | Enhancers |

| H3K36me3 | Activation | Gene bodies |

| H3K27me3 | Repression | Promoters in gene-rich regions, developmental regulators |

| H3K9me3 | Repression | Satellite repeats, telomeres, pericentromeres |

| H3S10P | DNA replication | Mitotic chromosomes |

| γH2A.X | DNA damage | DNA double-strand breaks |

Histone acetylation generally promotes an open chromatin state by neutralizing the positive charge on lysine residues, reducing histone-DNA interactions, and allowing transcription factor binding [8]. This modification is dynamically regulated by histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs) [8]. Histone methylation exhibits greater complexity, with different residues and methylation states conferring distinct functional consequences. For example, H3K4me3 marks active promoters, H3K4me1 marks enhancers, H3K36me3 is found across transcribed gene bodies, while H3K27me3 and H3K9me3 are associated with transcriptional repression [8].

Mechanistic Interplay Between DNA Methylation and Histone Modifications

Hierarchical Relationships in Gene Silencing

The relationship between DNA methylation and histone modifications in establishing gene silencing states has been extensively investigated, with evidence supporting both directions of control. Some studies indicate that DNA methylation patterns can guide histone modifications during gene silencing. For instance, methylated DNA is recognized by MBD family proteins that recruit complexes containing histone modifiers such as HDACs and histone methyltransferases, thereby promoting repressive histone marks [10] [11]. This relationship is exemplified by the interaction between MBD1 and the H3K9 methyltransferase Suv39h1, which enhances MBD1-mediated transcriptional repression [11].

Conversely, other studies demonstrate that histone modification states can direct DNA methylation patterns. The repressed erythroid-specific carbonic anhydrase II (CAII) promoter exhibits a bipartite epigenetic organization where active histone modifications (H3/H4 acetylation and H3K4me3) are localized around the transcription start site, while high levels of CpG methylation are present directly upstream from these active marks [12]. This configuration suggests that active histone modifications may prevent the spreading of CpG methylation toward the promoter core, demonstrating that repressive DNA methylation immediately adjacent to a promoter does not necessarily repress transcription [12]. This challenges the conventional view that promoter-proximal DNA methylation universally correlates with transcriptional silencing.

Table 2: Experimental Evidence for Hierarchical Relationships in Epigenetic Silencing

| Experimental System | Key Finding | Hierarchical Relationship | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| p16INK4a tumor suppressor | Histone modifications (H3K9 methylation) occurred prior to DNA methylation during silencing | Histone modifications → DNA methylation | [13] |

| Carbonic anhydrase II (CAII) promoter | Active histone modifications prevent spreading of adjacent DNA methylation | Histone modifications → DNA methylation boundary | [12] |

| MBD1-Suv39h1 interaction | Methylated DNA recruits histone methyltransferase | DNA methylation → Histone modifications | [11] |

| Neurospora crassa (dim5 mutant) | Loss of histone methyltransferase eliminates DNA methylation | Histone modifications → DNA methylation | [14] |

Context-Dependent Interactions in Facultative Heterochromatin

The interplay between DNA methylation and histone modifications exhibits significant context dependency, particularly in facultative heterochromatin marked by H3K27me3. Recent single-cell multi-omic technology (scEpi2-seq) that simultaneously profiles DNA methylation and histone modifications has revealed that differentially methylated regions demonstrate independent cell-type regulation in addition to H3K27me3 regulation, indicating that CpG methylation acts as an additional layer of control in facultative heterochromatin [15]. This simultaneous profiling has enabled direct observation of how specific histone modification contexts correlate with DNA methylation patterns, showing that regions marked by repressive histone modifications (H3K27me3 and H3K9me3) exhibit much lower DNA methylation levels (8-10%) compared to regions marked by the active mark H3K36me3 (50%) [15].

Advanced Methodologies for Studying Epigenetic Interplay

Single-Cell Multi-Omic Profiling Technologies

Traditional methods for studying DNA methylation and histone modifications typically require separate experiments using techniques such as bisulfite sequencing (for DNA methylation) and chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq, for histone modifications). However, the recent development of single-cell Epi2-seq (scEpi2-seq) enables joint readout of histone modifications and DNA methylation in the same single cell, providing unprecedented insight into the dynamics of epigenetic interactions [15]. This method leverages TET-assisted pyridine borane sequencing (TAPS) for bisulfite-free methylation detection while simultaneously using antibody-tethered micrococcal nuclease (MNase) to profile histone modifications [15].

The scEpi2-seq workflow begins with cell permeabilization and antibody binding to specific histone modifications, followed by single-cell sorting into 384-well plates. MNase digestion is then initiated by calcium addition, and the resulting fragments are processed with adaptor ligation containing cellular barcodes. The material undergoes TAPS conversion, where methylated cytosine is converted to uracil while leaving barcoded adaptors intact. Following library preparation and sequencing, both histone modification positions (from read mapping) and DNA methylation status (from C-to-T conversions) are extracted from the same single cell [15]. Application of this technology in K562 cells has demonstrated high-quality data with over 50,000 CpGs detected per single cell and high specificity (FRiP scores of 0.72-0.88) for histone modification profiling [15].

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Methodologies

Chromatin immunoprecipitation remains a cornerstone technique for investigating histone modifications and protein-DNA interactions. The standard ChIP protocol involves cross-linking proteins to DNA using formaldehyde, followed by chromatin fragmentation typically through sonication or enzymatic digestion [12] [8]. Specific antibodies against histone modifications of interest are used to immunoprecipitate the bound chromatin, after which the cross-links are reversed and the associated DNA is purified for sequencing analysis [8].

Quantitative ChIP protocols incorporate rigorous normalization procedures, including input controls and formula-based calculations: [%ChIP/input] = [E(Ctinput-CtChIP) * 100%], where E represents primer efficiency [12]. For sequential ChIP (reChIP) experiments, mononucleosomal chromatin preparation is optimized through micrococcal nuclease digestion, typically using 200 units of MNase with digestion for 30 minutes at room temperature in the presence of 1mM CaCl₂ [12]. The resulting mononucleosomal fragments enable high-resolution mapping of histone modifications relative to nucleosome positioning.

Genetic Perturbation Strategies for ERN Mapping

Systematic genetic perturbation approaches have been developed to map functional interactions within the epigenetic regulatory network. These typically involve CRISPR-Cas9 mediated knockout of epigenetic regulator genes (ERGs), either individually or in combination, to assess their impact on cellular fitness and epigenetic states [1]. A key methodology utilizes doxycycline-inducible lentiviral Cas9 systems (e.g., pCW-Cas9) combined with synthetic guide RNAs targeting specific ERGs [1]. Following transfection and antibiotic selection, monoclonal cell lines are derived through single-cell sorting and validated using immunofluorescence and functional assays.

Large-scale genetic interaction mapping has revealed that the ERN exhibits extensive robustness through multiple compensatory mechanisms, including paralog redundancy (e.g., CREBBP/EP300, ARID1A/ARID1B), degeneracy (structurally distinct elements converging on common outputs), and parallel pathways (distinct biochemical routes to similar functional consequences) [1]. This robustness is progressively compromised in cancer cells, where accumulated epigenetic alterations create context-specific vulnerabilities that may be exploited therapeutically [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Experimental Tools for Epigenetic Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Example Specifications | Experimental Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-H3K4me3 Antibody | Marks active promoters | Abcam ab8580, 1μg per ChIP | Promoter-associated histone modification profiling |

| Anti-H3K27me3 Antibody | Identifies facultative heterochromatin | Upstate #07-449, 2μg per ChIP | Polycomb-mediated silencing studies |

| Anti-H3K9me3 Antibody | Detects constitutive heterochromatin | Gift from T. Jenuwein [#4861], 2μg per ChIP | Heterochromatin formation studies |

| Anti-Acetyl-Histone H3 | Recognizes hyperacetylated active chromatin | Upstate #06-942, 2μg per ChIP | Transcription activation analysis |

| Protein A/G–agarose | Immunoprecipitation of antibody-chromatin complexes | 33% slurry, 30μl per reaction | Chromatin immunoprecipitation |

| Micrococcal Nuclease (MNase) | Nucleosome positioning mapping | 200 units, 30min digestion at room temperature | Mononucleosomal chromatin preparation |

| pCW-Cas9 System | Doxycycline-inducible CRISPR-Cas9 | Lentiviral vector, 1μg/ml doxycycline induction | Epigenetic regulator gene knockout |

| TAPS Reagents | Bisulfite-free methylation sequencing | TET2, pyridine borane | scEpi2-seq methylation detection |

Implications for Disease and Therapeutic Development

Dysregulation of the interplay between DNA methylation and histone modifications contributes significantly to human diseases, particularly cancer. In cancer development, the epigenetic regulatory network undergoes substantial disruption, with broad loss of approximately 30% of epigenetic regulators globally within cancer cells [7]. This leads to aberrant transcriptional responses to stress and confers enhanced adaptive capacity over normal cells [7]. The accumulated epigenetic disorder in neoplastic cells creates synthetic fragilities and broadly sensitizes cells to further perturbation, potentially offering therapeutic opportunities [1].

Notably, histone fold mutations have been identified in approximately 7% of cancer patients, with H2B E76K being the most common mutation [7]. This mutation destabilizes the H2B/H4 interface, leading to increased chromatin accessibility and upregulation of key signaling pathways including polycomb-repressed regions, epithelial-mesenchymal transition pathways, and AKT and c-Jun signaling, collectively contributing to tumorigenesis [7]. Additionally, CTCF transcription factor binding site mutations occur with higher frequency at persistent CTCF binding sites in many cancers, disrupting higher-order chromatin architecture and contributing to oncogenic gene expression programs [7].

The interconnected nature of epigenetic regulatory mechanisms has inspired several therapeutic approaches:

- Combination epigenetic therapy targeting both DNA methylation and histone modifications

- Synthetic lethal approaches targeting compensatory pathways in epigenetically disrupted cancer cells

- Postbiotic therapy leveraging microbial metabolites with epigenetic modulatory activity

Interestingly, the microbiome has emerged as a significant modulator of epigenetic states, with specific bacterial species such as Faecalibaculum rodentium producing butyrate that functions as a histone deacetylase inhibitor, providing epigenetic modulation of cell apoptosis [7]. In colorectal cancer, the presence of intra-tumoral bacteria modulates treatment response, potentially through the production of soluble metabolites that regulate HLA expression and other epigenetically modulated pathways [7].

Future Directions and Concluding Perspectives

The field of epigenetic interplay continues to evolve rapidly with emerging technologies and conceptual frameworks. Single-cell multi-omic approaches are poised to reveal unprecedented detail about the dynamics and heterogeneity of epigenetic states in development and disease [15]. The application of artificial intelligence-based modeling to epigenetic data, particularly in clinical contexts such as liquid biopsy, represents a promising frontier for biomarker development and clinical translation [7]. Additionally, the systematic mapping of genetic interactions within the ERN provides a foundation for predicting synthetic lethal relationships that may be exploited therapeutically [1].

A critical emerging concept is that of the epigenetic regulatory network as an integrated system with properties that extend beyond the function of individual components. This network perspective helps explain how normal cells maintain epigenetic stability despite constant environmental fluctuations, and how this stability becomes compromised in disease states [1] [7]. The demonstrated bipartite organization of epigenetic marks at specific loci, with repressive DNA methylation existing adjacent to active histone modifications without necessarily repressing transcription, challenges simplified models of epigenetic regulation and highlights the context-dependent nature of these interactions [12].

As epigenetic therapies continue to advance, combination approaches that target multiple components of the ERN simultaneously may prove more effective than single-agent therapies. Furthermore, understanding the temporal dynamics of epigenetic changes during disease progression, particularly the transition to metastatic disease where epigenetic alterations may facilitate the necessary cellular adaptations, represents a crucial area for future investigation [7]. The integration of epigenetic profiling into clinical practice, particularly through non-invasive liquid biopsy approaches, holds significant promise for improving diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic monitoring across a range of human diseases.

The Role of Non-Coding RNAs and Chromatin Remodeling in Network Stability

The epigenetic regulatory network (ERN) represents a sophisticated, multi-layered system of interacting components that maintains cellular state stability through functional redundancy and compensatory mechanisms. Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) and ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes have emerged as critical players in this network, contributing significantly to its resilience. Recent research reveals that ncRNAs interact extensively with chromatin remodelers to fine-tune gene expression programs, while the ERN exhibits remarkable robustness to individual perturbations through paralog compensation, degeneracy, and parallel pathways. However, in disease states such as cancer, accumulated epigenetic alterations can push this network beyond its stability threshold, creating context-specific vulnerabilities. Understanding these interactions provides novel insights for therapeutic interventions targeting network fragility in human diseases.

The epigenetic regulatory network (ERN) comprises the interconnected system of proteins, RNAs, and pathways that govern the establishment, maintenance, and modulation of chromatin and DNA methylation landscapes. This network controls the functional output of the genome by integrating reversible covalent modifications of DNA and histones, histone variants, chromatin remodeling, and higher-order compaction [1]. The ERN exhibits emergent system-level properties including robustness and bistability, which ensure consistent genome function across environmental fluctuations and cellular divisions [1]. This robustness emerges from multiple layers of functional cooperation and degeneracy among network components, creating a resilient system that maintains cellular fitness despite perturbations [1].

Within this network framework, non-coding RNAs and chromatin remodeling complexes serve as critical nodes that influence network stability. ncRNAs, particularly long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), have shifted from the margins of molecular biology to the core of our understanding of gene regulation, cellular plasticity, and disease pathogenesis [16]. Similarly, ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes, especially the SWI/SNF family, function as central processors that interpret regulatory information and implement chromatin structural changes [17]. The interaction between these elements creates a dynamic control system that rewires cellular responses in development, stress, and pathology.

Non-Coding RNAs: Diverse Regulators in the ERN

Classification and Functional Mechanisms

Non-coding RNAs represent a heterogeneous class of RNA molecules that regulate gene expression without being translated into proteins. The major classes include:

- MicroRNAs (miRNAs): ~22 nucleotide transcripts that bind to complementary sequences on target mRNAs, leading to translational repression or mRNA degradation [18].

- Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs): Transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides that function through diverse mechanisms including chromatin remodeling, scaffolding of protein complexes, and regulation of transcription [19] [18].

- Circular RNAs (circRNAs): Covalently closed loop structures that function as microRNA sponges, transcriptional regulators, and protein scaffolds [16] [18].

Table 1: Major Non-Coding RNA Classes and Their Functions

| ncRNA Class | Size Range | Primary Functions | Subcellular Localization |

|---|---|---|---|

| miRNA | ~22 nucleotides | mRNA degradation, translational repression | Cytoplasm |

| lncRNA | >200 nucleotides | Chromatin remodeling, transcription regulation, molecular scaffolding | Nucleus, Cytoplasm |

| circRNA | Variable | miRNA sponging, protein scaffolding, translation | Cytoplasm |

| snoRNA | 60-300 nucleotides | rRNA modification, RNA processing | Nucleolus |

LncRNAs demonstrate particular functional diversity in their mechanisms of action. They can directly interact with chromatin-modifying enzymes and nucleosome-remodeling factors to control chromatin structure and accessibility of genetic information [20]. Rather than functioning as uniform molecular sponges, lncRNAs are now understood as diverse ribonucleoprotein scaffolds with defined subcellular localizations, modular secondary structures, and dosage-sensitive activities—often functioning at low abundance to achieve molecular specificity [16].

Regulatory Roles in Network Stability

ncRNAs contribute significantly to ERN stability through several key mechanisms:

- Network buffering: ncRNAs can compensate for genetic perturbations by providing alternative regulatory pathways. For instance, in somatic cells, most individual epigenetic regulators are dispensable for fitness due to functional compensation within the network [1].

- Context-dependent regulation: ncRNA effects are deeply dependent on cell type, developmental stage, metabolic state, and environmental stressors, allowing precise adjustment of network outputs without destabilization [16].

- Multi-target coordination: Single ncRNAs can regulate multiple nodes within a pathway simultaneously, as demonstrated by miR-142-3p, which coordinates YES1, TWF1, YAP1 phosphorylation, and autophagy pathways to overcome drug resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma [16].

The positioning of ncRNAs within the ERN allows them to function as integrative hubs that process multiple inputs and coordinate coherent outputs, thereby contributing to network stability despite fluctuating conditions or individual component failure.

Chromatin Remodeling Complexes: Architectural Engineers of the Genome

The SWI/SNF Complex and Its Functions

The SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex represents a prototypical example of an ATP-dependent chromatin remodeler that plays a central role in ERN stability. This complex contains a conserved DNA-dependent ATPase as its catalytic subunit (either BRM or BRG1) and distinct flanking domains that facilitate interactions with chromatin [17]. The SWI/SNF complex uses ATP hydrolysis to alter chromatin structure by sliding, ejecting, or restructuring nucleosomes, thereby controlling DNA accessibility [17].

The mechanism of SWI/SNF-mediated chromatin remodeling follows several models:

- Nucleosome sliding: The complex uses ATP hydrolysis to remodel histones, causing nucleosomes to slide along DNA and expose previously concealed regulatory elements [17].

- DNA bulging: SWI/SNF can push or pull linker DNA into nucleosome regions, creating DNA bulges that change histone-DNA interactions and increase DNA accessibility [17].

- Targeted recruitment: The complexes are recruited to specific genomic locations by transcriptional activators, transcription factors, or lncRNAs, ensuring precise spatial and temporal regulation [17].

Table 2: Subunits of SWI/SNF Chromatin Remodeling Complexes

| Subunit Type | Component Examples | Function | Complex Association |

|---|---|---|---|

| Catalytic ATPase | BRG1, BRM | ATP hydrolysis, nucleosome remodeling | BAF (BRG1/BRM), PBAF (BRG1 only) |

| Core subunits | BAF155, BAF170, SNF5 | Structural integrity, basic remodeling activity | BAF and PBAF |

| Signature subunits | BAF250A/B, BAF180, BAF200 | Complex specificity, target recognition | BAF (BAF250), PBAF (BAF180/200) |

| Accessory subunits | BAF57, BAF53A/B, BAF60A-C | Specialized functions, complex modulation | BAF and PBAF |

Robustness Mechanisms in Chromatin Remodeling Systems

Chromatin remodeling complexes contribute to ERN stability through several robustness mechanisms:

- Paralog compensation: Duplicated genes with overlapping functions, such as CREBBP/EP300 and ARID1A/ARID1B, provide buffer capacity where loss of one paralogue is tolerated while combined loss has deleterious effects [1].

- Degeneracy: Multiple structurally distinct complexes can perform similar functions. For example, various SWI/SNF assemblies (cBAF, PBAF, ncBAF) exert partly overlapping functions in transcription regulation and genome maintenance [1].

- Functional redundancy: Parallel pathways leading to similar functional outcomes exist, such as gene silencing mediated by either DNA methylation or heterochromatin formation [1].

These overlapping mechanisms ensure that the chromatin remodeling system maintains functionality despite component failures or environmental challenges, representing a fundamental stabilizing element within the broader ERN.

Integration of ncRNAs and Chromatin Remodeling in Network Stability

Molecular Interaction Mechanisms

The integration of ncRNAs with chromatin remodeling complexes creates sophisticated regulatory circuits that enhance ERN stability. Two primary interaction models have been identified:

- Binding Model: lncRNAs can directly bind to subunits of chromatin remodeling complexes, serving as guides to anchor them to specific genomic locations or functioning as decoys to sequester them from chromatin. For example, the lncRNA SChLAP1 directly binds to the hSNF5 subunit of the SWI/SNF complex, antagonizing its tumor suppressive functions by decreasing genomic binding [17].

- Recruitment Model: lncRNAs can recruit chromatin remodeling complexes to specific genomic loci, enabling targeted chromatin modifications. The lncRNA Mhrt protects against cardiac hypertrophy by directly binding to the Brg1 helicase domain, sequestering it from genomic DNA loci and inhibiting its gene regulatory functions [20].

These interaction modes allow for precise spatial and temporal control of chromatin remodeling activities, adding a layer of regulation that enhances network responsiveness while maintaining stability through controlled feedback mechanisms.

Network-Level Functional Consequences

The integration of ncRNAs with chromatin remodeling machinery has several network-level consequences:

- Distributed control: Regulatory control is distributed across multiple network nodes rather than concentrated at single points, reducing vulnerability to single-component failure.

- Feedback stabilization: ncRNAs can establish negative feedback loops that stabilize network outputs. For instance, Brg1 regulates the expression of many genes, including those encoding ncRNAs that can in turn regulate Brg1 activity [20].

- Context-dependent rewiring: The same ncRNA can participate in different regulatory modules depending on cellular context, allowing dynamic network reconfiguration without structural overhaul.

These properties enable the ERN to maintain functional outputs despite component variations, environmental fluctuations, or moderate levels of damage—key characteristics of a robust biological system.

Figure 1: ncRNA and Chromatin Remodeling Interactions in ERN Stability

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Systematic Genetic Perturbation Mapping

Comprehensive understanding of ERN stability requires systematic approaches to map functional interactions:

- Combinatorial mutagenesis screens: Simultaneous disruption of multiple epigenetic regulator genes reveals functional interactions and compensation mechanisms. A recent study disrupted 200 epigenetic regulator genes individually and in combination to generate network-wide maps of functional interactions [1].

- Network robustness assessment: Quantitative analysis of cellular fitness after progressive epigenetic perturbation determines the threshold for network collapse. Research shows normal cells tolerate loss of many individual regulators, but accumulated disorder in neoplastic cells creates synthetic fragility [1].

- Interaction mapping: Epistatic analyses identify redundancy by structural homology, degeneracy, or parallel pathways, clarifying buffering mechanisms upon perturbation [1].

Protocol: Systematic Genetic Perturbation of ERN Components

- Cell line selection: Utilize somatic cells derived from normal human epithelium (e.g., HCEC-1CT, hTERT-HME1) to minimize pre-existing epigenetic alterations [1].

- Cas9 system establishment: Transduce cells with doxycycline-inducible lentiviral Cas9 vector (e.g., pCW-Cas9) and select high-activity clones responsive to 1 μg/ml doxycycline [1].

- Combinatorial guide RNA design: Design synthetic guide RNAs (gRNAs) targeting individual or combined epigenetic regulator genes, complexing CRISPR RNAs (crRNAs) with trans-activating CRISPR RNAs (tracrRNAs) [1].

- Transfection optimization: Reverse transfect gRNAs at 20 nM concentration using appropriate transfection reagents (e.g., Dharmafect4 for HME1 cells, Lipofectamine 3000 for HCEC-1CT cells) [1].

- Monoclonal line generation: After 72 hours post-transfection, sort individual cells into multiwell plates using a cell sorter (e.g., MoFlo XDP) and raise clonal populations [1].

- Validation screening: Screen knockout efficiency by immunofluorescence or Western blot detecting target proteins (e.g., ARID1A, CREBBP) [1].

Network Reconstruction from Epigenetic Data

Computational approaches can reconstruct regulatory networks from epigenetic data:

- SPIDER algorithm: The Seeding PANDA Interactions to Derive Epigenetic Regulation (SPIDER) approach overlaps transcription factor motif locations with epigenetic data (open chromatin locations) and applies message-passing algorithms to construct gene regulatory networks [2].

- Multi-omic integration: Combine predicted transcription factor binding information with protein-protein interaction and gene co-expression data to estimate regulatory networks [2].

- Experimental validation: Use independently derived ChIP-seq data as "gold standard" networks to evaluate prediction accuracy [2].

Figure 2: SPIDER Network Reconstruction Workflow

ncRNA-Chromatin Interaction Mapping

Several specialized approaches can characterize interactions between ncRNAs and chromatin remodeling complexes:

- RNA-centric proteomics: Identify protein interaction partners of specific lncRNAs using techniques such as CHIRP-MS or RAP-MS.

- Chromatin localization: Determine genomic binding sites of chromatin-associated ncRNAs through ChIRP-seq or CHART-seq.

- Functional validation: Assess the functional consequences of ncRNA perturbation on chromatin states using RNAi or CRISPR-based approaches.

Protocol: Characterizing lncRNA-Chromatin Remodeler Interactions

- Identification of candidate lncRNAs: Screen for nuclear-enriched lncRNAs with expression patterns correlated with chromatin remodeling activity [20].

- Interaction validation: Employ RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) or crosslinking immunoprecipitation (CLIP) to verify direct binding between lncRNAs and chromatin remodeling subunits (e.g., Brg1) [20].

- Functional domain mapping: Use truncated lncRNA constructs to identify minimal functional domains required for interaction (e.g., Mhrt requires a specific region to bind Brg1's helicase domain) [20].

- Phenotypic rescue assays: Test whether wild-type versus mutant lncRNAs can rescue physiological phenotypes (e.g., Mhrt rescue of stress-induced cardiac hypertrophy) [20].

- Genomic binding assessment: Determine how lncRNA perturbation affects genome-wide distribution of chromatin remodelers using ChIP-seq [17].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for ncRNA-Chromatin Remodeling Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Inducible Cas9 System | Combinatorial gene knockout | pCW-Cas9 vector, 1 μg/ml doxycycline induction [1] |

| Synthetic Guide RNAs | Targeted gene disruption | 20 nM concentration, complexed crRNA:tracrRNA [1] |

| Chromatin Accessibility Assays | Mapping open chromatin regions | ATAC-seq, DNase-seq [2] |

| Position Weight Matrices | Transcription factor binding prediction | Cis-BP database, FIMO mapping [2] |

| Crosslinking Reagents | RNA-protein interaction capture | Formaldehyde, UV crosslinking [20] [17] |

| SPIDER Algorithm | Network reconstruction from epigenetic data | Integration of motif locations with open chromatin data [2] |

Quantitative Data Synthesis: Network Properties and Stability Metrics

Table 4: Quantitative Measures of ERN Stability and ncRNA Function

| Parameter | Measurement Approach | Representative Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Network robustness | Cellular fitness after ERG perturbation | Most individual epigenetic regulators dispensable in somatic cells; functional compensation observed [1] |

| Synthetic fragility | Fitness impact of combined perturbations | Accumulated epigenetic disorder in neoplastic cells exposes synthetic fragility [1] |

| Paralogue compensation | Viability after paralogue pair knockout | Combined loss of ARID1A/ARID1B or CREBBP/EP300 has deleterious effects [1] |

| ncRNA network influence | Multi-target coordination efficacy | miR-142-3p targets YES1 and TWF1, converging on YAP1 phosphorylation and autophagy [16] |

| Chromatin remodeler recruitment | Genomic binding upon ncRNA perturbation | SChLAP1 decreases SWI/SNF genomic binding, impairing tumor suppressive functions [17] |

The integration of non-coding RNAs and chromatin remodeling complexes within the epigenetic regulatory network creates a robust system that maintains cellular stability while allowing adaptive responses. The multilayered control systems built by these components rewire cells in development, stress, and pathology, with network robustness emerging from functional redundancy, paralog compensation, and degeneracy among components [16] [1].

Future research directions should focus on:

- Single-cell and spatial resolution: Applying single-cell and spatial transcriptomics with targeted RNA-protein crosslinking will sharpen causal maps of ncRNA activity in situ [16].

- Network fragility thresholds: Determining how much epigenetic disorder can be endured before network collapse, particularly in disease contexts [1].

- Therapeutic exploitation: Leveraging knowledge of ERN stability to develop treatments that specifically target network vulnerabilities in cancer cells while sparing normal cells [1] [7].

The coming decade will likely see principles of precision engineering applied to the complexity of RNA biology, potentially yielding novel therapeutic strategies that manipulate network stability for clinical benefit. As the field progresses, integrating mechanistic biology with data-driven network inference and engineering-oriented translational design will be essential for realizing the full potential of ncRNA and chromatin remodeling research.

Epigenetic Regulatory Networks (ERNs) represent the complex, interconnected system of chromatin modifiers, transcription factors, and signaling pathways that establish and maintain cellular identity. In multicellular organisms, pluripotent cells undergo differentiation into terminal fates through the adoption of characteristics necessary for specific cell type functions. Concomitant with this differentiation process, cells progressively lose their original plasticity, a phenomenon observed since early embryological experiments [21]. The molecular basis for this progressive restriction of cellular plasticity lies within the ERN framework, which governs both the adoption of specific fates and the restriction of alternative developmental pathways. Master regulatory transcription factors can reprogram cellular identity when ectopically expressed, but their effectiveness diminishes significantly in fully differentiated cells, demonstrating the strengthening of ERN stability over developmental time [21]. Understanding ERN plasticity—the dynamic interplay between stability and flexibility in cellular states—provides critical insights into normal development, disease pathogenesis, and potential therapeutic interventions, particularly in cancer where cellular plasticity contributes to drug resistance [22] [23].

Core Mechanisms of Cellular State Maintenance

Chromatin-Based Mechanisms of Fate Restriction

The maintenance of cellular state is enforced through multiple chromatin-based mechanisms that create a stable epigenetic landscape. Genes involved in the deposition and maintenance of histone marks associated with transcriptional repression, particularly H3K27 and H3K9 methylation, have been implicated in developmental fate restriction. Removal of the PRC2 component mes-2/E(z) extends the time period during which ectopic expression of fate-determining transcription factors like hlh-1 or end-1 results in aberrant adoption of alternative fates [21]. The histone chaperone lin-53, functioning as part of a complex with PRC2 components (MES-2/E(z), MES-3, and MES-6/ESC), is critical in maintaining cell fate restriction in germ cells. Additionally, the FACT chromatin chaperone complex and the chromodomain-containing gene mrg-1/MRG15 are necessary to restrict cell fate transformations [21]. These mechanisms collectively establish a chromatin environment that stabilizes transcriptional programs against stochastic fluctuations or external reprogramming signals.

Transcription Factor Networks in Fate Stabilization

Terminal selector-type transcription factors act in postmitotic cells to specify terminal identity while simultaneously restricting cellular plasticity. In C. elegans, for example, removal of various terminal selector TFs permits CHE-1-mediated cellular reprogramming, indicating their dual role in both directing fate adoption and maintaining fate restriction [21]. A detailed characterization of the terminal selector TF UNC-3 revealed cooperation with multiple chromatin remodeling factors, including the H3K9 methyltransferases MET-2 and SET-25, demonstrating coordinated action between differentiation factors and histone modifiers in stabilizing cellular identity [21]. This network architecture, where transcription factors both activate lineage-specific genes and recruit chromatin modifiers to repress alternative fates, creates a self-reinforcing regulatory circuit that maintains cellular state across cell divisions.

Table 1: Key Molecular Players in Cellular Fate Restriction

| Molecule/Complex | Molecular Function | Role in Fate Restriction |

|---|---|---|

| PRC2 complex (MES-2/3/6) | H3K27 methyltransferase | Represses alternative fate genes through H3K27me3 deposition |

| lin-53/RbAP46/48 | Histone chaperone | Facilitates PRC2-mediated repression in germ cells |

| MET-2/SET-25 | H3K9 methyltransferases | Establish heterochromatic regions to limit plasticity |

| Terminal selector TFs (e.g., UNC-3) | Sequence-specific transcription factors | Activate lineage-specific genes while recruiting repressive complexes |

| usp-48 | Ubiquitin hydrolase | Restricts cellular plasticity with tissue specificity |

| DOT-1.1 | H3K79 methyltransferase | Limits reprogramming capacity in differentiated cells |

Feedback Loops and Cellular Memory

Gene regulatory networks maintain cellular memory through feedback loop architectures that create bistable expression states. Positive autoregulation helps lock genes into active states, ensuring stability once a transcriptional state is established. Double positive feedback loops—where two genes mutually enhance each other's expression—are especially critical for maintaining bistable gene expression states that can persist through multiple cell divisions [23]. This cellular memory operates at the transcriptional level, with bistable configurations alternating between active ("on") and inactive ("off") modes to ensure essential gene expression patterns are maintained [23]. The mutual reinforcement within these feedback loops provides stability against random fluctuations in gene expression, although accumulated noise over successive cell divisions can eventually destabilize this memory [23].

ERN Dynamics in Cellular Differentiation and Reprogramming

Progressive Restriction of Plasticity During Development