Epigenetic Mechanisms in Neurodevelopmental Disorders: From Molecular Pathways to Clinical Translation

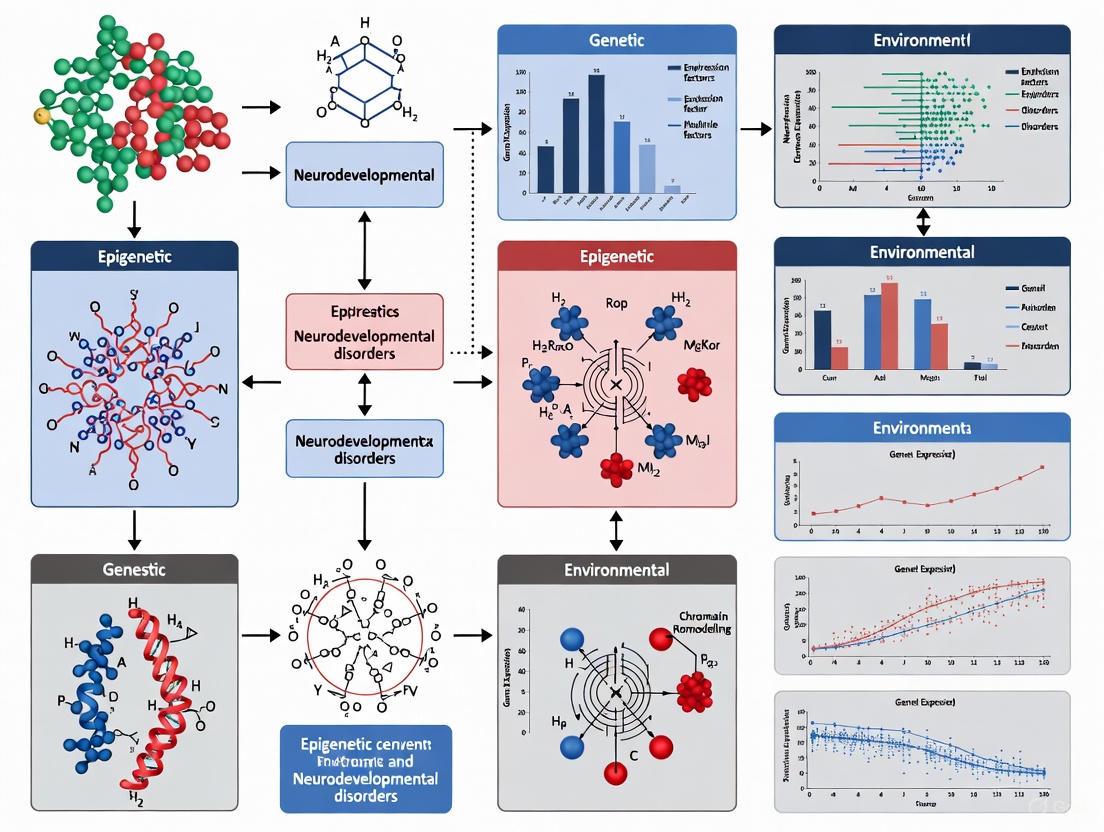

This review synthesizes current research on the critical role of epigenetic mechanisms—including DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNAs—in the pathogenesis of neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs).

Epigenetic Mechanisms in Neurodevelopmental Disorders: From Molecular Pathways to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This review synthesizes current research on the critical role of epigenetic mechanisms—including DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNAs—in the pathogenesis of neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs). We explore how genetic and environmental factors converge on the epigenome to disrupt typical brain development, leading to conditions such as autism spectrum disorder, Rett syndrome, and intellectual disability. The article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals, covering foundational biology, advanced methodological approaches for biomarker discovery, challenges in therapeutic development, and the validation of epigenetic signatures for early risk detection. Finally, we discuss the promising transition of epigenetic research into novel diagnostic tools and targeted therapeutic interventions, framing the future of precision medicine for NDDs.

The Epigenetic Landscape of the Developing Brain: Core Mechanisms and Pathogenic Disruption

Epigenetics is the study of heritable changes in gene expression that do not involve alterations to the underlying DNA sequence [1] [2]. These mechanisms act as a critical interface between the static genome and a dynamic environment, allowing the adaptation of genetic instruction across an organism's lifespan and are particularly crucial for complex processes like brain development [3] [4]. The mammalian brain undergoes a tightly orchestrated series of developmental steps, including progenitor proliferation, neuronal migration, and the establishment of synaptic connections [4]. Disruptions to these processes, mediated by genetic or epigenetic dysregulation, can lead to a variety of neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs), such as autism spectrum disorders (ASD), epilepsy, and intellectual disabilities [3] [4]. This review provides an in-depth technical guide to the three core epigenetic mechanisms—DNA methylation, histone modifications, and chromatin remodeling—and frames their functions within the context of NDD research.

DNA Methylation

Molecular Basis and Dynamics

DNA methylation is a reversible epigenetic mark involving the covalent addition of a methyl group to the 5-carbon of a cytosine residue, primarily within CpG dinucleotides, forming 5-methylcytosine (5mC) [5] [6]. This process is catalyzed by enzymes called DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs). DNMT3A and DNMT3B are responsible for de novo methylation, establishing new methylation patterns, while DNMT1 acts as a maintenance methyltransferase, copying existing methylation patterns to the daughter strand during DNA replication [5]. The discovery of TET proteins, which catalyze the oxidation of 5mC to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) and further derivatives, revealed an active pathway for DNA demethylation [2]. Notably, 5hmC is not merely an intermediate but is particularly abundant in the brain and is often associated with active transcription [6] [2].

The functional outcome of DNA methylation is highly context-dependent. Generally, methylation within gene promoter regions is associated with transcriptional repression, potentially by preventing transcription factor binding or recruiting proteins that recognize methylated DNA, such as the methyl-CpG-binding domain (MBD) family [5] [6]. In contrast, methylation within gene bodies is often linked to active transcription [5].

Technical Analysis and Key Methodologies

Investigating DNA methylation requires specialized techniques, with bisulfite sequencing being the gold standard. Treatment of DNA with bisulfite converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils (which are read as thymines in sequencing), while methylated cytosines remain unchanged, allowing for single-base-pair resolution mapping of 5mC [7]. Advanced methods now allow for this analysis at the single-cell level (scBS-seq) [7]. An emerging alternative is TET-assisted pyridine borane sequencing (TAPS), which offers a less destructive approach by converting methylated cytosine to uracil while leaving the adaptors intact, making it particularly suitable for single-cell multi-omics [7].

Table 1: Key Enzymes and Proteins in DNA Methylation

| Protein/Enzyme | Primary Function | Relevance to NDDs |

|---|---|---|

| DNMT1 | Maintenance methylation during DNA replication | Altered expression linked to spermatogenic failure; potential model for neuronal dysfunction [5]. |

| DNMT3A/B | De novo methylation during development | Crucial for brain development; mutations associated with neurodevelopmental syndromes [5] [2]. |

| TET Family | Active demethylation (5mC → 5hmC → 5fC → 5caC) | 5hmC highly enriched in neurons; dysregulation implicated in Rett syndrome and other NDDs [6] [2]. |

| MECP2 | Reads DNA methylation and recruits repressive complexes | Loss-of-function mutations are the primary cause of Rett Syndrome [6] [3]. |

DNA Methylation in Neurodevelopmental Disorders

DNA methylation is a key biomarker and mechanistic player in NDDs. Genome-wide epigenetic signatures, known as EpiSign, can help classify and diagnose over 50 different syndromic forms of intellectual and developmental disability (IDD) [3]. For instance, in Rett syndrome, caused by mutations in MECP2, the inability to read methylated DNA leads to widespread transcriptional dysregulation in the brain [6] [3]. Furthermore, studies of newborn blood spots have identified differential methylation regions (DMRs) associated with a later diagnosis of ASD, suggesting that perinatal epigenetic markers could serve as predictive biomarkers for disease risk [3]. Environmental factors during critical developmental windows can also induce lasting changes to the DNA methylome, potentially increasing susceptibility to NDDs [1] [4].

Histone Modifications

The Histone Code and Major Modification Types

Histones are the core protein components of nucleosomes, around which DNA is wrapped. Their N-terminal tails are subject to a wide array of post-translational modifications (PTMs), including acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitylation [8] [9]. The "histone code" hypothesis posits that these modifications, alone or in combination, dictate chromatin structure and gene expression by recruiting effector proteins ("readers") [8] [9]. These marks are dynamically added by "writer" enzymes and removed by "eraser" enzymes [8] [2].

Table 2: Major Histone Modifications and Their Functions

| Modification | General Function | Associated Enzymes |

|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 | Transcriptional activation (promoters) | Writers: MLL/COMPASS families; Erasers: KDM5 family [8]. |

| H3K27ac | Transcriptional activation (enhancers/promoters) | Writers: p300/CBP; Erasers: HDAC1-3 [8]. |

| H3K36me3 | Transcriptional activation (gene bodies) | Writers: SETD2; Erasers: KDM2/4 families [8] [7]. |

| H3K9me3 | Transcriptional repression, heterochromatin formation | Writers: SUV39H1/2; Erasers: KDM4 family [8] [9]. |

| H3K27me3 | Transcriptional repression, facultative heterochromatin | Writers: EZH2 (PRC2); Erasers: KDM6 family (e.g., UTX) [8] [9]. |

| H3S10p | Chromosome condensation during mitosis | Writers: Aurora B kinase [8]. |

| γH2A.X (H2AXS139p) | Marker for DNA double-strand breaks | Writers: ATM/ATR kinases [8] [1]. |

Experimental Analysis of Histone Modifications

The primary method for mapping histone modifications is chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP). This technique uses specific antibodies to isolate a protein or modification of interest, along with its bound DNA. The co-precipitated DNA is then sequenced (ChIP-seq) and mapped to the genome to identify the location and abundance of the mark [8]. Recent technological advances have enabled profiling at the single-cell level with methods like scCUT&TAG and scChIC, which use antibody-tethered enzymes (Tn5 transposase or MNase) to tag or cleave DNA associated with specific histone marks [7].

Histone Modifications in Neural Development and Disease

Histone modifications are integral to neuronal fate specification, differentiation, and function. For example, the repressive mark H3K27me3, deposited by the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2), temporally regulates developmental genes in embryonic stem cells, including Hox and Sox genes, and its dysregulation is linked to NDDs [8] [4]. During myoblast differentiation, a process analogous to neurogenesis, the loss of repressive marks like H3K9me and H3K27me and the gain of activating marks like H3K4me are required for the expression of key differentiation genes [10]. Mutations in histone-modifying enzymes are directly causative of NDDs classified as "chromatinopathies." For instance, haploinsufficiency of EZH2, the H3K27me3 methyltransferase, is associated with Weaver syndrome, which features intellectual disability and overgrowth [3].

Diagram 1: Histone modification dynamics. Writer and eraser enzymes add or remove histone marks, which are then recognized by reader proteins that direct the functional outcome of open or closed chromatin states.

Chromatin Remodeling

Mechanisms of ATP-Dependent Remodeling

Chromatin remodeling refers to the dynamic alteration of chromatin structure to regulate DNA accessibility. This is primarily achieved by two classes of protein complexes: 1) covalent histone-modifying complexes (discussed in Section 3) and 2) ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes [9]. These multi-subunit complexes use the energy from ATP hydrolysis to slide nucleosomes along DNA, evict histones, or exchange standard histones for histone variants, thereby making genomic regions more or less accessible to the transcriptional machinery [9].

The major families of remodeling complexes in eukaryotes are:

- SWI/SNF: Functions in nucleosome sliding and eviction; involved in gene activation and DNA repair [9].

- ISWI: Primarily involved in nucleosome spacing and chromatin assembly after DNA replication [9].

- NuRD/Mi-2/CHD: Often associated with transcriptional repression and is crucial for embryonic stem cell pluripotency [9].

- INO80: Participates in DNA double-strand break repair and nucleotide-excision repair [9].

Chromatin Remodeling in DNA Damage and Development

Chromatin remodeling is a critical early response to DNA damage. Within seconds of a double-strand break, PARP1 is activated and recruits the chromatin remodeler Alc1, leading to rapid local chromatin relaxation [9]. This is followed by phosphorylation of the histone variant H2AX to form γH2AX, which spreads over a large domain and recruits DNA repair proteins like MDC1 and RNF8, the latter mediating further decondensation through the NuRD complex [1] [9].

During development, these complexes are essential for maintaining the balance between stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. For example, the NuRD complex represses genes that promote differentiation, thereby maintaining pluripotency in embryonic stem cells [1] [9]. In the developing cortex, precise control of chromatin accessibility is required for the sequential expression of transcription factors that guide neuronal fate. Mutations in genes encoding subunits of these complexes, such as CHD7 and CHD8, are strongly linked to syndromes featuring intellectual disability and autism [4].

Integrated Methodologies and the Research Toolkit

The most recent advances in epigenetics involve multi-omics approaches that simultaneously profile multiple layers of epigenetic information in the same single cell. Single-cell Epi2-seq (scEpi2-seq) is a cutting-edge technique that provides a joint readout of histone modifications and DNA methylation [7]. The workflow involves:

- Cell Permeabilization and Antibody Binding: Single cells are permeabilized, and a proteinA-MNase fusion protein is tethered to specific histone modifications using antibodies.

- MNase Digestion: Addition of Ca²⁺ initiates MNase digestion, cleaving DNA around the targeted nucleosomes.

- Library Preparation and Barcoding: Fragments are repaired, A-tailed, and ligated to adaptors containing a single-cell barcode and UMI.

- TAPS Conversion: The pooled material undergoes TET-assisted pyridine borane sequencing (TAPS), which converts methylated cytosine to uracil without damaging the adaptor sequences.

- Sequencing and Analysis: After sequencing, reads are demultiplexed to reveal both the genomic location of histone modifications (from read mapping) and the DNA methylation status (from C-to-T conversions) in each individual cell [7].

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit - Key Reagents for Epigenetic Profiling

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Protein A-MNase Fusion Protein | Enzyme tethered by antibodies to cleave DNA at specific histone modifications. | Core component of scChIC and scEpi2-seq for mapping histone marks [7]. |

| Tn5 Transposase | Enzyme that simultaneously fragments DNA and adds sequencing adaptors. | Used in scCUT&TAG for profiling histone modifications and open chromatin [7]. |

| Bisulfite Reagent | Chemical that deaminates unmethylated cytosine to uracil. | Critical for bisulfite sequencing-based DNA methylation analysis (e.g., scBS-seq) [7]. |

| TET Enzyme | Enzyme that oxidizes 5mC to 5hmC and beyond. | Key component of TAPS for gentle, bisulfite-free methylation detection [7]. |

| HDAC / HAT Inhibitors | Small molecules that inhibit histone deacetylases or acetyltransferases. | Used to test the functional role of histone acetylation in gene expression [2]. |

| EpiSign Classifier | A machine learning classifier trained on DNA methylation array data. | Used in clinical genetics to diagnose syndromic IDDs from blood DNA [3]. |

Diagram 2: scEpi2-seq workflow for simultaneous profiling of histone modifications and DNA methylation in single cells.

The intricate interplay between DNA methylation, histone modifications, and chromatin remodeling forms a sophisticated regulatory network that governs gene expression during brain development. Disruption of any of these mechanisms can lead to a failure to establish proper neuronal identity, connectivity, and function, ultimately contributing to the etiology of NDDs. The ongoing development of advanced single-cell and multi-omics technologies, such as scEpi2-seq, is providing an unprecedented view of the dynamics and interactions within the epigenome. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these core mechanisms is fundamental. The continued mining of epigenetic data, especially from accessible human tissues, holds immense promise for developing novel diagnostic biomarkers, uncovering convergent pathological pathways, and identifying new therapeutic targets for neurodevelopmental disorders.

The development of the cerebral cortex is a remarkably complex process orchestrated by precise spatiotemporal gene expression programs. Emerging research elucidates how epigenetic mechanisms—including histone modifications, DNA methylation, chromatin remodeling, and RNA modifications—serve as master conductors of neural progenitor fate decisions, neuronal migration, and circuit formation. This technical review synthesizes current understanding of these regulatory processes and their critical roles in corticogenesis. Furthermore, we examine how disruptions to these epigenetic pathways contribute to neurodevelopmental disorders, providing a mechanistic foundation for therapeutic development. The integration of recent advances in sequencing technologies and mechanistic studies offers unprecedented opportunities for identifying novel targets and developing targeted interventions for neurodevelopmental pathology.

Corticogenesis involves the highly orchestrated transformation of a homogeneous neuroepithelial sheet into the complex, layered structure of the cerebral cortex. This process generates a remarkable diversity of neural cell types from a heterogeneous pool of progenitors with distinct spatial and temporal identities [11]. The embryonic cerebral cortex arises initially from neuroepithelial cells (NECs) that expand during neural tube closure. These NECs give rise to radial glial cells (RGCs), which serve as the primary neural progenitors throughout cortical neurogenesis [11]. RGCs undergo progressive transitions through temporal competence states, sequentially producing different neuronal subtypes and glia [11] [12].

The cerebral cortex develops in an inside-out manner, with early-born neurons forming deep layers and later-born neurons migrating past them to settle in superficial layers [11]. Early in neurogenesis, RGCs undergo direct neurogenesis, asymmetrically dividing to generate deep-layer neurons. During mid-neurogenesis, RGC competence transitions to indirect neurogenesis, producing upper-layer neurons via intermediate progenitor (IP) cells [11] [12]. As corticogenesis progresses, RGCs eventually shift to gliogenesis, producing astrocytes and oligodendrocytes [11]. Proper execution of these developmental sequences requires precise spatial and temporal regulation of stage-specific transcriptional programs, coordinated largely by epigenetic mechanisms.

Epigenetic Mechanisms in Cortical Development

Histone Modifications

Chromatin structure consists of DNA wrapped around histone octamers (two copies each of H2A, H2B, H3, and H4), forming nucleosomes. The N-terminal tails of histone proteins undergo post-translational modifications including methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and sumoylation at specific residues [11]. These modifications regulate DNA accessibility and gene expression by altering chromatin structure and recruiting transcriptional complexes.

Table 1: Key Histone Modifications in Corticogenesis

| Modification | Associated Function | Catalytic Enzymes | Effect on Transcription | Role in Corticogenesis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3K27me3 | Polycomb-mediated repression | Ezh2 | Repressive | Dynamically regulates RGC competence transitions; deletion affects neurogenesis timing [11] |

| H3K4me3 | Promoter-associated | SET1/MLL complexes | Active | Marks active promoters; found in bivalent domains with H3K27me3 [11] |

| H3K9me3 | Heterochromatin formation | Setdb1 | Repressive | Regulates deep vs. upper layer neuron production; affects gliogenesis timing [11] |

| H3K27ac | Enhancer activation | Cbp/p300 | Active | Marks active enhancers; dynamic during neuronal differentiation [11] |

H3K27me3, mediated by Ezh2 and the Polycomb repressive complex, shows dynamic distribution during corticogenesis [11]. In NECs, H3K27me3 frequently co-occurs with H3K4me3 at "bivalent" promoters—genes poised for activation during differentiation [11]. Temporal changes in H3K27me3 patterning help transition RGCs through developmental competence states. Ezh2 deletion studies demonstrate its critical role in timing neurogenesis and gliogenesis [11]. Deletion before neurogenesis onset accelerates neural lineage progression, while deletion during neurogenesis prolongs neurogenesis and delays astrogliogenesis [11].

H3K9me3 represents another repressive histone modification important for cell fate specification. Setdb1 deletion, which catalyzes H3K9me3, increases upper-layer neuron production at the expense of deep-layer neurons and causes premature astrogliogenesis [11]. Conversely, H3K27ac marks active enhancers and promoters. Cbp (a histone acetyltransferase) knockdown reduces late-born upper-layer neurons and impairs the transition to gliogenesis [11]. Prdm16 temporally regulates enhancer states in RGCs by modulating H3K27ac, instructing neuronal fate specification [11].

DNA Methylation

DNA methylation involves covalent addition of methyl groups to cytosine nucleotides, primarily at CpG dinucleotides (with notable non-CpG methylation in neurons). This modification is fundamental to development, influencing DNA-protein interactions and generally conferring transcriptional repression [11] [13]. DNA methyltransferases Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b establish de novo methylation, while Dnmt1 maintains methylation patterns during cell division [11] [13]. Active demethylation occurs through ten-eleven translocation (TET) enzymes that oxidize 5-methylcytosine (5mC) to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) and further derivatives [13].

Table 2: DNA Methylation Machinery in Cortical Development

| Component | Type | Function | Role in Corticogenesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNMT1 | Maintenance methyltransferase | Preferentially methylates hemi-methylated DNA | Maintains methylation patterns during RGC division [13] |

| DNMT3A/B | De novo methyltransferases | Adds methyl groups to unmethylated cytosines | Establishes new methylation patterns during fate transitions [11] |

| TET enzymes | Demethylases | Oxidizes 5mC to 5hmC and beyond | Facilitates active DNA demethylation in response to developmental cues [13] |

| UHRF1 | Reader/Effector | Recognizes H3K9me3 and recruits DNMT1 | Links histone methylation to DNA methylation maintenance [11] |

| MECP2 | Methyl-CpG binding protein | Binds methylated DNA and recruits repressive complexes | Mutated in Rett syndrome; regulates activity-dependent neuronal genes [14] [13] |

RGCs undergo successive waves of DNA demethylation and remethylation during corticogenesis [11]. Early demethylation activates neurogenic genes, while later demethylation facilitates gliogenic gene expression. Finally, glial cells undergo extensive de novo methylation at neuronal identity genes to solidify glial fate [11]. DNA methylation patterns are established through interplay with histone modifications. For example, UHRF1 recognizes H3K9me3 and recruits DNMT1, linking repressive histone marking to DNA methylation maintenance [11].

Chromatin Remodeling Complexes

ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes regulate gene accessibility by sliding, evicting, or restructuring nucleosomes. The BAF (SWI/SNF) and NuRD complexes exhibit particularly important roles in corticogenesis [11].

The BAF complex undergoes subunit composition changes during neural development. RGCs express a specific complex containing BAF45a, BAF53a, and BAF55a, which maintains progenitor status and regulates neurogenic-gliogenic transitions [11]. Upon neuronal differentiation, these subunits are replaced by BAF45b/c, BAF53b, and BAF55b [11]. BAF subunit deletion (BAF45a/53a) impairs RGC proliferation, while complete BAF complex disruption causes a global shift from active to repressive histone modifications, particularly increasing H3K27me3 at neuronal differentiation genes [11].

The NuRD complex contains histone deacetylase (HDAC1/2) activity and nucleosome remodeling capability. Core members include methyl-CpG-binding domain proteins (Mbd1/2/3) that recruit the complex to methylated DNA regions, facilitating gene silencing [11].

Non-Coding RNAs and RNA Modifications

Non-coding RNAs, including microRNAs (miRNAs) and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), post-transcriptionally regulate gene expression. Single-cell analysis reveals cell-type-specific lncRNA expression in the developing human neocortex [12]. Functional studies demonstrate that specific lncRNAs regulate cortical development; for example, lncRNA Pnky knockdown increases neuronal differentiation from postnatal neural stem cells [12].

RNA modifications represent another layer of epigenetic regulation. N6-Methyladenosine (m6A)—the most abundant mRNA modification—regulates translation and decay rates. The METTL3-containing methyltransferase complex catalyzes m6A addition. Mettl3 knockdown in mouse ESCs impairs differentiation and increases neural progenitor proliferation [12]. m6A also regulates neurogenesis by modulating the histone methyltransferase Ezh2, illustrating cross-talk between RNA and histone modifications [12].

Figure 1: Epigenetic Regulation of Corticogenesis. Multiple epigenetic mechanisms coordinate the transition of neuroepithelial cells (NECs) to radial glia (RGCs) and their subsequent production of diverse cortical cell types in a spatiotemporally precise manner.

Experimental Approaches for Epigenetic Analysis in Corticogenesis

Genome-Wide Methylation Analysis

The Infinium Human Methylation BeadChip platform (850K) enables genome-wide DNA methylation analysis [15]. This methodology involves:

DNA Extraction and Bisulfite Conversion: Genomic DNA is treated with bisulfite using the EZ DNA Methylation Kit, converting unmethylated cytosines to uracils while leaving methylated cytosines unchanged.

Array Hybridization: Bisulfite-converted DNA is hybridized to the BeadChip following Illumina Infinium HD Methylation protocols.

Data Processing: Raw intensity data (IDAT files) are processed using bioinformatic packages like ChAMP in R, with annotation to reference genomes (e.g., hg19).

Quality Control: Probes with detection p-values >0.01, located on sex chromosomes, related to SNPs, or multi-hit probes are excluded.

Normalization: Beta-mixture quantile dilation (BMIQ) algorithm corrects for probe-type bias.

DNA methylation levels are represented as β-values (0=unmethylated, 1=fully methylated). Differential methylation analysis identifies regions associated with specific developmental stages or experimental conditions [15].

MethylTarget Sequencing for Targeted Validation

MethylTarget sequencing provides high-throughput validation of specific CpG sites:

Primer Design: Target-specific probes and primers are designed for regions of interest.

Multiplex PCR Optimization: Single-site PCR conditions are optimized, then primers are combined into multiplex panels.

Library Preparation: After bisulfite conversion, multiplex PCR amplifies target sites. Indexed primers add Illumina-compatible tags.

Sequencing: Libraries undergo size verification (Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer) and sequencing on Illumina platforms.

This targeted approach validates differentially methylated regions identified through genome-wide screens with higher coverage and lower cost than whole-genome bisulfite sequencing [15].

Single-Cell and Single-Nuclei Epigenomic Technologies

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and single-nuclei Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin sequencing (snATAC-seq) enable cell-type-specific resolution of transcriptional and epigenetic states [14]. These methodologies:

- Resolve cellular heterogeneity in developing cortex

- Identify cell-type-specific regulatory elements

- Reveal temporal progression of epigenetic states during lineage commitment

Spatial transcriptomics methodologies further contextualize these findings by providing geographical information about gene expression patterns within tissue architecture [14].

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Epigenetic Analysis. Comprehensive epigenetic investigation combines multiple high-throughput technologies with targeted validation approaches to elucidate mechanisms of cortical development.

Epigenetics in Neurodevelopmental Disorders

Mechanistic Insights from Disease Associations

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and whole-exome/genome sequencing have identified numerous epigenetic regulators associated with neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs) [14]. For example, mutations in MECP2 cause Rett syndrome, linking DNA methylation interpretation to neuronal dysfunction [14] [13]. Similarly, mutations in genes encoding chromatin modifiers (EHMT1, KMT2A, KDM5C) and BAF complex subunits occur across autism spectrum disorder (ASD), intellectual disability, and schizophrenia [14].

These genetic findings illuminate mechanistic pathways in corticogenesis. Mutations often affect regulators of histone modifications (writers, erasers, readers) or chromatin remodeling complexes, disrupting precise temporal control of gene expression during brain development [14]. The resulting imbalances in neuronal production, migration, or differentiation manifest as neurodevelopmental pathology.

Environmental Interactions and Early-Life Stress

The epigenome mediates gene-environment interactions during development. Early-life stress (ELS) induces persistent epigenetic changes that alter stress response systems and increase NDD risk [13]. ELS associates with lasting DNA methylation changes at genes regulating glucocorticoid signaling (NR3C1), neural plasticity, and epigenetic machinery itself [13]. These changes can accelerate epigenetic aging—a biomarker of biological vs. chronological age discrepancy [13].

Environmental exposures during sensitive periods of brain development can cause long-lasting epigenetic modifications that influence neurodevelopmental trajectories [15]. For instance, prenatal exposure to air pollutants associates with differential methylation of neurodevelopmental genes and subsequent effects on cognitive and motor function [15].

Table 3: Epigenetic Changes in Neurodevelopmental Disorders

| Disorder | Epigenetic Alterations | Functional Consequences | Research Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rett Syndrome | MECP2 mutations impair methyl-DNA reading | Disrupted neuronal maturation and synaptic function | Patient mutations, mouse models [14] [13] |

| Autism Spectrum Disorder | Mutations in chromatin modifiers (KMT2A, KDM5C) and BAF complex | Altered cortical connectivity and excitation/inhibition balance | GWAS and sequencing studies [14] |

| Developmental Coordination Disorder | DNA methylation changes at FAM45A, FAM184A, SEZ6, GPD2 | Impaired motor coordination and function | Methylation array analysis [15] |

| Early-Life Stress Disorders | DNA methylation changes at NR3C1, BDNF, SLC6A4 | Hyperactive stress response, altered emotional regulation | Human cohort studies, animal models [13] |

Research Toolkit: Reagents and Methodologies

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Epigenetic Studies in Corticogenesis

| Category | Specific Reagents/Tools | Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methylation Analysis | Infinium Methylation 850K BeadChip | Genome-wide methylation screening | Covers >850,000 CpG sites; requires bisulfite conversion [15] |

| EZ DNA Methylation Kit | Bisulfite conversion | Conversion efficiency critical for data quality [15] | |

| MethylTarget sequencing | Targeted validation | High coverage for specific genomic regions [15] | |

| Chromatin Analysis | scATAC-seq kits | Single-cell chromatin accessibility | Requires fresh nuclei or cryopreserved samples [14] |

| ChIP-grade antibodies | Histone modification mapping | Antibody specificity validation essential [11] | |

| Transcriptomics | scRNA-seq kits | Single-cell transcriptomics | Cell dissociation optimization critical for viability [14] |

| Bioinformatic Tools | ChAMP package | Methylation data analysis | Includes normalization, DMP/DMR identification [15] |

| Seurat/Signac | Single-cell multi-omics integration | Enables correlation of epigenetic and transcriptional states [14] | |

| Experimental Models | Cerebral organoids | Human corticogenesis modeling | Recapitulates some aspects of human cortical development [12] |

| Conditional knockout mice | Cell-type-specific gene function | Enables temporal control of gene deletion [11] |

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

Epigenetic mechanisms represent promising therapeutic targets for neurodevelopmental disorders due to their dynamic nature and responsiveness to pharmacological manipulation. Several strategic approaches show particular promise:

Small Molecule Inhibitors: Compounds targeting epigenetic enzymes (HDAC inhibitors, EZH2 inhibitors, BET bromodomain inhibitors) are under investigation for various neurological conditions [14]. These compounds can potentially reverse aberrant epigenetic states associated with disease.

Targeted Epigenome Editing: CRISPR-based systems fused to epigenetic effector domains enable precise manipulation of epigenetic states at specific genomic loci [14]. This approach offers potential for correcting disease-associated epigenetic dysregulation without altering DNA sequence.

Biomarker Development: Epigenetic signatures in accessible tissues (blood) may serve as biomarkers for early detection, monitoring, and personalized treatment of neurodevelopmental disorders [15].

Future research directions should focus on:

- Elucidating cell-type-specific epigenetic dynamics throughout human corticogenesis

- Understanding cross-talk between different epigenetic modifications

- Developing more specific epigenetic modulators with reduced off-target effects

- Integrating multi-omic datasets to build predictive models of neurodevelopment

The continued advancement of neuroepigenetics will not only deepen our understanding of normal brain development but also catalyze novel therapeutic strategies for neurodevelopmental disorders.

The term epigenetics refers to persistent changes in transcriptional state or potential that do not involve alterations to the underlying DNA sequence, regulated by molecular mechanisms including DNA methylation, post-translational histone modifications (PTHMs), and non-coding RNAs [13]. These mechanisms are particularly critical during brain development, where they choreograph complex gene programs through precise spatiotemporal control of gene expression [13]. The epigenetic machinery consists of "writer" enzymes that add chemical marks, "eraser" enzymes that remove them, and "reader" proteins that interpret these marks and recruit effector complexes [16]. When mutations disrupt these specialized components, they can cause severe neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs) with lifelong consequences [4]. This technical review examines the molecular pathology, clinical manifestations, and research methodologies for congenital disorders arising from mutations in key epigenetic regulator genes, with a specific focus on their role in neurodevelopmental processes.

The developing brain is exceptionally vulnerable to disruptions in epigenetic regulation. Proper formation of the mammalian neocortex relies on tightly controlled processes including progenitor proliferation, neuronal differentiation, migration, and circuit formation [4]. These processes require precise temporal and spatial coordination of gene expression programs, which epigenetic mechanisms help orchestrate. Deficits in neuronal identity, proportion, or function that underlie many NDDs can be provoked by genetic mutations in epigenetic regulator genes, leading to malformations of cortical development (MCDs) [4]. This review focuses specifically on mutations in the epigenetic machinery itself, examining how these defects disrupt normal neurodevelopment and lead to recognizable genetic syndromes.

Core Epigenetic Machinery and Associated Disorders

Methyl-CpG Binding Protein 2 (MeCP2) and Rett Syndrome

Methyl CpG binding protein 2 (MeCP2) functions as a crucial reader of DNA methylation marks and is primarily implicated in Rett syndrome (RTT), a severe neurodevelopmental disorder [16]. MeCP2 contains several functional domains including a methyl-binding domain (MBD), a transcriptional repression domain (TRD), and a nuclear localization signal (NLS) [16]. The protein serves as a methylation-dependent transcriptional modulator within chromatin, capable of both repressive and activating functions through interactions with different cofactors [16].

Rett syndrome typically affects girls and is characterized by a period of apparently normal development for 6-18 months followed by developmental regression with loss of motor and communicative skills [16]. Most RTT cases (over 99%) result from de novo mutations in the X-linked MECP2 gene, with the majority being C>T transitions at CpG hotspots that likely reflect abnormal methylation in the male germline [16]. These mutations are almost exclusively of paternal origin, which may be explained by elevated methylation levels and mitotic divisions in the male germline [16].

From a structural perspective, MeCP2 mutations in RTT can be categorized into three main groups affecting different protein domains: (1) mutations affecting the N-terminal domain (NTD), which modulates DNA interaction and protein turnover; (2) mutations affecting the MBD, which disrupt DNA binding affinity and stability; and (3) mutations affecting other regions of the protein [16]. The MBD represents the only structurally ordered portion of MeCP2, and mutations within this domain significantly impact tertiary structure folding and function [16].

Beyond its role in transcription, MeCP2 also regulates mRNA splicing through interactions with splicing factors and epigenetic modifications [17]. Mass spectrometry analyses have revealed that the majority of MeCP2-associated proteins are involved in RNA splicing, and MeCP2 knockdown in cortical neurons leads to widespread alterations in alternative splicing [17]. This splicing regulation involves specific epigenetic signatures, with 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) and H3K4me3 enriched in down-regulated exons, while H3K36me3 is enriched in up-regulated exons [17].

Table 1: MeCP2 Protein Domains and RTT-Associated Mutations

| Domain | Amino Acid Range (E2 isoform) | Primary Function | Consequence of Mutation |

|---|---|---|---|

| N-terminal Domain (NTD) | 1-78 | Modulates DNA binding via MBD; influences protein turnover | Altered DNA binding stability and protein degradation rates |

| Methyl-Binding Domain (MBD) | 79-162 | Recognizes and binds methylated CpG dinucleotides | Reduced DNA binding affinity; disrupted protein folding |

| Intervening Domain (ID) | 163-207 | Connects MBD and TRD; function not fully characterized | Variable clinical presentations |

| Transcriptional Repression Domain (TRD) | 208-310 | Interacts with co-repressor complexes (e.g., NCoR/SMRT, Sin3a/HDAC) | Loss of transcriptional repression capability |

| Nuclear Localization Signal (NLS) | 253-271 | Directs protein to nucleus | Impaired nuclear localization |

| C-terminal Domain (CTD) | 311-486 | Contributes to chromatin binding; role in protein-protein interactions | Disrupted chromatin interactions |

DNMT3A and Overgrowth Syndrome

The DNMT3A gene encodes a DNA methyltransferase 3 alpha enzyme essential for establishing DNA methylation patterns during embryonic development [18]. This enzyme functions as a writer that adds methyl groups to cytosine bases, particularly during pre-natal development when methylation patterns are established [18]. DNMT3A contains three critical functional domains: a PWWP domain involved in protein-protein interactions and chromatin targeting, an ADD domain that mediates histone binding, and a C-terminal DNA methyltransferase domain that catalyzes methylation [19].

Mutations in DNMT3A cause DNMT3A overgrowth syndrome (also known as Tatton-Brown-Rahman syndrome), characterized by taller than average height (overgrowth), a distinctive facial appearance, and intellectual disability [19] [18]. The facial gestalt typically includes a round face, heavy horizontal eyebrows, and narrow palpebral fissures [19]. Height is significantly increased, ranging from 1.8 to 4.2 standard deviations above the mean, while head circumference also shows increases from 1.2 to 5.1 standard deviations above the mean [19]. Intellectual disability is a consistent feature, described as moderate in most cases and mild in others [19].

The mutations identified in DNMT3A overgrowth syndrome are scattered throughout the functional domains of the protein and include missense mutations, small frameshifting insertions, and in-frame deletions [19]. Protein structure modeling suggests these mutations interfere with domain-domain interactions and histone binding, thereby disrupting de novo methylation patterns during development [19]. Unlike the somatic mutations in DNMT3A found in hematological malignancies (which frequently affect Arg882), the germline mutations in overgrowth syndrome show different mutational spectra and likely distinct pathogenic mechanisms [19].

Table 2: DNMT3A Overgrowth Syndrome Clinical Features and Associated Mutations

| Mutation Type | Protein Alteration | Height (SD above mean) | Head Circumference (SD above mean) | Intellectual Disability | Additional Clinical Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-frame deletion | p.Trp297del | 2.6 | 2.2 | Moderate | Seizures |

| Nonsynonymous | p.Leu648Pro | 3.4 | 5.1 | Mild | Mild hemihypertrophy, umbilical hernia |

| Nonsynonymous | p.Arg749Cys | 4.0 | 3.8 | Moderate | Vesico-ureteric reflux, patella subluxation |

| Frameshift | p.Arg767fs | 3.8 | 1.6 | Moderate | - |

| Nonsynonymous | p.Pro904Leu | 3.7 | 1.2 | Moderate | - |

MBD Family Proteins and Neurological Disorders

The methyl-CpG binding domain (MBD) family of proteins serves as critical readers of DNA methylation, recruiting chromatin remodelers, histone deacetylases, and methylases to methylated DNA associated with gene repression [20]. This family includes MBD1, MBD2, MBD3, MBD4, and MeCP2 [20]. While these proteins share the ability to recognize methylated DNA, they have distinct functions and binding specificities.

MBD3 protein deserves special attention as it does not selectively recognize methyl-CpG islands but can bind to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine and unmethylated DNA [21]. Recent research has implicated MBD3 in epileptogenesis, with studies showing that seizures induced by pentylenetetrazole (PTZ) cause transient, brain area-specific increases in Mbd3 protein levels in the entorhinal cortex and amygdala [21]. Overexpression of Mbd3 in the amygdala using AAV vectors decreased anxiety, increased excitability in open-field tests, and accelerated epileptogenesis in the PTZ-kindling model [21].

At the molecular level, Mbd3 overexpression influences genes associated with the Wnt and Notch pathways, potassium channel function, and GABAB receptor signaling [21]. This suggests that increased Mbd3 expression has pro-epileptic properties and contributes to regulating multiple pathways involved in seizure development. Importantly, seizures themselves transiently elevate Mbd3 levels, potentially creating a vicious circle that aggravates disease progression [21].

Table 3: MBD Family Proteins and Their Roles in Neurological Function

| Protein | Methylation Binding Specificity | Primary Functions | Associated Neurological Deficits |

|---|---|---|---|

| MeCP2 | Methylated CpG, 5hmC | Transcriptional modulation; mRNA splicing regulation | Rett syndrome; autism-like features; intellectual disability |

| MBD1 | Methylated CpG | Transcriptional repression; maintenance of heterochromatin | Impaired neurogenesis; cognitive deficits (animal models) |

| MBD2 | Methylated CpG | Transcriptional repression; NuRD complex component | Limited neurological associations |

| MBD3 | Unmethylated DNA; 5hmC | NuRD complex component; transcriptional regulation | Epileptogenesis; anxiety-like behaviors |

| MBD4 | Methylated CpG | DNA repair; glycosylase activity | Not primarily associated with neurological disorders |

Molecular Mechanisms and Pathophysiology

Disrupted DNA Methylation Signaling

The molecular pathophysiology of epigenetic regulator disorders centers on disrupted interpretation and establishment of DNA methylation patterns. MeCP2 functions as a key interpreter of DNA methylation marks in the brain, with mutations leading to widespread downstream effects on gene expression. MeCP2 can regulate gene expression bidirectionally—it can repress transcription by recruiting co-repressor complexes like HDAC-mSin3A and NCoR-SMRT, while also activating transcription through interaction with CREB1 [17]. This dual functionality explains why Mecp2-null mice show both up- and down-regulation of different genes [17].

DNMT3A mutations disrupt the establishment of DNA methylation patterns during development. Protein structure modeling indicates that residues targeted by nonsynonymous mutations in the methyltransferase domain are located at the interaction interface with the ADD domain, while those in the ADD domain are close to the histone H3 binding region [19]. This positioning suggests that overgrowth syndrome mutations interfere with domain-domain interactions and histone binding, thereby disrupting de novo methylation [19]. The resultant reduction in DNA methylation likely dysregulates important developmental genes, though the precise mechanisms linking these changes to specific clinical features of overgrowth syndrome require further elucidation.

Chromatin Remodeling and Transcriptional Dysregulation

Beyond DNA methylation, mutations in epigenetic regulators cause broad alterations in chromatin architecture and accessibility. MeCP2 interacts with multiple chromatin remodeling complexes and helps maintain chromatin architecture in neurons [16]. The protein exhibits characteristics of an intrinsically disordered protein (IDP) with relatively low contents of secondary and tertiary structure organization in solution, yet it contains well-defined structural/functional domains that mediate specific interactions [16].

The relationship between MeCP2 and histone modifications represents another important pathogenic mechanism. MeCP2-regulated exons display specific epigenetic signatures, with enrichment of 5hmC and H3K4me3 in down-regulated exons, while H3K36me3 signatures are enriched in up-regulated exons following Mecp2 knockdown [17]. This demonstrates how DNA methylation readers interact with histone modifications to regulate alternative splicing and gene expression in the nervous system.

Diagram 1: Molecular Pathways from Epigenetic Mutations to Neurodevelopmental Defects. This diagram illustrates how mutations in different epigenetic regulators converge on transcriptional dysregulation through distinct but interconnected molecular pathways.

Splicing Regulation and Non-Coding RNA Involvement

An emerging mechanism in epigenetic disorders involves disrupted regulation of mRNA splicing and non-coding RNA processing. MeCP2 regulates alternative splicing through interactions with splicing factors and epigenetic modifications at regulated exons [17]. RNA sequencing analysis of Mecp2-knockdown neurons revealed 1225 exons up-regulated and 608 exons down-regulated, with genes containing these exons primarily involved in synaptic functions and mRNA splicing itself [17]. This creates a feed-forward loop where disrupted splicing machinery amplifies the initial molecular defect.

Non-coding RNAs, including microRNAs (miRNAs) and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), represent another layer of epigenetic regulation that becomes disrupted in these disorders. MeCP2 interacts with the Drosha/DGCR8 complex to modulate microRNA processing [16] [17]. Specific miRNAs such as miR-124 and miR-9 are involved in neuronal lineage specification, and disruptions in their expression can lead to disordered neuroarchitecture [22]. Altered expression of miRNAs including miR-137 and miR-132 has been found in children with autism spectrum disorders, linking them to deficits in synaptic function and plasticity [22].

Research Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Animal Model Development and Validation

Research into epigenetic disorders relies heavily on genetically engineered animal models that recapitulate human mutations:

Mecp2-Null Rat Model Generation:

- Methodology: TALEN-based gene targeting technology creates precise 10bp deletions in the Mecp2 gene [17].

- Validation: PCR and Sanger sequencing confirm gene disruption; Western blot analysis using protein lysates from Mecp2-null (KO) and wild-type (WT) littermate rats verify MeCP2 protein depletion [17].

- Application: Used for mass spectrometry analysis of MeCP2-associated proteins and studying RTT pathophysiology in a mammalian model system.

AAV-Mediated Mbd3 Overexpression in Rat Amygdala:

- Viral Vector: AAV-SYN-Mbd3-GFP with synapsin promoter for neuronal-specific expression [21].

- Stereotactic Injection: Bilateral injections into basolateral amygdala (BLA) with coordinates: AP: -2.8; L: ±4.7; DV: -7.2 [21].

- Injection Parameters: 0.4 μl per hemisphere at rate of 0.2 μl per minute [21].

- Functional Assessment: Behavioral tests including open-field assessment, anxiety measures, and PTZ kindling for seizure susceptibility [21].

Proteomic and Transcriptomic Analyses

Mass spectrometry-based identification of MeCP2-associated proteins:

- Sample Preparation: Cortical lysates from Mecp2-null and WT littermate rats [17].

- Affinity Purification: Utilization of endogenous tandem Histidine residues (a.a. 366-372) in MeCP2 with Ni-NTA resin [17].

- Control Strategy: Candidate proteins identified in WT but not KO lysates considered bona fide MeCP2-associated proteins [17].

- Additional Validation: Complementary approaches in 293T cells expressing His-MeCP2 and immunoprecipitation with anti-MeCP2 antibody in mouse cortical neurons [17].

- Bioinformatic Analysis: GO enrichment analysis and protein-protein interaction network mapping using identified binding partners [17].

RNA sequencing for alternative splicing analysis:

- Cell Culture: Mouse cortical neurons cultured in vitro [17].

- MeCP2 Knockdown: Lentivirus expressing shRNA targeting mouse Mecp2 infected at DIV2 [17].

- Validation: Knockdown efficiency confirmed by real-time PCR and Western blot [17].

- Sequencing and Analysis: RNA deep sequencing with DEXseq software package for exon usage differences [17].

- Epigenetic Integration: ChIP-seq data analysis for MeCP2 binding, Pol II distribution, and epigenetic markers (5mC, 5hmC, H3K4me3, H3K36me3) in regulated exons [17].

Electrophysiological and Behavioral Assessments

PTZ (pentylenetetrazole) seizure threshold and kindling monitoring:

- EEG Electrode Implantation: Surface electrodes stereotactically implanted over frontal cortex (AP: 3.0; L: +2.0 mm from Bregma) with reference and ground electrodes over cerebellum [21].

- PTZ Administration: Subconvulsive doses (30-40 mg/kg) administered periodically to induce kindling [21].

- Seizure Monitoring: Continuous EEG recording with Racine stage scoring for seizure severity [21].

- Behavioral Hyperexcitability Test: Standardized assessment including approach response, touch response, loud noise response, and pick-up response with categorical scoring [21].

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Epigenetic Disorder Research. This diagram outlines the integrated experimental approaches used to study epigenetic disorders, from animal model development through molecular phenotyping and functional assessment to data integration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Epigenetic Disorder Investigation

| Reagent/Resource | Specific Example | Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetically Engineered Animal Models | Mecp2-null rat (TALEN-generated) | RTT pathophysiology studies | 10bp deletion in Mecp2; confirmed protein depletion |

| Viral Vector Systems | AAV-SYN-Mbd3-GFP | Neuronal-specific overexpression | Synapsin promoter for neuron-specific expression; GFP tag for visualization |

| Antibodies for Epigenetic Marks | Anti-MeCP2; anti-5mC; anti-5hmC; anti-H3K4me3; anti-H3K36me3 | Western blot, ChIP, immunostaining | Validation in KO models essential for specificity |

| Affinity Purification Systems | Ni-NTA resin for His-tagged MeCP2 | Mass spectrometry interaction studies | Utilizes endogenous His residues in MeCP2 (a.a. 366-372) |

| Behavioral Assessment Tools | PTZ kindling; open-field; hyperexcitability test | Seizure susceptibility and anxiety measurement | Standardized scoring systems (Racine stages for seizures) |

| Epigenomic Editing Tools | CRISPR/dCas9-DNMT3A; dCas9-TET1 | Targeted methylation/demethylation | Causality testing for specific epigenetic marks |

| Bioinformatic Software | DEXseq (splicing); ChIP-seq analyzers | Omics data analysis | Specialized packages for exon usage and epigenetic mark distribution |

Congenital disorders arising from mutations in epigenetic regulator genes represent a paradigm of neurodevelopmental diseases where disrupted interpretation of epigenetic marks leads to profound neurological deficits. The mechanistic insights gained from studying MeCP2 in Rett syndrome, DNMT3A in overgrowth syndrome, and MBD proteins in epileptogenesis reveal both shared and distinct pathological pathways. Common themes include the disruption of neuronal maturation, synaptic function, and network stability, ultimately leading to characteristic neurological and psychiatric symptoms.

The experimental methodologies outlined—from animal models and proteomic analyses to advanced behavioral assessments—provide a framework for continued investigation into these complex disorders. Importantly, research in this area not only elucidates disease mechanisms but also identifies potential therapeutic targets. For instance, the discovery that seizures themselves transiently elevate Mbd3 levels suggests a potential vicious circle in epileptogenesis that could be targeted therapeutically [21]. Similarly, understanding MeCP2's role in alternative splicing opens possibilities for RNA-targeted therapies [17].

As research progresses, the integration of multiple omics datasets and development of more precise epigenetic editing tools will further unravel the complexity of these disorders. The ultimate goal remains developing targeted interventions that can modify disease progression and improve quality of life for individuals affected by these congenital disorders of the epigenetic machinery.

The developing brain is exquisitely sensitive to environmental inputs during critical neurodevelopmental windows. Early-life experiences—including stress, exposure to environmental toxicants, and the quality of maternal care—interface with the genome through epigenetic mechanisms to shape brain development and function. These mechanisms, including DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNAs, fine-tune gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence, thereby acting as a biological interface between the environment and the genome. This whitepaper synthesizes current evidence demonstrating how these environmental factors induce persistent epigenetic changes in the brain, with significant implications for neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs) and psychiatric diseases. A detailed understanding of these processes provides novel targets for therapeutic intervention and drug development aimed at reversing or mitigating environmentally-induced epigenetic disruptions.

The mammalian epigenome comprises a complex network of molecular mechanisms that regulate gene expression and are particularly plastic during developmental periods. The three primary epigenetic mechanisms include:

- DNA methylation: The covalent addition of a methyl group to the 5-carbon of cytosine residues, primarily in CpG dinucleotides, typically associated with transcriptional repression when occurring in promoter regions [13]. This modification is catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) and can be actively reversed by Ten-eleven translocation (TET) enzymes through oxidation [23] [13].

- Histone modifications: Post-translational modifications to histone proteins, including acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination, which alter chromatin structure and DNA accessibility [23] [13]. For example, histone acetylation generally promotes an open chromatin state and active transcription, while specific methylation patterns (e.g., H3K9me3, H3K27me3) are associated with gene repression [13].

- Non-coding RNAs: RNA molecules that regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally (e.g., microRNAs) or participate in chromatin remodeling (e.g., long non-coding RNAs) [24] [13].

The postnatal maturation of the epigenome coincides with critical periods of brain development, including synaptogenesis and circuit refinement, making this period particularly vulnerable to environmental perturbations [13]. Epigenetic mechanisms thus serve as a molecular bridge linking early-life environmental exposures to long-term changes in brain function and disease susceptibility [23] [4].

Early-Life Stress and Epigenetic Reprogramming

Early-life stress (ELS) encompasses various adverse experiences during prenatal, perinatal, and pre-pubertal periods, including maternal separation, physical abuse, and emotional neglect [24] [25]. ELS induces long-term phenotypic adaptations that increase vulnerability to a host of neuropsychiatric disorders, including depression, anxiety, and schizophrenia [24] [26] [25].

ELS Effects on the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis

A primary mechanism through which ELS exerts its effects is by disrupting the development and regulation of the HPA axis, the body's central stress response system [25].

- Glucocorticoid Receptor (GR/NR3C1): ELS is associated with increased DNA methylation of the GR promoter in the hippocampus, leading to reduced GR expression and impaired negative feedback of the HPA axis, resulting in prolonged stress responses [26] [13]. This phenomenon has been consistently demonstrated in both rodent models and human studies [26].

- Other Stress-Related Genes: ELS also alters epigenetic marks on genes encoding corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), FKBP5, and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), further contributing to a dysregulated stress phenotype that persists into adulthood [26] [25].

Cell-Type-Specific Effects

Recent research highlights that ELS induces cell-type-specific epigenetic changes in distinct neural cell populations, including neurons, microglia, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes [24]. For example, ELS can alter microglial epigenomes, affecting their phagocytic activity and synaptic pruning functions, which may contribute to aberrant neural connectivity observed in NDDs [24]. Most historical studies examined heterogenous brain tissue, potentially masking cell-specific changes that are crucial for understanding the full pathophysiological picture [24].

Table 1: Key Epigenetic Modifications Induced by Early-Life Stress

| Target | Epigenetic Change | Functional Outcome | Associated Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|

| GR (Nr3c1) | ↑ DNA methylation in hippocampus [26] | ↓ GR expression, HPA axis dysregulation [26] | Increased stress susceptibility [26] |

| BDNF | ↑ DNA methylation (Mouse Hippocampus) [27] | ↓ BDNF expression [27] | Impaired learning & memory [26] |

| CRH | Altered DNA methylation [25] | ↑ CRH expression, HPA axis hyperactivity [25] | Anxiety-like behavior [25] |

| 5-HT1AR | Altered histone modifications in VTA [26] | Dysregulated serotonergic signaling [26] | Depression-like behavior [26] |

Environmental Toxicants and the Neuroepigenome

A diverse array of environmental chemicals has been shown to modify the epigenome, with significant implications for neurodevelopment. Key neurotoxicants include metals (e.g., arsenic, cadmium, lead, methylmercury), air pollutants, endocrine disruptors, and persistent organic pollutants [27] [28].

Metals

Metals can interfere with epigenetic processes, primarily through the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that can disrupt the function of epigenetic regulatory enzymes [27].

- Arsenic: Exposure is linked to global DNA hypomethylation, as well as gene-specific hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes like p53 [27]. Arsenic also alters histone modifications (e.g., increased H3K9 dimethylation) and miRNA expression profiles [27].

- Cadmium: This carcinogenic metal reduces global DNA methylation by non-competitively inhibiting DNMT activity, potentially leading to oncogene activation [27].

- Methylmercury: In mouse hippocampus, methylmercury exposure increases DNA methylation of the Bdnf gene, resulting in reduced BDNF expression and associated neurotoxicity [27].

Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals (EDCs)

- Bisphenol A (BPA): Prenatal BPA exposure in mice decreases DNA methylation at the Agouti gene and CabpIAP retrotransposon, affecting coat color and obesity, serving as a visible biomarker of epigenetic dysregulation [27].

- Diethylstilbestrol (DES): In utero exposure to DES is associated with global DNA hypomethylation in the mouse uterus, demonstrating the transgenerational epigenetic impact of EDCs [27].

Table 2: Select Environmental Toxicants and Their Epigenetic Effects

| Toxicant | Class | Epigenetic Alterations | Experimental Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arsenic | Metal | Global DNA hypo-methylation; p53 hypermethylation; Altered histone modifications [27] | Human PBL; Rat liver; A549 cells [27] |

| Cadmium | Metal | Global DNA hypo-methylation; DNMT inhibition [27] | Rat liver cells [27] |

| Methylmercury | Metal | BDNF promoter hypermethylation [27] | Mouse hippocampus [27] |

| Bisphenol A (BPA) | EDC | Agouti gene hypo-methylation [27] | Mouse embryo [27] |

| Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) | Organic Pollutant | LINE-1 & Alu hypo-methylation [27] | Human blood [27] |

Maternal Care and Transgenerational Epigenetic Transmission

The quality of mother-infant interactions represents a powerful environmental factor that can shape the offspring's epigenome and behavior, with effects that can be transmitted across generations [29].

Rodent Models of Maternal Licking and Grooming (LG)

In rats, natural variations in maternal care, specifically high versus low licking and grooming (LG), have been linked to stable epigenetic differences in offspring [29].

- Glucocorticoid Receptor (GR) Programming: Offspring of Low LG mothers show increased DNA methylation and decreased histone acetylation at the GR promoter in the hippocampus, resulting in reduced GR expression and heightened HPA stress responses in adulthood [29]. Cross-fostering studies confirm that these effects are directly related to the postnatal care received rather than genetic inheritance [29].

- Estrogen Receptor α (ERα) and Maternal Behavior: In the medial preoptic area (MPOA), differences in maternal LG are associated with differential DNA methylation of the Esr1 gene, which encodes ERα. Female offspring of Low LG dams show increased Esr1 promoter methylation, reduced ERα expression, and subsequently exhibit low LG behavior toward their own offspring, demonstrating a mechanism for the behavioral transmission of maternal care across generations [29].

Primate and Human Studies

Evidence from rhesus macaques shows that abusive parenting styles are transmitted across generations, with over 50% of abused infants becoming abusive mothers [29]. Similarly, human studies indicate an intergenerational transmission of maternal care and attachment styles, with epigenetic mechanisms proposed as a likely mediator [29].

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Assessing DNA Methylation

- Bisulfite Sequencing: The gold standard for detecting DNA methylation at single-base resolution. Genomic DNA is treated with sodium bisulfite, which converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils (read as thymines in sequencing), while methylated cytosines remain unchanged. This is followed by PCR amplification and sequencing [23].

- Methylated DNA Immunoprecipitation (MeDIP): An antibody-based method to enrich for methylated DNA fragments, which can then be analyzed by microarray (MeDIP-chip) or sequencing (MeDIP-seq) to profile genome-wide methylation patterns [23].

- Locus-Specific Methylation Analysis: Methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes or pyrosequencing can be applied for quantitative analysis of specific CpG sites within candidate genes (e.g., NR3C1, BDNF) [29] [26].

Analyzing Histone Modifications

- Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP): This protocol involves cross-linking proteins to DNA, shearing chromatin, and immunoprecipitating DNA-protein complexes using antibodies specific to a histone modification of interest (e.g., H3K9ac, H3K4me3). The co-precipitated DNA is then purified and analyzed by qPCR (ChIP-qPCR) or sequencing (ChIP-seq) to map the genomic localization of the modification [23] [13].

Animal Models of Early-Life Adversity

- Maternal Separation (MS): Rat or mouse pups are separated from the dam for prolonged periods (e.g., 3 hours daily) during the early postnatal period (typically Postnatal Day [PND] 1-14). This model reliably induces long-term changes in HPA axis function, behavior, and epigenetics [26] [25].

- Limited Bedding/Nesting Material: An model of ELS that fragments maternal care and induces unpredictable maternal behavior, leading to robust anxiety-like phenotypes and epigenetic changes in offspring [24].

- Cross-Fostering: A critical experimental design where pups born to mothers of one phenotype (e.g., Low LG) are fostered to mothers of the opposite phenotype (e.g., High LG) at birth. This allows researchers to disentangle the effects of postnatal care from in utero or genetic factors [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Neuroepigenetics Research

| Reagent / Assay | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| DNMT Inhibitors | Chemical inhibition of DNA methylation to test functional consequences. | 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine (Decitabine) [23] |

| HDAC Inhibitors | Chemical inhibition of histone deacetylases to increase histone acetylation. | Trichostatin A (TSA), Sodium Butyrate [23] [13] |

| Site-Specific Epigenetic Editing | CRISPR/dCas9 systems fused to epigenetic "writers" or "erasers" to manipulate specific loci. | dCas9-DNMT3a (targeted methylation), dCas9-TET1 (targeted demethylation) [13] |

| Antibodies for ChIP | Immunoprecipitation of specific histone modifications. | Anti-H3K9ac, Anti-H3K4me3, Anti-H3K27me3 [23] [13] |

| Methylation-Sensitive Restriction Enzymes | Detection and quantification of DNA methylation at specific loci. | HpaII, Mspl [29] |

| Cell-Type-Specific Isolation Kits | Isolation of specific neural cell types for epigenomic profiling. | Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) or immunopanning kits for neurons, microglia, astrocytes [24] |

Signaling Pathways and Conceptual Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate core concepts and experimental pathways discussed in this whitepaper.

Diagram 1: Epigenetic Mechanisms Regulating Gene Expression in Neurons

Diagram 2: HPA Axis Epigenetic Programming by Early-Life Stress

Diagram 3: Transgenerational Transmission of Maternal Care

The evidence is compelling that early-life environmental factors—including stress, toxicant exposure, and maternal care—interface with the genome through epigenetic mechanisms to shape brain development and confer risk for NDDs. These findings have profound implications for drug development and therapeutic strategies. The reversible nature of epigenetic marks presents a promising opportunity for targeted pharmacological interventions. Existing drugs that modulate the epigenome, such as HDAC inhibitors, are being explored for neurological and psychiatric applications [23] [13]. Furthermore, the development of CRISPR-based epigenetic editing tools allows for precise manipulation of specific epigenetic marks at defined genomic loci, offering unprecedented potential for both mechanistic research and future therapeutics [13].

Future research must prioritize cell-type-specific analyses to fully elucidate the complex epigenetic landscape of the brain [24], investigate the potential for transgenerational epigenetic inheritance of neurodevelopmental risk [29], and explore the interactions between different environmental exposures (e.g., the combined impact of ELS and toxicants). A deeper understanding of how the environment sculpts the neuroepigenome will not only advance fundamental knowledge but also pave the way for novel diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders.

Epigenetic mechanisms are fundamental regulators of gene expression during mammalian brain development, acting as a critical interface between the genome and environmental influences [13] [4]. Two phenomena—genomic imprinting and X-chromosome inactivation—serve as paradigmatic models for understanding how epigenetic regulation shapes neural development and function [30]. These processes demonstrate how stable, heritable patterns of gene expression can be established without altering the underlying DNA sequence, primarily through DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNAs [30] [13].

The significance of these epigenetic mechanisms extends profoundly into human disease, particularly neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs). Research has established that defective epigenetic regulation contributes to various NDDs, including autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability, and rare genetic syndromes such as Prader-Willi (PWS) and Angelman (AS) syndromes [4]. These conditions, affecting 7-14% of children in developed countries, share common origins in disrupted brain development and often involve epigenetic dysregulation [4]. PWS and AS specifically represent the foremost examples of imprinting disorders in humans, originating from the same chromosomal region but demonstrating strikingly different phenotypes based on parent-of-origin effects [31] [32].

This review examines the molecular mechanisms of genomic imprinting and X-chromosome inactivation, with particular emphasis on their roles in PWS and AS pathogenesis. We further explore current diagnostic methodologies, experimental models, and emerging therapeutic strategies that target epigenetic pathways, providing a comprehensive resource for researchers and clinical investigators in neurodevelopmental genetics.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Epigenetic Regulation

Molecular Composition of the Epigenetic Machinery

The epigenome comprises several interconnected regulatory systems that collectively establish and maintain cell-type-specific gene expression patterns. These include:

DNA methylation: The covalent addition of a methyl group to the 5' carbon of cytosine bases, predominantly at CpG dinucleotides, catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) [13]. DNMT3A and DNMT3B establish de novo methylation patterns, while DNMT1 maintains these patterns during cell division. DNA demethylation is actively mediated by ten-eleven translocation (TET) enzymes, which catalyze the oxidation of 5-methylcytosine (5mC) to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) and further derivatives [13]. DNA methylation typically silences gene expression when present in promoter regions, though gene body methylation can have activating effects [13].

Histone modifications: Histone proteins undergo numerous post-translational modifications at their N-terminal tails, including acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination [13]. These modifications constitute a complex "histone code" that influences chromatin structure and gene accessibility. For example, histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation (H3K4me3) is associated with active transcription, while H3K27me3 marks facultative heterochromatin and gene repression [13]. These modifications are written by "writer" enzymes (e.g., histone acetyltransferases, methyltransferases) and erased by "eraser" enzymes (e.g., histone deacetylases, demethylases) [13].

Non-coding RNAs: Regulatory RNA molecules, including long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs), influence gene expression through transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms [30] [33]. These RNAs contribute to epigenetic silencing complexes, alternative splicing regulation, and chromatin modification, with approximately 40% of lncRNAs exhibiting brain-specific expression [34].

Chromatin remodeling: ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes regulate nucleosome positioning and accessibility, enabling dynamic changes in chromatin architecture during development [13].

Table 1: Key Epigenetic Modifications and Their Functional Consequences

| Modification Type | Molecular Effect | Functional Outcome | Associated Enzymes |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA methylation | Cytosine modification at CpG islands | Transcriptional repression (promoter); activation (gene body) | DNMT1, DNMT3A/B, TET1-3 |

| Histone acetylation | Neutralization of histone charge | Chromatin relaxation; transcriptional activation | HATs, HDACs |

| H3K4me3 | Histone tail methylation | Transcriptional activation | KMT2 family |

| H3K27me3 | Histone tail methylation | Transcriptional repression | EZH2 (PRC2 complex) |

| H3K9me3 | Histone tail methylation | Constitutive heterochromatin formation | KMT1 family |

Genomic Imprinting: Parent-of-Origin Gene Expression

Genomic imprinting represents a specialized form of epigenetic regulation characterized by monoallelic gene expression dependent on parental origin [30]. This process involves approximately 100-200 genes in mammals, many of which are organized into clusters and play critical roles in growth, development, and metabolic regulation [30] [32]. Imprinting is established during gametogenesis through parent-specific epigenetic marks, primarily DNA methylation at differentially methylated regions (DMRs) [30]. These marks are maintained throughout somatic development but erased and reestablished in the germline, creating an intergenerational cycle of epigenetic inheritance [32].

Imprinted genes display several characteristic features: they often reside in clusters spanning hundreds of kilobases, typically include at least one non-coding RNA transcript, and exhibit allele-specific association with covalent DNA and histone modifications [30]. The regulation of these domains is coordinated by imprinting control regions (ICRs), which often coincide with germline DMRs and function as epigenetic switches that determine parental identity [30].

X-Chromosome Inactivation: Dosage Compensation in Females

X-chromosome inactivation (XCI) represents another fundamental epigenetic process that ensures dosage compensation between females (XX) and males (XY) through transcriptional silencing of one X chromosome in female somatic cells [30]. Two forms of XCI exist: imprinted XCI, which preferentially silences the paternal X chromosome in extraembryonic tissues, and random XCI, which occurs in embryonic lineages and randomly silences either the maternal or paternal X chromosome [30].

The X-inactivation center (XIC) coordinates this process, producing the long non-coding RNA Xist that coats the future inactive X chromosome and recruits chromatin-modifying complexes to establish heterochromatin [30] [33]. Similar to imprinted loci, XCI demonstrates how epigenetic mechanisms can establish stable, heritable states of gene expression across large chromosomal domains, providing insights that extend to genome-wide regulatory principles [30].

The 15q11-q13 Imprinted Locus: Molecular Architecture and Regulation

Genomic Organization and Imprinted Genes

The 15q11-q13 region represents one of the most extensively characterized imprinted loci in the human genome, spanning approximately 5-6 Mb on the proximal long arm of chromosome 15 [32]. This region contains a complex array of imprinted genes that exhibit parent-of-origin-specific expression, with profound implications for neurodevelopment [32] [35].

The locus is flanked by breakpoint regions (BP1-BP3) that predispose to recurrent structural rearrangements, particularly interstitial deletions of approximately 6 Mb that represent the most common etiology for both PWS and AS [32] [35]. The transcriptional activity of genes within this domain is primarily regulated by an imprinting control region (ICR) located upstream of the SNURF-SNRPN promoter, which governs the parent-specific epigenetic status across the entire locus [32] [35].

Table 2: Key Genes in the 15q11-q13 Imprinted Locus

| Gene/Element | Parental Expression | Function | Association with PWS/AS |

|---|---|---|---|

| SNORD116 | Paternal | snoRNA cluster; potential regulator of RNA modification and splicing | Primary candidate for PWS core phenotype |

| SNORD115 | Paternal | snoRNA cluster; potential regulator of serotonin receptor splicing | Modifier of PWS phenotype |

| MKRN3 | Paternal | Zinc finger protein; putative ubiquitin ligase | Contributes to PWS phenotype |

| MAGEL2 | Paternal | Melanoma antigen family; involved in protein trafficking | Contributes to PWS phenotype, including sleep disturbances |

| NDN | Paternal | Necdin; neuronal growth suppressor | Contributes to PWS phenotype |

| UBE3A | Maternal (in neurons) | E3 ubiquitin ligase; targets proteins for degradation | Primary cause of AS when mutated or deleted |

| UBE3A-ATS | Paternal | Antisense transcript; silences paternal UBE3A | Therapeutic target for AS |

| GABRB3/GABRA5/GABRG3 | Biallelic | GABA receptor subunits; inhibitory neurotransmission | Contribute to seizure risk and neuropsychiatric features |

Epigenetic Regulation of the PWS/AS Locus

The 15q11-q13 locus exhibits sophisticated epigenetic regulation that dictates allele-specific expression patterns. The PWS-ICR functions as the master control element, displaying differential methylation established during gametogenesis: the paternal allele is hypomethylated and transcriptionally active, while the maternal allele is hypermethylated and silenced [32] [35]. This differential methylation pattern is maintained throughout development and governs the expression of paternally expressed genes across the locus.