Environmental Exposures and Transgenerational Epigenetic Inheritance: Mechanisms, Evidence, and Therapeutic Implications

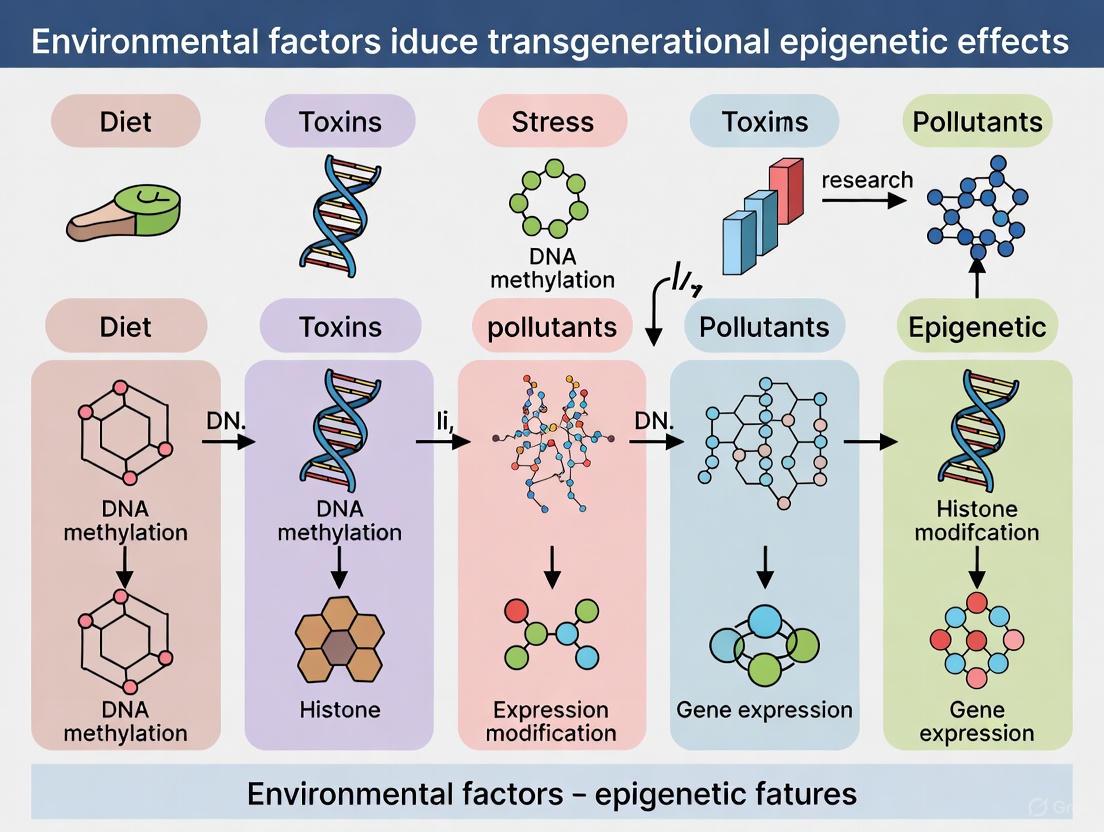

This article synthesizes current research on how environmental factors—including toxicants, nutrition, and stress—induce epigenetic modifications that can be transmitted across generations, influencing disease susceptibility in unexposed descendants.

Environmental Exposures and Transgenerational Epigenetic Inheritance: Mechanisms, Evidence, and Therapeutic Implications

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on how environmental factors—including toxicants, nutrition, and stress—induce epigenetic modifications that can be transmitted across generations, influencing disease susceptibility in unexposed descendants. We explore foundational molecular mechanisms such as DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNAs, alongside methodological approaches for studying transgenerational inheritance in model organisms and human populations. The content critically addresses challenges in establishing causality and confounding factors, compares evidence across species, and examines emerging epigenetic therapies and their potential for clinical translation. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review provides a comprehensive framework for understanding environmentally induced epigenetic transgenerational inheritance and its profound implications for disease etiology and therapeutic innovation.

Unraveling the Core Mechanisms of Environmentally Induced Epigenetic Inheritance

The concept that environmental exposures can influence the health of subsequent generations represents a significant shift in our understanding of inheritance and disease etiology. While genetic inheritance follows Mendelian principles based on DNA sequence, epigenetic inheritance involves the transmission of non-genetic molecular information that regulates gene expression [1]. This whitepaper delineates the critical distinctions between intergenerational and transgenerational epigenetic inheritance, two distinct phenomena with profound implications for biomedical research and therapeutic development.

Environmental epigenetics provides a mechanistic link between ancestral exposures and phenotypic outcomes in descendants, with growing evidence that factors including toxicants, diet, and stress can induce epigenetic changes that persist across generations [1] [2]. Understanding the precise definitions and experimental requirements for establishing each type of inheritance is fundamental for researchers designing studies to investigate the heritable effects of environmental exposures.

Definitions and Key Distinctions

The terms "intergenerational" and "transgenerational" inheritance are often conflated but describe fundamentally different biological scenarios. The distinction hinges on whether the generation in question was directly exposed to the original environmental stressor or whether the effect persists in generations beyond any direct exposure.

Intergenerational Epigenetic Inheritance

Intergenerational epigenetic inheritance refers to the transmission of epigenetic information from directly exposed parents to their directly exposed offspring [3] [1]. This occurs when the environmental exposure affects not only the parent but also the germ cells and/or the developing offspring.

- Maternal Exposure: When a pregnant female (F0 generation) is exposed, both her developing fetus (F1 generation) and the primordial germ cells within that fetus (which will give rise to the F2 generation) are directly exposed [3] [1]. Therefore, observations of epigenetic phenotypes in the F1 and F2 offspring are considered intergenerational effects.

- Paternal Exposure: When a male (F0 generation) is exposed, his developing sperm (F1 generation) is directly exposed. Consequently, effects observed in the resulting F1 offspring are intergenerational [3].

Transgenerational Epigenetic Inheritance

Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance is defined as the germline transmission of epigenetic information between generations in the absence of any direct environmental exposure [1]. This phenomenon requires demonstrating effects in generations that were never exposed to the original stimulus.

- Maternal Exposure Lineage: For exposure to a gestating female (F0), the F3 generation is the first considered transgenerational, as the F2 generation germ cells were directly exposed [3] [1].

- Paternal Exposure Lineage: For exposure to a male (F0), the F2 generation is the first considered transgenerational, as the F1 generation germ cells were directly exposed [3] [1].

Table 1: Key Differences Between Intergenerational and Transgenerational Inheritance

| Feature | Intergenerational Inheritance | Transgenerational Inheritance |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Transmission to directly exposed generations | Transmission to non-exposed generations |

| Generational Scope (Maternal Exposure) | F0, F1, and F2 | F3 and beyond |

| Generational Scope (Paternal Exposure) | F0 and F1 | F2 and beyond |

| Presence of Direct Exposure | Yes | No |

| Primary Mechanism | Direct effect of exposure on germ cells and/or fetus | Stable, inherited alteration of the germline epigenome |

Diagram 1: Generational exposure boundaries. For paternal exposure, the F2 generation is the first transgenerational. For maternal exposure, the F3 generation is the first transgenerational.

Biological Mechanisms and Germline Reprogramming

The potential for epigenetic information to be transmitted across generations hinges on its ability to bypass extensive epigenetic reprogramming events that occur during gametogenesis and early embryonic development [4] [5].

Epigenetic Reprogramming Waves

In mammals, two major waves of epigenetic reprogramming occur:

- Post-Fertilization Reprogramming: Shortly after fertilization, the parental genomes undergo widespread DNA demethylation to reset the epigenome and establish totipotency [4] [5]. This process is asymmetric, with the paternal genome undergoing more rapid, active demethylation.

- Primordial Germ Cell (PGC) Reprogramming: A second, more extensive wave of demethylation occurs in developing PGCs, erasing most DNA methylation marks, including genomic imprints, which are then re-established in a sex-specific manner [1] [4] [5].

For transgenerational inheritance to occur, epigenetic marks must evade both of these reprogramming events. Certain genomic regions, such as those containing transposable elements (e.g., IAP retrotransposons) and some imprinted control regions, are known to be resistant to reprogramming, providing potential vectors for epigenetic transmission [5] [6].

Molecular Carriers of Epigenetic Information

The molecular substrates that can carry epigenetic information across generations include:

- DNA Methylation: Cytosine methylation in CpG dinucleotides is the most extensively studied epigenetic mark. While most methylation is erased during reprogramming, specific loci can retain differential methylation that is transmitted to the next generation [1] [2].

- Histone Modifications: Post-translational modifications to histone tails (e.g., methylation, acetylation) can influence chromatin structure and gene expression. Sperm retain a small fraction of their genome associated with histones, providing a potential mechanism for transgenerational transmission [1] [5].

- Non-Coding RNAs (ncRNAs): Various RNA species, including microRNAs (miRNAs), piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs), and other small non-coding RNAs, are present in sperm and oocytes and can influence embryonic development [1] [5]. For instance, altered miRNA profiles in the sperm of mice subjected to early-life trauma have been correlated with behavioral and metabolic changes in offspring [5].

Diagram 2: Mechanisms of epigenetic inheritance. Environmental exposures alter the germline epigenome. For effects to be transmitted, these marks must escape two major waves of epigenetic reprogramming.

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Establishing robust evidence for transgenerational epigenetic inheritance, particularly in mammals, requires carefully controlled multi-generational studies [1] [2]. The following section outlines standard protocols and key reagents.

Standardized Transgenerational Inheritance Study Design

The most prevalent model for investigating environmentally induced epigenetic transgenerational inheritance uses rodents, typically rats.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Transgenerational Epigenetic Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Animal Models | Outbred (e.g., Sprague-Dawley) or Inbred Rats | Provides a controlled genetic background to distinguish epigenetic from genetic effects. |

| Environmental Toxicants | Vinclozolin [1], Plastics (BPA, Phthalates) [2], Jet Fuel (JP8) [2], Glyphosate [2] | Used as exposure agents to induce epigenetic changes in the germline. |

| Epigenetic Analysis Kits | Methylated DNA Immunoprecipitation (MeDIP) Kits [2], Bisulfite Conversion Kits | For genome-wide or locus-specific analysis of DNA methylation patterns. |

| Antibodies | Anti-5-Methylcytosine (5-mC), Anti-Histone Modification (e.g., H3K27me3) | For immunoprecipitation-based enrichment of epigenetically modified DNA or chromatin. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing | MeDIP-Seq, Whole Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS), RNA-Seq | For high-resolution, genome-wide mapping of epigenetic marks and transcriptomes. |

Protocol: Rodent Transgenerational Study

F0 Generation Exposure:

- Subject: Gestating female rats.

- Timing: Expose transiently during the critical window of fetal gonadal sex determination (e.g., embryonic days 8-14 in rats) [1] [2]. This timing is crucial as it coincides with the epigenetic reprogramming and remethylation of the primordial germ cells of the F1 generation.

- Route: Administration can be via injection, oral gavage, or diet, depending on the toxicant.

Breeding Scheme to Generate Unexposed Generations:

- Breed exposed F0 females to unexposed control males to produce F1 offspring. Both maternal and paternal lineages can be studied.

- F1 Generation: At adulthood (~3 months), breed F1 animals within the exposure lineage (but avoiding sibling crosses to prevent inbreeding) to produce the F2 generation.

- F2 Generation: At adulthood, breed F2 animals to produce the F3 generation [2].

- A parallel control lineage is maintained without any exposure.

Phenotypic Assessment:

- Age F1, F2, and F3 generation animals to adulthood (e.g., 1 year) to allow for late-onset diseases to manifest.

- Conduct thorough histological and pathological analyses of tissues, commonly focusing on the testis, prostate, kidney, and ovaries, and assess for conditions like obesity and tumor development [1] [2].

Epigenetic Analysis:

- Collect sperm from F1, F2, and F3 males.

- Perform epigenome-wide analysis, such as MeDIP-Seq (Methylated DNA Immunoprecipitation followed by Sequencing) to identify Differential DNA Methylation Regions (DMRs) [2].

- Correlate the presence of specific DMRs in the germline with the disease phenotypes in the somatic tissues of the same individuals and their offspring.

Diagram 3: Standard rodent experimental design. The F3 generation is the first truly transgenerational cohort in this maternal exposure model.

Evidence from Animal Studies

Numerous studies have demonstrated that exposure to various environmental toxicants can promote the transgenerational inheritance of disease. For example:

- Vinclozolin: Exposure of a gestating F0 female to this agricultural fungicide led to increased spermatogenic cell apoptosis, decreased sperm count, and other reproductive abnormalities in the F1-F3 generations [1]. The F3 generation exhibited specific DMRs in their sperm, confirming a transgenerational epigenetic effect.

- Plastics Mixture (BPA and Phthalates): Ancestral exposure was associated with transgenerational inheritance of testis disease and ovarian abnormalities, correlated with unique sets of sperm DMRs [2].

- Jet Fuel (JP8) and Dioxin: These exposures have been linked to transgenerational increases in the incidence of prostate and kidney disease, as well as obesity, with each toxicant producing a distinct set of pathology-associated DMRs [2].

Critical Considerations and Challenges

The field of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance in mammals continues to evolve, with several areas requiring critical attention.

- Distinguishing Causation from Correlation: A significant challenge is proving that transmitted epigenetic marks are the cause of the phenotype, rather than a consequence of it or a parallel phenomenon [6]. Integration with genetic models and epigenetic editing tools (e.g., CRISPR-based systems that target DNA methylation) is helping to address this.

- Rigorous Experimental Design: Proper controls and avoidance of inbreeding or genetic drift are essential. The use of outbred animal strains and large sample sizes helps to ensure that observed effects are epigenetic rather than genetic [2].

- Escape from Reprogramming: The mechanisms by which specific sequences evade epigenetic reprogramming are not fully understood. Loci rich in transposable elements and those with specific sequence contexts may be more prone to retaining marks [5] [6].

- Evidence in Humans: While epidemiological studies in humans suggest patterns consistent with transgenerational epigenetic inheritance (e.g., the effects of grandparental nutrition on grandchildren's health), definitive proof in humans is inherently difficult to obtain due to confounding variables and the long generation times [7] [8]. Current evidence remains correlative.

The precise distinction between intergenerational and transgenerational epigenetic inheritance is fundamental for designing and interpreting studies on the heritable effects of environmental exposures. While intergenerational effects involve direct exposure, transgenerational inheritance provides evidence for a stable, germline-mediated propagation of epigenetic information.

Future research will focus on:

- Elucidating the precise molecular mechanisms that allow epigenetic information to bypass reprogramming.

- Utilizing epigenome editing tools to establish causal links between specific epigenetic marks and phenotypic outcomes.

- Expanding multi-omics approaches that integrate DNA methylomics, histoneomics, and transcriptomics from both somatic and germ cells.

- Translating findings from model organisms to human health via carefully designed Epigenome-Wide Association Studies (EWAS).

Understanding these forms of inheritance is no longer a purely academic pursuit but has direct implications for drug development, toxicology risk assessment, and public health policy, as it suggests that the environmental experiences of one generation can have a lasting legacy on the health of generations to come.

Epigenetic memory enables the persistence of distinct gene expression patterns in different cell types despite a common genetic code, serving as a fundamental mechanism for maintaining cellular identity, immune response, and brain function throughout an organism's lifespan [9]. This molecular "memory" allows cells to record past environmental exposures, developmental cues, and metabolic experiences into stable transcriptional programs that can be maintained across multiple cell divisions and, in some cases, even transmitted to subsequent generations. The stability of epigenetic memory arises from a self-reinforcing network of chemical modifications to DNA and histone proteins, coupled with regulatory non-coding RNAs that together establish and maintain heritable patterns of gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence [9] [10]. Understanding these mechanisms is particularly crucial in the context of environmental epigenetics, where external factors can induce epigenetic changes that may have transgenerational consequences for health and disease susceptibility [11] [12].

The molecular machinery of epigenetic memory operates through three principal, interconnected mechanisms: DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNAs. These systems form a complex regulatory network with positive feedback loops that can both recapitulate traditional binary memory paradigms and generate more nuanced analog memory states [9]. This review comprehensively examines each of these mechanisms, their crosstalk, experimental approaches for their investigation, and their role in mediating the transgenerational effects of environmental exposures, thereby providing researchers and drug development professionals with a foundational understanding of this rapidly advancing field.

Core Mechanisms of Epigenetic Memory

DNA Methylation: The Stable Epigenetic Mark

DNA methylation represents one of the most stable and well-characterized epigenetic modifications, involving the covalent addition of a methyl group to the 5-carbon position of cytosine bases, primarily within CpG dinucleotides [13]. This modification is catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), with DNMT3A and DNMT3B establishing de novo methylation patterns, while DNMT1 maintains these patterns during DNA replication through its preference for hemi-methylated DNA [14]. The stability of DNA methylation is counterbalanced by active demethylation processes mediated by ten-eleven translocation (TET) enzymes, which catalyze the oxidation of 5-methylcytosine (5mC) to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) and further oxidized derivatives, ultimately leading to base excision repair and replacement with unmethylated cytosine [14].

The genomic distribution of DNA methylation is non-random and functionally significant. Promoters and first exons of actively expressed genes are typically unmethylated, while transposable elements and imprinted genes are densely methylated to maintain genomic stability and parental-specific expression patterns [14]. Interestingly, methylation within gene bodies can sometimes correlate with active expression and influence alternative splicing [14]. The stability of DNA methylation through cell division contributes significantly to the long-term maintenance of gene expression states, making it a crucial component of epigenetic memory [14]. However, contrary to earlier assumptions, DNA methylation can be dynamic in certain contexts, particularly in the brain, where neuronal activity can trigger rapid changes in methylation status at genes regulating synaptic plasticity [14].

Table 1: DNA Methylation Machinery and Functions

| Component | Type | Primary Function | Role in Memory |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNMT1 | Enzyme | Maintenance methylation during cell division | Preserves methylation patterns across cell generations |

| DNMT3A/B | Enzyme | De novo methylation establishment | Initiates new methylation patterns in response to stimuli |

| TET1-3 | Enzyme | Active demethylation through oxidation | Provides dynamism and erasure capability |

| 5-Methylcytosine (5mC) | Modified base | Transcriptional repression when in promoters | Stable silencing of alternative gene programs |

| 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) | Modified base | Intermediate in demethylation; enriched in brain | Potential "primed" state for plasticity |

| MeCP2/MBD1-4 | Reader proteins | Recognize methylated DNA and recruit effectors | Translate methylation into chromatin compaction |

Histone Modifications: The Plastic Dimension

Histone modifications provide a more dynamic and versatile layer of epigenetic regulation through post-translational modifications to the N-terminal tails of histone proteins around which DNA is wrapped in nucleosomes [14]. These modifications include acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and increasingly recognized monoaminylation (e.g., dopaminylation, serotonylation) [14]. The combinatorial nature of these modifications creates what has been termed a "histone code" with enormous information capacity, enabling fine-tuned regulation of chromatin structure and function [14].

The establishment of histone modifications is catalyzed by "writer" enzymes such as histone acetyltransferases (HATs), histone methyltransferases (HMTs), and kinases, while their removal is facilitated by "eraser" enzymes including histone deacetylases (HDACs), lysine demethylases (KDMs), and phosphatases [14]. Specific histone modifications are associated with distinct chromatin states: histone acetylation generally neutralizes the positive charge of histones, reducing DNA-histone affinity and promoting an open chromatin structure permissive for transcription [14]. Histone methylation effects depend on the specific residue and degree of methylation, with H3K4me3 associated with active transcription, H3K27me3 with facultative heterochromatin, and H3K9me3 with constitutive heterochromatin [14].

The bistable behavior of histone modification circuits forms a fundamental mechanism for epigenetic memory. Mathematical modeling of the mutually inhibitory circuit between H3K4me3 (activating) and H3K9me3 (repressing) demonstrates that when autocatalytic feedback is strong relative to dilution rates, the system exhibits bistability with two stable steady states corresponding to active and silenced transcriptional states [9]. This creates a biological switch that "remembers" its initial state, enabling persistent maintenance of gene expression patterns despite signal withdrawal [9].

Diagram 1: Histone modification circuit demonstrating bistability. The mutual inhibition between H3K4me3 and H3K9me3, combined with autocatalytic feedback, creates a bistable system when dilution rate (ε) is low, enabling binary epigenetic memory.

Table 2: Major Histone Modifications and Their Functional Consequences

| Modification | Chromatin State | Transcriptional Effect | Writer Enzymes | Eraser Enzymes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 | Euchromatin | Activation | KMT2 family, SET1A/B | KDM5 family |

| H3K9me3 | Heterochromatin | Repression | KMT1 family, SUV39H1/2 | KDM4 family, KDM3A/B |

| H3K27me3 | Facultative Heterochromatin | Repression | PRC2 (EZH2) | KDM6 family |

| H3K36me3 | Gene Bodies | Elongation, Splicing | KMT3 family, SETD2 | KDM4 family |

| H3/H4 Acetylation | Open Chromatin | Activation | HATs (p300, CBP) | HDACs (1-11) |

| H3S10ph | Mitotic Chromatin | Condensation | Aurora B kinase | PP1 phosphatase |

Non-Coding RNAs: Guides and Regulators

Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) represent a diverse class of RNA molecules that do not encode proteins but play crucial roles in epigenetic regulation by guiding chromatin-modifying complexes to specific genomic loci, influencing chromatin architecture, and regulating mRNA stability and translation [10] [14]. They are broadly categorized into small ncRNAs (including microRNAs and siRNAs) and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) based on size and biogenesis pathways [10]. These molecules serve as dynamic regulators that can respond rapidly to environmental signals and establish sustained epigenetic states.

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) demonstrate particularly sophisticated mechanisms of epigenetic regulation. For instance, Xist lncRNA orchestrates X-chromosome inactivation by recruiting repressive chromatin-modifying complexes, while Tsix RNA serves as its antisense regulator [15]. Similarly, Fos extra-coding RNA (ecRNA) has been shown to directly inhibit DNMT3A activity in neurons, leading to hypomethylation of the Fos gene and contributing to long-term fear memory formation [15]. The mechanism involves Fos ecRNA binding to the tetramer interface of DNMT3A, inhibiting its methylation activity in a dominant manner even in the presence of histone tails and regulatory proteins like DNMT3L [15]. Single-molecule fluorescent in situ hybridization has revealed that Fos ecRNA and mRNA transcripts are correlated at the single-cell level and accumulate at actively transcribed genomic regions in neurons [15].

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) contribute to epigenetic memory by fine-tuning the expression of chromatin-modifying enzymes and transcription factors. In autoimmune diseases, consistent patterns of miRNA dysregulation have been observed, including increased expression of miR-21, miR-148a, and miR-155, and decreased expression of miR-146a [16]. These alterations are associated with hypomethylation of proinflammatory gene loci, reduction of repressive histone marks, and increased chromatin accessibility at promoters of genes driving pathogenic T cell responses [16]. Experimental manipulation of these non-coding RNAs can attenuate disease-associated epigenetic and functional changes, supporting their causal role in maintaining pathological epigenetic states [16].

Interplay of Epigenetic Mechanisms in Memory Formation

The true sophistication of epigenetic memory emerges from the multilayered crosstalk between DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNAs, creating a self-reinforcing regulatory network that stabilizes gene expression patterns. This crosstalk establishes positive feedback loops that enable epigenetic states to be maintained through cell divisions long after the initial triggering signal has dissipated [9].

The relationship between repressive histone modifications and DNA methylation exemplifies this crosstalk. H3K9me3 recruits HP1 proteins, which in turn promote the binding of DNMT3A, leading to DNA methylation [9]. Conversely, DNA methylation can be recognized by methyl-CpG binding domain proteins (MBDs), which recruit histone deacetylases and methyltransferases to reinforce a repressive chromatin state [9] [14]. Similarly, the mutual antagonism between H3K4me3 and H3K9me3 creates a bistable system that can exist in either an active or repressed state with minimal intermediate states, effectively functioning as a biological switch [9].

Non-coding RNAs often serve as guides and scaffolds in this crosstalk. For example, at the onset of X-chromosome inactivation, the loss of H3K4me2, H4 acetylation, and gain of H3K27me3 on one X chromosome attenuate Tsix RNA expression and activate Xist expression [15]. The continuing presence of H3K4me2, H4 acetylation, and Tsix RNA expression on the active X chromosome sequesters DNMT3A and directs its activity to silence Xist expression [15]. This illustrates how the interplay between histone modifications and non-coding RNAs can direct DNA methylation patterns to establish stable epigenetic states.

The emerging understanding of this crosstalk has revealed that epigenetic memory is not simply binary but can exhibit analog properties depending on circuit architecture. Systems with strong positive feedback between repressive histone modifications and DNA methylation tend toward binary all-or-nothing memory, while systems lacking such feedback may display graded, analog memory responses [9]. This spectrum of memory properties enables epigenetic regulation to encode both stable cell fate decisions and more plastic, tunable responses to environmental stimuli.

Transgenerational Epigenetic Inheritance of Environmental Exposures

The concept of epigenetic memory extends beyond somatic cell inheritance to encompass transgenerational epigenetic inheritance, where environmental exposures can induce epigenetic changes in germ cells that persist across multiple generations [12]. This phenomenon represents a nongenetic mechanism of inheritance that may explain the persistence of certain disease susceptibilities and phenotypic traits across generations.

Paternal Environmental Exposures

Accumulating evidence demonstrates that paternal preconceptual exposures to various environmental factors can significantly influence offspring health and development through epigenetic mechanisms [12]. These effects encompass a spectrum from diet and nutrition to environmental pollutants, stress, substance use, and infections. Paternal obesity, for instance, alters sperm microRNA content and is associated with metabolic dysfunction in female offspring, including impaired glucose tolerance and insulin resistance [12]. Similarly, paternal exposure to bisphenol A (BPA), a prevalent environmental pollutant found in plastics, induces testicular and sperm pathologies in mouse offspring and impairs glucose tolerance in female offspring, potentially through altered Igf2 epigenetic status in sperm [17] [12].

The molecular mechanisms underlying paternal epigenetic inheritance involve several interconnected pathways. These include changes in sperm DNA methylation patterns, histone modifications retained in sperm (particularly in regions resistant to protamine replacement), and alterations in sperm RNA content, including microRNAs, tRFs (tRNA-derived fragments), and other small non-coding RNAs that can directly influence embryonic development [12]. For example, paternal stress exposure alters sperm microRNA content and reprograms offspring HPA stress axis regulation, leading to increased stress sensitivity in offspring [12]. These sperm-borne RNAs are delivered to the oocyte during fertilization and can directly influence embryonic gene expression and development [12].

Bisphenol A as a Case Study in Epigenetic Disruption

Bisphenol A (BPA) provides a compelling case study of how environmental exposures can disrupt epigenetic regulation across generations. BPA exposure has been associated with neurotoxicity and epigenetic dysregulation throughout successive generations, with long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) serving as particularly susceptible targets [17]. Using Drosophila melanogaster and mice as model organisms, research has demonstrated that BPA drives the dysregulation of lncRNAs, which in turn mediate changes in gene expression with implications for reproductive and neurodevelopmental outcomes [17].

The transgenerational effects of BPA exposure illustrate the complex interplay between environmental toxicants and epigenetic mechanisms. Paternal BPA exposure in mice has been shown to impair glucose tolerance in female offspring and damage testicular junctional proteins transgenerationally [12]. These effects are associated with oxidative stress and epigenetic changes in sperm that are transmitted to subsequent generations. Research also indicates that natural compounds may have potential in mitigating BPA-induced health risks, particularly concerning neurological development, while the promotion of BPA-free alternatives and reduced plastic consumption represent important public health strategies [17].

Diagram 2: Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance pathway. Paternal environmental exposures induce epigenetic alterations in sperm that can influence offspring phenotype across multiple generations through various molecular mechanisms.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

DNA Methylation Analysis Techniques

The analysis of DNA methylation patterns employs a range of techniques with varying resolution, throughput, and applications. Bisulfite sequencing remains the foundational approach, leveraging the selective deamination of unmethylated cytosine to uracil by sodium bisulfite, while 5-methylcytosine residues remain unconverted [13]. After PCR amplification and sequencing, uracils are read as thymine, allowing direct inference of methylation status at single-nucleotide resolution [13].

Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) provides the most comprehensive view of cytosine methylation, covering nearly all CpG sites in the genome and enabling absolute quantification at each cytosine [13]. This method has been extensively employed in large-scale epigenome mapping projects such as ENCODE, NIH Roadmap Epigenomics, and IHEC [13]. However, WGBS is resource-intensive, requiring high sequencing depth (>30× for diploid methylation calling) and suffering from reduced sequence complexity due to bisulfite-induced DNA damage [13].

Reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) offers a cost-effective alternative by focusing sequencing efforts on CpG-rich regions through methylation-insensitive restriction enzyme digestion (typically MspI) combined with size selection [13]. This approach enables efficient profiling of approximately 4 million CpG sites in the human genome, making it well-suited for large-cohort studies and clinical diagnostics [13]. However, RRBS has limitations in genome coverage, excluding distal enhancers, low-CpG-density intergenic regions, and repetitive elements that may harbor functionally relevant methylation changes [13].

Table 3: DNA Methylation Profiling Techniques

| Method | Resolution | Coverage | Throughput | Key Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) | Single-base | Genome-wide | Low | Reference methylomes, discovery | High cost, DNA damage, computational complexity |

| Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS) | Single-base | CpG-rich regions | Medium | Large cohorts, clinical diagnostics | Limited to restriction enzyme sites, misses regulatory regions |

| Methylation Arrays (e.g., EPIC) | Single-CpG | 850,000 sites | High | Epidemiological studies, biomarker validation | Targeted coverage only, probe design biases |

| Targeted Bisulfite Sequencing | Single-base | User-defined | Medium | Validation studies, clinical assays | Requires prior knowledge, limited discovery power |

| Oxidative Bisulfite Sequencing | Single-base | Genome-wide | Low | 5hmC quantification, neuroepigenetics | Technically challenging, specialized protocols |

Histone Modification Profiling

Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) represents the gold standard for genome-wide mapping of histone modifications and chromatin-associated proteins [13]. This technique involves cross-linking proteins to DNA, immunoprecipitation with antibodies specific to particular histone modifications, and high-throughput sequencing of the bound DNA fragments [13]. ChIP-seq enables the identification of genomic regions enriched for specific histone marks, providing insights into the chromatin landscape associated with gene regulation.

The successful application of ChIP-seq depends critically on antibody specificity and efficiency, with validation being essential for data interpretation [13]. Recent advancements include low-input and single-cell ChIP-seq protocols, which have expanded applications to rare cell populations and heterogeneous tissues [13]. Additionally, the combination of ChIP-seq with other epigenomic methods, such as ATAC-seq for chromatin accessibility, provides a more comprehensive view of chromatin states and their relationship to gene regulation.

Non-Coding RNA Analysis

The analysis of non-coding RNAs involves both sequencing-based and targeted approaches. RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) provides an unbiased, genome-wide view of ncRNA expression, enabling the discovery of novel ncRNAs and the detection of differential expression across conditions [13]. Specialized library preparation protocols have been developed to capture specific ncRNA classes, such as small RNAs and lncRNAs, which have distinct biogenesis and properties compared to mRNA [13].

For functional characterization, techniques such as single-molecule fluorescent in situ hybridization (smFISH) enable visualization of individual ncRNA transcripts at the single-cell level, providing spatial information and revealing heterogeneity within cell populations [15]. As demonstrated in studies of Fos ecRNA, smFISH has revealed correlations between ecRNA and mRNA transcript numbers in individual neurons and their response to neuronal activation [15]. Experimental manipulation of ncRNAs through knockdown, overexpression, or mutagenesis, combined with phenotypic assessment, helps establish causal relationships between ncRNA expression and functional outcomes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Epigenetic Memory Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Methyltransferases | Recombinant DNMT1, DNMT3A, DNMT3B, DNMT3L | Catalyze DNA methylation; study enzyme kinetics | In vitro methylation assays, structural studies, inhibitor screening |

| Histone Modification Enzymes | HATs (p300, CBP), HDACs (1-11), HMTs (EZH2), KDMs | Add or remove histone modifications | Enzyme characterization, drug discovery, in vitro chromatin reconstitution |

| Specific Antibodies | Anti-5mC, Anti-5hmC, Histone modification-specific antibodies | Detect and enrich epigenetic marks | Immunoprecipitation, immunofluorescence, Western blot, validation |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits | EZ DNA Methylation kits, MethylCode kits | Convert unmethylated cytosine to uracil | Sample preparation for bisulfite sequencing, methylation analysis |

| CRISPR/dCas9 Epigenetic Editors | dCas9-DNMT3A, dCas9-TET1, dCas9-p300 | Targeted epigenetic modulation | Locus-specific epigenetic manipulation, functional validation |

| HDAC/DNMT Inhibitors | 5-Azacytidine, Vorinostat, Decitabine | Pharmacological inhibition of epigenetic enzymes | Epigenetic erasure studies, cancer epigenetics, combination therapies |

| Chromatin Assembly Systems | Recombinant histones, chromatin assembly factors | Reconstitute chromatin in vitro | Biochemical studies of chromatin dynamics, transcription assays |

The molecular mechanisms of epigenetic memory—DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNAs—represent an integrated regulatory system that enables cells to stably maintain gene expression patterns in response to developmental and environmental signals. The crosstalk between these systems creates self-reinforcing circuits that can exhibit both binary switching behavior and analog tuning of transcriptional states [9]. Understanding these mechanisms is particularly crucial in environmental epigenetics, where exposures to factors such as BPA can induce epigenetic changes with potential transgenerational consequences [17] [12].

Future research in epigenetic memory will likely focus on several key areas. First, the development of single-cell multi-omics approaches will enable the characterization of epigenetic heterogeneity within tissues and the dynamics of epigenetic memory establishment and maintenance at unprecedented resolution [16]. Second, the continued refinement of epigenetic editing technologies, particularly CRISPR/dCas9-based systems, will allow more precise manipulation of specific epigenetic marks to establish causal relationships between epigenetic states and functional outcomes [13]. Finally, the translation of epigenetic knowledge into clinical applications, including epigenetic biomarkers for disease risk and progression, and epigenetic therapies for reversing maladaptive epigenetic states, represents a promising frontier for personalized medicine [13] [18].

The field of epigenetic memory continues to evolve rapidly, with technological advances enabling increasingly sophisticated investigations into how environmental experiences become biologically embedded and potentially transmitted across generations. This knowledge not only deepens our understanding of basic biology but also opens new avenues for addressing complex diseases influenced by gene-environment interactions throughout the lifespan and across generations.

The field of epigenetics has revolutionized our understanding of how environmental factors influence gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence. Epigenetic mechanisms represent a critical interface between environmental exposures and genomic function, providing a biological framework for understanding how toxicants, nutritional stress, and psychological trauma can induce lasting changes in cellular function and organismal health [19]. These mechanisms include DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNA-mediated regulation, all of which modulate chromatin structure and transcriptional accessibility [20] [21].

A particularly significant concept in this domain is the exposome, which encompasses all environmental exposures an individual encounters throughout their lifetime and their corresponding biological effects [22]. As Andrea Baccarelli, M.D., Ph.D., from Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health notes, "We now recognize that our health is shaped by a combination of many exposures, both negative and positive" [22]. This holistic perspective is essential for understanding complex disease etiologies that cannot be explained by single exposures alone.

The capacity of environmental triggers to induce transgenerational epigenetic effects represents a paradigm shift in our comprehension of disease inheritance and susceptibility. While the evidence for such inheritance is more established in plants and invertebrates, research in mammals and humans suggests that some environmentally-induced epigenetic marks can evade the extensive epigenetic reprogramming that occurs during gametogenesis and early embryogenesis [23] [5]. This whitepaper examines the mechanisms by which major environmental triggers induce epigenetic changes, with particular focus on implications for transgenerational inheritance and disease susceptibility.

Fundamental Epigenetic Mechanisms

DNA Methylation

DNA methylation involves the addition of a methyl group to cytosine bases, primarily at cytosine-phosphate-guanine (CpG) sites, catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) [20] [21]. This modification typically leads to gene silencing by physically preventing transcription factor binding or by recruiting proteins that promote chromatin condensation [20]. During tumorigenesis, for instance, global hypomethylation coincides with localized hypermethylation of tumor suppressor gene promoters, leading to their inactivation [21].

A specialized form of this mechanism, the CpG Island Methylator Phenotype (CIMP), describes the simultaneous hypermethylation of multiple CpG island promoters, which can silence transcriptional genes or inactivate DNA repair genes and tumor suppressor genes, driving tumor development [21]. The enzymes DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B work in concert to establish and maintain these methylation patterns, with DNMT1 preserving existing methylation states during DNA replication, while DNMT3A and DNMT3B mediate de novo methylation [21].

Histone Modifications

Histone modifications encompass post-translational changes to histone proteins, including acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination [20] [5]. These modifications alter chromatin structure and DNA accessibility, thereby influencing gene expression. For example, histone acetylation generally promotes an open chromatin state conducive to transcription, while certain methylation patterns can either activate or repress gene expression depending on the specific residues modified [20].

The importance of histone modifications is exemplified by their role in stress responses. In Drosophila embryos exposed to heat stress over generations, phosphorylation of ATF-2 (dATF-2) alters heterochromatin assembly, an epigenetic event maintained over multiple generations before gradually returning to baseline [5].

Non-Coding RNAs

Non-coding RNAs, including microRNAs (miRNAs) and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), regulate gene expression through sequence-specific interactions with target mRNAs, typically leading to their degradation or translational repression [20] [5]. These molecules have emerged as crucial mediators of epigenetic inheritance, particularly in transgenerational responses to environmental stressors.

In mice subjected to unpredictable maternal separation and stress (MSUS), altered miRNA expression in sperm was associated with behavioral changes and metabolic alterations that persisted across multiple generations [5]. Similarly, in C. elegans, starvation-induced survival mechanisms involving the RNAi pathway and regulation of small RNAs can be inherited across generations, effectively creating a "memory" of dietary history [5].

Table 1: Key Epigenetic Modification Types and Their Functions

| Modification Type | Molecular Mechanism | Primary Functions | Environmental Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Methylation | Addition of methyl group to cytosine bases at CpG sites | Gene silencing, genomic imprinting, X-chromosome inactivation | High sensitivity to nutritional factors, toxins, psychological stress |

| Histone Modifications | Post-translational modifications (acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation) of histone tails | Chromatin remodeling, transcriptional regulation, DNA repair | Responsive to environmental stressors, metabolic state |

| Non-coding RNAs | RNA molecules that regulate gene expression without being translated into proteins | mRNA degradation, translational repression, transcriptional silencing | Altered by various stressors, including trauma and toxicants |

Diagram 1: Environmental triggers and their epigenetic pathways, showing how different stressors influence specific mechanisms leading to functional changes and potential inheritance.

Toxicants as Epigenetic Inducers

Mechanisms of Toxin-Induced Epigenetic Alterations

Environmental toxicants, including air pollutants, endocrine disruptors, heavy metals, and recreational substances such as tobacco smoke and alcohol, can induce profound epigenetic changes through multiple mechanisms [19]. These toxicants often directly interact with epigenetic regulatory machinery, modifying the activity of DNMTs, histone-modifying enzymes, and RNA interference pathways.

Notably, many toxins trigger oxidative stress responses that subsequently alter the epigenetic landscape. For example, arsenic exposure has been shown to induce transgenerational effects on learning and memory in rats through a crosstalk between arsenic methylation, hippocampal metabolism, and histone modifications [24]. Similarly, nicotine exposure in male mice produces behavioral impairment across multiple generations of descendants, suggesting stable inheritance of nicotine-induced epigenetic marks [24].

Transgenerational Inheritance of Toxicant-Induced Effects

The potential for transgenerational epigenetic inheritance of toxicant-induced effects remains a subject of intense investigation and debate. In mammals, efficient epigenetic reprogramming during gametogenesis and early embryogenesis typically erases most acquired epigenetic marks [23]. However, some marks may evade this reprogramming, particularly those located at genomic regions resistant to demethylation, such as centromeric satellites and imprinted loci [5].

A critical consideration in this field is distinguishing between true transgenerational inheritance versus intergenerational effects. Intergenerational effects involve direct exposure of the germline (F1 generation) when a pregnant F0 female is exposed, affecting the F2 generation. In contrast, transgenerational effects manifest in the F3 generation and beyond without direct exposure [5]. While compelling examples exist in plants and invertebrates, evidence in mammals is more limited. The Agouti mouse model represents one of the best-characterized examples, where variable DNA methylation at a transposon inserted near a coat color gene shows modest heritability [6].

Table 2: Selected Toxicants and Their Documented Epigenetic Effects

| Toxicant Category | Specific Examples | Documented Epigenetic Changes | Potential Health Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Air Pollutants | Particulate matter, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons | Altered global DNA methylation, histone modifications in stress response genes | Respiratory diseases, cardiovascular impairment, accelerated aging |

| Heavy Metals | Arsenic, lead, cadmium | DNA methylation changes in genes involved in oxidative stress response and DNA repair | Cognitive deficits, cardiovascular disease, increased cancer risk |

| Endocrine Disruptors | Bisphenol A, phthalates | Altered methylation of genes involved in hormonal signaling and development | Reproductive disorders, metabolic syndrome, developmental abnormalities |

| Recreational Substances | Tobacco smoke, alcohol | Genome-wide DNA methylation changes, histone modifications in addiction-related pathways | Addiction, cardiovascular disease, cancer, behavioral disorders |

Nutritional Stress and Epigenetic Modulation

Prenatal and Early-Life Nutritional Programming

Early life represents a period of exceptional epigenetic plasticity, during which nutritional factors can establish lasting epigenetic patterns that influence health trajectories into adulthood [20]. The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) hypothesis formalizes this concept, proposing that early life nutritional conditions program an individual's disease risk in later life [25].

According to DOHaD principles, the developing fetus utilizes environmental cues, including nutrient availability, to determine an optimal phenotype for survival in the anticipated postnatal environment. However, when a mismatch occurs between prenatal predictions and actual postnatal conditions, this programming becomes maladaptive, increasing disease risk [25]. This nutritional programming is mediated through epigenetic mechanisms that establish stable gene expression patterns.

Specific Nutritional Influences on Epigenetic Machinery

Specific nutrients directly participate in epigenetic modifications as methyl donors, enzyme co-factors, or metabolic regulators. Methyl donors such as folate, choline, and betaine provide methyl groups for DNA and histone methylation reactions. Micronutrients including vitamin B12, zinc, and selenium serve as essential cofactors for epigenetic enzymes such as DNMTs and histone deacetylases (HDACs).

The relationship between nutrition and epigenetics is bidirectional; while nutrients influence epigenetic states, epigenetic mechanisms also regulate nutrient metabolism. For instance, DNA methylation patterns of metabolic genes can influence how individuals respond to dietary interventions, contributing to the variable effectiveness of nutritional therapies across populations [26].

Psychological Trauma as an Epigenetic Inducer

Neurobiological Pathways Linking Trauma and Epigenetics

Psychological trauma, particularly during sensitive developmental windows, can induce stable epigenetic changes that shape long-term mental and physical health outcomes [20] [24]. The primary neurobiological pathway mediating this relationship is the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which regulates stress response through glucocorticoid signaling [20].

Early life stress and trauma exposure have been associated with DNA methylation changes in key HPA axis regulatory genes, including the glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) and FKBP5 [20]. These epigenetic modifications alter HPA axis function, leading to either hyperactive or blunted stress responses that predispose individuals to psychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [20] [24].

The diathesis-stress model provides a framework for understanding how genetic vulnerabilities interact with environmental stressors, with epigenetic mechanisms serving as the molecular interface of this interaction [24]. This model suggests that individuals with genetic predispositions to mental illness may require specific environmental triggers to manifest the disorder, with epigenetic changes mediating this process.

Intergenerational and Transgenerational Transmission of Trauma

Emerging evidence suggests that the epigenetic effects of psychological trauma may extend across generations. A groundbreaking 2025 study with three generations of Syrian refugee families identified distinct epigenetic signatures of violence exposure across generations, including germline-associated differential methylation [25]. This study compared families with different timing of violence exposure (1980 vs. 2011) and found 14 differentially methylated positions associated with germline exposure and 21 with direct violence exposure [25].

Notably, most of these differentially methylated positions showed the same directionality in DNA methylation changes across germline, prenatal, and direct exposures, suggesting a common epigenetic response to violence [25]. The study also identified epigenetic age acceleration in children with prenatal exposure to violence, highlighting the particular vulnerability of the in utero developmental period [25].

Animal models provide mechanistic insights into how trauma-induced epigenetic changes might be transmitted. In mice, chronic psychosocial stress alters DNA methylation patterns in male germ cells, with these changes potentially transmitted to offspring [24]. Similarly, early trauma in mice (unpredictable maternal separation and stress) leads to altered miRNA expression in sperm and behavioral changes that persist across multiple generations [5].

Diagram 2: Psychological trauma epigenetic pathway, illustrating the neurobiological and molecular mechanisms linking stress exposure to health outcomes and transgenerational effects.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Epigenome-Wide Association Studies (EWAS)

Epigenome-wide association studies (EWAS) have emerged as a powerful approach for identifying epigenetic signatures associated with environmental exposures. These studies typically utilize microarray-based platforms, such as the Illumina EPIC BeadChip which assays over 850,000 CpG sites, to conduct comprehensive DNA methylation analyses across the genome [25].

The Syrian refugee trauma study exemplifies a robust EWAS design, incorporating a three-generation cohort with contrasting developmental exposures to violence—direct exposure, prenatal exposure, and germline exposure [25]. This study employed a two-stage analytic approach: first using robust linear regression to identify differentially methylated positions associated with violence trauma, followed by generalized estimating equations (GEE) to account for family clustering [25]. Significant hits were determined using strict Bonferroni correction for multiple testing (p value < 6.5E-8) [25].

Emerging Technologies and Novel Approaches

Technological advances continue to enhance our ability to detect and interpret epigenetic changes. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) methods now enable base-resolution mapping of DNA methylation, histone modifications, and chromatin accessibility across the entire genome. Single-cell epigenomics is revolutionizing the field by allowing researchers to examine epigenetic heterogeneity within complex tissues and track epigenetic dynamics during development.

Liquid biopsies that analyze extracellular vesicles (EVs) represent another promising approach. As Andrea Baccarelli explains, "Extracellular vesicles are fascinating because they offer a way to study tissues that we can't easily access through traditional methods" [22]. These tiny, membrane-bound vesicles carry molecular messages (RNA, proteins, lipids) that reflect the health and function of their cells of origin, including neurons in the brain, allowing noninvasive assessment of organ-specific epigenetic responses [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Platforms for Epigenetic Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methylation Analysis Platforms | Illumina EPIC BeadChip, whole-genome bisulfite sequencing | Genome-wide DNA methylation profiling, differential methylation analysis | Coverage limitations (BeadChip) vs. comprehensive mapping (sequencing) |

| Histone Modification Tools | ChIP-seq kits, histone modification-specific antibodies | Mapping histone modifications genome-wide, quantifying specific marks | Antibody specificity critical, requires high-quality chromatin preparation |

| Non-coding RNA Analysis | Small RNA sequencing, miRNA microarrays | Profiling miRNA and other small non-coding RNAs | Specialized library preparation needed for small RNAs |

| Sample Preservation | PAXgene Blood RNA tubes, FFPE tissue protocols | Preserving epigenetic marks in clinical samples | FFPE can cause nucleic acid fragmentation requiring specialized repair protocols |

| Data Analysis Platforms | R/Bioconductor packages, specialized EWAS software | Statistical analysis of epigenetic data, correcting for cell type heterogeneity | Computational intensity varies by approach, cell type deconvolution often necessary |

Implications for Drug Development and Therapeutic Interventions

Epigenetic Biomarkers in Clinical Applications

Epigenetic biomarkers offer significant potential for advancing clinical practice, particularly in the realms of disease diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment monitoring [26]. These biomarkers provide several advantages over genetic markers, including their dynamic nature, responsiveness to environmental influences, and ability to provide functional information about gene regulation [26].

In oncology, several epigenetic biomarkers have already been translated to clinical use. The SEPT9 methylation test (Epi proColon) for colorectal cancer detection demonstrates how DNA methylation signatures can be leveraged for non-invasive cancer screening [21]. Similarly, CDO1 gene hypermethylation shows promise as a diagnostic marker for multiple cancer types, detectable in various body fluids including plasma and urine [21].

Beyond cancer, epigenetic biomarkers hold potential for assessing mental health risks and treatment responses. Research indicates that changes in gene expression within limbic brain regions associated with depression and stress-related disorders involve aberrant epigenetic regulation [24]. Furthermore, antidepressant medications may exert their therapeutic effects, at least partially, through epigenetic mechanisms [24].

Epigenetic-Targeted Therapeutics

The reversible nature of epigenetic modifications makes them attractive targets for therapeutic intervention. Epigenetic drugs currently in clinical use primarily target DNA methyltransferases (e.g., azacitidine, decitabine) and histone deacetylases (e.g., vorinostat, romidepsin) [21]. However, these first-generation epigenetic therapies lack specificity, leading to broad genome-wide effects and significant side effects.

Next-generation epigenetic therapies aim for greater precision by targeting specific readers, writers, or erasers of epigenetic marks. The development of precision environmental health (PEH) approaches represents a complementary strategy, focusing on preventing environmentally-induced epigenetic changes before they contribute to disease pathogenesis [22]. As Andrea Baccarelli explains, "True health develops during the months, years, and lifetime before someone gets a diagnosis — the times when we are best poised to intervene" [22].

Diagram 3: Germline reprogramming and epigenetic inheritance, showing mechanisms by which epigenetic marks escape erasure and the strength of evidence across species.

Environmental triggers—including toxicants, nutritional stress, and psychological trauma—function as potent epigenetic inducers that shape disease susceptibility and health trajectories across the lifespan. The emerging evidence for transgenerational epigenetic inheritance of environmentally-induced effects represents a fundamental shift in our understanding of heredity, suggesting that ancestral experiences can influence offspring biology without changes to DNA sequence.

While the field has made remarkable progress, significant challenges remain. The mammalian germline undergoes extensive epigenetic reprogramming, creating formidable barriers to transgenerational inheritance [23] [6]. Many reported effects in mammals are actually intergenerational rather than truly transgenerational, reflecting direct exposure of the germline rather than stable inheritance across multiple unexposed generations [5]. Furthermore, as noted in a 2024 critical perspective, "the evidence for many potentially important forms of environmentally induced epigenetic inheritance remains inconclusive" [6].

Future research directions should prioritize standardized methodologies for assessing transgenerational epigenetic inheritance, improved epigenetic editing tools for causal validation, and expanded longitudinal multi-generational cohorts in human populations. The development of an "epigenetic score meter"—a tool that can disentangle the relationship between genetic and environmental influences—represents a promising approach for advancing precision medicine applications [24].

As the field evolves, integrating epigenetic perspectives into public health strategies offers the potential to move beyond treatment toward genuine prevention of environmentally-mediated diseases. By understanding how environmental triggers become biologically embedded through epigenetic mechanisms, we can develop more effective interventions to promote health across generations.

Epigenetic reprogramming in the mammalian germline involves two extensive waves of genome-wide DNA demethylation to reset epigenetic information for totipotency. However, specific genomic regions resist this erasure, retaining epigenetic marks that can be transmitted transgenerationally. This whitepaper examines the molecular mechanisms that enable certain epigenetic signatures to escape developmental reprogramming, focusing on the characteristics of resistant genomic loci and the experimental evidence supporting this phenomenon. Within the context of environmental epigenetics, we explore how exposure to various factors—including toxicants, nutrients, and other stressors—can induce stable epigenetic alterations in the germline that bypass reprogramming barriers. These escaped epimutations are associated with heritable disease susceptibilities and phenotypic changes, presenting novel considerations for drug development and therapeutic targeting.

The mammalian genome undergoes two global epigenetic reprogramming events during early development: first in primordial germ cells (PGCs), the precursors to sperm and eggs, and second in the pre-implantation embryo after fertilization [27] [28]. These reprogramming waves involve massive DNA demethylation through both passive (replication-dependent) and active (enzyme-mediated) mechanisms, erasing most epigenetic marks to restore totipotency and reestablish developmental plasticity [27]. The reprogramming process in PGCs is particularly comprehensive, with global DNA methylation levels decreasing to less than 5%,

Despite this genome-wide erasure, certain genomic regions exhibit resistance to demethylation, maintaining their epigenetic signatures through both reprogramming events [28]. These "escapee" regions include imprinted genes, transposable elements, and other sequences with potential regulatory significance [27] [28]. Environmentally induced epigenetic modifications that strategically locate within these resistant regions can thereby evade erasure and become stably inherited across generations, providing a plausible molecular mechanism for transgenerational epigenetic inheritance (TEI) of acquired traits and disease susceptibilities [2] [29] [28].

Molecular Mechanisms of Epigenetic Escape

DNA Methylation and Demethylation Pathways

DNA methylation primarily occurs at CpG dinucleotides, resulting in 5-methylcytosine (5mC), which is generally associated with transcriptional repression. The DNA methyltransferases DNMT3A and DNMT3B perform de novo methylation, while DNMT1 acts as a maintenance methyltransferase during cell division [27]. Active demethylation involves ten-eleven translocation (TET) enzymes (TET1, TET2, TET3) that oxidize 5mC to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), 5-formylcytosine (5fC), and 5-carboxycytosine (5caC), which can then be excised by thymine-DNA glycosylase (TDG) in conjunction with base excision repair [27].

During PGC development, global demethylation occurs through both active and passive mechanisms. Passive demethylation results from repression of DNMTs and UHRF1 (which directs DNMT1 to replication foci), while active demethylation is associated with increased TET family expression [27]. Human PGCs specifically repress UHRF1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B, while enriching TET1 and TET2 compared to surrounding somatic cells [27].

Genomic Regions Resistant to Reprogramming

The following table summarizes the primary genomic regions and sequence elements that demonstrate resistance to epigenetic reprogramming:

Table 1: Genomic Regions Resistant to Epigenetic Reprogramming

| Resistant Region | Resistance Mechanism | Functional Significance | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Imprinted Genes | Protection from TET-mediated oxidation; histone modifications maintain methylation | Maintain parental-origin-specific expression; crucial for development | Various imprinted loci maintaining differential methylation [28] |

| Transposable Elements (TEs) | Dense methylation prevents reactivation and retrotransposition | Genome stability maintenance | IAP elements in agouti gene [28]; LINE elements in sheep [28] |

| Subtolomeric Regions | Specific chromatin context; positional effects | Chromosome stability | Pericentromeric repeats; subtelomeric regions [28] |

| Low-Complexity Repeats | Unknown; potentially related to chromatin accessibility | Possible role in timing of gene expression during development | Simple sequence repeats in sheep [28] |

| Non-Imprinted Genes | Specific DNA binding factors; histone mark enrichment | Developmental processes; disease susceptibility | Genes affecting growth, fertility, neural development [28] |

Research in sheep models has revealed that a significant proportion (63.5%) of transgenerationally inherited differentially methylated cytosines (DMCs) reside within repetitive element regions, with the majority located in long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs) [28]. This suggests that the genomic and chromatin context significantly influences susceptibility to epigenetic escape.

Experimental Evidence for Escape Mechanisms

Key Studies Demonstrating Epigenetic Escape

Multiple experimental approaches across species have provided compelling evidence for epigenetic escape mechanisms. The following table summarizes pivotal studies in this field:

Table 2: Key Experimental Evidence for Epigenetic Escape Mechanisms

| Study System | Environmental Exposure | Escaped Epigenetic Marks | Transgenerational Phenotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse (Agouti) | Maternal methyl donor diet | DNA methylation at IAP transposon upstream of agouti gene | Altered coat color (yellow), obesity | [28] |

| Mouse (AxinFu) | Methyl donor supplementation | DNA methylation at TE within AxinFu allele | Kinked tail phenotype | [28] |

| Sheep | Paternal methionine supplementation | 107 DMCs in CG, CHH, and CHG contexts | Altered growth traits, male fertility | [28] |

| Rat | Various environmental toxicants (plastics, pesticides, jet fuel) | Disease-specific differential DNA methylation regions (DMRs) in sperm | Kidney disease, prostate disease, testis disease, obesity, pubertal abnormalities | [2] |

| Human PGCs | In vivo development analysis | Specific histone modification patterns (H3K27me3 retention) | Potential impact on germ cell differentiation | [27] |

Characteristics of Escaped Regions in Sheep Model

A detailed analysis of transgenerationally inherited DMCs in a sheep model exposed to paternal methionine supplementation revealed several key characteristics of regions escaping epigenetic reprogramming:

- Genomic Distribution: 65% located in intergenic regions, 33% in intronic regions, and 2% in promoter regions [28]

- Sequence Context: 82 of 107 TEI DMCs (76.6%) were in CG context, 20 (18.7%) in CHH, and 5 (4.7%) in CHG context [28]

- Functional Associations: Genes associated with these escaped regions impact growth, development, male fertility, cardiac disorders, and neurodevelopment [28]

- Neurological Links: Interestingly, 21 of 34 transgenerationally methylated genes have associations with neural development and brain disorders, including autism, schizophrenia, bipolar disease, and intellectual disability, suggesting a potential genetic overlap between brain and infertility disorders [28]

Experimental Protocols for Studying Escape Mechanisms

Methylated DNA Immunoprecipitation Sequencing (MeDIP-Seq)

Purpose: To comprehensively map genome-wide DNA methylation patterns in germ cells and evaluate resistance to reprogramming.

Detailed Methodology:

- Sperm Collection: Collect sperm from F0, F1, F2, and F3 generation males to distinguish transgenerational from intergenerational effects

- DNA Extraction and Fragmentation: Isolate genomic DNA and fragment to 100-500bp using sonication or enzymatic digestion

- Methylated DNA Immunoprecipitation: Incubate fragmented DNA with 5-methylcytosine-specific antibody; pull down immunoprecipitated methylated DNA fragments

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Prepare sequencing libraries from immunoprecipitated DNA; sequence using high-throughput platforms

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Map sequences to reference genome; identify differentially methylated regions (DMRs) with statistical significance; use 1kb DMR size to improve bioinformatics accuracy [2]

Key Considerations: Updated MeDIP procedures with advanced reagents improve reproducibility and accuracy compared to earlier methodologies [2].

Transgenerational Inheritance Study Design

Purpose: To distinguish true transgenerational epigenetic inheritance from intergenerational effects.

Standard Protocol:

- F0 Generation Exposure: Expose gestating female mammals during fetal gonadal development (e.g., embryonic days 8-14 in rats) to environmental factors

- F1 Generation: Breed exposed F0 females to generate F1 offspring; these are directly exposed as germ cells in utero

- F2 Generation: Breed F1 males and females to generate F2 offspring; in females, this represents the first unexposed generation

- F3 Generation: Breed F2 males and females to generate F3 offspring; the first truly transgenerational cohort with no direct exposure [2] [29]

Critical Consideration: True transgenerational inheritance in mammals requires demonstration of inherited phenotypes and epimutations to at least the F3 generation after maternal exposure or F2 after paternal exposure, excluding direct exposure effects [29].

Visualization of Escape Mechanisms

Germline Reprogramming and Escape Pathways

Diagram 1: Germline Reprogramming and Escape Pathways. This diagram illustrates how environmental exposures induce germline epigenetic modifications that face extensive reprogramming in primordial germ cells (PGCs). While most epigenetic marks are erased (green pathway), resistant genomic regions enable epigenetic escape (red pathway), leading to transgenerational inheritance.

Genomic Distribution of Escaped Epimutations

Diagram 2: Genomic Distribution of Escaped Epimutations. This diagram visualizes the genomic distribution and functional impact of transgenerationally inherited differentially methylated cytosines (DMCs) based on data from a sheep nutritional epigenetics study.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Epigenetic Escape

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Methylation Inhibitors | 5-azacytidine, zebularine | Experimental manipulation of DNA methylation | DNMT inhibition; creates hypomethylated state for comparison |

| Methylation Detection Kits | Methylated DNA Immunoprecipitation (MeDIP) kits, bisulfite conversion kits | Mapping genome-wide methylation patterns | Selective enrichment or conversion for methylation analysis |

| TET Enzyme Modulators | Vitamin C (TET activator), TET inhibitors | Manipulating active demethylation pathways | Studying TET-mediated oxidation in reprogramming |

| Antibodies for Epigenetic Marks | 5-methylcytosine, 5-hydroxymethylcytosine, H3K27me3, H3K4me3 | Immunostaining, MeDIP, ChIP experiments | Detection and enrichment of specific epigenetic modifications |

| Bisulfite Sequencing Kits | EZ DNA Methylation kits, Pyrosequencing kits | Single-base resolution methylation analysis | Converting unmethylated cytosines to uracils while preserving methylated cytosines |

| In Vitro PGC Culture Systems | Human PGC-like cells (hPGCLCs) | Modeling early human germline development in vitro | Studying reprogramming dynamics without ethical constraints of human embryos |

Implications for Disease Etiology and Drug Development

The escape of epigenetic marks from germline reprogramming provides a plausible mechanism for the transgenerational inheritance of disease susceptibility. Studies have demonstrated that exposure to various environmental toxicants—including hydrocarbons, dioxins, pesticides, plastics, and herbicides—promotes the epigenetic transgenerational inheritance of pathologies affecting the kidney, prostate, testes, pubertal development, and metabolic function [2]. Importantly, the disease-specific differentially methylated regions (DMRs) in sperm are exposure-specific for each pathology with negligible overlap, suggesting that different environmental exposures influence unique subsets of DMRs and genes to promote the developmental origins of disease [2].

For drug development professionals, these escape mechanisms present both challenges and opportunities. The stable inheritance of epigenetic states suggests that:

- Early-life environmental exposures may create disease susceptibilities that manifest generations later

- Epigenetic biomarkers in sperm may serve as predictors for transgenerational disease risks

- Therapeutic interventions targeting epigenetic modifiers (TET enzymes, DNMTs, histone modifiers) may potentially reverse inherited epimutations

- Drug safety profiles may need to consider potential transgenerational epigenetic effects

The nervous system appears particularly vulnerable to transgenerational epigenetic influences, with numerous studies reporting inherited behavioral phenotypes and stress responses [29]. This aligns with findings that genes escaping reprogramming are enriched for functions in nervous system development and association with brain disorders including autism, schizophrenia, and bipolar disease [28].

Epigenetic escape from germline reprogramming represents a sophisticated molecular mechanism enabling the transgenerational transmission of environmentally acquired information. Specific genomic regions—including imprinted genes, transposable elements, and other sequences with particular chromatin contexts—demonstrate inherent resistance to the extensive DNA demethylation that characterizes PGC development. When environmentally induced epigenetic modifications strategically target these resistant regions, they can bypass reprogramming barriers and become stably inherited across generations.

The growing evidence for this phenomenon necessitates a expanded framework for disease etiology that integrates environmental epigenetics with traditional genetic models. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these escape mechanisms provides critical insights into the molecular basis of transgenerational disease inheritance and potential avenues for therapeutic intervention. Future research should focus on precisely characterizing the molecular signatures of resistant regions, developing more sophisticated models for studying human germline epigenetics, and exploring pharmacological approaches to modulate these inherited epigenetic states.

The field of transgenerational epigenetics has revolutionized our understanding of how environmental exposures can shape health and disease across generations. This paradigm challenges the conventional dogma that inheritance is solely governed by DNA sequence, revealing that environmental factors can induce epigenetic modifications that are transmitted to subsequent generations. These discoveries provide a mechanistic bridge between nature and nurture, explaining how parental and ancestral experiences can influence offspring biology without altering the genetic code itself [30].

This whitepaper examines three foundational research areas that have been instrumental in establishing the principles of environmental epigenetics and transgenerational inheritance. The Agouti mouse model serves as a quintessential epigenetic biosensor, demonstrating how nutritional and chemical exposures during gestation can produce stable, heritable changes in phenotype through DNA methylation alterations. Human studies of the Dutch Hunger Winter cohort provide compelling evidence for fetal metabolic programming in response to prenatal nutritional deprivation. Finally, research on Holocaust survivors and their descendants reveals how severe psychological trauma can leave epigenetic signatures that are transmitted to subsequent generations, altering stress reactivity and social-emotional functioning.

Together, these seminal studies provide a comprehensive framework for understanding how diverse environmental exposures—from nutrients and toxicants to profound psychological stress—can produce lasting epigenetic changes with transgenerational health implications.

The Agouti Mouse Model: An Epigenetic Biosensor

Experimental Model and Molecular Mechanism

The viable yellow agouti (Avy) mouse represents a cornerstone model in environmental epigenetics research. This model centers on a metastable epiallele resulting from the insertion of an intracisternal A particle (IAP), a murine retrotransposon, upstream of the transcription start site of the Agouti gene [30]. The wild-type Agouti gene encodes a paracrine signaling molecule that regulates melanin production, typically resulting in a brown coat with a sub-apical yellow band on each hair shaft.