Enhancing Resolution and Accuracy in Single-Cell Epigenomics: A Guide to Advanced Protocols and Data Analysis

Single-cell epigenomics has revolutionized our understanding of cellular heterogeneity, yet challenges in protocol resolution and data accuracy persist.

Enhancing Resolution and Accuracy in Single-Cell Epigenomics: A Guide to Advanced Protocols and Data Analysis

Abstract

Single-cell epigenomics has revolutionized our understanding of cellular heterogeneity, yet challenges in protocol resolution and data accuracy persist. This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals, exploring the foundational principles, current methodological landscape, and critical optimization strategies for single-cell epigenomic protocols. We delve into the technical and biological challenges—from data scalability to cellular heterogeneity—and present established and emerging solutions, including robust nuclei isolation techniques and advanced multi-omic integrations like snATAC+snRNA and SHARE-seq. Furthermore, we synthesize best practices for data validation and differential analysis, offering a clear pathway to generating more reliable, clinically translatable insights into gene regulation and disease mechanisms.

The Single-Cell Epigenomic Landscape: Defining Resolution and Confronting Current Limitations

Understanding Cellular Heterogeneity and its Impact on Epigenetic Measurements

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Chromatin Accessibility Assays (e.g., ATAC-seq, scATAC-seq)

Q: My ATAC-seq data shows strange fragment size distribution. What should I look for? A: A healthy ATAC-seq fragment size distribution should show distinct peaks at approximately 50 bp (nucleosome-free regions), 200 bp (mononucleosome), and 400 bp (dinucleosome) [1]. The absence of this pattern can indicate over-tagmentation or DNA degradation. If over-tagmentation is suspected (which can mask nucleosomal features while preserving promoter signal), review and optimize the transposition reaction time [1].

Q: What does a low TSS (Transcription Start Site) enrichment score indicate? A: A TSS enrichment score below 6 is a common warning sign [1]. This can reflect poor signal-to-noise ratio or uneven fragmentation across the genome. Note that the baseline for a "good" score can be cell-type dependent, so consulting literature for similar cell types is recommended.

Q: How can I improve differential analysis in scATAC-seq when it doesn't agree with expected biology? A: Discrepancies often stem from how peaks are defined, batch effects, or replicate quality [1]. For single-cell data, avoid a simple "nearest gene" approach for peak assignment, as it ignores chromatin looping [1]. Instead, use cell cluster-specific peak calling to avoid losing signals from rare cell types, and employ normalization methods like TF-IDF (Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency), which is effective for sparse single-cell data [1].

Targeted Enrichment Assays (e.g., CUT&Tag, CUT&RUN, ChIP-seq)

Q: I have a sparse or uneven signal in my CUT&Tag data. Is this normal? A: Yes, CUT&Tag and CUT&RUN data are often sparse and can have low read counts in some regions due to their low-background nature [1]. Peaks called in regions with only 10–15 reads may be false positives. It is crucial to visually inspect your data in a genome browser like IGV and consider merging replicates before peak calling to strengthen your signal [1].

Q: Which peak caller should I use for broad histone marks like H3K27me3? A: Standard peak callers that assume sharp peaks will often fail with broad marks. When using MACS2, ensure you enable broad mode for marks like H3K27me3 and H3K9me3 [1]. This not only adjusts the peak width parameter but also uses a different statistical model tailored for diffuse enrichment.

Q: My experimental replicates show poor agreement. What could be the cause? A: Poor replicate agreement in antibody-based methods is frequently caused by variable antibody efficiency, differences in sample preparation, or PCR bias [1]. Ensure consistent sample handling, use high-quality antibodies validated for the assay, and include an adequate number of replicates for robust statistics.

Single-Cell Specific Challenges

Q: How do I manage the extreme data sparsity in my scATAC-seq dataset? A: Data sparsity is a fundamental challenge, as each cell may have only ~10,000 fragments [1]. To analyze this data, move beyond tools designed for bulk sequencing. Use dimensionality reduction methods like Latent Semantic Indexing (LSI) or normalization strategies like TF-IDF, which are implemented in packages such as ArchR and Signac, to effectively analyze the sparse matrix [1].

Q: The integration between my scATAC-seq and scRNA-seq data seems unreliable. What is the pitfall? A: A common pitfall is blindly trusting computed "gene activity scores" [1]. These scores are typically generated by summing accessibility in regions near a gene's TSS (e.g., ±2 kb) and are not a direct measurement of expression. False correlations can arise if this limitation is not considered. Always validate key findings with orthogonal methods.

Q: How can I quantify epigenetic heterogeneity within a group of cells? A: You can use a dedicated metric like epiCHAOS [2]. This computational tool uses a distance-based approach on binarized single-cell epigenomic data (e.g., scATAC-seq peaks-by-cells matrix) to assign a quantitative heterogeneity score for a defined cluster of cells. It has been validated to reflect biological states, showing higher scores in multipotent stem cells and lower scores in differentiated lineages [2].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Key reagents for single-cell epigenomics experiments.

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| pAG-Tn5 (uncharged) | A fusion protein used for tagmentation in CUT&Tag assays. The "uncharged" version is not pre-loaded with adapters, allowing for custom barcoding [3]. | Ideal for single-cell combinatorial indexing (sciCUT&Tag) where custom barcodes are needed [3]. |

| pAG-Tn5 (loaded) | Pre-loaded with standard sequencing adapters, ready for tagmentation [3]. | Standard CUT&Tag protocols for bulk or single-cell assays [3]. |

| Fluorescent pAG-Tn5 | Loaded with Cy5-tagged adapters, enabling visualization of tagmentation efficiency [3]. | Quality control during CUT&Tag protocol optimization [3]. |

| Custom-loaded pAG-Tn5 | pAG-Tn5 loaded with user-specified adapter sequences [3]. | Advanced applications requiring specific barcodes, such as in spatial profiling or complex multiplexing [3]. |

Standardized Experimental Workflows

Table 2: Overview of common single-cell epigenomic methods.

| Method | Core Principle | Key Application | Throughput & Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|

| sci-ATAC-seq | Uses combinatorial barcoding in multi-well plates to profile chromatin accessibility [4]. | Highly flexible; ideal for mixing multiple samples and for pilot studies to evaluate sample quality [4]. | ~10,000 nuclei per 96-well plate; can be split across samples [4]. |

| 10x Genomics ATAC-seq | Droplet-based microfluidics for profiling chromatin accessibility [4]. | Best for cell lines, clean tissues, or samples with low starting cell numbers [4]. | Input: 15,300 nuclei. Recovery: 5,000-12,000 nuclei per sample. Higher fragments per nucleus than sci-ATAC-seq [4]. |

| Droplet-based scCUT&Tag | Combines CUT&Tag on bulk nuclei with single-cell barcoding via the 10x Genomics platform [3]. | High-throughput profiling of histone modifications (e.g., H3K27me3, H3K4me3) and transcription factors in complex tissues [3]. | Protocols reported for profiling H3K27me3 in human PBMCs and glioblastoma [3]. |

| Combinatorial Indexing sciCUT&Tag | Sequential barcoding of cells using pAG-Tn5 in a split-pool strategy without physical cell separation [3]. | Scalable, cost-effective profiling of chromatin modifications; also enables multi-omic profiling (MulTI-Tag) [3]. | Effective for profiling abundant histone marks in human PBMCs [3]. |

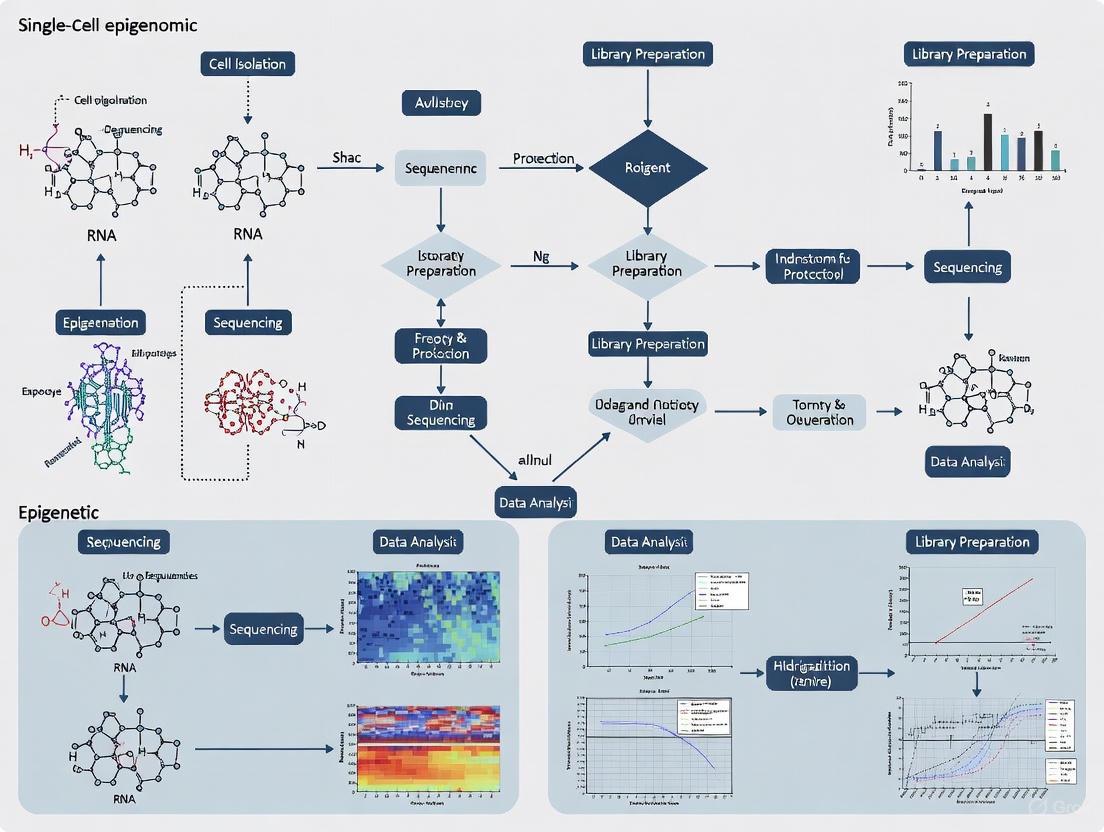

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

General single-cell epigenomics workflow.

Key steps in the CUT&Tag assay.

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ: My single-cell epigenomics data analysis is too slow and uses too much memory. What scalable solutions exist? A major computational bottleneck in analysis is the dimensionality reduction step. Traditional nonlinear dimensionality reduction methods, such as those requiring the construction of a full cell-to-cell similarity matrix, demand memory that increases quadratically with cell count (e.g., ~7 TB for 1 million cells), making them infeasible for large datasets [5].

- Solution: Implement matrix-free spectral embedding algorithms, as in the SnapATAC2 package. This approach uses the Lanczos algorithm to compute eigenvectors without constructing the full similarity matrix, reducing time and space complexity to a linear relationship with the number of cells [5]. This allows for the analysis of hundreds of thousands of cells in a fraction of the time.

FAQ: How can I improve the sensitivity of my scATAC-seq experiments to detect more open chromatin regions per cell? A typical limitation of droplet-based scATAC-seq is sparse genomic coverage, detecting only about 7,000 accessible sites per cell against a background of over 100,000 detectable sites in bulk assays [6].

- Solution: Optimize the Tn5 transposase reaction. Using a hyperactive in-house Tn5 preparation (Tn5-H100 at 83 µg/ml) in a protocol termed "scTurboATAC" resulted in a four-fold higher activity compared to some commercial enzymes. This optimization significantly increases the number of unique fragments per cell and improves the TSS enrichment score, thereby enhancing sensitivity without compromising data quality [6].

FAQ: There is no consensus on the best statistical method for identifying differentially accessible (DA) regions. How can I ensure my findings are robust? A survey of the literature reveals a lack of consensus, with numerous statistical methods in use, and fundamental questions—such as whether to treat scATAC-seq data as qualitative or quantitative—still debated [7].

- Solution: Employ pseudobulk methods. Systematic benchmarking using matched bulk and single-cell ATAC-seq data has shown that methods aggregating cells within biological replicates to form "pseudobulks" consistently rank among the top performers for concordance with ground truth data. Methods like negative binomial regression and certain permutation tests have shown substantially lower concordance [7].

FAQ: How critical is nuclei isolation for successful multiomic single-nucleus assays (e.g., snATAC+snRNA)? The quality of nuclei isolation is a critical first step that profoundly impacts the quality of all downstream sequencing data and the ability to identify cell types [8].

- Solution: For solid tissues like ovarian cancer, a detergent-based nuclei isolation method (e.g., using NP-40) yields superior sequencing results compared to methods involving collagenase tissue dissociation. Always visually assess nuclei quality with a microscope after trypan blue staining to ensure integrity before proceeding to library preparation [8].

Quantitative Data Comparison

Table 1: Benchmarking of Dimensionality Reduction Tools for scATAC-seq Data

| Tool / Algorithm | Underlying Method | Scalability (Time) | Scalability (Memory) | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SnapATAC2 | Matrix-free spectral embedding | Linear with cell number | Linear with cell number (~21 GB for 200k cells) | Fast, memory-efficient, precise for large datasets [5] |

| ArchR / Signac | Linear (LSI / PCA) | Linear with cell number | Low | Computationally efficient, popular [5] |

| cisTopic | Nonlinear (LDA) | Very high runtime growth | High, but not limiting | Effective for complex structures, but slow [5] |

| Original SnapATAC | Nonlinear (Spectral embedding) | High | Quadratic (fails >80k cells) | Pioneering nonlinear method, but not scalable [5] |

| Neural Network Models (e.g., PeakVI) | Nonlinear (Deep Learning) | Slow (e.g., ~4 hours for 200k cells) | Scales with features | Powerful, but requires GPUs and high resources [5] |

Table 2: Impact of Tn5 Transposase Optimization on scATAC-seq Sensitivity

| Experimental Protocol | Tn5 Enzyme Used | Relative Tn5 Activity | Key Quality Metric (Example: Unique Fragments per Cell) | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard scATAC-seq | Tn5-TXGv2 (10x Genomics) | 1x (Baseline) | Baseline | General purpose mapping [6] |

| scTurboATAC | Tn5-H100 (in-house) | ~4x higher than TXGv2 | Significantly Increased | For overcoming data sparsity and improving coverage [6] |

| scMultiome-ATAC | Tn5 with phosphorylated adapters | N/A | Maintained with RNA quality | For simultaneous profiling of ATAC and RNA [6] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: scTurboATAC for Enhanced Sensitivity

Purpose: To increase the number of detected accessible chromatin sites per cell in scATAC-seq experiments, thereby reducing data sparsity. Key Principles: This protocol replaces the standard Tn5 transposase with a more active, custom-loaded enzyme and uses an optimized buffer system [6].

Detailed Methodology:

- Tn5 Preparation: Hyperactive Tn5 transposase is loaded in-house with custom adapters (e.g., using oligonucleotides as listed in Table 1 of the source [6]) to create a high-activity stock (Tn5-H100, 83 µg/ml).

- Nuclei Preparation: Prepare a single-nuclei suspension from your sample (e.g., cell culture or tissue) using standard methods.

- Tagmentation Reaction: Incubate the nuclei with the Tn5-H100 enzyme preparation. Critical: Use the buffer provided in the 10x Genomics scATAC-seq kit, as it was found to yield higher Tn5 activity compared to standard tagmentation buffers [6].

- Downstream Processing: Continue with the standard library preparation steps as per your chosen platform (e.g., 10x Genomics Chromium). The resulting libraries will be sequenced, and the data will show improved fragment counts and TSS enrichment.

Protocol: Reliable Nuclei Isolation for Multiomic Profiling

Purpose: To isolate high-quality nuclei from complex human tissues (e.g., ovarian cancer) for robust snATAC+snRNA sequencing. Key Principles: The choice of dissociation method is critical. A detergent-based lysis is preferred over enzymatic dissociation for solid tumors to preserve nuclear integrity and data quality [8].

Detailed Methodology (Protocol A for Solid Tumors):

- Sample Collection: Obtain fresh tumor tissue from surgery and mince it finely in a KREBS-ringer bicarbonate (KRB) buffer.

- Washing: Centrifuge the minced tissue and wash the pellet with KRB buffer until the supernatant is clear.

- Detergent-Based Lysis:

- Pellet the washed tissue.

- Resuspend the pellet in 100 µL of chilled Lysis Buffer (from the 10x Genomics nuclei isolation protocol) by pipetting 10 times.

- Incubate on ice for 3 minutes.

- Washing Nuclei:

- Add 1 mL of Wash Buffer and centrifuge at 500g for 5 minutes at 4°C.

- Discard the supernatant and repeat the wash step once.

- Resuspension and Quality Control:

- Resuspend the final pellet in a chilled, diluted Nuclei Buffer.

- Assess nuclei concentration and quality by staining with propidium iodide (PI) and using an automated cell counter.

- Critical Step: Visually inspect the nuclei under a microscope (e.g., Nikon Eclipse 50i) after trypan blue staining to confirm the absence of cytoplasmic debris and intact nuclear morphology [8].

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

Diagram 1: Troubleshooting single-cell epigenomics hurdles.

Diagram 2: Enhanced scATAC-seq workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Advanced Single-Cell Epigenomics

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Hyperactive Tn5 Transposase | Fragments DNA and integrates adapters into open chromatin regions. | In-house loading and concentration optimization (e.g., Tn5-H100) can significantly boost sensitivity over some commercial versions [6]. |

| Phosphorylated Adapters | Oligonucleotides for Tn5 loading that are phosphorylated at the 5' end. | Essential for specific multiomic workflows (e.g., scMultiome-ATAC) that combine scATAC-seq with scRNA-seq from the same cell [6]. |

| Protein A-Tagged Tn5 | Tn5 fused to Protein A, enabling targeting to antibody-bound chromatin epitopes. | Used in single-cell CUT&Tag (scC&T-seq) workflows to map histone modifications (e.g., H3K27me3) alongside gene expression [6]. |

| Detergent-Based Lysis Buffer | Lyses cell membranes while leaving nuclei intact. | Critical for high-quality nuclei isolation from solid tissues for snATAC+snRNA assays; superior to collagenase-based dissociation for data quality [8]. |

| SnapATAC2 Software | A Python package for comprehensive single-cell omics data analysis. | Implements a fast, matrix-free spectral embedding algorithm for scalable dimensionality reduction, crucial for large datasets [5]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting ATAC-seq and scATAC-seq Data

Common Issue: Strange Fragment Size Distribution A proper ATAC-seq fragment size distribution should show clear peaks at approximately 50 bp (nucleosome-free regions), 200 bp (mononucleosome), and 400 bp (dinucleosome). The absence of this pattern may indicate over-tagmentation or DNA degradation [1].

Solution:

- Optimize transposition time and temperature according to your cell type.

- Use fresh cells and ensure they are not over-digested. Over-tagmentation can mask nucleosomal features while potentially preserving promoter signal [1].

Common Issue: Low TSS Enrichment Score A Transcription Start Site (TSS) enrichment score below 6 is a warning sign of poor signal-to-noise ratio or uneven fragmentation [1].

Solution:

- This can be cell-type dependent. Compare against positive controls from the same or similar cell type.

- Check for technical issues during cell lysis and nucleus isolation.

Common Issue: Unstable or Inconsistent Peak Calling Standard peak callers like MACS2 assume sharp peaks and may not perform optimally with all data types [1].

Solution:

- For broader nucleosome patterns: Consider using tools like HMMRATAC or Genrich.

- For scATAC-seq data sparsity: Use cluster-wise peak calling instead of merging peaks from all cells. This prevents the loss of cell-type-specific signals that can occur in a "majority vote" approach [1].

- Always remove mitochondrial reads before peak calling to prevent inflation of peaks near chrM-like sequences [1].

Common Issue: Differential Analysis Does Not Match Biological Expectations Discrepancies can arise from how peaks are defined, batch effects, or replicate quality [1].

Solution:

- Ensure high replicate quality and account for batch effects in the experimental design and statistical model.

- Use negative control samples to help normalize data appropriately.

Guide 2: Troubleshooting CUT&Tag and Targeted Enrichment Assays

Common Issue: Sparse or Uneven Signal CUT&Tag data often has low background but can be sparse, making it difficult for peak callers to function correctly [1].

Solution:

- Be cautious of peaks called in regions with only 10–15 reads; these may be false positives.

- Merge replicates before peak calling to increase read depth and signal confidence.

- Visually inspect putative peaks in a genome browser like IGV for validation [1].

Common Issue: Inconsistent Results from Peak Callers Different peak-calling algorithms (e.g., SEACR, MACS2, GoPeaks) can yield different results [1].

Solution:

- For broad histone marks (e.g., H3K27me3, H3K9me3), ensure your peak caller is used in the appropriate mode (e.g.,

-broadflag in MACS2). The statistical model for broad regions is different from that for sharp peaks [1]. - Manually tune parameters based on your expected signal type.

Common Issue: Weak Signal in Double-IP Methods (reChIP, Co-ChIP) These methods have low yields, which can lead to weak signals [1].

Solution:

- Manual validation of results is crucial. Use IGV or the UCSC Genome Browser for visual confirmation of called peaks [1].

Guide 3: Addressing Cell-Type Heterogeneity in Epigenetic Analysis

Common Problem: Bulk Measurements Mask Cell-Type-Specific Signals Epigenetic measurements from bulk tissue represent an average across all constituent cell types. This can confound analysis, as changes in cell-type composition can be misinterpreted as disease-associated epigenetic changes [9].

Solution: Computational Deconvolution

- Use computational tools to estimate cell-type fractions in your bulk samples.

- Perform differential analysis both before and after adjusting for these estimated cell-type fractions. This reveals which epigenetic alterations are independent of cellular composition changes [9].

Table 1: Impact of Cell-Type Heterogeneity (CTH) Adjustment on Analysis

| Analysis Type | Key Risk Without CTH Adjustment | Benefit of CTH Adjustment |

|---|---|---|

| Differential Methylation | Inflated false positives due to shifting cell-type proportions between conditions (e.g., disease vs. control) [9]. | Identifies true, cell-type-intrinsic epigenetic changes, leading to more precise biomarkers and biological insights [9]. |

| Biomarker Discovery | Biomarkers may reflect cell composition changes rather than molecular pathology, limiting clinical utility and reproducibility [9]. | Improves biomarker specificity and accuracy, which is critical for applications like cancer diagnosis from cell-free DNA [9]. |

| Gene Set Enrichment | Results are swamped by functions related to the most variable cell types, obscuring relevant pathways [9]. | Provides a more informative and unbiased picture of the biological processes and pathways involved. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is differential variability (DV) analysis, and how does it complement standard differential expression (DE) in single-cell studies?

Standard DE analysis identifies genes with changed average expression between conditions. In contrast, DV analysis identifies genes with changed variability in their expression across cells from different conditions. This is crucial because increased variability in gene expression is often associated with key biological processes like stem cell differentiation, cellular reprogramming, and aging. A DV gene is functionally more active or transcriptionally more engaged in one condition than another, providing a distinct perspective on cellular state transitions independent of mean expression [10].

Q2: My single-cell chromatin data is extremely sparse. What normalization and clustering strategies are recommended?

For sparse single-cell chromatin data (e.g., scATAC-seq), standard methods can fail. It is recommended to use Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) normalization. This method, borrowed from text mining, effectively balances peak-level variability with cell-to-cell differences in sequencing depth. Tools like ArchR and Signac implement this approach. For clustering, methods based on Latent Semantic Indexing (LSI) or Non-negative Matrix Factorization (NMF) are often more effective than those designed for RNA-seq data [1].

Q3: How can I functionally interpret a list of Highly Variable Genes (HVGs) from a homogeneous cell population?

Embrace the "variation-is-function" concept. In a homogeneous population, HVGs are not just technical noise; they are often key players in cell-type-specific biological processes and molecular functions. Interestingly, most HVGs are not highly expressed, whereas highly expressed genes (e.g., housekeeping genes) tend to be less informative about specific cell functions. Therefore, your HVG list likely contains genes central to the specific identity and function of the cell type you are studying [10].

Q4: I am studying a broad histone mark like H3K27me3 with ChIP-seq or CUT&Tag. Why is my peak caller missing known regulated regions?

Many peak callers are optimized for sharp, punctate signals from factors like transcription factors. Broad histone marks require specific settings. For example, when using MACS2, you must use the -broad flag. This not only changes the peak width threshold but also engages a different statistical model suitable for detecting large, diffuse domains of enrichment [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents for Single-Cell Epigenomic Protocols

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Formaldehyde (Methanol-Free) | A reversible crosslinker used in fixed cell and tissue preparation for techniques like CUT&Tag. It is critical to use a fresh stock and avoid over-fixation, which can lead to weaker signals [11]. |

| Digitonin | A detergent used to permeabilize cell membranes in protocols like CUT&Tag and CUT&RUN. It allows antibodies and enzymes (like pA-Tn5) to enter the nucleus. Different cell lines have varying sensitivities, so concentration may need optimization [11]. |

| Concanavalin A Beads | Magnetic beads used in CUT&Tag to immobilize cells, facilitating buffer exchanges and reagent handling throughout the multi-step protocol without centrifugation [11]. |

| pA-Tn5 Transposase | A fusion protein critical for CUT&Tag. Protein A (pA) binds the Fc region of antibodies, targeting the Tn5 transposase to specific genomic loci. Tn5 then simultaneously cuts DNA and inserts sequencing adapters [11]. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktail | Added to wash and lysis buffers to prevent protein degradation during sample preparation, preserving the integrity of epigenetic marks and target proteins [11]. |

| Spermidine | A polycation that is thought to stabilize chromatin and enzymatic reactions. It is a standard component in wash buffers for CUT&Tag and related assays [11]. |

| Glycine Solution | Used to quench formaldehyde crosslinking reactions by reacting with and neutralizing excess formaldehyde, thereby stopping the fixation process [11]. |

Experimental Workflows & Signaling Pathways

Diagram 1: spline-DV Analysis Workflow

Diagram 2: Cell-Type Heterogeneity Adjustment Logic

Diagram 3: ATAC-seq Fragment Size QC

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the minimum hardware requirements for running a standard scATAC-seq analysis pipeline? The computational resources required depend heavily on the number of cells being analyzed. For data pre-processing with tools like Cell Ranger ATAC, a minimum of 64 GB of RAM is recommended, though 160 GB enhances efficiency. A 64-bit Linux operating system (e.g., CentOS/RedHat 7.0 or Ubuntu 14.04) is required. For downstream analysis of fewer than 100,000 cells using ArchR, a minimum of 8 CPU cores, 32 GB of RAM, and 100 GB of disk space is needed, with the process taking approximately 1 hour. Analyzing one million cells with the same resources can take about 8 hours [12].

Q2: How can I reduce doublets and off-target signals in single-cell histone modification profiling? In methods like scMTR-seq, a key optimization is the addition of IgG blocking antibodies to the post-assembled proteinA-antibody mixture. This significantly reduces off-target signals, where reads from one histone modification (e.g., H3K27ac) aberrantly overlap with the signal of another (e.g., H3K27me3). Furthermore, performing reverse transcription (RT) of RNA after DNA tagmentation, rather than before, helps minimize background noise in the chromatin data [13].

Q3: What are the key quality control (QC) metrics for scATAC-seq data, and what are their recommended thresholds? Several QC metrics should be evaluated for each cell. The following table summarizes the key metrics and typical thresholds used for filtering low-quality cells in scATAC-seq data [14] [15]:

Table: Key Quality Control Metrics for scATAC-seq Data

| QC Metric | Description | Recommended Threshold |

|---|---|---|

| Fraction of Reads in Peaks (FRiP) | The percentage of all fragments that fall within peak regions. Indicates signal-to-noise ratio. | >15% [14] |

| Unique Fragments per Cell | The number of distinct, non-duplicated sequenced fragments per cell. Measures library complexity. | >3,000 [14] |

| TSS Enrichment Score | Measures the enrichment of fragments at transcription start sites. Higher scores indicate better data quality. | >2 [14] |

| Nucleosome Signal | The ratio of fragments spanning nucleosome-sized lengths (>147 bp) to subnucleosomal fragments. | <4 [14] |

| Blacklist Ratio | The fraction of fragments falling within genomic "blacklist" regions known for artifacts. | <0.05 [14] |

Q4: Which tools are available for the comprehensive analysis of single-cell chromatin accessibility data? scATAC-pro is a comprehensive, open-source workbench that can process data from various scATAC-seq protocols. It handles the entire workflow, from raw FASTQ files through downstream analysis, including read mapping, peak calling, cell calling, dimensionality reduction, clustering, and differential accessibility analysis. It provides flexible method choices (e.g., BWA or Bowtie2 for alignment; MACS2 or GEM for peak calling) and generates detailed quality assessment reports [15]. Other widely used tools for downstream analysis include ArchR and Signac (an extension of the Seurat framework) [12] [16] [14].

Q5: How does the novel IT-scATAC-seq method improve upon existing technologies? IT-scATAC-seq addresses limitations in throughput, cost, and equipment requirements of existing methods. It is a semi-automated, plate-based method that uses a three-round barcoding strategy with in-house assembled indexed Tn5 transposomes. Key improvements include:

- Cost-Effectiveness: Reduces the per-cell cost to approximately $0.01.

- Throughput: Can prepare libraries for up to 10,000 cells in a single day.

- Data Quality: Achieves high library complexity and a high fraction of reads in peaks (FRiP score over 65%), which is comparable or superior to other methods like 10X Chromium or sci-ATAC-seq [17].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Library Complexity or Cell Recovery in scATAC-seq

Problem: The number of unique fragments per cell is low, or a high percentage of input cells are lost after quality control.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Poor nuclear integrity or preparation.

- Solution: Optimize the nuclei isolation protocol. Use fluorescence-activated nuclei sorting (FANS) to select for intact nuclei and remove debris [17].

- Cause: Over- or under-digestion during tagmentation.

- Solution: Titrate the amount of Tn5 enzyme used and the duration of the tagmentation reaction. Using pre-assembled indexed Tn5 complexes can improve consistency [17].

- Cause: Overly stringent filtering during data processing.

- Solution: Re-visit the parameters for cell calling. While a common filter is to keep cells with >5,000 unique fragments and a FRiP score >50%, these thresholds may need adjustment based on your specific experiment and protocol [15].

Issue 2: High Background Noise in Single-Cell Multi-Histone Modification Profiling

Problem: Significant off-target signal is observed, where reads assigned to one histone modification show enrichment patterns typical of another.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Non-specific binding of antibody-Tn5 complexes.

- Solution: Incorporate an IgG blocking step during the assembly of antibody and proteinA-Tn5 adapter complexes. This helps neutralize excess proteinA and reduces mis-targeting [13].

- Cause: Suboptimal order of enzymatic steps.

- Solution: Ensure that reverse transcription (RT) for transcriptome capture is performed after DNA tagmentation. Performing RT first can be detrimental to the quality of the chromatin data [13].

- Cause: Low complexity of indexed libraries.

- Solution: Implement an adapter-switching strategy. Using a mosaic end B (MEB) adapter for initial tagmentation followed by the addition of a mosaic end A (MEA) adapter to all fragments can improve the signal-to-background ratio and increase library complexity [13].

Issue 3: Failure to Integrate scATAC-seq and scRNA-seq Data

Problem: Inability to harmonize datasets from different modalities to infer cell types or link regulatory elements to genes.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Incorrect normalization or feature selection.

- Cause: Batch effects or technical differences between the two assays.

- Solution: Use integration tools designed for multi-omics data. The Signac package (which extends Seurat) provides functions to find a shared latent space between ATAC and RNA datasets, enabling the transfer of cell-type labels from a reference scRNA-seq dataset to the scATAC-seq cells [14].

- Cause: Lack of common anchors between datasets.

- Solution: Use gene activity scores derived from scATAC-seq data (by quantifying accessibility near gene promoters) as a common feature space to anchor with the gene expression matrix from scRNA-seq data [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table: Key Reagents for Single-Cell Epigenomics Protocols

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Indexed Tn5 Transposase | Simultaneously fragments and tags accessible genomic DNA with sequencing adapters. | scATAC-seq; IT-scATAC-seq [17] |

| Barcoded ProteinA-Tn5 Adapters | Pre-assembled complexes that enable antibody-specific targeting and tagging of histone modifications. | scMTR-seq for profiling multiple histone marks [13] |

| Barcoded Poly(dT) Primers | Capture polyadenylated mRNA within individual nuclei for transcriptome sequencing. | Multi-omics protocols like scMTR-seq [13] |

| Histone Modification-Specific Antibodies | Bind to specific histone PTMs (e.g., H3K27ac, H3K4me3) to target tagmentation or pull-down. | scCUT&Tag; scMTR-seq [13] |

| IgG Blocking Antibodies | Reduce off-target tagmentation by binding to excess ProteinA. | Improving specificity in scMTR-seq [13] |

| Fluorescence-Activated Nuclei Sorting (FANS) | Isolates high-quality, intact nuclei from debris and can be used for plate-based distribution. | IT-scATAC-seq; nuclei preparation [18] [17] |

Experimental Workflow Diagrams

Single-Cell Multi-Omics Integration Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a standard computational workflow for integrating scATAC-seq and scRNA-seq data to infer cell types and regulatory networks, based on analyses performed with Signac and Seurat [14].

scMTR-seq for Combined Histone and Transcriptome Profiling

This diagram outlines the key wet-lab steps in the scMTR-seq protocol, which allows for the simultaneous profiling of multiple histone modifications and the transcriptome in the same single cell [13].

Advanced Protocols and Multi-Omic Integration for Enhanced Cellular Profiling

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: When should I use single-nuclei sequencing instead of single-cell sequencing? Single-nuclei RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) is preferred when working with difficult-to-dissociate tissues (e.g., brain, heart, adipose), frozen or biobanked specimens, or when performing multi-omics assays like scATAC-seq. Nuclei are more resilient than whole cells and provide access to nascent RNA, making them ideal for archived samples or tissues that cannot be freshly processed [19] [20] [21].

FAQ 2: What are the critical parameters to optimize during cell lysis for nuclei isolation? The key parameters are lysis buffer composition (detergent type and concentration), mechanical agitation method (e.g., Dounce homogenizer, number of strokes), and lysis time. Optimization is crucial as each sample type behaves differently. The goal is to permeabilize the plasma membrane while leaving the nuclear envelope intact. It is recommended to check lysis status every 1-2 minutes during protocol optimization [19] [21].

FAQ 3: How can I reduce ambient RNA contamination in my nuclei preparation? Ambient RNA from lysed cells can be minimized by using purification steps such as fluorescence-activated nuclei sorting (FACS) or iodixanol density gradient centrifugation. These techniques help remove cellular debris and select for intact nuclei, significantly reducing background noise in downstream sequencing [19] [20].

FAQ 4: My nuclei are clumping. How can I prevent this? Nuclei clumping can be reduced by including 0.5–1% BSA in all wash and resuspension buffers. Additionally, using RNase inhibitors and avoiding over-lysis during homogenization helps maintain nuclear integrity and prevents aggregation [21].

FAQ 5: What is an acceptable nuclei integrity and yield for a successful snRNA-seq experiment? High-quality preparations should contain ≥90% single, round nuclei with sharp borders under a microscope. For yield, protocols optimized for low-input cryopreserved tissues (e.g., 15 mg) can reliably profile 1,500–7,500 nuclei per tissue, which is sufficient for revealing cellular heterogeneity [19] [21].

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Common Nuclei Isolation Problems and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low nuclei yield | Incomplete tissue dissociation, insufficient lysis | Optimize homogenization: adjust number of Dounce strokes or pestle type (loose vs. tight) [19]. |

| High debris contamination | Over-lysed tissue, inefficient purification | Add a purification step: use iodixanol density gradient [19] or MACS strainers [19]. |

| Poor RNA quality/High ambient RNA | RNase contamination, excessive mechanical force | Treat surfaces with RNaseZap [21]; use Protector RNase inhibitor in buffers [19]. |

| Nuclei clumping | Lack of detergent or BSA, over-concentration | Include 0.5-1% BSA in resuspension buffers [21]. |

| Low cell type diversity in data | Protocol-induced bias, loss of fragile nuclei | Compare isolation methods; sucrose gradient or machine-assisted platforms better preserve fragile populations [20]. |

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Nuclei Isolation Method Performance

This table summarizes data from a systematic comparison of three nuclei isolation methods using mouse brain cortex tissue [20].

| Method | Total Nuclei Yield (per ~30 mg tissue) | Nuclei Integrity | Key Cell Types Best Captured | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sucrose Gradient Centrifugation | ~2 million | 85% | Astrocytes (13.9%) | Well-defined nuclei, minimal debris, cost-effective. |

| Spin Column-Based | 25% fewer than above | 35% | General populations | Faster processing, no ultracentrifugation. |

| Machine-Assisted Platform | ~2 million | ~100% | Microglia (5.6%), Oligodendrocytes (15.9%) | Automated, high purity, negligible debris, maximal integrity. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Versatile Nuclei Isolation from Low-Input Cryopreserved Tissues

This protocol is designed for low-input (15 mg) cryopreserved human tissues and has been validated on cancer tissues from brain, bladder, lung, and prostate [19].

Reagents and Materials:

- Lysis Buffer: 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl₂.6H₂O, 0.05% NP-40

- Nuclei Washing Buffer: 0.5X PBS, 5% BSA, 0.25% Glycerol, 40 units/mL Protector RNase Inhibitor

- Iodixanol (Optiprep)

- Dounce homogenizer with loose (A) and tight (B) pestles

- 30 µm MACS strainers

Methodology:

- Homogenization: Minced cryopreserved tissue is transferred to a pre-cooled Dounce homogenizer containing 3 mL of ice-cold lysis buffer. The number of strokes and pestle type (A or B) are optimized for each tissue type.

- Lysis and Filtration: After homogenization, add 2 mL more lysis buffer, incubate on ice for 5 min, and stop the reaction with 5 mL of ice-cold nuclei washing buffer. Filter the suspension through a 30 µm strainer.

- Purification: Centrifuge the filtrate at 1000 g for 10 min at 4°C. Resuspend the pellet in 1 mL of washing buffer, then add 1 mL of 50% iodixanol. Gently layer this suspension on top of a 2 mL cushion of 29% iodixanol. Centrifuge and resuspend the purified nuclei pellet in 300 µL of washing buffer.

- Nuclei Sorting (Optional): For highest purity, stain nuclei with 7-AAD and sort using a flow sorter (e.g., BD FACSAria Fusion) to collect fluorescent-positive, correctly sized nuclei.

Protocol 2: Comparative Analysis of Three Isolation Methods for Brain Tissue

This protocol compares three mechanistically distinct strategies for isolating nuclei from complex brain tissue [20].

Methods Compared:

- Sucrose Gradient Centrifugation: Manual homogenization followed by sucrose gradient centrifugation.

- Spin Column-Based Method: A commercial spin column-based method for nuclei isolation.

- Machine-Assisted Platform: An automated, machine-assisted platform for consistent processing.

Key Findings and Best Practices:

- Yield and Integrity: The sucrose gradient and machine-assisted methods provided the highest yields (~2 million nuclei from ~30 mg cortex) and superior nuclei integrity (85% and ~100%, respectively). The column-based method yielded 25% fewer nuclei with only 35% integrity.

- Cell Type Bias: The isolation technique influenced the proportions of captured cell types. The centrifugation-based method captured the most astrocytes, while the machine-assisted method best captured microglia and oligodendrocytes.

- Recommendation: The machine-assisted platform offers the best combination of yield, purity, and reproducibility, while the sucrose gradient method is a reliable, cost-effective manual alternative.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Dounce Homogenizer | Mechanical tissue disruption with controlled clearance. | Pestle A (loose): 0.0025-0.0055 in; Pestle B (tight): 0.0005-0.0025 in [19]. |

| Non-ionic Detergent | Permeabilizes the plasma membrane without disrupting the nuclear envelope. | NP-40 (0.05%) [19] or Triton X-100 [21]. |

| RNase Inhibitor | Protects RNA integrity during the isolation process. | 40 units/mL Protector RNase Inhibitor [19]. |

| Iodixanol (Optiprep) | Forms a density gradient for purification of nuclei, removing debris. | 29% (wt/vol) solution for cushion [19]. |

| Fluorescent Nuclear Stain | Enables viability assessment and sorting of intact nuclei. | 7-AAD [19], Propidium Iodide (PI), or Acridine Orange/PI (AOPI) [21]. |

| BSA | Reduces nuclei clumping by preventing non-specific adhesion. | 0.5-1% in wash and resuspension buffers [21]. |

Workflow Visualization

This section compares two leading platforms for simultaneous single-cell multi-omics profiling, helping you select the appropriate technology for your experimental needs.

Technology Comparison

Table 1: Platform Comparison: SHARE-seq vs. snATAC+snRNA

| Feature | SHARE-seq | snATAC+snRNA (e.g., SUM-seq, 10x Multiome) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Plate-based, three rounds of hybridization barcoding [22] [23] | Droplet-based microfluidics with combinatorial indexing [24] |

| Typical Cell Throughput | Up to 100,000 cells with 2-plate barcode system [22] | Up to millions of cells per experiment [24] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | High (hundreds of samples via barcoding) [22] | High (hundreds of samples) [24] |

| Key Strength | Cost-effective for high sample multiplexing; identifies peak-gene associations and DORCs [23] | Ultra-high-throughput; ideal for massive cell numbers and time-course experiments [24] |

| Reported Data Quality | ~2,545 RNA UMIs; ~8,252 unique ATAC fragments per cell [23] | ~407 RNA UMIs; ~11,900 unique ATAC fragments per cell (varies by protocol) [24] |

| Sample Compatibility | Fixed cells or nuclei [22] [23] | Fixed or frozen nuclei, ideal for prolonged sample collection [24] |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Which platform should I choose for a complex time-course experiment with over 50 samples? For complex experimental designs involving many samples (e.g., time courses, drug screens), SUM-seq or similar high-throughput snATAC+snRNA methods are generally preferred. Their combinatorial indexing approach is designed to profile hundreds of samples in a single experiment, is cost-effective at this scale, and supports fixed/frozen samples for asynchronous collection [24].

Q2: How can I improve cell type identification, especially for rare populations like podocytes? Using nuclei (snRNA-seq) instead of whole cells (scRNA-seq) can significantly improve the recovery of fragile or structurally embedded cell types like podocytes. Strong dissociation protocols for whole cells can damage these cells, whereas nuclei isolation more effectively preserves them for analysis [25].

Q3: My multiomic data shows discordance between chromatin accessibility and gene expression for a cell population. Is this a technical error? Not necessarily. Biological chromatin lineage priming is a recognized phenomenon where chromatin becomes accessible at key regulatory regions before the associated gene is highly expressed, potentially foreshadowing cell fate decisions. SHARE-seq was instrumental in identifying these "Domains of Regulatory Chromatin" (DORCs) [23]. This apparent discordance can be a source of biological insight.

Experimental Protocol Optimization

This section addresses critical wet-lab challenges, from sample preparation to library construction.

Key Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Their Functions

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Glyoxal | Fixation agent | Used in SUM-seq; allows sample cryopreservation after fixation, enabling asynchronous sampling [24]. |

| NP-40 Detergent | Cell membrane lysis for nuclei isolation | Superior to collagenase-based dissociation for solid tumors (e.g., ovarian cancer), yielding better sequencing data [8]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Molecular crowding agent in RT reaction | In SUM-seq, adding PEG increased RNA UMIs and genes detected per cell by ~2.5-fold and ~2-fold, respectively [24]. |

| Blocking Oligonucleotides | Prevents barcode hopping | Added in excess during droplet barcoding to mitigate cross-talk between nuclei in multinucleated droplets [24]. |

| STE Buffer (10mM Tris, 50mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA) | Oligo annealing buffer | Critical for preparing SHARE-seq hybridization plates; the slow ramp during annealing is essential for protocol success [22]. |

| Tn5 Transposase | Fragments and tags accessible genomic DNA | Loaded with barcoded oligos in SUM-seq for initial ATAC indexing [24]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q4: How can I minimize "barcode hopping" or "collision" in my dataset? Barcode hopping, where reads are misassigned between cells, primarily affects the ATAC modality and occurs in multinucleated droplets [24]. To mitigate this:

- Reduce linear amplification cycles during droplet barcoding (e.g., from 12 to 4 cycles) [24].

- Add a blocking oligonucleotide in excess during the barcoding step [24].

- For SHARE-seq, ensure you do not create cellular sub-pools larger than 25,000 cells when using a single 96-well barcode plate to keep the collision rate below ~5% [22].

Q5: My RNA quality is poor in SHARE-seq. What could be the issue? RNA degradation is a common challenge in the "lossy" SHARE-seq protocol. To maintain RNA quality:

- Aliquot key reagents like DTT, BSA, and buffer stocks to avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles and potential RNase contamination [22].

- If RNA quality is poor, discard your current in-use aliquots and use fresh, RNase-free reagents [22].

Q6: What is the best nuclei isolation method for solid tumor samples? For solid tumors like ovarian cancer, a detergent-based lysis method (e.g., using NP-40) has been benchmarked and shown to yield superior sequencing results compared to enzymatic dissociation (e.g., collagenase). This method provides better data quality, which directly impacts the ability to identify distinct cell types [8].

Data Analysis and Computational Integration

This section provides guidance on processing, integrating, and interpreting multiomic data.

Data Analysis Logic

Frequently Asked Questions

Q7: What is the best computational method to integrate my own scRNA-seq and snATAC-seq data with a public multiome dataset? A comprehensive benchmark study found that Seurat v4 is the best currently available platform for integrating scRNA-seq, snATAC-seq, and multiome data, even in the presence of complex batch effects. Its Weighted Nearest Neighbors (WNN) analysis effectively learns a joint representation from the multiome data to guide the integration of single-modality datasets [26].

Q8: When integrating single-modality data, is the number of multiome cells or sequencing depth more important? Benchmarking results indicate that the number of cells in the multiome dataset is more important than sequencing depth for achieving accurate cell type annotation during integration. An adequate number of multiome nuclei is crucial for reliable annotation [26].

Q9: My data shows chromatin accessibility at a gene's regulatory elements but low gene expression. Does this indicate a problem? Not necessarily. This can reflect a biologically meaningful primed chromatin state. SHARE-seq analysis in mouse skin revealed that during lineage commitment, chromatin accessibility at key Domains of Regulatory Chromatin (DORCs) often precedes gene expression. This "chromatin potential" can be quantified and may predict future cell fate outcomes [23].

Q10: How can I link non-coding genetic variants to target genes using multiomic data? Simultaneous snATAC-seq and snRNA-seq profiling is powerful for bridging TF regulatory networks to immune disease genetic variants. The paired data allows you to:

- Identify accessible chromatin regions that contain the genetic variant (via snATAC-seq).

- Correlate the accessibility of that region with the expression of potential target genes in the same cell (via snRNA-seq).

- This direct linkage helps interpret the function of non-coding disease-associated variants [24].

Single-cell Methylome and Transcriptome sequencing (scM&T-seq) is a pioneering multi-omics protocol that enables the parallel genome-wide profiling of DNA methylation and gene expression within the same single cell [27]. This revolutionary method builds upon the principles of G&T-seq (Genome and Transcriptome sequencing) by incorporating bisulfite conversion of genomic DNA, thereby allowing researchers to discover associations between transcriptional and epigenetic variation at single-cell resolution [27] [28]. The ability to concurrently capture these two fundamental layers of molecular information from individual cells provides unprecedented opportunities to dissect the complex regulatory relationships governing cellular heterogeneity in development, disease, and normal physiological processes.

The technological innovation of scM&T-seq addresses a critical gap in single-cell genomics. While previous methods could profile either the transcriptome or methylome from individual cells, understanding how these layers interact within the same cellular context remained experimentally challenging. By physically separating polyadenylated RNA from genomic DNA immediately after cell lysis, scM&T-seq enables the application of optimized, dedicated protocols for each molecular type: Smart-seq2 for transcriptome analysis and scBS-seq (single-cell bisulfite sequencing) for methylome analysis [27] [28]. This strategic separation is particularly crucial as it allows bisulfite conversion of DNA without compromising RNA integrity, thereby preserving transcriptome information while enabling methylation assessment.

For researchers investigating heterogeneous cell populations—such as embryonic stem cells, tumor ecosystems, or developing tissues—scM&T-seq provides a powerful tool to move beyond correlative studies conducted across different cells toward causal mechanistic insights within the same cell. The method has demonstrated particular utility in stem cell biology, where it has revealed novel associations between heterogeneously methylated distal regulatory elements and transcription of key pluripotency genes [27]. As the field of single-cell multi-omics continues to evolve, scM&T-seq stands as a foundational methodology that enables truly integrated analysis of epigenetic and transcriptional regulation.

Experimental Workflow

The scM&T-seq protocol involves a carefully orchestrated sequence of steps designed to maximize the quality and completeness of both methylome and transcriptome data from individual cells. The entire process, from cell preparation to sequencing, typically requires 3-5 days, with critical checkpoints for quality assessment at multiple stages. The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow:

Key Molecular Separation Principle

The foundational innovation of scM&T-seq lies in the physical separation of RNA and DNA molecules after cell lysis, which enables specialized processing for each molecular type. The following diagram details this crucial separation mechanism:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of scM&T-seq requires carefully selected reagents and materials optimized for single-cell sensitivity and compatibility with downstream applications. The table below details the essential components of the scM&T-seq workflow:

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for scM&T-seq

| Reagent Category | Specific Product/Type | Function in Workflow | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Isolation | Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) | High-throughput isolation of single cells with viability selection | Maintain >99% cell viability; use DNA content staining (Hoechst 33342) to select G0/G1 phase cells [27] |

| Cell Lysis | RLT Plus Buffer (Qiagen) with 1 U/μl SUPERase-In | Complete cellular lysis while preserving RNA integrity | Freshly prepare lysis buffer; include RNase inhibitors to prevent RNA degradation [27] |

| Nucleic Acid Separation | Streptavidin Magnetic Beads with oligo(dT) primers | Physical separation of mRNA from genomic DNA via poly(A) tail capture | Optimize bead-to-cell ratio to maximize mRNA capture efficiency [28] [29] |

| RNA Processing | Smart-seq2 Reagents | Template-switching reverse transcription and cDNA amplification | Use UMI incorporation to control for amplification bias; enables full-length transcript coverage [27] [30] |

| DNA Processing | scBS-seq Reagents | Bisulfite conversion and post-bisulfite adapter tagging | Achieve >95% bisulfite conversion efficiency; optimize cycles to minimize DNA fragmentation [27] [31] |

| Library Preparation | Illumina-Compatible Adapters | Dual-indexed library construction for both RNA and DNA | Use unique dual indexes to prevent index hopping in multiplexed sequencing [27] |

| Quality Control | Bioanalyzer/TapeStation | Assessment of library quality and fragment size distribution | RNA libraries: 300-500bp peak; DNA libraries: broader distribution (200-600bp) [27] |

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

Table 2: scM&T-seq Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low RNA Mapping Efficiency | RNA degradation during cell sorting or lysis | Include RNase inhibitors in all solutions; minimize sorting time | Quality check RNA integrity number (RIN) >8.5 from bulk samples before single-cell processing [27] |

| High Duplication Rates in Methylome Data | Insufficient starting material leading to over-amplification | Increase PCR cycles gradually; optimize amplification | Sequence libraries to higher depth; use unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) where possible [27] |

| Low Bisulfite Conversion Efficiency | Incomplete bisulfite reaction; insufficient desulfonation | Freshly prepare bisulfite solution; optimize incubation time and temperature | Include unmethylated lambda DNA spike-in controls to monitor conversion efficiency (>95%) [27] [31] |

| Genomic DNA Contamination in RNA Libraries | Incomplete separation of DNA and RNA | Increase bead washing steps; implement DNase treatment | Verify separation efficiency using control cells with pre-quantified RNA/DNA ratios [28] |

| Low CpG Coverage in Methylome | Inefficient tagmentation or PBAT | Optimize tagmentation time and temperature; titrate Tn5 enzyme | Increase sequencing depth to 10-15M reads per cell; use targeted approaches for specific genomic regions [27] [32] |

| Cell-to-Cell Variation in Data Quality | Inconsistent cell lysis or technical variability | Standardize lysis conditions; implement rigorous QC thresholds | Use automated liquid handling systems to reduce technical variation between cells [27] [33] |

Quality Control Parameters and Benchmarks

Establishing rigorous quality control metrics is essential for generating publication-quality scM&T-seq data. The following table provides benchmark values for key QC parameters:

Table 3: Quality Control Metrics for scM&T-seq Data

| QC Parameter | Minimum Threshold | Optimal Performance | Assessment Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA-Seq Mapping Efficiency | >60% | >80% | Alignment to reference transcriptome [27] |

| Transcripts Detected per Cell | >4,000 genes | >8,000 genes | >1 TPM threshold [27] |

| Methylome Mapping Efficiency | >7% | >15% | Alignment to reference genome post-bisulfite conversion [27] |

| Bisulfite Conversion Efficiency | >95% | >98% | Non-CpG methylation or spike-in controls [27] [31] |

| CpG Coverage per Cell | >1 million sites | >3 million sites | Number of CpGs with ≥5x coverage [27] |

| Duplicate Rate in Methylome | <40% | <25% | PCR duplicate analysis [27] |

| Library Complexity (RNA) | >2,000 genes/cell | >5,000 genes/cell | Saturation curve analysis [27] [33] |

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the key advantages of scM&T-seq over separate single-cell methylome and transcriptome profiling?

scM&T-seq enables the direct correlation of DNA methylation and gene expression within the same individual cell, eliminating the need for computational integration of datasets from different cells. This direct pairing reveals gene-specific regulatory relationships that would be obscured when profiling different cells [27] [33]. For example, the method has been used to identify novel associations between heterogeneously methylated distal regulatory elements and transcription of key pluripotency genes like Esrrb in embryonic stem cells [27]. The physical separation of DNA and RNA before processing allows optimized library preparation for each molecular type without cross-contamination or protocol compromise [28].

What are the main limitations of scM&T-seq and how can they be addressed?

The primary limitations include: (1) Inability to distinguish between 5-methylcytosine (5mC) and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) due to bisulfite treatment [28]; (2) Lower coverage compared to standalone methods, with typical methylome coverage of ~3-4 million CpGs per cell versus >10 million in scBS-seq [27]; (3) Higher cost and complexity compared to single-omics approaches [29]. These limitations can be mitigated by using oxidative bisulfite sequencing for 5hmC detection, increasing sequencing depth to improve coverage, and employing automation to reduce technical variability [31].

How much sequencing depth is recommended for each molecular layer in scM&T-seq?

For the transcriptome component, aim for 2-5 million reads per cell to detect 4,000-8,000 genes [27]. For the methylome, deeper sequencing of 10-15 million reads per cell is recommended to achieve coverage of 3-5 million CpG sites [27]. These requirements may vary based on your biological system and research questions. For studies focusing on specific genomic regions, you may consider targeted approaches to reduce sequencing costs while maintaining adequate coverage for key regulatory elements [31].

Can scM&T-seq be applied to clinical samples with limited cell numbers?

Yes, scM&T-seq is particularly valuable for clinical samples with limited cellularity, such as circulating tumor cells, rare cell populations, or precious patient biopsies [31] [29]. The method has been successfully applied to in vitro fertilization contexts where material is severely limited [27]. For optimal results with clinical samples, ensure rapid processing after collection, use cell viability markers during sorting, and consider implementing whole-genome amplification for the DNA fraction if copy number variation analysis is also desired [31].

What computational methods are available for analyzing scM&T-seq data?

Several computational approaches have been developed specifically for scM&T-seq data analysis. These include: (1) MATCHER for manifold alignment to reveal correspondence between transcriptome and epigenome dynamics [34]; (2) Correlation analysis to identify associations between DNA methylation levels and gene expression [29] [33]; (3) Regression models that predict splicing variation based on DNA methylation profiles [33]. For integrative analysis, tools like MOFA (Multi-Omics Factor Analysis) and LIGER can identify shared sources of variation across the transcriptomic and epigenetic layers [29].

How does scM&T-seq compare to more recent multi-omics technologies like scNMT-seq?

scM&T-seq profiles two molecular layers (DNA methylation and transcriptome), while scNMT-seq adds a third dimension by incorporating chromatin accessibility through GpC methyltransferase treatment [32]. The choice between methods depends on your research question: scM&T-seq is ideal for focused investigation of methylation-expression relationships, while scNMT-seq provides a more comprehensive epigenetic profile but with increased complexity and cost [32] [29]. scNMT-seq also requires filtering out C-C-G and G-C-G positions (affecting ~48% of CpGs), which reduces genome-wide cytosine coverage compared to scM&T-seq [32].

Single-cell epigenomics has emerged as a transformative technology for deciphering the complex regulatory mechanisms underlying disease pathogenesis and progression. By enabling the analysis of epigenetic modifications—including DNA methylation, chromatin accessibility, and histone modifications—at individual cell resolution, this approach reveals cellular heterogeneity that was previously obscured in bulk tissue analyses [35]. The clinical translation of these technologies is accelerating, with applications now spanning cancer diagnostics, neurodegenerative disease monitoring, and the development of epigenetic therapeutics [36]. This technical support center provides essential guidance for researchers navigating the transition from foundational research to clinically applicable single-cell epigenomic protocols, with an emphasis on improving resolution, accuracy, and reproducibility.

Foundational Concepts and Clinical Relevance

Key Epigenetic Modifications and Their Clinical Significance

Epigenetic modifications represent reversible molecular mechanisms that regulate gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence. These modifications provide critical insights into disease mechanisms and present promising targets for therapeutic intervention [35]. The most clinically relevant epigenetic marks include:

- DNA methylation: The addition of methyl groups to cytosine bases, primarily in CpG islands, typically leading to gene silencing. Aberrant DNA methylation patterns serve as biomarkers for various cancers and developmental disorders [35].

- Histone modifications: Post-translational modifications (e.g., acetylation, methylation) to histone proteins that alter chromatin structure and gene accessibility. Mutations in histone-modifying enzymes are frequently observed in cancers [36].

- Chromatin accessibility: The physical accessibility of DNA regions for transcription, which reflects the integrated activity of multiple epigenetic mechanisms and provides insights into cellular states in health and disease [36].

Analytical Techniques for Clinical Single-Cell Epigenomics

The evolution of single-cell epigenomic technologies has created multiple pathways for clinical investigation, each with distinct strengths and applications:

Single-cell epigenomics technologies enable multiple pathways for clinical investigation, from targeted to comprehensive analyses.

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Sample Preparation and Quality Control

What are the critical factors for successful single-cell epigenomic sample preparation?

Sample quality profoundly impacts data quality in single-cell epigenomics. Three fundamental standards must be met: (1) Cleanliness - single-cell suspensions must be free from debris, cell aggregates, and contaminants; (2) Viability - at least 90% cell viability is recommended for optimal data; and (3) Intactness - cellular or nuclear membranes must remain intact through gentle processing [37]. For nuclei isolation, optimization of lysis time is crucial, as over-lysis can cause nuclear "blebbing" and clumping [37].

How should I preserve tissues for single-cell epigenomics when immediate processing isn't possible?

Preservation strategy depends on your timeline and analytical goals. For delays under 72 hours, store tissue in specialized storage solutions at 4°C. For longer delays, snap-freezing at -196°C enables subsequent nuclei isolation, while cryopreservation at -80°C in cryopreservation media may preserve whole cells and surface proteins [37]. Each method requires validation through pilot studies, as recovery efficiency varies by tissue type.

What are the key differences between sci-ATAC-seq and 10x-ATAC-seq platforms?

The choice between platforms involves trade-offs between flexibility, recovery rates, and data quality. sci-ATAC-seq offers greater experimental flexibility, allowing multiple samples to be mixed in a single run and enabling small-scale pilot experiments. It typically captures approximately 10,000 nuclei per 96-well plate. In contrast, 10x-ATAC-seq provides higher fragment recovery (5,000-12,000 nuclei per sample) and is particularly suitable for cell lines, low-input samples, and tissues with minimal debris [4].

Analytical Challenges and Computational Solutions

How can I address batch effects and technical variability in single-cell epigenomic data?

Technical variability across platforms, protocols, and sequencing batches represents a significant challenge in single-cell epigenomics. Computational harmonization strategies are essential, including the use of foundation models like scGPT pretrained on over 33 million cells, which demonstrate exceptional capability for batch effect correction and cross-dataset integration [38]. Additionally, platforms such as DISCO and CZ CELLxGENE Discover aggregate data from multiple sources and facilitate federated analysis to mitigate batch-related artifacts [38].

What computational approaches are available for integrating multimodal single-cell data?

Multimodal integration represents a frontier in single-cell analysis. Innovative computational frameworks including StabMap enable "mosaic integration" of datasets with non-overlapping features by leveraging shared cellular neighborhoods [38]. Tensor-based fusion methods harmonize transcriptomic, epigenomic, proteomic, and spatial imaging data to delineate multilayered regulatory networks [38]. For clinical applications, PathOmCLIP aligns histology images with spatial transcriptomics via contrastive learning, creating powerful diagnostic interfaces between traditional pathology and molecular profiling [38].

Clinical Translation and Validation

What considerations are unique to clinical application of single-cell epigenomics?

Clinical translation requires special attention to reproducibility, standardization, and analytical validation. Federated computational platforms facilitate decentralized data analysis while maintaining standardized, reproducible workflows [38]. For diagnostic applications, rigorous benchmarking against established clinical standards is essential. Computational frameworks like BioLLM provide universal interfaces for benchmarking multiple foundation models, enabling objective performance assessment across diverse patient cohorts [38].

Quantitative Data Comparison Tables

Comparison of Single-Cell Epigenomic Technologies

Table 1: Technical specifications of major single-cell epigenomic methods

| Method | Target Epigenetic Mark | Throughput | Coverage per Cell | Key Clinical Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sci-ATAC-seq [4] | Chromatin accessibility | ~10,000 nuclei/plate | Variable | Tumor heterogeneity, developmental biology | Lower fragment recovery compared to droplet-based methods |

| 10x-ATAC-seq [4] | Chromatin accessibility | 5,000-12,000 cells/sample | High (5-10x fragments/nucleus) | Cancer diagnostics, immune cell profiling | Requires high sample quality |

| scCUT&Tag [36] | Histone modifications | Medium | ~600 unique fragments/cell | Oncology, epigenetic therapy monitoring | Limited coverage per cell |

| sciCUT&Tag [36] | Histone modifications | High (combinatorial barcoding) | ~1,200 unique fragments/cell | Cancer epigenetics, drug mechanism studies | Protocol complexity |

| scRRBS [35] | DNA methylation | Targeted | Locus-specific | Biomarker discovery, minimal residual disease detection | Limited genomic coverage |

| scWGBS [35] | DNA methylation | Genome-wide | Comprehensive | Comprehensive epigenetic profiling, diagnostic development | Higher cost, computational complexity |

Clinical Validation Studies Using Single-Cell Epigenomics

Table 2: Representative clinical applications of single-cell epigenomic technologies

| Disease Area | Technology Used | Sample Size | Key Findings | Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute Coronary Syndrome [35] | WGBS | 254 DMRs identified | Differential methylation patterns stratified ACS subtypes | Non-invasive diagnostic stratification using ccfDNA |

| Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis [35] | ATAC-Seq | 380 patients | Chromatin accessibility predicts disease progression rate | Prognostic biomarker for clinical trial stratification |

| Crohn's Disease [35] | RRBS | Surgical vs. non-surgical patients | Distinct methylation signatures at different disease stages | Precision classification of disease severity |

| Triple Negative Breast Cancer [35] | Methylation Array | 44 cases | DNA methylation profiles define clinically relevant subgroups | Alternative classification for therapy selection |

| Chondrocyte Senescence [35] | Small RNA Sequencing | 500+ differentially expressed RNAs | Identified sncRNAs associated with osteoarthritis | Novel therapeutic target discovery |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Integrated Single-Cell Multi-Omic Profiling Workflow

Integrated workflow for clinical single-cell epigenomic profiling, highlighting critical quality control checkpoints.

Detailed Methodologies for Key Clinical Applications

Protocol for Single-Cell ATAC-Seq in Cancer Biomarker Discovery

Sample Preparation: Obtain fresh tissue or cryopreserved samples. For solid tumors, perform mechanical dissociation followed by enzymatic digestion to generate single-cell suspensions. Assess viability using fluorescent dyes (e.g., Ethidium Homodimer-1) rather than Trypan Blue to avoid debris confounding [37].

Nuclei Isolation: For frozen tissues, use optimized lysis buffers with precisely timed incubation (typically 5-30 minutes) to preserve nuclear integrity while ensuring complete cellular lysis. Validate nuclear integrity microscopically, assessing for rounded morphology and intact membranes [37].

Library Preparation: Select platform based on sample characteristics and study goals. For 10x-ATAC-seq, input 15,300 cells/nuclei per sample, anticipating recovery of 5,000-12,000 high-quality profiles. For sci-ATAC-seq, partition samples across 96-well plates with appropriate controls [4].

Quality Control Metrics: For ATAC-seq data, evaluate Transcription Start Site (TSS) enrichment, fragment size distribution, and fraction of reads in peaks. Establish sample-specific thresholds based on positive controls [4].

Computational Analysis: Process data using established pipelines (Cell Ranger for 10x data). Employ foundation models like scGPT for batch correction, cell type annotation, and perturbation modeling [38]. Validate findings in independent cohorts using cross-validation approaches.

Protocol for Multi-Omic Integration in Disease Subtyping

Parallel Profiling: Perform scATAC-seq and scRNA-seq on aliquots of the same sample, or utilize commercial multiome solutions that capture both modalities simultaneously.

Data Harmonization: Apply tensor-based integration methods such as TMO-Net's pan-cancer multi-omic pretraining to align datasets while preserving biological signals [38].

Regulatory Network Inference: Utilize scGPT's gene regulatory network inference capabilities to connect chromatin accessibility patterns with gene expression programs [38].

Clinical Validation: Correlate identified subtypes with clinical outcomes, treatment responses, and established pathological markers to establish clinical utility.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key reagents and computational tools for single-cell epigenomic research

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function | Clinical Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Nuclei Isolation Kit [37] | Standardized nuclei extraction from diverse tissues | Ensures reproducibility across patient samples |

| Dead Cell Removal Kits [37] | Enrichment of viable cells/nuclei | Improves data quality from clinical biopsies | |

| Cryopreservation Media [37] | Maintains cell viability during storage | Enables batched processing of clinical samples | |

| Library Preparation | 10x Chromium Controller [4] [37] | Automated partitioning and barcoding | Standardized workflow for clinical studies |

| Tn5 Transposase [36] | Tagmentation of accessible chromatin | Fundamental enzyme for ATAC-seq protocols | |

| Protein A-Tn5 Fusion [36] | Antibody-targeted tagmentation | Enables histone modification profiling (CUT&Tag) | |

| Computational Tools | scGPT [38] | Foundation model for single-cell analysis | Cross-species annotation, perturbation modeling |

| BioLLM [38] | Benchmarking platform for foundation models | Standardized performance assessment | |

| StabMap [38] | Mosaic integration of multimodal data | Harmonizes datasets with non-overlapping features | |

| Analytical Frameworks | PathOmCLIP [38] | Histology-transcriptomics alignment | Bridges digital pathology with molecular profiling |

| scPlantFormer [38] | Cross-species cell annotation | Lightweight foundation model with 92% accuracy | |

| Nicheformer [38] | Spatial cellular niche modeling | Contextualizes cells within tissue architecture |

Future Directions and Implementation Roadmap

The clinical implementation of single-cell epigenomics is accelerating, driven by computational advances and decreasing sequencing costs. Emerging opportunities include the development of epigenetic diagnostic classifiers that complement traditional histopathology, therapy response prediction algorithms based on chromatin accessibility patterns, and minimal residual disease monitoring through epigenetic tracing of cancer clones [35] [36]. Realizing this potential requires continued refinement of wet-lab protocols to enhance reproducibility and computational methods to improve interpretability and clinical actionability.

Critical implementation priorities include establishing standardized benchmarking frameworks, developing multimodal knowledge graphs that integrate epigenetic data with clinical outcomes, and creating collaborative ecosystems that bridge computational scientists, clinical researchers, and diagnostic developers [38]. As these technologies mature, single-cell epigenomics is poised to transform precision medicine by revealing the regulatory underpinnings of disease at unprecedented resolution, enabling earlier diagnosis, more precise stratification, and targeted epigenetic therapies.

Bench to Bioinformatics: A Troubleshooting Guide for Robust Single-Cell Epigenomic Data

In single-cell epigenomic research, the journey to high-resolution data begins long before sequencing. The critical first step of sample preparation, particularly tissue dissociation into viable single-cell suspensions, is a profound source of technical variability that can dictate the success or failure of downstream applications. [39] Inadequate dissociation protocols directly compromise data quality by altering cellular transcriptomes, reducing cell type diversity, and introducing artifacts that obscure true biological signals. [39] [40] This guide addresses common pitfalls and provides troubleshooting strategies to ensure your dissociation methods yield high-quality, representative single-cell data, thereby enhancing the resolution and accuracy of your epigenomic research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)