Decoding the 3D Genome: A Comprehensive Guide to Hi-C and 3C-Based Technologies for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive examination of Hi-C and 3C-based technologies for mapping the three-dimensional architecture of the genome.

Decoding the 3D Genome: A Comprehensive Guide to Hi-C and 3C-Based Technologies for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of Hi-C and 3C-based technologies for mapping the three-dimensional architecture of the genome. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles, methodological applications across disease research, troubleshooting for experimental and computational challenges, and comparative validation of analytical tools. By integrating the most current research and practical insights, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to effectively apply chromatin conformation capture techniques in uncovering novel therapeutic targets and advancing epigenetic drug discovery.

The Spatial Genome Revolution: Understanding 3D Chromatin Architecture and 3C Principles

The genome of a eukaryotic cell presents a profound paradox of scale. The human genome, for instance, comprises approximately two meters of DNA, which must be efficiently compacted into a nucleus that is often less than 10 micrometers in diameter—a feat analogous to packing 40 kilometers of fine thread into a tennis ball [1]. For decades, our understanding of the genome was largely confined to its one-dimensional sequence of nucleotides. However, it is now unequivocally clear that the process of compaction is not a random entanglement. Instead, it is a highly sophisticated and dynamic architectural process, essential for the very function of the cell [1]. Each cell must constantly negotiate a dynamic equilibrium between the demand for extreme packaging and the critical need to access its genetic information for fundamental processes such as gene expression, DNA replication, and repair [1].

The solution to this packaging paradox lies in the three-dimensional (3D) organization of the genome. Rather than a simple linear code, the genome exists as a functional, folded landscape. This landscape is organized hierarchically, beginning with the confinement of individual chromosomes into distinct nuclear volumes known as chromosome territories [2]. Within these territories, the chromatin is further segregated into large-scale active ('A') and inactive ('B') compartments [2]. At a finer resolution, these compartments are built from smaller, self-interacting regulatory units called Topologically Associating Domains (TADs), which in turn are shaped by specific, point-to-point chromatin loops [1] [2]. This intricate architecture is far from static or merely structural; it represents a critical layer of gene regulation. By folding in three dimensions, the genome can bring distant regulatory elements, such as enhancers and silencers, into direct physical contact with their target gene promoters, an act that is fundamental to controlling gene expression [1].

The functional importance of the 3D genome is starkly illustrated when its architecture is compromised. A growing body of evidence now links disruptions in this complex folding to a wide spectrum of human diseases, from developmental disorders to cancer [1]. Chromosomal rearrangements, a hallmark of many cancers, do more than simply alter the linear sequence; they can catastrophically rewire the 3D landscape. For example, the translocation of a potent enhancer near a proto-oncogene, or the breakdown of a TAD boundary that normally insulates an oncogene from activating elements, can lead to aberrant gene expression and drive tumorigenesis [1]. Consequently, mapping the 3D genome provides invaluable insights into the structural and functional basis of disease, uncovering novel mechanisms of pathogenesis [1]. This application note details the protocols and applications of the 3C-based technology family, the primary toolkit for dissecting this 3D genomic architecture.

The 3C Technology Family: From Targeted Queries to Genome-Wide Maps

The development of Chromosome Conformation Capture (3C) and its derivatives has been the driving force behind the 3D genomics revolution [1]. First described in 2002, the foundational 3C method provided a powerful new logic: converting the transient, physical proximity of genomic loci into stable, quantifiable DNA ligation products [3] [1]. This conceptual leap bridged the gap between physical structure and genetic sequence, allowing researchers, for the first time, to create high-resolution maps of the folded genome. The evolution of this toolkit, from the targeted queries of 3C to the genome-wide vistas of Hi-C, has transformed our view of the genome from a static blueprint to a dynamic, four-dimensional entity. The members of this family can be classified based on the scope of interactions they interrogate [1].

Table 1: The 3C Technology Family: Scope and Applications

| Technology | Interaction Scope | Key Principle | Primary Application | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3C | One-vs-One | Ligation detection via qPCR with specific primers | Hypothesis testing of a single, pre-defined interaction (e.g., enhancer-promoter) | [3] |

| 4C | One-vs-All | Inverse PCR from a single "bait" locus | Unbiased discovery of all genomic interactions for a single locus of interest | [3] |

| 5C | Many-vs-Many | Multiplexed ligation-mediated amplification | Mapping all interactions within a defined genomic region (e.g., a gene cluster) | [3] |

| Hi-C | All-vs-All | Genome-wide ligation with biotin pull-down and NGS | Unbiased, genome-wide mapping of chromatin interactions and global architecture | [3] [4] |

| Capture-C/HiCap | Targeted All-vs-All | Hi-C combined with oligonucleotide capture for specific loci | High-resolution mapping of interactions for a pre-selected set of genomic regions | [3] [5] |

| PCHi-C | Targeted All-vs-All | Hi-C with oligonucleotide capture for promoter regions | Genome-wide identification of all long-range interactions involving gene promoters | [6] |

Table 2: Comparison of Key Technical and Performance Characteristics

| Characteristic | 3C | 4C | Hi-C | Capture-Based Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Very High | High | Low to Medium (library depth dependent) | Very High |

| Throughput | Low | Medium | High | High (for targeted regions) |

| Prior Knowledge Required | High (both loci) | Medium (one locus) | None | High (for probe design) |

| Typical Cost | Low | Medium | High | Medium to High |

| Key Limitation | Low throughput; hypothesis-driven | Identifies interactions from one viewpoint only | High sequencing cost for high resolution | Limited to pre-defined regions |

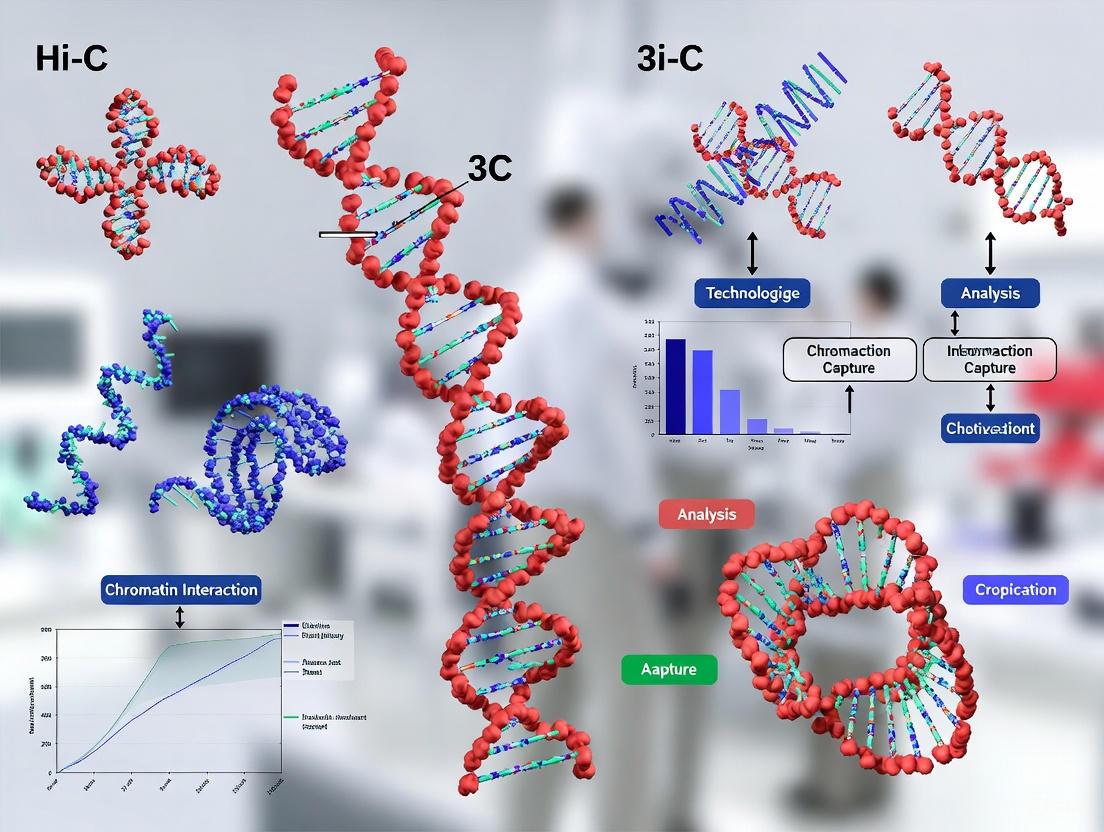

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and evolution of scope among the core 3C-based technologies:

Figure 1: The Evolution of 3C-Based Technologies. This diagram illustrates the progression from targeted interaction analysis to comprehensive genome-wide mapping and subsequent refinement through targeted enrichment strategies.

Core Protocol: A Detailed Guide to Hi-C

The Hi-C protocol is the most comprehensive "all-vs-all" method and serves as the foundation for many derivative techniques. The following section provides a detailed step-by-step protocol.

Step-by-Step Hi-C Experimental Workflow

The core principle of Hi-C involves converting spatial proximity into ligation junctions, which are then quantified via high-throughput sequencing [1] [4]. The following diagram outlines the complete experimental workflow:

Figure 2: Hi-C Experimental Workflow. The key steps from cell fixation to generation of sequencing-ready libraries.

In Vivo Cross-linking

- Procedure: Begin with intact, living cells. Add a cross-linking agent, most commonly 1-3% formaldehyde, directly to the cell culture medium. Incubate for 10-30 minutes at room temperature [3] [1].

- Purpose: Formaldehyde permeates the cell and nuclear membranes, creating covalent protein-DNA and protein-protein cross-links. This step "freezes" the chromatin in its native 3D conformation, preserving spatial relationships [1].

- Critical Considerations: Standardization is crucial. Over-cross-linking can create large, insoluble protein-DNA aggregates that reduce the efficiency of subsequent enzymatic digestion [1]. Quench the reaction with glycine.

Chromatin Fragmentation

- Procedure: Lyse the cross-linked cells and isolate nuclei. Digest the cross-linked chromatin with a restriction enzyme. While 6-cutter enzymes like HindIII were used historically, 4-cutter enzymes like DpnII or MboI are now preferred as they cut more frequently, enabling higher resolution [3] [7]. For even higher resolution, DNase I can be used for non-sequence-specific fragmentation [5].

- Purpose: To generate a complex library of chromatin fragments with cohesive ends. Spatially proximal fragments remain tethered by cross-links.

- Critical Considerations: The choice of restriction enzyme determines the potential resolution of the assay. Ensure digestion is complete to avoid bias.

End Repair and Biotinylation

- Procedure: The cohesive ends of the digested chromatin are filled in with nucleotides, including a biotinylated nucleotide (e.g., biotin-dATP) [4] [7].

- Purpose: The fill-in reaction creates blunt ends for ligation and marks the ligation junctions with biotin. This allows for the specific pull-down of chimeric fragments derived from ligation events, enriching for informative molecules during library preparation.

Proximity Ligation

- Procedure: The mixture of cross-linked, digested, and filled-in chromatin is subjected to ligation with DNA ligase under conditions of extreme dilution [1] [7].

- Purpose: The high dilution favors intramolecular ligation between DNA ends that are held in close proximity within the same cross-linked complex over random intermolecular ligation. This step selectively captures true 3D interactions, creating novel chimeric DNA molecules.

Reverse Cross-links and Purify DNA

- Procedure: Treat the ligated material with Proteinase K and heat to reverse the cross-links and degrade proteins. Purify the DNA using phenol-chloroform extraction or commercial kits [1] [7].

- Purpose: To remove proteins and recover the pure DNA library, which now contains a mixture of re-ligated original fragments and the chimeric ligation products of interest.

Shear DNA and Pull-down Biotinylated Fragments

- Procedure: Shear the purified DNA to a desired fragment size (e.g., 300-500 bp) using sonication or enzymatic methods. Incubate the sheared DNA with streptavidin-coated beads to capture the biotinylated fragments [4] [7].

- Purpose: Shearing prepares the DNA for sequencing library construction. The streptavidin pull-down enriches for fragments that contain a ligation junction, dramatically increasing the signal-to-noise ratio by removing non-informative fragments.

Library Prep and Paired-End Sequencing

- Procedure: Perform standard steps for next-generation sequencing library construction on the bead-bound DNA, including end-repair, adapter ligation, and PCR amplification. The library is then sequenced using paired-end sequencing [4] [7].

- Purpose: Paired-end sequencing is essential because each read pair is derived from two different, originally non-adjacent genomic loci that were ligated together. The two sequences are aligned individually to the reference genome to identify the interacting fragments.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Hi-C Protocols

| Reagent/Material | Function | Examples & Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Formaldehyde | Cross-linking agent to fix chromatin 3D structure. | Molecular biology grade, 1-3% final concentration in medium. |

| Restriction Enzyme | Fragments cross-linked chromatin at specific sites. | DpnII, HindIII, MboI; 4-cutter enzymes preferred for resolution. |

| DNA Ligase | Catalyzes ligation of proximally located DNA ends. | T4 DNA Ligase, high-concentration formulation. |

| Biotin-dATP | Labels ligation junctions for subsequent enrichment. | Used in the end-repair fill-in reaction. |

| Streptavidin Beads | Captures biotinylated fragments for library enrichment. | Magnetic beads for easy handling and washing. |

| Proteinase K | Reverses cross-links and digests proteins. | Molecular biology grade, for DNA purification post-ligation. |

| Next-Generation Sequencer | Determines the sequences of ligated fragments. | Illumina platforms standard for paired-end sequencing. |

Bioinformatics Analysis of Hi-C Data

The analysis of Hi-C data involves a series of specialized computational steps to transform raw sequencing reads into interpretable maps of chromatin interactions.

Preprocessing and Normalization

The initial steps are critical for ensuring data quality and correcting for technical biases [7].

- Quality Control and Read Trimming: Tools such as FastQC assess raw read quality. Trim Galore is then used to remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases [7].

- Mapping: Processed reads are aligned to a reference genome using aligners like Bowtie2. A key challenge is handling chimeric reads containing the ligation junction; strategies include iterative mapping or splitting reads at the restriction site [7].

- Read-pair Filtering: Mapped read pairs are filtered to remove artifacts. This includes removing pairs with incorrect orientations, pairs from fragments that are too close in linear genomic distance (likely self-ligation products), and PCR duplicates [7].

- Normalization: The filtered contact matrix contains biases from factors like GC content, mappability, and restriction site distribution. Normalization methods, such as ICE (Iterative Correction and Eigenvalue decomposition), are used to correct these biases, producing a "balanced" contact matrix where the number of contacts for a locus is proportional to its actual interaction frequency [7].

The following diagram illustrates the key bioinformatics steps from raw data to a normalized contact matrix:

Figure 3: Hi-C Data Preprocessing Pipeline. The workflow for converting raw sequencing data into a normalized matrix of interaction frequencies.

Identification of Chromatin Features

The normalized contact matrix is used to identify key features of 3D genome architecture at multiple scales [4] [7].

- Compartments (A/B): Calculated using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the normalized contact matrix. The first principal component (PC1) often separates the genome into two compartments: A (gene-rich, active) and B (gene-poor, inactive) [2].

- Topologically Associating Domains (TADs): Self-interacting genomic regions visible as triangles along the diagonal of a Hi-C heatmap. Multiple computational methods exist to identify TADs, including:

- Directionality Index (DI): Quantifies the bias in upstream vs. downstream interactions.

- Insulation Score: Identifies TAD boundaries as regions of low interaction frequency (insulators) between domains.

- Arrowhead Algorithm: Detects the corners of TADs from the contact matrix [7].

- Chromatin Loops: Point-to-point interactions, often mediated by CTCF and cohesin, that appear as off-diagonal dots in high-resolution contact maps. Tools like HiCCUPS are used for peak detection to identify these statistically significant interactions [4] [7].

3D Modeling and Visualization

Hi-C data can be used to model the 3D structure of the genome [7].

- Consensus Methods: Approaches like Multi-dimensional Scaling (MDS) convert contact frequencies into spatial distances to generate a single, consensus 3D structure. This provides an average model of chromatin conformation.

- Ensemble Methods: Techniques such as Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling generate a population of 3D structures that are all consistent with the Hi-C data. This is crucial for capturing the dynamic nature and heterogeneity of chromatin organization within a cell population [7].

Application Notes: Investigating 3D Genome Architecture in Colorectal Cancer

Integrated analyses of 3D genome architecture are revealing its critical role in disease. A recent study on colorectal cancer (CRC) provides a powerful example of how Hi-C and promoter-capture Hi-C (PCHi-C) can be applied to uncover novel disease mechanisms [6].

Integrated Analysis Workflow

The study integrated multiple genomic datasets from CRC models [6]:

- PCHi-C and Hi-C: To map high-resolution promoter interactions and global chromatin architecture.

- RNA-seq and scRNA-seq: To correlate structural changes with gene expression dysregulation.

- ChIP-seq: To assess enrichment of activation-associated histone modifications (H3K27ac, H3K4me3) at enhancer regions.

- Experimental Validation: ChIP-quantitative PCR was performed in a malignant CRC cell line (HT29) versus an embryonic cell line (NT2D1) to validate findings.

Key Findings and Implications

The integrated analysis revealed [6]:

- Structural Instability: CRC cells exhibited significant genomic structural instability, which was closely associated with altered transcriptional programs.

- Dysregulated Genes: The study identified nine key dysregulated genes, including long non-coding RNAs (e.g., MALAT1, NEAT1), small nucleolar RNAs, and protein-coding genes (e.g., TMPRSS11D, DSG4), all showing substantial upregulation in CRC.

- Epigenetic Activation: Enhancer regions associated with these genes showed enriched activation-associated histone modifications (H3K27ac, H3K4me3), indicating possible transcriptional activation driven by altered chromatin interactions.

- Biomarker Potential: The identified genes represent potential biomarkers for colorectal cancer, with implications for future diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

This application demonstrates the power of combining 3C-based technologies with complementary functional genomic datasets to move from observing structural changes to understanding their functional consequences in disease.

The eukaryotic genome is packaged into the nucleus through a multi-layered hierarchical architecture that is fundamental to nuclear processes such as gene regulation, DNA replication, and cellular differentiation. This organization transforms the linear DNA sequence into a complex three-dimensional structure, facilitating precise spatiotemporal control of genomic functions. The significance of studying this architecture lies in its profound impact on gene expression; regulatory elements such as enhancers and promoters often lie far apart in the linear genome but are brought into proximity through spatial folding, creating functional interactions that dictate cellular identity and function. Disruptions in this delicate architecture have been implicated in various developmental disorders and cancers, underscoring its biological and clinical relevance.

Hi-C and related chromosome conformation capture (3C) technologies have revolutionized our understanding of 3D genome organization by capturing genome-wide spatial proximity information. These methods have enabled researchers to move beyond the one-dimensional genetic code to explore the complex topological principles governing nuclear architecture. The hierarchical levels of chromatin organization—from chromosome territories to chromatin loops—represent distinct but interconnected scales of structural complexity, each with specific functional implications. This application note details the experimental and computational approaches for investigating these hierarchical levels, providing a framework for researchers exploring the relationship between genome structure and function.

Theoretical Framework: Levels of Chromatin Organization

The nuclear genome is organized into a series of increasingly refined structural units, each characterized by distinct spatial and functional properties. At the highest level, chromosome territories represent the discrete nuclear volumes occupied by individual chromosomes, which are not randomly positioned but exhibit preferential radial arrangements correlated with gene density and chromosome size. Within these territories, the genome is further partitioned into A/B compartments, which are large-scale, megabase-sized segments that segregate active (A) and inactive (B) chromatin regions, reflecting their transcriptional status and epigenetic landscapes.

At a finer scale, topologically associating domains (TADs) are sub-megabase regions characterized by high internal interaction frequencies and strong boundary insulation from adjacent domains. First discovered in 2012 through Hi-C studies, TADs are considered fundamental structural and functional units of the genome that facilitate appropriate enhancer-promoter interactions while preventing aberrant cross-talk between neighboring regulatory domains. The hierarchical nature of TADs is evidenced by the presence of sub-TADs nested within larger meta-TADs, providing a structural framework that balances stability with functional plasticity during cellular differentiation and development.

At the most granular level, chromatin loops bring distal genomic elements, such as enhancers and promoters, into close spatial proximity, enabling direct regulatory interactions. These loops are often anchored by CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF) and cohesin complexes, which facilitate loop extrusion through a mechanism that involves active translocation of chromatin fibers until encountering boundary elements. This multi-scale organization—from territories to loops—creates a sophisticated structural framework that orchestrates gene regulatory programs and maintains genomic stability.

Table 1: Characteristics of Chromatin Organization Levels

| Organization Level | Size Range | Key Features | Primary Functions | Identifying Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chromosome Territories | 50-250 Mb | Discrete nuclear volumes for each chromosome; non-random positioning | Spatial segregation of chromosomes; facilitating chromosomal interactions | FISH, Hi-C, microscopy |

| A/B Compartments | 1-10 Mb | Segregation of active (A) and inactive (B) chromatin; correlated with epigenetic marks | Separating transcriptionally active and repressed regions | Hi-C principal component analysis |

| Topologically Associating Domains (TADs) | 0.1-1 Mb | High internal interaction frequency; strong boundary insulation | Constraining enhancer-promoter interactions; functional insulation | Hi-C contact matrix analysis; insulation scoring |

| Chromatin Loops | <100 kb | Bringing distal elements into proximity; often CTCF/cohesin-mediated | Facilitating specific enhancer-promoter interactions | Hi-C at high resolution; ChIA-PET; PLAC-Seq |

Visualizing Chromatin Hierarchy

The following diagram illustrates the nested, hierarchical relationship between these organizational levels, from the entire nucleus down to specific chromatin loops that enable gene regulation.

Experimental Methods for Studying Chromatin Architecture

Hi-C and Its Variants

Hi-C technology represents the cornerstone of 3D genomics research, enabling genome-wide mapping of chromatin interactions through a sophisticated biochemical approach that combines proximity ligation with high-throughput sequencing. The standard Hi-C protocol begins with formaldehyde cross-linking of cells to capture spatial proximities between genomic loci, followed by chromatin digestion with restriction enzymes (frequently MboI, HindIII, or DpnII) that cleave DNA at specific recognition sites. The resulting fragmented DNA ends are then labeled with biotinylated nucleotides and subjected to proximity ligation under dilute conditions that favor intra-molecular ligation events between cross-linked fragments. After reversing cross-links and purifying DNA, the biotin-labeled ligation junctions are enriched using streptavidin beads and prepared for paired-end sequencing, generating data that ultimately yields a genome-wide contact probability matrix [8] [9].

Several Hi-C variants have been developed to address specific research questions. In situ DNase Hi-C replaces restriction enzyme digestion with DNase I, generating libraries with higher effective resolution than traditional Hi-C approaches [10]. Single-cell Hi-C (scHi-C) technologies enable the profiling of chromatin architecture in individual cells, revealing cell-to-cell variability in chromatin organization that is masked in population-averaged bulk experiments [11]. Recent advancements in scHi-C include Droplet Hi-C, which utilizes microfluidic devices to profile tens of thousands of cells simultaneously, dramatically improving scalability and enabling applications in heterogeneous tissues [12]. Capture-based methods such as Capture Hi-C and Capture-C use oligonucleotide probes to enrich for specific genomic regions of interest, providing higher resolution at targeted loci while reducing sequencing costs [13].

Complementary Methodologies

Beyond Hi-C, several complementary technologies provide additional insights into chromatin architecture. Chromatin Interaction Analysis with Paired-End Tag Sequencing (ChIA-PET) combines chromatin immunoprecipitation with proximity ligation to map interactions mediated by specific protein factors such as RNA polymerase II or CTCF. PLAC-Seq and HiChIP represent more recent protein-centric chromatin interaction methods that offer improved efficiency and lower input requirements compared to ChIA-PET. Imaging-based approaches including fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and its super-resolution variants provide direct visualization of spatial proximities between specific genomic loci in individual cells, serving as valuable validation tools for Hi-C findings [8] [13].

Table 2: Key Chromatin Conformation Capture Technologies

| Technology | Resolution | Throughput | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hi-C | 1 kb-100 kb | Genome-wide | Mapping all chromatin interactions; identifying TADs and compartments | Unbiased genome-wide coverage; comprehensive | High sequencing depth required; population averaging |

| DNase Hi-C | <1 kb | Genome-wide | High-resolution interaction mapping | Higher resolution than restriction-based Hi-C | Complex protocol; optimization required |

| Single-cell Hi-C | 50 kb-1 Mb | Thousands of cells | Cellular heterogeneity; cell type-specific architecture | Resolves cell-to-cell variation | Sparse data per cell; technical noise |

| Droplet Hi-C | 10 kb-100 kb | Tens of thousands of cells | Complex tissues; cancer heterogeneity | High throughput; commercial microfluidics | Specialized equipment required |

| Capture Hi-C | 1-5 kb | Targeted regions | Promoter-enhancer interactions; disease-associated variants | High resolution at targeted regions; cost-effective | Limited to predefined regions |

| ChIA-PET | 1-10 kb | Protein-specific | Protein-mediated interactions (CTCF, Pol II, etc.) | Identifies factor-bound interactions | Antibody-dependent; complex protocol |

Protocol: Droplet Hi-C for Single-Cell Chromatin Architecture

Principle: Droplet Hi-C combines in situ Hi-C with commercial microfluidic technology to enable high-throughput, single-cell profiling of chromatin architecture in complex tissues [12].

Workflow Steps:

- Cell Preparation and Cross-linking: Harvest cells or nuclei and cross-link with 1-2% formaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature. Quench with 125 mM glycine for 15 minutes.

- Chromatin Digestion: Resuspend cross-linked cells in appropriate restriction enzyme buffer and digest with 50-100 units of MboI or DpnII for 2 hours at 37°C with agitation.

- Marking and Ligation: Fill restriction ends with biotinylated nucleotides using Klenow fragment, followed by proximity ligation with T4 DNA ligase for 2-4 hours at room temperature.

- Reverse Cross-linking and DNA Purification: Treat with Proteinase K overnight at 65°C, followed by RNase A treatment and DNA purification using magnetic beads.

- Nuclei Preparation for Droplets: Resuspend purified nuclei in cold PBS + 0.1% BSA at optimal concentration (700-1,200 nuclei/μL).

- Droplet Generation: Load nuclei suspension into 10x Genomics Single Cell ATAC chip along with barcoding beads and partitioning oil. Run on Chromium Controller to generate single-cell droplets.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Perform GEM incubation, clean-up, and PCR amplification according to manufacturer's protocol. Sequence on Illumina platform (recommended: 200-500 million read pairs per 10,000 cells).

Critical Parameters:

- Cell viability and integrity: >90% viability recommended

- Cross-linking optimization: Avoid over-cross-linking to maintain accessibility

- Nuclei concentration: Precisely titrate to minimize multiplets while maintaining throughput

- Sequencing depth: Aim for 50,000-100,000 unique read pairs per cell for compartment-level analysis

Applications: This protocol is particularly suited for heterogeneous tissues such as brain cortex or tumor samples, where identifying cell-type-specific chromatin organization patterns is essential for understanding biological function and disease mechanisms [12].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram outlines the key steps in a standard Hi-C experimental workflow, from cell preparation to data analysis.

Computational Analysis of Hi-C Data

Data Processing Pipeline

The computational analysis of Hi-C data begins with processing raw sequencing reads to generate normalized contact matrices that accurately represent spatial proximity frequencies. The initial steps involve quality control of FASTQ files using tools like FastQC, followed by alignment of paired-end reads to a reference genome using specialized Hi-C mappers such as HiC-Pro, Juicer, or HiCUP, which account for the unique ligation junction structure of Hi-C data. After alignment, valid interaction pairs are identified by filtering out artifacts including PCR duplicates, random ligation events, and reads mapping to identical fragments. The filtered reads are then binned into matrices at various resolutions (e.g., 1 Mb, 100 kb, 50 kb, 25 kb, 10 kb, 5 kb, or 1 kb) based on research questions and sequencing depth, generating raw contact frequency matrices [8] [13].

A critical step in Hi-C data processing is matrix normalization, which corrects for technical biases including GC content, mappability, and restriction enzyme fragment sizes. Multiple normalization strategies have been developed, including Iterative Correction and Eigenvector decomposition (ICE) which equalizes the total number of contacts per row and column, and Knight-Ruiz (KR) matrix balancing which converges to a similar result through matrix balancing algorithms. These normalization methods help distinguish biologically meaningful interaction patterns from technical artifacts, enabling accurate downstream analysis of chromatin architecture [13].

Identifying Hierarchical Chromatin Features

Each level of chromatin organization requires specific computational approaches for identification and characterization. A/B compartments are typically identified through principal component analysis (PCA) of the normalized contact matrix, with the first principal component segregating the genome into two compartments: positive values corresponding to the active A compartment (gene-rich, transcriptionally active) and negative values to the inactive B compartment (gene-poor, transcriptionally repressed) [13] [14].

TADs and their boundaries are detected using algorithms that identify regions with high internal interaction frequency and sharp transitions at boundaries. Popular methods include directionality index (DI) approaches that quantify the bias in upstream versus downstream interactions, insulation scoring which identifies genomic positions with minimal transverse interactions, and domain callers such as Arrowhead that directly identify the triangular blocks of elevated interaction in contact matrices. The strength of TAD boundaries can be quantified using boundary scores, with stronger boundaries typically enriched for architectural proteins like CTCF and cohesin [11] [13].

Chromatin loops are identified as statistically significant peaks of interaction after controlling for factors such as genomic distance and sequencing depth. Methods like Fit-Hi-C and HiCCUPS use binomial or Poisson models to detect significant interactions against a background model, with the latter specifically designed to identify punctate interactions characteristic of loop domains. Recent advances incorporate deep learning approaches such as Higashi and SnapHiC to improve loop detection sensitivity, particularly in single-cell Hi-C data where sparsity remains a significant challenge [11] [12].

Successful investigation of chromatin architecture requires a combination of wet-lab reagents, computational tools, and data resources. The following table details essential components of the chromatin conformation research toolkit.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Chromatin Architecture Studies

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Application | Examples/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | Formaldehyde | Cross-linking chromatin interactions | Methanol-free, high purity |

| Restriction Enzymes | Chromatin fragmentation | DpnII, MboI, HindIII, or DNase I | |

| Biotinylated Nucleotides | Marking ligation junctions | Biotin-14-dATP | |

| T4 DNA Ligase | Proximity ligation | High-concentration | |

| Streptavidin Beads | Enriching biotinylated fragments | Magnetic beads | |

| Commercial Kits | Droplet Hi-C Platform | Single-cell chromatin conformation | 10x Genomics Single Cell ATAC + Multiome |

| Cross-linking Kits | Standardized fixation | Thermo Fisher Pierce | |

| Library Prep Kits | Sequencing library construction | Illumina TruSeq | |

| Computational Tools | Hi-C Processing | Data processing and normalization | HiC-Pro, Juicer, HiCUP |

| TAD Callers | Domain identification | Arrowhead, DomainCaller, InsulationScore | |

| Loop Callers | Significant interaction detection | HiCCUPS, Fit-Hi-C, MUSTACHE | |

| Visualization | Data exploration and presentation | Juicebox, HiGlass, 3D Genome Browser | |

| Data Resources | Public Data Repositories | Reference datasets | 4DN DCIC, GEO, 3D Genome Browser |

| Genome Browsers | Integration and visualization | 3D Genome Browser, WashU EpiGenome Browser |

Applications in Biological Systems and Disease Contexts

Neuronal Chromatin Organization

Studies of chromatin architecture in neuronal cells have revealed unique organizational features that may underlie brain-specific functions and susceptibility to neurological disorders. Compared to non-neuronal cells, neurons exhibit weaker compartmentalization with elevated short-range A-A interactions and reduced long-range B-B contacts, suggesting a distinct large-scale chromatin organization. Neurons also display cell-type-specific TAD boundaries enriched with active histone marks such as H3K4me3 and H3K27ac, potentially reflecting specialized gene regulatory programs required for neuronal function. Additionally, neurons show an increased number of chromatin loops, possibly mediated by elevated expression of cohesin complex proteins that facilitate loop extrusion [14].

These unique architectural features have functional implications for brain development and function. For instance, the formation of neuron-specific inactive subcompartments enriched with H3K9me3 histone marks helps sequester ERV2 retrotransposon elements, preventing their activation and maintaining genomic stability in long-lived neuronal populations. Disruption of these architectural features through mutations in genes encoding architectural proteins like CTCF or cohesin subunits has been linked to neurodevelopmental disorders, highlighting the importance of proper chromatin organization for brain health [14].

Cancer Genomics

Chromatin architecture studies in cancer have revealed widespread reorganization of the 3D genome that contributes to oncogenic transformation and progression. Tumor cells frequently exhibit compartment switching, where genomic regions normally in the inactive B compartment transition to the active A compartment, leading to aberrant oncogene expression, or vice versa for tumor suppressor genes. TAD boundary disruptions are also common in cancer, potentially caused by structural variations or mutations in boundary-associated elements, resulting in novel regulatory interactions that drive oncogenic expression programs. For example, boundary disruptions can place oncogenes under control of powerful enhancers normally insulated in their native TAD context [12] [15].

Single-cell chromatin architecture methods like Droplet Hi-C have enabled the identification of extrachromosomal DNA (ecDNA) in tumor cells, which often harbor amplified oncogenes and exhibit unique chromatin interaction patterns. These ecDNA elements can form neochromosomes with enhanced enhancer-promoter interactions that drive high-level oncogene expression, contributing to tumor heterogeneity and therapy resistance. The ability to profile chromatin architecture at single-cell resolution in heterogeneous tumor samples provides unprecedented opportunities to understand clonal dynamics and identify architectural vulnerabilities that could be therapeutically targeted [12].

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

The field of 3D genomics continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends shaping future research directions. Multimodal single-cell technologies that simultaneously profile chromatin architecture alongside other molecular modalities such as gene expression, DNA methylation, and histone modifications are providing increasingly comprehensive views of genome regulation. Methods like GAGE-seq and multimodal Droplet Hi-C enable direct correlation of chromatin structure with transcriptional output in the same cell, overcoming limitations of inference from separate experiments [12] [15].

Artificial intelligence and deep learning approaches are increasingly being applied to overcome data sparsity in single-cell Hi-C and predict high-resolution chromatin structures from sequence features. Methods like Higashi and scDEC-Hi-C use graph neural networks and variational autoencoders to impute missing contacts and extract meaningful biological patterns from sparse single-cell data [11]. These approaches show particular promise for identifying disease-associated architectural variations in clinical samples where material may be limited.

From a clinical perspective, growing understanding of chromatin architecture is revealing its potential as a diagnostic and therapeutic target. The unique chromatin organization patterns in cancer cells may serve as architectural biomarkers for disease classification and prognosis, while the development of small molecules targeting architectural proteins represents a promising therapeutic avenue. As our knowledge of chromatin hierarchy deepens, we move closer to a comprehensive understanding of how genome structure governs function in health and disease, opening new possibilities for targeted interventions in conditions ranging from developmental disorders to cancer and neurodegenerative diseases.

For over a century, the fundamental question of how meters of DNA are packaged into a microscopic nucleus while maintaining regulated genomic function has captivated scientists. Early microscopic observations first hinted at a non-random nuclear organization, but the tools to probe this architecture at high resolution remained elusive for decades. The development of Chromosome Conformation Capture (3C) in 2002 marked a revolutionary turning point, establishing a biochemical approach to complement microscopic studies and finally enabling detailed investigation of the genome's spatial architecture [3] [16]. This innovation, which converted physical proximity between genomic loci into quantifiable DNA ligation products, launched a new field dedicated to understanding the functional implications of the three-dimensional (3D) genome [1].

This application note traces the critical historical milestones that transformed our understanding of nuclear organization, from early microscopic observations to the sophisticated 3C-based technologies used today. We frame these developments within the context of modern 3D genome research, providing detailed methodological insights and resource guidance to empower researchers in leveraging these tools for advanced genomic studies and therapeutic discovery.

The Microscopy Era: Initial Insights into Nuclear Organization

Long before molecular approaches emerged, microscopy provided the first glimpses into nuclear organization, establishing foundational concepts that would guide future research.

Table 1: Key Historical Discoveries in Microscopy (Pre-2002)

| Year | Scientist(s) | Discovery | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1879 | Walther Flemming | Coined the term "chromatin" [3] | Established the material basis of heredity |

| 1928 | Emil Heitz | Distinguished heterochromatin & euchromatin [3] [17] | Revealed structural/functional chromatin differences |

| 1982 | Cremer et al. | Discovered chromosome territories [3] [17] | Showed chromosomes occupy distinct nuclear spaces |

| 1993 | Cullen et al. | Nuclear Ligation Assay [3] [18] | Precursor to 3C; showed enhancer-promoter interaction |

These microscopic studies revealed that the nucleus is highly organized, with chromosomes occupying distinct territories and chromatin existing in functionally distinct states (euchromatin and heterochromatin) [17] [16]. The radial positioning of chromosomes was found to be non-random, with gene-dense chromosomes typically located more internally than gene-poor chromosomes [17]. Furthermore, studies tracking individual genes revealed that their nuclear positioning could change in relation to their transcriptional status, with active genes often moving away from the nuclear periphery or repressive heterochromatic regions [17] [16]. However, microscopy remained limited in throughput and resolution, unable to simultaneously study multiple specific genomic loci at high resolution across a cell population [8] [16]. These limitations set the stage for a molecular biology-based approach that would overcome these constraints.

The 3C Revolution: A Molecular Biology Breakthrough

The pivotal shift from observational to biochemical analysis occurred in 2002 when Job Dekker and colleagues introduced the Chromosome Conformation Capture (3C) methodology [3] [16]. This innovative technique was based on a powerful concept: converting the physical proximity of genomic loci in 3D space into stable, quantifiable DNA molecules [1].

The Core 3C Methodology

The original 3C protocol involves a series of precise biochemical steps [1] [19]:

- In Vivo Cross-linking: Cells are treated with formaldehyde (typically 1-3%) to create covalent bonds between spatially proximate DNA segments and their associated proteins, effectively "freezing" the chromatin's 3D conformation [3] [19].

- Chromatin Fragmentation: The cross-linked chromatin is digested with a restriction enzyme (e.g., HindIII, EcoRI, or DpnII) that cuts at specific recognition sites, fragmenting the genome [3] [1].

- Proximity Ligation: Under highly diluted conditions that favor intramolecular ligation, DNA ligase joins the cross-linked fragments. This creates chimeric DNA molecules from loci that were physically proximate in the nucleus [3] [16].

- Analysis and Quantification: After reversing cross-links, the ligation products are purified. Specific interactions between two predefined genomic loci are quantified using quantitative PCR (qPCR) with primers specific to each locus [1].

This "one-versus-one" approach [1] was first successfully applied to study the conformation of yeast chromosome III [16] and soon adapted to demonstrate that enhancers physically loop to their target promoters in the mammalian β-globin locus, forming what was termed an active chromatin hub (ACH) [17] [16].

Figure 1: The Core 3C Workflow. This diagram illustrates the fundamental steps of the Chromosome Conformation Capture protocol, from cell fixation to data analysis.

The 3C Technology Family: An Expanding Toolkit

The success of 3C in confirming specific chromatin interactions sparked demand for higher-throughput methods, leading to the development of an entire family of 3C-based technologies [1] [18]. These methods share the core 3C principles but differ dramatically in scope and application.

Table 2: The 3C Technology Family: Scope and Applications

| Method | Scope | Key Principle | Primary Application | Year Introduced |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3C [1] | One-vs-One | Ligation + qPCR with specific primers | Testing interactions between two predefined loci | 2002 [3] |

| 4C [1] | One-vs-All | Circularization + inverse PCR | Identifying all genomic interactions of a single "bait" locus | 2006 [3] |

| 5C [1] | Many-vs-Many | Multiplexed ligation-mediated amplification | Mapping interaction networks within a targeted genomic region | 2006 [3] |

| Hi-C [1] | All-vs-All | Biotinylated fill-in + pull-down before sequencing | Genome-wide, unbiased mapping of all chromatin interactions | 2009 [3] |

| ChIA-PET [3] | Protein-centric | Chromatin Immunoprecipitation + ligation | Identifying all interactions mediated by a specific protein | 2009 [3] |

The progression from 3C to Hi-C represents a logical expansion of experimental scale, moving from targeted hypothesis testing to unbiased, discovery-driven research [1]. This evolution was critically enabled by the advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS), which provided the necessary throughput to analyze the complex libraries generated by genome-wide methods [8] [1].

Figure 2: Evolution of 3C-based Technologies. The expansion from specific interaction testing to genome-wide discovery.

Detailed Hi-C Protocol: A Step-by-Step Guide

As the most widely used genome-wide method, Hi-C warrants particular attention. The following protocol outlines the critical steps for generating high-quality Hi-C data, highlighting key considerations for success.

Sample Preparation and Cross-Linking

Begin with intact, living cells. Treat with 1% formaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature to cross-link chromatin [20]. Immediately quench the reaction with glycine (final concentration 0.25 M) to prevent over-cross-linking, which can cause excessive chromatin condensation and impede restriction enzyme digestion [20]. The optimal cross-linking time is cell type-dependent and should be determined empirically.

Chromatin Digestion and Biotin Labeling

After cell lysis, digest the cross-linked chromatin with a restriction enzyme. The choice of enzyme determines potential resolution: 6-cutters (e.g., HindIII; ~4 kb fragments) are suitable for genome-wide interaction mapping, while 4-cutters (e.g., DpnII, MboI; ~256 bp fragments) enable higher-resolution studies [20]. Verify digestion efficiency by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, where fragments of 1-10 kb indicate sufficient cleavage [20]. Subsequently, fill the restriction fragment ends with biotin-labeled nucleotides using the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase [20] [8].

Proximity Ligation and DNA Purification

Perform ligation under highly diluted conditions (e.g., 1 ng/μL DNA) with T4 DNA ligase at 16°C for 4 hours to favor intramolecular ligation of cross-linked fragments [20]. Gentle mixing during incubation ensures reaction homogeneity. Following ligation, reverse the cross-links with proteinase K and purify the DNA. The resulting library contains a mixture of original and chimeric ligation products.

Library Preparation and Sequencing

Shear the purified DNA and perform a biotin pull-down using streptavidin magnetic beads to enrich for fragments containing ligation junctions [20] [8]. Prepare sequencing libraries from these enriched fragments using standard protocols. The use of Unique Dual Indexes (UDIs) enables multiplex sequencing [20]. For complex genomes, the final library should have a main peak in the 400-700 bp range when analyzed on an Agilent Bioanalyzer [20].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Hi-C

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Protocol | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-linking Agent | Formaldehyde [20] [1] | Fixes 3D chromatin structure | Concentration & time critical; over-cross-linking reduces efficiency |

| Restriction Enzymes | HindIII (6-cutter), DpnII, MboI (4-cutters) [20] | Fragments genome at specific sites | 4-cutters provide higher potential resolution |

| Labeling System | Biotin-dNTPs, Klenow Fragment [20] [8] | Marks fragment ends for enrichment | Enables specific pull-down of ligation junctions |

| Ligation System | T4 DNA Ligase [20] [1] | Joins cross-linked fragments | Diluted conditions favor intramolecular ligation |

| Enrichment System | Streptavidin Magnetic Beads [20] [8] | Isolates biotinylated junctions | Batch-to-batch variability should be tested |

Impact and Future Directions in 3D Genomics

The application of 3C-based technologies has fundamentally transformed our understanding of genome biology, revealing several fundamental principles of 3D genome organization. These include the segregation of the genome into active (A) and inactive (B) compartments [17], the identification of Topologically Associating Domains (TADs) as fundamental building blocks of chromatin organization [18], and the role of specific chromatin loops mediated by the CTCF protein and cohesin complex in bringing regulatory elements into proximity with their target genes [17] [18].

Technological development continues to push the field forward. DNase Hi-C replaces restriction enzymes with the non-sequence-specific nuclease DNase I, overcoming resolution limitations imposed by restriction site distribution and enabling higher-resolution mapping [5]. Single-cell Hi-C methods now allow the study of cell-to-cell heterogeneity in chromosome conformation, moving beyond population averages [3] [18]. Furthermore, Micro-C utilizes micrococcal nuclease (MNase) for fragmentation, achieving nucleosome-resolution contact mapping and revealing the fine-scale organization of the chromatin fiber [18].

These technologies are increasingly applied in disease contexts, particularly cancer research, where they have revealed how chromosomal rearrangements and disruptions in 3D genome architecture can lead to oncogene activation [1]. As these methods continue to evolve and integrate with other genomic and epigenomic approaches, they promise to provide unprecedented insights into the role of nuclear organization in health and disease, opening new avenues for therapeutic intervention.

The organization of the genome within the nucleus is a critical layer of gene regulation that extends far beyond its linear DNA sequence. In eukaryotic cells, the immense task of packaging approximately two meters of DNA into a nucleus mere micrometers in diameter results in a highly sophisticated and dynamic three-dimensional architecture [1]. This spatial arrangement is non-random; it forms a foundational framework for essential nuclear processes, including gene expression, DNA replication, and repair. For decades, the tools to study this architecture were limited to microscopic techniques, which, while valuable, lacked the molecular resolution to uncover sequence-specific interactions.

The development of Chromosome Conformation Capture (3C) technology marked a revolutionary breakthrough. Its core, innovative principle is the conversion of transient spatial proximity between distant genomic loci into stable, quantifiable DNA molecules. This biochemical transformation allows researchers to infer the three-dimensional organization of chromatin by analyzing a one-dimensional DNA library, effectively bridging the gap between physical structure and genetic sequence [1]. This document details the fundamental protocol of 3C and its application in modern drug discovery and development pipelines.

The Core Biochemical Principle: From Proximity to Product

The power of 3C lies in its elegant experimental workflow, which captures a snapshot of nuclear architecture and translates it into a form amenable to molecular analysis. The process can be broken down into four critical stages.

Step-by-Step Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the sequential biochemical steps that transform in vivo chromatin interactions into detectable chimeric DNA ligation products.

Step 1: In Vivo Cross-Linking The process begins with intact cells treated with a cross-linking agent, most commonly formaldehyde. This reagent permeates the cell and nuclear membranes, creating covalent bonds between DNA and the proteins that bind it, as well as between closely apposed proteins. This critical step effectively "freezes" the chromatin in its native 3D conformation, preserving the spatial relationships between genomic elements that were proximate at the moment of fixation [1] [21].

Step 2: Chromatin Fragmentation After cell lysis, the cross-linked chromatin is digested with a restriction enzyme (e.g., HindIII, DpnII, or EcoRI). The enzyme cuts the DNA at specific recognition sites, generating a complex mixture of chromatin fragments. Crucially, DNA fragments that were spatially proximal in the nucleus remain physically tethered together by the network of cross-linked protein complexes, even if they are megabases apart in the linear genome [21].

Step 3: Proximity Ligation This is the conceptual heart of the 3C method. The mixture of digested chromatin fragments is subjected to ligation with DNA ligase under highly diluted conditions. This dilution ensures that the concentration of chromatin complexes is low, thereby minimizing random collisions and ligation events between fragments from different complexes (intermolecular ligation). Instead, the reaction strongly favors ligation between the sticky ends of DNA fragments that are already held in close proximity within the same cross-linked complex (intramolecular ligation). This step selectively captures true 3D interactions, creating novel, chimeric DNA molecules where the junction represents a point of spatial contact in the original nucleus [1] [21].

Step 4: Analysis and Quantification The cross-links are reversed, and proteins are degraded, releasing the DNA. The resulting library contains a mixture of re-ligated original fragments and the chimeric ligation products of interest. In the original 3C protocol, interaction frequency is measured using quantitative PCR (qPCR) with primers designed to specifically amplify the junction between two predetermined genomic loci. The quantity of PCR product is directly proportional to the frequency with which those two loci interacted in the original cell population [21].

Key Research Reagents and Solutions

The successful execution of the 3C protocol relies on a suite of specific reagents, each with a critical function.

Table 1: Essential Reagents for 3C Protocol

| Reagent | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Formaldehyde | Cross-linking agent that covalently fixes protein-DNA and protein-protein interactions in place. | Standardization is critical; over-cross-linking can create insoluble aggregates [1]. |

| Restriction Enzyme | Digests cross-linked chromatin to generate defined DNA fragments with compatible ends for ligation. | Choice (e.g., HindIII, DpnII) determines resolution and potential bias [21]. |

| DNA Ligase | Joins cross-linked DNA fragments, creating the chimeric molecules that represent spatial contacts. | Performed under extreme dilution to favor intramolecular ligation [1] [21]. |

| Proteinase K | Reverses cross-links by digesting proteins, freeing the DNA for subsequent analysis. | Ensves complete reversal of crosslinks for accurate PCR quantification [21]. |

| Locus-Specific Primers | Amplify specific chimeric ligation products for quantification via qPCR. | Design is critical for specificity and efficiency in the original 3C method [21]. |

Evolution of the 3C Technology Family

The original 3C method is a powerful "one-vs-one" hypothesis-testing tool. However, its low throughput spurred the development of advanced derivatives that leverage next-generation sequencing to answer broader biological questions.

Table 2: The 3C Technology Family: From Targeted to Genome-Wide

| Technology | Interrogation Scope | Core Principle | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3C | One-vs-One | qPCR quantification of a single, predefined interaction. | Hypothesis testing of specific chromatin loops (e.g., enhancer-promoter) [1] [21]. |

| 4C | One-vs-All | Inverse PCR from a single "bait" locus, followed by sequencing. | Unbiased discovery of all interacting partners of a known locus [1] [21]. |

| 5C | Many-vs-Many | Multiplexed ligation-mediated amplification for a targeted genomic region. | Creating high-resolution interaction matrices of large, complex loci [1] [21]. |

| Hi-C | All-vs-All | Incorporates a biotinylation step to purify ligation junctions before genome-wide sequencing. | Unbiased, genome-wide mapping of chromatin interactions and overall nuclear architecture [1] [21]. |

| ChIA-PET | Protein-Centric All-vs-All | Combines chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) with a 3C-style ligation. | Mapping long-range interactions mediated by a specific protein (e.g., CTCF, RNA Pol II) [21]. |

The relationships and evolution of these methods are summarized in the following diagram:

Application in Drug Discovery and Development

The ability to map the 3D genome has profound implications for understanding disease mechanisms and identifying novel therapeutic targets, particularly for complex conditions like cardiovascular diseases and cancer.

Identifying Novel Therapeutic Targets

Alterations in the three-dimensional chromatin structure have been shown to regulate gene expression and directly influence disease onset and progression [22]. Hi-C technology enables the unbiased discovery of these disease-relevant structural variants and the non-coding regulatory elements they affect.

- Heart Failure: Hi-C analysis of cardiomyocytes has revealed that a comprehensive restructuring of chromatin architecture is a primary driver of heart failure. Studies using mice with targeted deletion of the chromatin architect protein CTCF showed that disruption of topologically associating domains (TADs) leads to widespread changes in gene expression and heart failure phenotypes [22].

- Cancer and Developmental Disorders: Chromosomal rearrangements, common in cancers, can catastrophically rewire the 3D genome. For example, the translocation of a potent enhancer near a proto-oncogene or the breakdown of a TAD boundary can lead to aberrant oncogene expression and tumorigenesis [1]. Mapping these structural changes provides invaluable insights into novel mechanisms of pathogenesis.

Informing Clinical Trial Design

The discovery of targets through 3D genomics can directly feed into the drug development pipeline, influencing early-stage clinical trials. As per FDA guidance, protocols for Phase 1 trials must specify in detail all elements critical to safety, including toxicity monitoring and dose adjustment rules [23]. When a novel target is identified through Hi-C, the initial clinical protocols must be designed with consideration of:

- The background risks associated with the disease.

- Previous knowledge of toxicities from animal studies.

- The mechanistic role of the target, as revealed by its position in the 3D regulatory network [23] [22].

Supporting Computational Approaches

The data generated from 3C and Hi-C experiments are invaluable for computational tools in drug design. For instance, molecular docking—a key method in structure-based drug design—explores the conformations of small-molecule ligands within the binding sites of macromolecular targets [24]. While traditionally used for protein-ligand interactions, the principles of conformational search and binding free energy estimation are being adapted to understand the protein-DNA interactions that govern 3D genome folding. Furthermore, simulators like Sim3C have been developed to model Hi-C sequencing data, providing a means to test analysis algorithms and optimize experimental parameters before costly wet-lab experiments are conducted [25].

The genetic material within the cell nucleus is not randomly organized but is folded into a highly sophisticated three-dimensional architecture. This spatial arrangement is now widely recognized as a crucial epigenetic layer that governs fundamental nuclear processes, including gene regulation, DNA replication, and repair, thereby ensuring genome stability [26] [21]. The hierarchical organization of chromatin facilitates and constrains biological functions, creating a dynamic structural framework that responds to cellular signals and maintains genomic integrity [27] [28].

Understanding this architecture has been revolutionized by the development of Chromosome Conformation Capture (3C) and its derivative technologies, particularly Hi-C (High-throughput Chromosome Conformation Capture) [29] [21]. These molecular techniques have transitioned nuclear organization studies from microscopic observations of individual loci to genome-wide, high-resolution interaction maps, enabling researchers to systematically decipher the principles linking spatial genome organization to its function [26] [30]. This document details how the 3D genome structure regulates gene expression and stability, framed within the context of Hi-C and 3C-based research methodologies.

Hierarchical Organization of the 3D Genome

The genome is packaged into a series of interdependent structural layers. The following table summarizes the key organizational levels and their functional roles [27] [28].

Table 1: Hierarchical Levels of 3D Genome Organization and Their Functions

| Structural Level | Spatial Scale | Key Features | Functional Role in Gene Regulation & Stability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromosome Territories (CTs) | Whole Chromosomes | Distinct, non-overlapping nuclear regions for each chromosome [26] [27]. | Establishes a basal organization; positioning of genes within the territory can influence their activity [21]. |

| A/B Compartments | Multi-Megabase | A Compartments: Gene-rich, transcriptionally active, open chromatin (euchromatin) [27] [28].B Compartments: Gene-poor, transcriptionally inactive, compact chromatin (heterochromatin) [27] [28]. | Segregates active and inactive chromatin, creating functional nuclear environments. The A compartment is associated with early DNA replication, while the B compartment replicates later [28]. |

| Topologically Associating Domains (TADs) | ~100 kb - 1 Mb | Self-interacting domains with sharp boundaries, conserved across cell types [27]. Boundaries are enriched for CTCF and cohesin [27] [28]. | Acts as the fundamental regulatory unit, constraining interactions between regulatory elements (like enhancers) and their target genes within a domain, ensuring precise gene expression [27] [28]. |

| Chromatin Loops | ~10 kb - 1 Mb | Ring-like structures formed by protein-mediated interactions, often between promoters and enhancers [27]. | Directly brings distal regulatory elements into physical proximity with gene promoters to activate or repress transcription [27] [21]. |

Figure 1: Hierarchy of 3D Genome Organization. Chromatin loops form the base of TADs, which are organized into larger A/B compartments that make up chromosome territories.

Mechanisms of Gene Regulation by 3D Architecture

Facilitation of Enhancer-Promoter Communication

The primary mechanism by which 3D structure regulates gene expression is by orchestrating spatial encounters between gene promoters and their distal regulatory elements, particularly enhancers [27]. Although these elements can be linearly distant on the chromosome, chromatin looping within TADs brings them into close physical proximity, enabling the enhancer to activate transcription [27] [21]. This process is often mediated by the cooperative action of the architectural proteins CTCF and cohesin, which facilitate loop extrusion and stabilize these interactions [27]. This spatial selectivity ensures that enhancers activate only their appropriate target genes and not others outside the TAD, providing precision in transcriptional control.

Compartmentalization of Chromatin States

The segregation of the genome into A and B compartments creates distinct functional nuclear environments [28]. The transcriptionally active A compartment, enriched with open chromatin and activating histone marks like H3K27ac, is conducive to gene expression. In contrast, the B compartment, characterized by repressive marks and compact heterochromatin, silences genes [27]. The dynamic transition of a genomic region from the B to the A compartment is often associated with gene activation, and vice-versa [31]. This large-scale compartmentalization provides a robust structural framework that reinforces cellular identity and gene expression programs.

3D Genome Architecture and Genome Stability

TADs as Guardians of Genomic Integrity

TAD boundaries function as insulators that prevent aberrant interactions between different regulatory domains [27]. The disruption of TAD boundaries—through genetic deletion, inversion, or epigenetic silencing of CTCF binding sites—can lead to ectopic enhancer-promoter interactions [27] [31]. This miscommunication can cause misexpression of genes, which is a known mechanism in developmental disorders and cancers such as congenital limb malformations and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) [27]. Thus, intact TAD structure is crucial for isolating genomic neighborhoods and preventing pathogenic gene activation.

Role in DNA Repair and Replication

The 3D genome organization is intimately linked to the cellular DNA damage response. TADs can constrain the spread of DNA damage signaling factors, helping to localize the repair machinery to the site of a DNA double-strand break (DSB) [28]. Furthermore, the spatial organization of the genome influences DNA replication timing. The A compartment is generally replicated in early S-phase, while the B compartment is replicated later [28]. TAD boundaries are often enriched for replication origins, and the replication process itself can cause a temporary reduction in the insulation strength of these boundaries, indicating a dynamic interplay between 3D structure and DNA synthesis [28].

The discovery of the principles of 3D genome organization has been driven by the development and application of 3C-based methods. The following table compares the key technologies in this family [21].

Table 2: Comparison of Chromosome Conformation Capture (3C) Technologies

| Technique | Acronym Resolution | Principle | Key Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3C | One-to-one | Analyzes interaction frequency between two specific, pre-defined loci using PCR [30] [21]. | Validating specific chromatin loops (e.g., enhancer-promoter) [21]. | Low throughput; requires prior knowledge of potential interacting regions [21]. |

| 4C | One-to-all | Identifies all genomic regions interacting with a single, pre-defined "viewpoint" locus using inverse PCR [21]. | Mapping the global interaction partners of a specific gene or regulatory element [21]. | Viewpoint-specific; can miss local interactions [30]. |

| 5C | Many-to-many | Detects multiplex interactions within a targeted genomic region using a large pool of primers [21]. | Analyzing the spatial architecture of a specific locus, such as a gene cluster [21]. | Limited to targeted regions; primer design can be complex [21]. |

| Hi-C | All-to-all | Captures genome-wide interaction frequencies by incorporating biotinylated nucleotides during ligation and purifying chimeric junctions [29] [21]. | Unbiased discovery of A/B compartments, TADs, and chromatin loops across the entire genome [29] [32]. | Requires high sequencing depth; complex data analysis [29]. |

| ChIA-PET | Protein-centric | Combines Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) with a 3C-style ligation to map interactions bound by a specific protein [21]. | Identifying long-range interactions mediated by a protein of interest (e.g., CTCF, RNA Pol II) [21]. | Dependent on antibody quality and efficiency. |

Detailed Hi-C Protocol

The Hi-C protocol is the cornerstone of modern 3D genomics. The following workflow outlines the key steps for generating a Hi-C library [29].

Figure 2: Hi-C Experimental Workflow. Key steps include crosslinking, digestion, biotinylation, ligation, and library preparation for sequencing.

- Crosslinking: Cells are treated with formaldehyde to create covalent bonds between spatially proximate DNA fragments and the proteins that bridge them, effectively "freezing" the 3D chromatin structure [29].

- Cell Lysis and Restriction Digest: Cells are lysed, and chromatin is digested with a frequent-cutting restriction enzyme (e.g., DpnII or HindIII). This fragments the DNA, leaving sticky ends [29].

- Biotinylation and Ligation: The sticky ends are filled in with nucleotides, including a biotinylated residue. Under highly diluted conditions, the digested ends are ligated, which preferentially joins crosslinked fragments. This creates chimeric DNA molecules representing spatial interactions [29].

- Reverse Crosslinking and DNA Purification: The crosslinks are reversed, and proteins are degraded, releasing the DNA. The biotinylated ligation products are purified away from non-ligated fragments [29].

- Shearing and Biotin Pull-Down: The DNA is sheared to a size suitable for sequencing. Biotin-marked fragments (the true ligation junctions) are isolated using streptavidin-coated magnetic beads [29].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: A standard sequencing library is prepared from the purified fragments and subjected to high-throughput paired-end sequencing [29].

The resulting data is processed using bioinformatic tools to generate contact matrices, which are then analyzed to identify compartments, TADs, and specific loops.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Hi-C

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Hi-C Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Formaldehyde | Crosslinking agent that fixes protein-DNA and DNA-DNA interactions in place [29]. |

| Restriction Enzyme (e.g., DpnII, HindIII) | Digests crosslinked chromatin into fragments, defining the potential resolution of the Hi-C experiment [29]. |

| Biotin-dATP / Biotin-dCTP | Biotinylated nucleotides used to label the ends of digested fragments, enabling selective purification of valid ligation junctions [29]. |

| Streptavidin Magnetic Beads | Used to capture and purify the biotinylated ligation products, crucial for enriching the library for meaningful interaction data [29]. |

| Antibodies for ChIA-PET (e.g., anti-CTCF) | For protein-centric methods like ChIA-PET, specific antibodies are used to immunoprecipitate the protein of interest and its bound DNA fragments [21]. |

Applications in Disease and Drug Development

Hi-C technologies are increasingly applied to understand disease mechanisms and identify novel therapeutic targets. In cardiovascular research, Hi-C has revealed how alterations in chromatin loops and TADs contribute to diseases like heart failure and congenital heart disease [31]. For example, in dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), overexpression of the transcription factor HAND1 leads to widespread chromatin reprogramming and increased enhancer-promoter interactions, causing transcriptional dysregulation [27].

In oncology, Hi-C has uncovered how the 3D genome is rewired in cancer cells. In acute myeloid leukemia (AML), hypermethylation of CTCF binding sites leads to loss of TAD insulation and aberrant chromatin interactions, driving leukemogenesis [27]. Similarly, studies in colorectal cancer have shown reorganization of A/B/I compartments that can either suppress or promote tumor progression [27]. By mapping these structural variants and epigenetic changes, researchers can pinpoint dysregulated genes and pathways that may serve as targets for epigenetic therapies or novel drug development efforts.

3C Technology Toolkit: From Basic 3C to Advanced Capture Hi-C and Real-World Applications

The genome of a eukaryotic cell presents a profound paradox of scale and function. The human genome, comprising approximately two meters of DNA, must be efficiently compacted into a nucleus that is often less than 10 micrometers in diameter—a feat analogous to packing 40 kilometers of fine thread into a tennis ball [1]. For decades, our understanding of the genome was largely confined to its one-dimensional sequence of nucleotides. However, it is now unequivocally clear that this compaction is not a random entanglement but a highly sophisticated and dynamic architectural process essential for fundamental cellular operations like gene expression, DNA replication, and repair [1]. This spatial organization creates a critical regulatory layer, enabling distant genomic elements, such as enhancers and promoters, to come into close physical proximity to control gene expression [1] [15]. The realization that genome function is inextricably linked to its spatial organization launched a new era in genomics, driven by the development of the Chromosome Conformation Capture (3C) method and its derivatives [1].

The Foundational Principle of Chromosome Conformation Capture

At the heart of the entire C-series technologies lies an elegant core principle: converting the physical property of spatial proximity within the nucleus into a stable, quantifiable DNA molecule [1]. First described in 2002 by Dekker et al., the foundational 3C method provided a powerful new logic to answer a seemingly simple question: do two genomic regions that are distant in the linear sequence physically interact within the 3D space of the nucleus? [3] [33] This is achieved by "freezing" chromatin interactions in place with formaldehyde cross-linking, digesting the DNA with a restriction enzyme, and then performing ligation under diluted conditions that favor the joining of cross-linked (and thus spatially proximal) fragments [1] [34]. The resulting chimeric DNA molecules provide a permanent, linear record of transient 3D interactions, forming the basis for all subsequent, higher-throughput methods [1].

Core Workflow of 3C-Based Methods

The standard workflow for 3C-based techniques involves several key steps [1] [34] [21]:

- In Vivo Cross-linking: Cells are treated with formaldehyde, which creates covalent protein-DNA and protein-protein cross-links, effectively "snap-freezing" the chromatin in its native 3D conformation [1].

- Chromatin Fragmentation: Cells are lysed, and the cross-linked chromatin is digested with a restriction enzyme (e.g., HindIII, DpnII) that cuts DNA at specific recognition sites [1] [34].

- Proximity Ligation: The digested chromatin is subjected to ligation under highly diluted conditions. This favors intramolecular ligation between DNA fragments held together by cross-links, meaning only fragments that were originally close in 3D space are ligated [1] [33].

- Purification and Analysis: Cross-links are reversed, and the DNA is purified. The resulting library of ligation products is then analyzed using methods specific to each 3C-variant, such as PCR, microarray, or high-throughput sequencing [1] [21].

The 3C Technology Family: A Comparative Guide

The evolution of the C-method family represents a direct response to the expanding scope of scientific inquiry, progressing from targeted hypothesis testing to unbiased, genome-wide discovery [1]. The techniques are systematically classified based on the scope of interactions they interrogate.

Table 1: Classification and Scope of 3C-Based Technologies

| Technology | Interaction Scope | Core Principle | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3C (Chromosome Conformation Capture) | One-vs-One [1] [3] | Quantitative PCR with locus-specific primers [1] [21] | Hypothesis-driven testing of interaction between two specific, pre-defined loci (e.g., an enhancer and its candidate promoter) [1]. |

| 4C (Chromosome Conformation Capture-on-Chip/Circularized 3C) | One-vs-All [1] [3] | Inverse PCR with primers for a single "bait" or "viewpoint" locus, combined with sequencing or microarrays [1] [21]. | Unbiased discovery of all genomic regions interacting with a single, predefined locus of interest [1]. |

| 5C (Chromosome Conformation Capture Carbon Copy) | Many-vs-Many [1] [3] | Multiplexed ligation-mediated amplification with pools of primers [1] [21]. | High-throughput mapping of all interactions within a large, contiguous genomic region (e.g., a gene cluster) [1]. |

| Hi-C (High-Throughput Chromosome Conformation Capture) | All-vs-All [1] [3] | Ligation of biotin-labeled fragments and pull-down, paired with high-throughput sequencing [34] [35]. | Unbiased, genome-wide profiling of all possible chromatin interactions and the global 3D architecture of the genome [1] [34]. |

The following diagram illustrates the core conceptual difference between these four main 3C-based methods:

Detailed Methodologies and Protocols

3C (One-vs-One): Targeted Interaction Analysis

The original 3C method is a hypothesis-driven tool for quantifying the interaction frequency between two specific genomic loci [1] [21].

Protocol Summary:

- Cross-linking & Lysis: Cells are cross-linked with formaldehyde (e.g., 1-3% for 10-30 minutes). After quenching with glycine, cells are lysed to isolate nuclei [1] [33].

- Restriction Digest: Chromatin is digested to completion with a frequent-cutter restriction enzyme (e.g., HindIII, DpnII) [1] [21]. Digestion efficiency must be monitored, as incomplete digestion introduces significant bias.