A Comprehensive Guide to ChIP-seq for Histone Modification Analysis: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) for mapping histone modifications, a critical technology in epigenomics.

A Comprehensive Guide to ChIP-seq for Histone Modification Analysis: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) for mapping histone modifications, a critical technology in epigenomics. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of histone biology and the role of post-translational modifications in gene regulation and disease. The guide details robust experimental protocols, from chromatin preparation and immunoprecipitation to library construction and high-throughput sequencing, incorporating established standards from consortia like ENCODE. It further addresses common troubleshooting scenarios and optimization strategies for challenging samples, including low-input protocols. Finally, it explores rigorous data analysis methods for peak calling, differential analysis, and validation, empowering readers to generate high-quality, biologically relevant epigenomic data for both basic research and clinical translation.

Understanding Histone Modifications and the Power of ChIP-seq

Histone post-translational modifications (PTMs) represent a fundamental epigenetic mechanism that regulates gene expression and chromatin structure in eukaryotes, playing pivotal roles in various cellular processes including transcriptional regulation, DNA repair, and genome stability [1]. These chemical modifications on histone tails—such as methylation, acetylation, and phosphorylation—encode epigenetic information that can be inherited through cell divisions, forming a critical layer of transcriptional control beyond the DNA sequence itself [2]. Specific histone PTMs create binding sites for downstream effector proteins containing specialized domains like bromodomains, chromodomains, and Tudor domains, which in turn recruit chromatin remodeling complexes, transcriptional activators or repressors, and DNA repair factors to modulate gene expression and cellular processes [1]. The complex interactions between different PTMs, a phenomenon known as histone crosstalk, serve as a sophisticated code for orchestrating chromatin-templated functions [1].

The functional consequences of histone PTMs depend on both the specific modified residue and the type of modification. For instance, histone methylation can have either activating or repressive effects depending on the position of the methylated residues and the degree of methylation [1]. Tri-methylation of histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4me3) is generally associated with active transcription and is considered a hallmark of euchromatic regions, while trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 9 and 27 (H3K9me3 and H3K27me3) represent repressive marks associated with constitutive and facultative heterochromatin, respectively [1]. These modifications are catalyzed by specific families of histone lysine methyltransferases (KMTs), with H3K4me2/3 catalyzed by the KMT2 family, H3K9me3 by the KMT1 family, and H3K27me3 by the KMT6 family [1]. These enzymes often function as part of multi-protein complexes, such as COMPASS for KMT2 and PRC2 (Polycomb Repressive Complex 2) for KMT6, providing regulatory specificity and functional diversity [1].

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Followed by Sequencing (ChIP-seq): An Essential Tool for Epigenetic Research

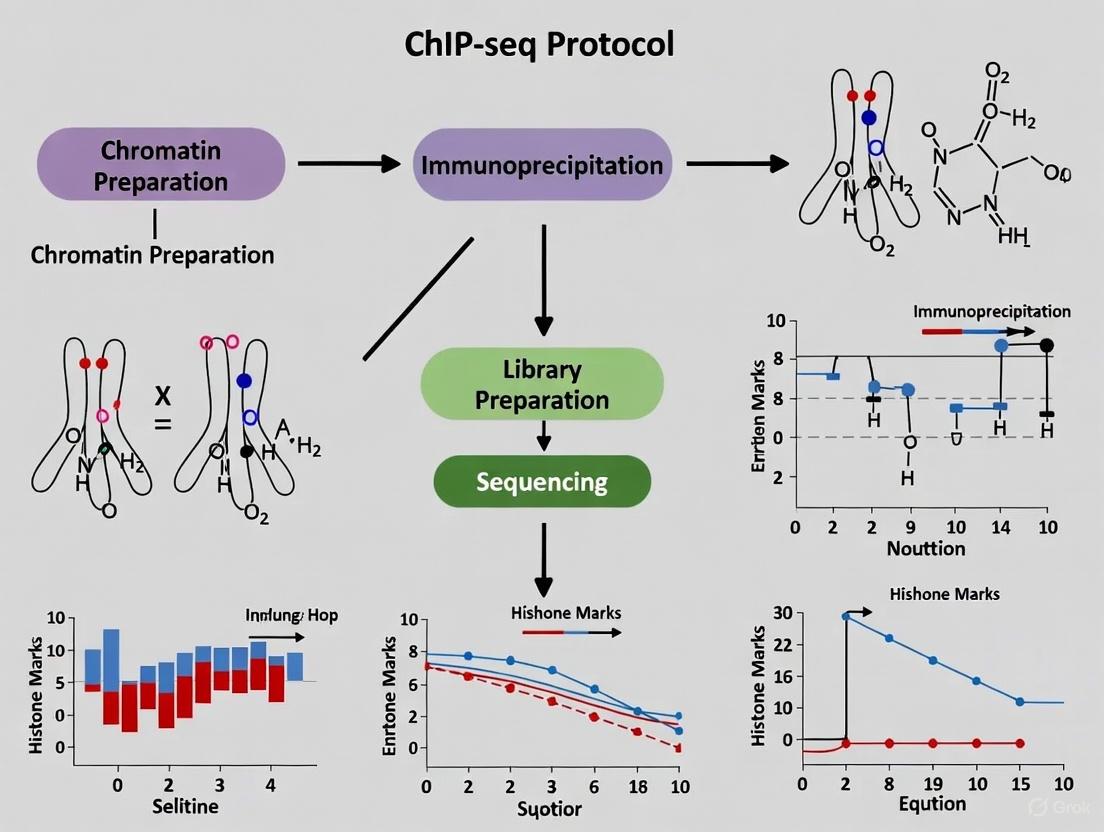

Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) has emerged as a central method in epigenomic research for mapping protein-DNA interactions and histone modifications across the genome [3] [4]. This powerful technique combines chromatin immunoprecipitation with high-throughput DNA sequencing to identify the genomic binding sites of DNA-associated proteins, providing crucial insights into the epigenomic landscape that contributes to cell identity, development, lineage specification, and disease [3]. The basic ChIP-seq procedure involves several critical steps: (1) chemical cross-linking of proteins to DNA using formaldehyde; (2) cell disruption and chromatin fragmentation to target sizes of 100-300 bp via sonication or enzymatic digestion; (3) immunoprecipitation of the protein of interest with its bound DNA using specific antibodies; (4) reversal of cross-links and purification of enriched DNA; and (5) preparation and sequencing of the DNA library [5]. The resulting sequencing data allows researchers to map the genomic locations of histone modifications with nucleotide-level resolution, enabling systematic analysis of how the epigenomic landscape contributes to various biological processes and disease states.

The ENCODE consortium has developed specialized analysis pipelines for different classes of protein-chromatin interactions, with the histone ChIP-seq pipeline specifically designed for proteins that associate with DNA over longer regions or domains, such as histone proteins and specific post-translational histone modifications [6]. This pipeline can resolve both punctate binding and longer chromatin domains bound by many instances of the target protein or modification, with outputs suitable as input to chromatin segmentation models that classify chromatin regions into functional categories [6]. The quality of a ChIP experiment is governed by multiple factors, with antibody specificity and the degree of enrichment achieved in the immunoprecipitation step being particularly critical [5]. The ENCODE guidelines therefore mandate rigorous antibody validation, including primary characterization by immunoblot analysis or immunofluorescence and secondary tests to confirm specificity and functionality in ChIP experiments [5].

Table 1: Key Histone Modifications and Their Functional Associations

| Histone Mark | Chromatin Association | Transcriptional Impact | Catalytic Enzyme Complex |

|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 | Euchromatin | Activating | COMPASS (KMT2 family) |

| H3K27ac | Euchromatin | Activating | - |

| H3K27me3 | Facultative Heterochromatin | Repressive | PRC2 (KMT6 family) |

| H3K9me3 | Constitutive Heterochromatin | Repressive | KMT1 family |

| H3K36me3 | Gene Bodies | Elongation-Associated | - |

| H3K4me1 | Enhancers/Promoters | Priming/Activating | - |

Experimental Design and Quality Control Standards

The ENCODE consortium has established comprehensive guidelines and quality metrics for ChIP-seq experiments to ensure data reliability and reproducibility [6] [5]. For histone ChIP-seq, experiments should ideally include two or more biological replicates, either isogenic or anisogenic, with exemptions granted only in special circumstances such as assays using EN-TEx samples where experimental material is limited [6]. Each ChIP-seq experiment must include a corresponding input control experiment with matching run type, read length, and replicate structure to control for technical artifacts and background signal [6]. Library complexity is rigorously assessed using multiple metrics including the Non-Redundant Fraction (NRF) and PCR Bottlenecking Coefficients 1 and 2 (PBC1 and PBC2), with preferred values of NRF > 0.9, PBC1 > 0.9, and PBC2 > 10 indicating high-quality libraries with sufficient complexity [6].

Sequencing depth requirements vary depending on the specific histone mark being investigated. For narrow histone marks such as H3K4me3 and H3K9ac, each replicate should contain at least 20 million usable fragments, while for broad histone marks including H3K27me3 and H3K36me3, each replicate requires a minimum of 45 million usable fragments to ensure comprehensive coverage [6]. The exception to these standards is H3K9me3, which presents unique challenges due to its enrichment in repetitive regions of the genome; in tissues and primary cells, H3K9me3 experiments should target 45 million total mapped reads per replicate to adequately capture peaks in non-repetitive regions [6]. Additional technical requirements specify that read length should be a minimum of 50 base pairs, though longer reads are encouraged, and pipeline files must be mapped to standard reference genomes such as GRCh38 for human or mm10 for mouse samples [6].

Advanced Applications and Research Findings

Histone Modification Interplay in Fungal Pathogens

Recent research in the phytopathogenic fungus Pyricularia oryzae has provided remarkable insights into the complex interplay between different histone modifications [1]. Through ChIP-seq analysis of knock-out mutants lacking enzymes responsible for H3K4me2/3, H3K9me3, or H3K27me3, researchers discovered that loss of specific PTMs leads to significant alterations in other modifications, demonstrating extensive crosstalk between different epigenetic marks [1]. This study defined distinct genomic compartments based on histone modification patterns: euchromatin (EC) marked by H3K4me2-rich segments, constitutive heterochromatin (cHC) marked by H3K9me3-rich segments, and facultative heterochromatin (fHC) marked by H3K27me3-rich segments [1]. Surprisingly, the research identified two distinct subcompartments within facultative heterochromatin: K4-fHC (adjacent to euchromatin) and K9-fHC (adjacent to constitutive heterochromatin) [1].

These facultative heterochromatin subcompartments exhibit distinct functional properties despite sharing the H3K27me3 mark. Both contain poorly conserved genes, but K9-fHC harbors more transposable elements, while K4-fHC is more enriched for genes upregulated during infection, including effector-like genes that facilitate host-pathogen interactions [1]. Furthermore, H3K27me3 levels in K4-fHC respond to changes in other PTMs, especially H3K9me3, and to environmental conditions, suggesting that K4-fHC functions as a reservoir of genes highly responsive to chromatin context and environmental cues [1]. This compartmental specialization illustrates how the combinatorial patterns of histone modifications create functionally distinct chromatin environments that regulate specific genomic functions and response capacities.

Evolutionary Conservation of H3K27me3 Function

Investigations into the closest living relatives of animals, choanoflagellates, have revealed deep evolutionary conservation of H3K27me3 function [7]. In the model choanoflagellate Salpingoeca rosetta, chromatin profiling demonstrated that H3K27me3 decorates genes with cell type-specific expression, mirroring its role in animal development where it represses lineage-specific genes in cell types where they should not be expressed [7]. Remarkably, H3K27me3 also marks LTR retrotransposons in these organisms, retaining a potential ancestral role in transposable element repression that predates the emergence of animal multicellularity [7]. These findings support the emergence of gene-associated histone modification states that underpin development before the evolution of animal multicellularity, providing important insights into the evolutionary history of epigenetic regulation.

The study further uncovered a putative bivalent chromatin state at cell type-specific genes consisting of both H3K27me3 and H3K4me1, suggesting that the capacity for epigenetic priming of gene expression states arose early in holozoan evolution [7]. This bivalent state parallels similar configurations observed in embryonic stem cells, where key developmental genes simultaneously carry activating and repressing marks, keeping them poised for future activation while maintaining transcriptional silence until the appropriate developmental cue [7]. The conservation of these regulatory mechanisms across vast evolutionary timescales highlights the fundamental importance of histone modifications in enabling complex gene regulatory programs.

Table 2: Genomic Compartments Identified in Pyricularia oryzae

| Compartment | Defining Mark | Gene Content | Functional Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Euchromatin (EC) | H3K4me2-rich | 3285 genes (26.9%) | Active transcription |

| Constitutive Heterochromatin (cHC) | H3K9me3-rich | 68 genes (0.6%) | Stable silencing, TE-rich |

| Facultative Heterochromatin (fHC) | H3K27me3-rich | 2313 genes (20.2%) | Conditionally silenced |

| K4-fHC subcompartment | H3K27me3, adjacent to EC | Infection-responsive genes | Environmentally responsive |

| K9-fHC subcompartment | H3K27me3, adjacent to cHC | TE-enriched | Stable repression |

Single-Cell Multi-Omic Epigenetic Profiling

Recent technological advances have enabled simultaneous detection of DNA methylation and histone modifications at single-cell resolution, opening new frontiers in epigenetic research [2]. The novel scEpi2-seq method achieves joint readout of histone modifications and DNA methylation in single cells by leveraging TET-assisted pyridine borane sequencing (TAPS) combined with antibody-directed profiling of histone marks [2]. This technique provides a multi-omic readout at the single-cell and single-molecule level, revealing how DNA methylation maintenance is influenced by local chromatin context and how different epigenetic layers interact during cell type specification [2].

Application of scEpi2-seq has demonstrated distinct relationships between specific histone modifications and DNA methylation patterns. Regions marked by repressive histone modifications H3K27me3 and H3K9me3 show much lower DNA methylation levels (8-10%) compared to regions marked by the active mark H3K36me3 (50%) [2]. These findings highlight the complex interplay between different epigenetic layers and demonstrate how histone modification patterns influence DNA methylation distributions across the genome. The ability to profile multiple epigenetic modalities simultaneously in single cells provides unprecedented insights into epigenetic heterogeneity within cell populations and the dynamics of epigenomic maintenance during cellular differentiation and lineage commitment.

Protocols and Methodologies

Histone ChIP-seq Experimental Protocol

The ENCODE consortium has established standardized protocols for histone ChIP-seq experiments to ensure reproducibility and data quality across different laboratories and studies [6] [5]. The following detailed protocol outlines the key steps for successful histone modification mapping:

Cell Fixation and Cross-linking: Begin by treating cells or tissues with 1% formaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature to cross-link proteins to DNA. Quench the cross-linking reaction by adding glycine to a final concentration of 0.125 M. Wash cells twice with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) [5].

Cell Lysis and Chromatin Preparation: Resuspend cell pellets in cell lysis buffer (5 mM PIPES pH 8.0, 85 mM KCl, 0.5% NP-40) supplemented with protease inhibitors and incubate on ice for 10 minutes. Pellet nuclei by centrifugation and resuspend in nuclear lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl pH 8.1, 10 mM EDTA, 1% SDS) with protease inhibitors. Incubate on ice for 10 minutes [5].

Chromatin Fragmentation: Shear chromatin to an average size of 200-500 bp using a sonicator. Optimal shearing conditions must be determined empirically for each cell type and sonicator. Centrifuge the sheared chromatin at 20,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C to remove insoluble material [5].

Immunoprecipitation: Pre-clear the chromatin supernatant with protein A or protein G magnetic beads for 1 hour at 4°C. Incubate the pre-cleared chromatin with validated, target-specific antibody overnight at 4°C with rotation. The following day, add protein A or protein G magnetic beads and incubate for 2 hours at 4°C with rotation [5].

Washing and Elution: Wash beads sequentially with low salt wash buffer (0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.1, 150 mM NaCl), high salt wash buffer (0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.1, 500 mM NaCl), LiCl wash buffer (0.25 M LiCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.1), and finally TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA). Elute chromatin from beads with elution buffer (1% SDS, 0.1 M NaHCO3) [5].

Reverse Cross-linking and DNA Purification: Reverse cross-links by adding NaCl to a final concentration of 0.2 M and incubating at 65°C for 4 hours or overnight. Digest RNA with RNase A and proteins with proteinase K. Purify DNA using phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation or silica membrane-based purification kits [5].

Library Preparation and Sequencing: Prepare sequencing libraries using commercial library preparation kits following manufacturer's instructions. Assess library quality using bioanalyzer or tape station and quantify by qPCR. Sequence libraries on an appropriate high-throughput sequencing platform to achieve the recommended depth for the specific histone mark being investigated [6].

Computational Analysis Workflow

The computational analysis of histone ChIP-seq data involves multiple steps to transform raw sequencing reads into interpretable genomic information:

Quality Control and Preprocessing: Begin by assessing raw read quality using FastQC [4]. Remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases using Trimmomatic with parameters "SLIDINGWINDOW:4:10 MINLEN:20" [4]. Verify quality improvement by running FastQC on trimmed reads.

Read Alignment and Processing: Align cleaned reads to the appropriate reference genome (e.g., GRCh38, mm10) using BWA-MEM with default parameters [4]. Convert SAM files to BAM format, sort, and index using Samtools. For visualization, generate BigWig signal tracks from BAM files using DeepTools with parameters "--extendReads 200 --binSize 5 --normalizeUsing None" to create normalized coverage profiles [4].

Peak Calling and Annotation: Perform peak calling using HOMER's findPeaks command with style parameters appropriate for histone marks ("histone" for broad marks, "factor" for narrow marks) and a false discovery rate (FDR) threshold typically set at 0.001 [4]. Annotate peaks with genomic features using HOMER's annotatePeaks.pl script, specifying promoter regions as needed [4].

Downstream Analysis: Conduct motif enrichment analysis using HOMER's findMotifsGenome.pl with parameters "-size 200 -len 8,10,12" to identify enriched transcription factor binding sites [4]. Generate quality control metrics including library complexity measures (NRF, PBC1, PBC2), FRiP scores, and reproducibility measures between replicates.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Histone ChIP-seq Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Function | Quality Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specific Antibodies | Validated for ChIP-seq; lot-specific characterization | Target immunoprecipitation | Immunoblot showing >50% signal in main band; reduced signal in knockout controls |

| Protein A/G Magnetic Beads | High-binding capacity, low non-specific binding | Antibody-target complex capture | Minimal background in control IPs |

| Cross-linking Reagent | High-purity formaldehyde | Protein-DNA cross-linking | Freshly prepared, <6 months old |

| Chromatin Shearing Reagents | Sonication shearing kit or enzymatic shearing kit | DNA fragmentation to 100-500 bp | Post-shearing size verification |

| DNA Purification Kit | Silica membrane or phenol-chloroform | Purification of immunoprecipitated DNA | High recovery, minimal inhibitor carryover |

| Library Preparation Kit | Illumina-compatible with dual indexing | Sequencing library construction | Low duplicate rates, high complexity |

| Quality Control Instruments | Bioanalyzer/TapeStation, qPCR | Library quality assessment | RIN >8, distinct size distribution |

Automated Analysis Platforms

For researchers without extensive bioinformatics expertise, several automated platforms streamline ChIP-seq data analysis. The H3NGST (Hybrid, High-throughput, and High-resolution NGS Toolkit) platform provides a fully automated, web-based solution for end-to-end ChIP-seq analysis [4]. This system requires only a BioProject accession number (e.g., PRJNA, SRX, GSM, GEO) and performs comprehensive analysis including raw data retrieval via BioProject ID, quality control, adapter trimming, reference genome alignment, peak calling, and genomic annotation [4]. The platform automatically detects library layout (single-end or paired-end) and dynamically adjusts parameters based on dataset characteristics, making sophisticated analysis accessible to non-specialist users while maintaining data security through SSL/TLS encrypted processing [4].

Alternative platforms such as Galaxy, GenePattern, and Cistrome Galaxy offer varying degrees of web-based functionality but typically require manual data uploads, user registration, or local software installation [4]. The commercial Basepair service provides similar automated analysis capabilities. When selecting an analysis platform, researchers should consider their computational resources, technical expertise, data security requirements, and the need for customization in analysis parameters.

Histone post-translational modifications represent a crucial layer of epigenetic regulation that controls chromatin structure and gene expression patterns across diverse biological contexts. The development of ChIP-seq methodologies has revolutionized our ability to map these modifications genome-wide, providing unprecedented insights into their distribution, dynamics, and functional consequences. Standardized experimental protocols and analysis pipelines, such as those established by the ENCODE consortium, ensure the generation of high-quality, reproducible data that can be compared across studies and integrated with other genomic datasets. Recent advances, including single-cell multi-omic technologies and automated analysis platforms, continue to expand the frontiers of epigenetic research, enabling increasingly sophisticated investigations into the complex interplay between different epigenetic marks and their collective role in shaping gene expression programs. As these methodologies continue to evolve, they will undoubtedly yield further insights into how histone modifications contribute to normal development, disease pathogenesis, and therapeutic responses.

Histone modifications represent a crucial layer of epigenetic regulation that controls chromatin structure and gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence. These post-translational modifications occur on the N-terminal tails of histone proteins that protrude from the nucleosome core particle, the fundamental repeating unit of chromatin consisting of DNA wrapped around an octamer of core histones (H2A, H2B, H3, and H4) [8] [9]. The "histone code" hypothesis proposes that specific combinations of these modifications create a recognizable language that is interpreted by cellular machinery to determine transcriptional outcomes [8] [10]. These modifications function through two primary mechanisms: by altering the electrostatic charge of histones to directly influence chromatin compaction, or by creating binding sites for reader proteins that execute downstream functions [9] [11]. The dynamic nature of histone modifications is maintained by opposing enzyme families—"writers" that add modifications, "erasers" that remove them, and "readers" that recognize these marks and recruit effector complexes to implement functional consequences [8].

Functional Roles of Key Histone Modifications

Activation-Associated Histone Marks

Activation-associated histone marks typically create an open chromatin configuration that facilitates transcription factor binding and recruitment of the transcriptional machinery. These modifications are frequently found at promoters and enhancers of actively transcribed genes.

Table 1: Activation-Associated Histone Modifications

| Histone Mark | Chromatin State | Genomic Location | Functional Role | Reader/Effector Proteins |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 | Euchromatin | Promoters, Transcriptional Start Sites (TSS) | Promotes PIC assembly, recruits TFIID via TAF3 [8] | TFIID/TAF3, SAGA complex |

| H3K9ac | Euchromatin | Promoters, Enhancers | Neutralizes histone charge, decompacts chromatin [9] | Bromodomain-containing proteins |

| H3K14ac | Euchromatin | Promoters, Enhancers | Neutralizes histone charge, decompacts chromatin [9] | Bromodomain-containing proteins |

| H3K27ac | Euchromatin | Active Enhancers, Promoters | Distinguishes active from poised enhancers [8] | Bromodomain-containing proteins |

| H3K4me1 | Euchromatin | Enhancers | Primarily marks enhancer elements [8] | COMPASS-like complexes |

| H3K36me3 | Euchromatin | Gene Bodies | Associated with transcriptional elongation [8] | Histone deacetylase complexes |

| H3K79me3 | Euchromatin | Gene Bodies | Associated with actively transcribing genes [8] | DOT1L complex |

Repression-Associated Histone Marks

Repression-associated histone marks promote chromatin condensation and establish transcriptionally silent regions of the genome. These modifications facilitate the formation of heterochromatin and can be dynamically regulated during development.

Table 2: Repression-Associated Histone Modifications

| Histone Mark | Chromatin State | Genomic Location | Functional Role | Reader/Effector Proteins |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3K27me3 | Facultative Heterochromatin | Developmentally silenced genes | Deposited by PRC2, maintains developmental gene silencing [9] [12] | PRC1 complex (CBX proteins) |

| H3K9me3 | Constitutive Heterochromatin | Repetitive regions, telomeres | Hallmark of constitutive heterochromatin [9] [12] | HP1 proteins |

| H3K9me2 | Heterochromatin | Silent genomic regions | Contributes to heterochromatin formation [10] | HP1 proteins |

| H4K20me3 | Heterochromatin | Silent genomic regions | Associated with constitutive heterochromatin [8] | L3MBTL1 |

Specialized Chromatin States

Bivalent chromatin represents a specialized state where activation and repression marks co-exist, particularly in embryonic stem cells. These domains contain both H3K4me3 (activation) and H3K27me3 (repression) marks, which poise developmental genes for rapid activation or stable silencing upon differentiation cues [8]. This configuration allows pluripotent cells to maintain developmental plasticity while keeping lineage-specific genes transcriptionally silent until the appropriate differentiation signal is received.

Diagram 1: Histone Modification Regulatory Pathways. This diagram illustrates how specific histone modifications lead to distinct chromatin states and functional outcomes, including the specialized bivalent domain that poises genes for activation.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing (ChIP-seq) for Histone Modification Analysis

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) has emerged as the gold standard method for genome-wide mapping of histone modifications and chromatin-associated proteins [13] [11]. This powerful technique combines the specificity of immunological assays with the comprehensive nature of next-generation sequencing to precisely localize epigenetic marks across the entire genome.

Standard ChIP-seq Workflow

The fundamental ChIP-seq protocol involves several critical steps: (1) crosslinking of proteins to DNA using formaldehyde to preserve endogenous interactions; (2) chromatin fragmentation typically through sonication or micrococcal nuclease (MNase) digestion; (3) immunoprecipitation with antibodies specific to the histone modification of interest; (4) library preparation from immunoprecipitated DNA; and (5) high-throughput sequencing followed by computational analysis [13] [11]. For histone modifications, chromatin is often fragmented to mononucleosome-sized fragments using MNase, which preferentially degrades linker DNA and results in higher resolution mapping [13].

Diagram 2: Standard ChIP-seq Experimental Workflow. The diagram outlines the key steps in the ChIP-seq protocol from crosslinking to bioinformatic analysis.

Advanced ChIP-seq Methodologies

Recent technological advances have addressed key limitations of conventional ChIP-seq, particularly regarding the large cell numbers required and challenges in quantitative comparisons between samples.

MINUTE-ChIP (Multiplexed Immunoprecipitation Sequencing of Chromatin) enables highly multiplexed, quantitative ChIP-seq experiments by incorporating sample barcoding prior to immunoprecipitation [14]. This innovative approach allows profiling multiple samples against multiple epitopes in a single workflow, dramatically increasing throughput while enabling accurate quantitative comparisons. The method involves: (1) lysis and chromatin fragmentation; (2) barcoding of native or formaldehyde-fixed material; (3) pooling and splitting of barcoded chromatin into parallel immunoprecipitation reactions; and (4) preparation of sequencing libraries from input and immunoprecipitated DNA [14].

cChIP-seq (carrier ChIP-seq) addresses the challenge of limited cellular material by employing a DNA-free recombinant histone carrier to maintain working ChIP reaction scale [15]. This method eliminates the need to optimize chromatin-to-antibody ratios for small cell numbers and has been successfully applied to profile H3K4me3, H3K4me1, and H3K27me3 from as few as 10,000 cells [15]. The carrier consists of chemically modified recombinant histone H3 matching the modification being assayed, which provides epitopes for antibody binding without introducing contaminating DNA that would compromise sequencing libraries.

Spike-in Chromatin Methods incorporate chromatin from a different species (e.g., Drosophila chromatin added to human samples) as an internal control for normalization, enabling more accurate quantitative comparisons between samples with different cellular contexts or experimental conditions [16].

Critical Technical Considerations

Several technical aspects are crucial for successful ChIP-seq experiments:

- Antibody Specificity: Antibody quality remains the single most important factor, as non-specific antibodies generate unreliable data [13].

- Cell Number Requirements: Standard protocols typically require 1-10 million cells, though recent advances have reduced this to 10,000 cells or fewer [13] [15].

- Chromatin Fragmentation: Sonication is preferred for transcription factor mapping, while MNase digestion provides higher resolution for histone modifications [13].

- Appropriate Controls: Input chromatin (non-immunoprecipitated) provides the optimal control for identifying true enrichment signals [13].

- Sequencing Depth: Sufficient sequencing depth is essential for robust peak detection, with requirements varying by histone modification type [13].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Histone Modification ChIP-seq

This protocol adapts robust, cost-effective methods for histone modification ChIP-seq, suitable for various biological systems including Arabidopsis thaliana plantlets and mammalian cells [17].

Crosslinking and Chromatin Extraction

- Crosslinking: For 3g of tissue or 1-10 million cells, add 1% formaldehyde (final concentration) and incubate for 15 minutes under vacuum infiltration for tissues or at room temperature for cell cultures. Quench with 125mM glycine (final concentration) for 5 minutes [17].

- Chromatin Extraction:

- Grind crosslinked tissue to fine powder in liquid nitrogen.

- Resuspend powder in 25ml Extraction Buffer 1 (50mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate) with freshly added protease inhibitors.

- Filter through 100μm mesh and centrifuge at 1,500 × g for 15 minutes.

- Wash pellet with Extraction Buffer 2 (similar composition with adjusted detergent concentrations).

- Resuspend final pellet in 500μL Extraction Buffer 3 [17].

Chromatin Fragmentation and Immunoprecipitation

- Chromatin Fragmentation: Sonicate chromatin using a focused ultrasonicator (e.g., Covaris S220) to achieve 150-500bp fragments. Verify fragment size by agarose gel electrophoresis [17].

- Immunoprecipitation:

- Pre-clear chromatin with Protein A/G magnetic beads for 1 hour at 4°C.

- Incubate supernatant with 1-5μg of modification-specific antibody overnight at 4°C with rotation.

- Add pre-washed Protein A/G magnetic beads and incubate for 2 hours.

- Wash sequentially with: Low Salt Wash Buffer (150mM NaCl), High Salt Wash Buffer (500mM NaCl), LiCl Wash Buffer (250mM LiCl), and TE Buffer [17].

- Elution and De-crosslinking: Elute immunoprecipitated DNA with Elution Buffer (1% SDS, 100mM NaHCO3) at 65°C for 15 minutes. Reverse crosslinks by adding 200mM NaCl and incubating at 65°C overnight [17].

Library Preparation and Sequencing

- DNA Purification: Treat with RNase A and Proteinase K, then purify DNA using phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol extraction and ethanol precipitation.

- Library Construction: Use commercial library preparation kits compatible with low DNA input. Incorporate size selection steps to optimize fragment distribution.

- Quality Control and Sequencing: Quantify libraries using fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit dsDNA HS Assay). Validate quality by bioanalyzer before sequencing on appropriate Illumina platforms [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Histone Modification ChIP-seq

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Core Histone Antibodies | Anti-H3K4me3 (Millipore 07-449), Anti-H3K27me3 (Millipore 07-449), Anti-H3K9ac (Millipore 07-352), Anti-H3K14ac (Millipore 07-353) | Specific recognition of modified histone residues for immunoprecipitation [17] |

| Chromatin Extraction Reagents | Formaldehyde, Glycine, Protease Inhibitor Cocktails, Triton X-100, SDS | Crosslinking, quenching, and maintaining protein integrity during chromatin preparation [17] |

| Immunoprecipitation Materials | Protein A/G Magnetic Beads (Dynabeads), Low/High Salt Wash Buffers, LiCl Wash Buffer | Capture antibody-antigen complexes and remove non-specifically bound material [17] |

| DNA Purification & Library Prep | Phenol:Chloroform:Isoamyl Alcohol, GlycoBlue Coprecipitant, Proteinase K, RNase Cocktail, DNA Clean/Concentrator Kits | Isolation of purified DNA and preparation for next-generation sequencing [17] |

| Quality Control Tools | Qubit Fluorometer, Bioanalyzer, Agarose Gel Electrophoresis | Quantification and quality assessment of DNA throughout the protocol [17] |

Histone modifications constitute a sophisticated regulatory system that orchestrates chromatin dynamics and gene expression patterns critical for development, cellular differentiation, and disease pathogenesis. The comprehensive characterization of these epigenetic marks through ChIP-seq methodologies provides invaluable insights into their genomic distribution and functional consequences. Continued refinement of ChIP-seq protocols, particularly toward lower input requirements and enhanced quantitative capabilities, will further advance our understanding of the histone code and its implications for fundamental biology and therapeutic development. The integration of these epigenetic analyses with other genomic datasets promises to unravel the complex regulatory networks that govern cellular identity and function.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) has emerged as the preferred method for determining genome-wide binding patterns of transcription factors and other chromatin-associated proteins, as well as for mapping histone modifications [18]. This technology enables researchers to capture DNA transcription factors, histone modification sites, epigenetic alterations, and gene regulatory network signatures with high specificity and sensitivity [19]. The fundamental principle of ChIP-seq involves cross-linking proteins to DNA, shearing chromatin, immunoprecipitating the protein-DNA complexes using specific antibodies, and then sequencing the bound DNA fragments [19]. The resulting sequences are aligned to a reference genome to identify enriched regions, providing a comprehensive picture of protein-DNA interactions across the entire genome.

The clinical relevance of ChIP-seq technology is substantial, particularly in elucidating pathologic molecular mechanisms underlying cancer and other diseases [19]. Epigenetic imbalances across disease and health conditions often involve histone modification and altered transcription factors, which can be systematically profiled using ChIP-seq. For instance, heterogeneity of chromatin states can lead to treatment resistance in breast cancer, where cells tend to lose repressive histone modifications and increase expression of genes promoting resistance to cancer treatment [19]. The technology has revolutionized epigenetics research by providing higher signal-to-background noise ratios compared to previous methodologies like ChIP-on-chip, though significant challenges remain in data analysis due to variation in sample preparation and sequencing errors [18].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard ChIP-seq Protocol

The standard ChIP-seq protocol begins with formaldehyde cross-linking to fix protein-DNA interactions within the cellular context [19]. Following cross-linking, cells are lysed and chromatin is sheared into smaller fragments typically ranging from 200-600 base pairs using sonication. The sheared chromatin is then incubated with antibodies specific to the protein or histone modification of interest. The immuno-complexes formed are precipitated and purified, after which the cross-links are reversed to free the DNA fragments [19]. The purified DNA is then processed into a sequencing library, with adapters ligated for amplification and sequencing on high-throughput platforms.

Critical to successful ChIP-seq experiments is the inclusion of appropriate control samples. Input DNA (non-immunoprecipitated genomic DNA) serves as a essential control for normalizing background noise and identifying artifacts related to sequencing and mapping biases [20]. The quality of antibodies used for immunoprecipitation significantly impacts results, requiring validation for specificity and efficiency. Ideal ChIP-seq experiments should have less than three reads per position as measured by the Non-Redundant Fraction (NRF) of aligned reads, and duplicate reads introduced by PCR amplification should be removed using tools like Picard to prevent biases during peak calling [19].

Double-Crosslinking ChIP-seq (dxChIP-seq) Protocol

Recent advancements have led to the development of dxChIP-seq, a double-crosslinking chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing protocol that improves mapping of chromatin factors, including those that do not bind DNA directly, while enhancing signal-to-noise ratio [21]. This method is particularly valuable for challenging chromatin targets where conventional single cross-linking may be insufficient.

The dxChIP-seq protocol involves the following key steps:

- Double-Crosslinking: Initial cross-linking with formaldehyde is followed by a secondary cross-linking step using additional agents to stabilize more transient or indirect protein-DNA interactions.

- Focused Ultrasonication: Chromatin is sheared using optimized ultrasonication conditions to generate appropriately sized fragments while maintaining epitope integrity for immunoprecipitation.

- Immunoprecipitation: Specific antibodies are used to pull down the protein-DNA complexes of interest, with the double-crosslinking providing enhanced stability for complex retention.

- DNA Purification and Library Preparation: Cross-links are reversed, and DNA is purified before standard library preparation for sequencing.

This protocol has demonstrated particular utility for studying chromatin factors that lack direct DNA-binding activity and cannot be conventionally profiled, making it compatible with adherent cells and complex multicellular structures [21]. The double-crosslinking approach significantly improves the recovery of genuine protein-DNA interactions while reducing background noise.

PerCell Method for Quantitative Comparisons

A significant challenge in ChIP-seq analysis has been the quantitative comparison of signals across different experimental conditions or samples. The recently developed PerCell methodology addresses this by integrating cell-based chromatin spike-in with a flexible bioinformatic pipeline [16]. This strategy combines well-defined cellular spike-in ratios of orthologous species' chromatin to facilitate highly quantitative comparisons of 2D chromatin sequencing across experimental conditions.

The key steps in the PerCell method include:

- Spike-in Addition: A defined ratio of chromatin from an orthologous species (e.g., Drosophila chromatin for human samples) is added to each sample prior to immunoprecipitation.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Standard library preparation is performed, followed by sequencing.

- Bioinformatic Normalization: The pipeline separates reads aligning to the experimental genome and the spike-in genome, using the spike-in signals to normalize for technical variations between samples.

This method enables quantitative, internally normalized chromatin sequencing and has been successfully demonstrated in zebrafish embryos and human cancer cells [16]. The approach promotes uniformity of data analyses and sharing across labs, representing a significant advancement for cross-species comparative epigenomics.

Quantitative Data Analysis in ChIP-seq

Statistical Methods for Differential Binding Analysis

Quantitative comparison of multiple ChIP-seq datasets requires specialized statistical methods to detect genomic regions showing differential protein binding or histone modification. Several computational approaches have been developed to address this challenge, each with distinct methodologies and applications:

Table 1: Statistical Methods for ChIP-seq Quantitative Comparison

| Method | Key Features | Considerations for Control Data | Biological Replicates | Multiple-Factor Designs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChIPComp | Uses Poisson distribution for IP counts; models background and biological signals separately; accounts for signal-to-noise ratios [20] | Explicitly estimates background using spatial correlation of control reads [20] | Supports biological replicates through linear model framework [20] | Handles multiple-factor experimental designs [20] |

| MAnorm | Uses common peaks as reference for normalization; MA plot followed by robust linear regression [18] | Does not explicitly incorporate control data in normalization [20] | Primarily designed for two-group comparisons [20] | Limited extensibility to complex designs [20] |

| DBChIP/DiffBind | Applies RNA-seq differential expression methods to candidate regions; subtracts normalized control counts [20] | Subtracts control counts from IP counts, assuming additive background [20] | Depends on underlying DE method used [20] | Limited to simple designs [20] |

The ChIPComp method represents a comprehensive approach that takes into consideration genomic background measured by the control data, different signal-to-noise ratios in experiments, biological variances from replicates, and multiple-factor experimental designs [20]. It employs a two-step procedure where peaks are first detected from all datasets and then unioned to form a single set of candidate regions. The read counts from IP experiments at these candidate regions are assumed to follow Poisson distribution, with underlying Poisson rates modeled as an experiment-specific function of artifacts and biological signals [20].

MAnorm provides a robust model for quantitative comparison of ChIP-seq data sets, based on the empirical assumption that if a chromatin-associated protein has a substantial number of peaks shared in two conditions, the binding at these common regions will tend to be determined by similar mechanisms and thus should exhibit similar global binding intensities across samples [18]. The method plots the log2 ratio of read density between two samples (M) against the average log2 read density (A) for all peaks, then applies robust linear regression to fit the global dependence between the M-A values of common peaks [18].

Analysis of Histone Modification Interplay

ChIP-seq has been instrumental in elucidating the complex interplay between different histone modifications. A recent study investigating histone post-translational modifications (PTMs) in the phytopathogenic fungus Pyricularia oryzae utilized ChIP-seq analysis of knock-out mutants lacking enzymes responsible for H3K4me2/3, H3K9me3, or H3K27me3 [1]. This research revealed how loss of specific PTMs alters other PTMs and gene expression in a compartment-specific manner, with distinct effects across euchromatin and heterochromatin regions.

The study defined genomic compartments based on histone modification patterns:

- Euchromatin (EC): Characterized by H3K4me2-rich segments, containing 26.9% of genes

- Constitutive Heterochromatin (cHC): Marked by H3K9me3-rich segments, containing only 0.6% of genes

- Facultative Heterochromatin (fHC): Defined by H3K27me3-rich segments, containing 20.2% of genes

Notably, the researchers identified two distinct subcompartments of facultative heterochromatin: K4-fHC (adjacent to euchromatin) and K9-fHC (adjacent to constitutive heterochromatin) [1]. Both contain poorly conserved genes, but K9-fHC harbors more transposable elements, while K4-fHC is more enriched for genes upregulated during infection, including effector-like genes. This compartment-specific analysis demonstrates how ChIP-seq can reveal nuanced relationships between histone modifications and genomic function.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful ChIP-seq experiments require careful selection of reagents and materials to ensure high-quality results. The following table outlines key components essential for histone modification analysis using ChIP-seq:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for ChIP-seq

| Reagent/Material | Function | Considerations for Histone Modification Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Specific Antibodies | Immunoprecipitation of protein-DNA complexes | Critical for specificity; require validation for each histone modification (e.g., H3K4me3, H3K27me3) [1] |

| Formaldehyde | Cross-linking protein to DNA | Standard concentration is 1%; double-crosslinking protocols use additional agents [21] |

| Protein A/G Magnetic Beads | Capture of antibody-protein-DNA complexes | More efficient than agarose beads for low-abundance targets |

| Chromatin Shearing Reagents | Fragment chromatin to appropriate size | Sonication equipment and conditions must be optimized for each cell type |

| DNA Purification Kits | Cleanup of immunoprecipitated DNA | Spin-column based systems provide efficient recovery of small DNA fragments |

| Library Preparation Kits | Prepare sequencing libraries from ChIP DNA | Should be compatible with low-input DNA amounts typical of ChIP experiments |

| Spike-in Chromatin | Normalization between samples | Orthologous species chromatin (e.g., Drosophila for human samples) for quantitative comparisons [16] |

| PCR Amplification Reagents | Amplify library fragments for sequencing | Must minimize amplification bias; incorporate unique molecular identifiers |

The quality of antibodies is particularly crucial for histone modification studies, as different modifications require highly specific antibodies for accurate immunoprecipitation [1]. Additionally, the development of spike-in chromatin reagents has significantly improved the ability to make quantitative comparisons between samples and experimental conditions [16].

Data Visualization and Interpretation

Visualization Techniques for ChIP-seq Data

Data visualization is a critical component of ChIP-seq analysis, enabling researchers to interpret enrichment patterns and validate results. The visualization process typically begins with the creation of bigWig files from alignment files (BAM format) [22]. bigWig is an indexed binary format useful for dense, continuous data that can be displayed in genome browsers as graphs/tracks. Tools like deepTools provide utilities such as bamCoverage and bamCompare for converting BAM files to bigWig format, with options for normalization using methods like BPM (Bins Per Million), which is similar to TPM in RNA-seq [22].

Two powerful visualization approaches for ChIP-seq data are profile plots and heatmaps, which can be generated using deepTools [22]. Profile plots show the average read density across all regions of interest, such as transcription start sites (TSS), providing a global evaluation of enrichment patterns. Heatmaps display individual regions as rows, sorted by signal intensity, allowing researchers to identify patterns and subgroups within the data. These visualizations are particularly useful for comparing histone modification patterns across multiple samples or conditions, such as different experimental treatments or genetic backgrounds.

Workflow Diagram for ChIP-seq Data Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the complete ChIP-seq data analysis workflow, from raw data processing to biological interpretation:

ChIP-seq Data Analysis Workflow

Experimental Protocol Diagram

The experimental workflow for ChIP-seq, including the double-crosslinking variant, can be summarized as follows:

ChIP-seq Experimental Protocol Workflow

ChIP-seq technology continues to evolve as a powerful tool for genome-wide epigenetic profiling, with recent methodological advancements enhancing its quantitative capabilities and application scope. The development of more sophisticated protocols like dxChIP-seq and analytical frameworks such as ChIPComp and PerCell has addressed significant challenges in quantitative comparison across samples and experimental conditions [20] [21] [16]. These advancements are particularly relevant for drug development professionals seeking to understand epigenetic mechanisms of disease and identify potential therapeutic targets.

The integration of ChIP-seq with other genomic approaches, such as RNA-seq, provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the functional consequences of epigenetic modifications on gene regulation [1]. As the technology continues to mature with improvements in antibody specificity, sequencing efficiency, and computational methods, ChIP-seq remains an indispensable tool for unraveling the complex landscape of epigenetic regulation in health and disease. The rigorous statistical methods and standardized protocols outlined in this application note provide researchers with a solid foundation for implementing robust ChIP-seq studies focused on histone modification analysis.

Linking Histone Modifications to Gene Regulation, Development, and Disease

Histone modifications are post-translational alterations to histone proteins—such as methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination—that play a pivotal role in regulating gene expression without changing the underlying DNA sequence [11] [23]. These epigenetic modifications influence chromatin structure by either relaxing it to activate gene expression or compacting it to repress transcription, thereby controlling critical cellular processes in development, health, and disease [11] [23]. Disruptions in these modifications are implicated in various human diseases, including cancer, immunodeficiency disorders, and neurological conditions like epilepsy [11] [24].

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) has become the gold-standard technique for investigating these protein-DNA interactions on a genome-wide scale [11] [23] [5]. This powerful method combines the specificity of chromatin immunoprecipitation with the high-throughput capabilities of next-generation sequencing, enabling researchers to precisely map histone modification patterns across the entire genome and compare these epigenetic landscapes between different biological states [11].

Biological Foundations of Histone Modifications

Major Types of Histone Modifications and Their Functions

Histone modifications primarily occur on the N-terminal tails of histones that extend from the nucleosome surface, and they function through at least two key mechanisms: altering the histone's electrostatic charge to change chromatin structure, or creating binding sites for specific protein recognition modules [11]. These modifications can be broadly categorized as either activating marks that promote gene expression or repressive marks that facilitate gene silencing [23].

Table 1: Key Histone Modifications and Their Biological Functions

| Modification | Associated Function | Chromatin State | Gene Expression Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 | Promoter-associated | Euchromatin | Activation |

| H3K27ac | Enhancer-associated | Euchromatin | Activation |

| H3K27me3 | Polycomb repression | Facultative Heterochromatin | Repression |

| H3K9me3 | Constitutive heterochromatin | Heterochromatin | Repression |

| H3K36me3 | Elongation-associated | Euchromatin | Activation |

These modifications contribute to essential processes including the silencing of transposable elements and the regulation of specific genes during development, with their misplacement potentially leading to unhealthy cell phenotypes observed in aging, cancer, and in response to challenging environmental conditions [11].

Crosstalk Between Epigenetic Modifications

Histone modifications do not function in isolation but engage in complex crosstalk mechanisms with other epigenetic regulators, including DNA methylation, RNA methylation, and non-coding RNAs [25] [24]. This interplay creates a sophisticated regulatory network that fine-tunes gene expression programs. For instance, in epilepsy research, studies have demonstrated coordinated interactions between DNA methylation changes, histone modifications, and non-coding RNAs that collectively contribute to disease pathogenesis [24]. Understanding these interactions is crucial for deciphering the epigenetic code and its role in both normal development and disease progression.

ChIP-seq Protocol for Histone Modification Analysis

Experimental Workflow and Best Practices

The ChIP-seq procedure involves multiple critical steps that must be carefully optimized to ensure high-quality, reproducible results. The ENCODE and modENCODE consortia have established comprehensive guidelines based on their experience with thousands of ChIP-seq experiments [5].

Table 2: ChIP-seq Experimental Steps and Key Considerations

| Step | Procedure | Key Parameters | Quality Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-linking | Formaldehyde treatment | Concentration & duration | Preserved protein-DNA interactions |

| Chromatin Shearing | Sonication or enzymatic digestion | Fragment size (100-300 bp) | Appropriate size distribution |

| Immunoprecipitation | Antibody incubation | Antibody specificity & concentration | High signal-to-noise ratio |

| DNA Purification | Cross-link reversal & cleanup | Yield and purity | Sufficient material for library prep |

| Library Preparation & Sequencing | Adapter ligation & NGS | Sequencing depth | 20-40 million reads for histone marks |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete ChIP-seq procedure from sample preparation to data acquisition:

Antibody Validation and Quality Control

Antibody specificity is arguably the most critical factor in successful ChIP-seq experiments. According to ENCODE guidelines, antibodies must undergo rigorous validation using both primary and secondary characterization methods [5]. For antibodies targeting transcription factors, immunoblot analysis should show that the primary reactive band contains at least 50% of the signal observed on the blot, ideally corresponding to the expected size of the target protein [5]. Alternative validation methods include immunofluorescence to confirm proper subcellular localization, or demonstration that the signal is reduced by siRNA knockdown or mutation of the target gene [5].

For histone modification-specific antibodies, the ENCODE consortium recommends using peptide-based competition assays as the primary characterization method, where the immunoprecipitation signal should be significantly reduced by pre-incubation with the target peptide but not with a non-specific control peptide [5]. These quality control measures are essential for generating reliable and interpretable ChIP-seq data.

Computational Analysis of ChIP-seq Data

Data Processing and Peak Calling

The analysis of ChIP-seq data involves multiple computational steps to transform raw sequencing reads into biologically meaningful information. A typical bioinformatics pipeline includes quality control, read alignment, peak calling, and annotation [26] [23].

A practical ChIP-seq analysis workflow can be implemented using platforms like Galaxy, which provides accessible tools for researchers without extensive programming expertise [26]. The key steps include:

- Quality Control: Using Fastp for read quality assessment and adapter trimming

- Read Alignment: Bowtie2 for mapping reads to a reference genome

- Duplicate Marking: MarkDuplicates to identify PCR artifacts

- Peak Calling: MACS2 for identifying significantly enriched regions

- Peak Annotation: ChIPseeker for associating peaks with genomic features

- Visualization: bamCoverage and computeMatrix for generating coverage tracks and heatmaps [26]

For histone modifications, which often exhibit broad genomic domains rather than sharp peaks, specialized peak-calling algorithms such as HOMER or SICER may be more appropriate than standard tools like MACS2 [23] [5].

Advanced Analysis Techniques

Beyond basic peak calling, advanced analytical approaches enable deeper biological insights. Differential peak analysis compares histone modification patterns between experimental conditions (e.g., disease vs. healthy samples) to identify epigenetic changes associated with specific phenotypes [11] [23]. Integrative analyses combine ChIP-seq data with other genomic datasets, such as RNA-seq or ATAC-seq, to link histone modifications with changes in gene expression or chromatin accessibility [23].

Mathematical modeling of ChIP-seq data often employs probabilistic distributions such as the Poisson or negative binomial distributions to account for the count-based nature of sequencing data [23]. The probability of observing k reads in a given genomic region can be modeled using the Poisson distribution:

[P(k | \lambda) = \frac{\lambda^k e^{-\lambda}}{k!}]

where (\lambda) represents the expected number of reads in the region under the null hypothesis of no enrichment [23].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Histone Modification ChIP-seq

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Quality Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Histone Modification Antibodies | H3K4me3, H3K27ac, H3K27me3, H3K9me3 | Target-specific immunoprecipitation | Specificity validated by immunoblot or peptide competition |

| Cell Fixation Reagents | Formaldehyde | Cross-links proteins to DNA | Freshly prepared, optimal concentration |

| Chromatin Shearing Reagents | Sonication reagents, MNase enzyme | Fragment chromatin to optimal size | Fragment size distribution (100-300 bp) |

| Immunoprecipitation Beads | Protein A/G magnetic beads | Antibody binding and complex isolation | Binding capacity, non-specific background |

| Library Preparation Kits | Illumina, NEB Next Ultra II | Prepare sequencing libraries | Efficiency, bias, compatibility with low input |

| Quality Control Assays | Qubit, Bioanalyzer, qPCR | Quantify and qualify DNA | Sensitivity, accuracy, reproducibility |

Applications in Disease Research and Therapeutics

Histone Modifications in Human Diseases

Abnormal histone modification patterns are increasingly recognized as contributing factors in various human diseases. In cancer, global changes in histone methylation and acetylation landscapes can lead to the silencing of tumor suppressor genes or activation of oncogenes [11] [24]. Neurological disorders such as epilepsy also demonstrate altered histone modification profiles, with studies revealing distinct histone acetylation and methylation patterns in patient-derived samples and animal models of the disease [24].

A particularly intriguing application emerges from research on paternal epigenetic inheritance, where father's environmental exposures (e.g., to pollutants, diet, or stress) can induce histone modifications in sperm that influence offspring health and disease susceptibility [27]. This demonstrates how histone modifications can serve as molecular memories of environmental exposures that transcend generations.

Therapeutic Targeting of Histone Modifications

The reversible nature of histone modifications makes them attractive targets for therapeutic intervention. Epigenetic drugs that target histone-modifying enzymes, such as histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors and histone methyltransferase inhibitors, have shown promise in preclinical models and clinical trials for various cancers and neurological disorders [24]. For instance, the ketogenic diet, an established therapy for drug-resistant epilepsy, may exert its effects partly through modifying histone acetylation and methylation patterns, thereby influencing the expression of genes involved in neuronal excitability and seizure threshold [24].

The following diagram illustrates how histone modifications contribute to disease mechanisms and potential intervention points:

Future Directions and Concluding Remarks

The field of histone modification research continues to evolve rapidly with emerging technologies that promise to deepen our understanding of epigenetic regulation. Single-cell ChIP-seq methods now enable the analysis of chromatin states at single-cell resolution, revealing heterogeneity in histone modification patterns within cell populations that was previously masked in bulk analyses [23]. Advances in low-input ChIP-seq protocols facilitate the study of rare cell populations and clinical samples where material is limited, opening new avenues for translational epigenomics research [23].

Future directions include the integration of ChIP-seq with other multi-omics approaches, the development of more sensitive and specific epigenetic editing tools, and the application of sophisticated computational methods to decipher the complex language of histone modifications [25] [23]. The ongoing development of standardized guidelines and quality metrics by consortia such as ENCODE ensures that ChIP-seq data will continue to be a reliable resource for exploring the epigenetic basis of development, health, and disease [5].

As research in this field advances, the comprehensive mapping of histone modifications across different cell types, developmental stages, and disease conditions will undoubtedly yield novel biomarkers for diagnosis and prognosis, as well as new targets for epigenetic therapy across a wide spectrum of human diseases.

Executing a Robust ChIP-seq Protocol: A Step-by-Step Guide

Within the framework of a thesis investigating ChIP-seq protocols for histone modification analysis, rigorous experimental design is paramount for generating biologically meaningful and statistically robust data. The Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) project has established comprehensive guidelines that serve as a gold standard for the field, providing detailed recommendations on key aspects such as control experiments, biological replication, and sequencing depth [5]. Adherence to these guidelines ensures that the resulting data can accurately distinguish specific biological signals from technical artifacts and background noise, a consideration that is particularly critical for the broad enrichment patterns characteristic of many histone modifications. This protocol outlines the application of these principles, focusing on the specific requirements for histone mark profiling to support high-quality research in drug development and basic science.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table catalogues the essential materials required for a successful ChIP-seq experiment, particularly for histone modification studies.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ChIP-seq

| Item | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| Specific Antibody | The core reagent for immunoprecipitation (IP). It must be highly specific to the target histone modification. ENCODE guidelines require rigorous validation [5]. |

| Control Chromatin (Input) | A no-IP control sample (sonicated cross-linked chromatin) that is crucial for background modeling and peak calling. It must be sequenced to at least the same depth as the IP samples [28]. |

| Barcoded Adapters (for Multiplexing) | Short, unique DNA sequences that allow multiple samples to be pooled and sequenced simultaneously in a single lane, reducing batch effects and costs [14]. |

| Spike-in Chromatin | A reference chromatin (e.g., from D. melanogaster) added to the sample before IP. It enables normalization for technical variation and quantitative comparisons between samples [14]. |

| Cell Line/Tissue with Validated Epitope | The biological material expressing the histone modification of interest. The cell type and condition should be relevant to the research question. |

| Library Preparation Kit | A commercial kit containing the necessary enzymes and buffers to convert immunoprecipitated DNA into a sequencing-ready library. |

ENCODE Guidelines for Experimental Design

Antibody Validation and Specificity

The quality of a ChIP-seq experiment is fundamentally dependent on the specificity of the antibody used for the immunoprecipitation [5].

- Primary Characterization: For antibodies against histone modifications, the primary characterization is typically performed using peptide-based immunoassays, such as peptide dot blots or ELISAs. The antibody should show strong reactivity with the target modification and minimal cross-reactivity with other similar histone peptides [5].

- Secondary Characterization: A successful ChIP-seq experiment itself, demonstrating the expected genomic profile (e.g., enrichment at known active promoters for H3K4me3), serves as a critical secondary validation [5].

Biological Replicates and Controls

Sound experimental design must account for and partition biological variation from technical variation [28].

- Biological Replicates: Biological replicates (samples derived from different biological sources) are essential. While two replicates may suffice for descriptive binding characterization, a minimum of three is required for any statistical analysis of occupancy patterns between different conditions [28]. If small differences in occupancy are expected, increasing the number of replicates provides more statistical power than simply sequencing deeper [28].

- Input Controls: The use of control experiments is crucial for the analysis of ChIP-seq data. Input chromatin (genomic DNA that has been cross-linked and fragmented but not subjected to immunoprecipitation) is the most widely used control [28]. It is required to model the local background signal and to reliably detect binding events. Each biological replicate of a ChIP sample should have its own matching input control, which must be sequenced separately—pooling of inputs is not recommended [28].

Sequencing Depth and Read Configuration

The required sequencing depth is a direct function of the signal structure of the histone mark being studied [28].

- Sequencing Depth: Recommendations for sequencing depth vary based on the nature of the histone mark, with broad marks requiring significantly greater depth than point-source factors. It is vital that samples are sequenced to a depth sufficient to detect binding events in each replicate independently; if replicates must be pooled to call peaks, the sequencing was too shallow [28].

- Single-End vs. Paired-End Reads: For point-source marks like H3K4me3, single-end (SE) sequencing is often sufficient. However, for broader enrichment domains (e.g., H3K27me3, H3K36me3), paired-end (PE) sequencing is recommended, as it improves mapping confidence and directly measures fragment size, which otherwise must be modeled and is often inaccurate for this type of data [28].

Table 2: ENCODE Recommended Sequencing Depth for ChIP-seq

| Signal Type | Example Targets | Recommended Depth (Uniquely Mapped Reads) | Read Configuration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Point Source | Transcription Factors, H3K4me3 | 20 - 25 Million [28] | SE is usually sufficient [28] |

| Mixed Signal | H3K36me3 | ~35 Million [28] | PE is recommended [28] |

| Broad Signal | H3K27me3, H3K9me3 | 40 - >55 Million [28] | PE is recommended [28] |

Experimental Protocol: MINUTE-ChIP for Quantitative Histone Modification Profiling

This detailed protocol is adapted from the MINUTE-ChIP (Multiplexed Quantitative Chromatin Immunoprecipitation-Sequencing) method, which enables highly multiplexed, quantitative comparisons of histone modifications [14]. The entire workflow can be completed within one week.

Sample Preparation and Barcoding

Day 1: Cell Lysis, Chromatin Fragmentation, and Barcoding

- Cell Lysis and Cross-linking: Harvest the cell line or tissue of interest. For histone modifications, the protocol can be performed on native chromatin, but formaldehyde fixation (e.g., 1% for 10 minutes at room temperature) is common. Quench the cross-linking reaction with glycine.

- Chromatin Preparation: Lyse cells and isolate nuclei. Fragment the chromatin to a target size of 100–300 bp using sonication or enzymatic digestion (e.g., with MNase).

- Chromatin Quantification: Quantify the fragmented chromatin using a fluorescence-based assay.

- Barcoding/Labeling: For each sample, use a unique barcoded adapter to label the chromatin by ligation. This step tags the DNA from each sample with a unique DNA sequence, allowing multiple samples to be pooled later.

Pooling, Immunoprecipitation, and Library Preparation

Day 2: Multiplexed Immunoprecipitation

- Pooling: Combine equal amounts of each barcoded chromatin sample into a single tube. This creates a multiplexed chromatin pool.

- Immunoprecipitation: Split the multiplexed pool into multiple aliquots for parallel immunoprecipitation. To each aliquot, add the specific antibody for a distinct histone modification (e.g., one tube for H3K4me3, another for H3K27me3). Include a portion of the pooled chromatin as the "multiplexed input" control. Perform the IP overnight at 4°C with rotation.

- Washing and Elution: The next day, collect the antibody-chromatin complexes using protein A/G beads. Wash the beads stringently to remove non-specifically bound chromatin. Elute the immunoprecipitated DNA from the beads and reverse the cross-links.

Day 3-4: Library Preparation and Sequencing

- Library Construction: Prepare next-generation sequencing libraries from both the immunoprecipitated DNA and the saved multiplexed input control DNA. This involves end-repair, A-tailing, and adapter ligation.

- Library Amplification and Quantification: Amplify the libraries by PCR and purify them. Quantify the final libraries using a high-sensitivity assay.

- Sequencing: Pool the finished libraries and sequence on an appropriate Illumina platform to a depth that meets or exceeds the recommendations in Table 2 for your target histone marks.

Data Analysis Pipeline

Day 5: Bioinformatic Analysis

The MINUTE-ChIP protocol includes a dedicated analysis pipeline [14]. The key steps are summarized in the workflow below and generally include:

- Demultiplexing: Assign sequenced reads to their original sample based on the barcodes.

- Alignment: Map the demultiplexed reads to the reference genome.

- Quantitative Scaling: The pipeline autonomously generates quantitatively scaled ChIP-seq tracks using the multiplexed input control and/or spike-in chromatin for normalization, enabling direct comparison between samples and conditions [14].

- Peak Calling and QC: Identify enriched regions (peaks) for each histone mark and generate quality control metrics.

Statistical Considerations for Quantitative Comparison

Quantitative comparison of multiple ChIP-seq datasets to detect differential histone modification regions presents statistical challenges beyond simple peak overlapping [20]. Overlapping analysis, which relies on comparing binary peak calls, is highly dependent on arbitrary thresholds and ignores quantitative differences [20]. Robust statistical methods are required to account for genomic background, different signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs) between experiments, and biological variation [20]. The ChIPComp method, for instance, uses a generalized linear model framework within a linear model to test for differential binding, while properly incorporating control data and SNR from different experiments [20]. The MINUTE-ChIP protocol includes a dedicated pipeline that automatically performs this kind of quantitative normalization and comparison [14].

Within the framework of a broader thesis on Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) for histone modification analysis, the initial steps of chromatin preparation are paramount. The integrity of the entire dataset hinges on the precise execution of crosslinking, sonication, and rigorous quality control. These foundational procedures ensure the accurate capture of in vivo protein-DNA interactions and generate high-quality sequencing libraries. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, focusing on the critical pre-analytical phase of ChIP-seq. The guidelines herein are synthesized from established consortium standards and current best practices to ensure the generation of reliable and reproducible genome-wide epigenetic data [29] [6] [30].

Core Principles of Chromatin Preparation

The goal of chromatin preparation for ChIP-seq is to stabilize and isolate protein-DNA complexes, then fragment the chromatin to a size suitable for immunoprecipitation and sequencing. For histone modifications, which are inherently stable due to the nucleosomal structure, the preparation can often be gentler than for transient transcription factors. The choice between crosslinking methods and the optimization of fragmentation are directly influenced by the nature of the histone mark being studied [29] [31]. The following workflow delineates the key stages in sample preparation leading to quality sequencing libraries.

Figure 1. Workflow for ChIP-seq Sample Preparation. The process begins with cell harvesting and cross-linking, followed by nuclei isolation and chromatin fragmentation. Critical quality control checkpoints ensure material is suitable for immunoprecipitation and sequencing.

Crosslinking Protocols

Standard Formaldehyde Crosslinking

Formaldehyde crosslinking is the most common method for stabilizing protein-DNA interactions. It creates reversible methylol adducts and Schiff base intermediates that crosslink proteins to DNA and other proteins over short distances (∼2 Å) [21].

Detailed Protocol for Adherent Cells (e.g., HeLa):

- Cell Culture and Harvesting: Grow cells to ~90% confluence in a 15 cm culture dish. For histone modifications, one chromatin preparation typically requires 1 x 10^7 to 2 x 10^7 cells [32] [31].

- Crosslinking: Add 540 µL of 37% formaldehyde or 1.25 mL of 16% methanol-free formaldehyde directly to 20 mL of culture medium to achieve a final concentration of 1%. Swirl briefly to mix and incubate for 10 minutes at room temperature [32] [31].

- Critical Note: The fixation time is a key variable. For most histone modifications, 10 minutes is sufficient. Over-fixation can reduce sonication efficiency and antigen accessibility [32].

- Quenching: Add 2 mL of 10X glycine to the dish (final concentration ~125 mM) to quench the formaldehyde. Swirl and incubate for 5 minutes at room temperature [32] [31].

- Cell Washing and Lysis:

- Remove the medium and wash the cells twice with 20 mL of ice-cold PBS.

- Scrape the cells into 2 mL of ice-cold PBS containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (PIC).

- Pellet cells by centrifugation at 1,000 x g for 5 minutes at 4°C. The cell pellet can be used immediately or frozen on dry ice and stored at -80°C [32].

- Nuclei Isolation (Optional but Recommended): Resuspend the cell pellet in 1 mL of Ice-cold ChIP Sonication Cell Lysis Buffer with PIC. Incubate on ice for 10 minutes. Pellet the cells again at 5,000 x g for 5 minutes at 4°C. Remove the supernatant and resuspend the pellet in 1 mL of ChIP Sonication Nuclear Lysis Buffer with PIC. Incubate on ice for 10 minutes before proceeding to sonication [32]. Preparing nuclei prior to sonication helps reduce background from cytoplasmic components [29].

Advanced Double-Crosslinking (dxChIP-seq)

For challenging chromatin targets or factors that do not bind DNA directly, a double-crosslinking strategy can improve mapping and enhance the signal-to-noise ratio [21].

Detailed Protocol (dxChIP-seq):

- First Crosslinking: Use a protein-protein crosslinker such as Disuccinimidyl glutarate (DSG). Resuspend the cell pellet in PBS containing DSG (often at a concentration of 2 mM) and incubate for 45 minutes at room temperature.

- Wash: Pellet the cells and wash once with cold PBS to remove excess DSG.

- Second Crosslinking: Proceed with standard formaldehyde crosslinking as described in Section 3.1, Steps 2-4.

- Note: This protocol is particularly compatible with adherent cells and complex multicellular structures, and it stabilizes larger protein complexes [21].

Table 1: Crosslinking Conditions for Different Targets