A Complete Workflow for Cell-Free DNA Methylation Biomarker Discovery: From Liquid Biopsy to Clinical Application

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the end-to-end workflow for discovering and validating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) methylation biomarkers.

A Complete Workflow for Cell-Free DNA Methylation Biomarker Discovery: From Liquid Biopsy to Clinical Application

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the end-to-end workflow for discovering and validating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) methylation biomarkers. It covers the foundational biology of cfDNA and DNA methylation, explores established and emerging methodological approaches for methylation detection, addresses key computational and analytical challenges, and outlines robust validation frameworks. By integrating the latest research and technological advancements, this resource aims to bridge the translational gap between basic discovery and the development of clinically viable, methylation-based liquid biopsy tests for cancer diagnostics and monitoring.

Laying the Groundwork: Understanding cfDNA Biology and Methylation's Role in Cancer

Cell-free DNA (cfDNA) refers to short, double-stranded DNA fragments present in virtually all bodily fluids, including plasma, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid [1]. The study of cfDNA has gained significant importance in clinical diagnostics, serving as a valuable biomarker for various conditions, including cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and prenatal testing [2] [1]. Understanding the biological origins and release mechanisms of cfDNA is fundamental to interpreting its analytical signal in research and clinical settings. The release of cfDNA is governed by three primary mechanisms: apoptosis, necrosis, and active secretion [1]. Each mechanism produces cfDNA with distinct molecular characteristics, particularly in terms of fragment size and profile, which can be leveraged for diagnostic purposes. This article details the origin and nature of cfDNA, providing a structured overview for scientists engaged in cfDNA methylation biomarker discovery.

Core Mechanisms of cfDNA Release

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of the three main cfDNA release mechanisms.

Table 1: Core Mechanisms of Cell-Free DNA Release

| Release Mechanism | Primary Fragment Sizes | Key Catalysts/Mediators | Biological Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apoptosis | 160–180 bp; nucleosomal ladder pattern [1] | Caspases, Caspase-Activated DNase (CAD) [1] | Programmed cell death; physiological and pathological processes [1] |

| Necrosis | ~10,000 bp; large, heterogeneous fragments [1] | Severe external cellular damage [1] | Trauma, injury, sepsis; unregulated cell death [1] |

| Active Secretion | 1,000–3,000 bp; associated with EVs [2] | Metabolically active processes; Extracellular Vesicles (EVs) [2] [1] | Cell-to-cell communication; living cells [1] |

The relationships between cellular processes, release mechanisms, and the resulting cfDNA characteristics are illustrated in the workflow below.

Apoptosis

Apoptosis, or programmed cell death, is widely recognized as a major source of cfDNA release from both healthy and diseased tissues [1]. This process, which can be triggered by various physiological and pathological stimuli, involves the activation of caspases. Caspases subsequently activate a specific endonuclease, Caspase-Activated DNase (CAD), which systematically cleaves chromosomal DNA at internucleosomal regions, leading to the production of mono-nucleosomal fragments [1]. The regular cleavage of DNA during apoptosis results in cfDNA that exhibits a characteristic ladder-like pattern at approximately 160–180 base pairs when visualized via gel electrophoresis [1]. A 2024 cfCRISPR (cell-free CRISPR-Cas9) screen genetically validated that genes involved in apoptotic processes are primary effectors of cfDNA release, with apoptotic regulatory genes like FADD and BCL2L1 identified as key mediators [3].

Necrosis

Necrosis is an accidental and unregulated form of cell death caused by severe external damage, such as that seen in trauma, injury, or sepsis [1]. During necrosis, cells swell and their plasma membranes disintegrate, leading to the uncontrolled release of intracellular contents, including DNA [1]. Unlike the controlled cleavage in apoptosis, chromatin is digested non-specifically during necrosis, resulting in large, heterogeneous DNA fragments often around 10,000 base pairs in length [1]. The clearance of necrotic cells is slower than that of apoptotic cells, allowing these larger DNA fragments to persist longer in the circulation and potentially promote inflammation in surrounding tissues [1].

Active Secretion

Active secretion is a regulated process whereby living cells release cfDNA through metabolically active mechanisms, independent of cell death [2] [1]. Evidence from in vitro studies indicates that this release can be associated with the percentage of cells in the G1 phase of the cell cycle and is not correlated with the level of apoptosis or necrosis [1]. A primary vehicle for the active secretion of cfDNA is extracellular vesicles (EVs), such as exosomes and microvesicles [2] [1]. These spherical phospholipid-bilayered vesicles protect their DNA cargo from degradation in the bloodstream. cfDNA associated with active secretion typically consists of longer fragments, ranging from 1,000 to 3,000 base pairs [2]. This pathway is believed to play a role in cell-to-cell communication and signaling [1].

Quantitative Insights from Key Experiments

Recent research has provided quantitative data on the contributions of different cell types and biological processes to the cfDNA pool. The table below consolidates key findings.

Table 2: Quantitative Insights from cfDNA Release Studies

| Experimental Model | Key Finding | Quantitative Result / Fragment Profile | Research Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSC-Enriched Culture (SW480 Colon Cancer Line) [2] | Cultures with CSCs release greater amounts of cfDNA. | Distinct fragment profile compared to non-enriched cultures. | Suggests CSCs are a significant source of cfDNA, influencing tumor-derived signal in liquid biopsies. |

| 24-Cell Line Panel Profiling [3] | Two distinct cfDNA release phenotypes identified. | "Left-skewed": major peak at ~167 bp.\n"Right-skewed": major peak at >1000 bp. | Confirms intrinsic cellular diversity in cfDNA release, relevant for model selection. |

| cfCRISPR Genetic Screen (MCF-10A & MCF-7) [3] | Apoptosis is a primary genetic mediator of cfDNA release. | Genes mediating release primarily involved in apoptosis (e.g., FADD, BCL2L1). | Provides genetic validation for apoptosis; suggests modulation as a method to influence cfDNA yield. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Analyzing cfDNA Release in Cell Cultures

This protocol details the methodology for assessing the quantity and fragmentation profile of cfDNA released from cell lines in vitro, as derived from recent studies [2] [3].

Materials and Equipment

- Cell Lines: Any relevant cell line of interest (e.g., SW480, MCF-10A).

- Culture Reagents: Standard culture medium (e.g., DMEM-F12), Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), Penicillin-Streptomycin, Trypsin-EDTA, sterile Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS).

- Consumables: 75 cm² cell culture flasks, 6-well plates, 50 mL conical centrifuge tubes, 0.45 µm pore-size filters.

- cfDNA Isolation & Analysis: Commercial cfDNA extraction kit, Ultrafiltration system (10 kDa membrane), Agilent Bioanalyzer or TapeStation system.

Procedure

Cell Culture and Conditioning:

- Cultivate cell lines in 75 cm² flasks under standard conditions (e.g., 37°C, 5% CO₂) until they reach 70–80% confluence.

- Discard the spent medium and wash the cell monolayer twice with sterile PBS to remove residual serum and cellular debris.

- Add a conditioned medium (e.g., standard growth medium containing 2% FBS) and incubate the cells for 48 hours [2].

Supernatant Collection and Clarification:

- Transfer the conditioned medium to 50 mL conical tubes.

- Centrifuge at 400 x g for 20 minutes at 4°C to pellet any detached cells or large debris.

- Carefully collect the supernatant and pass it through a 0.45 µm filter to ensure the complete removal of any remaining cells or particles.

- To verify the absence of cellular contamination, seed an aliquot of the filtered supernatant into a culture flask and incubate for one week, monitoring for cellular growth [2].

Concentration and cfDNA Extraction:

- Concentrate the clarified supernatant (e.g., 120 mL down to 12 mL) using an ultrafiltration system with a 10 kDa molecular weight cut-off membrane to increase the yield of cfDNA [2].

- Extract cfDNA from the concentrated supernatant using a dedicated commercial cfDNA extraction kit, following the manufacturer's instructions.

Quantification and Fragment Analysis:

- Quantify the extracted cfDNA using a fluorescence-based method suitable for low DNA concentrations.

- Analyze the fragmentation profile using a high-sensitivity automated electrophoresis system (e.g., Agilent Bioanalyzer). This will reveal the distribution of fragment sizes, allowing classification into apoptotic (~167 bp peak), necrotic (~10,000 bp), or vesicular (1,000–3,000 bp) profiles [2] [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below lists key reagents and their functions for studying cfDNA release mechanisms.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for cfDNA Release Studies

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in cfDNA Research | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Adhesive Culture System [2] | Enriches for cancer stem cell (CSC) populations. | Studying the contribution of CSCs to total cfDNA release and its transforming capacity [2]. |

| TRAIL (TNF-Related Apoptosis-Inducing Ligand) [3] | Inducer of the extrinsic apoptosis pathway. | Modulating apoptosis to investigate its direct effect on cfDNA quantity and fragment size [3]. |

| Ultrafiltration Systems (10 kDa) [2] | Concentrates cfDNA from large volumes of cell culture supernatant. | Enhancing the yield of cfDNA prior to extraction for downstream analysis [2]. |

| High-Sensitivity Electrophoresis [2] [3] | Precisely characterizes cfDNA fragment size distribution. | Differentiating between apoptotic, necrotic, and actively secreted cfDNA based on fragment length profiles. |

| cfCRISPR Screening [3] | Genome-wide genetic screen to identify mediators of cfDNA release. | Unbiased discovery of genes (e.g., FADD, BCL2L1) that regulate cfDNA release. |

DNA methylation is a fundamental epigenetic mechanism that involves the addition of a methyl group to a DNA molecule, typically at the 5-carbon position of a cytosine residue preceding a guanine, known as a CpG site, to form 5-methylcytosine (5mC) [4]. This modification does not alter the underlying DNA sequence but plays a crucial role in regulating gene expression and maintaining chromosomal stability [5]. As a key component of the epigenome, DNA methylation patterns are essential for normal development, genomic imprinting, X-chromosome inactivation, and suppression of transposable elements [6] [7]. In clinical and research settings, the analysis of cell-free DNA (cfDNA) methylation from liquid biopsies has emerged as a promising tool for non-invasive disease diagnostics, particularly in oncology [6] [8].

The Core Mechanism of DNA Methylation

DNA methylation is catalyzed by enzymes called DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), which use S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) as a methyl donor [7]. The establishment and maintenance of methylation patterns are primarily performed by DNMT3A, DNMT3B (de novo methyltransferases), and DNMT1 (maintenance methyltransferase), which faithfully copy methylation patterns during cell division [5] [9].

The functional consequence of DNA methylation depends largely on its genomic location:

- Promoter Region Methylation: Methylation of CpG islands in promoter regions is generally associated with gene silencing by preventing transcription factors from binding and recruiting proteins that promote the formation of transcriptionally inactive heterochromatin [4] [5].

- Gene Body Methylation: Methylation within the transcribed region of genes is often associated with active transcription [7].

- Enhancer Methylation: Tissue-specific methylation patterns at enhancer elements contribute to unique gene expression profiles across different cell types [4].

The following diagram illustrates how DNA methylation regulates gene expression:

DNA Methylation Patterns in Health and Disease

DNA methylation patterns are dynamically regulated throughout development and can be influenced by various environmental factors. The following table summarizes key methylation patterns and their functional consequences:

| Methylation Pattern | Genomic Context | Functional Consequence | Disease Association |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypermethylation | Promoter CpG Islands | Gene silencing/suppression | Tumor suppressor gene inactivation in cancer [4] [5] |

| Global Hypomethylation | Repetitive elements, gene bodies | Genomic instability, oncogene activation | Cancer progression, chromosomal instability [6] [5] |

| Tissue-Specific Differential Methylation | Enhancers, CpG island shores | Cell type-specific gene expression | Normal cellular differentiation and function [4] [7] |

| Imprinting Control Region Methylation | Imprinted genes | Monoallelic gene expression | Imprinting disorders (Prader-Willi, Angelman syndromes) [5] |

In cancer, these patterns are frequently disrupted, with tumors typically displaying both genome-wide hypomethylation and localized hypermethylation of specific promoter CpG islands, particularly those associated with tumor suppressor genes [6] [5]. These alterations often occur early in tumorigenesis and remain stable throughout tumor evolution, making them excellent biomarkers for detection and monitoring [6].

Analytical Methods for DNA Methylation Assessment

The gold-standard method for DNA methylation analysis is bisulfite conversion, where treatment with bisulfite reagents converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils while leaving methylated cytosines unchanged [4]. Post-conversion, various downstream applications can be employed:

Genome-Wide Methylation Profiling Methods

| Method | Resolution | Coverage | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) | Single-base | Entire genome | Discovery-based studies, comprehensive methylome mapping [6] [9] | Gold standard for completeness | High cost, computational demands [6] |

| Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS) | Single-base | CpG-rich regions | Cost-effective methylome profiling [4] [9] | Focuses on informative regions, cost-effective | Incomplete genome coverage [4] |

| Infinium Methylation BeadChip | Single CpG site | Predefined CpG sites (450K-850K) | Large cohort studies, clinical biomarker validation [9] [10] | High-throughput, cost-effective for large samples | Limited to predefined sites [9] |

| Enzymatic Methyl-Sequencing (EM-seq) | Single-base | Entire genome | Chemical-free conversion, superior DNA preservation [6] | Better DNA integrity than bisulfite | Newer method, less established [6] |

Targeted Methylation Analysis Methods

For validation studies and clinical applications, particularly with limited samples like cfDNA, targeted approaches are preferred:

- Methylation-Specific PCR (qMSP): Quantitative method using primers specific to methylated sequences after bisulfite conversion [8].

- Digital Droplet PCR (ddPCR): Absolute quantification of methylated molecules with high sensitivity, suitable for low-abundance cfDNA [10].

- Multiplex ddPCR (mddPCR): Simultaneous detection of multiple methylation markers using different fluorescent probes, enhancing diagnostic sensitivity [10].

- Targeted Bisulfite Sequencing: Focused sequencing of regions of interest using designed capture probes [4].

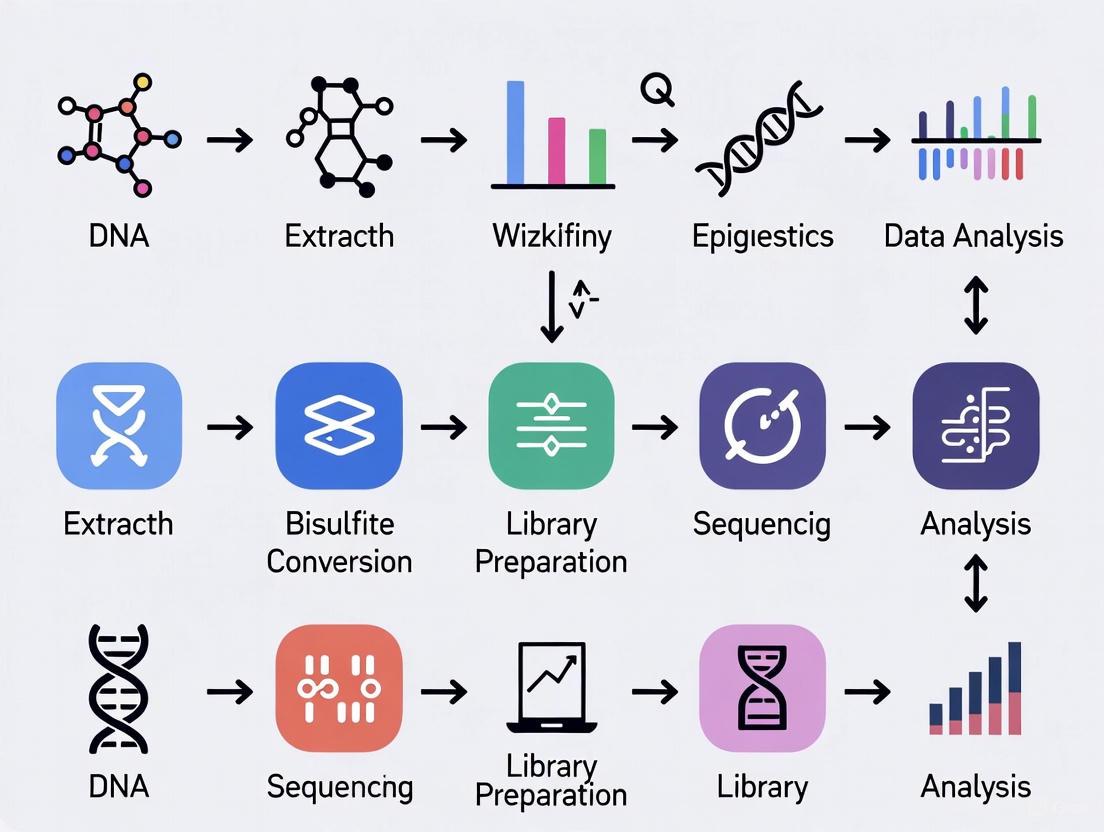

Workflow for Cell-Free DNA Methylation Biomarker Discovery

The following diagram outlines a comprehensive workflow for cfDNA methylation biomarker discovery and validation:

Phase 1: Biomarker Discovery

The initial discovery phase requires well-characterized sample cohorts including case and appropriate control groups [6]. For cfDNA methylation biomarker discovery, considerations should include:

- Liquid Biopsy Source Selection: Blood (plasma) is most common, but local fluids (urine, saliva, CSF) may offer higher biomarker concentration for specific cancers [6].

- Control Group Design: Must include appropriate controls (healthy individuals, benign conditions, other cancer types) to ensure biomarker specificity [6] [10].

- High-Throughput Methylation Profiling: Utilize WGBS, RRBS, or methylation arrays to identify differentially methylated regions (DMRs) or CpG sites [9] [10].

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Identify DMRs with significant methylation differences between groups, then filter against public databases (e.g., TCGA) to select markers with tissue specificity and minimal background interference [10].

Phase 2: Assay Development and Validation

Promising methylation markers from the discovery phase must be translated into sensitive detection assays suitable for cfDNA:

- Multiplex Assay Design: Develop multiplex ddPCR or targeted NGS panels for simultaneous detection of multiple methylation markers to enhance sensitivity [10].

- Analytical Validation: Establish sensitivity, specificity, and limit of detection using standard curves and control samples [8] [10].

- Clinical Validation: Assess diagnostic performance in independent patient cohorts, calculating AUC, sensitivity, and specificity [10].

- Integration with Other Modalities: Combine methylation markers with existing clinical tests (e.g., imaging, other biomarkers) to enhance overall diagnostic performance [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Category | Specific Products/Technologies | Function in Methylation Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits | EZ DNA Methylation kits, Epitect Bisulfite kits | Convert unmethylated cytosine to uracil while preserving methylated cytosine [4] |

| Methylation-Specific Enzymes | Restriction enzymes (e.g., DpnI), DNMT inhibitors | Selective digestion of methylated DNA or pharmacological modulation of methylation [11] |

| Library Preparation Kits | Illumina DNA Prep, Accel-NGS Methyl-Seq | Prepare bisulfite-converted DNA for next-generation sequencing [4] [9] |

| Targeted Capture Panels | SureSelect Methyl-Seq, Twist Methylation Panels | Enrich regions of interest for targeted bisulfite sequencing [4] |

| Methylation qPCR/dPCR Reagents | ddPCR Supermix for probes, MethylLight reagents | Quantitative detection of methylation at specific loci [10] |

| Whole Genome Amplification Kits | REPLI-g, GenomePlex | Amplify limited DNA samples while preserving methylation patterns [8] |

| Methylated DNA Standards | Fully methylated genomic DNA, synthetic methylated oligos | Positive controls for assay development and validation [10] |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Machine Learning in Methylation Analysis

The complexity of genome-wide methylation data has driven the adoption of machine learning approaches. Supervised methods like support vector machines and random forests can classify cancer subtypes based on methylation profiles, while deep learning models such as MethylGPT and CpGPT enable pretraining on large methylome datasets for enhanced prediction of clinical outcomes [9].

Multi-Omics Integration

Integrating cfDNA methylation data with genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic information provides a more comprehensive view of disease states. This approach enhances diagnostic and predictive potential beyond single-platform analyses [8] [9].

Emerging Technologies

Third-generation sequencing technologies like Oxford Nanopore and PacBio SMRT sequencing enable direct detection of DNA methylation without bisulfite conversion, preserving DNA integrity and providing long-range epigenetic information [6] [9]. Single-cell methylation profiling techniques (scBS-seq, sci-MET) reveal cellular heterogeneity in complex tissues and tumors [9].

DNA methylation serves as a critical regulatory mechanism with extensive applications in basic research and clinical diagnostics. The workflow for cfDNA methylation biomarker discovery encompasses careful sample selection, comprehensive methylome profiling, bioinformatic analysis, and rigorous validation using sensitive targeted assays. As technologies advance and computational methods become more sophisticated, DNA methylation-based biomarkers show increasing promise for non-invasive disease detection, monitoring, and personalized treatment strategies. The integration of methylation analyses with other omics data and the development of novel computational approaches will further enhance our understanding of epigenetic regulation in health and disease.

Why Methylation? Advantages over Genetic Mutations for Cancer Biomarkers

DNA methylation is an epigenetic modification involving the addition of a methyl group to the 5-carbon position of cytosine residues, primarily within CpG dinucleotides, forming 5-methylcytosine (5mC) without altering the underlying DNA sequence [12] [13]. This reversible modification plays crucial roles in regulating gene expression, genomic imprinting, and maintaining chromosomal stability under physiological conditions [13]. In oncology, DNA methylation has emerged as a powerful biomarker class that addresses several limitations inherent to genetic mutation-based approaches. While genetic mutations involve permanent changes to the DNA sequence itself, epigenetic alterations represent dynamic regulatory mechanisms that respond to environmental influences and disease states [9].

The clinical application of DNA methylation biomarkers leverages their unique biological characteristics, which include early emergence in tumorigenesis, stability in circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA), tissue-specific patterns, and quantitative nature that reflects disease burden [12] [6]. Unlike genetic mutations that can be heterogeneously distributed throughout tumors, DNA methylation patterns demonstrate remarkable consistency across tumor subtypes, making them particularly valuable for diagnostic applications [14]. Furthermore, technological advances in detection methodologies, from bisulfite sequencing to microarray platforms, have enabled precise quantification of methylation states at single-base resolution, facilitating the translation of methylation biomarkers from research settings to clinical practice [12] [15].

Key Advantages of DNA Methylation Biomarkers

Biological and Technical Superiority

DNA methylation biomarkers offer distinct advantages across multiple dimensions of cancer biomarker development and application. These benefits stem from both fundamental biological characteristics and practical technical considerations for clinical implementation.

Table 1: Comparative Advantages of DNA Methylation vs. Genetic Mutation Biomarkers

| Aspect | DNA Methylation Biomarkers | Genetic Mutation Biomarkers |

|---|---|---|

| Stability | Enhanced resistance to degradation in cfDNA; half-life of minutes to hours [6] | Rapid degradation; challenging detection in early-stage cancers [6] |

| Temporal Occurrence | Emerge early in tumorigenesis; present in precancerous stages [12] [6] | Typically accumulate throughout cancer progression |

| Pattern Distribution | Tissue-specific patterns enable tissue-of-origin identification [6] [14] | Lacks consistent tissue-specific signature |

| Analytical Nature | Quantitative changes across multiple genomic regions [12] | Typically qualitative (presence/absence of mutations) |

| Dynamic Range | Broad dynamic range reflecting tumor burden [6] | Limited by mutant allele fraction |

| Clinical Utility | Suitable for early detection, prognosis, and monitoring [12] [14] | Primarily useful for targeted therapies and monitoring |

The stability of DNA methylation in cell-free DNA represents a particularly significant advantage for liquid biopsy applications. Methylated DNA fragments demonstrate relative enrichment within the cfDNA pool due to nucleosome interactions that protect them from nuclease degradation [6]. This inherent stability provides a practical benefit during sample collection, storage, and processing, especially compared to more labile molecules such as RNA [6]. Furthermore, cancer-specific DNA methylation patterns typically emerge during early tumorigenesis and remain stable throughout tumor evolution, making them ideal biomarkers for early detection when therapeutic interventions are most effective [6].

Clinical Application Advantages

From a clinical perspective, DNA methylation biomarkers enable several applications that are challenging with genetic mutation-based approaches:

Multi-Cancer Early Detection: Methylation-based classifiers can simultaneously screen for multiple cancer types from a single blood sample while predicting the tissue of origin, a capability recently demonstrated in large studies like PATHFINDER, which identified a cancer signal in 1.4% of asymptomatic adults [14].

Tumor Classification and Diagnosis: DNA methylation profiling has revolutionized the diagnosis of central nervous system tumors, soft tissue sarcomas, and other neoplasms where traditional histopathology faces limitations. For example, methylation-based classification altered the initial diagnosis in 12% of CNS tumor cases and provided definitive diagnoses in approximately 50% of challenging cases [14].

Risk Stratification: In conditions like juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML), DNA methylation subgroups serve as powerful independent prognostic factors, outperforming traditional clinical and genetic markers for outcome prediction [14].

DNA Methylation Biomarkers in Clinical Research

Pan-Cancer Methylation Signatures

Recent research has identified methylation biomarkers capable of detecting multiple cancer types with high sensitivity and specificity, particularly for malignancies characterized by low five-year survival rates. Integrated analysis of genome-wide DNA methylation profiles has revealed key biomarkers across pancreatic (10% five-year survival), esophageal (20%), liver (20%), lung (21%), and brain (27%) cancers [16]. Among these, ALX3, HOXD8, IRX1, HOXA9, HRH1, PTPRN2, TRIM58, and NPTX2 have emerged as important methylation biomarkers showing significant differential methylation across all five cancer types [16]. The combination of ALX3, NPTX2, and TRIM58 from distinct functional groups achieved 93.3% accuracy in validating the ten most common cancers, including the initial five low-survival-rate cancer types [16].

Tissue-Specific and Cancer-Specific Methylation Markers

Comprehensive methylation analyses have identified numerous cancer-specific methylation markers with demonstrated clinical utility across different sample types, including tissues and liquid biopsies.

Table 2: Validated DNA Methylation Biomarkers for Cancer Diagnosis

| Cancer Type | Methylation Biomarkers | Sample Type | Performance | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer | TRDJ3, PLXNA4, KLRD1, KLRK1 | PBMC, Tissue, Blood | Sensitivity: 93.2%, Specificity: 90.4% | [12] |

| Colorectal Cancer | SDC2, SFRP2, SEPT9 | Tissue, Feces, Blood | Sensitivity: 86.4%, Specificity: 90.7% (ColonSecure study) | [12] |

| Lung Cancer | SHOX2, RASSF1A, PTGER4 | Tissue, Blood, Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid | High sensitivity in liquid biopsy | [12] |

| Bladder Cancer | CFTR, SALL3, TWIST1 | Urine | Superior to plasma-based detection | [12] |

| Esophageal Cancer | OTOP2, KCNA3 | Tissue, Blood | AUC: 96.6% | [12] |

| Hereditary Breast Cancer | cg47630224-MSH2, cg23652916-PALB2 | Peripheral Blood | 3-fold increased risk (AUC: 0.929) | [17] |

The development of these biomarkers leverages the fundamental roles of DNA methylation in cancer pathogenesis. Promoter hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes leads to transcriptional silencing and loss of tumor suppressor function, while global hypomethylation can induce chromosomal instability and oncogene activation [13]. These alterations occur consistently across cancer types and can be detected in various sample matrices, enabling flexible diagnostic approaches tailored to clinical needs.

Experimental Workflows for Methylation Biomarker Discovery

Comprehensive Workflow for Methylation Biomarker Discovery

The process of identifying and validating DNA methylation biomarkers follows a structured pathway from sample collection through clinical implementation. The following diagram illustrates this comprehensive workflow:

Diagram Title: DNA Methylation Biomarker Discovery Workflow

Sample Collection and Processing Protocols

Sample Collection for Liquid Biopsy Applications

For blood-based liquid biopsy studies, collect peripheral blood into specialized cfDNA preservation tubes (e.g., cfDNA/cfRNA Preservative Norgen tubes). Process samples within 2 hours of collection using a standardized centrifugation protocol [18]:

- Initial centrifugation: 1,600 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C to separate plasma from cellular components

- Secondary centrifugation: 16,000 × g at room temperature to remove remaining cell debris

- Storage: Aliquot supernatant and store at -80°C until DNA extraction

For tissue samples, snap-freeze in liquid nitrogen or preserve in appropriate nucleic acid stabilization reagents. The selection of sample type should align with clinical objectives, with liquid biopsies offering non-invasive repeated sampling capabilities, while tissue biopsies provide comprehensive molecular profiling from the primary tumor [12].

DNA Extraction and Bisulfite Conversion Protocol

Extract cfDNA using specialized kits designed for low-concentration samples (e.g., NextPrep-Mag cfDNA isolation kit). Quantify DNA using fluorescence-based methods (e.g., Qubit dsDNA HS assay) [18].

For bisulfite conversion, use commercial kits (e.g., EZ DNA methylation-lightning kit) with the following protocol [18]:

- Denaturation: Incubate DNA in conversion reagent at 98°C for 10 minutes

- Conversion: Incubate at 54°C for 30-60 minutes

- Desalting and purification: Bind converted DNA to provided columns, wash, and elute

- Quality assessment: Verify conversion efficiency through control reactions

Alternative enzymatic conversion methods (e.g., using EM-seq kits) reduce DNA fragmentation and are particularly advantageous for limited samples [15].

Methylation Profiling and Analysis Methods

Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) Protocol

WGBS remains the gold standard for comprehensive methylation profiling at single-base resolution [15]:

- Library preparation: Use enzymatic methyl-seq kits (e.g., NEBNext Enzymatic Methyl-seq Kit) following manufacturer's instructions

- Library quantification: Use fluorescence-based methods (e.g., Qubit dsDNA HS assay)

- Sequencing: Perform on appropriate platforms (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq 6000) with 2×150 bp paired-end reads at minimum 30× coverage

- Quality control: Assess library size distribution and concentration before sequencing

Targeted Methylation Analysis Protocol

For validation studies or clinical applications, targeted approaches offer cost-effective solutions:

- Primer design: Design bisulfite-conversion specific primers for regions of interest

- Amplification: Perform PCR with bisulfite-converted DNA as template

- Analysis: Utilize pyrosequencing, digital PCR, or next-generation sequencing for quantitative assessment

- Validation: Confirm assay performance with positive and negative methylation controls

Bioinformatic Analysis Workflow

Process sequencing data through established pipelines [15]:

- Quality control and trimming: Use FastQC and trimmers to remove adapters and low-quality bases

- Alignment: Perform conversion-aware alignment using tools like Bismark, Bismark, or BWA-meth

- Methylation calling: Extract methylation states for individual CpG sites

- Differential methylation analysis: Identify significantly differentially methylated regions using tools like Seqmonk or methylSig

- Validation: Confirm findings in independent cohorts using targeted methods

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Successful implementation of DNA methylation biomarker research requires specialized reagents, kits, and platforms optimized for various aspects of the workflow.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for DNA Methylation Biomarker Discovery

| Category | Specific Products/Kits | Application Purpose | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection | cfDNA/cfRNA Preservative Tubes (Norgen Biotek) | Blood sample stabilization | Preserves cfDNA integrity during storage/transport |

| DNA Extraction | NextPrep-Mag cfDNA Isolation Kit (PerkinElmer) | cfDNA extraction from plasma | Magnetic bead-based, optimized for low concentrations |

| Bisulfite Conversion | EZ DNA Methylation-Lightning Kit (Zymo Research) | Chemical conversion of unmethylated C to U | Rapid conversion (90 minutes), high recovery |

| Enzymatic Conversion | NEBNext Enzymatic Methyl-seq Kit | Bisulfite-free conversion | Reduced DNA fragmentation, better preservation |

| Library Prep | Accel-NGS Methyl-Seq Kit (Swift Bio) | Library preparation for sequencing | Adaptase technology, low input requirements |

| Targeted Analysis | PyroMark PCR Kit (Qiagen) | Targeted methylation analysis | Quantitative methylation measurement |

| Microarray Platform | Infinium HumanMethylationEPIC BeadChip | Genome-wide methylation screening | 850,000 CpG sites, cost-effective for large cohorts |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Bismark, MethylKit, SeSAMe | Data processing and analysis | Specialized for bisulfite sequencing data |

Integration with Machine Learning and Advanced Analytics

The quantitative nature of DNA methylation data makes it particularly amenable to machine learning approaches for biomarker development. Several strategies have demonstrated significant utility in translating methylation patterns into clinically actionable tools [9]:

Conventional Machine Learning: Support vector machines, random forests, and gradient boosting algorithms have been successfully employed to classify tumor subtypes, predict outcomes, and select informative CpG sites from large feature sets. These methods can be streamlined through Automated Machine Learning (AutoML) platforms to create robust classifiers applicable to clinical settings [9].

Deep Learning Approaches: Multilayer perceptrons and convolutional neural networks capture nonlinear interactions between CpGs and genomic context, enabling sophisticated tumor subtyping, tissue-of-origin classification, and survival risk evaluation. Recently, transformer-based foundation models pretrained on extensive methylome datasets (e.g., MethylGPT, CpGPT) have demonstrated robust cross-cohort generalization and contextually aware CpG embeddings [9].

Multi-Cancer Early Detection: The combination of targeted methylation assays with machine learning enables early detection of multiple cancer types from plasma cell-free DNA, demonstrating high specificity and accurate tissue-of-origin prediction that enhances organ-specific screening programs [9] [14].

DNA methylation biomarkers represent a powerful paradigm in cancer diagnostics, offering distinct advantages over genetic mutation-based approaches through their early emergence in tumorigenesis, stability in circulation, tissue-specific patterns, and quantitative nature. The structured workflow for methylation biomarker discovery—encompassing appropriate sample collection, conversion-based profiling technologies, and advanced computational analysis—enables the development of robust clinical assays with applications in early detection, tumor classification, and treatment monitoring.

As technologies continue to evolve, particularly in the domains of single-cell methylation profiling, long-read sequencing, and machine learning integration, the clinical utility of DNA methylation biomarkers will expand further. The ongoing translation of these epigenetic tools from research settings to routine clinical practice holds significant promise for advancing personalized oncology and improving patient outcomes through earlier detection and more precise molecular classification of malignancies.

Within the evolving paradigm of liquid biopsy-based diagnostics, cell-free DNA (cfDNA) methylation has emerged as a cornerstone for non-invasive cancer detection and management. For a methylation biomarker to be successfully translated from a research finding to a clinically actionable tool, it must exhibit a set of fundamental characteristics that ensure reliability and utility in real-world settings [19]. These characteristics—high specificity for the target disease, inherent stability in circulation, and early appearance during tumorigenesis—form the essential triad that defines an ideal biomarker [20] [6]. This application note delineates these core characteristics, supported by quantitative data and experimental evidence, and provides detailed protocols to guide their systematic evaluation in biomarker discovery workflows. The focus is on creating a robust framework that researchers can employ to validate candidate markers effectively, thereby enhancing the pipeline for clinical translation.

Core Characteristics of an Ideal Methylation Biomarker

The evaluation of a DNA methylation biomarker's potential hinges on three interdependent pillars. The diagram below illustrates the logical relationship between these core characteristics and their collective contribution to clinical utility.

Specificity

A prime characteristic of an ideal methylation biomarker is its high specificity for a particular cancer type. This refers to the biomarker's ability to differentiate tumor DNA from normal cfDNA derived from healthy cells, thereby minimizing false-positive results [6]. Cancer-specific methylation patterns typically manifest as hypermethylation of CpG islands in promoter regions of tumor suppressor genes, leading to their silencing, coupled with global hypomethylation in other genomic regions which can induce genomic instability [20] [6]. This aberrant pattern is distinct from the methylation landscape of healthy tissues.

Specificity is quantitatively measured as the proportion of individuals without the disease who test negative. Panels combining multiple methylation markers often achieve higher specificity than single-marker assays by capturing a unique epigenetic signature of the malignancy [21]. For instance, a meta-analysis of cfDNA methylation for lung cancer detection reported a pooled specificity of 86%, indicating a strong ability to correctly identify non-cancerous cases [21]. Key genes frequently investigated for their cancer-specific hypermethylation in liquid biopsies include SHOX2, RASSF1A, and APC [21] [22].

Stability

The biological and analytical stability of methylation biomarkers is another critical attribute. DNA methylation is a stable epigenetic mark that is faithfully replicated during cell division and is less prone to random fluctuations compared to RNA transcripts or some proteins [6]. Once established in a tumor, these patterns are clonally propagated, providing a consistent signal for detection [20].

Furthermore, methylated cfDNA fragments exhibit enhanced stability in the bloodstream. Evidence suggests that nucleosomes protect methylated DNA from nuclease degradation, leading to a relative enrichment of these fragments in the total cfDNA pool [6]. This inherent stability is crucial for practical clinical application, as it allows for robustness during sample collection, storage, and processing. The half-life of cfDNA is short (minutes to a few hours), yet the methylation state remains a durable indicator of its tissue of origin, making it more reliable than labile biomarkers like RNA [6] [19]. This stability is a key advantage for developing reproducible and robust clinical diagnostic tests.

Early Appearance

Perhaps the most significant advantage of DNA methylation as a biomarker is its early onset during tumorigenesis. Epigenetic alterations, including promoter hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes, are often initiating events in cancer development, occurring even before genetic mutations accumulate and clinical symptoms manifest [20] [6] [22]. This property makes methylation biomarkers exceptionally powerful for early-stage cancer screening, where the potential for curative intervention is highest.

The early appearance of methylation changes enables the detection of cancer when the tumor burden is minimal and the concentration of ctDNA in the blood is very low [19]. For example, methylation of genes like CDKN2A (p16) has been detected in sputum samples from high-risk individuals up to three years before a clinical diagnosis of lung cancer was made [22]. The ability to identify these early epigenetic shifts provides a critical window of opportunity for early intervention and significantly improves patient survival outcomes.

Table 1: Quantitative Diagnostic Performance of Selected Methylation Biomarkers in Liquid Biopsies

| Cancer Type | Methylation Marker(s) | Reported Sensitivity (%) | Reported Specificity (%) | Source / Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung Cancer | SHOX2, RASSF1A |

73 | 82 | Diagnostic model in plasma [20] |

| Lung Cancer | Various (e.g., RASSF1A, APC, SHOX2) |

54 (Pooled) | 86 (Pooled) | Meta-analysis of ccfDNA [21] |

| Breast Cancer | 8-marker panel via mddPCR | AUC: 0.856* | AUC: 0.856* | Differentiation from healthy controls [10] |

| Breast Cancer | 8-marker panel via mddPCR | AUC: 0.742* | AUC: 0.742* | Differentiation from benign tumors [10] |

| Ovarian Cancer | 15-gene signature (e.g., hypermethylated genes) | N/A | N/A | cfMeDIP-seq profiling [23] |

*Area Under the Curve (AUC) is a combined performance metric where 1 represents perfect classification and 0.5 represents no discriminative power.

Table 2: Key Methylated Genes as Illustrative Biomarkers Across Cancers

| Gene Symbol | Full Name | Primary Function | Methylation Change in Cancer | Potential Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHOX2 | Short Stature Homeobox 2 | Transcriptional factor, organ development | Hypermethylation | Lung cancer detection in plasma/sputum [20] [22] |

| RASSF1A | Ras Association Domain Family Member 1A | Tumor suppressor, apoptosis, Hippo pathway | Promoter Hypermethylation | Lung cancer diagnosis, increased in smokers [20] [22] |

| DAPK | Death-Associated Protein Kinase | Tumor suppressor, apoptosis promoter | Promoter Hypermethylation | Independent prognostic factor in lung cancer [20] |

| MGMT | O-6-Methylguanine-DNA Methyltransferase | DNA repair gene | Promoter Hypermethylation | Diagnostic marker in plasma/BLAF; associated with advanced stage [20] |

Experimental Protocols for Biomarker Evaluation

A rigorous, multi-phase workflow is essential for the discovery and validation of cfDNA methylation biomarkers. The following section outlines detailed protocols for the key stages of this process.

Biomarker Discovery and Analytical Validation Workflow

The journey from candidate identification to a clinically viable assay involves sequential steps of discovery, technical validation, and clinical verification, as outlined below.

Protocol: Multiplex ddPCR for Methylation Quantification in cfDNA

Multiplex droplet digital PCR (mddPCR) allows for the simultaneous, absolute quantification of multiple methylation markers from a limited cfDNA input, making it ideal for analytical validation and eventual clinical application [10].

1. Principle: The assay involves partitioning a bisulfite-converted cfDNA sample into thousands of nanoliter-sized droplets. Each droplet acts as an individual PCR reactor. Target-specific primers and TaqMan probes with different fluorescent dyes (e.g., FAM, VIC) enable the detection of multiple methylated loci in a single reaction. After amplification, the droplet reader counts the number of positive and negative droplets for each target, allowing for absolute quantification of the methylated DNA molecules without the need for a standard curve [10].

2. Reagents and Equipment:

- cfDNA Sample: Extracted from plasma (e.g., using QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit).

- Bisulfite Conversion Kit: (e.g., EZ DNA Methylation-Lightning Kit, Zymo Research).

- ddPCR Supermix for Probes (No dUTP).

- Primers and MGB TaqMan Probes specific for the bisulfite-converted sequence of the methylated target genes.

- Droplet Generator (QX200), T100 Thermal Cycler, and Droplet Reader (QX200) (Bio-Rad).

- QuantaSoft Analysis Pro Software (Bio-Rad).

3. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- A. Bisulfite Conversion: Convert 5-20 ng of input cfDNA according to the manufacturer's instructions. Elute in 40 µL of elution buffer.

- B. Reaction Setup: Prepare a 21 µL reaction mixture for each sample as follows [10]:

- 10 µL of ddPCR Supermix for Probes (No dUTP)

- Adjusted volumes of forward and reverse primers and FAM/VIC-labeled MGB TaqMan probes for each target (final concentrations typically 100-900 nM each)

- 5-6 µL of bisulfite-converted DNA template

- C. Droplet Generation: Transfer 20 µL of the reaction mixture to a DG8 cartridge. Add 70 µL of Droplet Generation Oil for Probes to the appropriate well. Place the cartridge in the QX200 Droplet Generator to create ~20,000 droplets.

- D. PCR Amplification: Carefully transfer the emulsified droplets to a 96-well PCR plate. Seal the plate and run the PCR on a thermal cycler with the following protocol [10]:

- Enzyme activation: 95°C for 10 minutes.

- 40 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 94°C for 30 seconds.

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 1 minute.

- Enzyme deactivation: 98°C for 10 minutes.

- Hold at 4°C. (Ramp rate: 2°C/second for all steps)

- E. Droplet Reading and Analysis: Place the plate in the QX200 Droplet Reader. The instrument will stream each droplet past a two-color optical detector. Analyze the data using QuantaSoft Analysis Pro software. Set fluorescence amplitude thresholds based on no-template control and positive control samples to distinguish positive (methylated) and negative (unmethylated) droplets.

4. Data Analysis:

The software provides the concentration (copies/µL) of each methylated target in the original reaction. The fraction of methylated alleles can be calculated as:

(Concentration of methylated target / Total DNA concentration) * 100

Statistical analysis (e.g., logistic regression) is then used to determine the optimal combination of markers and their cut-off values for distinguishing cancer cases from controls [10].

Protocol: Genome-Wide Methylation Profiling using cfMeDIP-seq

For the unbiased discovery of novel methylation biomarkers, cell-free methylated DNA immunoprecipitation sequencing (cfMeDIP-seq) is a powerful method that enriches for methylated DNA fragments without requiring bisulfite conversion, thereby preserving DNA integrity [23].

1. Principle: cfMeDIP-seq utilizes an antibody specific for 5-methylcytosine (5mC) to immunoprecipitate methylated DNA fragments from sheared cfDNA. The enriched methylated DNA is then prepared into a sequencing library, which is sequenced on a high-throughput platform. This allows for the genome-wide identification of differentially methylated regions (DMRs) between case and control samples [23].

2. Reagents and Equipment:

- Magnetic beads coupled with 5mC antibody.

- cfDNA samples (from patients and controls).

- Library preparation kit (e.g., NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit).

- Size selection beads (e.g., AMPure XP).

- High-sensitivity DNA assay kit (e.g., Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit).

- Sequencing platform (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq).

3. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- A. cfDNA Fragmentation and End-Repair: If necessary, fragment cfDNA to an average size of 150-200 bp via sonication. Repair the ends of the DNA fragments to create blunt ends.

- B. Immunoprecipitation: Incubate the repaired cfDNA with the 5mC antibody-bound magnetic beads. Wash the beads to remove unbound, non-methylated DNA. Elute the enriched methylated DNA from the beads.

- C. Library Preparation: Add sequencing adapters to the eluted methylated DNA and amplify the library with a limited number of PCR cycles. Perform size selection to retain library fragments of the desired length.

- D. Sequencing and Bioinformatic Analysis: Quantify the final library and pool for sequencing. Sequence to a sufficient depth (e.g., 20-50 million reads per sample). Align the sequenced reads to a reference genome (e.g., hg38) and call DMRs using bioinformatic tools like MEDIPS or similar. Gene ontology (GO) and pathway enrichment analysis (e.g., with

clusterProfilerin R) can reveal the biological relevance of the hypermethylated genes [23].

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Kit | Primary Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Circulating Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit (e.g., QIAamp CNA Kit) | Isolate high-quality cfDNA from plasma/serum. | Maximize yield from low-volume samples; minimize contamination by genomic DNA. |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kit | Convert unmethylated cytosines to uracils, leaving methylated cytosines unchanged. | High conversion efficiency is critical; optimised for low-input, fragmented DNA. |

| Methylation-Specific qPCR/ddPCR Assays | Target-specific quantification of methylated alleles. | Requires careful design of primers/probes for bisulfite-converted sequences. |

| Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) Kit | Unbiased, base-resolution methylation mapping across the genome. | High cost and data complexity; requires high DNA input. |

| cfMeDIP-seq Kit | Antibody-based enrichment and sequencing of methylated cfDNA. | No bisulfite conversion; good for fragmented DNA; resolution is lower than WGBS. |

| Methylation Microarrays (e.g., Illumina EPIC) | Interrogation of methylation at pre-defined CpG sites. | Cost-effective for large cohorts; limited to covered CpG sites. |

| 5-methylcytosine (5mC) Antibody | Core reagent for MeDIP and related enrichment protocols. | Specificity and lot-to-lot consistency are paramount. |

Liquid biopsy has emerged as a minimally invasive alternative to traditional tissue biopsies, enabling real-time monitoring of tumor dynamics and providing a comprehensive view of tumor heterogeneity [24]. While the "liquid" in liquid biopsy most commonly refers to blood, numerous other biological fluids can be utilized as valuable sources of tumor-derived material [25] [26]. The selection of an appropriate biofluid is critical for successful cell-free DNA (cfDNA) methylation biomarker discovery, as it directly impacts biomarker concentration, sample purity, and clinical applicability [6]. These fluids contain various biomarkers including circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), circulating tumor cells (CTCs), extracellular vesicles (EVs), and non-coding RNAs, each offering unique insights into tumor biology [25] [24].

The circulatory system reaches virtually every tissue in the body, allowing blood to serve as a reservoir for cancer-specific material shed from tumors regardless of their anatomic location [6]. However, depending on their anatomical location, various cancer types shed material into nearby body fluids other than blood, including urine, saliva, cerebrospinal fluid, bile, stool, pleural effusions, peritoneal fluid, and seminal fluid [6] [26]. In contrast to the systemic nature of blood, these local body fluids often offer distinct advantages, including higher biomarker concentration and reduced background noise from other tissues [6]. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of these liquid biopsy sources with specific application to workflow design for cfDNA methylation biomarker discovery research.

Table 1: Characteristics of Major Liquid Biopsy Sources for cfDNA Methylation Biomarker Research

| Biofluid Source | Invasiveness of Collection | Relative ctDNA Yield | Key Advantages | Primary Cancer Applications | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood (Plasma) | Minimally invasive (venipuncture) | Low to moderate (highly diluted) | Systemic circulation captures biomarkers from all tumor sites [6] | Pan-cancer [25] [6] | High background cfDNA from hematopoietic cells [6] |

| Urine | Non-invasive | Variable (high for urological cancers) | Large volumes available; ideal for repeated sampling [26] | Bladder, prostate, renal cancers [6] | Lower ctDNA yield for non-urological cancers [6] |

| Saliva | Non-invasive | Variable (high for head/neck cancers) | Easiest to collect without specialist training [26] | Head and neck cancers, NSCLC [26] | Contamination with food debris; bacterial DNA |

| Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) | Highly invasive (lumbar puncture) | High for CNS malignancies | ctDNA present in larger amounts than plasma [26] | Central nervous system tumors [26] | Invasive collection procedure |

| Stool | Non-invasive | High for colorectal cancers | Direct contact with gastrointestinal tumors | Colorectal cancer [6] | Complex composition; inhibitory substances |

| Bile | Highly invasive (medical procedure) | High for biliary tract cancers | Superior mutation detection compared to plasma [6] | Biliary tract cancers, cholangiocarcinoma [6] | Highly invasive collection; limited availability |

Technical Considerations for Source Selection

Table 2: Technical Processing Requirements for Different Biofluid Types

| Parameter | Blood (Plasma) | Urine | Saliva | CSF | Stool |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommended Volume | 7.5-10 mL [27] | 10-50 mL | 1-5 mL | 1-5 mL | 1-10 g |

| Key Pre-analytical Considerations | Use of EDTA/streck tubes; rapid processing to prevent cell lysis [6] | Stabilization additives; centrifugation to remove cells | Protease inhibitors; rapid processing | Less complex; minimal stabilization needed | Homogenization; inhibitor removal |

| DNA Extraction Method | QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit (Qiagen) [28] | Phenol-chloroform-ethanol or commercial kits | Commercial kits with inhibitor removal | Standard plasma protocols | Specialized kits for stool |

| Typical cfDNA Concentration | Highly variable (0.1-10% ctDNA fraction) [24] | Higher for urological cancers [6] | Variable; tumor-type dependent | High for CNS malignancies [26] | High for colorectal cancers [6] |

| Major Contaminants | Genomic DNA from lysed blood cells [6] | Degradation products; PCR inhibitors | Bacterial DNA; food particles | Minimal | PCR inhibitors; bacterial DNA |

Experimental Protocols for cfDNA Methylation Analysis

Sample Collection and Processing Workflow

Figure 1: Universal sample collection and processing workflow for different liquid biopsy sources. Specific protocols must be optimized for each biofluid type to ensure cfDNA stability and prevent degradation.

cfDNA Extraction and Quality Control Protocol

Materials:

- QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit (Qiagen) [28]

- Phenol-chloroform-ethanol (alternative method) [28]

- Qubit fluorometer or similar quantification system

- Bioanalyzer High Sensitivity DNA Kit or TapeStation

Procedure:

- Sample Thawing: Thaw frozen plasma/urine/saliva/CSF samples on ice or at 4°C

- cfDNA Extraction: Follow manufacturer's protocol for the QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit with the following modifications:

- For urine samples: Add 5 μL of carrier RNA to improve yield

- For saliva samples: Pre-treat with hyaluronidase to reduce viscosity

- For stool samples: Use specialized stool DNA extraction kits

- Elution: Elute DNA in 20-30 μL of nuclease-free water or the provided elution buffer

- Quantification: Quantify DNA using Qubit fluorometer with dsDNA HS assay kit

- Quality Control: Assess fragment size distribution using Bioanalyzer High Sensitivity DNA Kit

DNA Methylation Analysis Workflow

Figure 2: Comprehensive DNA methylation analysis workflow from discovery to clinical application. Discovery phase utilizes genome-wide methods, while validation employs targeted approaches suitable for liquid biopsy samples with limited DNA input.

Bisulfite Conversion and Sequencing Protocol

Reagents:

- EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research) or equivalent

- Sodium bisulfite solution

- DNA cleanup columns

Bisulfite Conversion Procedure:

- DNA Input: Use 5-50 ng of extracted cfDNA (volume adjustment may be needed for low-concentration samples)

- Conversion: Incubate DNA with sodium bisulfite solution using the following thermal cycler program:

- 98°C for 10 minutes (denaturation)

- 64°C for 2.5 hours (conversion)

- 4°C hold (short-term storage)

- Cleanup: Purify converted DNA using provided columns according to manufacturer's instructions

- Elution: Elute in 10-20 μL of nuclease-free water

- Conversion Efficiency Check: Include unmethylated and fully methylated control DNA in each batch

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Library Prep: Use commercial bisulfite sequencing library preparation kits

- Amplification: 10-12 cycles of PCR amplification

- Quality Control: Validate library quality using Bioanalyzer

- Sequencing: Perform on appropriate platform (Illumina for WGBS/ RRBS; PacBio/ Oxford Nanopore for EM-seq)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for cfDNA Methylation Biomarker Discovery

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Considerations for Liquid Biopsies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood Collection Tubes | EDTA tubes, Streck Cell-Free DNA BCT tubes | Cellular genomic DNA contamination prevention [6] | Streck tubes allow longer processing windows (up to 3 days) |

| cfDNA Extraction Kits | QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit (Qiagen) [28], QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen) [28] | Isolation of high-quality cfDNA from various biofluids | Carrier RNA addition improves yields from dilute samples (e.g., urine) |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits | EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research), Epitect Bisulfite Kit (Qiagen) | Convert unmethylated cytosines to uracils while preserving methylated cytosines | Optimize for low-input DNA typical of liquid biopsies |

| Methylation-Specific PCR Reagents | Quantitative MSP primers/probes, methylation-independent control assays | Targeted validation of candidate methylation biomarkers | Design amplicons <150bp to accommodate fragmented cfDNA |

| Whole-Genome Amplification | REPLI-g Advanced DNA Single Cell Kit (Qiagen) | Amplify limited cfDNA for multiple assays | Introduces amplification bias; use minimally |

| DNA Quantitation Systems | Qubit fluorometer, Bioanalyzer, TapeStation | Accurate quantification and quality assessment of fragmented cfDNA | Fluorometric methods preferred over spectrophotometry for fragmented DNA |

| Bisulfite Sequencing Kits | Accel-NGS Methyl-Seq DNA Library Kit (Swift Biosciences), Pico Methyl-Seq Library Kit | Library preparation for genome-wide methylation analysis | Specifically optimized for low-input bisulfite-converted DNA |

Source-Specific Methodological Considerations

Blood-Based Liquid Biopsies

Blood remains the most extensively characterized liquid biopsy source, with plasma being preferred over serum due to less contamination with genomic DNA from lysed cells and higher stability of ctDNA [6]. The diagnostic sensitivity of blood-based liquid biopsies is directly influenced by the ctDNA fraction, which varies significantly across cancer types and stages [6]. In early-stage disease, the low ctDNA fraction presents a substantial challenge for methylation-based detection [6].

Protocol Optimization for Blood:

- Process samples within 2 hours of collection when using EDTA tubes, or within 3 days with Streck tubes

- Perform double centrifugation (1600 × g for 10 minutes, then 16,000 × g for 10 minutes) to remove cells and debris

- Use plasma rather than serum to minimize background wild-type DNA [6]

- Aliquot plasma before freezing to avoid freeze-thaw cycles

Urine-Based Liquid Biopsies

Urine is particularly valuable for urological cancers, with studies demonstrating significantly higher sensitivity for detecting bladder cancer mutations in urine compared to plasma (87% in urine versus 7% in plasma) [6]. For non-urological cancers, urine still offers utility but with lower ctDNA yields [6].

Protocol Optimization for Urine:

- Collect first-morning void for highest cellular content

- Process within 4 hours of collection or use stabilization buffers

- Centrifuge at 2000 × g for 10 minutes to remove cells and debris, followed by high-speed centrifugation (16,000 × g for 10 minutes) to collect cfDNA

- Concentrate large urine volumes (50-100 mL) using centrifugal filters when needed

Saliva-Based Liquid Biopsies

Saliva collection is exceptionally non-invasive and can be performed without specialist training, making it ideal for serial monitoring and potential point-of-care testing [26]. Saliva is particularly rich in biomarkers for head and neck cancers, but has also shown utility for less obvious tumor types like NSCLC [26].

Protocol Optimization for Saliva:

- Collect saliva before eating or brushing teeth to reduce food debris and bleeding

- Use DNA/RNA stabilizing buffers immediately after collection

- Centrifuge at 2600 × g for 10 minutes to separate supernatant from cellular fraction

- Treat with hyaluronidase if sample is viscous

CSF and Other Specialized Fluids

CSF offers exceptional biomarker concentration for central nervous system tumors, with ctDNA present in larger amounts than in plasma [26]. Similarly, bile has emerged as a promising liquid biopsy source for biliary tract cancers, often outperforming plasma in detecting tumor-related somatic mutations [6].

Protocol Optimization for CSF:

- Process CSF samples immediately after collection when possible

- Centrifuge at 16,000 × g for 10 minutes to remove cells

- Aliquot carefully to avoid unnecessary freeze-thaw cycles

- Note that CSF typically requires less input volume for downstream applications due to higher ctDNA fraction

The selection of an appropriate liquid biopsy source is a critical first step in designing successful cfDNA methylation biomarker discovery workflows. While blood remains the most versatile source applicable to multiple cancer types, local fluids often provide superior sensitivity for cancers in proximity to these biofluids. The future of liquid biopsy likely lies in multi-analyte approaches that combine methylation analysis with other molecular features such as mutations, fragmentomics, and protein biomarkers. As technological advances continue to improve the sensitivity of methylation detection, particularly for early-stage cancers with low ctDNA fractions, the strategic selection of biofluid sources will remain paramount to successful biomarker development and clinical translation.

From Sample to Data: A Guide to Methylation Profiling Technologies and Workflows

In the evolving landscape of liquid biopsy research, cell-free DNA (cfDNA) has emerged as a transformative biomarker source for minimally invasive disease detection and monitoring. The analysis of cfDNA methylation patterns offers particularly promising avenues for cancer detection, prognosis, and treatment monitoring due to the intrinsic characteristics of DNA methylation being more prevalent, pervasive, and cell-type-specific than genomic alterations [29]. The pre-analytical phase—encompassing sample collection, processing, and storage—represents the most critical determinant of data quality and experimental reproducibility in cfDNA methylation workflows. Variations in these initial steps can profoundly impact downstream molecular analyses, potentially introducing biases that compromise the validity of methylation-based biomarkers [29] [30]. This protocol details standardized procedures for cfDNA sample handling specifically optimized for methylation biomarker discovery research, providing researchers with a framework to minimize technical artifacts and maximize analytical sensitivity.

Liquid Biopsy Source Selection

The choice of biofluid source significantly influences cfDNA yield, quality, and biomarker concentration. Selection should be guided by the target pathology and anatomical considerations to optimize the signal-to-noise ratio for methylation biomarkers.

Table 1: Comparison of Liquid Biopsy Sources for cfDNA Methylation Analysis

| Biofluid Source | Advantages | Limitations | Primary Cancer Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood Plasma | Systemically circulates through all tissues; easily accessible; well-established protocols [6] | High dilution of tumor-derived signal; complex background from hematopoietic cells [6] | Pan-cancer applications (e.g., colorectal, breast, lung) [6] [10] | Preferred over serum due to less contamination from lysed cells and higher ctDNA stability [6] |

| Urine | Non-invasive collection; proximity to urological organs; higher biomarker concentration for urinary tract cancers [6] | Lower ctDNA from prostate and renal cancers compared to bladder cancer [6] | Bladder cancer (e.g., TERT mutations: 87% sensitivity in urine vs. 7% in plasma) [6] | Particularly effective for bladder cancer where tumors directly contact urine [6] |

| Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) | Direct contact with CNS; reduced background noise [6] | Invasive collection procedure | Brain tumors [6] | Outperforms plasma for detecting CNS malignancies [6] |

| Bile | High local concentration for biliary tract cancers [6] | Requires specialized clinical access | Biliary tract cancers, cholangiocarcinoma [6] | Superior mutation detection sensitivity compared to plasma [6] |

| Stool | Non-invasive; direct contact with colorectal mucosa [6] | Complex microbiome background | Colorectal cancer [6] | Excellent performance for early-stage colorectal cancer detection [6] |

Blood Collection and Initial Processing

Materials and Equipment

- Blood Collection Tubes: Cell-stabilizing tubes (e.g., Streck Cell-Free DNA BCT) or K2EDTA/K3EDTA tubes [29]

- Centrifuge: Capable of maintaining 4°C with swing-bucket rotor

- Pipettes: Sterile, single-use pipettes

- Cryovials: Sterile, nuclease-free tubes for plasma storage

- Personal Protective Equipment: Gloves, lab coat, eye protection

Step-by-Step Protocol

Blood Collection

- Venipuncture: Perform venipuncture using standard clinical procedures.

- Tube Filling: Draw blood into cell-stabilizing or EDTA tubes. Fill tubes to the recommended volume to maintain proper blood-to-additive ratio [29].

- Gentle Mixing: Invert tubes 8-10 times immediately after collection to ensure proper mixing with preservatives.

Plasma Separation

- Initial Centrifugation: Within 2 hours of collection (immediately if using EDTA tubes), centrifuge blood at 800-1600 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C [29]. This step separates plasma from cellular components.

- Plasma Transfer: Carefully transfer the upper plasma layer to a nuclease-free tube using a sterile pipette, avoiding disturbance of the buffy coat.

- Secondary Centrifugation: Centrifuge the transferred plasma at 16,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C to remove residual cellular debris [29].

- Aliquoting: Aliquot the cleared plasma into nuclease-free cryovials in volumes appropriate for downstream applications.

Storage

- Short-term: Store aliquots at -80°C if processing within 24 hours [29].

- Long-term: Maintain at -80°C; avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles.

cfDNA Extraction and Quantification

Materials and Equipment

- Commercial cfDNA Kits: QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit (Qiagen), Maxwell RSC ccfDNA Plasma Kit (Promega), or equivalent [29]

- Magnetic Stand: For magnetic bead-based extraction methods

- Spectrophotometer/Fluorometer: For DNA quantification (e.g., Qubit, Agilent Bioanalyzer, TapeStation)

- Heating Block or Thermal Cycler: For temperature-controlled incubations

- Elution Buffer: TE buffer or nuclease-free water

Step-by-Step Protocol

cfDNA Extraction

- Thawing: Thaw plasma aliquots at room temperature or 4°C.

- Protocol Selection: Follow manufacturer instructions for the selected commercial kit.

- Binding: Bind cfDNA to silica membranes or magnetic beads.

- Washing: Perform wash steps to remove contaminants (proteins, salts).

- Elution: Elute cfDNA in an appropriate volume (typically 20-50 μL) of elution buffer.

Quality Control and Quantification

- Concentration Measurement: Quantify cfDNA using fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit dsDNA HS Assay) for accurate measurement of low-concentration samples [30].

- Fragment Size Analysis: Assess fragment size distribution using microfluidic capillary electrophoresis (e.g., Agilent Bioanalyzer High Sensitivity DNA kit) [30]. Expect a peak at ~166 bp for mononucleosomal cfDNA.

- Purity Assessment: Measure A260/A280 ratio (ideal: 1.8-2.0) and A260/A230 ratio (ideal: >2.0) using spectrophotometry [30].

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Pre-Analytical Challenges

| Challenge | Potential Cause | Impact on Methylation Analysis | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low cfDNA Yield | Delayed processing; improper centrifugation; small plasma volume | Reduced sensitivity for detecting low-abundance methylation markers | Process samples within 2 hours; optimize centrifugation conditions; use adequate plasma volume (≥4 mL recommended) [29] |

| Genomic DNA Contamination | Cellular lysis during collection or processing; inadequate centrifugation | False positive methylation signals from hematopoietic cells | Use cell-stabilizing tubes; avoid rough handling; perform double centrifugation; check high-molecular-weight DNA contamination on Bioanalyzer [29] |

| cfDNA Degradation | Repeated freeze-thaw cycles; nuclease activity; improper storage | Incomplete bisulfite conversion; biased amplification | Limit freeze-thaw cycles; store at -80°C; use nuclease-free reagents [6] [29] |

| Hemolysis | Difficult blood draw; rough handling | Inhibition of downstream enzymatic steps; inaccurate quantification | Use proper phlebotomy technique; avoid drawing from hematomas; visually inspect plasma for pink/red discoloration |

DNA Methylation Analysis Workflow

The core analytical workflow for cfDNA methylation involves several critical steps, each requiring meticulous optimization to preserve the integrity of methylation information.

Diagram: Core cfDNA Methylation Analysis Workflow

DNA Treatment Methods

Bisulfite Conversion (Gold Standard)

- Principle: Converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils while methylated cytosines remain unchanged [29]

- Procedure:

- Denaturation: Incubate cfDNA in NaOH to create single-stranded DNA

- Sulfonation: Treat with sodium bisulfite (pH 5.0) at 50-60°C for 15-45 minutes [29]

- Desulfonation: Add NaOH to remove sulfonate groups

- Purification: Remove salts and reagents using column-based or bead-based cleanup

- Advantages: Single-base resolution; well-established protocols; comprehensive genome coverage [29]

- Limitations: DNA degradation (30-50% loss); inability to distinguish 5mC from 5hmC; over-conversion artifacts [29] [30]

Enzymatic Conversion (Emerging Alternative)

- Principle: Uses TET2 and APOBEC enzymes to protect and deaminate bases, respectively (e.g., EM-seq) [29]

- Procedure:

- Oxidation: Treat with TET2 to oxidize 5mC and 5hmC to 5caC

- Protection: Glycosylate 5hmC using oxidation enhancer

- Deamination: Apply APOBEC to deaminate cytosine but not protected bases

- Advantages: Minimal DNA degradation (<5%); distinguishes 5mC from 5hmC; compatible with low-input samples [29] [30]

- Limitations: Higher cost; newer methodology with less established protocols

Methylation Detection Platforms

Targeted Approaches

- Methylation-Specific PCR (qMSP): Quantitative method using primers specific to methylated sequences after bisulfite conversion [10]

- Digital PCR (ddPCR): Absolute quantification of methylated molecules; ideal for low-abundance targets [10]

- Multiplex ddPCR (mddPCR): Simultaneous detection of multiple methylation markers using different fluorescent probes [10]

Genome-Wide Approaches

- Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS): Comprehensive single-base resolution methylation profiling [6] [31]

- Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS): Cost-effective alternative focusing on CpG-rich regions [6]

- Methylation Arrays (Infinium): Medium-throughput profiling using beadchip technology (EPIC/850K array) [32] [30]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for cfDNA Methylation Analysis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood Collection Tubes | Streck Cell-Free DNA BCT, PAXgene Blood ccfDNA tubes | Preserve blood samples and prevent white blood cell lysis | Enable sample stability during transport; allow processing within up to 72 hours for BCT tubes [29] |

| cfDNA Extraction Kits | QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit, Maxwell RSC ccfDNA Plasma Kit | Isolate and purify cfDNA from plasma | Optimized for low-concentration, fragmented DNA; typically yield 60-80% recovery [29] |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits | EZ DNA Methylation kits (Zymo Research), EpiTect Fast DNA Bisulfite Kit (Qiagen) | Convert unmethylated cytosines to uracils | Include protection against DNA degradation; conversion efficiency >95% required [29] [30] |

| Enzymatic Conversion Kits | EM-Seq Kit (New England BioLabs) | Convert DNA using enzyme-based approach | Minimize DNA degradation (<5%); ideal for limited samples [29] [30] |

| Methylation-Specific PCR Reagents | Methylation-specific primers and probes, hot-start DNA polymerases | Amplify and detect methylated DNA sequences | Require optimization for bisulfite-converted templates; need validation to exclude false positives [10] |

| Library Preparation Kits | Accel-NGS Methyl-Seq DNA Library Kit (Swift Biosciences), KAPA HyperPrep Kit | Prepare sequencing libraries from bisulfite-converted DNA | Include uracil-tolerant polymerases; optimized for fragmented input DNA [6] |

| Quality Control Tools | Agilent Bioanalyzer High Sensitivity DNA kit, Qubit dsDNA HS Assay | Assess cfDNA quantity, quality, and fragment size | Essential for verifying sample integrity pre- and post-bisulfite conversion [30] |

Quality Control and Data Normalization

Robust quality control measures are essential throughout the cfDNA methylation workflow to ensure data reliability and reproducibility.

Diagram: Quality Control and Data Processing Workflow

Critical QC Metrics

- Bisulfite Conversion Efficiency: >99% using spike-in controls (e.g., Lambda DNA) [30]

- Sample Integrity: DNA integrity number (DIN) >7 for input DNA; fragment size distribution showing ~166 bp peak for cfDNA [30]

- Array-Based QC: Detection p-value <0.01 for all probes; consistent intensity across arrays [30]

- Sequencing-Based QC: >10M reads per sample for WGBS; bisulfite conversion rate >99% based on spike-ins [31]

Normalization Strategies

- Quantile Normalization: Standardizes signal distribution across samples [30]

- BMIQ Algorithm: Corrects for probe design biases in Infinium arrays [30]

- ComBat: Removes batch effects while preserving biological variation [30]

The reliability of cfDNA methylation biomarkers is fundamentally dependent on rigorous standardization of pre-analytical procedures. From appropriate biofluid selection through to methodical sample processing and DNA treatment, each step introduces potential variability that must be controlled through protocol optimization and comprehensive quality control. The methodologies detailed in this application note provide a framework for generating high-quality, reproducible cfDNA methylation data suitable for biomarker discovery and validation. As liquid biopsy applications continue to expand, adherence to these standardized pre-analytical practices will be essential for translating cfDNA methylation biomarkers from research settings into clinically actionable tools.

DNA methylation, the addition of a methyl group to cytosine at CpG dinucleotides, is a fundamental epigenetic mechanism regulating gene expression without altering the DNA sequence [33]. In cancer, DNA methylation patterns undergo significant alterations, often emerging early in tumorigenesis and remaining stable throughout tumor evolution [6]. These stable, cancer-specific methylation patterns in circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) make them exceptionally promising biomarkers for liquid biopsy applications, offering a minimally invasive approach for cancer detection, monitoring, and prognosis [6] [10].