Transgenerational Epigenetic Inheritance in Mammals: Evidence, Mechanisms, and Clinical Implications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance (TEI) in mammals for a scientific audience of researchers and drug development professionals.

Transgenerational Epigenetic Inheritance in Mammals: Evidence, Mechanisms, and Clinical Implications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance (TEI) in mammals for a scientific audience of researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational debate surrounding the evidence for TEI, contrasting it with the more established phenomenon in plants and invertebrates. The content delves into cutting-edge methodological approaches, including epigenome engineering, that demonstrate the potential for TEI and its application in disease modeling. A critical troubleshooting section addresses the major biological and technical confounders in TEI research, such as genetic inheritance and intrauterine exposure. Finally, the article examines the rigorous validation criteria and comparative biology needed to establish conclusive proof of TEI, synthesizing key takeaways for its potential impact on understanding disease etiology and developing novel therapeutic strategies.

Defining the Paradigm: Evidence and Debate for TEI in Mammals

Contrasting TEI in Mammals, Plants, and Invertebrates

Transgenerational Epigenetic Inheritance (TEI) describes the phenomenon where phenotypic traits induced by environmental factors are transferred to subsequent generations through epigenetic mechanisms rather than DNA sequence changes [1]. This field has revitalized the centuries-old debate about the inheritance of acquired characteristics, strongly contested since the Lamarckian and Darwinian eras [2]. While evidence for TEI is well-established in plants and invertebrates, its existence in mammals remains highly controversial due to fundamental biological differences in how organisms handle epigenetic information across generations [2] [3]. This technical guide examines the core mechanisms, experimental evidence, and methodological approaches for studying TEI across these taxonomic groups, with particular emphasis on the challenges specific to mammalian systems within the broader context of epigenetic research.

The central controversy in mammalian TEI stems from two waves of epigenetic reprogramming that occur during development: first in primordial germ cells and later in the developing embryo after fertilization [2]. These reprogramming events are characterized by global erasure of DNA methylation and remodeling of histone modifications, presenting a significant biological barrier to the transmission of epigenetic information [2]. Despite this barrier, some genomic regions—including imprinted control regions and transposable elements—resist complete reprogramming, creating potential windows for TEI to occur [2]. Understanding how these mechanisms differ across mammals, plants, and invertebrates is crucial for advancing research in environmental epigenetics, evolutionary biology, and toxicology.

Fundamental Biological Differences in TEI Mechanisms

Epigenetic Reprogramming Landscapes

The capacity for transgenerational epigenetic inheritance varies dramatically across taxonomic groups, primarily due to differences in epigenetic reprogramming events. The following table summarizes the key biological differences that influence TEI potential:

Table 1: Fundamental Biological Differences Affecting TEI Potential

| Characteristic | Mammals | Plants | Invertebrates (C. elegans) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Events | Two waves: in primordial germ cells and post-fertilization [2] | Limited reprogramming; no defined germline [3] | No extensive reprogramming comparable to mammals [2] |

| DNA Methylation Erasure | Global erasure with exceptions at imprinted regions & transposons [2] | Context-dependent maintenance; RNA-directed DNA methylation [3] | Minimal DNA methylation; alternative mechanisms [2] |

| Primary Epigenetic Carriers | DNA methylation (5mC), histone modifications [2] | DNA methylation, histone modifications, small RNAs [3] | Small RNAs (siRNAs, piRNAs), histone modifications [2] [3] |

| Germline Development | Early segregation; protected from somatic influences [2] | No preformation; germline differentiates late [3] | Preformed germline with enhanced permeability [3] |

| Evidence Strength | Controversial with rare examples (Agouti) [3] | Strong; numerous well-established examples [3] | Strong; RNAi-based mechanisms [2] [3] |

Key Epigenetic Mechanisms in TEI

The molecular mechanisms facilitating TEI differ significantly across biological kingdoms, with each taxonomic group employing distinct epigenetic carriers:

Mammals: DNA methylation represents the most extensively studied epigenetic marker in mammals. Despite global reprogramming, certain regions like imprinted control regions and transposable elements resist demethylation, potentially allowing environmental exposures to create heritable epigenetic marks [2]. Histone modifications (e.g., H3K9me3, H3K27me) may also contribute, though their heritability faces greater challenges due to histone exchange during reprogramming [2].

Plants: Unlike mammals, plants display robust TEI through multiple interconnected mechanisms including RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM), histone modifications, and small RNA pathways [3]. The absence of an early segregated germline allows somatic epigenetic states to be more readily transmitted to subsequent generations. Plants also lack the comprehensive epigenetic erasure that characterizes mammalian development [3].

Invertebrates: C. elegans and other invertebrates utilize small RNA pathways as primary carriers of epigenetic information. Environmental double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) triggers the RNA interference (RNAi) pathway, generating small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) that silence complementary genes across generations [2]. These secondary siRNAs propagate RNAi effects to subsequent generations, mediated by germline epigenetic modifications including PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) and specific histone modifications like H3K9me3 and H3K36 [2].

Experimental Evidence and Model Systems

Quantitative Evidence for TEI Across Taxa

Research across different model systems has produced varying levels of evidence for TEI, with quantitative data highlighting the strength of findings in different organisms:

Table 2: Key Experimental Models and Evidence for TEI

| Organism/Model | Environmental Exposure | Generations Affected | Key Phenotypic Outcomes | Epigenetic Changes Observed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agouti Mouse (Mammal) | Maternal methyl donor diet [2] | F1, F2 [2] | Coat color variation, obesity [2] | Increased methylation at 6 CpG sites in Avy retrotransposon [2] |

| Vinclozolin Rat (Mammal) | In utero fungicide exposure [2] | F1-F4 (claimed) [2] | Testicular abnormalities, infertility [2] | Altered DNA methylation patterns in sperm [2] |

| Dutch Famine Humans (Mammal) | Periconceptional malnutrition [2] | F1, F2 (neonatal adiposity) [2] | Metabolic disease, schizophrenia risk [2] | IGF2 hypomethylation (6 decades later) [2] |

| C. elegans (Invertebrate) | Pathogenic viruses/bacteria [3] | ≥ F3 [3] | Pathogen resistance [3] | siRNA-mediated silencing; H3K9me3 [2] |

| Arabidopsis (Plant) | Various abiotic stresses [3] | Multiple generations [3] | Flowering time, stress responses [3] | DNA methylation changes, histone modifications [3] |

Methodological Approaches for TEI Investigation

Mammalian TEI Research Protocols

Agouti Viable Yellow (Avy) Mouse Model Protocol

The Agouti mouse model represents one of the most robust mammalian systems for studying TEI. The following protocol outlines key methodological considerations:

Experimental Design:

- Expose pregnant female mice (F0 generation) to methyl donor-supplemented diet (e.g., extra folic acid, vitamin B12, choline) during specific gestational windows [2].

- Breed resulting offspring (F1) to unexposed partners to generate F2 generation, continuing to F3 without further exposure to establish transgenerational effects (F3 represents first truly transgenerational generation when considering maternal exposure) [2].

Phenotypic Assessment:

Molecular Analysis:

Critical Considerations: Sample size must be sufficient to detect modest effects, as early positive findings with small samples failed replication in larger studies [3]. The Agouti locus represents an exception rather than the rule in mammalian TEI, as screens for similar metastable epialleles have been largely negative [3].

Invertebrate TEI Research Protocols

C. elegans RNAi Inheritance Protocol

The C. elegans system provides a well-established model for studying RNA-based transgenerational inheritance:

Environmental Exposure:

Generational Tracking:

- Transfer exposed P0 animals to fresh plates without dsRNA or pathogen.

- Collect F1 embryos using standard bleaching protocols to ensure separation from parental environment.

- Continue tracking phenotypes through multiple generations (typically F3-F10) without further exposure [2].

Phenotypic Assessment:

- Monitor gene silencing through fluorescent reporters or phenotypic markers.

- For pathogen resistance assays, challenge offspring generations with pathogens and quantify survival rates [3].

Molecular Analysis:

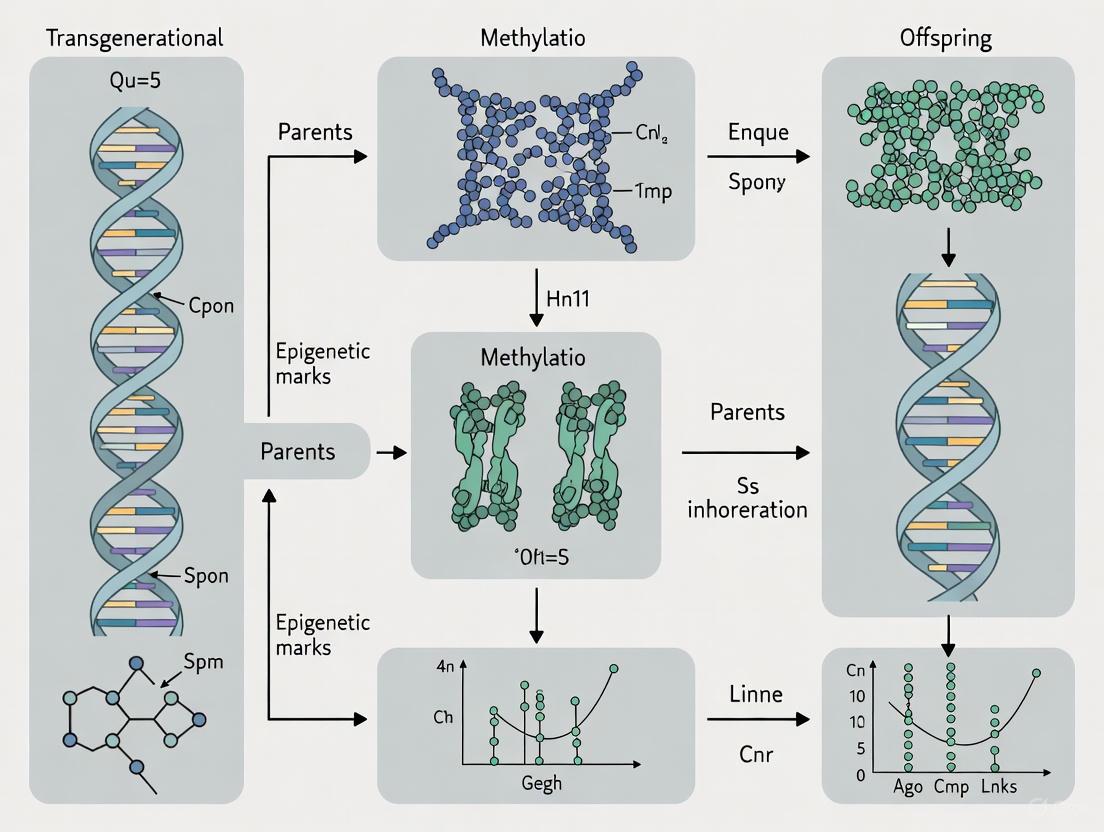

Visualizing Key Biological Pathways and Experimental Designs

Comparative Epigenetic Reprogramming Pathways

Mammalian TEI Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for TEI Investigation

| Reagent/Method | Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Bisulfite Conversion Reagents | Detection of DNA methylation patterns [2] | Distinguishes 5-methylcytosine from cytosine; optimized protocols needed for different species [2] |

| Methylation-Sensitive Restriction Enzymes | Methylation analysis at specific loci [2] | Requires careful controls for complete digestion; cost-effective for candidate regions [2] |

| Histone Modification Antibodies | Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) for histone marks [2] | Specificity validation critical; species compatibility important [2] |

| Small RNA Sequencing Kits | Analysis of siRNA, piRNA populations in TEI [2] | Specialized protocols for small RNA enrichment; essential for invertebrate and plant studies [2] |

| CRISPR/dCas9 Epigenetic Editors | Functional testing of specific epigenetic marks [3] | Enables targeted methylation/demethylation; distinguishes correlation from causation [3] |

| DNMT and TET Inhibitors | Manipulation of DNA methylation states [3] | Pharmacological modulation of methylation; specificity and toxicity concerns [3] |

| Methyl Donor Supplements | Dietary manipulation of methylation capacity (e.g., choline, folate) [2] | Used in Agouti mouse studies; timing critical for developmental windows [2] |

| Allobetulone | Allobetulone, CAS:28282-22-6, MF:C30H48O2, MW:440.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Combretastatin A4 | Combretastatin A4, CAS:117048-59-6, MF:C18H20O5, MW:316.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Critical Challenges and Methodological Considerations

Key Controversies in Mammalian TEI

The investigation of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance in mammals faces several fundamental challenges that contribute to the ongoing controversy in the field:

Biological Barriers: The two waves of epigenetic reprogramming in primordial germ cells and early embryos present a substantial biological hurdle for maintaining environmentally-induced epigenetic marks across generations [2]. As noted by researchers, "it is unlikely for environmentally induced or programmed epigenetic marks to be inherited" due to these reprogramming events [2].

Confounding Effects: Disentangling true germline epigenetic inheritance from other factors remains challenging. Potential confounders include intrauterine environmental effects, cytoplasmic factors, and the difficulty in distinguishing epigenetic changes from selection for genetic variants [2] [3]. Studies must carefully differentiate between intergenerational effects (direct exposure of gametes or fetus) versus true transgenerational inheritance (transmission through multiple generations without direct exposure) [2].

Reproducibility Issues: Several high-profile TEI findings have faced replication challenges. For example, while initial reports suggested diet could induce heritable changes in Agouti mice, subsequent studies with larger sample sizes failed to validate these findings [3]. Similarly, the transgenerational effects of vinclozolin exposure demonstrated in some rat strains were not reproducible in inbred mouse strains [2].

Evolutionary Considerations: The potential adaptive value of TEI remains debated. While some invertebrate and plant examples show clear adaptive benefits (e.g., pathogen resistance in C. elegans), most putative mammalian examples appear non-adaptive and resemble random epigenetic mutations rather than programmed responses [3]. As noted in recent research, "rather than eagerly harnessing environmental inputs from the life experiences of their ancestors via epigenetic mechanisms, organisms strive to prevent contamination of a new generation with the accumulated epigenetic baggage of the previous one" [3].

Methodological Recommendations for Robust TEI Research

To address these challenges, researchers should implement rigorous methodological approaches:

Generational Study Design: Properly design studies to distinguish intergenerational from transgenerational effects. In maternal exposure models, F3 represents the first transgenerational generation [2].

Multiple Strain Validation: Test findings across different genetic backgrounds to control for strain-specific effects, as demonstrated by the variable vinclozolin effects in outbred versus inbred mice [2].

Comprehensive Epigenomic Profiling: Move beyond candidate loci approaches to genome-wide epigenetic analyses while implementing appropriate multiple testing corrections [2].

Functional Validation: Utilize epigenetic editing tools (e.g., dCas9-effector fusions) to test the functional consequences of specific epigenetic changes rather than relying solely on correlative evidence [3].

The investigation of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance reveals profound differences across taxonomic groups, with robust mechanisms well-established in plants and invertebrates but remaining controversial in mammals. The contrasting biological strategies—from the extensive reprogramming barriers in mammals to the RNA-based inheritance pathways in invertebrates—highlight the diverse evolutionary solutions to balancing environmental responsiveness with genomic integrity across generations.

Future research directions should prioritize overcoming the methodological challenges that have plagued the field, particularly in mammalian systems. This includes developing more sensitive tools for detecting rare epigenetic variants that survive reprogramming, implementing rigorous multi-generational study designs, and applying epigenetic editing technologies to establish causal relationships. Furthermore, exploring the potential intersection between TEI and other inheritance mechanisms, including the transmission of microbial symbionts and parental effects, may provide a more comprehensive understanding of non-genetic inheritance.

For drug development professionals and translational researchers, the current evidence suggests caution in extrapolating TEI findings from invertebrate and plant models to mammalian systems. While the Agouti locus demonstrates that TEI can occur in mammals in specific circumstances, these appear to be exceptions rather than the rule. Nevertheless, understanding these mechanisms remains crucial for comprehensive toxicological risk assessment and for exploring potential long-term impacts of environmental exposures on human health across generations.

Epigenetics is the study of heritable and stable changes in gene expression that occur through alterations in the chromosome rather than in the DNA sequence [4]. These mechanisms form a crucial layer of control that regulates gene expression and silencing without changing the underlying genetic code, enabling cells with identical DNA sequences to develop into distinct cell types and respond to environmental cues [4]. The significance of epigenetic regulation extends beyond cellular differentiation to encompass potentially transgenerational effects, wherein environmentally induced modifications can be transmitted to subsequent generations.

In the context of mammalian transgenerational epigenetic inheritance (TEI), research focuses on how acquired traits can be transmitted through the germline without changes to the DNA sequence itself [5]. True transgenerational inheritance in mammals requires transmission that extends to at least the F2 generation after F0 paternal exposure, and to the F3 generation after F0 maternal exposure, thereby excluding direct exposure effects on the developing embryo or its germ cells [5]. This distinction is critical for establishing genuine epigenetic inheritance across generations, as opposed to intergenerational effects that result from direct exposure.

The three primary epigenetic mechanisms—DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNA-associated gene silencing—work in concert to regulate gene expression by modulating chromatin structure and accessibility [4]. These systems create a comprehensive network of regulatory pathways and feedback loops that can dynamically respond to environmental factors including age, diet, smoking, stress, and disease state [4] [6]. Understanding these core mechanisms provides the foundation for exploring how environmental experiences can potentially shape phenotypes across multiple generations, with profound implications for evolution, disease susceptibility, and therapeutic development.

DNA Methylation

Molecular Mechanisms and Enzymatic Regulation

DNA methylation represents a fundamental epigenetic mechanism involving the addition of a methyl group to cytosine nucleotides, predominantly within cytosine-guanine (CpG) dinucleotides [4]. This covalent modification is catalyzed by DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) enzymes, primarily DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B, which establish and maintain methylation patterns throughout the genome [6] [4]. DNMT1 functions as the maintenance methyltransferase, faithfully copying methylation patterns during DNA replication, while DNMT3A and DNMT3B serve as de novo methyltransferases that establish new methylation patterns during embryonic development [6].

The distribution of DNA methylation across the genome is non-random, with CpG islands—stretches of DNA with high CpG density—being particularly important regulatory targets. Approximately 70% of gene promoter regions lie within CpG islands, making them crucial elements for transcriptional regulation [4]. When methylated, these promoter-associated CpG islands recruit methyl-binding proteins and associated gene suppressor complexes that promote a compact chromatin state, effectively silencing gene expression by preventing transcription factors from accessing their target sequences [4] [5]. This repressive function positions DNA methylation as a key regulator of tissue-specific gene expression, genomic imprinting, and X-chromosome inactivation [4].

The dynamic nature of DNA methylation is maintained through active demethylation processes mediated by ten-eleven translocation (TET) enzymes, which oxidize 5-methylcytosine (5mC) to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) and further derivatives [5]. This oxidation pathway facilitates both passive and active DNA demethylation, allowing for erasure and reprogramming of epigenetic marks during specific developmental windows, particularly in primordial germ cells and early embryos [7] [5]. The balance between methylation and demethylation activities enables the epigenome to remain responsive to environmental signals while maintaining transcriptional stability.

Role in Transgenerational Inheritance and Evidence from Mammalian Studies

In the context of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance, DNA methylation represents the most extensively studied mechanism, though evidence for its role in mammals remains subject to ongoing scientific debate [7] [3]. The potential for methylation patterns to escape the widespread epigenetic reprogramming that occurs during early mammalian development is central to this discourse. This reprogramming involves genome-wide demethylation in primordial germ cells and subsequent remethylation around the time of embryo implantation, a process thought to be required for resetting genomic imprints and reactivating genes essential for proper development [7]. However, research indicates that this reset is not entirely complete, with specific genomic regions, particularly imprinted genes and transposable elements, demonstrating resistance to demethylation and thus potentially carrying epigenetic information across generations [7].

The Agouti viable yellow (Avy) mouse model provides one of the most compelling examples of metastable epialleles that exhibit transgenerational inheritance of DNA methylation patterns [3]. In this system, a transposable element inserted upstream of the Agouti gene exhibits variable methylation that correlates with coat color and disease susceptibility, and this methylation state shows modest but measurable heritability [3]. Early studies suggested that maternal diet, particularly methyl donor supplementation, could influence the epigenetic status of this locus in offspring, though subsequent larger studies have yielded conflicting results regarding the environmental responsiveness and transgenerational stability of these epigenetic marks [3].

Human studies have provided correlative evidence for transgenerational DNA methylation patterns, particularly in the context of early life stress and nutritional status [7]. For instance, analysis of individuals prenatally exposed to the Dutch Hunger Winter revealed persistent DNA methylation changes at specific loci, such as the imprinted IGF2 gene, decades after the initial exposure [4]. However, distinguishing true transgenerational inheritance from intergenerational effects in human studies presents significant methodological challenges, as it requires demonstrating transmission through multiple generations without continued direct exposure.

Table 1: DNA Methylation Patterns in Transgenerational Studies

| Study Model | Environmental Exposure | Methylation Changes | Generational Persistence | Associated Phenotypes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agouti Mice [3] | Maternal methyl donor diet | Avy locus hypomethylation | F1-F3 (with decreasing penetrance) | Yellow coat color, obesity, tumor susceptibility |

| Dutch Hunger Winter Cohort [4] | Prenatal famine | IGF2 hypomethylation | F1 only (intergenerational) | Metabolic disease, cardiovascular risk |

| Rat VOC Model [5] | Gestational toxicant exposure | Sperm DNA methylation changes | F1-F3 (transgenerational) | Testis disease, kidney disease, multiple disease states |

| Mouse High-Fat Diet [7] | Maternal high-fat diet | Neural stem cell methylation changes | F1-F3 (transgenerational) | Altered neurogenesis, metabolic changes |

Histone Modifications

The Histone Code Hypothesis and Major Modification Types

Histone modifications constitute a second major epigenetic mechanism that regulates gene expression by altering chromatin structure and DNA-histone interactions [4]. The "histone code" hypothesis proposes that covalent post-translational modifications to the N-terminal tails of histone proteins create a combinatorial language that determines chromosomal functional states [6]. These modifications occur primarily on the flexible histone tails that protrude from the nucleosome core and include acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and other chemical alterations [4].

Each modification type demonstrates specific functions in regulating chromatin dynamics and gene expression. Histone acetylation, catalyzed by histone acetyltransferases (HATs), involves the addition of acetyl groups to lysine residues, neutralizing their positive charge and consequently weakening DNA-histone interactions [4]. This charge neutralization promotes an open chromatin configuration (euchromatin) that facilitates transcription factor binding and gene activation [4]. Conversely, histone deacetylases (HDACs) remove acetyl groups, strengthening DNA-histone interactions and promoting transcriptional repression. Key activating acetylation marks include H3K9ac and H3K27ac, both associated with active transcription [4].

Histone methylation represents a more complex regulatory system that can either activate or repress transcription depending on the specific residue modified and its methylation state [4]. Unlike acetylation, methylation does not alter the charge of histone tails but instead creates binding platforms for chromatin-modifying complexes. For example, H3K4me3 is strongly associated with transcription activation, while H3K27me3 and H3K9me3 correlate with transcription repression and heterochromatin formation [4]. The functional outcome depends on the specific lysine or arginine residue modified, the degree of methylation (mono-, di-, or tri-methylation), and the broader chromatin context.

Table 2: Major Histone Modifications and Their Functional Consequences

| Modification Type | Histone Site | Enzymes Responsible | Chromatin State | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetylation | H3K9, H3K14, H3K27, H4K16 | HATs, HDACs | Open euchromatin | Transcriptional activation |

| Methylation (activating) | H3K4, H3K36, H3K79 | HMTs, KDMs | Open euchromatin | Transcriptional activation |

| Methylation (repressive) | H3K9, H3K27, H4K20 | HMTs, KDMs | Closed heterochromatin | Transcriptional repression |

| Phosphorylation | H3S10 | Kinases, phosphatases | Condensed chromatin | Mitosis, DNA damage response |

| Ubiquitination | H2AK119, H2BK123 | E3 ubiquitin ligases | Variable | Transcriptional regulation, DNA repair |

Experimental Methodologies for Histone Modification Analysis

The investigation of histone modifications employs a diverse array of molecular techniques that enable researchers to map modification patterns, quantify abundance, and determine functional consequences. Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) represents the gold standard for genome-wide mapping of histone modifications [6]. This methodology involves cross-linking proteins to DNA, chromatin fragmentation, immunoprecipitation with modification-specific antibodies, and high-throughput sequencing of associated DNA fragments. The resulting data provides comprehensive maps of histone modification distributions across the genome, enabling correlation with gene expression states and identification of regulatory elements.

Mass spectrometry-based approaches offer complementary quantitative information about histone modification states, allowing for precise measurement of modification abundances and combinatorial patterns without antibody-based biases [6]. These techniques typically involve histone extraction, chemical derivatization, protease digestion, and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis. The resulting data provides quantitative information about the relative abundance of specific modifications and can reveal crosstalk between different modification types.

For functional validation, CRISPR/Cas9-based epigenetic editing systems enable targeted manipulation of histone modifications at specific genomic loci [7]. These approaches fuse catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) with histone-modifying domains to recruit specific enzymatic activities to defined genomic locations. For example, dCas9-p300 promotes histone acetylation and gene activation, while dCas9-LSD1 facilitates demethylation and gene repression. These tools allow researchers to establish causal relationships between specific histone modifications and transcriptional outcomes, moving beyond correlation to demonstrate functional significance.

Evidence for Transgenerational Transmission of Histone Modifications

While DNA methylation has traditionally been the focus of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance research, emerging evidence suggests that histone modifications may also contribute to epigenetic transmission across generations, particularly in mammalian systems [5]. This represents a significant conceptual challenge, as the majority of histones are replaced by protamines during spermatogenesis and extensively remodeled following fertilization. However, recent studies have identified a small but significant percentage of nucleosomes that are retained in sperm and may carry paternal epigenetic information [5].

Research in C. elegans has demonstrated that certain histone modifications, particularly H3K4me and H3K9me, can be transmitted across multiple generations and influence gene expression in progeny [3]. However, these effects are often dependent on mutant backgrounds that lack the histone modification erasure machinery present in wildtype organisms, suggesting that efficient removal mechanisms typically prevent transgenerational perpetuation of most histone marks [3]. Similarly, studies in S. pombe have shown that heterochromatic histone modifications can be maintained across generations but require specific environmental conditions or genetic backgrounds to escape resetting mechanisms.

In mammals, the evidence for transgenerational inheritance of histone modifications remains limited and controversial. Some studies have reported transmission of histone methylation patterns, such as H3K4me3 and H3K27me3, at specific developmental gene loci [5]. For example, paternal exposure to stress or toxicants has been associated with altered H3K4 methylation in sperm and corresponding behavioral and metabolic phenotypes in offspring [5]. However, these findings are complicated by the extensive epigenetic reprogramming that occurs during early mammalian development and the technical challenges of distinguishing true epigenetic inheritance from other forms of transmission.

Non-Coding RNAs

Classification and Functional Mechanisms

Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) represent a diverse class of functional RNA molecules that are transcribed from DNA but not translated into proteins, playing crucial roles in epigenetic regulation and gene silencing [4]. Once considered genomic "junk," ncRNAs are now recognized as essential components of the epigenetic machinery, potentially accounting for significant phenotypic variation despite similarity in protein-coding sequences [4]. The ncRNA family encompasses multiple classes distinguished by size, structure, biogenesis, and functional mechanisms.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) constitute the most extensively studied class of small ncRNAs, comprising evolutionary conserved transcripts of 17-25 nucleotides that regulate gene expression at the post-transcriptional level [6]. miRNA biogenesis involves sequential processing of primary miRNA transcripts by Drosha and Dicer enzymes, resulting in mature miRNAs that guide the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) to complementary target mRNAs. Perfect complementarity leads to mRNA cleavage and degradation, while partial complementarity, more common in mammals, results in translational repression [6]. The specificity of miRNA targeting is determined primarily by nucleotides 2-7 from the 5' end, known as the "seed sequence," which must base-pair with the 3' untranslated region of target mRNAs [6].

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) represent a more heterogeneous class defined as transcripts exceeding 200 nucleotides with limited protein-coding potential [6]. These molecules exhibit lower evolutionary conservation than miRNAs and frequently display cell- and tissue-specific expression patterns [6]. lncRNAs function through diverse mechanisms, acting as scaffolds, guides, decoys, or signals in complex regulatory networks [6]. As molecular scaffolds, they assemble multi-protein complexes that coordinate biological processes; as guides, they direct chromatin-modifying enzymes to specific genomic loci; as decoys, they sequester transcription factors or miRNAs; and as signals, they mark specific developmental stages or chromosomal territories [6].

Additional ncRNA classes include small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), which share biogenesis and effector mechanisms with miRNAs but derive from different precursor molecules, and piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs), which are 26-31 nucleotides in length and associate with Piwi proteins to silence transposable elements in the germline [6]. Circular RNAs (circRNAs), produced through noncanonical back-splicing events, have emerged as important regulators that can function as miRNA sponges, protein decoys, or templates for translation [6].

Methodologies for ncRNA Analysis and Functional Characterization

The study of ncRNAs employs specialized methodologies tailored to their unique properties and functions. For miRNA profiling, quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) arrays and small RNA sequencing represent the most common approaches for expression analysis [6]. These techniques enable comprehensive characterization of miRNA abundance across different tissues, developmental stages, or experimental conditions. Functional investigation typically involves miRNA inhibition using antisense oligonucleotides (antagomirs) or mimics for overexpression, followed by assessment of phenotypic consequences and target validation.

For lncRNA analysis, RNA sequencing provides the most powerful approach for discovery and expression profiling, while RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (RNA-FISH) enables spatial localization within cells and tissues [6]. Functional characterization often employs antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) or RNA interference for knockdown, complemented by CRISPR-based approaches for genomic deletion. To identify lncRNA interaction partners, techniques such as RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) and cross-linking immunoprecipitation (CLIP) determine protein binding partners, while chromatin isolation by RNA purification (ChIRP) maps genomic association sites [6].

High-throughput screening approaches have been developed to systematically interrogate ncRNA function, including pooled CRISPR screens targeting lncRNA loci and combinatorial miRNA inhibitor libraries. These unbiased approaches facilitate discovery of functionally significant ncRNAs within specific biological contexts, providing insights into their roles in development, homeostasis, and disease processes.

Role in Transgenerational Epigenetic Inheritance

Non-coding RNAs have emerged as compelling candidates for mediators of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance, particularly in the context of environmentally induced phenotypes [7] [5]. The germline enrichment of specific ncRNA classes, their ability to shuttle between tissues, and their capacity to instruct epigenetic modifications position them as potential vectors for transmitting environmental information across generations.

In invertebrate models, compelling evidence demonstrates RNA-based transgenerational inheritance. In Caenorhabditis elegans, exposure to viral RNA triggers the production of small interfering RNAs that are transmitted to subsequent generations, conferring pathogen resistance in the absence of continued exposure [3]. Similarly, starvation-induced changes in small RNA profiles can be inherited for multiple generations, associated with corresponding alterations in gene expression and lifespan [5]. These RNA-based inheritance mechanisms represent evolved adaptive responses that provide progeny with pre-existing resistance to environmental challenges encountered by their ancestors.

Mammalian studies have provided more limited but suggestive evidence for ncRNA-mediated transgenerational inheritance. Paternal exposure to stress, toxins, or dietary manipulation has been associated with changes in sperm small RNA profiles, including miRNAs, tsRNAs, and piRNAs [5]. For instance, paternal trauma exposure alters sperm miRNA content, with corresponding behavioral and metabolic phenotypes in offspring [5]. Similarly, paternal obesity modifies sperm tsRNA profiles, and injection of these tsRNAs into normal zygotes recapitulates metabolic dysfunction in the resulting offspring [5]. These findings suggest that sperm-borne RNAs can carry paternal environmental information to the next generation.

The mechanistic basis for RNA-mediated inheritance likely involves regulation of early embryonic development, during which sperm-delivered RNAs may influence epigenetic reprogramming and gene expression patterns [5]. However, significant questions remain regarding the stability of RNA molecules across generations, the specificity of their effects, and the relative contribution of RNA-mediated mechanisms compared to other epigenetic pathways. Additionally, the potential for non-germline transmission through behavioral or cultural means complicates the interpretation of transgenerational phenomena in mammals.

Experimental Approaches for Studying Transgenerational Epigenetic Inheritance

Model Systems and Methodological Considerations

The investigation of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance requires carefully controlled experimental designs that account for species-specific biological considerations and distinguish true germline transmission from other forms of inheritance [5]. In mammalian systems, proper experimental design must account for the distinction between intergenerational and transgenerational effects [5]. For maternal exposures, transmission to the F3 generation represents the first transgenerational cohort, as the F2 generation germline was directly exposed in the developing F1 fetus [5]. For paternal exposures, the F2 generation is considered transgenerational, as only the F1 generation germline was directly exposed [5].

Invertebrate models, including C. elegans and D. melanogaster, offer significant advantages for TEI research due to their short generation times, well-characterized genetics, and simplified germline development [5]. These systems enable large-scale screening approaches and precise manipulation of epigenetic pathways. Plant models, particularly Arabidopsis thaliana, have also provided fundamental insights into TEI mechanisms, with well-documented examples of stress-induced epigenetic changes that persist across generations [7].

Mammalian studies predominantly utilize rodent models, with exposures typically administered during specific developmental windows to target germline epigenetic programming [7] [5]. Common exposure paradigms include gestational nutrient manipulation, toxin administration, stress protocols, and endocrine disruptor exposure. Subsequent generations are maintained without additional exposure to assess transgenerational transmission of epigenetic marks and associated phenotypes.

Molecular Assessment Techniques

Comprehensive assessment of TEI requires multi-level molecular profiling across generations. DNA methylation analysis typically employs whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) for comprehensive mapping or reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) for cost-effective profiling of CpG-rich regions [7]. These approaches enable identification of differentially methylated regions (DMRs) that persist across generations and correlate with phenotypic outcomes.

Histone modification analysis primarily utilizes ChIP-seq with modification-specific antibodies, though this approach is limited by antibody quality and availability [6]. Mass spectrometry-based methods provide complementary quantitative data but require specialized instrumentation and expertise [6].

Non-coding RNA profiling employs small RNA sequencing for comprehensive characterization, with particular focus on sperm RNA content in paternal transmission studies [5]. Integration of multiple datasets through multi-omics approaches provides the most powerful strategy for identifying conserved epigenetic signatures of transgenerational inheritance.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Methodologies for TEI Research

| Research Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epigenome Editing Systems | dCas9-DNMT3A, dCas9-TET1, dCas9-p300, dCas9-LSD1 | Targeted epigenetic manipulation; causal validation | Potential for off-target genetic effects [7] |

| DNA Methylation Profiling | WGBS, RRBS, Illumina EPIC Array | Genome-wide methylation mapping; DMR identification | Bisulfite conversion efficiency; coverage depth |

| Histone Modification Analysis | ChIP-seq, CUT&RUN, mass spectrometry | Histone mark mapping; quantitative modification analysis | Antibody specificity; chromatin shearing optimization |

| Non-coding RNA Profiling | Small RNA-seq, miRNA arrays, single-cell RNA-seq | ncRNA expression quantification; biomarker discovery | RNA integrity; normalization strategies |

| Animal Models | C. elegans, Drosophila, mouse, rat | TEI pathway discovery; exposure effect characterization | Species-specific epigenetic reprogramming patterns |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table summarizes key research reagents and materials essential for investigating epigenetic mechanisms and transgenerational inheritance, compiled from current methodologies described in the scientific literature.

Table 4: The Scientist's Toolkit for Epigenetic Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifics |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Methyltransferase Inhibitors | Demethylating agents; cancer therapy | Azacytidine, Decitabine (FDA-approved) [4] |

| Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors | Increase histone acetylation; cancer therapy | Panobinostat, Romidepsin (FDA-approved) [4] |

| CRISPR-dCas9 Epigenetic Editors | Targeted epigenetic modification | dCas9-DNMT3A (methylation), dCas9-p300 (acetylation) [7] |

| Modification-Specific Antibodies | Histone mark detection; ChIP experiments | H3K4me3 (active), H3K27me3 (repressive) [6] [4] |

| Bisulfite Conversion Reagents | DNA methylation mapping | Sodium bisulfite for cytosine conversion [7] |

| Small RNA Inhibitors | Functional ncRNA characterization | Antagomirs, ASOs for miRNA inhibition [6] |

| Transgenerational Animal Models | TEI pathway discovery | Agouti mice, C. elegans RNAi models [5] [3] |

| Protriptyline Hydrochloride | Protriptyline Hydrochloride, CAS:1225-55-4, MF:C19H22ClN, MW:299.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Cefoselis | Cefoselis, CAS:122841-10-5, MF:C19H22N8O6S2, MW:522.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate key signaling pathways and experimental workflows in epigenetic research, created using Graphviz DOT language with adherence to the specified color palette and contrast requirements.

Diagram 1: Epigenetic Regulation of Gene Expression

Diagram 2: Transgenerational Inheritance Experimental Design

The field of epigenetics has revolutionized our understanding of gene regulation and inheritance, revealing sophisticated mechanisms that interface with environmental signals to shape phenotypes within and potentially across generations. The core epigenetic mechanisms—DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNAs—function not in isolation but as integrated components of a comprehensive regulatory network that controls chromatin structure and gene expression [6]. While evidence for transgenerational epigenetic inheritance is well-established in plants and invertebrate animals, its significance in mammals remains a subject of ongoing investigation and debate [7] [3].

The clinical implications of epigenetic research are substantial, particularly in cancer biology, where epigenetic dysregulation represents a hallmark of carcinogenesis [4]. The FDA approval of epigenetic therapies such as azacytidine, decitabine, panobinostat, and romidepsin demonstrates the translational potential of targeting epigenetic mechanisms [4]. Furthermore, the reversible nature of epigenetic modifications offers promising therapeutic avenues for diverse conditions, including neurological disorders, metabolic diseases, and imprinting disorders [4].

Future research directions will likely focus on developing more precise epigenetic editing tools, resolving the functional relationships between different epigenetic layers, and elucidating the mechanisms that allow specific epigenetic marks to escape reprogramming during mammalian development [7] [5]. The potential contribution of epigenetic mechanisms to evolutionary processes also represents an exciting frontier, particularly regarding how environmental experiences might shape phenotypic variation and adaptation across generations [7]. As technologies for epigenome mapping and manipulation continue to advance, so too will our understanding of these fundamental regulatory processes and their roles in health, disease, and inheritance.

In mammalian development, the germline serves as a timeless bridge between generations, necessitating the resetting of epigenetic information to restore totipotency. Primordial germ cells (PGCs) undergo genome-wide epigenetic reprogramming, a process characterized by the extensive erasure of DNA methylation to establish a basal epigenetic state. However, this reprogramming is incomplete. Specific genomic regions, including those associated with evolutionarily young retrotransposons and certain metabolic and neurological disorder genes, demonstrate resistance to demethylation. This selective retention of epigenetic marks creates a "reprogramming barrier," forming a potential molecular substrate for transgenerational epigenetic inheritance. This whitepaper delves into the technical nuances of this barrier, detailing the mechanisms of erasure and retention, their implications for disease and evolution, and the advanced methodologies illuminating this critical biological process.

The germline is the custodian of genetic and epigenetic information that must be passed to the next generation. To ensure each offspring starts life without the accumulated epigenetic modifications of their parents, mammalian PGCs undergo a dramatic epigenetic reprogramming event [8]. This process involves the genome-wide erasure of DNA methylation, which resets genomic potential and is crucial for the acquisition of totipotency—the ability of a cell to give rise to any cell type of an organism [8] [9]. A pivotal feature of this reprogramming is the near-complete elimination of DNA methylation, with global levels dropping to less than 5% in human PGCs (hPGCs) by weeks 5-7 of development [9]. This demethylation encompasses the erasure of parental genomic imprints and facilitates X chromosome reactivation [8] [9].

Despite the global trend toward hypomethylation, certain genomic sequences resist this reprogramming, creating a barrier to complete erasure. These resistant loci provide a potential mechanism for the transmission of epigenetic information across generations, independent of DNA sequence changes—a phenomenon termed transgenerational epigenetic inheritance [7] [9]. The evidence for this in mammals remains a subject of intense debate and research, as distinguishing true transgenerational inheritance from intergenerational effects requires rigorous criteria [7] [10]. This whitepaper explores the mechanisms underlying this great reprogramming barrier, framing it within the context of its potential impact on mammalian biology and human disease.

Mechanisms of Epigenetic Erasure

Epigenetic reprogramming in PGCs is a coordinated process involving dynamic changes in both DNA methylation and histone modifications.

DNA Demethylation: Active and Passive Pathways

The erasure of DNA methylation in PGCs is driven by a combination of passive and active mechanisms.

- Passive Demethylation: This replication-dependent process occurs through the repression of key components of the DNA methylation machinery. In hPGCs, expression of the de novo DNA methyltransferases DNMT3A and DNMT3B and the maintenance methyltransferase cofactor UHRF1 is suppressed. Without these factors, DNA methylation is not maintained after successive cell divisions, leading to its gradual dilution [8].

- Active Demethylation: This replication-independent process is facilitated by the Ten-Eleven Translocation (TET) family of enzymes (TET1, TET2, TET3). These enzymes oxidize 5-methylcytosine (5mC) to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) and further to 5-formylcytosine (5fC) and 5-carboxycytosine (5caC). These oxidized derivatives can then be excised by thymine-DNA glycosylase (TDG) and replaced with an unmodified cytosine through base excision repair [8]. The expression of TET1 and TET2 is enriched in hPGCs, driving this active demethylation pathway [8].

Table 1: Key Enzymes and Factors in PGC DNA Methylation Erasure

| Factor | Role in DNA Methylation | Activity/Expression in PGCs | Effect on Methylation |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNMT3A/B | De novo methylation | Repressed [8] | Promotes passive demethylation |

| UHRF1 | Targets DNMT1 to hemi-methylated sites | Repressed [8] | Promotes passive demethylation |

| TET1/2 | Oxidizes 5mC to 5hmC, 5fC, 5caC | Enriched [8] | Drives active demethylation |

| TDG | Excises 5fC and 5caC | Implicated in active pathway [8] | Completes active demethylation cycle |

Histone Modification and Chromatin Reorganization

Concurrent with DNA demethylation, the chromatin landscape of PGCs is extensively reorganized. Histone modifications serve a critical regulatory function, particularly in compensating for the loss of DNA methylation-based transcriptional control [8]. Key changes include:

- Repressive Mark Dynamics: The repressive mark H3K9me2 is present at lower levels in PGCs compared to surrounding somatic cells. In contrast, H3K27me3 shows a more complex pattern, being stronger in migratory PGCs but becoming depleted by weeks 7-9 in humans. H3K27me3 is involved in chromatin compaction and may act as a temporary repressive mechanism during reprogramming [8].

- Chromatin State: The global changes in histone modifications contribute to a more open chromatin configuration, facilitating the large-scale transcriptional changes required for PGC development and the resetting of pluripotency.

The Reprogramming Barrier: Loci Resisting Erasure

The paradigm of global epigenetic erasure is challenged by the discovery of specific genomic sequences that demonstrate resilience to demethylation. These resistant loci constitute the "reprogramming barrier."

Classes of Resistant Sequences

Research has identified several categories of sequences that consistently retain DNA methylation in hPGCs despite the global hypomethylated state [9]:

- Evolutionarily Young Retrotransposons: Notably, SVA (SINE-VNTR-Alu) elements, which are primate-specific retrotransposons, show significant resistance to demethylation. These elements are considered potentially "hazardous" due to their ability to mobilize and cause genomic instability, suggesting that their sustained silencing is a protective genome-defense mechanism [9].

- Germline Gene-Associated Loci: Intriguingly, some resistant regions are single-copy sequences located near genes critical for germline development. The persistent methylation at these sites may fine-tune the transcriptional program of the germline [9].

- Metabolic and Neurological Disorder Loci: A finding with profound implications for human disease is that some loci associated with metabolic and neurological disorders resist demethylation. This identifies them as candidate regions for mediating epigenetic memory and transgenerational inheritance of disease susceptibility in humans [9].

Mechanisms Protecting Against Demethylation

The molecular basis for this resistance is an area of active investigation. The prevailing hypothesis is that these regions are protected by specific protein factors or local chromatin environments that either shield them from the demethylation machinery or actively promote maintenance methylation. The resistance is not absolute; rather, these regions exhibit slower demethylation kinetics compared to the rest of the genome, suggesting a nuanced and regulated process [8].

Technical and Experimental Approaches

Studying the ephemeral population of human PGCs presents significant technical challenges. Advances in technology and in vitro modeling have been instrumental in driving progress.

Key Methodologies for Profiling Epigenetic States

- Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (BS-seq): This is the gold-standard method for assessing DNA methylation at single-base resolution. Treatment of DNA with sodium bisulfite converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils (read as thymines in sequencing), while methylated cytosines remain unchanged. Applying this to purified hPGCs allows for the base-resolution mapping of the methylome during reprogramming [9]. A key limitation is that it cannot distinguish between 5mC and 5hmC.

- RNA-Sequencing (RNA-seq): This technique provides a comprehensive quantitative profile of the transcriptome. It has been critical for defining the unique gene regulatory network of hPGCs, which differs from that of mouse PGCs, and for tracking the expression of reprogramming factors like TET enzymes and DNMTs [8] [9].

- Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS): The isolation of pure populations of hPGCs from human embryonic tissues is paramount. A high-purity FACS protocol using cell-surface markers TNAP (tissue non-specific alkaline phosphatase) and c-KIT has been established, enabling the isolation of hPGC populations with >97% purity for downstream molecular analyses [9].

AnIn VitroModel: Human PGC-Like Cells (hPGCLCs)

Given the ethical and practical constraints of studying early human development, researchers have developed in vitro models. By differentiating human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) into human PGC-like cells (hPGCLCs), it is possible to recapitulate key aspects of PGC specification and epigenetic reprogramming [8] [9]. This model system allows for genetic manipulation and high-throughput screening that would be impossible in vivo.

Visualization of Key Concepts

Diagram 1: Epigenetic Reprogramming and Resistance in Human Primordial Germ Cells

Diagram 2: Molecular Pathways of DNA Methylation Erasure

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Germline Reprogramming Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| FACS Antibodies | Isolation of pure PGC populations | Anti-TNAP and anti-c-KIT for high-purity hPGC sorting [9] |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kit | Preparing DNA for methylation sequencing | Critical for BS-seq; distinguishes methylated vs. unmethylated C [8] [9] |

| hESC Lines | In vitro model for PGC development | Used to differentiate into hPGCLCs [8] [9] |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | Gene editing for functional studies | Used to interrogate the role of specific genes (e.g., TETs, DNMTs) [7] |

| Anti-5mC/5hmC Antibodies | Immunostaining for methylation/hydroxymethylation | Visualizing global epigenetic states in cells/tissues |

| RNA-seq Library Prep Kits | Transcriptome profiling | Analyzing gene expression networks in PGCs vs. soma [9] |

Implications for Transgenerational Epigenetic Inheritance and Disease

The incomplete erasure of epigenetic marks in the germline provides a plausible molecular substrate for transgenerational epigenetic inheritance in mammals.

The Debate and Evidence

The field is marked by ongoing debate regarding the robustness of evidence in mammals. A critical review of 80 articles found that many claims did not meet the necessary criteria, which include: inheritance of the same epimutations across generations, associated gene expression changes, and confirmation of the epimutation in the germ cells of each generation [7]. However, other studies provide compelling data. For instance, exposure of gestating rats to plastic-derived compounds led to specific DNA methylation biomarkers in the sperm of the F3 generation, which were linked to diseases like testis and kidney pathologies [7]. Similarly, a high-fat diet in F0 female mice induced epigenetic changes in neural stem cells that persisted into the F3 generation, despite subsequent generations consuming a standard diet [7].

Linking Resistant Loci to Human Disease

The discovery that loci associated with metabolic and neurological disorders are among those resistant to demethylation in hPGCs directly links the reprogramming barrier to human health [9]. This suggests that environmental exposures could potentially lead to epigenetic alterations in these resistant loci, which, if not fully erased in the germline, could be transmitted to offspring, influencing their disease susceptibility. This mechanism could contribute to the heritability of complex disorders like type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity [7].

The journey of primordial germ cells through epigenetic reprogramming is one of profound renewal, yet it is punctuated by deliberate retention. The "Great Reprogramming Barrier" is not a failure of the reset mechanism but appears to be a regulated, functional feature of germline development. It serves to protect genome integrity by silencing hazardous repetitive elements while simultaneously creating a potential archive of epigenetic information that may influence the phenotype of subsequent generations. The resistance of specific disease-associated loci to demethylation underscores the profound implications of this biology for human health. Future research, leveraging increasingly sophisticated in vitro models and single-cell multi-omics technologies, will be essential to fully decipher the mechanisms governing this barrier and to unequivocally determine its role in transgenerational epigenetic inheritance in mammals.

Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance (TEI) represents a paradigm shift in our understanding of heritability, demonstrating that acquired phenotypic traits can be transmitted to subsequent generations without alterations to the primary DNA sequence [5]. This phenomenon challenges strictly Mendelian views of inheritance and suggests that environmental factors experienced by ancestors can shape the biology and health of their descendants through epigenetic mechanisms. In mammals, definitive evidence for TEI requires transmission beyond the first unexposed generation: to the F2 generation for paternal exposure, and to the F3 generation for maternal exposure, thereby excluding direct exposure effects on the germline or developing embryo [5] [2]. This whitepaper examines key historical and contemporary case studies that have shaped our understanding of TEI, focusing on the seminal Agouti mouse model and extending to more recent mammalian studies, with particular emphasis on their implications for biomedical research and therapeutic development.

The molecular executors of epigenetic information include DNA methylation, histone modifications, non-coding RNAs, and chromatin remodeling complexes [5]. While these mechanisms are well-established in regulating gene expression within an organism's lifetime, their persistence through the extensive epigenetic reprogramming events that occur during mammalian gametogenesis and embryogenesis presents a fundamental biological puzzle [11] [2]. Despite these reprogramming barriers, a growing body of evidence from multiple mammalian species indicates that certain epigenetic marks can escape erasure and influence phenotypes across generations.

The Agouti Viable Yellow (Avy) Mouse: A Foundational Model

Historical Context and Molecular Basis

The Agouti viable yellow (Avy) mouse model stands as one of the most extensively studied and historically significant examples of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance in mammals. This model originated decades ago with the discovery of a mouse exhibiting an unexpected yellow coat in a C3H/HeJ colony [12]. Molecular characterization revealed that the Avy allele resulted from the insertion of an intracisternal A particle (IAP), a murine retrotransposon, upstream of the transcription start site of the Agouti gene [13]. The wild-type Agouti gene encodes a paracrine signaling molecule that regulates melanin production, typically resulting in a brown ("agouti") coat color with a sub-apical yellow band on each hair shaft [13].

The critical mechanistic feature of the Avy allele is a cryptic promoter within the proximal end of the Avy IAP that drives constitutive, ectopic expression of the Agouti gene [13]. This ectopic expression not only affects coat color but also leads to pleiotropic effects including adult-onset obesity, diabetes, and increased tumor susceptibility [14]. The activity of this cryptic promoter is inversely correlated with the DNA methylation status of CpG sites within the IAP's long terminal repeat (LTR); hypomethylation permits Agouti expression (yellow coat), while hypermethylation silences the locus (pseudoagouti coat) [13] [15].

Epigenetic Inheritance and Environmental Modulation

The Avy locus is classified as a "metastable epiallele" – identical DNA sequences that can be variably expressed in a stable manner due to epigenetic modifications established early in development [13]. Isogenic Avy/a mice display a remarkable range of coat colors, from fully yellow through mottled to fully pseudoagouti (brown), reflecting their individual epigenetic mosaicism at this locus [14] [15].

Table 1: Environmental Influences on the Avy Epigenome

| Environmental Factor | Effect on Avy Methylation | Phenotypic Outcome | Generational Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal Genistein Supplementation (Soy Phytoestrogen) | Increased methylation at 6 CpG sites within Avy IAP | Shift toward pseudoagouti coat color; protection from obesity | Persistent into adulthood (F1) [13] |

| Maternal Bisphenol A (BPA) Exposure | Decreased methylation at 9 CpG sites within Avy IAP | Shift toward yellow coat color | Fetal (F1) [13] |

| Maternal Methyl Donor Supplementation (Folic Acid, Betaine, Vitamin B12, Choline) | Counteracted BPA-induced hypomethylation | Protection from BPA-induced yellow shift | Fetal (F1) [13] |

| Maternal Genistein + Methyl Donors | Abolished BPA-induced hypomethylation | Protection from BPA-induced phenotypic changes | Fetal (F1) [13] |

The inheritance patterns at the Avy locus demonstrate clear non-Mendelian characteristics. The epigenetic state shows maternal transmission bias, with pseudoagouti mothers producing a higher proportion of pseudoagouti offspring, regardless of the sire's phenotype [14]. This inheritance occurs despite the extensive epigenetic reprogramming that takes place during mammalian development, suggesting that the epigenetic mark at this locus is incompletely erased in the female germline [14].

Research using the Avy model has been instrumental in demonstrating that nutritional and environmental exposures during critical developmental windows can permanently alter the epigenetic establishment and inheritance. Maternal dietary supplementation with the soy phytoestrogen genistein increases DNA methylation at the Avy IAP, shifting offspring coat color toward pseudoagouti and providing protection against obesity [13]. Conversely, maternal exposure to the endocrine disruptor bisphenol A (BPA) induces hypomethylation at the Avy locus, shifting coat color toward yellow [13]. Importantly, these BPA-induced effects can be counteracted by maternal nutritional supplementation with methyl donors or genistein, demonstrating the potential for dietary interventions to mitigate environmental toxicant effects [13].

Methodological Approaches

Key experimental methodologies employed in Avy mouse research include:

Southern Blot Analysis of DNA Methylation: This traditional approach utilizes methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes (e.g., HpaII) and probes specific to the Avy IAP region to assess methylation status. DNA is digested with BamHI plus either HpaII (methylation-sensitive) or its isoschizomer MspI (methylation-insensitive), followed by Southern transfer and hybridization with an Agouti-specific probe. Methylation levels are quantified by the ratio of uncut to cut fragments [15].

Bisulfite Sequencing: This gold-standard method provides single-base resolution DNA methylation data. Genomic DNA is treated with sodium bisulfite, which converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils (read as thymines in sequencing), while methylated cytosines remain unchanged. The target region is then PCR-amplified and sequenced, allowing precise mapping of methylated CpG sites [15].

Phenotypic Scoring: Coat color is classified along a continuum: yellow (unmethylated IAP), mottled (variegated methylation), and pseudoagouti (methylated IAP) [15]. This visible phenotype provides a non-invasive biomarker of the underlying epigenetic state.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Mammalian Metastable Epialleles

| Epiallele | Species | Associated Element | Phenotypic Manifestations | Inheritance Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agouti (Avy) | Mouse | IAP Retrotransposon | Coat color, obesity, diabetes, tumor susceptibility | Maternal bias [13] [14] |

| Axin Fused (AxinFu) | Mouse | IAP Retrotransposon | Tail kinking | Paternal transmission in 129 background [13] [15] |

| CabpIAP | Mouse | IAP Retrotransposon | Unknown | Responsive to BPA exposure [13] |

Beyond Agouti: Contemporary Mammalian Models

Paternal Methionine Supplementation in Sheep

Recent research has extended TEI investigations beyond rodent models to large mammals. A 2025 study examined the transgenerational effects of paternal methionine supplementation in sheep, providing compelling evidence for TEI across multiple unexposed generations [16]. Methionine serves as a crucial methyl group donor through its conversion to S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), the primary substrate for DNA methyltransferases [16].

This study implemented a robust experimental design using twin-pair F0 rams, with one twin receiving methionine supplementation and the other serving as a control. Researchers then tracked DNA methylation patterns and phenotypic traits across four generations (F0-F4) using whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) to identify differentially methylated cytosines (DMCs) and genes (DMGs) [16].

The findings demonstrated that a moderate dietary intervention in F0 rams induced transgenerational effects on growth and fertility-related phenotypes that persisted into the F3 and F4 generations, including significant effects on birth weight, weaning weight, post-weaning weight, loin muscle depth, and scrotal circumference [16]. Most notably, the study identified 41 DMGs exhibiting transgenerational epigenetic inheritance across four generations (TEI-DMGs) and 11 TEI-DMGs across all five generations, providing unprecedented molecular evidence for stable transgenerational inheritance of diet-induced epigenetic changes in a mammalian system [16].

Environmental Toxicants and Stress Models

Other contemporary models have expanded the range of environmental exposures known to induce transgenerational effects:

Endocrine Disruptors: The fungicide vinclozolin, when administered to gestating rats during gonadal sex determination, induces adult-onset disease states including infertility, immune abnormalities, and tumorigenesis that persist transgenerationally [2]. However, reproducibility concerns and strain-specific effects have been noted, highlighting the complexity of these phenomena [2].

Traumatic Stress: Parental trauma exposure can alter stress responses and behavior in subsequent generations. Children of Holocaust survivors show altered cortisol levels and DNA methylation patterns in the FKBP5 gene [11]. Similarly, maternal separation in mice induces depression-like behaviors and epigenetic changes in genes like MeCP2 and CRFR2 that persist for multiple generations [11].

Molecular Mechanisms and Mediators of TEI

DNA Methylation

DNA methylation represents the most extensively studied epigenetic mechanism in TEI. Cytosine methylation at CpG dinucleotides provides a relatively stable epigenetic mark that can be maintained through cell divisions via the activity of DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) [11]. The resistance of certain genomic regions, particularly those associated with retrotransposons like IAPs, to epigenetic reprogramming during germ cell development and early embryogenesis provides a potential mechanism for transgenerational persistence [13] [15].

However, evidence from the Avy model suggests that DNA methylation itself may not be the primary inherited mark. Studies examining DNA methylation in mature gametes, zygotes, and blastocysts found that methylation is entirely absent from the Avy locus in blastocysts following maternal transmission, despite clear epigenetic inheritance [15]. This indicates that another epigenetic feature must be carrying the heritable information.

Histone Modifications and RNA Mediators

Other potential molecular carriers of transgenerational epigenetic information include:

Histone Modifications: Post-translational modifications of histone tails (e.g., methylation, acetylation) can influence chromatin structure and gene expression. Certain histone marks may evade reprogramming or be re-established based on templating mechanisms [17].

Non-coding RNAs: Small non-coding RNAs, particularly those present in gametes (e.g., piRNAs, miRNAs), represent compelling candidates for epigenetic mediators. Sperm RNA from environmentally-exposed males can recapitulate phenotypic effects in offspring, and specific miRNAs have been implicated in transmitting the effects of environmental enrichment [11].

Histone Retention: In sperm, some histones are retained and carry modifications that may influence embryonic gene expression, though the extent and functional significance remain debated [5].

The following diagram illustrates the potential mechanisms whereby epigenetic information flows across generations, integrating the various molecular mediators discussed:

Critical Windows and Reprogramming Evasion

The establishment of transgenerationally heritable epigenetic marks depends on exposure during critical developmental windows, particularly during germ cell development and early embryogenesis when the epigenome is most plastic [13]. The differential susceptibility of specific genomic regions to epigenetic reprogramming represents a key determinant of transgenerational inheritance potential. Imprinted genes, metastable epialleles, and repetitive elements appear particularly prone to retaining epigenetic memory across generations [17].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Whole Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS)

For comprehensive methylation profiling, WGBS has become the gold standard:

Protocol Overview:

- DNA Extraction: High-quality genomic DNA is isolated from target tissues (e.g., liver, sperm).

- Bisulfite Conversion: DNA is treated with sodium bisulfite, converting unmethylated cytosines to uracils while leaving methylated cytosines unchanged.

- Library Preparation: Converted DNA is processed for next-generation sequencing with appropriate adapters.

- Sequencing: High-coverage sequencing is performed (typically >30x coverage for most CpGs).

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Reads are aligned to a reference genome, and methylation levels are calculated for each cytosine in a CpG context.

Applications in TEI Research: WGBS enables identification of inter-individual differentially methylated regions (iiDMRs) and metastable epialleles genome-wide, as demonstrated in studies of Avy mice and methionine-supplemented sheep [16] [12].

Germline Epigenome Analysis

Investigating TEI requires careful examination of germ cells to distinguish true germline transmission from somatic effects:

Sperm DNA Methylation Analysis: Protocol similar to WGBS but optimized for sperm DNA, which has unique packaging and methylation patterns.

Oocyte Epigenetic Profiling: Technically challenging due to limited material but critical for understanding maternal transmission.

Cross-Fostering Studies: Essential for distinguishing in utero effects from true germline transmission by transferring embryos or newborns to unexposed mothers.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for TEI Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use in TEI Research |

|---|---|---|

| Methylation-Sensitive Restriction Enzymes (HpaII) | Detection of methylated CpG sites | Southern blot analysis of Avy IAP methylation status [15] |

| Sodium Bisulfite | Chemical conversion of unmethylated cytosine to uracil | Bisulfite sequencing for single-base resolution methylation mapping [15] |

| DNA Methyltransferase Inhibitors | Experimental manipulation of DNA methylation | Investigating causal role of methylation in phenotype establishment |

| Histone Modification-Specific Antibodies | Immunoprecipitation of modified chromatin | ChIP-seq for genome-wide mapping of histone marks in germ cells |

| Small RNA Isolation Kits | Purification of piRNAs, miRNAs from limited samples | Analysis of sperm RNA cargo in paternal transmission models [11] |

| Methyl-Donor Compounds (Folic Acid, Betaine, Choline) | Nutritional manipulation of methylation capacity | Examining dietary protection against environmental toxicants [13] |

| Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals (BPA, Vinclozolin) | Environmental exposure models | Induction of epigenetic alterations in germ cells [13] [2] |

| Phytoestrogens (Genistein) | Natural compound exposure models | Demonstrating nutritional influence on fetal epigenome [13] |

| Whole Genome Bisulfite Sequencing Kits | Comprehensive methylation profiling | Identification of iiDMRs and metastable epialleles [16] [12] |

| Germ Cell Sorting Protocols | Isolation of pure populations of gametes | Cell-type specific epigenome analysis |

| ABT-702 dihydrochloride | ABT-702 dihydrochloride, CAS:1188890-28-9, MF:C22H21BrCl2N6O, MW:536.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Biperiden Hydrochloride | Biperiden Hydrochloride, CAS:1235-82-1, MF:C21H30ClNO, MW:347.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The Agouti mouse model has served as a foundational biosensor in environmental epigenetics, providing critical insights into how nutritional and environmental factors during development can shape the epigenome with lifelong and transgenerational consequences [13]. Contemporary studies in sheep and other mammalian models have confirmed that TEI is a biologically significant phenomenon with potential implications for understanding disease etiology and adaptation.

Significant challenges remain in the TEI field, including the need for standardized criteria to distinguish true transgenerational inheritance from intergenerational effects, better understanding of the molecular mechanisms that allow epigenetic information to survive reprogramming, and the development of high-throughput assays for screening environmental epigenotoxicants [2] [1]. Furthermore, the potential for reversal or mitigation of adverse transgenerational epigenetic effects through nutritional or pharmacological interventions represents a promising area for therapeutic development.

For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding TEI mechanisms has profound implications for disease risk assessment, therapeutic target identification, and the design of safer interventions that consider potential multigenerational impacts. As the field advances, integrating epigenetic inheritance into pharmacological models may open new avenues for preventing and treating complex diseases with both genetic and environmental components.

Distinguishing Transgenerational from Intergenerational Inheritance

In mammalian research, the precise distinction between intergenerational and transgenerational inheritance is fundamental yet frequently misunderstood. This distinction hinges on whether subsequent generations were directly exposed to the original environmental stressor or its physiological effects, or whether the inheritance occurs in the absence of any direct exposure [18]. Within the context of a broader thesis on transgenerational epigenetic inheritance in mammals, clarifying this terminology is not merely semantic; it is critical for establishing rigorous experimental designs and interpreting data on the transmission of acquired traits, particularly those involving epigenetic mechanisms such as DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNA signatures [7] [19].

The ongoing debate in the field concerns whether true transgenerational epigenetic inheritance, which must bypass two waves of epigenetic reprogramming in mammals, genuinely exists or whether most observed phenomena can be explained by intergenerational effects [2] [3]. This guide provides a technical framework for distinguishing these phenomena, detailing appropriate experimental models, and applying stringent evidence criteria essential for research and drug development professionals working in this contested area.

Core Conceptual Distinctions

Foundational Definitions

The transmission of phenotypic traits or molecular signatures across generations falls into distinct categories based on the route of exposure and the generations affected.