Standardizing Epigenetic Clock Analysis: A Cross-Tissue Framework for Reliable Biomarker Application

Epigenetic clocks have emerged as powerful tools for estimating biological age, yet their application is hampered by significant variability in predictions across different tissues.

Standardizing Epigenetic Clock Analysis: A Cross-Tissue Framework for Reliable Biomarker Application

Abstract

Epigenetic clocks have emerged as powerful tools for estimating biological age, yet their application is hampered by significant variability in predictions across different tissues. This article addresses the critical need for standardized protocols in epigenetic clock analysis to ensure reliable and reproducible results in research and drug development. We explore the foundational principles of epigenetic clocks, the sources of tissue-specific variation, and the latest methodological advancements for cross-tissue calibration. Drawing on recent 2025 research, we provide a comprehensive troubleshooting guide and evaluate emerging validation frameworks, including multi-clock ensemble approaches. This resource is tailored for scientists and pharmaceutical professionals seeking to implement robust, tissue-agnostic epigenetic biomarkers in aging and therapeutic intervention studies.

The Fundamental Challenge: Why Tissue Type Matters in Epigenetic Age Estimation

FAQs: Core Concepts and Definitions

What is an epigenetic clock? An epigenetic clock is a biochemical test that measures specific chemical modifications to a person's DNA, known as DNA methylation, to estimate biological age [1] [2]. These clocks are based on the predictable pattern in which small molecules called methyl groups are added to or removed from precise locations in our genome over time. While they can accurately estimate chronological age, their greater power lies in measuring biological age—how well your body’s cells and systems are functioning relative to your actual years [2].

What is the difference between chronological age, biological age, and epigenetic age?

- Chronological Age: The actual time a person has lived (the number of birthdays) [2].

- Biological Age: An estimate of how old a person seems based on the physiological condition of their cells and tissues [2].

- Epigenetic Age: The specific age estimate derived from DNA methylation patterns, which serves as a biomarker for biological age [2].

What are the different generations of epigenetic clocks? Epigenetic clocks have evolved through distinct generations, each with different training objectives and applications [2].

Table 1: Generations of Epigenetic Clocks

| Generation | Description | Key Example Clocks |

|---|---|---|

| First Generation | Trained to predict chronological age accurately across tissues or in specific sample types. | Horvath pan-tissue clock [3] [2], Hannum clock (blood-specific) [3] [2] |

| Second Generation | Trained on phenotypic data related to healthspan, mortality risk, and physiological decline. | PhenoAge [3] [2], GrimAge (predicts mortality) [3] [2] [4] |

| Third Generation | Designed to measure the pace of aging rather than cumulative damage; some are pan-mammalian. | DunedinPACE (pace of aging) [2], Pan-Mammalian clocks [2] |

What is a pan-tissue epigenetic clock? A pan-tissue epigenetic clock is a model designed to accurately estimate age using DNA methylation data from a wide variety of tissue and cell types from throughout the body. The most prominent example is the Horvath pan-tissue clock, developed in 2013, which uses 353 CpG sites to provide a age estimate that is highly accurate across 51 different tissues and cell types [3] [2] [5].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Challenge 1: Inconsistent or Misleading Clock Estimates Across Tissues

- Problem: Applying a clock trained on one tissue type (e.g., blood) to a different tissue type (e.g., buccal or saliva) yields age estimates that are not comparable, with differences of up to 30 years in some cases [6] [7].

- Root Cause: Differentiated cell types across body tissues exhibit unique DNA methylation landscapes and age-related alterations. Cellular composition significantly skews clock estimates [6] [8].

- Solution:

- Select Appropriate Clocks: For cross-tissue studies, use clocks specifically designed for this purpose.

- Validate with Tissue-Specific Clocks: When focusing on a specific tissue, use a clock trained on it. For example, use the PedBE clock for buccal cells from pediatric populations [5].

- Consider Ensemble Methods: Newer approaches like EnsembleAge integrate predictions from multiple individual clocks to enhance accuracy and consistency across diverse conditions [9].

Challenge 2: Interpreting Results from Anti-Aging Interventions

- Problem: An intervention appears to slow or reverse epigenetic aging according to a clock, but it is unclear if this reflects a genuine health improvement or a misleading biological signal [10].

- Root Cause: Not all age-related methylation changes have the same biological meaning. Some (Type 1) may be drivers of aging pathology, while others (Type 2) could represent the body's compensatory repair mechanisms. Suppressing Type 2 changes might make a clock "look younger" while actually harming health [10].

- Solution:

- Use Multiple Clocks: Do not rely on a single clock. Analyze results across first-, second-, and third-generation clocks (e.g., Horvath, GrimAge, DunedinPACE) to get a multi-dimensional view of the intervention's effects [3].

- Prioritize Phenotype-Linked Clocks: For health outcomes, place more weight on second-generation clocks like GrimAge and PhenoAge, which are trained specifically on mortality, morbidity, and clinical biomarkers [3] [2] [4].

- Correlate with Functional Metrics: Always correlate epigenetic age changes with other physiological and functional health biomarkers to ensure consistency [3].

Challenge 3: Selecting a Clock for Pediatric or Perinatal Research

- Problem: Standard epigenetic clocks, trained largely on adult data, may not perform optimally in infants and children [5].

- Root Cause: DNA methylation changes most rapidly during early development. Clocks trained on adults may not capture the unique methylation patterns of this life stage [5].

- Solution: Utilize clocks specifically developed for younger populations.

- Horvath Pan-Tissue & Skin/Blood Clocks: Designed for all ages and perform well in children [5].

- PedBE Clock: Developed specifically on buccal cells from individuals aged 0-20 years [5].

- Gestational Age Clocks: Use clocks like Knight's cord blood clock or Mayne's placental clock to estimate gestational age in newborns [5].

Table 2: Selecting an Epigenetic Clock for Your Experiment

| Research Context | Recommended Clock(s) | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Cross-Tissue Analysis | Horvath Pan-Tissue, Skin & Blood | The Skin & Blood clock showed greatest concordance in a direct comparison of 5 tissues [6]. |

| Mortality & Health Risk Prediction | GrimAge, PhenoAge | GrimAge is particularly noted for its strong prediction of lifespan and healthspan [3] [2]. |

| Measuring Pace of Aging | DunedinPACE | Useful for measuring the rate of aging rather than a static biological age [2]. |

| Buccal Cell Samples (Children) | PedBE Clock | Optimized for buccal cells and the pediatric age range [5]. |

| Blood Samples (Children) | Wu Clock, Horvath Skin & Blood | The Wu clock was developed specifically on whole blood from children [5]. |

| Clinical Trial of an Intervention | A Panel: Horvath, GrimAge, PhenoAge, DunedinPACE | Using multiple clocks provides a more robust and comprehensive assessment of intervention effects [3]. |

Standardized Experimental Protocol for Cross-Tissue Analysis

This protocol provides a step-by-step guide for researchers aiming to generate comparable epigenetic age estimates across different tissue types.

1. Sample Collection and Storage

- Tissue Types: Common types include buffy coat (leukocytes), Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs), dry blood spots (DBS), saliva, and buccal epithelial cells [6].

- Collection:

- Blood: Collect whole blood in EDTA tubes. Isolate buffy coat or PBMCs via density gradient centrifugation and freeze pellet at -80°C [3].

- Buccal/Saliva: Use commercially available collection kits. Ensure consistent collection time to control for diurnal variation.

- Storage: Store all DNA samples at -80°C to preserve methylation patterns.

2. DNA Extraction and Bisulfite Conversion

- Extraction: Use standardized kits (e.g., Qiagen DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit) for all samples to minimize batch effects.

- Quality Control: Assess DNA purity and concentration via spectrophotometry (e.g., Nanodrop). A 260/280 ratio of ~1.8 is ideal.

- Bisulfite Conversion: Treat extracted DNA using a kit such as the EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research). This converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils, while methylated cytosines remain as cytosines.

3. Methylation Array Processing

- Platform: Use the Illumina Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip for human samples, which interrogates over 850,000 CpG sites and includes the sites needed for all major clocks [3].

- Processing: Follow manufacturer's instructions. Scan arrays to generate raw intensity data (IDAT files).

4. Data Normalization and Preprocessing

- Pipeline: Process raw IDAT files using a standardized bioinformatics pipeline.

- Normalization: Apply a single-sample normalization method like ssNoob, which is recommended for integrating data from multiple batches or array types [8].

- Quality Checks: Exclude samples with low staining intensity, high detection p-values, or outlier behavior in multidimensional scaling plots.

5. Epigenetic Clock Calculation

- Software: Use available R packages (e.g.,

DNAmAgefor Horvath's clocks) or online portals (e.g., the Horvath Lab's DNAm Age Calculator). - Input: Submit normalized beta-values for all required CpG sites.

- Output: The software will return estimates for each requested clock (e.g., HorvathDNAmAge, HannumDNAmAge, DNAmGrimAge).

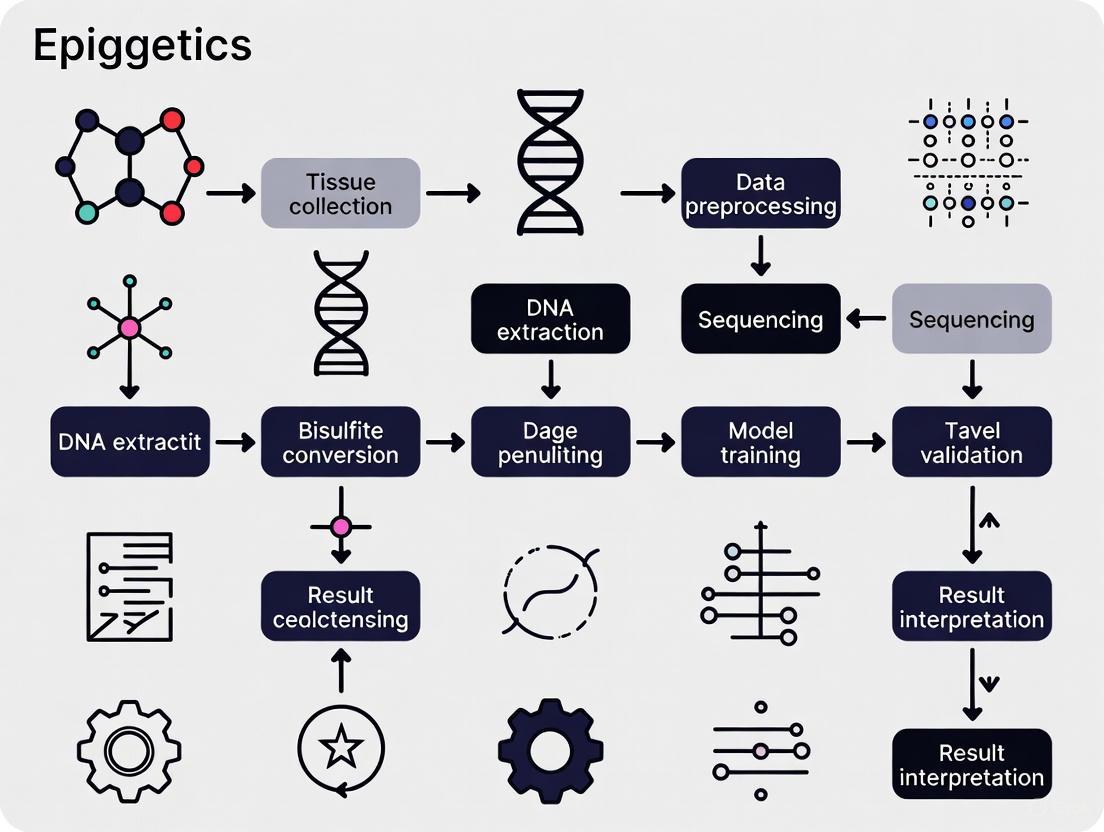

The following workflow diagrams the key steps and decision points in this protocol:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Application | Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Illumina Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip | Microarray for genome-wide DNA methylation analysis. Interrogates >850,000 CpG sites. | Essential platform for generating data compatible with all major epigenetic clocks [3]. |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kit | Chemically treats DNA to distinguish methylated from unmethylated cytosines. | A critical step before microarray analysis. EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research) is widely used [3]. |

| DNA Extraction Kit (Tissue Specific) | Isolves high-quality genomic DNA from various sample types. | Use kits optimized for specific tissues: DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen) for blood; Oragene•DNA (OG-500) for saliva [3]. |

| ssNoob Normalization | A single-sample normalization method for methylation array data. | Recommended for integrating data from multiple studies or array types; improves comparability [8]. |

| Reference Standards | Control DNA samples with known methylation profiles. | Used for quality control and batch correction (e.g., commercial reference DNA from Zymo Research or Illumina). |

| 3-Chloro-5-hydroxybenzoic Acid | 3-Chloro-5-hydroxybenzoic Acid, CAS:53984-36-4, MF:C7H5ClO3, MW:172.56 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 5-Hydroxydecanoic acid | 5-Hydroxydecanoic acid, CAS:624-00-0, MF:C10H20O3, MW:188.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Concepts: Emerging Methods and Cautions

Ensemble Clocks for Enhanced Robustness A persistent challenge is that different epigenetic clocks can yield inconsistent results for the same sample. To address this, ensemble methods like EnsembleAge have been developed. These tools integrate predictions from multiple individual clocks (e.g., built using ridge, lasso, and elastic net regression) to produce a more accurate and robust estimate of biological age, reducing false positives and negatives when evaluating interventions [9].

Functional Enrichment for Biological Interpretability Moving beyond purely predictive clocks, some researchers are building "functionally enriched" clocks by focusing on DNA methylation changes linked to specific hallmarks of aging, such as cellular senescence or dysregulated proliferation. This approach can provide deeper biological insights into the aging process and its association with diseases like cancer [8].

Critical Limitations and Future Directions

- Tissue Specificity is Paramount: The assumption that a blood-based epigenetic age reflects the age of all other tissues can be misleading. Studies show that aging can occur at different rates across tissues in the same individual, and diseases like cancer can be associated with discordant aging patterns across tissue types [8] [7].

- Not All Methylation is Equal: Be cautious in interpreting clock reversals. Some age-related methylation changes may represent the body's attempt at repair. An intervention that reversES these changes might appear beneficial on a clock but could actually be disrupting vital repair mechanisms [10].

- Standardization is Needed: The field requires larger studies with more tissue-specific DNA methylation data to refine existing clocks and develop new, more reliable organ-specific models [7].

Key Evidence of Tissue-Specific Discrepancies in Age Prediction

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does my epigenetic age estimate vary when I use the same clock on different tissues from the same individual? A1: This is a common finding. Different tissues have unique epigenetic landscapes and exhibit distinct rates of age-related methylation changes. Applying a clock trained on one tissue type (e.g., blood) to another (e.g., brain or liver) can introduce significant bias. One study found that applying blood-derived clocks to oral-based tissues could result in average differences of almost 30 years in age estimates [11].

Q2: Are "pan-tissue" clocks immune to tissue-specific discrepancies? A2: While multi-tissue or "pan-tissue" clocks are designed for broader application, they can still show performance variations across tissues. Research indicates that clocks trained on multiple tissue types still exhibit differences in mean age estimates and correlation with chronological age across different tissues [7] [12]. For the highest accuracy, a clock trained specifically on the tissue type you are studying is generally recommended [13].

Q3: What is the clinical significance of finding tissue-specific age acceleration? A3: Tissue-specific age acceleration can be a powerful indicator of pathology. For example, in breast cancer patients, cancer tissue shows accelerated epigenetic aging, while some non-cancerous surrogate tissues (like cervical samples) show decelerated aging [8]. This suggests that aging may occur at different rates across the body and that systemic aging patterns can be altered by disease.

Q4: Which epigenetic clock should I use for my pediatric tissue samples? A4: Clock performance varies significantly by tissue and developmental stage in pediatric samples. Evidence suggests:

- Placental samples: The Lee clock is superior [14].

- Pediatric buccal cells: The PedBE clock performs best [14].

- Children's blood cells: The Horvath clock is recommended [14]. Selecting a clock that was trained on a similar tissue type and age group is critical for accurate assessment.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent age predictions across tissues. | Using a clock trained on a different tissue type (e.g., blood clock on brain tissue). | Use a tissue-specific clock where available. If not, use a multi-tissue clock and be cautious in interpretation, noting its potential limitations in your specific tissue [15] [13]. |

| Poor correlation between predicted and chronological age. | The clock algorithm may not be optimized for your tissue type or the age range of your samples. | Verify the clock was trained on a similar age distribution. For older samples or specific tissues like brain, a specialized clock (e.g., cortical clock) dramatically outperforms general ones [15]. |

| High variability in age estimates within the same tissue group. | Technical batch effects or high cellular heterogeneity within your samples. | Use a standardized preprocessing pipeline (e.g., ssNoob normalization) suitable for integrating data from multiple sources [8]. Account for cell type composition in your analysis. |

| Inability to detect the effect of a known aging intervention. | The specific clock used may be insensitive to the intervention. | Consider using an ensemble approach like EnsembleAge, which combines multiple models to enhance sensitivity to both pro-aging and rejuvenating interventions [9]. |

The following tables consolidate empirical data demonstrating the extent and nature of tissue-specific discrepancies in epigenetic age prediction.

Table 1: Evidence from Direct Cross-Tissue Comparisons in Humans

| Study Description | Key Finding | Tissue Types Compared | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Within-person comparison of common clocks | Significant differences in epigenetic age estimates between oral and blood-based tissues; average differences up to ~30 years observed. | Buccal, saliva, dry blood spots, buffy coat, PBMCs | [11] |

| Application of 8 clocks to 9 tissue types from GTEx project | Mean DNAm age estimates varied substantially across tissue types for all clocks; correlations with chronological age were strongest in blood. | Lung, colon, prostate, ovary, breast, kidney, testis, muscle, blood | [12] |

| Development of a cortex-specific clock | A novel cortical clock dramatically outperformed previously existing clocks when applied to human brain cortex samples. | Cortex vs. Pan-tissue performance | [15] |

Table 2: Tissue-Type Performance of Universal Pan-Mammalian Clocks

| Tissue Type | Number of Species Sampled | Age Correlation (r) for Universal Relative Age Clock (Clock 2) |

|---|---|---|

| Whole Blood | 124 | 0.952 |

| Skin | 92 | 0.942 |

| Spleen | Not Specified | 0.982 |

| Liver | Not Specified | 0.963 |

| Kidney | Not Specified | 0.963 |

| Cortex | Not Specified | 0.957 |

| Cerebellum | Not Specified | 0.963 |

| Hippocampus | Not Specified | 0.954 |

Source: Adapted from [16] and its supplementary data.

Standardized Experimental Protocol for Cross-Tissue Clock Analysis

To ensure reproducible and comparable results when investigating epigenetic age across tissues, follow this standardized workflow:

Title: Standardized workflow for cross-tissue analysis

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Sample Collection & Storage:

- Collect target tissues using standardized protocols.

- Immediately snap-freeze tissue specimens in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C until DNA extraction.

- For human studies, ensure informed consent and IRB approval.

DNA Methylation Profiling:

- Extract high-quality DNA from all samples using a validated kit (e.g., DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit).

- Perform bisulfite conversion on 500 ng of DNA using a dedicated kit (e.g., EZ-96 DNA Methylation-Lightning Kit).

- Profile DNA methylation using the appropriate Illumina Infinium array (e.g., EPIC, 450K, or the Mammalian Methylation Array for cross-species studies).

Data Preprocessing (Critical Step):

- Process raw IDAT files using a standardized pipeline in R.

- Quality Control: Exclude probes with detection p-value > 0.01, cross-reactive probes, and probes containing SNPs.

- Normalization: Apply a single-sample normalization method like ssNoob to correct for technical variation and batch effects. This is crucial for integrating data from different studies or array batches [8].

- Convert β-values to M-values for statistical analysis due to their preferable properties [13].

Epigenetic Clock Application:

- Select appropriate epigenetic clocks based on your research question and tissue type. For a robust analysis, consider applying multiple relevant clocks (e.g., a pan-tissue clock, a tissue-specific clock, and an ensemble clock) [9].

- Calculate DNAm age for each sample using the selected clocks' published coefficients.

Data Analysis & Interpretation:

- Calculate age acceleration residuals by regressing DNAm age on chronological age for each tissue and clock combination.

- Use linear mixed models to compare age acceleration across tissues, accounting for within-individual correlations.

- Interpret findings in the context of the specific clocks used, as they capture different aspects of the aging process.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for Epigenetic Clock Research

| Item | Function / Application in Research | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Illumina Infinium MethylationEPIC Kit | Genome-wide DNA methylation profiling, covering over 850,000 CpG sites. | Standard platform for human studies. |

| Mammalian Methylation Array | Targets ~36,000 highly conserved CpGs for pan-species epigenetic aging studies. | Essential for cross-mammalian comparative studies [16]. |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kit | Converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils, enabling methylation quantification. | EZ-96 DNA Methylation-Lightning Kit. |

| ssNoob Normalization | A single-sample normalization method for correcting batch effects in DNAm data. | Part of standardized preprocessing pipelines [8]. |

| MethylGauge Benchmarking Dataset | A curated collection of DNAm data from 211 controlled perturbation experiments in mice. | Used for benchmarking and developing robust clocks like EnsembleAge [9]. |

| EnsembleAge Suite | Ensemble-based epigenetic clocks that integrate predictions from multiple models for enhanced robustness. | Recommended for improved sensitivity to interventions in mouse models [9]. |

Comparative Analysis of Blood vs. Buccal vs. Skin Tissue Reliability

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: Our lab obtained conflicting epigenetic age estimates from buccal and blood samples from the same individual. Which result should we trust?

A: This is a common issue, not necessarily an error. Different tissues have unique DNA methylation (DNAm) landscapes and age at different rates. A 2025 cross-tissue comparison study found that applying blood-derived clocks to buccal tissue can result in average differences of almost 30 years for some age clocks [6]. The "correct" result depends on your research objective and the clock used.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify the Clock's Origin: Check which tissue type your epigenetic clock was originally trained on. Clocks trained on blood (e.g., Hannum clock) will generally be more reliable for blood samples.

- Use a Multi-Tissue Clock: For cross-tissue comparisons, select a clock specifically designed for this purpose, such as the Skin and Blood clock, which demonstrated the greatest concordance across blood, buccal, and saliva in a 2025 study [6] [17].

- Do Not Mix Tissues: Never use a clock trained on one tissue type to make conclusions about the epigenetic age of another tissue type. Your findings should be interpreted within the context of the specific tissue measured.

Q2: We are planning a long-term aging study and want to use the least invasive sampling method. Is buccal tissue a reliable alternative to blood for epigenetic clock analysis?

A: Buccal tissue is an excellent, less-invasive alternative, but with critical caveats. Its reliability is highly dependent on using the correct tool. While first-generation clocks like the Horvath pan-tissue clock can be applied, they show significant variability when used on buccal samples [6]. For optimal results, it is recommended to use a next-generation clock specifically trained on buccal data, such as CheekAge [18] [19]. Even when applied to blood data, CheekAge has demonstrated a significant association with mortality, performing comparably to the blood-trained PhenoAge clock [19]. For chronological age estimation across diverse tissues, the Skin and Blood clock is a robust choice [6] [17].

Q3: Our research focuses on the relationship between accelerated aging and cancer. Are some tissues more informative than others for this specific question?

A: Yes, tissue choice is critical in cancer aging research. A 2025 study revealed discordant aging patterns across tissues in individuals with cancer [8]. For example, in breast cancer patients, cancer tissue itself showed accelerated epigenetic aging, while surrogate non-cancerous tissues like cervical samples showed a decelerated epigenetic age [8]. This suggests that systemic aging is complex and not uniform.

- Recommendation: The most informative approach may involve analyzing both the tissue-of-interest (e.g., breast tissue) and a surrogate tissue (e.g., blood or buccal) to understand both local and systemic aging effects. The functional enrichment of epigenetic clocks for hallmarks of cancer like senescence and proliferation can provide deeper biological insights [8].

Q4: For predicting age-related diseases, which generation of epigenetic clocks should we prioritize in our biomarker discovery pipeline?

A: Prioritize second- and third-generation clocks. A large-scale, unbiased 2025 comparison of 14 clocks against 174 disease outcomes concluded that second-generation clocks (e.g., PhenoAge, GrimAge) significantly outperformed first-generation clocks (e.g., Horvath, Hannum), which have limited applications in disease settings [20]. These advanced clocks showed particularly strong predictive power for respiratory, liver, and metabolic diseases. First-generation clocks remain suitable for estimating chronological age, but for healthspan and disease risk, the field has moved to next-generation models [20].

The following tables consolidate key quantitative findings from recent studies on cross-tissue reliability of epigenetic clocks.

Table 1: Cross-Tissue Performance of Selected Epigenetic Clocks (2025) [6]

| Epigenetic Clock | Original Training Tissue | Performance in Buccal Tissue | Performance in Blood Tissue | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hannum Clock | Blood | Low correlation with blood estimates | High Accuracy | Not recommended for buccal tissue. |

| Horvath Pan-Tissue | Multi-tissue | Significant differences vs. blood | Significant differences vs. buccal | Sub-optimal comparability for blood/buccal. |

| PhenoAge | Blood (Physiology) | Low correlation with blood estimates | High Accuracy | Not recommended for buccal tissue. |

| Skin & Blood Clock | Skin & Blood | High concordance | High concordance | Most reliable for cross-tissue (blood/buccal/skin) age estimation. |

| PedBE Clock | Buccal (Pediatric) | High Accuracy in Buccal | Not Designed For Blood | The specialist clock for buccal tissue, especially in young populations. |

Table 2: Predictive Performance of Clock Generations for Health Outcomes (2025) [20]

| Epigenetic Clock Generation | Example Clocks | Association with All-Cause Mortality (Hazard Ratio per SD) | Number of Bonferroni-Significant Disease Associations* | Key Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-Generation | Horvath, Hannum | Weaker associations | 9 | Estimating chronological age |

| Second-Generation | PhenoAge, GrimAge (v1/v2) | Stronger associations (e.g., GrimAge v2: HR=1.54) | 37 (for GrimAge v2) | Predicting morbidity & mortality |

| Third-Generation | DunedinPACE, DunedinPoAm | Strong associations (comparable to 2nd gen) | Comparable to 2nd gen | Measuring the pace of aging |

*Out of 174 diseases tested in the Generation Scotland cohort (n=18,859).

Experimental Protocols for Cross-Tissue Analysis

Standardized Protocol for Cross-Tissue Collection and DNA Methylation Analysis

This protocol is designed to minimize technical noise when comparing epigenetic ages across different tissues [6] [21].

1. Sample Collection

- Buccal Epithelial Cells: Collect using Isohelix SK1 swabs or equivalent. Firmly scrape the inside of the cheek with multiple swabs (e.g., eight) per participant to ensure sufficient yield. Store swabs immediately at -80°C in sealed bags [6] [21].

- Saliva: Collect using Oragene tubes (e.g., OGR-500). Ensure participants refrain from eating or drinking (except water) for at least one hour before collection. Upon collection, mix with stabilizing buffer, aliquot, and store at -80°C [6] [21].

- Blood:

- Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs): Collect whole blood in EDTA tubes. Isolate PBMCs via density-gradient centrifugation with Ficoll. Pellet and store at -80°C in a suitable buffer (e.g., PBS with EDTA and BSA) [6] [21].

- Dried Blood Spots (DBS): Apply approximately 200 µL of whole blood to a protein saver card (e.g., Whatman 903). Store in a sealed bag with desiccant at room temperature [6].

- Skin: The specific protocol for skin punch biopsies is detailed in the original Skin and Blood clock publication. Generally, samples are snap-frozen or placed in stabilizing solution for DNA extraction [17].

2. DNA Extraction and Methylation Profiling

- Extract DNA from all samples using a standardized, validated kit (e.g., Qiagen DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit) to maintain consistency.

- Perform DNA methylation profiling using the Illumina Infinium MethylationEPIC array (850k). This array provides comprehensive coverage and is the current standard for developing and applying new clocks [18] [17].

3. Data Preprocessing & Normalization

- Process raw IDAT files using a standardized pipeline. Preprocessing should include:

- Background correction and normalization. The single-sample Noob (ssNoob) method is recommended for integrating data from multiple studies or arrays [8].

- Probe filtering: Remove probes with a high detection p-value (>0.01), cross-reactive probes, and probes located on sex chromosomes if the analysis is not sex-specific.

- Account for cell type heterogeneity, a major confounder in epigenetic age estimation. Use reference-based (e.g., EpiDISH) or reference-free methods to estimate and adjust for cell composition in your models [6] [19].

4. Epigenetic Clock Calculation & Statistical Analysis

- Calculate epigenetic age using your selected clocks (e.g., Skin and Blood, CheekAge, GrimAge).

- Calculate Age Acceleration (AA) or Delta Age as the residual from a regression of epigenetic age on chronological age. This is your key metric for assessing biological aging independent of chronological age.

- For within-person, cross-tissue analyses, use paired statistical tests (e.g., paired t-tests, intraclass correlation coefficients) to assess the agreement between tissue estimates [6].

Experimental Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for a robust cross-tissue epigenetic aging study:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Cross-Tissue Epigenetic Clock Research

| Item | Function | Example Product/Catalog Number |

|---|---|---|

| Buccal Swab | Non-invasive collection of buccal epithelial cells. | Isohelix SK1 Swabs [6] [21] |

| Saliva Collection Kit | Non-invasive collection and stabilization of saliva DNA. | DNA Genotek Oragene OGR-500 [6] [21] |

| EDTA Blood Collection Tube | Prevents coagulation for PBMC isolation. | Standard K2EDTA or K3EDTA tubes [6] |

| Dried Blood Spot Card | Simple, stable storage for whole blood. | Whatman 903 Protein Saver Card [6] [21] |

| Ficoll-Paque | Density gradient medium for PBMC isolation. | Cytiva Ficoll-Paque PREMIUM [6] |

| DNA Extraction Kit | High-yield, high-quality DNA extraction from multiple tissues. | Qiagen DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit [21] |

| MethylationEPIC Array | Genome-wide DNA methylation profiling. | Illumina Infinium MethylationEPIC (850k) Array [18] |

| EpiDISH R Package | Reference-based algorithm for estimating cell type proportions from DNAm data. | R Package EpiDISH v2.16 [19] |

| 6(5H)-Phenanthridinone | 6(5H)-Phenanthridinone, CAS:1015-89-0, MF:C13H9NO, MW:195.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Lumichrome | Lumichrome, CAS:1086-80-2, MF:C12H10N4O2, MW:242.23 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why do I observe discordant epigenetic ages between different tissues from the same individual?

Discordant epigenetic aging between tissues is a recognized phenomenon, not necessarily an error. It can provide crucial biological insights. For instance, research has shown that in individuals with breast cancer, breast tissue exhibited accelerated epigenetic aging, while surrogate tissues like cervical samples showed decelerated aging [8]. This suggests that aging may occur at different rates across the body and that systemic effects of a disease can manifest differently in various tissues.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify Tissue Integrity: Confirm that the samples are not degraded and that the DNA quality is high for both tissues.

- Confirm Clock Applicability: Ensure that the epigenetic clock you are using has been validated for the specific tissues you are analyzing. Clocks trained on one tissue type may not perform accurately on another.

- Contextualize Biologically: Interpret the findings in the context of the individual's health status, disease history, and exposures. Discordance can be a meaningful result, reflecting tissue-specific aging dynamics [22].

FAQ 2: How can I account for cell-type heterogeneity when constructing or applying an epigenetic clock to a complex tissue?

Cell-type composition is a major confounder in epigenetic clock analysis. Bulk tissue analysis averages methylation signals across all constituent cells, masking cell-type-specific aging signatures. To address this, you must either physically isolate cell populations or use computational methods.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Cell Sorting: For constructing a new clock, use fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to isolate pure cell populations before DNA methylation analysis.

- Computational Deconvolution: When working with bulk tissue data, use bioinformatic tools (e.g., CIBERSORT, EpiDISH) to estimate cell-type proportions and adjust for them in your statistical models.

- Leverage Single-Cell Data: As a benchmark, utilize publicly available single-cell datasets. For example, a study on mouse brain neurogenic regions built separate, accurate aging clocks for oligodendrocytes, microglia, and neural stem cells, revealing that different cell types age at different rates [23].

FAQ 3: My epigenetic age predictions are highly accurate for chronological age but do not correlate with functional health measures. What is wrong?

This is a common limitation of clocks trained solely on chronological age. They are excellent at predicting time but may not fully capture biological age or health status.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Use a Second-Generation Clock: Transition from first-generation clocks (e.g., Horvath's pan-tissue clock) to second- or third-generation clocks like DNAmGrimAge or DNAmPhenoAge [22]. These clocks are trained on phenotypic data or mortality risk and are more strongly associated with functional decline, disease, and mortality.

- Develop a Custom Functional Clock: Train a new clock using a functional metric relevant to your tissue of interest. For example, a clock was trained on the proliferative capacity of neural stem cells as a measure of biological age in the brain, which more directly reflected the tissue's functional health [23].

FAQ 4: Where can I submit samples for rigorous epigenetic clock testing?

Specialized organizations provide testing services for researchers. The Clock Foundation offers a portal for submitting DNA or tissue samples. They provide testing using various platforms, including the Horvath Mammalian Array for preclinical studies (Mammal320K for mouse studies, Mammal40K for other mammals) and EPIC methylation arrays for human studies, along with quality control and statistical analysis [24].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Developing a Cell-Type-Specific Transcriptomic Aging Clock from Single-Cell RNA-Seq Data

This protocol is adapted from a study that built aging clocks for neurogenic regions of the brain [23].

Sample Collection and Single-Cell Sequencing:

- Collect tissue samples from a cohort of subjects (e.g., mice) across a wide range of ages to capture aging dynamics.

- Use a multiplexing technique (e.g., MULTI-seq) to pool samples from multiple subjects into a single sequencing run, reducing batch effects and cost.

- Perform single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) on the isolated cells.

Data Preprocessing and Cell-Type Identification:

- Perform quality control (QC) to remove low-quality cells and doublets.

- Demultiplex the samples to assign cells to individual subjects.

- Cluster cells and perform cell-type annotation using known marker genes to identify major cell populations (e.g., oligodendrocytes, microglia, neural stem cells).

Model Training (Chronological Age Clock):

- For each cell type, create meta-cells (e.g., "BootstrapCells") by randomly sampling a fixed number of cells (e.g., 15) per subject. This ensures each subject is equally represented.

- Train a regression model (e.g., lasso or elastic net) using the gene expression data from the meta-cells to predict the chronological age of the subjects.

- Validate the model's performance using a cross-cohort validation scheme, where the model is trained on some cohorts and tested on a completely held-out cohort.

Protocol 2: Cross-Tissue Analysis of Epigenetic Age Acceleration in a Disease Cohort

This protocol is based on a study investigating substance use disorders (SUD) in postmortem brain and blood samples [22].

Cohort and Sample Selection:

- Obtain matched tissue pairs (e.g., prefrontal cortex brain tissue and whole blood) from well-phenotyped donors, including disease cases and controls.

- Ensure detailed demographic, clinical, and pathological data is available for all subjects.

DNA Methylation Profiling:

- Isolate DNA from all tissue samples using a standardized kit (e.g., DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit).

- Bisulfite-convert 500 ng of DNA from each sample (e.g., using EZ DNA Methylation Kit).

- Hybridize the converted DNA onto a methylation array (e.g., Infinium Human MethylationEPIC BeadChip).

Data Processing and Clock Calculation:

- Preprocess raw data using a standardized pipeline with single-sample normalization (e.g., ssNoob) to integrate data from different batches or array types.

- Calculate multiple epigenetic clock estimates (e.g., DNAmAge, DNAmPhenoAge, DNAmGrimAge) for each sample.

- Calculate Age Acceleration Residual (AAR) by regressing biological age on chronological age and using the residuals in subsequent statistical models to compare disease groups and tissues.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of Key Epigenetic Clocks

| Clock Name | Training Basis | Number of CpG Sites | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horvath's Pan-Tissue Clock [22] | Chronological age (multiple tissues) | 353 | Highly accurate across most tissues; good for chronological age estimation. | Less correlated with mortality and functional health outcomes. |

| DNAmGrimAge [22] | Time-to-death and plasma proteins | - | Superior for predicting mortality and age-related diseases like cancer. | - |

| DNAmPhenoAge [22] | Clinical chemistry markers | - | Strongly associated with physiological dysregulation and healthspan. | - |

| Cell-Type-Specific Clock [23] | Single-cell transcriptomics per cell type | - | Reveals aging dynamics of specific cell lineages; high biological resolution. | Requires single-cell data; computationally intensive to develop. |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Resource | Function in Protocol | Example Product / Source |

|---|---|---|

| DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit [22] | Isolation of high-quality genomic DNA from both tissue and blood samples. | Qiagen (Cat. 69504) |

| Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip [22] | Genome-wide DNA methylation profiling, covering over 850,000 CpG sites. | Illumina |

| EZ DNA Methylation Kit [22] | Bisulfite conversion of DNA, a critical step before methylation array hybridization. | Zymo Research |

| Horvath Mammalian Array [24] | DNA methylation platform for preclinical studies (e.g., Mammal320K for mice). | Clock Foundation |

| MULTI-seq Lipids [23] | Multiplexing samples for single-cell RNA-seq, reducing batch effects and cost. | - |

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Single-Cell Aging Clock Workflow

Diagram 2: Cross-Tissue Age Acceleration

The Promise and Limitations of Universal Mammalian Clocks

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQ

This technical support center addresses common challenges researchers face when applying universal mammalian epigenetic clocks across diverse tissues and species. The guidance is framed within the broader goal of standardizing epigenetic clock analysis protocols.

Table 1: Frequently Asked Questions and Evidence-Based Solutions

| Question | Issue Description | Evidence-Based Solution | Key Citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clock-Tissue Mismatch | Applying blood-trained clocks to oral/buccal tissues yields large age discrepancies (up to 30 years). | Use tissue-appropriate clocks. The Skin and Blood clock shows greatest cross-tissue concordance. For buccal samples, consider the PedBE clock. | [11] [6] |

| Training Data Quality | Inaccurate age records in calibration data lead to unreliable epigenetic clocks. | Ensure training age error is <22%. Beyond this threshold, prediction error increases with a small but significant effect size (Cohen's d >0.2). | [25] |

| Interpreting Age Acceleration | Discordant aging patterns in different tissues from the same individual (e.g., cancer patients). | Recognize that aging is tissue-specific. Profile multiple tissues if possible. In breast cancer, tumor tissue is older, while surrogate cervical tissue is younger. | [8] |

| Clock Selection | Choosing between 1st generation (Horvath) and 2nd generation (GrimAge, PhenoAge) clocks. | Horvath: Pan-tissue, good for chronological age. GrimAge/PhenoAge: Superior for healthspan, mortality, and disease risk prediction. | [26] [27] |

| Species Applicability | Applying universal clocks to non-model mammalian species. | Universal mammalian clocks exist for >150 species (dogs, cats, whales). Ensure the clock was trained on a relevant phylogenetic range. | [28] |

Data Presentation: Quantitative Comparisons

Table 2: Cross-Tissue Performance of Selected Epigenetic Clocks

This table synthesizes quantitative data on clock performance across different tissue types, based on empirical comparisons from recent studies. MAE stands for Mean Absolute Error.

| Epigenetic Clock | Primary Training Tissue | Buccal Epithelium Performance | Saliva Performance | Blood Performance (DBS/Buffy Coat) | Key Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horvath Pan-Tissue | Multi-tissue | Low correlation with blood estimates | Low correlation with blood estimates | High accuracy | Avoid applying blood estimates to oral tissues [6] |

| Hannum Clock | Whole Blood | Not Recommended | Not Recommended | MAE: ~3.9 years | High performance in blood, poor cross-tissue concordance [26] [6] |

| Skin & Blood Clock | Skin, Blood | High Concordance | High Concordance | High Concordance | Best overall for cross-tissue age estimation [11] [6] |

| PhenoAge | Phenotypic Age | Moderate correlation | Moderate correlation | High accuracy | Better for biological age/health risk than pure chronological age [26] [27] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standardized DNA Methylation Data Preprocessing

This protocol is essential for ensuring data consistency across studies and is based on a standardized pipeline used in recent functional clock research [8].

- Raw IDAT Processing: Use a standardized pipeline (e.g., based on

minfiandChAMPpackages in R). - Normalization: Apply ssNoob (single-sample Noob) normalization. This method is recommended for integrating data from multiple generations of Infinium arrays (27K, 450K, EPIC) and different experimental batches [8].

- Quality Control: Implement rigorous QC steps including background correction, dye-bias correction, and removal of poorly performing probes.

- Species Adaptation: For non-human mammals, use species-specific manifest and annotation files (e.g.,

IlluminaMouseMethylationmanifest) [8].

Protocol 2: Constructing a Functionally Enriched Epigenetic Clock

This methodology moves beyond purely chronological prediction to capture specific biological processes like senescence and proliferation [8].

Identify Process-Associated CpGs:

- Data Leveraging: Use publicly available DNA methylation datasets from experimental perturbations (e.g., GSE112812 for senescence, GSE197545 for proliferation inhibition).

- Statistical Modeling: For each CpG site, fit a linear model of methylation beta value against the condition (e.g., senescent vs. control), accounting for technical covariates like cell type and dataset.

- Site Selection: Retain autosomal CpGs significantly associated with the biological process after False Discovery Rate (FDR) adjustment (p < 0.05).

Calculate Clock Value: The clock value is computed as a weighted mean of methylation levels, accounting for the directionality of change: [ {clock}=\frac{{\sum}{i}^{n}(w* \beta )}{n} ] where (w{i...n}) represents the directionality weight (+1 for hypermethylation, -1 for hypomethylation in the condition), (\beta_{i...n}) represents the methylation value of the CpG, and (n) is the total number of CpGs in the clock [8].

Validation:

- Correlate the clock value with independent markers of the biological process (e.g., correlate a senescence clock with

CDKN2A (p16)mRNA expression, or a proliferation clock withMKI67 (Ki67)mRNA expression) using independent data from sources like TCGA [8].

- Correlate the clock value with independent markers of the biological process (e.g., correlate a senescence clock with

Visualizing Experimental Workflows

Diagram: Cross-Tissue Clock Analysis Workflow

Diagram: Functionally Enriched Clock Construction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Resources for Epigenetic Clock Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Illumina Methylation Arrays | Genome-wide DNA methylation profiling. | Infinium MethylationEPIC v2.0 array provides broadest coverage for human studies. Species-specific arrays available. |

| Standardized Preprocessing Pipeline | Ensure consistent data quality and normalization across studies. | Pipelines utilizing minfi and ChAMP in R; ssNoob for single-sample normalization is critical for batch integration [8]. |

| Reference Datasets | Identify functionally enriched CpG sites; validate clocks. | GEO Datasets: Senescence (GSE112812), Proliferation (GSE197545), Reprogramming (GSE54848) [8]. |

| Tissue-Specific Clock Algorithms | Accurate age estimation in specific tissues. | Skin & Blood clock: Best for cross-tissue use. PedBE clock: For buccal samples. Horvath clock: Pan-tissue baseline [11] [6]. |

| Universal Mammalian Clock Resources | Apply epigenetic aging to non-human species. | Resources from the Clock Foundation provide access to clocks for over 150 mammalian species [28]. |

| 9-Methoxycamptothecin | 9-Methoxycamptothecin, CAS:39026-92-1, MF:C21H18N2O5, MW:378.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| ABT-255 free base | ABT-255 free base, CAS:181141-52-6, MF:C21H24FN3O3, MW:385.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Methodological Framework: Best Practices for Cross-Tissue Clock Implementation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the core trade-off between accessible and target tissues in epigenetic clock studies?

The core trade-off lies between analytical convenience and biological relevance. Accessible tissues like blood (buffy coat, peripheral blood mononuclear cells) or saliva are collected minimally invasively, facilitating larger sample sizes and longitudinal studies. However, age-related methylation patterns are often tissue-specific. Applying a clock trained on blood to a different target tissue (e.g., brain or liver) can introduce significant bias and reduce predictive accuracy [11] [13]. One study found that applying blood-derived clocks to oral-based tissues (buccal, saliva) resulted in age estimate differences of almost 30 years in some cases [11]. For disease-specific research, the ideal scenario is to use the affected tissue, but accessible surrogate tissues provide a practical, though sometimes less accurate, alternative.

FAQ 2: When is it acceptable to use a multi-tissue clock, and when is a tissue-specific clock necessary?

Multi-tissue clocks (e.g., Horvath's original clock) are valuable when your research question involves estimating a organism-level or systemic biological age, or when directly obtaining the tissue of interest is ethically or practically impossible [26]. They provide a good general overview.

However, tissue-specific clocks are often superior for detecting subtle, pathology-specific aging signals within a particular organ [13]. Quantitative analyses indicate that elastic-net regression-based clocks trained on a specific tissue consistently outperform generic blood clocks when applied to samples from that same tissue [13]. Therefore, if your study focuses on a specific organ's aging (e.g., brain aging in Alzheimer's disease) and the tissue is available, a tissue-specific model is the more powerful and sensitive choice.

FAQ 3: Our study involves a rare disease with no existing tissue-specific clock. What is the best practical approach?

In this scenario, a tiered strategy is recommended:

- Prioritize High-Quality, Accessible Samples: Use a well-validated, population-appropriate multi-tissue clock on easily obtainable samples like blood or saliva. The Skin and Blood clock has shown greater concordance across blood and oral tissues than many other models and may be a robust starting point [11].

- Benchmark with Public Data: If possible, identify and process public DNA methylation datasets from healthy samples of your target tissue (if available) using the same multi-tissue clock. This will help you establish a baseline and understand the expected "age acceleration" in healthy tissue for comparison.

- Consider an Ensemble Approach: Emerging methods like EnsembleAge integrate predictions from multiple individual clocks, which can enhance robustness and reduce false positives, especially in challenging scenarios with limited data [9].

- Clearly Acknowledge the Limitation: In your reporting, explicitly state the use of a surrogate tissue and multi-tissue clock as a limitation, framing the findings as a preliminary assessment of systemic, rather than tissue-specific, epigenetic aging.

FAQ 4: We are seeing high variability in epigenetic age estimates from saliva samples. How can we improve reliability?

Saliva's variable cellular composition (a mix of epithelial and immune cells) is a common source of technical noise [29]. To improve reliability:

- Account for Cellular Heterogeneity: Use bioinformatic tools (e.g., reference-based deconvolution methods) to estimate and adjust for cell type proportions in your statistical models. This is a critical step for saliva and blood.

- Leverage Optimized Clocks: Explore clocks specifically validated or trained on saliva. For example, the EpiAgePublic clock, which uses only three CpG sites from the ELOVL2 gene, has been tested on saliva and performs on par with more complex models, potentially offering a more robust solution for this tissue type [29].

- Ensure Standardized Collection: Follow a standardized saliva collection protocol (e.g., time of day, fasting state) to minimize pre-analytical variability.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: A blood-derived epigenetic clock yields highly inaccurate and inconsistent age estimates when applied to buccal swab samples.

- Potential Cause 1: Fundamental Tissue Difference. The clock is capturing blood-specific methylation patterns that do not translate to the buccal epigenome [11].

Solution:

- Verify with a Pan-Tissue Clock: Apply a true multi-tissue clock (e.g., Horvath's clock) to your buccal samples. If the estimates become more accurate, the issue was tissue incompatibility.

- Switch to a Tissue-Specific or Compatible Clock: If available, use a clock trained on buccal or epithelial tissues. If not, the Skin and Blood clock is a better alternative [11].

- Re-calibrate Expectations: Acknowledge that the absolute epigenetic age value from a surrogate tissue may not match chronological age perfectly; focus on the "age acceleration" relative to a control group analyzed on the same tissue and with the same clock.

Potential Cause 2: Uncontrolled Cellular Heterogeneity. The proportion of different cell types in your buccal samples varies widely across individuals, introducing confounding variation [27].

- Solution: Perform cell type deconvolution on your methylation data to estimate the proportions of epithelial cells, immune cells, etc. Include these proportions as covariates in your downstream analysis to statistically adjust for the composition effect.

Problem: An intervention shows a significant effect on epigenetic age in liver tissue but no effect in blood.

- Potential Cause: Tissue-Specific Mechanism. The intervention may have a direct, potent effect on the liver that is not reflected systemically, or the signal in blood is too diluted to detect with your sample size [8].

- Solution:

- Interpret this as a Biological Finding: This discordance is a valid and interesting result, suggesting the intervention's primary effect is on the liver. This is supported by research showing discordant aging patterns across tissues in the same individual, such as in breast cancer patients [8].

- Strengthen the Evidence:

- Confirm the result using a liver-specific epigenetic clock if available.

- Correlate the liver epigenetic age acceleration with functional or histological markers of liver aging.

- A power analysis on blood samples from a pilot study can determine if a larger cohort might detect a smaller, systemic effect.

Problem: Different epigenetic clocks give conflicting results for the same set of samples.

- Potential Cause: Clock-Specific Biases. Different clocks are trained on different datasets (tissues, populations) and optimized for different objectives (chronological age vs. phenotypic age vs. mortality risk) [26] [27]. For instance, Horvath's clock is a pan-tissue chronological estimator, while PhenoAge incorporates clinical biomarkers.

- Solution:

- Understand Clock Design: Create a table summarizing the purpose (chronological vs. biological), training tissue, and strengths of each clock you are using.

- Use an Ensemble Method: Employ a framework like EnsembleAge, which aggregates predictions from multiple high-performing clocks to produce a more robust and consensus estimate of biological age, thereby mitigating the bias of any single model [9].

- Align Clock with Hypothesis: Choose the clock that best matches your research question. For example, use GrimAge or PhenoAge if you are studying healthspan-related outcomes, not just chronological age [26] [27].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol 1: Cross-Tissue Clock Performance Validation

Purpose: To empirically validate whether a candidate epigenetic clock performs adequately on a target tissue before committing to a large-scale study.

Steps:

- Data Acquisition: Obtain a publicly available DNA methylation dataset (e.g., from GEO) for your target tissue, with documented chronological ages for all samples.

- Data Preprocessing: Preprocess the data (normalization, quality control) using a standardized pipeline, such as

ssNoobfor single-sample normalization, which is suitable for integrating data from different arrays and studies [8]. - Age Estimation: Apply the candidate clock(s) to the preprocessed data to generate DNA methylation age (DNAmAge) estimates.

- Validation Analysis:

- Calculate the correlation (Pearson R) between DNAmAge and chronological age.

- Calculate the median absolute error (MAE) between DNAmAge and chronological age.

- Fit a linear model:

DNAmAge ~ Chronological Age. A strong clock will have a high R², a low MAE, and a slope close to 1.

The table below summarizes typical performance metrics for various clock types in their intended tissues, based on published literature [26] [30] [31]:

| Clock Name | Primary Tissue | Typical Correlation (R) with Chronological Age | Typical Median Absolute Error (MAE) | Key Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hannum Clock | Blood | ~0.96 | ~3.9 years | Optimized for blood; not for other tissues. |

| Horvath Clock | Multi-tissue | ~0.99 (training) | ~3.6 years | Good baseline for pan-tissue estimation. |

| Elastic Net Mouse Clock | Mouse Multi-tissue | 0.82 - 0.89 (cross-validation) | 2.5 - 1.8 months | An example of a high-performance model for mice. |

| EpiAgePublic | Blood, Saliva | On par with Horvath/DNAmPhenoAge | Not specified | Minimalist clock (3 CpGs); good for NGS and saliva. |

| Feature Selection Clocks [30] | Blood | R² > 0.87 | ~3.1 years | Built with 35 CpGs; can outperform Hannum/Horvath in validation. |

Protocol 2: A Workflow for Selecting the Optimal Tissue and Clock

This workflow diagram outlines a logical decision-making process for researchers designing an epigenetic clock study.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application in Epigenetic Clock Research |

|---|---|

| Illumina MethylationEPIC BeadChip | Industry-standard microarray for profiling DNA methylation at ~850,000 CpG sites. Provides broad, consistent coverage across samples. [13] |

| Mammalian Methylation Array | A microarray designed to target evolutionarily conserved CpGs, enabling cross-species aging studies (e.g., human-mouse translation). [9] [26] |

| Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS) | A sequencing-based method that enriches for CpG-dense regions. Cost-effective for genome-wide methylation analysis but can have missing data. [31] |

| Targeted Bisulfite Sequencing Panels | Next-generation sequencing assays (e.g., TIME-seq) focusing on a small, predefined set of CpGs (e.g., for EpiAgePublic). Cost-effective for large studies. [30] [29] |

| ssNoob Normalization | A single-sample normalization method for methylation arrays. Crucial for integrating datasets from different studies or array platforms. [8] |

| Cell Type Deconvolution Algorithms | Bioinformatic tools (e.g., based on reference methylomes) to estimate cell proportions in a tissue sample, critical for adjusting for cellular heterogeneity. [27] |

| EnsembleAge Framework | A software/model suite that combines predictions from multiple epigenetic clocks to produce a more robust and accurate estimate of biological age. [9] |

| Acarbose | Acarbose, CAS:56180-94-0, MF:C25H43NO18, MW:645.6 g/mol |

| Almorexant | Almorexant, CAS:871224-64-5, MF:C29H31F3N2O3, MW:512.6 g/mol |

Epigenetic clocks are powerful algorithms that predict biological age and health-related phenotypes based on DNA methylation (DNAm) patterns. However, their performance is highly dependent on the biological context in which they are applied. Most clocks were developed using DNAm data derived primarily from blood cells, which limits their accuracy when applied to other tissue types. This technical guide addresses the crucial challenge of selecting and applying epigenetic clock algorithms to diverse tissue types, providing troubleshooting and standardized protocols for researchers working to measure biological aging across different organ systems.

Recent research demonstrates that epigenetic clocks exhibit substantial variation in their age estimates across different tissues. A comprehensive 2025 study analyzing nine human tissue types found that for each clock, the mean DNAm age estimate varied significantly across tissues, and the correlation with chronological age was strongest in blood for most clocks [32] [12]. This tissue-specific performance underscores the importance of aligning algorithm selection with tissue type to generate accurate, biologically meaningful results in epigenetic aging studies.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Challenges in Cross-Tissue Epigenetic Analysis

FAQ 1: Why does my epigenetic age estimate vary dramatically when applying the same clock to different tissues from the same donor?

Issue: Significant discrepancies in age estimates across tissues from the same individual using identical clock algorithms.

Explanation: This is an expected finding rather than a technical error. Different tissues exhibit unique epigenetic aging patterns due to variations in cell composition, replication rates, exposure to environmental stressors, and tissue-specific functions [32] [33]. For example, a study of multiple clocks across 9 tissue types found that mean DNAm age estimates varied substantially across lung, colon, prostate, ovary, breast, kidney, testis, skeletal muscle, and whole blood tissues [32].

Solutions:

- Interpret tissue-specific differences biologically: Differences may reflect genuine variations in biological aging rates across tissues rather than measurement error.

- Select tissue-appropriate clocks: Use clocks specifically validated for your tissue of interest when available.

- Apply multiple clocks: Compare results across different epigenetic clocks to identify consistent patterns.

- Account for cell composition: Include cell type heterogeneity in your analysis model where possible.

FAQ 2: Why does my epigenetic clock show poor correlation with chronological age in non-blood tissues?

Issue: Weak correlation between predicted epigenetic age and chronological age in certain tissue types.

Explanation: Most epigenetic clocks were trained primarily on blood-derived DNAm data, optimizing their performance for blood tissue [33]. When applied to other tissues, their accuracy naturally decreases. Research shows that blood often demonstrates the strongest correlation with chronological age across multiple clock types [32].

Solutions:

- Verify clock training data: Consult original publications to determine which tissues were used for clock development.

- Consider pan-tissue clocks: Algorithms like the Horvath pan-tissue clock were specifically designed for cross-tissue application [34].

- Explore tissue-specific adjustments: Some researchers have developed calibration methods for specific tissues.

- Assess statistical significance: Even with weaker correlations, age acceleration (difference between epigenetic and chronological age) may still provide valuable biological insights.

FAQ 3: How do I resolve conflicting age acceleration results when comparing different clocks on the same tissue samples?

Issue: Different clocks yield contradictory age acceleration estimates for the same tissue samples.

Explanation: Epigenetic clocks capture distinct aspects of the aging process. First-generation clocks (e.g., Horvath, Hannum) estimate chronological age, while newer generations (e.g., PhenoAge, GrimAge, DunedinPACE) incorporate additional health-related biomarkers and predict mortality risk [32] [22]. Each clock utilizes different CpG sites and algorithmic approaches, leading to varying results.

Solutions:

- Understand clock purposes: Align clock selection with your research question (chronological age prediction vs. health risk assessment).

- Reference published comparisons: Consult studies that have systematically compared multiple clocks across tissues [32].

- Report multiple metrics: When uncertain, present results from several complementary clocks.

- Prioritize biological validation: Correlate epigenetic age acceleration with relevant functional or clinical outcomes specific to your tissue of interest.

Quantitative Performance Data: Epigenetic Clock Comparisons Across Tissues

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of Epigenetic Clocks Across Tissue Types

| Clock Algorithm | Primary Training Tissue | Best Performing Tissues | Key Applications and Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Horvath | Multi-tissue (~8,000 samples) | Pan-tissue application | Estimates chronological age; 353 CpGs; 23 missing in EPIC array [32] |

| Hannum | Whole blood (656 samples) | Whole blood | Estimates chronological age; 71 CpGs; 9 missing in EPIC array [32] |

| PhenoAge | Whole blood (9,926 samples) | Whole blood | Predicts healthspan, mortality risk; incorporates clinical parameters [32] |

| EpiTOC | Multiple | Tissues with high cell turnover | Estimates mitotic age, stem cell divisions; cancer risk assessment [32] |

| DunedinPACE | Longitudinal biomarker data | Blood, multiple tissues | Estimates pace of aging; 173 CpGs; developed from longitudinal data [32] |

| EpiClock | Multiple | Multiple, optimized for EPIC array | 7,000 CpGs; improved accuracy on EPIC platform data [32] |

| AltumAge | Multiple | Multiple, optimized for EPIC array | 20,318 CpGs; uses extensive CpG sites for prediction [32] |

| Zhang Clock | Multiple | Multiple | 514 CpGs; balances CpG number and prediction accuracy [32] |

Table 2: Tissue-Specific Considerations for Epigenetic Clock Application

| Tissue Type | Key Aging Characteristics | Recommended Clocks | Special Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Blood | Strong correlation with chronological age for most clocks | Hannum, PhenoAge, GrimAge | Most validated tissue; cell composition effects important |

| Lung | Shows positive association with smoking exposure | Horvath, PhenoAge, DunedinPACE | Environmental exposures significantly impact aging [32] |

| Breast | Shows accelerated aging in cancer tissue | Functionally enriched clocks | Cancer context important for interpretation [8] |

| Brain (Prefrontal Cortex) | Shows different aging patterns in substance use disorders | Horvath, DNAmTL | Blood-brain correlation limited; tissue-specific effects [22] |

| Colon | High cell turnover affects aging metrics | EpiTOC, Horvath | Mitotic activity influences epigenetic age estimates |

| Testis | Unique aging biology | Pan-tissue clocks | Shows distinct aging pattern from somatic tissues [32] |

| Muscle | Age-related functional decline | Horvath, PhenoAge | Correlate with functional measures when possible |

Experimental Protocols: Standardized Workflow for Cross-Tissue Clock Analysis

Sample Processing and DNA Methylation Measurement

Protocol Objective: To generate high-quality DNA methylation data from diverse tissue types for epigenetic clock analysis.

Materials and Reagents:

- Tissue samples (snap-frozen or preserved in DNA/RNA stabilizing solutions)

- DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen) or equivalent DNA extraction system

- EZ-96 DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research) for bisulfite conversion

- Infinium MethylationEPIC v1.0 BeadChip (Illumina) or equivalent platform

- Quality control metrics: Nanodrop, agarose gel electrophoresis, or Bioanalyzer

Methodology:

- DNA Extraction: Isolate genomic DNA from approximately 500mg of tissue using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit following manufacturer's protocols [22].

- DNA Quantification and Quality Assessment: Measure DNA concentration and purity (260/280 ratio >1.8, 260/230 ratio >2.0). Confirm DNA integrity via gel electrophoresis.

- Bisulfite Conversion: Convert 500ng of DNA using the EZ-96 DNA Methylation Kit, following manufacturer's guidelines [32].

- Methylation Array Processing: Process samples on the Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip according to standard Illumina protocols.

- Quality Control Checks: Assess bisulfite conversion efficiency, staining intensity, and hybridization controls using platform-specific metrics.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- For fatty tissues, additional purification steps may be necessary to remove lipids that interfere with DNA extraction.

- When working with limited tissue quantities, consider whole-genome amplification prior to bisulfite conversion, though this may introduce bias.

- Ensure samples are randomly distributed across arrays to avoid batch effects.

Data Preprocessing and Normalization

Protocol Objective: To process raw DNA methylation data into normalized beta values suitable for epigenetic clock calculation.

Computational Tools:

- R programming environment with specialized packages (ChAMP, minfi, watermelon)

- BMIQ (Beta Mixture Quantile) normalization for probe-type bias correction

- ssNoob (single-sample normal-exponential out-of-band) background correction

Methodology:

- Data Import: Load raw IDAT files into R using the minfi or ChAMP packages [32] [8].

- Background Correction: Apply ssNoob method with dye bias correction to adjust for technical background noise [32].

- Normalization: Perform BMIQ normalization to correct for type I/II probe design biases [32].

- Quality Filtering: Remove probes with detection p-value >0.01, cross-reactive probes, and probes containing SNPs at the CpG site or single-base extension position.

- Beta Value Calculation: Compute methylation beta values ranging from 0 (completely unmethylated) to 1 (completely methylated).

Troubleshooting Notes:

- For studies combining data from different array platforms (27K, 450K, EPIC), limit analysis to the 24,677 overlapping CpG sites [34].

- Check for sample outliers using principal component analysis (PCA) and remove samples deviating significantly from tissue cluster [32].

- Address batch effects using ComBat or other batch correction methods when samples were processed across different dates or plates.

Epigenetic Clock Calculation and Statistical Analysis

Protocol Objective: To compute epigenetic age estimates and analyze age acceleration patterns across tissues.

Computational Resources:

- Epigenetic clock calculators (Horvath's online calculator, R packages)

- Statistical software (R, Python with appropriate libraries)

Methodology:

- Clock Implementation: Calculate epigenetic age using published algorithms and code:

- Age Acceleration Calculation: Compute age acceleration residuals by regressing epigenetic age on chronological age across your sample set.

- Cross-Tissue Correlation: Assess correlations of epigenetic age estimates across different tissues from the same donors.

- Association Analysis: Test relationships between epigenetic age acceleration and participant characteristics (e.g., smoking, BMI, disease status) using linear models adjusted for appropriate covariates.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- When clock CpGs are missing from your dataset (common with older clocks on EPIC arrays), consult original publications for imputation strategies or use updated clocks [32].

- For multi-tissue studies, use mixed-effects models to account for within-donor correlations across tissues.

- Adjust for key technical covariates like array row/column position and bisulfite conversion efficiency.

Visual Workflows: Cross-Tissue Epigenetic Clock Analysis Pipeline

Workflow for Cross-Tissue Epigenetic Clock Analysis

Decision Tree for Epigenetic Clock Selection

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Cross-Tissue Epigenetic Analysis

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Epigenetic Clock Studies

| Category | Specific Product/Tool | Application Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction | DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen) | High-quality DNA isolation from diverse tissues | Consistent yield across tissue types; effective removal of inhibitors |

| Bisulfite Conversion | EZ-96 DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research) | Convert unmethylated cytosines to uracils | High conversion efficiency (>99%); minimal DNA degradation |

| Methylation Arrays | Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip (Illumina) | Genome-wide methylation profiling at 866,895 CpG sites | Coverage of clock-relevant CpGs; platform-specific normalization needed |

| Data Processing | ChAMP R package | Comprehensive methylation data analysis | Includes normalization, QC, and batch effect correction [32] |

| Data Processing | BMIQ Normalization | Probe-type bias adjustment | Essential for combining Infinium I and II probes [32] |

| Data Processing | ssNoob Method | Background correction | Single-sample method suitable for incremental data processing [8] |

| Clock Calculation | Horvath's Epigenetic Clock Calculator | Multi-tissue age estimation | Online tool or R code for multiple clocks [32] |

| Reference Data | GTEx Project Dataset | Multi-tissue reference epigenomes | 973 samples across 9 tissues for comparison [32] |

| Quality Metrics | Methylation Array Control Metrics | Monitor experimental steps | Bisulfite conversion, staining, hybridization efficiency [22] |

Advanced Applications: Discordant Aging Patterns in Disease States

Recent research has revealed fascinating patterns of discordant tissue aging in disease states, particularly in cancer. A 2025 study analyzing epigenetic aging in women's cancers found that while cancer tissue itself shows accelerated epigenetic aging, some non-cancerous surrogate tissues from the same patients show decelerated aging patterns [8]. Specifically, in breast cancer patients, breast tissue exhibited higher epigenetic age compared to controls, but cervical samples showed lower epigenetic ages—a pattern that was validated in mouse models [8].

This finding has important methodological implications:

- Multi-tissue sampling provides a more complete picture of organismal aging than single-tissue assessments

- Surrogate tissues (like blood or cervical samples) may not always reflect aging processes in disease-affected organs

- Functionally enriched epigenetic clocks that focus on specific biological processes (senescence, proliferation, stem cell fate) may provide more interpretable results in disease contexts [8]

For researchers studying aging in disease contexts, we recommend:

- Collect multiple tissue types when possible, including diseased tissue, adjacent normal tissue, and easily accessible surrogate tissues

- Apply both conventional and functionally enriched clocks to capture different aspects of epigenetic dysregulation

- Interpret results cautiously when using surrogate tissues, recognizing they may not fully represent aging processes in target organs

The field of epigenetic clock research is rapidly evolving from blood-centric models to sophisticated multi-tissue applications. By adopting the troubleshooting approaches, standardized protocols, and algorithm selection frameworks outlined in this guide, researchers can significantly enhance the reliability and biological relevance of their epigenetic aging studies across diverse tissue types.

Future directions in the field include:

- Development of tissue-specific calibrated clocks that maintain cross-tissue comparability while optimizing accuracy for specific tissues

- Single-cell epigenetic clocks that will resolve cell-type-specific aging patterns within complex tissues

- Dynamic aging measures that can track aging trajectories over time rather than providing static assessments

- Functionally informed clocks that more directly link epigenetic changes to specific biological processes and functional outcomes

As these advances emerge, the principles of careful algorithm selection, methodological transparency, and biological validation outlined in this guide will remain essential for generating meaningful insights into the complex relationship between epigenetic aging and tissue function across health and disease states.

Sample Collection and Preservation Protocols for Multi-Tissue Studies

Troubleshooting Common Issues

FAQ: Why do my epigenetic age estimates vary dramatically between different tissues from the same donor?

This is a common finding due to tissue-specific epigenetic aging patterns. Research confirms that epigenetic clocks trained on blood-based tissues frequently show poor concordance when applied to other tissues. One study found average differences of almost 30 years between oral-based and blood-based tissues for some age clocks [6]. This occurs because each cell type has a unique DNA methylation signature, and tissues age at different rates within the same individual [6]. The solution is to use tissue-appropriate epigenetic clocks rather than applying blood-derived clocks to all tissue types.

FAQ: My RNA yield and quality are poor from archived tissue samples. What preservation factors should I review?

RNA is particularly labile and degrades rapidly if not properly preserved. Review these critical factors:

- Immediate stabilization: RNA degrades rapidly without immediate freezing or preservation [35].

- Preservation method: Most preservation methods used for DNA are not equally effective for RNA [35].

- Sample processing: Cut tissue into small pieces to allow permeation by preservative, but don't over-fill vials [35].