Mitigating Batch Effects in EWAS: A Comprehensive Guide from Study Design to Data Validation

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on addressing the critical challenge of batch effects in large-scale Epigenome-Wide Association Studies (EWAS).

Mitigating Batch Effects in EWAS: A Comprehensive Guide from Study Design to Data Validation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on addressing the critical challenge of batch effects in large-scale Epigenome-Wide Association Studies (EWAS). Covering foundational concepts to advanced applications, we detail how technical variation from sources like processing dates and microarray chips can confound biological signals and lead to false discoveries. The content explores robust methodological frameworks, including popular tools like ComBat and linear mixed models, while highlighting critical troubleshooting strategies for unbalanced study designs where batch correction can systematically introduce false positives. By integrating principles of thoughtful experimental design, careful data inspection, and rigorous validation, this guide equips professionals with the knowledge to produce reliable, reproducible epigenetic findings for drug development and clinical research.

Understanding Batch Effects: The Hidden Technical Confounders in EWAS

What are batch effects and why are they a critical concern in DNA methylation analysis?

Batch effects are systematic technical variations introduced into high-throughput data due to differences in experimental conditions rather than biological factors. These non-biological variations can arise from multiple sources throughout the experimental workflow, including differences in reagent lots, processing dates, personnel, instrumentation, and array positions [1] [2].

In DNA methylation studies, particularly those using Illumina Infinium BeadChip arrays (450K or EPIC), batch effects can profoundly impact data quality and interpretation. They inflate within-group variances, reduce statistical power to detect true biological signals, and potentially create false positive findings [1] [2]. In severe cases where batch effects are confounded with the biological variable of interest, they can lead to incorrect conclusions that misinterpret technical artifacts as biologically significant results [1] [3].

The consequences can be serious, including reduced experimental reproducibility, invalidated research findings, and in clinical contexts, potentially incorrect patient classifications affecting treatment decisions [1].

Batch effects can emerge at virtually every stage of a DNA methylation study. The table below summarizes the key sources and their impacts:

Table 1: Primary Sources of Batch Effects in DNA Methylation Studies

| Experimental Stage | Specific Sources | Impact on Data |

|---|---|---|

| Study Design | Unbalanced sample distribution across batches, confounded batch and biological variables [3] | Inability to separate technical from biological variance |

| Sample Processing | Bisulfite conversion efficiency [4] [2], DNA extraction methods [1], reagent lot variations [1] [2] | Systematic shifts in methylation measurements |

| Array Processing | Processing date [2], slide effects [2], row/position on array [2] [3], hybridisation conditions [2] | Position-specific technical artifacts |

| Instrumentation | Scanner variability [2], array manufacturing lots [2], ozone effects on dyes [2] | Intensity biases, particularly for specific probe types |

Different probe designs on methylation arrays also exhibit varying susceptibility to batch effects. Infinium I and II probes have different technical characteristics, with Infinium II probes showing reduced dynamic range and confounding of color channels with methylation measurement [2].

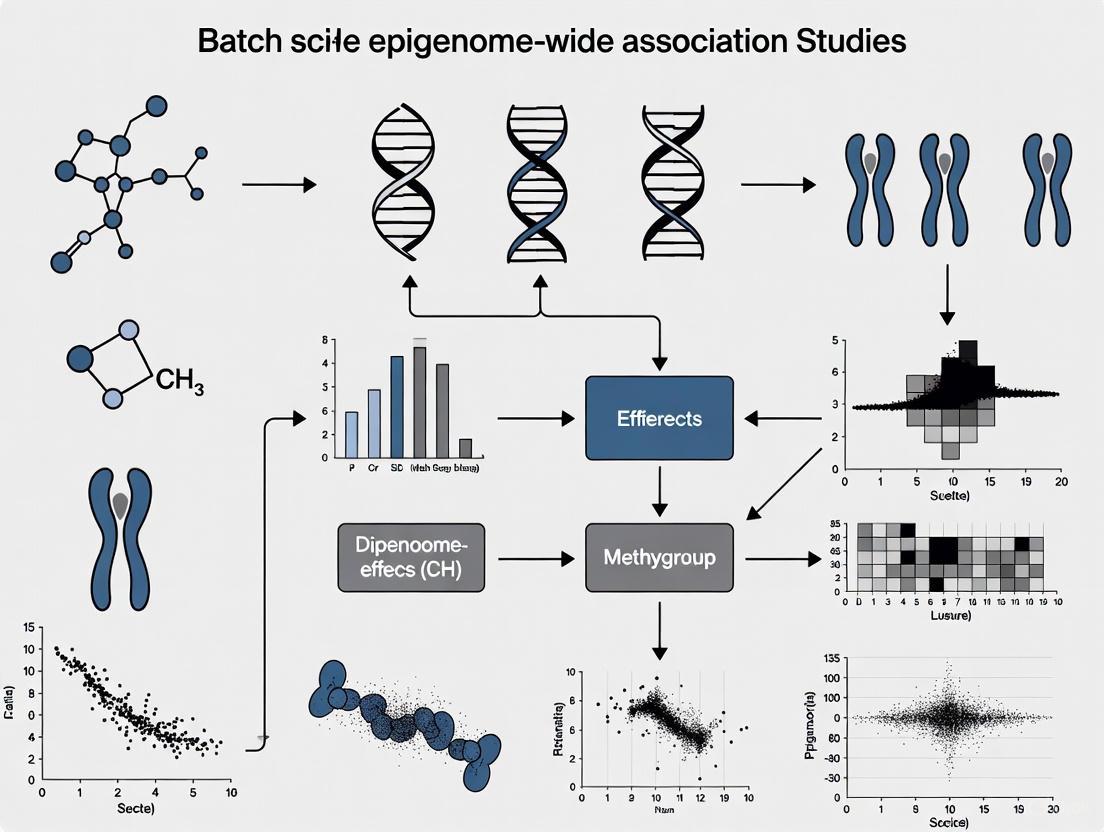

Figure 1: Sources of batch effects in DNA methylation studies

How can I detect and diagnose batch effects in my DNA methylation dataset?

Several diagnostic approaches can help identify batch effects before proceeding with formal analysis:

Principal Components Analysis (PCA) is a standard method for batch effect detection. By examining the top principal components and testing their association with both biological and technical variables, you can identify sources of unwanted variation [3]. For example, if principal components show strong association with processing date or array position rather than your biological variables of interest, this indicates significant batch effects [3].

Visualization methods include plotting sample relationships using dimensional scaling (MDS plots), examining intensity distributions across batches, and visualizing data before and after correction. These approaches help identify batch-driven clustering patterns that may mask true biological signals [2] [5].

Statistical testing for associations between technical variables and methylation values can quantify batch effect severity. Correlation analyses and variance partitioning can determine what proportion of data variation is attributable to batch factors versus biological factors [2].

Table 2: Batch Effect Detection Methods and Interpretation

| Method | Procedure | Interpretation of Batch Effects |

|---|---|---|

| PCA | Calculate principal components, test associations with technical variables [3] | Significant association of top PCs with technical variables (chip, row, processing date) indicates batch effects |

| MDS Plots | Plot samples in reduced dimensions based on methylation similarity | Clustering of samples by batch rather than biological group reveals batch effects |

| Distribution Analysis | Compare density plots of beta or M-values across batches | Systematic shifts in distribution centers or shapes between batches |

| Variance Partitioning | Quantify variance explained by batch vs. biological variables | High proportion of variance attributed to technical factors |

What are the main statistical methods for correcting batch effects in DNA methylation data?

Several computational approaches have been developed specifically for batch effect correction in DNA methylation data. The choice of method depends on your study design, data characteristics, and specific research questions.

Table 3: Batch Effect Correction Methods for DNA Methylation Data

| Method | Statistical Approach | Best Use Cases | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ComBat | Empirical Bayes framework with location/scale adjustment [6] [4] | Small sample sizes, balanced study designs [6] | Uses M-values; robust to small batches; can introduce false signals if confounded [3] |

| ComBat-met | Beta regression model accounting for [0,1] constraint of β-values [4] | Direct modeling of β-values without transformation | Specifically designed for methylation data characteristics |

| iComBat | Incremental framework based on ComBat [6] [7] | Longitudinal studies with sequentially added batches [6] | Corrects new data without reprocessing previous batches [6] |

| Reference-based Correction | Adjusts all batches to a designated reference batch [4] | Studies with a clear gold-standard or control batch | Requires careful reference selection |

| One-step Approach | Includes batch as covariate in differential analysis model [4] | Simple designs with minimal batch effects | Less effective for complex batch structures |

The standard ComBat method uses an empirical Bayes approach to adjust for both location (additive) and scale (multiplicative) batch effects [6]. It operates on M-values (log2 ratios of methylated to unmethylated intensities) rather than beta-values, as M-values have better statistical properties for linear modeling [2] [5].

For studies involving repeated measurements over time, the novel iComBat method provides an incremental framework that allows correction of newly added batches without modifying previously corrected data, making it particularly useful for longitudinal studies and clinical trials with ongoing data collection [6] [7].

Figure 2: Batch effect correction workflow for DNA methylation data

What are the potential pitfalls and limitations of batch effect correction methods?

While batch effect correction is essential, it must be applied carefully to avoid introducing new artifacts or removing genuine biological signals:

Over-correction occurs when batch effect removal algorithms mistakenly identify biological signal as technical noise and remove it. This is particularly problematic for biological variables with high population prevalence that are unevenly distributed across batches, such as cellular composition differences, gender-specific methylation patterns, or genotype-influenced methylation (allele-specific methylation) [2].

False discovery introduction can happen when applying correction methods like ComBat to severely unbalanced study designs where batch is completely confounded with biological groups. In such cases, correction may introduce thousands of false positive findings, as demonstrated in a 30-sample pilot study where application of ComBat to confounded data generated 9,612 significant differentially methylated positions despite none being present before correction [3].

Probe-specific issues affect certain CpG sites more than others. Some probes are particularly susceptible to batch effects, while others may be "erroneously corrected" when they shouldn't be adjusted [2]. Studies have identified 4,649 probes that consistently require high amounts of correction across datasets [2].

What is iComBat and how does it address challenges in longitudinal DNA methylation studies?

iComBat is an incremental batch effect correction framework specifically designed for studies involving repeated measurements of DNA methylation over time, such as clinical trials of anti-aging interventions [6] [8].

Traditional batch correction methods are designed to process all samples simultaneously. When new data are incrementally added to an existing dataset, correction of the new data affects previously corrected data, requiring complete reprocessing [6]. iComBat solves this problem by enabling correction of newly included batches without modifying already-corrected historical data [6] [7].

The method builds upon the standard ComBat approach, which uses a Bayesian hierarchical model with empirical Bayes estimation to borrow information across methylation sites within each batch, making it robust even with small sample sizes [6]. iComBat maintains this strength while adding the capability for sequential processing.

The iComBat methodology involves these key steps:

- Initial batch correction using standard ComBat for the first set of samples

- Parameter estimation for the hierarchical model

- Incremental correction of new batches using the established parameter distributions

- Consistent adjustment that maintains comparability with previously corrected data

This approach is particularly valuable for long-term clinical studies, longitudinal aging research, and any epigenome-wide association study (EWAS) with sequential data collection where maintaining consistent data processing across timepoints is essential for valid interpretation of results [6].

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

| Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Illumina Methylation Arrays | Genome-wide CpG methylation profiling | 450K or EPIC arrays for DNA methylation measurement [2] [5] |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits | Convert unmethylated cytosines to uracils | Critical sample preparation step; lot variations cause batch effects [4] [2] |

| Reference Standards | Control samples for cross-batch normalization | Quality control and reference-based correction [4] |

| ComBat Software | Empirical Bayes batch correction | General-purpose batch effect adjustment [6] [4] |

| ComBat-met | Beta regression for β-values | Methylation-specific data correction [4] |

| iComBat | Incremental batch correction | Longitudinal studies with sequential data [6] [7] |

| SeSAMe Pipeline | Preprocessing and normalization | Addresses technical biases before statistical correction [6] |

Epigenome-wide association studies (EWAS) using microarray platforms, such as the Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450K and EPIC arrays, are powerful tools for investigating genome-wide DNA methylation patterns. However, these studies are highly vulnerable to technical artifacts that can compromise data integrity and lead to spurious findings. Batch effects—systematic technical variations arising from factors like processing date, reagent lots, or personnel—represent a primary concern. When these technical variables are confounded with biological variables of interest, batch effects can be misinterpreted as biologically significant findings, dramatically increasing false discovery rates [9]. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers identify, mitigate, and correct for these vulnerabilities in their EWAS workflows.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Identifying and Diagnosing Batch Effects

Problem: Suspected batch effects are creating spurious associations or obscuring true biological signals in my methylation data.

Explanation: Batch effects are technical sources of variation that are not related to the underlying biology. They can arise from differences in sample processing times, different technicians, reagent lots, or distribution of samples across multiple chips [9] [10]. In one documented case, applying batch correction to an unbalanced study design incorrectly generated over 9,600 significant differentially methylated positions, despite none being present prior to correction [9].

Solution: Implement a systematic diagnostic workflow to detect and assess batch effects.

Table: Methods for Batch Effect Assessment

| Assessment Method | Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Principal Components Analysis (PCA) | Plot the first few principal components of the methylation data and color-code by potential batch variables (e.g., chip, row, processing date) [9] [10]. | Association of principal components with technical (not biological) variables indicates batch effects. |

| Unsupervised Hierarchical Clustering | Cluster all samples based on methylation profiles across all CpG sites [10]. | Samples clustering strongly by technical batch rather than biological group indicates severe batch effects. |

| Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) | Perform an ANOVA test for each CpG site with the batch variable as the predictor [10]. | A high proportion of CpGs significantly associated with batch (e.g., p < 0.01) indicates widespread technical bias. |

| Control Metric Evaluation | Evaluate 17 control metrics provided by the Illumina platform using dedicated control probes [11]. | Samples flagged by multiple control metrics may have poor performance due to technical failures. |

Experimental Protocol for Diagnosis:

- Define Batch Variables: Record all potential technical variables during your experiment, including BeadChip ID, processing date, bisulfite conversion batch, and technician.

- Perform PCA: Generate PCA plots using your normalized methylation data (M-values are often preferred for analysis). Test the top principal components for association with both biological and technical variables using statistical tests (e.g., Wilcoxon test) [9] [10].

- Validate with Clustering: Conduct unsupervised hierarchical clustering of all samples using a correlation-based distance matrix. Visually inspect if samples group primarily by technical batch.

- Quantify Impact: Run an ANOVA for each CpG site using the batch variable. Calculate the percentage of probes with a significant p-value (e.g., < 0.01) to gauge the severity [10].

Guide 2: Mitigating and Correcting Batch Effects

Problem: I have confirmed the presence of batch effects in my dataset. How can I remove them without introducing false signals?

Explanation: While thoughtful experimental design is the best antidote, batch effects in existing data require robust bioinformatic correction. Normalization can remove a portion of batch effects, but specialized methods are often needed for complete removal [10]. The choice of method is critical, as some approaches, like ComBat, can introduce false positives if applied to studies with an unbalanced design where the batch is completely confounded with the biological variable of interest [9].

Solution: A two-step procedure involving normalization followed by specialized batch-effect correction.

Table: Comparison of Batch Effect Correction Approaches

| Method | Mechanism | Best For | Cautions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study Design (Prevention) | Balancing the distribution of biological groups across all technical batches [9]. | All new studies. | The most effective solution; must be planned before data generation. |

| Quantile Normalization | Adjusts the distribution of probe intensities across samples to be statistically similar. Can be applied to β-values or signal intensities [10]. | Initial reduction of technical variation. | Alone, it may be insufficient for severe batch effects [10]. |

| Empirical Bayes (ComBat) | Uses an empirical Bayes framework to adjust for batch effects by pooling information across genes and samples [9] [10]. | Small sample sizes and complex batch structures. | Can introduce false signal if study design is unbalanced/confounded [9]. |

| Linear Mixed Models | Incorporates batch as a random effect in the statistical model during differential methylation testing. | Balanced designs and when batch is not confounded with the variable of interest. | Computationally intensive for very large datasets. |

Experimental Protocol for Correction:

- Prioritize Balanced Design: For future studies, ensure samples from different biological groups are randomly and evenly distributed across chips, rows, and processing batches [9].

- Apply Normalization: Choose and apply a normalization method (e.g., quantile normalization on signal intensities as in the "lumi" package) to reduce technical variation between samples [10].

- Assess Residual Batch Effects: Re-run the diagnostic steps from Guide 1 to see if normalization alone was sufficient.

- Apply Batch Correction: If significant batch effects remain, apply a method like ComBat. Crucially, only do this if your design is not confounded. If batches are completely confounded with groups, correction is statistically inadvisable, and the data may be unusable [9].

- Validate Correction: After correction, repeat PCA and clustering to confirm the removal of batch-associated clustering. Use positive controls (e.g., technical replicates, known biological differences) to ensure biological signals were not distorted.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: My study design is confounded—all my cases were run on one chip and all controls on another. What can I do with my data?

A: This is a severe limitation. Applying batch-effect correction methods like ComBat to a completely confounded design is dangerous, as it can create false biological signal [9]. Your options are limited:

- Acknowledge the Confounding: In any publication, clearly state that the batch is completely confounded with the phenotype and that the results may be technically driven.

- Seek Validation: The most robust approach is to validate any findings in an independently collected and processed cohort with a balanced design.

- Exploratory Analysis Only: Consider the analysis purely exploratory and do not make strong biological conclusions from it.

Q: Beyond batch effects, what other sample quality issues should I check for?

A: Batch effects are just one of several technical pitfalls. A comprehensive quality control workflow should also include:

- Sex Check: Compare the recorded sex of sample donors with the methylation-based sex prediction (from X and Y chromosome probes) to identify mislabeling [11].

- Sample Contamination: Use the 65 SNP probes on the array to check for sample contamination or cross-contamination. Outliers in the genotype clusters can indicate contaminated samples [11].

- Detection P-values: Filter out probes with high detection p-values (poor signal-to-noise ratio). Improved filtering methods that use background fluorescence can more accurately mark unreliable probes, such as Y-chromosome probes in female samples [12].

Q: Should I use Beta-values or M-values for my statistical analysis?

A: Both metrics have their place. Beta-values are more biologically intuitive (representing a proportion between 0 and 1) and are preferable for data visualization and reporting. However, M-values (the log2 ratio of methylated to unmethylated intensities) have better statistical properties for differential analysis because they are more homoscedastic and perform better in hypothesis testing [5]. A standard practice is to use M-values for the statistical identification of differentially methylated positions and then report the corresponding Beta-values for interpretation.

Q: What is the recommended software pipeline for analyzing 450K or EPIC array data?

A: Two of the most widely used and comprehensive packages in R are Minfi and ChAMP [13]. Both can import raw data, perform quality control, normalization, and probe-wise differential methylation analysis. Minfi is historically the most cited for 450K data, while ChAMP is gaining popularity for EPIC data analysis. These open-source packages have largely replaced Illumina's proprietary GenomeStudio for analysis [13].

Table: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item / Resource | Function / Purpose | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Illumina Infinium BeadChip | The microarray platform (450K/EPIC) for genome-wide methylation profiling. | The EPIC array covers more CpG sites in enhancer regions but is processed similarly to the 450K [5]. |

| Bisulfite Conversion Reagents | Chemically converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils, enabling methylation detection. | The purity of input DNA is critical for efficient conversion; particulate matter can hinder the process [14]. |

| Minfi R Package | A comprehensive bioinformatics pipeline for importing, QC-ing, and analyzing methylation array data [13]. | The most cited tool for 450K data analysis; integrates well with other Bioconductor packages. |

| ChAMP R Package | An alternative all-in-one analysis pipeline for methylation data, including DMP and DMR detection [13]. | Becoming the most cited tool for EPIC data analysis; offers a streamlined workflow. |

| ComBat Software | An empirical Bayes method implemented in R to adjust for batch effects in high-dimensional data [9] [10]. | Use with caution; can introduce false discoveries in unbalanced study designs [9]. |

| EWATools R Package | A package dedicated to advanced quality control, including detecting mislabeled, contaminated, or poor-quality samples [12] [11]. | Essential for checks beyond standard metrics, such as sex mismatches and sample fingerprinting. |

Within the framework of a broader thesis on mitigating batch effects in large-scale epigenome-wide association studies (EWAS), this technical support center addresses the critical consequences of uncontrolled batch effects. Batch effects, defined as systematic technical variations introduced during experimental processing unrelated to biological variation, represent a paramount challenge in high-throughput genomic research [1]. In EWAS, where detecting subtle epigenetic changes is crucial, failure to adequately control for batch effects can lead to false discoveries, spurious associations, and ultimately reduced reproducibility of findings [15] [2]. This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with practical troubleshooting guidance and frequently asked questions to identify, address, and prevent the detrimental impacts of batch effects in their epigenomics research.

Understanding Batch Effects and Their Impacts: FAQs

What are batch effects and how do they arise in EWAS?

Batch effects are systematic technical variations that occur when samples are processed and measured in different batches, introducing non-biological variance that can confound results [16]. In epigenome-wide association studies utilizing Illumina Infinium Methylation BeadChip arrays, batch effects commonly arise from:

- Processing variables: Differences in processing dates, reagent lots, personnel, and specific slide positions [2]

- Technical artifacts: Variations in bisulfite conversion efficiency, hybridization conditions, scanner variability, and fluorophore degradation [2]

- Sample handling: Differences in sample collection, storage conditions, and nucleic acid isolation techniques [1]

- Study design factors: Confounded designs where biological variables of interest correlate with batch variables [16]

How can uncontrolled batch effects lead to false discoveries?

Uncontrolled batch effects produce two primary types of erroneous conclusions in EWAS research:

False positive findings: Batch effects can create spurious signals that are misinterpreted as biologically significant associations [16] [1]. This occurs particularly when batch variables correlate with outcome variables of interest.

False negative findings: Technical variation from batch effects can obscure genuine biological signals, reducing statistical power and preventing detection of true associations [16] [1].

The following workflow illustrates how batch effects propagate through a typical EWAS analysis, leading to erroneous conclusions:

What are real-world examples of severe consequences from batch effects?

Substantial evidence demonstrates the profound negative impacts of uncontrolled batch effects in genomic research:

Clinical trial misinterpretation: In one clinical study, a change in RNA-extraction solution introduced batch effects that resulted in incorrect gene-based risk calculations for 162 patients, 28 of whom received incorrect or unnecessary chemotherapy regimens [1].

Species misinterpretation: Initial research suggested cross-species differences between human and mouse were greater than cross-tissue differences within species. However, this was later attributed to batch effects from different experimental designs and data generation timepoints. After proper batch correction, data clustered by tissue type rather than species [1].

Retracted publications: High-profile articles have been retracted due to batch-effect-driven irreproducibility. In one case, the sensitivity of a fluorescent serotonin biosensor was found to be highly dependent on reagent batch (particularly fetal bovine serum), making key results unreproducible when batches changed [1].

Multi-omics challenges: Batch effects are particularly problematic in multi-omics studies where different data types have different distributions and scales, creating complex batch effect structures that are difficult to correct [1].

How do I determine if my data has problematic batch effects?

Several diagnostic approaches can identify batch effects in EWAS data:

Visualization Methods:

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Plot samples colored by batch; separation along principal components indicates batch effects [17] [18]

- t-SNE/UMAP visualization: Clustering of samples by batch rather than biological factors suggests batch effects [17] [18]

- Heatmaps and dendrograms: Samples clustering by batch rather than treatment group indicate batch effects [18]

Quantitative Metrics:

- Normalized Mutual Information (NMI)

- Adjusted Rand Index (ARI)

- k-nearest neighbor batch effect test (kBET) [17]

- Graph-based integrated local similarity inference (Graph_ILSI) [17]

The following diagnostic workflow illustrates a systematic approach to batch effect detection:

Quantitative Impacts of Batch Effects

Documented cases of batch effect consequences in genomic studies

Table 1: Documented Impacts of Batch Effects in Large-Scale Genomic Studies

| Study/Context | Batch Effect Source | Impact Description | Quantitative Measure |

|---|---|---|---|

| gnomAD exome vs. genome comparison [19] | Alignment differences (BWA vs. Dragmap) | Discordant variant calls between exome and genome data | 856 significant discordant SNP hits (Q34 quality score) reduced to 68 after filtering |

| TOPMed cross-batch analysis [19] | Different sequencing centers | False positive variants in cross-batch case-control analysis | 347 significant hits with VQSR filters alone (Q38); reduced to 54 with additional filters |

| Clinical trial risk calculation [1] | RNA-extraction solution change | Incorrect patient classification | 162 patients affected (28 received incorrect chemotherapy) |

| Methylation array analysis [2] | Processing day, slide position | Residual batch effects after standard preprocessing | 4,649 probes consistently requiring high correction across 2,308 samples |

Statistical impacts of batch effects on analytical outcomes

Table 2: Statistical Consequences of Uncorrected Batch Effects

| Impact Category | Effect on Analysis | Downstream Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| Type I Error Inflation | Increased false positive rates | Spurious associations reported as significant; misleading biological conclusions |

| Type II Error Increase | Reduced statistical power | Genuine biological signals obscured; failure to detect true associations |

| Effect Size Bias | Over- or under-estimation of true effects | Exaggerated or diminished biological importance; incorrect interpretation |

| Data Integration Challenges | Inability to combine datasets | Reduced sample size and power; limitations in meta-analysis |

Experimental Protocols for Batch Effect Characterization

Protocol 1: Systematic batch effect detection in methylation array data

Purpose: Identify and quantify batch effects in Illumina Infinium 450K or EPIC array data.

Materials:

- Raw methylation β-values or M-values

- Sample batch annotation (processing date, slide, position)

- Biological covariates (age, sex, cell type proportions)

Methodology:

- Data Preparation: Convert β-values to M-values for statistical stability [2]

- Initial Visualization: Perform PCA colored by batch and biological variables

- Variance Partitioning: Use linear models to quantify variance attributable to batch vs. biological factors

- Probe-Level Assessment: Identify probes with excessive batch sensitivity using ComBat or Harman [2]

- Batch Effect Metric Calculation: Compute intra-class correlation (ICC) for batches

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If biological variables are confounded with batch, consider causal methods [16]

- For small sample sizes, use empirical Bayes approaches for more stable estimation [20]

- Always validate findings with multiple visualization approaches

Protocol 2: Assessing correction efficacy and overcorrection risks

Purpose: Evaluate batch effect correction performance while avoiding overcorrection.

Materials:

- Batch-corrected and uncorrected data

- Known biological control markers (e.g., X-chromosome inactivation genes in females)

- Cell type-specific methylation signatures

Methodology:

- Post-Correction Visualization: Compare PCA/UMAP plots before and after correction

- Biological Signal Preservation: Assess whether known biological differences persist after correction

- Overcorrection Detection: Check for these signs of overcorrection [17] [18]:

- Distinct cell types clustering together

- Loss of expected cluster-specific markers

- Significant overlap among markers specific to different clusters

- Ribosomal genes appearing as top cluster markers

- Quantitative Metrics: Calculate integration metrics (ARI, NMI) to assess correction quality

Interpretation Guidelines:

- Successful correction: Batch separation reduced while biological separation maintained

- Under-correction: Batch-specific clustering still evident

- Overcorrection: Biological patterns lost or distorted

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Batch Effect Management in EWAS

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Methods | Function/Purpose | Considerations for EWAS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Tools | PCA, UMAP, t-SNE [17] [18] | Visual identification of batch effects | Use M-values rather than β-values for better statistical properties [2] |

| Statistical Tests | kBET, ARI, NMI [17] | Quantitative batch effect assessment | Provides objective measures for effect size |

| Correction Algorithms | ComBat, Harman [2] | Remove technical variation while preserving biological signals | ComBat performs better with known batch designs; requires careful parameterization [20] |

| Causal Methods | Causal cDcorr, Matching cComBat [16] | Address confounding between biological and technical variables | Particularly valuable when biological and batch variables are correlated |

| Reference Materials | Control probes, sample replicates | Monitor technical performance across batches | Include across all batches to track technical variance |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines | sva, limma, Seurat [21] [22] | Implement standardized correction workflows | Choose based on data type (count vs. continuous) and study design |

| Agaritine | Agaritine, CAS:2757-90-6, MF:C12H17N3O4, MW:267.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Alclofenac sodium | Alclofenac sodium, CAS:24049-18-1, MF:C11H10ClNaO3, MW:248.64 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Advanced Considerations in Batch Effect Management

The challenge of unbalanced designs and two-step correction

In EWAS research, unbalanced group-batch designs (where biological groups are unevenly distributed across batches) present particular challenges for batch effect correction:

Key Issue: Standard two-step correction methods (like ComBat) introduce correlation structures in the corrected data that can lead to either exaggerated or diminished significance in downstream analyses [20].

Solutions:

- Design-aware correction: Use methods that explicitly account for group-batch imbalance

- Correlation adjustment: Implement ComBat+Cor approach that estimates and adjusts for the induced sample correlation [20]

- One-step methods: Include batch directly in differential analysis models rather than pre-correcting data

Causal perspectives on batch effects

Recent advances in batch effect management incorporate causal inference frameworks:

Conceptual Shift: Traditional methods treat batch effects as associational or conditional effects, while causal approaches model them as causal effects [16].

Benefits:

- Better handling of scenarios where biological and technical variables are confounded

- Ability to acknowledge when data are insufficient to confidently conclude about batch effects

- More appropriate correction that avoids removing biological signal

Implementation: Causal methods like Matching cComBat can be applied to existing correction workflows to improve performance when covariate overlap is limited [16].

Integrated Batch Effect Management Workflow

The following comprehensive workflow integrates detection, correction, and validation for robust batch effect management in EWAS:

This structured approach to batch effect management ensures that EWAS researchers can minimize false discoveries and spurious associations while maintaining the biological integrity of their findings. Through vigilant detection, appropriate correction, and rigorous validation, the research community can enhance the reproducibility and reliability of epigenome-wide association studies.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Batch Effect Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: What are the most common sources of batch effects in EWAS? Batch effects are systematic technical variations unrelated to your study's biology. The common sources you must account for include:

- Processing Date: The day samples are processed or run on the array/sequencer is a major source of variation, as differences in ambient conditions, ozone levels, and operator focus can affect results [2].

- Reagent Batch Variation: Lot-to-lot differences in reagents, such as bisulfite conversion kits, buffers, and staining solutions, are a frequent cause of batch effects [1] [23]. A prominent example shows that changing the batch of fetal bovine serum (FBS) led to the retraction of a high-profile study when key results became irreproducible [1].

- Chip/Slide and Row/Position: For Illumina BeadChip arrays, the specific glass slide (each containing 8 or 12 arrays) and the physical position of the array on that slide introduce variability. This can be due to differences in hybridisation conditions or scanning artifacts across the slide [2].

FAQ 2: How can I detect batch effects in my methylation data? A multi-faceted approach is recommended for detecting batch effects:

- Principal Components Analysis (PCA): Visualize your data using a PCA plot. If samples cluster strongly by batch (e.g., processing date or slide) rather than by biological group, you have a clear indicator of batch effects [24] [2].

- k-Nearest Neighbor Batch Effect Test (kBET): This quantitative method measures how well batches are mixed at the local level for every sample, providing a robust statistical test for batch effect presence [24].

FAQ 3: My biological groups are completely confounded with batch (e.g., all cases were processed in one batch, all controls in another). What can I do? This is a severely confounded scenario where standard correction methods fail because they cannot distinguish technical variation from biological signal [23]. The most effective solution is a proactive experimental design:

- Use Reference Materials: Process a common reference material (e.g., a commercial or lab-standard control sample) in every batch. You can then use a ratio-based method to scale the feature values of your study samples relative to the reference material, effectively canceling out the batch-specific technical variation [23].

- Randomization: Always randomize the sequencing order of samples from different biological groups across your batches to avoid confounding [25].

FAQ 4: Which batch effect correction method should I use for my data? The choice of method depends on your data structure and the level of confounding. The table below summarizes the performance of various algorithms based on recent large-scale benchmarks.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Common Batch Effect Correction Algorithms

| Algorithm | Primary Approach | Best For | Key Strengths | Noted Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ComBat [15] [6] | Empirical Bayes / Linear Model | Bulk DNA methylation data (EWAS) [15]. | Robust even with small sample sizes per batch [6]. | Can be outperformed by newer methods in complex, confounded scenarios [23]. |

| Harmony [23] [26] | Mixture Model / Iterative PCA | Integrating diverse datasets and single-cell data. | Consistently high performer across multiple data types and benchmarks [26]. | Requires the entire dataset for correction; not suitable for incremental data [6]. |

| Ratio-Based (e.g., Ratio-G) [23] | Scaling to Reference Material | Confounded designs and large-scale multi-omics studies. | Effectively corrects data even when biology is completely confounded with batch [23]. | Requires planned inclusion of a reference material in every batch. |

| iComBat [6] | Incremental Empirical Bayes | Longitudinal studies with new data added over time. | Corrects new batches without altering or requiring the reprocessing of previously corrected data [6]. | A newer method, based on the established ComBat framework. |

FAQ 5: Are there specific probes on methylation arrays that are more prone to batch effects? Yes. Despite normalization, some probes on Illumina Infinium BeadChips are persistently susceptible to batch effects. One analysis of over 2,300 arrays identified 4,649 probes that consistently required high amounts of correction across multiple datasets [2]. It is crucial to be aware that these probes have sometimes been erroneously reported as key sites of differential methylation in published studies [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Separation of Biological Groups After Data Integration

Problem: After merging and correcting data from multiple batches (chips, runs), your biological groups of interest (e.g., case vs. control) do not separate well in analysis.

Solution:

- Diagnose Confounding: Check your experimental design. If your biological groups are perfectly aligned with batches (e.g., all cases on one chip, all controls on another), standard correction methods will fail [23].

- Apply a Ratio-Based Correction: If you have included a reference material in each batch, use a ratio-based method (see Table 1) to correct your data. This is the most reliable approach for confounded designs [23].

- Re-evaluate Method Choice: If you did not use a reference material, try a different correction algorithm. Benchmarks show that Harmony and ratio-based methods often perform well in complex scenarios [23] [26].

Issue 2: Introducing False Positives or Removing Biological Signal

Problem: After batch effect correction, you suspect that real biological signals have been removed or that new artificial signals have been created.

Solution:

- Use M-Values for Correction: Always perform batch effect correction on M-values rather than Beta-values. M-values are unbounded and statistically more robust for these operations. You can transform the corrected M-values back to Beta-values for interpretation [2].

- Identify Problematic Probes: Be aware that batch correction tools can erroneously "correct" probes that are influenced by underlying biological factors like genotype or metastable epialleles [2]. Consult published lists of batch-effect-prone and erroneously corrected probes to filter your dataset [2].

- Visualize Post-Correction: Always run PCA and other diagnostics on your data after correction to ensure batch effects are reduced without distorting the biological reality.

Experimental Protocols for Batch Effect Mitigation

Protocol 1: Proactive Study Design to Minimize Batch Effects

A well-designed experiment is the first and most important step in controlling batch effects [1].

- Randomization: Randomly assign samples from all biological groups across all your batches (chips, processing dates) [25].

- Include Reference Materials: Plan to include one or more technical replicate(s) of a reference material (e.g., a commercial standard or a pooled sample) in every processing batch [23].

- Balance Batches: Ensure each batch contains a similar proportion of samples from each biological condition and any key covariates (e.g., age, sex) [1].

- Metadata Tracking: Meticulously record all technical metadata, including processing date, chip ID, row/position, and reagent lot numbers [25] [2].

Protocol 2: A Workflow for Batch Effect Detection and Correction in EWAS

This workflow outlines the key steps for handling batch effects in DNA methylation array data, from processing to analysis.

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for detecting and correcting batch effects:

Detailed Steps:

- Raw Data & Preprocessing: Begin with raw intensity files and apply standard preprocessing (background correction, dye-bias correction, normalization) specific to your platform (e.g., Illumina 450K/EPIC) [2].

- Initial PCA: Perform PCA on the preprocessed data (using M-values is recommended) and color the plot by known batch variables (processing date, chip) and biological groups. This visualizes the extent of batch effects before correction [2].

- Choose & Apply Correction: Based on your study design (see Table 1), select an appropriate batch effect correction algorithm (e.g., ComBat, Harmony). For confounded designs, a ratio-based method is mandatory [23].

- Post-Correction Diagnostics: Run PCA again on the corrected data. Successful correction is indicated by the mixing of batches, while biological groups should become the primary source of variation.

- Biological Validation: Ensure that known biological truths (e.g., strong differences between tissue types, or expected X-chromosome methylation in females) are preserved after correction [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key materials and their functions essential for designing robust EWAS that mitigate batch effects.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Batch Effect Control

| Item | Function in Mitigating Batch Effects |

|---|---|

| Reference Materials (e.g., commercially available methylated DNA controls or lab-generated pooled samples) | Served as a technical baseline across all batches. Enables the use of ratio-based correction methods, which are powerful for confounded study designs [23]. |

| Multi-Channel Pipettes or Automated Liquid Handlers | Reduces well-to-well variation during sample and reagent loading onto BeadChips, minimizing positional (row) effects within a slide [2]. |

| Single-Lot Reagents | Using the same lot of all critical reagents (bisulfite conversion kits, enzymes, buffers) for an entire study eliminates variation from reagent batches [1]. |

| Ozone Scavengers | Protects fluorescent dyes (especially Cy5) from degradation by ambient ozone, which can vary by day and lab environment, thus reducing a key source of technical noise [2]. |

| 10-Formylfolic acid | 10-Formylfolic Acid |Potent DHFR Inhibitor |

| 10-Propoxydecanoic acid | 10-Propoxydecanoic acid, CAS:119290-00-5, MF:C13H26O3, MW:230.34 g/mol |

Batch Effect Correction Strategies: From ComBat to Linear Mixed Models

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the most common sources of batch effects in DNA methylation studies? Batch effects in DNA methylation data arise from systematic technical variations, including differences in bisulfite conversion efficiency, processing date, reagent lots, individual glass slides, array position on the slide, DNA input quality, and enzymatic reaction conditions. These technical artifacts can profoundly impact data quality and lead to both false positive and false negative results in downstream analyses [4] [2].

Should I use Beta-values or M-values for batch effect correction? For statistical correction methods, you should use M-values for the actual batch correction process. M-values are unbounded (log2 ratio of methylated to unmethylated intensities), making them more statistically valid for linear modeling and batch adjustment. After correction, you can transform the data back to the more biologically intuitive Beta-values (ranging from 0-1, representing methylation percentage) for visualization and interpretation [5] [2] [3].

Can batch effect correction methods create false positives? Yes, particularly when applied to unbalanced study designs where biological groups are confounded with batch. There are documented cases where applying ComBat to confounded designs dramatically increased the number of supposedly significant methylation sites, introducing false biological signal. The optimal solution is proper experimental design that distributes biological groups evenly across batches [3].

Which probes are most problematic for batch effect correction? Research has identified that approximately 4,649 probes consistently require high amounts of correction across diverse datasets. These batch-effect prone probes, along with another set of probes that are erroneously corrected, can distort biological signals. It's recommended to consult reference matrices of these problematic features when analyzing Infinium Methylation data [2].

What are the key differences between ComBat and ComBat-met? ComBat uses an empirical Bayes framework assuming normally distributed data and is widely used for microarray data. ComBat-met employs a specialized beta regression framework that accounts for the unique distributional characteristics of DNA methylation Beta-values (bounded between 0-1, often skewed or over-dispersed), making it more appropriate for methylation data [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Batch Effect Removal After Standard Correction

Symptoms: Principal Component Analysis (PCA) still shows strong clustering by batch rather than biological group after correction; high technical variation persists in quality control metrics.

Solutions:

- Verify data preprocessing: Ensure proper normalization has been applied before batch correction. For Illumina arrays, methods like quantile normalization, functional normalization, or Noob normalization should be implemented first [5] [27].

- Switch to specialized methods: Use ComBat-met instead of standard ComBat for better performance with Beta-value distributions [4].

- Increase model specificity: Include multiple batch variables in your correction model (e.g., processing date, slide, row position) rather than a single batch factor [3].

- Filter problematic probes: Remove the known batch-effect prone probes (approximately 4,649 identified in multiple studies) before conducting differential methylation analysis [2].

Verification Check:

- Re-run PCA after correction - batch clusters should be diminished while biological signals remain

- Check association between principal components and batch variables - p-values should be >0.05 after successful correction

Problem: Excessive False Positives After Batch Correction

Symptoms: Dramatic increase in significant differentially methylated positions after correction; results that don't align with biological expectations.

Solutions:

- Check study design balance: Ensure biological groups are evenly distributed across batches. If completely confounded, batch correction may introduce false signals [3].

- Use reference-based correction: For ComBat-met, adjust all batches to a designated reference batch rather than the common mean, which can provide more stable results [4].

- Apply parameter shrinkage: Utilize empirical Bayes shrinkage in ComBat or ComBat-met to borrow information across features and prevent overcorrection [4].

- Validate with negative controls: Include control samples or regions where no biological differences are expected to monitor false discovery rates.

Critical Pre-Correction Checklist:

- Biological groups balanced across batches

- M-values used for correction, not Beta-values

- Known biological covariates (sex, age, cell composition) included in model

- Sufficient sample size per batch (>3-5 samples recommended)

Problem: Inconsistent Results Across Different Methylation Platforms

Symptoms: Different statistical significance patterns when analyzing the same biological conditions on 450K vs. EPIC arrays, or between array and sequencing-based data.

Solutions:

- Platform-aware normalization: Account for different probe types (Infinium I vs. II) that have different technical characteristics and dynamic ranges [5] [2].

- Common CpG filtering: Analyze only the overlapping CpG sites between platforms when comparing results.

- Method adjustment: For sequencing-based data (WGBS, RRBS), use methods like DSS or dmrseq that are specifically designed for count-based methylation data rather than array-based correction tools [28].

- Batch correction before integration: Correct batch effects within each platform separately before integrating datasets.

Comparison of Batch Effect Correction Methods

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of DNA Methylation Batch Correction Methods

| Method | Underlying Model | Best For | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ComBat-met | Beta regression | Methylation β-values | Models bounded nature of β-values; improved statistical power | Newer method, less established in community [4] |

| ComBat | Empirical Bayes (Gaussian) | M-values | Established method; handles small sample sizes | Assumes normality, inappropriate for β-values [4] [3] |

| Naïve ComBat | Empirical Bayes (Gaussian) | (Not recommended) | Simple implementation | Inappropriate for β-values, poor performance [4] |

| One-step Approach | Linear model with batch covariate | Balanced designs | Simple, maintains data structure | Limited for complex batch effects [4] |

| SVA | Surrogate variable analysis | Latent batch effects | Does not require known batch structure | Risk of removing biological signal [4] |

| RUVm | Remove unwanted variation | With control features | Uses control probes/features for guidance | Requires appropriate control features [4] |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison Based on Simulation Studies

| Method | True Positive Rate | False Positive Rate | Handling of Severe Batch Effects | Differential Methylation Recovery |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ComBat-met | Superior | Correctly controlled | Effective | Improved statistical power [4] |

| M-value ComBat | Moderate | Generally controlled | Effective in some cases | Good, but may miss some true effects [4] [27] |

| One-step Approach | Lower | Controlled | Limited | Reduced power for subtle effects [4] |

| SVA | Variable | Generally controlled | Depends on surrogate variable identification | Inconsistent across datasets [4] |

| No Correction | Low (effects masked) | Variable | Poor | Severely compromised [4] [27] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: ComBat-met Implementation for Methylation Arrays

Principle: ComBat-met uses a beta regression framework to model methylation β-values, calculates batch-free distributions, and maps quantiles to adjust data while respecting the bounded nature of methylation data [4].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

Data Preparation

- Load β-values from processed methylation data (minfi, sesame, or other preprocessing pipelines)

- Retain probe and sample filtering information

- Define batch variables (slide, processing date, position)

- Prepare biological covariates of interest

Model Fitting

Parameters are estimated via maximum likelihood using beta regression [4]

Batch-free Distribution Calculation

- Calculate common cross-batch average:

- μ'i = (∑j nj × μij) / (∑j nj)

- φ'i = (∑j nj × φij) / (∑j nj)

- For reference-based adjustment: use reference batch parameters

- Calculate common cross-batch average:

Quantile Matching Adjustment

- For each observation, find its quantile in the estimated batch-specific distribution

- Map to the same quantile in the batch-free distribution

- Output adjusted β-values bounded between 0-1

Validation Steps:

- PCA visualization before/after correction

- Correlation analysis with batch variables

- Differential methylation analysis with positive/negative controls

Protocol 2: Comprehensive Batch Effect Detection and Diagnosis

Purpose: Identify potential batch effects before committing to a specific correction approach.

Implementation:

Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

- Perform PCA on M-values

- Test association between top PCs (typically 6-10) and both technical and biological variables

- Use ANOVA for categorical variables, correlation for continuous variables

Technical Variable Assessment Table 3: Key Technical Variables to Assess for Batch Effects

Variable Assessment Method Significance Threshold Processing date PCA correlation p < 0.05 Slide/chip PCA ANOVA p < 0.01 Row position PCA correlation p < 0.05 Column position PCA correlation p < 0.05 Bisulfite conversion batch PCA ANOVA p < 0.05 Sample plate PCA ANOVA p < 0.05 Control Probe Analysis

- Examine intensity values of control probes across batches

- Check bisulfite conversion efficiency controls

- Monitor hybridization controls for degradation

Interpretation: Significant associations between principal components and technical variables indicate batch effects requiring correction. If biological variables of interest are confounded with these technical variables, exercise caution in interpretation [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for DNA Methylation Batch Correction

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| ComBat-met | Beta regression-based batch correction | Specifically designed for DNA methylation β-values [4] |

| sva package | Surrogate variable analysis | Latent batch effect detection and adjustment [4] |

| missMethyl package | Normalization and analysis of methylation data | Array-specific preprocessing and normalization [5] |

| DSS package | Differential methylation for sequencing | WGBS and RRBS data analysis [28] |

| bsseq package | Analysis of bisulfite sequencing data | WGBS/RRBS data management and basic analysis [28] |

| minfi package | Preprocessing of methylation arrays | 450K/EPIC array data preprocessing and quality control [5] |

| IlluminaHumanMethylation450kanno.ilmn12.hg19 | Annotation for 450K arrays | Probe annotation and genomic context [5] |

| Reference matrices of problematic probes | Filtering batch-effect prone probes | Identification of 4,649 consistently problematic probes [2] |

| 10-Thiofolic acid | 10-Thiofolic acid, CAS:54931-98-5, MF:C19H18N6O6S, MW:458.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2-Methoxycinnamic acid | 2-Methoxycinnamic acid, CAS:1011-54-7, MF:C10H10O3, MW:178.18 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Workflow Diagrams

Batch Effect Correction Decision Workflow

ComBat-met Methodology Workflow

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the correct way to specify the model matrix (mod argument) in ComBat to preserve my biological variables of interest?

The mod argument should be a design matrix for the variables you wish to preserve in your data, not the ones you want to remove. The batch variable itself is specified separately in the batch argument. For example, if your variables of interest are treatment, sex, and age, and you have known confounders like RNA integrity index, the mod matrix should be constructed to include all these variables you want to protect from being harmonized away [29].

Q2: When should I use ComBat versus other batch effect correction methods like limma's removeBatchEffect?

The choice depends on your data type and analysis goals:

- ComBat is particularly useful for small sample sizes because its Empirical Bayes framework borrows information across genes to improve batch effect estimation [22].

ComBat-seqis a specific variant designed for raw RNA-seq count data [22]. removeBatchEffectfrom thelimmapackage is well-integrated into thelimma-voomworkflow but operates on normalized, log-transformed data. Note that its output is not intended for direct use in differential expression tests; instead, include batch in your linear model during differential analysis [22].- For more complex experimental designs with nested or hierarchical batch effects, Mixed Linear Models (MLM) can be a powerful alternative [22].

Q3: My data includes a strong biological covariate that is unbalanced across batches. Can ComBat handle this?

Yes, but this is a critical situation that requires careful specification of the mod matrix. If the biological covariate (e.g., disease stage) is not included in mod, ComBat may mistakenly interpret the biological difference as a batch effect and remove it, potentially harming your analysis [30]. Always include such biological covariates in the mod matrix to protect them during harmonization [30].

Q4: How can I validate that ComBat harmonization was successful?

A primary method is visual inspection using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [22].

- Before Correction: The PCA plot typically shows samples clustering primarily by their batch.

- After Successful Correction: The batch-specific clustering should be reduced or eliminated, and samples should group based on biological conditions.

Statistical tests like the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test can also be used to check if the distributions of feature values from different batches are significantly different before harmonization and aligned afterwards [30].

Common Error Messages and Solutions

| Error Message / Problem | Likely Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Convergence issues or poor correction with small batch sizes (n < 10). | The Empirical Bayes estimation requires sufficient data per batch to reliably estimate parameters [30]. | Consider using the "frequentist" ComBat option (empiricalBayes = FALSE) or evaluate if batches can be logically grouped. Ensure the model matrix is correctly specified [29]. |

| Biological signal appears weakened after ComBat. | The biological variable of interest was not included in the mod matrix and was incorrectly adjusted for [30]. |

Re-run ComBat, ensuring all crucial biological covariates and known confounders to be preserved are in the mod design matrix [29]. |

| Post-harmonization, distributions are aligned, but mean/SD values seem arbitrary. | ComBat by default aligns batches to an overall "virtual" reference. | Use ComBat's ref.batch argument to specify a particular batch as the reference, which can aid in the interpretability of the harmonized values [30]. |

Experimental Protocols & Validation

Protocol 1: Standard ComBat Harmonization Workflow for Feature Data

This protocol details the steps for harmonizing quantitative biomarkers (e.g., SUV metrics, radiomic features, or pre-processed DNA methylation beta values) using the ComBat method [30].

1. Pre-harmonization Visualization:

- Generate a PCA plot colored by batch to visualize the initial severity of the batch effect.

- Generate a boxplot or violin plot of your key features, colored by batch, to inspect distribution differences.

2. ComBat Execution:

- Specify the

batchvector. - Create the model matrix

modcontaining the covariates to preserve. - Run the ComBat function. For a standard implementation, use the

svapackage in R.

3. Post-harmonization Validation:

- Regenerate the PCA plot and feature distribution plots using the

corrected_data. Visually confirm the reduction in batch clustering. - Perform statistical tests (e.g., Kolmogorov-Smirnov test) on feature distributions between batches to confirm the lack of significant differences post-harmonization [30].

Protocol 2: Validation via Simulated Data Experiment

This protocol uses data simulation to verify that ComBat is correctly implemented and configured in your analysis pipeline, as illustrated in [30].

1. Data Simulation:

- Simulate feature data for two or more batches. Introduce known additive (

γ_i) and multiplicative (δ_i) batch effects into the data, following the model:y_ij = α + γ_i + δ_i * ε_ij[30]. - Ensure that a simulated biological variable (e.g., "disease status") is present and unbalanced across batches to test ComBat's ability to preserve it.

2. Harmonization and Analysis:

- Apply the ComBat harmonization to the simulated dataset, including the simulated biological variable in the

modmatrix. - Run ComBat without the biological variable in the

modmatrix for comparison.

3. Outcome Measurement:

- Quantitative: Measure the intra-batch variance versus inter-batch variance before and after harmonization. Successful harmonization should significantly reduce inter-batch variance.

- Qualitative: Inspect PCA plots to confirm that batch separation is minimized while biological group separation is maintained.

- Conclusion: The experiment demonstrates that failure to specify the

modmatrix correctly can lead to the loss of biological signal.

Workflow Visualization

Diagram: ComBat Empirical Bayes Harmonization Workflow

Diagram: ComBat Statistical Model Structure

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for ComBat Harmonization

| Tool / Package Name | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| sva (R Package) | Contains the standard ComBat function for harmonizing normally distributed feature data (e.g., microarray, radiomic features). |

Epigenome-wide association studies (EWAS), medical imaging biomarker analysis [30]. |

| ComBat-seq (R Package) | A variant of ComBat designed specifically for raw RNA-seq count data, which better models the integer nature and variance-mean relationship of sequencing data [22]. | Batch effect adjustment in RNA-seq analysis prior to differential expression. |

| limma (R Package) | Provides the removeBatchEffect function, an alternative method often used on normalized log-counts-per-million (CPM) data within the voom pipeline [22]. |

RNA-seq data analysis when integration into the limma-voom workflow is preferred. |

| PCA & Visualization | Diagnostic plotting (e.g., PCA, boxplots) before and after harmonization is a critical non-statistical "reagent" for assessing batch effect severity and correction success [22]. | Universal quality control step for all batch effect correction procedures. |

| Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test | A statistical test used to check if the distribution of a feature is significantly different between batches before harmonization and to confirm alignment after harmonization [30]. | Quantitative validation of harmonization effectiveness for continuous data. |

| 3M-011 | 3M-011, CAS:642473-62-9, MF:C18H25N5O3S, MW:391.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 5Hpp-33 | 5Hpp-33, CAS:105624-86-0, MF:C20H21NO3, MW:323.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Integrating Batch Covariates in Linear Regression and Mixed Models

FAQs: Core Concepts

What are batch effects and why are they a problem in EWAS? Batch effects are technical sources of variation in high-throughput data introduced by differences in experimental conditions, such as processing date, reagent lot, or sequencing platform [15] [31]. In Epigenome-Wide Association Studies (EWAS), they are problematic because they can introduce noise, reduce statistical power, and, if confounded with the biological variable of interest (e.g., disease status), can lead to spurious associations and misleading conclusions [31] [3].

When should I use a linear mixed model (LMM) over a standard linear regression to handle batch effects? A standard linear regression treats batch as a fixed effect—useful when you have a small number of known, well-defined batches, and these specific batches are of interest [32]. A Linear Mixed Model (LMM) treats batch as a random effect—ideal when the batches in your study (e.g., multiple clinics or labs) represent a random sample from a larger population of batches, and you want your conclusions to generalize to that broader population [32] [33].

Can batch effect correction methods create false positives? Yes. If your study design is unbalanced—for instance, all cases are processed on one chip and all controls on another—applying batch correction algorithms like ComBat can over-adjust the data and introduce thousands of false-positive findings [3]. The optimal solution is a balanced study design where samples from different biological groups are distributed evenly across technical batches [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inflated False Discovery Rate (FDR) after batch correction

Symptoms: A dramatic increase in the number of significant CpG sites after applying a batch correction tool, especially when the study design is unbalanced.

Solution:

- Diagnose: Before correction, perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and check if top PCs are significantly associated with your known batch variables (e.g., chip, row) and, crucially, with your primary variable of interest. Strong confounding is a red flag [3].

- Prevent: The best strategy is prevention through a balanced study design. Randomize or stratify the allocation of samples from different biological groups across all technical batches [3].

- Correct Cautiously: If using an empirical Bayes method like ComBat, provide it only with known, non-confounded batch variables. Be highly skeptical of results from confounded datasets [3].

Problem: Choosing between fixed and random effects for batches

Symptoms: Uncertainty in model specification, leading to models that either overfit or fail to generalize.

Solution: Use the following decision guide to structure your approach:

| Aspect | Fixed Effects for Batch | Random Effects for Batch | |

|---|---|---|---|

| When to Use | Known, specific batches of direct interest (e.g., a few specific processing dates). | Batches are a random sample from a larger population (e.g., multiple clinics, doctors, labs) [32] [33]. | |

| Inference Goal | You want to make conclusions about the specific batches in your model. | You want to generalize conclusions to the entire population of batches, beyond those in your study [32]. | |

| Model Interpretation | Estimates a separate intercept or coefficient for each batch level. | Models batch-specific intercepts as coming from a global normal distribution (mean = 0, variance = (\sigma^2)) [33]. | |

| Example | lm(methylation ~ disease_status + as.factor(batch)) |

`lmer(methylation ~ disease_status + (1 | batch))` |

Problem: Correcting for cell type heterogeneity in EWAS

Symptoms: Uncertainty about whether observed DNA methylation differences are driven by the variable of interest or by differences in underlying cell type proportions.

Solution: Cell type heterogeneity is a major confounder in EWAS. Several reference-free methods exist to capture and adjust for this hidden variability [34].

- SmartSVA: An optimized surrogate variable analysis (SVA) method. It is fast, robust, and controls false positives well, even in scenarios with strong confounding or many differentially methylated positions (DMPs) [34].

- ReFACTor: A PCA-based method that performs well when the signal from DMPs is sparse. It can suffer power loss when there are many DMPs [34].

- RefFreeEWAS: Tends to have high statistical power but may inflate false positive rates in highly confounded scenarios [34].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: A Workflow for Batch Effect Diagnosis and Correction in EWAS

This workflow provides a systematic approach for handling batch effects in DNA methylation array data.

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing: Normalize raw intensity data and perform quality control (QC). Generate M-values for statistical analysis [3].

- Diagnose Batch Effects:

- Perform PCA on the methylation data.

- Test the association of top principal components (PCs) with all known biological (e.g., disease status, age) and technical (e.g., chip, row, processing date) variables.

- Significant association of technical variables with top PCs indicates the presence of batch effects [3].

- Evaluate Study Design: Check if biological groups are confounded with batch. If they are, note that any correction will be risky [3].

- Apply Correction:

- For a balanced design, choose an appropriate method (fixed, random, or algorithmic) based on the nature of your batches.

- For known batches, include them as covariates in a linear model (

lm) or use ComBat. - For unmeasured or numerous batches, use a random effects model (

lmer) or a reference-free method like SmartSVA to capture hidden factors [34].

- Post-Correction Diagnosis: Repeat PCA after correction. The association between top PCs and batch variables should be removed or greatly reduced, while biological signals should remain.

Protocol: Implementing a Linear Mixed Model with Random Batch Intercepts

Objective: To model DNA methylation data while accounting for the non-independence of samples processed within the same batch, where batches are considered a random sample.

Procedure:

- Model Formulation: The LMM for the methylation value ( y ) of sample ( i ) in batch ( j ) is:

( y{ij} = \beta0 + \beta1 X{ij} + uj + \varepsilon{ij} )

Where:

- ( \beta0 ) is the fixed intercept (global mean).

- ( \beta1 ) is the fixed effect of the predictor variable ( X ) (e.g., disease status).

- ( uj ) is the random intercept for batch ( j ), assumed to be ( uj \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^2u) ).

- ( \varepsilon{ij} ) is the residual error, ( \varepsilon{ij} \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^2\varepsilon) ) [32] [33].

- Implementation in R: The output will provide estimates for the fixed effects (( \beta )) and the variance components (( \sigma^2u ) for batches and ( \sigma^2\varepsilon ) for residuals).

The Scientist's Toolkit

Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Illumina Infinium Methylation BeadChip | Array platform for epigenome-wide profiling of DNA methylation at hundreds of thousands of CpG sites [34] [3]. |

| Bisulfite Conversion Reagent | Treats genomic DNA, converting unmethylated cytosines to uracils, allowing for quantification of methylation status [3]. |

| Reference Panel of Purified Cell Types | Required for reference-based cell mixture adjustment methods (e.g., Houseman method) to estimate cell proportions in heterogeneous tissue samples [34]. |

| ComBat Algorithm | An empirical Bayes method used to adjust for known batch effects in high-dimensional data, available in the R sva package [15] [3]. |

| SmartSVA Algorithm | An optimized, reference-free method implemented in R to capture unknown sources of variation, such as cell mixtures or hidden batch effects [34]. |

| 5-Hydroxylansoprazole | 5-Hydroxylansoprazole, CAS:131926-98-2, MF:C16H14F3N3O3S, MW:385.4 g/mol |

| 7-Aminocephalosporanic acid | 7-Aminocephalosporanic acid, CAS:957-68-6, MF:C10H12N2O5S, MW:272.28 g/mol |

The Chip Analysis Methylation Pipeline (ChAMP) is a comprehensive bioinformatics package specifically designed for the analysis of Illumina Methylation beadarray data, including the 450k and EPIC arrays. It serves as an integrated analysis pipeline that incorporates popular normalization methods while introducing novel functionalities for analyzing differentially methylated regions (DMRs) and detecting copy number aberrations (CNAs) [35]. ChAMP is implemented as a Bioconductor package in R and can process raw IDAT files directly using data import and quality control functions provided by minfi [35].

The fundamental challenge addressed by these pipelines stems from the 450k platform's combination of two different assays (Infinium I and Infinium II), which necessitates specialized normalization approaches [35]. ChAMP tackles this through an integrated workflow that includes quality control metrics, intra-array normalization to adjust for technical biases, batch effect analysis, and advanced downstream analyses including DMR calling and CNA detection [35].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What are the key differences between ChAMP and other available 450k analysis pipelines? A: ChAMP complements other pipelines like Illumina Methylation Analyzer, RnBeads, and wateRmelon by offering integrated functionality for batch effect analysis, DMR calling, and CNA detection beyond standard processing capabilities. Its advantage lies in providing these three additional analytical methods within a unified framework [35].

Q: What are the minimum system requirements for running ChAMP effectively? A: ChAMP has been successfully tested on studies containing up to 200 samples on a personal machine with 8 GB of memory. For larger epigenome-wide association studies, the pipeline requires more memory, and the vignette provides guidance on running it in sequential steps to manage computational requirements [35].

Q: What should I do if my BeadChip shows areas of low or zero intensity after scanning? A: This phenomenon can be caused by bubbles in reagents preventing proper contact with the BeadChip surface. Centrifuge all reagent tubes before use and perform a system flush before running the experiment. Notably, due to the randomness and oversampling characteristics of BeadChips, small low-intensity areas may not negatively affect final data quality [36].

Q: How can I resolve issues when the iScan system cannot find all fiducials during scanning? A: This problem often occurs when the XC4 coating is not properly removed from BeadChip edges. Rewipe the edges of BeadChips with ProStat EtOH wipes and rescan. Also verify that BeadChips are seated correctly in the BeadChip carrier [36].

Q: My experiment yielded a low assay signal but normal Hyb controls - what does this indicate? A: This pattern suggests a sample-dependent failure that may have occurred during steps between amplification and hybridization. Repeat the experiment and verify that a DNA pellet formed after precipitation and that the pellet dissolved properly during resuspension (the blue color should disappear completely) [36].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Pre-Hybridization Problems

Table: Pre-Hybridization Issues and Solutions

| Symptom | Probable Cause | Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| No blue pellet observed after centrifugation | Degraded DNA sample or improperly mixed solution | Invert plate several times and centrifuge again; if pellets don't appear, repeat Amplify DNA step [36] |

| Blue color on absorbent pad after supernatant decanted | Insufficient centrifugation speed or delayed supernatant removal | Samples are lost; repeat Amplify DNA step and verify centrifuge program [36] |

| Blue pellet won't dissolve after vortexing | Air bubble preventing mixing or insufficient vortex speed | Pulse centrifuge to remove bubble and revortex at 1800 rpm for 1 minute [36] |

Hybridization and Staining Issues

Table: Hybridization and Staining Problems