Histone Variants and Chromatin Dynamics: Master Regulators of Cell Fate in Development and Disease

This article synthesizes current knowledge on how histone variants, the non-allelic isoforms of canonical histones, act as pivotal regulators of chromatin dynamics to control cell fate decisions.

Histone Variants and Chromatin Dynamics: Master Regulators of Cell Fate in Development and Disease

Abstract

This article synthesizes current knowledge on how histone variants, the non-allelic isoforms of canonical histones, act as pivotal regulators of chromatin dynamics to control cell fate decisions. Targeting researchers and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational mechanisms by which variants like H3.3, H2A.Z, and macroH2A alter nucleosome structure and stability to influence gene expression during processes such as cellular reprogramming, differentiation, and transdifferentiation. We further review advanced methodological approaches, including cryo-EM and multi-omics, for studying variant incorporation and function. The discussion extends to the consequences of variant dysregulation in disease, offering a comparative analysis of their roles as potential therapeutic targets in cancer and other disorders, thereby bridging fundamental epigenetics with clinical application.

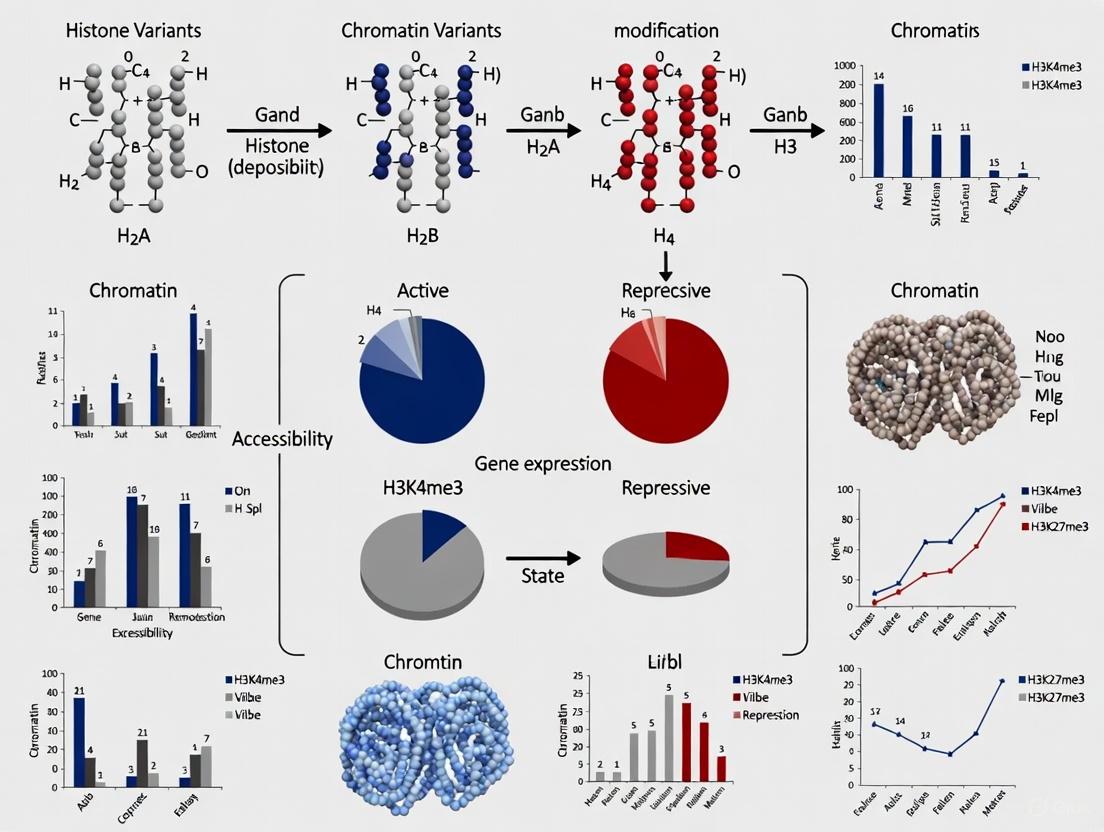

The Architectural Blueprint: How Histone Variants Fundamentally Reshape Chromatin and Cell Identity

In eukaryotic cells, genomic DNA is packaged into chromatin, whose fundamental repeating unit is the nucleosome. Each nucleosome consists of approximately 146 base pairs of DNA wrapped around an octamer of core histone proteins—two each of H2A, H2B, H3, and H4 [1]. The precise composition of this octamer is not uniform across the genome; rather, it incorporates specialized histone isoforms that confer distinct structural and functional properties to specific chromatin regions. This architectural duality arises from two evolutionarily distinct pathways: the replication-coupled (RC) pathway for canonical histones and the replication-independent (RI) pathway for histone variants [2] [3] [4]. These pathways operate under fundamentally different regulatory principles and serve complementary biological functions, ultimately enabling the dynamic packaging of DNA that must accommodate diverse nuclear processes including transcription, DNA repair, and chromosome segregation.

The strategic replacement of canonical histones with specialized variants represents a crucial epigenetic mechanism for regulating chromatin dynamics without altering the underlying DNA sequence [1] [4]. This review delineates the core principles distinguishing histone variants from their canonical counterparts, with particular emphasis on their synthesis, deposition mechanisms, and functional specialization within the context of cell fate determination. Understanding these mechanisms provides critical insights into how chromatin plasticity contributes to developmental programming and disease pathogenesis, offering potential avenues for therapeutic intervention in cancer and other disorders characterized by epigenetic dysregulation.

Fundamental Distinctions: Canonical Histones versus Histone Variants

Definition and Genomic Organization

Canonical histones represent the predominant forms incorporated into chromatin during DNA replication, serving as the primary architectural components of the nucleosomal repeat. In contrast, histone variants are specialized isoforms that differ in amino acid sequence from their canonical counterparts and confer unique properties to nucleosomes [1] [2]. These sequence variations, which may involve as few as one to several amino acid substitutions, occur predominantly in the structurally critical domains of the histone fold motif or N-terminal tails, thereby altering nucleosome stability, dynamics, and interaction with chromatin-associated proteins [1].

The genomic organization and expression patterns of these two histone classes reflect their distinct biological roles. Canonical histones are typically encoded by multigene clusters that are coordinately regulated during the cell cycle, whereas histone variants are usually encoded by single or limited-copy genes scattered throughout the genome [2] [3]. This fundamental genetic distinction underscores the specialized regulatory requirements for histone variant incorporation outside of S-phase.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Canonical Histones versus Histone Variants

| Characteristic | Canonical Histones | Histone Variants |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Organization | Tandemly repeated multigene clusters [5] | Single or limited-copy genes [2] [3] |

| mRNA Processing | Non-polyadenylated, stem-loop structure [2] [3] | Polyadenylated [2] [3] |

| Expression Pattern | Cell cycle-regulated (S-phase specific) [4] | Constitutive throughout cell cycle [1] [4] |

| Deposition Mechanism | Replication-coupled (RC) [4] | Replication-independent (RI) [4] |

| Primary Function | Bulk chromatin assembly during DNA replication [1] | Specialized functions in transcription, repair, differentiation [1] [2] |

Key Sequence Variations and Structural Consequences

The minimal sequence differences between canonical histones and their variant counterparts can profoundly impact nucleosome structure and function. For example, the H3.3 variant differs from canonical H3 at only four amino acid positions, yet these changes alter its interaction with specific chaperone complexes and promote its enrichment at actively transcribed genes [6]. Similarly, H2A.Z features sequence variations in the dimerization interface and L1 loop that destabilize nucleosomes and facilitate transcriptional activation [4]. The macroH2A variant contains an extensive C-terminal non-histone region that promotes chromatin compaction and gene repression [2] [3]. These strategically positioned sequence modifications enable histone variants to fine-tune chromatin accessibility and functionality at specific genomic loci.

The Replication-Coupled Pathway: Canonical Histone Deposition

Molecular Mechanism and Regulation

The replication-coupled pathway orchestrates the synchronized deposition of canonical histones during S-phase to support the rapid assembly of nascent chromatin behind the replication fork. This process initiates with the transcriptional upregulation of canonical histone genes in early S-phase, producing non-polyadenylated mRNAs that are rapidly processed and translated [2] [4]. The resulting newly synthesized canonical histones are promptly complexed with specific chaperone proteins that prevent nonspecific aggregation and facilitate their targeted delivery to replication sites.

The chromatin assembly factor 1 (CAF-1) complex serves as the principal chaperone in the replication-coupled pathway, directly interacting with the proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) sliding clamp at replication forks [6]. This strategic interaction spatially and temporally couples histone deposition with ongoing DNA synthesis, ensuring the immediate packaging of newly replicated DNA into nucleosomes. The CAF-1 complex mediates the stepwise assembly of H3-H4 tetramers onto DNA followed by the incorporation of H2A-H2B dimers, ultimately establishing the canonical nucleosomal repeat [6]. This coordinated process guarantees the faithful duplication of chromatin structure during cell division and maintains epigenetic information through successive cell generations.

Biological Significance in Genome Integrity

The replication-coupled pathway fulfills the essential quantitative demand for histone proteins during S-phase, when the cellular histone content must precisely double to accommodate the newly replicated DNA. Disruption of this pathway compromises chromatin integrity, leading to DNA damage and genomic instability [1]. The strict cell cycle regulation of canonical histone expression prevents the premature accumulation of histones that could otherwise form toxic aggregates or promiscuously interact with non-DNA partners. By temporally restricting canonical histone synthesis to S-phase, the cell ensures the efficient utilization of metabolic resources while maintaining the fidelity of chromatin assembly—a critical determinant of genome stability and cellular viability.

The Replication-Independent Pathway: Histone Variant Deposition

Molecular Mechanism and Chaperone Systems

In contrast to the replication-coupled pathway, the replication-independent pathway operates throughout the cell cycle to incorporate histone variants at specific chromatin domains in a targeted manner. This pathway employs specialized chaperone complexes that recognize distinct histone variants and facilitate their site-specific deposition via ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes [1] [6]. The replication-independent pathway enables localized nucleosome replacement without requiring DNA synthesis, thereby permitting continuous chromatin remodeling in response to developmental and environmental cues.

The HIRA complex represents a prototypical replication-independent chaperone that specifically recognizes and deposits the H3.3 variant at transcriptionally active loci and regulatory elements [6]. Other specialized chaperones include the DEK protein for H3.3 deposition at heterochromatic regions, the ANP32E-containing complex for H2A.Z-H2B dimer exchange, and the ATRX/DAXX complex for H3.3 deposition at pericentromeric and telomeric repeats [1]. These chaperone systems often collaborate with ATP-dependent remodeling enzymes such as SWI/SNF to evict existing nucleosomes and create opportunities for variant incorporation, thereby establishing functionally specialized chromatin domains with unique biophysical and regulatory properties.

Biological Functions in Chromatin Plasticity

The replication-independent pathway underlies the dynamic nature of chromatin organization, permitting rapid restructuring of nucleosome composition in response to transcriptional demands, DNA damage, and developmental signals. The incorporation of specific variants creates nucleosomes with distinct properties that either promote or antagonize chromatin compaction. For instance, H2A.Z-containing nucleosomes exhibit reduced stability and increased dynamics, facilitating transcriptional activation at promoters and enhancers [2] [4]. Conversely, macroH2A incorporation promotes chromatin condensation and gene silencing, particularly at facultative heterochromatin [2] [3]. The H3.3 variant marks sites of high nucleosome turnover, including actively transcribed genes and regulatory elements, where it often carries post-translational modifications associated with transcriptional competence [6].

Table 2: Major Histone Variants and Their Functional Specializations

| Histone Variant | Primary Chaperone | Genomic Localization | Biological Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| H3.3 | HIRA [6] | Active genes, regulatory elements, telomeres [6] | Transcriptional activation, maintenance of heterochromatin, telomere function [1] [6] |

| H2A.Z | SWR1-like complexes, ANP32E [1] | Promoters, enhancers, insulator elements [2] [4] | Transcriptional regulation, genome stability, anti-silencing [2] [4] |

| macroH2A | ATRX (?) | Facultative heterochromatin, inactive X chromosome [2] [3] | Transcriptional repression, barrier to cellular reprogramming [2] [3] |

| H2A.X | FACT, NAP1L1/4 [2] | Throughout genome, phosphorylated at DNA damage sites [2] | DNA damage signaling, repair pathway recruitment [2] |

| CENP-A | HJURP [1] | Centromeres exclusively [1] | Kinetochore assembly, chromosome segregation [1] |

Experimental Approaches for Studying Histone Dynamics

Methodologies for Investigating Deposition Pathways

Dissecting the complex dynamics of histone deposition requires specialized experimental approaches that can distinguish newly synthesized histones from pre-existing counterparts and track their incorporation into chromatin. The following methodologies represent cornerstone techniques in the field:

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing (ChIP-seq): This powerful technique enables genome-wide mapping of histone variant localization and their associated post-translational modifications. ChIP-seq employs variant-specific antibodies to immunoprecipitate chromatin fragments containing the histone of interest, followed by high-throughput sequencing to identify associated genomic regions [5]. Protocol modifications such as spike-in normalization with exogenous chromatin allow for quantitative comparisons between experimental conditions, such as wild-type versus chaperone knockout cells [7].

SNAP-tag Labeling and Pulse-Chase Experiments: The SNAP-tag system involves fusing a self-labeling protein tag to a histone of interest, enabling temporal tracking of histone incorporation and turnover through pulse-chase experiments [6]. Cells expressing SNAP-tagged histones are briefly incubated with a cell-permeable fluorescent substrate that covalently labels the tag, followed by chase periods to monitor labeled histone localization over time. This approach revealed that H3.3 deposition occurs systematically at pre-existing H3.3-enriched sites, while H3.1 incorporation follows replication fork progression [6].

ATAC-seq (Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin with Sequencing): This technique maps genome-wide chromatin accessibility by using a hyperactive Tn5 transposase to integrate sequencing adapters into accessible genomic regions. ATAC-seq requires fewer cells than traditional DNase-seq and provides insights into nucleosome positioning and occupancy [6] [7]. When applied to HIRA knockout cells, ATAC-seq revealed increased accessibility in compartment A despite loss of H3.3 enrichment, demonstrating that HIRA-mediated H3.3 deposition restricts chromatin accessibility in active regions [6].

Multiome Single-Cell Analysis: This advanced approach simultaneously profiles both the epigenomic and transcriptomic states of individual cells using a combination of scATAC-seq and scRNA-seq [7]. This powerful technique enables the correlation of histone variant dynamics and chromatin accessibility with transcriptional outputs at single-cell resolution, particularly valuable in heterogeneous systems such as developing embryos or tumors where bulk measurements may obscure cell type-specific patterns.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Histone Variant Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Chaperone Knockout Cells | HIRA KO [6], DAXX KO | Determine chaperone-specific functions in variant deposition |

| Histone Tagging Systems | H3.1-SNAP, H3.3-SNAP [6] | Temporal tracking of histone incorporation and turnover |

| Variant-Specific Antibodies | Anti-H3.3, Anti-H2A.Z, Anti-macroH2A | Immunodetection, ChIP, and localization studies |

| Chromatin Remodeler Inhibitors | SWI/SNF complex inhibitors | Dissect requirement of ATP-dependent remodeling |

| Mass Spectrometry Standards | Stable isotope-labeled histone peptides | Quantitative profiling of histone PTMs |

| Single-Cell Multiome Kits | 10× Multiome [7] | Simultaneous profiling of chromatin accessibility and gene expression |

| Zoniporide dihydrochloride | Zoniporide dihydrochloride, MF:C17H18Cl2N6O, MW:393.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Pyocyanin | Pyocyanin, CAS:85-66-5, MF:C13H10N2O, MW:210.23 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Implications for Cell Fate and Disease Pathogenesis

Roles in Cellular Plasticity and Differentiation

Histone variants serve as crucial regulators of cellular identity and plasticity by establishing and maintaining lineage-specific epigenetic landscapes. The dynamic replacement of canonical histones with specific variants at key regulatory loci can either promote or restrain cell fate transitions during development and differentiation. For instance, the H3.3 variant plays essential roles in resetting epigenetic states during dedifferentiation and cellular reprogramming, while macroH2A acts as a barrier to pluripotency by stabilizing differentiated states [2] [3]. The incorporation of H2A.Z at developmental gene promoters creates a poised chromatin configuration that facilitates rapid transcriptional activation upon receipt of appropriate differentiation signals [2] [4].

During inflammation-driven cellular plasticity, histone variants mediate the response to inflammatory cues that promote dedifferentiation or transdifferentiation. Pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, and TNFα induce changes in histone variant incorporation that contribute to the loss of specialized cellular functions, as observed in β-cell dedifferentiation in diabetes [2] [3]. Similarly, the senescence-associated histone variant H2A.J accumulates in aged cells and promotes the expression of pro-inflammatory factors that establish a tissue microenvironment conducive to cellular plasticity and pathology [2]. These findings position histone variants as critical integrators of environmental signals that shape cellular identity in both physiological and pathological contexts.

Connections to Human Disease and Therapeutic Opportunities

Dysregulation of histone variant expression and deposition represents an emerging mechanism in human disease pathogenesis, particularly in cancer, developmental disorders, and neurodegenerative conditions [1]. Mutations in histone variants themselves (so-called "oncohistones") or their associated chaperone complexes can disrupt normal chromatin architecture and gene expression programs, leading to malignant transformation. For example, mutations in the H3.3-specific chaperones DAXX and ATRX are frequently observed in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors and gliomas, while mutations in the H3.3 gene itself (H3F3A) occur in pediatric high-grade gliomas [1].

The unique properties of histone variants and their dedicated deposition machinery present attractive therapeutic targets for epigenetic-based therapies. Small molecules that disrupt the interaction between specific histone variants and their chaperones could potentially modulate variant incorporation at disease-relevant loci without globally affecting chromatin structure. Additionally, the specific expression of certain variants in particular disease contexts might be exploited for targeted drug delivery. For instance, the preferential incorporation of H2A.J in senescent cells could be leveraged to selectively eliminate these cells in age-related diseases, while the abundance of macroH2A in differentiated cells might be targeted to reverse its repression of tumor suppressor genes in cancer [2]. Understanding the precise mechanisms governing variant-specific deposition will be crucial for developing such targeted epigenetic therapies.

The strategic division between replication-coupled canonical histone deposition and replication-independent variant incorporation represents a fundamental organizing principle in eukaryotic chromatin biology. These complementary pathways enable both the bulk packaging of the genome during cell division and the precise, localized modulation of chromatin structure necessary for regulated gene expression, DNA repair, and cellular differentiation. The dedicated chaperone systems that govern histone variant targeting provide the specificity necessary to establish and maintain distinct chromatin domains with unique functional properties.

Future research in this field will likely focus on elucidating the intricate crosstalk between different histone variants and their combined effects on higher-order chromatin organization, understanding how variant-specific PTMs expand the functional repertoire of these specialized histones, and developing technologies to manipulate variant deposition with spatiotemporal precision. As we continue to decipher the complex regulatory networks governing histone variant dynamics, we will gain not only fundamental insights into epigenetic mechanisms but also new therapeutic approaches for the numerous human diseases characterized by epigenetic dysregulation. The continued refinement of our understanding of these core principles will undoubtedly reveal new layers of complexity in how chromatin organization shapes cellular identity and function.

Nucleosomes, the fundamental repeating units of chromatin, are dynamic structures whose properties are profoundly influenced by the incorporation of specialized histone variants. This technical review delineates the mechanisms by which histone variants, with a focus on H2A.Z and H3.3, directly alter nucleosome stability, dynamics, and DNA accessibility. Grounded in molecular dynamics simulations, biophysical analyses, and genome-wide studies, we present evidence that variant-driven changes in nucleosome architecture serve as a critical regulatory layer for DNA-templated processes. Within the broader context of cell fate research, understanding these structural impacts is essential for deciphering how epigenetic information guides development, differentiation, and disease pathogenesis, offering novel targets for therapeutic intervention in cancer and other disorders.

In eukaryotes, genomic DNA is packaged into chromatin, with the nucleosome core particle as its fundamental subunit, consisting of approximately 147 base pairs of DNA wrapped around an octamer of histone proteins (two copies each of H2A, H2B, H3, and H4). Histone variants are non-allelic isoforms of canonical histones that differ in their primary amino acid sequence, expression timing, and incorporation mechanisms [8] [9]. Unlike canonical histones whose expression is confined to S-phase, most histone variants are expressed throughout the cell cycle and can be incorporated into chromatin in a replication-independent manner, enabling dynamic chromatin remodeling in response to cellular cues [9] [3].

The H2A family exhibits the greatest sequence divergence and largest number of variants, including H2A.Z, H2A.X, and macroH2A [9]. These variants differ predominantly in their C-terminal domains, strategically positioned at the DNA entry/exit site, and in the L1 loop, an interface for H2A-H2B dimer interactions [9]. Similarly, the H3 variant H3.3 differs from canonical H3 by only a few amino acids yet confers distinct functional properties [10] [11]. The incorporation of these variants alters nucleosome physical properties, influencing higher-order chromatin folding and creating functionally distinct genomic domains essential for transcription, DNA repair, and cell cycle progression [9] [12]. This review synthesizes current mechanistic insights into how variant incorporation structurally reshapes nucleosomes to regulate DNA accessibility.

Molecular Mechanisms of Nucleosome Destabilization

Spontaneous DNA Unwrapping and Nucleosome Gapping

Molecular dynamics simulations reveal that incorporation of the H2A.Z variant fundamentally alters DNA-histone interactions. In canonical nucleosomes, spontaneous DNA unwrapping is limited. In contrast, H2A.Z incorporation facilitates spontaneous DNA unwrapping of approximately forty base pairs from both ends, leading to nucleosome gapping and increased histone plasticity [8]. This unwrapping occurs asymmetrically, influenced by nucleosomal DNA sequence, but the overall magnitude is significantly enhanced in H2A.Z nucleosomes compared to their canonical counterparts [8].

The energy barrier for DNA unwrapping is substantially reduced in H2A.Z-containing nucleosomes. Free-energy profile calculations demonstrate that in canonical H2A nucleosomes, an energy of ~2 kcal/mol is required to unwrap ~5 base pairs, and ~6 kcal/mol for ~17 base pairs. H2A.Z incorporation reduces this energy barrier by several kcal/mol and enables a wider range of unwrapping modes [8]. This reduced stability is reflected in MM/GBSA calculations showing lower overall histone-DNA binding energy in H2A.Z systems [8].

Key Structural Determinants in H2A Variants

The structural impacts of H2A variants are primarily mediated through specific domains:

- C-terminal Tail: The H2A C-terminus is located at the DNA entry/exit site. In H2A.Z, this domain plays a major role in mediating pronounced DNA unwrapping. Variations in this region directly influence DNA binding affinity and nucleosome stability [8] [9].

- L1 Loop: This region in the histone fold serves as the interaction interface between H2A-H2B dimers. The L1 loop shows high sequence divergence among H2A variants and affects dimer-tetramer interactions within the nucleosome [9].

- Acidic Patch: This surface feature, important for internucleosomal contacts and higher-order chromatin structure, is altered between different H2A variants, potentially affecting chromatin fiber compaction [9].

Table 1: Structural Domains of H2A Variants and Their Functional Impacts

| Structural Domain | Location | Functional Role | Impact of Variation |

|---|---|---|---|

| C-terminal Tail | DNA entry/exit site | Modulates DNA end binding | Alters DNA unwrapping kinetics and nucleosome stability |

| L1 Loop | Histone fold domain | Mediates H2A-H2B dimer interaction | Affects dimer stability and tetramer association |

| Acidic Patch | Nucleosome surface | Facilitates internucleosomal contacts | Changes higher-order chromatin folding |

Synergistic Destabilization by H3.3 and H2A.Z Combinations

Nucleosomes containing both H3.3 and H2A.Z exhibit extreme instability. Biochemical studies of native nucleosome core particles show that H3.3-containing nucleosomes are unusually sensitive to salt-dependent disruption, losing H2A/H2B or H2A.Z/H2B dimers more readily than their canonical counterparts [11]. Intriguingly, nucleosomes containing both H3.3 and H2A.Z are even less stable than those containing H3.3 with canonical H2A [11]. This establishes a hierarchy of nucleosome stabilities based on variant composition, with H3.3/H2A.Z double-variant nucleosomes being the most labile.

This synergistic destabilization has significant biological implications. Double-variant nucleosomes are concentrated at promoters and enhancers of transcriptionally active genes, as well as in coding regions of highly expressed genes, suggesting their instability facilitates transcription factor binding and polymerase progression [11].

Quantitative Analysis of Nucleosome Stability and Dynamics

Energetics of DNA Unwrapping

The energy landscape for DNA unwrapping differs substantially between canonical and variant-containing nucleosomes. Quantitative analyses reveal that H2A.Z incorporation not only reduces the energy barrier for unwrapping but also widens the range of accessible DNA configurations. Two-dimensional free-energy landscapes as a function of DNA radius of gyration and total DNA-histone contacts show that canonical nucleosomes occupy a smaller range of Rg values coupled with a larger number of DNA-histone contacts, while H2A.Z nucleosomes explore more extended DNA configurations with fewer contacts [8].

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Nucleosome Stability Parameters

| Parameter | Canonical Nucleosomes | H2A.Z-Containing Nucleosomes | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spontaneous DNA Unwrapping | Up to 22 bp total from both ends | Up to 45 bp total from both ends | Molecular Dynamics Simulations [8] |

| Energy Barrier for ~5 bp Unwrapping | ~2 kcal/mol | Reduced by several kcal/mol | Free-Energy Profile Calculation [8] |

| Salt-Induced Dimer Loss | More stable | Less stable, especially with H3.3 | Salt Disruption Assay [11] |

| Histone-DNA Binding Energy | Higher absolute value | Lower absolute value | MM/GBSA Calculations [8] |

Nucleosome Turnover Kinetics

Genome-wide studies of H3.3 incorporation dynamics in mouse embryonic fibroblasts reveal distinct categories of nucleosome turnover:

- Rapid turnover: At enhancers and promoters (associated with active marks: H3K4me1, H3K4me3, H3K9ac, H3K27ac, and H2A.Z)

- Intermediate turnover: In gene bodies

- Slow turnover: At telomeres and heterochromatic regions [10]

These turnover rates are negatively correlated with H3K27me3 at regulatory regions and with H3K36me3 at gene bodies [10]. The rapid turnover at regulatory elements suggests variant-incorporated nucleosomes are continuously exchanged, maintaining chromatin in an accessible state permissive for transcription factor binding.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Molecular Dynamics Simulation Protocols

Recent insights into nucleosome dynamics have been enabled by advanced computational approaches:

- System Setup: Construction of homotypic nucleosome systems containing canonical H2A or H2A.Z variant using 187 bp of native DNA sequence from the TP53 gene (147 bp nucleosomal sequence + 20 bp linker DNA segments on each end) [8].

- Simulation Parameters: Multiple independent microsecond-long all-atom molecular dynamics simulations (typically 7 μs) for each system using explicit solvent models [8].

- Analysis Metrics: Quantification of DNA unwrapping by measuring protein-DNA contacts; free energy calculations using umbrella sampling or similar enhanced sampling techniques; DNA radius of gyration and histone plasticity assessments [8].

These simulations have revealed that H2A.Z deposition enhances DNA and histone dynamics, with the C-terminal tail mediating pronounced DNA unwrapping and the N-terminal tail accounting for increased nucleosome gapping [8].

Biochemical Stability Assays

Biophysical measurements of nucleosome stability employ several established techniques:

- Salt-Disruption Assays: Subjecting native nucleosome core particles to increasing salt concentrations to measure the release of H2A/H2B dimers. H3.3-containing nucleosomes show significantly enhanced sensitivity to salt-dependent disruption [11].

- Thermal Denaturation Profiles: Monitoring nucleosome stability through temperature-dependent unfolding using spectroscopic methods.

- Native Nucleosome Preparation: Isolation of nucleosome core particles via micrococcal nuclease digestion of nuclei followed by sucrose gradient centrifugation for purification [11].

Genome-Wide Incorporation Dynamics

Tracking variant incorporation genome-wide involves sophisticated molecular biology approaches:

- Inducible Expression Systems: Generation of cell lines carrying inducible epitope-tagged histone variants (e.g., HA/FLAG-tagged H3.3 under tetracycline-responsive promoter) [10].

- Replication-Independent Assays: Cell cycle arrest using aphidicolin (a DNA polymerase inhibitor) to isolate replication-independent incorporation [10].

- ChIP-Seq Time Course: Chromatin immunoprecipitation with high-throughput sequencing at multiple time points after variant induction to map incorporation kinetics [10].

- Data Analysis: Identification of regions with rapid, intermediate, and slow turnover rates; correlation with histone modification marks and genomic features [10].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for genome-wide analysis of histone variant turnover kinetics

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying Histone Variant Dynamics

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Epitope-Tagged Histone Variants (e.g., HA/FLAG-H3.3) | Enable tracking and purification of newly incorporated histones | Inducible expression systems to measure replication-independent incorporation [10] |

| Cell Cycle Inhibitors (e.g., Aphidicolin) | Arrest cells at G1/S boundary | Isolate replication-independent histone incorporation events [10] |

| Histone-Specific Antibodies | Immunoprecipitation of variant-containing nucleosomes | ChIP-Seq, Western blot analysis of histone composition [10] [11] |

| Molecular Dynamics Software (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER) | All-atom simulations of nucleosome dynamics | Study DNA unwrapping mechanisms and energy landscapes [8] |

| Sucrose Gradient Centrifugation | Separation of nucleosome core particles | Biochemical preparation of native nucleosomes for stability assays [11] |

| Micrococcal Nuclease (MNase) | Digest linker DNA | Preparation of nucleosome core particles from chromatin [11] |

| 8,11,14-Eicosatriynoic Acid | 8,11,14-Eicosatriynoic Acid, MF:C20H28O2, MW:300.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Indomethacin N-octyl amide | Indomethacin N-octyl amide, MF:C27H33ClN2O3, MW:469.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Functional Consequences for Chromatin Biology

Regulation of DNA Accessibility for Transcription

The primary functional consequence of variant-induced nucleosome destabilization is enhanced DNA accessibility. H2A.Z-containing nucleosomes demonstrate increased mobility and DNA accessibility to transcriptional machinery and other chromatin components [8]. This is particularly important at transcription start sites (TSS), where H2A.Z is prominently enriched [8] [9]. The reduced energy barrier for DNA unwrapping facilitates transcription factor binding and polymerase progression.

In embryonic stem cells, H3.3 is found at promoters of both active and inactive genes, suggesting a role in maintaining plasticity for developmental gene regulation [10] [13]. The combination of H3.3 and H2A.Z creates nucleosomes of exceptionally low stability that are strategically positioned at key regulatory elements, poising them for rapid activation or repression in response to developmental signals [11] [13].

Implications for DNA Repair Pathways

Histone variants play crucial roles in DNA damage response and repair. H2A.X, defined by its C-terminal SQ[E/D]Φ motif, becomes phosphorylated (γH2A.X) at serine 139 following DNA damage, serving as a key marker for double-strand breaks and recruiting repair factors [9] [12]. The variant-dependent chromatin environment influences repair pathway choice—H2A.Z incorporation can destabilize nucleosomes to make damaged DNA more accessible to repair machinery [12].

Roles in Cell Fate Decisions

Histone variants are integral to epigenetic regulation of cell identity. They contribute to the chromatin landscape that maintains pluripotency in stem cells and guides lineage commitment [3] [13]. During cellular reprogramming and transdifferentiation, changes in variant incorporation precede and facilitate changes in gene expression patterns. For example, the loss of macroH2A enhances reprogramming efficiency, while H2A.Z dynamics are associated with inflammatory gene regulation during cell fate transitions [3].

Figure 2: Functional cascade from histone variant incorporation to biological outcomes

The structural impact of histone variant incorporation on nucleosome stability, dynamics, and DNA accessibility represents a fundamental mechanism in epigenetic regulation. Through specific alterations in histone-DNA and histone-histone interactions, variants like H2A.Z and H3.3 create nucleosomes with distinct biophysical properties that directly influence DNA accessibility. The quantitative parameters and experimental approaches outlined in this review provide researchers with a framework for investigating these phenomena in various biological contexts.

Future research directions should focus on elucidating the combinatorial effects of multiple variants within single nucleosomes, the interplay between variants and post-translational modifications, and the development of small molecules that specifically target variant-containing nucleosomes. As we continue to decipher how variant-driven chromatin states influence cell fate decisions, new opportunities will emerge for therapeutic interventions in cancer and other diseases characterized by epigenetic dysregulation. The integration of structural biology, computational modeling, and genome-wide approaches will be essential for advancing our understanding of these fundamental regulatory mechanisms.

In the eukaryotic nucleus, genomic DNA is packaged into chromatin, the basic unit of which is the nucleosome. While canonical histones form the bulk of nucleosomes, specialized histone variants introduce structural and functional diversity that is instrumental in regulating all DNA-based processes. These variants, characterized by distinct amino acid sequences, expression patterns, and deposition mechanisms, serve as key epigenetic regulators of gene expression, genome stability, and cellular identity [14] [15]. Their dynamic incorporation into chromatin creates a complex regulatory landscape that influences cell fate decisions, and growing evidence implicates their dysregulation in diseases, including cancer. This review provides a technical deep dive into four critical histone variants—H2A.Z, H3.3, macroH2A, and CENP-A—detailing their unique properties, deposition machinery, functional roles, and the experimental tools used to dissect their mechanisms. Understanding these "key players" is paramount for advancing fundamental chromatin research and developing novel therapeutic strategies.

The H2A.Z Variant: A Janus-Faced Regulator of Transcription

Biochemical Properties and Deposition Machinery

H2A.Z is an evolutionarily conserved H2A variant that shares approximately 60% sequence identity with its canonical counterpart [8]. In chordates, two main isoforms exist, H2A.Z.1 and H2A.Z.2, encoded by the H2AFZ and H2AFV genes, respectively. They differ in only three amino acids, yet exhibit specialized functions [14]. A primate-specific, alternatively spliced isoform, H2A.Z.2.2, has also been identified, featuring a distinct C-terminus that results in less stable nucleosomes [14]. The incorporation of H2A.Z into chromatin is replication-independent and is mediated by the SWR1 (or SRCAP in mammals) chromatin remodeling complex, which catalyzes the ATP-dependent exchange of canonical H2A-H2B dimers for H2A.Z-H2B dimers [14].

Functional Roles and Impact on Nucleosome Dynamics

H2A.Z is enriched at promoters, enhancers, and the transcription start sites (TSSs) of active and poised genes, implicating it in transcriptional regulation [14] [8]. However, its role is context-dependent, as it can be associated with both transcriptional activation and repression. Recent molecular dynamics simulations have shed light on its mechanism, revealing that H2A.Z incorporation substantially decreases the energy barrier for DNA unwrapping, leading to the spontaneous unwrapping of up to 40 base pairs from nucleosome ends [8]. This increased DNA accessibility promotes the binding of transcription factors and the transcriptional machinery. The C-terminal tail of H2A.Z is a major driver of this DNA unwrapping, while its N-terminal tail contributes to nucleosome gapping [8]. Beyond transcription, H2A.Z is involved in DNA double-strand break repair, cell cycle progression, and chromosome segregation [14] [8].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of the H2A.Z Variant

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Encoding Genes | H2AFZ (H2A.Z.1), H2AFV (H2A.Z.2) [14] |

| Key Chaperone/Complex | SWR1/SCRAP complex [14] |

| Primary Genomic Localization | Promoters, Enhancers, Transcription Start Sites (TSS) [14] [8] |

| Primary Functions | Transcriptional Regulation, DNA Repair, Cell Cycle Progression [14] |

| Nucleosome Stability | Decreases energy barrier for DNA unwrapping, increases dynamics and accessibility [8] |

Experimental Insights and Technical Approaches

Studies on H2A.Z often combine multiple techniques. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) is used to map its genome-wide localization. To probe its effect on nucleosome dynamics, all-atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have been instrumental, as they can model spontaneous DNA unwrapping events over microsecond timescales [8]. Furthermore, Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) can be used to study the mobility and exchange kinetics of H2A.Z isoforms in live cells, as H2A.Z.1 and H2A.Z.2 exhibit different turnover rates [14].

The H3.3 Variant: A Marker of Dynamic Chromatin

Distinct Biosynthesis and Incorporation Pathways

H3.3 is a replication-independent histone H3 variant that differs from canonical H3.1 by only four to five amino acids [15] [16]. These subtle changes are critical for its recognition by specific chaperone complexes. Unlike canonical H3 genes, which are clustered and intronless, H3.3 is encoded by two separate, intron-containing genes (H3F3A and H3F3B) that produce polyadenylated mRNAs expressed throughout the cell cycle [15] [17]. This allows for H3.3 incorporation outside of S-phase. Two major chaperone complexes mediate its deposition: the HIRA complex deposits H3.3 in gene bodies and regulatory elements of active genes, while the DAXX-ATRX complex deposits H3.3 into telomeres, pericentric heterochromatin, and endogenous retroviral elements [15] [16].

Dual Role in Active and Repressive Chromatin

Traditionally viewed as a mark of active chromatin, H3.3 is enriched in covalent modifications associated with transcription, such as H3K4me3 and H3K36me3 [15] [16]. It is found across the bodies of actively transcribed genes and at promoters. However, H3.3 also localizes to silent loci, including pericentric heterochromatin and telomeres, highlighting its "double-faced" nature [16]. This repressive role is linked to the DAXX-ATRX pathway and the H3K9me3 modification [15]. H3.3 is crucial for maintaining epigenetic memory, paternal chromatin assembly in zygotes, and transcriptional recovery after genotoxic stress [15]. Its mutation is implicated in several cancers, further underscoring its biological importance.

Table 2: Key Characteristics of the H3.3 Variant

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Encoding Genes | H3F3A, H3F3B [15] |

| Key Chaperone Complexes | HIRA Complex (euchromatin), DAXX-ATRX Complex (heterochromatin) [15] |

| Primary Genomic Localization | Gene bodies of active genes, promoters, enhancers, telomeres, pericentric heterochromatin [15] [16] |

| Primary Functions | Transcriptional Activation, Maintenance of Epigenetic Memory, Telomere Maintenance [15] |

| Nucleosome Stability | Subtle effects; its combination with H2A.Z significantly promotes DNA accessibility [8] |

Experimental Insights and Technical Approaches

Mapping H3.3 localization relies heavily on ChIP-seq with isoform-specific antibodies. To dissect its distinct deposition pathways, genetic models with knockouts or knockdowns of specific chaperones like HIRA or DAXX are used, followed by genomic and cellular phenotyping [15]. The use of inducible systems has been valuable for studying the replication-independent incorporation of H3.3 and its role in processes like UV damage repair [15].

The macroH2A Variant: A Bulky Guardian of Transcriptional Repression

Unique Structural Organization

macroH2A is a vertebrate-specific H2A variant with a highly unusual tripartite structure. Its N-terminal region is ~64% identical to canonical H2A, but it is linked to a large (~25 kDa) non-histone region (NHR) via a linker sequence [18]. This makes macroH2A almost three times the size of canonical H2A. The NHR folds into a structure found in a functionally diverse group of proteins, and it associates with histone deacetylases (HDACs), influencing the acetylation status of nucleosomes [18].

Functions in Gene Repression and Cellular Plasticity

macroH2A is a potent transcriptional repressor. It is enriched on the inactive X chromosome in female mammalian cells, where it contributes to the maintenance of gene silencing [18]. Mechanistically, macroH2A-containing nucleosomes are inherently more stable and inhibit the chromatin remodeling activity of the SWI/SNF complex [2]. Furthermore, the macroH2A NHR can block specific transcription factor binding, such as NF-κB, to nucleosomes, thereby repressing the expression of pro-inflammatory genes [2]. Its role extends to limiting cellular plasticity, as it acts as a barrier to somatic cell reprogramming and is downregulated during dedifferentiation and transdifferentiation processes [2].

Table 3: Key Characteristics of the macroH2A and CENP-A Variants

| Feature | macroH2A | CENP-A |

|---|---|---|

| Encoding Genes | H2AFY | CENPA |

| Key Chaperone/Complex | NAP1-like chaperones? (Less defined) | HJURP (Holilday Junction Recognition Protein) [19] |

| Primary Genomic Localization | Inactive X Chromosome, Facultative Heterochromatin [18] | Centromeres [19] |

| Primary Functions | Transcriptional Repression, X-Chromosome Inactivation, Barrier to Dedifferentiation [18] [2] | Epigenetic Specification of Centromere Identity, Kinetochore Assembly [19] |

| Nucleosome Stability | Increases nucleosome stability and rigidity [18] | Altered stability; forms a more rigid and compact nucleosome [19] |

The CENP-A Variant: The Epigenetic Blueprint of the Centromere

The Key Epigenetic Mark for Centromere Identity

CENP-A (CENPA), a histone H3 variant also known as cenH3, is the fundamental epigenetic determinant of centromere identity in most eukaryotes [19]. It replaces canonical H3 in centromeric nucleosomes and is essential for recruiting the kinetochore, the protein complex that mediates attachment to the mitotic spindle. CENP-A shares less than 51% sequence identity with canonical H3 and forms a nucleosome that wraps only about 121 base pairs of DNA, creating a more rigid and compact structure [17] [19]. A critical region of its histone fold domain, the CENP-A targeting domain (CATD), confers conformational rigidity and is necessary and sufficient for targeting to the centromere [19].

Replenishment and Cell Cycle Control

The maintenance of CENP-A at centromeres is epigenetically inherited, independent of the underlying DNA sequence. Its deposition is tightly coupled to the cell cycle. Unlike canonical H3, which is loaded during S-phase, CENP-A is incorporated into centromeres during late G2 and mitosis in animal cells [19]. This replication-independent loading is mediated by its dedicated chaperone, HJURP (Holliday Junction Recognition Protein) [19]. Precise regulation of CENP-A levels is critical, as its overexpression can lead to misincorporation into chromosome arms and genomic instability, a phenomenon observed in some cancers [19].

Experimental Insights and Technical Approaches

Studying CENP-A often involves immunofluorescence and super-resolution microscopy to visualize its precise localization at centromeres. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) is used to define its binding across centromeric repeats. A key methodology for understanding its function is gene replacement in model systems like human cells and fission yeast, which allows researchers to dissect the biochemical features that encode centromere identity [20] [19]. Furthermore, biochemical reconstitution of CENP-A nucleosomes has been crucial for understanding their unique structural properties [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Histone Variant Studies

| Reagent/Method | Function/Application | Key Experimental Use |

|---|---|---|

| Isoform-Specific Antibodies | Immunodetection of specific histone variants | Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP), Immunofluorescence, Western Blotting [14] [19] |

| All-Atom Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations | In silico modeling of nucleosome dynamics | Probing DNA unwrapping energetics and histone tail functions [8] |

| Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) | Measuring protein mobility and kinetics in live cells | Analyzing the exchange rate and turnover of histone variants like H2A.Z [14] |

| Chaperone Knockout/Knockdown Models | Genetic disruption of specific deposition pathways | Elucidating the functional consequences of variant mis-incorporation (e.g., HIRA for H3.3, HJURP for CENP-A) [15] [19] |

| Gene Replacement & Mutagenesis | Swapping specific protein domains in vivo | Defining functional domains, such as the CENP-A CATD, that confer unique properties [20] [19] |

| Quantitative Mass Spectrometry | Profiling histone post-translational modifications (PTMs) | Identifying variant-specific modification landscapes [14] [5] |

| 4-Phenyl-1,2,3-thiadiazole | 4-Phenyl-1,2,3-thiadiazole, CAS:25445-77-6, MF:C8H6N2S, MW:162.21 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Trimidox | Trimidox, CAS:95933-74-7, MF:C7H8N2O4, MW:184.15 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Integrated View: Crosstalk and Coordination in Cell Fate

The functions of histone variants are highly interconnected. A prime example is the cooperation between H2A.Z and H3.3. Nucleosomes containing both H2A.Z and H3.3 are enriched at regulatory regions and exhibit the highest degree of DNA accessibility, facilitating transcription factor binding and acting as a mark for "nucleosome-free regions" [8] [16]. Conversely, macroH2A often opposes the action of these activating variants, establishing stable repressive domains. The coordinated action of these variants creates a complex regulatory network that governs chromatin dynamics. During processes like cell dedifferentiation and transdifferentiation, the levels and genomic distribution of these variants are dynamically altered. For instance, H3.3 and H2A.Z are associated with resetting epigenetic states, while macroH2A acts as a barrier to this plasticity [2]. Understanding this intricate interplay is crucial for manipulating cell fate in regenerative medicine and combating diseases like cancer, where the expression of these variants is frequently dysregulated.

Visualizing Histone Variant Deposition and Function

The following diagram illustrates the specialized deposition pathways and primary functional niches of the four core histone variants within the nucleus.

The eukaryotic genome is packaged into chromatin, a dynamic DNA-protein complex whose basic unit is the nucleosome. Nucleosome composition is not static; it is shaped by the incorporation of specialized histone variants that confer unique properties to chromatin, influencing all DNA-templated processes. The precise deposition and exchange of these variants are orchestrated by a sophisticated chaperone network, comprising histone chaperones and their associated co-factors. This network ensures the correct spatial and temporal incorporation of variants to establish and maintain functional chromatin domains. Recent research has illuminated how this machinery is fundamental to cell fate decisions, and its dysregulation is implicated in diseases such as cancer and neurodevelopmental disorders. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical review of the core principles of the chaperone network, detailing its specialized machinery for histone variant deposition and exchange, and framing its critical role within the broader context of chromatin dynamics in cell identity.

Core histones (H2A, H2B, H3, H4) assemble into an octamer around which 147 base pairs of DNA are wrapped to form the nucleosome [21]. The histone H3 family exemplifies the diversity of histone proteins, consisting of several variants with distinct expression patterns and functions. Canonical histones H3.1 and H3.2 are synthesized during the S-phase and deposited in a replication-coupled (RC) manner, enabling chromatin assembly on newly replicated DNA [17]. In contrast, the replacement variant H3.3 is expressed throughout the cell cycle and deposited in a replication-independent (RI) manner, facilitating histone turnover in non-dividing cells [17]. A more divergent variant, CENP-A, is specifically incorporated at centromeres to define centromeric identity and ensure proper chromosome segregation [17].

The presence of histone variants directly influences nucleosome stability and dynamics. For instance, H3.3-containing nucleosomes are intrinsically less stable, which contributes to the dynamic nature of chromatin at active regulatory elements [22]. However, histones are inherently prone to promiscuous interactions with other macromolecules due to their highly basic charge. To prevent aggregation and spurious interactions with DNA or RNA, histone chaperones are required to shield histones and guide them through their cellular life cycle—from synthesis and folding to nuclear import, deposition, and eventual eviction [21] [23]. This network of chaperones does not operate in isolation; it is integrated with chromatin remodelers, histone-modifying enzymes, and the transcriptional machinery to match histone supply with cellular demand, thereby safeguarding the chromatin template and maintaining epigenetic information [21] [23].

The Architecture of the Histone Chaperone Network

The histone chaperone network is a complex system built on both histone-dependent co-chaperone complexes and histone-independent chaperone-chaperone interactions. These interactions allow for a more complete shield around the histone substrate and facilitate the handover of histones between different chaperone pathways [21] [23]. Exploratory interactomics studies have begun to chart this network, revealing both its connectivity and functional specialization.

Table 1: Key Histone H3-H4 Chaperone Complexes and Their Functions

| Chaperone Complex | Primary Histone Substrate | Deposition Pathway | Primary Genomic Localization/Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAF-1 | H3.1-H4 | Replication-Coupled (RC) | Sites of DNA replication; de novo nucleosome assembly [23] |

| HIRA | H3.3-H4 | Replication-Independent (RI) | Active promoters, gene bodies; transcription-coupled deposition [23] [24] |

| ATRX-DAXX | H3.3-H4 | Replication-Independent (RI) | Heterochromatin, telomeres, repetitive elements; promotes H3K9me3 deposition [23] [24] |

| HJURP | CENP-A-H4 | Replication-Independent (RI) | Centromeres; defines centromeric identity [23] [17] |

| sNASP | H3.1/H3.2/H3.3-H4 | Soluble Histone Pool | Cytoplasmic and nuclear soluble histone pool; protects from autophagy [23] |

| ASF1A/B | H3.1/H3.3-H4 | RC & RI (Handoff) | Central hub; hands off H3-H4 to CAF-1 and HIRA complexes [21] [23] |

Network analysis of histone chaperone interactomes reveals a topology with both interconnected and independent arms. ASF1 acts as a central hub, coordinating histone supply by interacting with multiple downstream chaperones, including MCM2 for histone recycling during replication and the CAF-1 and HIRA complexes for de novo deposition [21] [23]. In contrast, the DAXX-ATRX chaperone complex often operates as a largely independent arm of the network, specialized for handling H3.3-H4 destined for heterochromatic regions [23]. This functional segregation allows the cell to maintain distinct histone supply chains for different chromatin environments.

The H3.3-Specific Chaperone Pathways: A Case Study in Specificity

The deposition of the H3.3 variant is a paradigm for chaperone network specialization. Two major complexes, HIRA and ATRX-DAXX, mediate H3.3 incorporation in a mutually exclusive manner, leading to its placement in functionally antagonistic chromatin states [23] [24]. The HIRA complex is responsible for H3.3 deposition at active genes, including promoters and gene bodies, in a transcription-coupled manner [24]. Conversely, the ATRX-DAXX complex deposits H3.3 at heterochromatic regions, including telomeres, pericentromeric regions, and endogenous retroviral elements [23]. DAXX provides a unique functionality to this pathway by recruiting histone methyltransferases like SUV39H1 and SETDB1, thereby promoting H3K9me3 catalysis on new H3.3-H4 prior to its deposition [23]. This provides a molecular mechanism for de novo heterochromatin assembly, linking histone chaperone activity directly to the establishment of a repressive epigenetic mark.

Diagram 1: Specialized H3.3 chaperone pathways determine chromatin state.

Quantitative Dynamics of Histone Exchange

Histone exchange (turnover) is a fundamental process that underlies chromatin plasticity. It involves the eviction of existing histones and their replacement with newly synthesized or alternative variants, effectively resetting the local histone post-translational modification landscape [22]. The development of novel quantitative tools has been critical for mapping exchange dynamics genome-wide.

Experimental Protocol: Histone Exchange Sensors

A powerful method for measuring histone exchange involves the use of genetically encoded histone exchange sensors [22].

1. Principle: The system is based on two components:

- A sensor histone (e.g., H3.3) fused to a C-terminal tag containing a Tobacco Etch Virus (TEV) protease cleavage site, flanked by myc and HA epitope tags.

- A complementary histone (e.g., canonical H2B) fused to the TEV protease.

2. Mechanism: The tagged histones only come into proximity upon co-assembly into the same nucleosome. If the residence time is long enough, the TEV protease cleaves the sensor, releasing the myc tag. A short residence time (rapid exchange) results in eviction before cleavage can occur, preserving the myc tag.

3. Readout: Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) is performed for both the HA tag (reporting on total histone occupancy) and the myc tag (reporting on histone exchange). The myc:HA ratio provides a quantitative measure of regional exchange rates, with a high ratio indicating rapid turnover [22].

Diagram 2: Histone exchange sensor mechanism for measuring turnover.

Quantitative Profiling of Variant-Specific Exchange

Application of the sensor system in mouse Embryonic Stem Cells (mESCs) has yielded variant-specific exchange profiles, summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Variant-Specific Histone Dynamics from Exchange Sensor Studies in mESCs [22]

| Histone Variant | Exchange Correlation with Transcription | Key Genomic Regions with High Exchange | Unexpected Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| H3.3 | Strong Positive | Transcription Start Sites (TSS) of active genes, Active Enhancers | High occupancy and low exchange in heterochromatin. |

| H3.1 (Canonical) | Moderate Positive | Bivalent Promoters (H3K4me3/H3K27me3), Repeat Elements | Considerable exchange in heterochromatin, linked to H3.3 occupancy. |

| H2B (Canonical) | Moderate Positive | Repeat Elements | High dynamics at heterochromatic repeats. |

A key finding was the considerable exchange of canonical H3.1 in heterochromatin and repeat elements, which contrasts with the stable occupancy of H3.3 in these same regions [22]. This suggests that H3.3 acts as a stable mark for heterochromatin, while canonical histones in these regions are more dynamic than previously assumed. Furthermore, depletion of the H3.3 chaperone HIRA reduced H3.1 dynamics at enhancers and promoters, indicating a potential crosstalk where H3.3 deposition influences the turnover of canonical H3.1 [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Methodologies

To dissect the chaperone network, researchers employ a suite of sophisticated molecular, proteomic, and genomic tools.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Investigating the Chaperone Network

| Reagent / Method | Primary Function | Key Application in the Field |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope Labeling (SILAC) & IP-MS | Quantitative interactome profiling. | Identifying histone-dependent and -independent chaperone interactions; charting the chaperone network [23]. |

| Histone Exchange Sensors | Measure locus-specific histone turnover. | Mapping genome-wide exchange rates of histone variants (e.g., H3.1, H3.3, H2B) in unperturbed cells and during development [22]. |

| Histone Binding Mutants (HBM) | Disrupt specific chaperone-histone interactions. | Defining the functional consequences of specific chaperone interactions within the network [23]. |

| QconCAT & SRM Mass Spectrometry | Absolute quantification of chaperone abundance. | Quantifying chaperone copies per cell and estimating protein flux through the network [25]. |

| Genetic Models (Knockout/Knockdown) | Loss-of-function studies. | Establishing the functional requirement of specific chaperones (e.g., HIRA, DAXX) in histone deposition and cell fate [23] [17] [22]. |

| Triapine | Triapine, CAS:236392-56-6, MF:C7H9N5S, MW:195.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| MMP-2 Inhibitor II | MMP-2 Inhibitor II, MF:C16H17NO6S2, MW:383.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Implications for Cell Fate and Disease

The chaperone network is not a static infrastructure; it is dynamically regulated during cellular differentiation and is integral to maintaining cell identity. The expression of specific chaperones is often driven by differentiation transcription factors, rewiring the network to meet the changing needs of the cellular proteome and epigenome [26]. For example, the chaperone complex CAF-1 is known to restrict cellular plasticity, and its suppression can enhance reprogramming of somatic cells into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [17].

Dysregulation of the chaperone network is increasingly linked to disease. Mutations in the H3.3 chaperone ATRX and its partner DAXX are frequently found in cancers, including pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors and gliomas [23]. Similarly, mutations in genes encoding H2A.Z and H3.3 chaperones, such as SRCAP and ATRX-DAXX, have been associated with neurodevelopmental disorders, highlighting the critical importance of precise histone variant deposition for proper brain development [24]. The finding that DAXX recruits H3K9 methyltransferases to new H3.3 provides a direct mechanistic link between a chaperone, histone deposition, and the establishment of a repressive chromatin state that is often disrupted in disease [23].

The chaperone network represents a critical layer of epigenetic regulation, functioning as a specialized and highly coordinated machinery for the deposition and exchange of histone variants. Through variant-specific chaperone complexes and regulated handoff mechanisms, this network ensures the precise marking of genomic domains, from active promoters to silent heterochromatin. The integration of quantitative proteomics, innovative sensor technologies, and genetic models is providing an increasingly resolved picture of network topology and dynamics. As the role of this network in cell fate and disease becomes more apparent, it presents a promising, though complex, therapeutic frontier for modulating epigenetic states in pathological conditions.

Within the nucleus of every cell, the packaging of DNA into chromatin is a dynamic and regulated process, central to all DNA-templated activities. The basic repeating unit of chromatin is the nucleosome, which consists of ~147 base pairs of DNA wrapped around an octamer of core histone proteins—two copies each of H2A, H2B, H3, and H4 [27]. While the foundational structure of the nucleosome is conserved, its functional properties can be profoundly altered by the incorporation of specialized histone variants. These variants are non-allelic isoforms of the core histones that differ in their amino acid sequence, timing of expression, and genomic deposition mechanisms from their replication-coupled canonical counterparts [28] [29]. Unlike canonical histones that are synthesized primarily during S-phase for DNA replication-coupled assembly, histone variants are typically expressed and incorporated into chromatin in a replication-independent manner throughout the cell cycle, allowing for continuous remodeling of the epigenome [27] [29].

The strategic incorporation of specific histone variants endows chromatin with unique structural and functional properties, creating distinct epigenetic landscapes that influence gene expression, DNA repair, and chromosome segregation [28] [30]. This review focuses on the pivotal roles of three principal histone variants—H3.3, H2A.Z, and macroH2A—in directing cell fate decisions. These variants operate as key epigenetic regulators in processes of cellular plasticity, including the maintenance of pluripotency in stem cells, the reversion to a less differentiated state (dedifferentiation), and the direct conversion of one differentiated cell type into another (transdifferentiation) [28] [2]. By modulating chromatin dynamics, these variants create permissive or restrictive environments for the transcriptional programs that define cellular identity, positioning them as critical players in development, disease, and regenerative medicine.

Core Histone Variants and Their Chaperone Systems

Key Histone Variants in Cell Fate Determination

Table 1: Major Core Histone Variants and Their Functions in Cell Fate

| Histone Variant | Genes | Key Chaperones/Remodelers | Primary Functions in Chromatin | Role in Cell Fate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3.3 | H3F3A, H3F3B | HIRA, DAXX/ATRX [31] [32] | Transcriptional activation, heterochromatin organization, telomere maintenance [28] [31] | Resets epigenetic state in reprogramming; enriched in pluripotent stem cells [28] [2] |

| H2A.Z | H2AFZ, H2AFV | SRCAP/p400 (deposition); INO80, ANP32E (eviction) [29] [14] | Transcriptional regulation (activation/repression), genome stability, anti-silencing [28] [14] | Modulates plasticity; regulates promoters/enhancers in stem cells [28] [2] |

| macroH2A | MACROH2A1, MACROH2A2 | FACT (eviction); ATRX (antagonizes deposition) [29] | Gene silencing, X-chromosome inactivation, higher-order chromatin compaction [28] [29] | Barrier to reprogramming; stabilizes differentiated state [28] |

| CENP-A | CENPA | HJURP [29] [32] | Centromere identity, kinetochore assembly, chromosome segregation [29] | Ensures genomic integrity during cell divisions in development [29] |

| H2A.X | H2AFX | FACT [29] | DNA damage response, marker of double-strand breaks (γH2AX) [2] [29] | Maintains genomic stability during fate changes [2] |

Chaperone-Mediated Deposition and Removal

The specific genomic localization and function of histone variants are largely governed by dedicated chaperone complexes and ATP-dependent chromatin remodelers [28] [29]. These machineries ensure the precise incorporation and removal of variants at specific genomic loci.

H3.3 Chaperones: The deposition of H3.3 is facilitated by two major, distinct complexes. The HIRA complex is responsible for H3.3 incorporation at active genes and regulatory elements, and it can be recruited by transcription factors to facilitate locus-specific deposition [31] [32]. In contrast, the ATRX-DAXX complex directs H3.3 to heterochromatic regions, including telomeres and pericentric repeats, where it contributes to the silencing of repetitive elements and the maintenance of genomic integrity, particularly in embryonic stem cells [28] [31].

H2A.Z Chaperones: The deposition of H2A.Z is primarily mediated by the SRCAP and p400 (also known as EP400) remodeling complexes [29] [14]. Conversely, the eviction of H2A.Z is facilitated by the INO80 remodeler and the histone chaperone ANP32E, which specifically recognizes H2A.Z and promotes its removal from chromatin [28] [29]. This dynamic turnover is crucial for its function in transcriptional regulation.

macroH2A Chaperones: While the deposition machinery for macroH2A is less defined, the FACT complex has been implicated in its eviction from chromatin, which is a necessary step for somatic cell reprogramming [29]. Furthermore, ATRX has been shown to antagonize macroH2A deposition, creating a regulatory interplay between different variant systems [28].

Figure 1: Histone Variant Chaperone Networks. Specialized chaperone complexes govern the deposition and removal of major histone variants, directing them to specific genomic locations to modulate chromatin function. ANP32E/INO80 is indicated as an eviction complex for H2A.Z.

Histone Variant Dynamics in Cell Fate Transitions

Maintaining Pluripotency in Embryonic Stem Cells

The unique chromatin landscape of embryonic stem cells (ESCs) is characterized by a hyperdynamic and open architecture, which facilitates access to a broad developmental gene repertoire. Histone variants are instrumental in establishing and maintaining this plastic state.

H3.3 in Pluripotency: H3.3 is highly abundant in ESCs and is enriched at both active gene promoters and repressed developmental genes marked by bivalent domains (possessing both active H3K4me3 and repressive H3K27me3 marks) [31] [32]. This positioning keeps these genes in a "poised" state for rapid activation upon differentiation. Furthermore, H3.3, deposited by the ATRX-DAXX complex, is essential for the silencing of endogenous retroviral elements and the maintenance of telomere integrity in ESCs, preventing deleterious activation of repetitive elements and ensuring genomic stability during rapid cell divisions [28].

H2A.Z in Pluripotency: H2A.Z is found at the promoters of many key pluripotency factors, such as OCT4 and NANOG [28] [14]. Its incorporation at these promoters, often in conjunction with H3.3, is thought to create a nucleosome structure that is inherently less stable and more easily displaced or remodeled. This facilitates the high transcriptional activity required for the self-renewing state and allows for rapid transcriptional changes upon receipt of differentiation signals [31] [14].

macroH2A as a Barrier: In contrast to H3.3 and H2A.Z, the macroH2A variant is generally lowly expressed in ESCs and acts as a stabilizer of the differentiated state. Its presence in somatic cell chromatin is a significant barrier to reprogramming, and its downregulation is often required for efficient reversion to a pluripotent state [28].

Driving and Stabilizing Differentiation

As ESCs exit the pluripotent state and commit to specific lineages, the chromatin landscape undergoes extensive reorganization. Histone variants contribute to this process by stabilizing new transcriptional programs and silencing pluripotency networks.

macroH2A-Mediated Silencing: The upregulation of macroH2A variants during differentiation contributes to the stable silencing of pluripotency genes [28]. MacroH2A-containing nucleosomes are particularly resistant to remodeling. They can directly hinder the binding of transcription factors like NF-κB to their target sites and block the activity of chromatin remodelers like SWI/SNF, thereby reinforcing gene repression and locking in the differentiated phenotype [2].

H2A.Z in Lineage-Specific Transcription: The role of H2A.Z in differentiated cells becomes highly context-dependent. It can contribute to both the activation and repression of lineage-specific genes. Its dynamic turnover at enhancers and promoters, regulated by the opposing actions of the SRCAP/p400 (deposition) and INO80/ANP32E (eviction) complexes, allows the cell to fine-tune transcriptional outputs in response to developmental cues [28] [14].

Enabling Dedifferentiation and Transdifferentiation

Cell fate is not a one-way street. Somatic cells can be reprogrammed to pluripotency (dedifferentiation) or directly converted into another somatic cell type (transdifferentiation). These processes require massive epigenetic rewiring, in which histone variants are key players.

H3.3 in Reprogramming: During the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), H3.3 is incorporated at loci critical for regaining pluripotency. It is believed to act as a pioneer factor that helps open the chromatin structure of somatic genes, facilitating their silencing, and at the same time, promoting the activation of the pluripotency network [2]. The HIRA chaperone complex is essential for this H3.3-dependent remodeling during reprogramming.

H2A.Z and Plasticity: The dynamic exchange of H2A.Z is crucial for the cellular response to reprogramming factors. Its presence at promoters creates a state of epigenetic plasticity that makes genes more responsive to external signals, a property that is exploited during both dedifferentiation and transdifferentiation protocols [2].

Inflammation as a Modulator: Inflammatory signaling can influence cell fate transitions by modulating the expression and incorporation of histone variants. For instance, the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β has been shown to promote β-cell dedifferentiation [2]. Furthermore, in senescent cells, the accumulation of the H2A.J variant drives the expression of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), a pro-inflammatory secretome that can alter the differentiation status of neighboring cells [2].

Table 2: Histone Variant Roles in Cell Fate Transitions

| Cell Fate Process | H3.3 Function | H2A.Z Function | macroH2A Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pluripotency Maintenance | Poises bivalent developmental genes; maintains telomere integrity [28] [31] | Destabilizes nucleosomes at pluripotency gene promoters [28] [14] | Low expression; acts as a barrier to acquisition of pluripotency [28] |

| Lineage Commitment | Turnover at enhancers/promoters facilitates activation of new gene programs [31] | Dynamic exchange fine-tunes expression of lineage-specific genes [28] | Upregulated; stabilizes differentiation by silencing pluripotency genes [28] [2] |

| Dedifferentiation/Reprogramming | Pioneer role in resetting epigenome; deposited by HIRA at key loci [2] | Promotes epigenetic plasticity and response to reprogramming factors [2] | Major barrier; must be evicted (e.g., by FACT) for efficient reprogramming [28] [29] |

| Transdifferentiation | Facilitates chromatin opening for new cell identity [2] | Enables shift in transcriptional networks [2] | Its downregulation may be permissive for fate switch [2] |

Experimental Approaches: Probing Histone Variant Function

Studying the intricate roles of histone variants requires a multifaceted methodological arsenal. The following section outlines key experimental protocols and reagents used to dissect the mechanisms of histone variant biology.

Key Methodologies

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing (ChIP-seq)

- Purpose: To map the genome-wide distribution of a specific histone variant or its associated post-translational modifications.

- Detailed Protocol: Cells are cross-linked with formaldehyde to preserve protein-DNA interactions. Chromatin is then isolated and sheared by sonication to fragments of 200-500 bp. An antibody specific to the histone variant (e.g., anti-H3.3, anti-H2A.Z) is used to immunoprecipitate the variant and its bound DNA. After cross-link reversal and DNA purification, the immunoprecipitated DNA is used to construct a sequencing library. The resulting data reveals peaks of variant enrichment across the genome, which can be correlated with genomic features like promoters, enhancers, and gene bodies [31].

- Key Controls: Isotype control IgG for non-specific binding, and an input DNA sample (sonicated chromatin prior to IP) for normalization.

Time-Course ChIP during Cell Fate Transitions

- Purpose: To capture the dynamic incorporation or removal of a histone variant during a process like differentiation or reprogramming.

- Application: As demonstrated in studies of retinoid acid-induced gene activation, time-course ChIP for H3.3 can reveal that its incorporation at enhancers occurs prior to gene induction, while its deposition at promoters is concomitant with activation, providing causal insight into its role [31].

Knockdown/Knockout of Variants or Chaperones

- Purpose: To determine the functional necessity of a specific histone variant or its deposition machinery.

- Methodology: Using RNAi (knockdown) or CRISPR-Cas9 (knockout) to deplete the target protein (e.g., HIRA, DAXX, or the H3.3 gene itself).

- Downstream Analysis: Phenotypic assessment (e.g., impact on reprogramming efficiency), transcriptomic analysis (RNA-seq) to identify misregulated genes, and ChIP-seq to examine changes in chromatin landscape and the localization of other variants [2] [31].

Biophysical Analysis of Nucleosome Stability

- Purpose: To understand how a variant's primary sequence directly affects nucleosome structure and dynamics.

- Methodology: Recombinant histone octamers containing the variant are assembled with defined DNA sequences to form mononucleosomes or chromatin arrays in vitro. Techniques such as FRAP (Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching) can measure protein mobility in live cells, while MNase-seq can assess nucleosome positioning and stability in situ. For example, in vitro studies have shown that H3.3 incorporation impairs higher-order chromatin folding without significantly affecting mononucleosome stability [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Histone Variant Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Specific Example | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Specific Antibodies | Anti-H3.3 (e.g., recognizing S31 residue); Anti-H2A.Z; Anti-macroH2A [31] | Immunodetection for ChIP-seq, Western Blot, and Immunofluorescence to determine localization and abundance. |

| Chaperone Mutants | HIRA-deficient cells; DAXX/ATRX knockout cells [28] [31] | To disrupt specific deposition pathways and dissect the function of variant localization. |

| Stable Cell Lines | Inducible shRNA against H2A.Z; Doxycycline-inducible H3.3 overexpression [2] | Allows for controlled manipulation of variant levels to study temporal effects on cell fate. |

| In Vitro Reconstitution Systems | Recombinant H3.3-H4 tetramers; H2A.Z-H2B dimers [31] | For biophysical studies of nucleosome stability, chromatin folding, and histone chaperone binding assays. |

| Biotinylated Nucleosomes | Nucleosomes containing biotin-tagged H2A.Z [14] | Used in pull-down assays to identify novel interacting proteins and remodeling complexes. |

| Mmp inhibitor II | Mmp inhibitor II, CAS:203915-59-7, MF:C21H27N3O8S2, MW:513.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| A-803467 | A-803467, CAS:944261-74-9, MF:C19H16ClNO4, MW:357.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Pathological Implications and Therapeutic Outlook

The deregulation of histone variant systems is increasingly implicated in human disease, particularly in cancer and developmental disorders. Their role as drivers of epigenetic plasticity makes them potent factors in disease pathogenesis.