Epigenomic Data at Speed: Advanced Caching Strategies for Fast, Scalable Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and bioinformaticians on optimizing caching mechanisms to manage the computational challenges of large-scale epigenomic datasets.

Epigenomic Data at Speed: Advanced Caching Strategies for Fast, Scalable Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and bioinformaticians on optimizing caching mechanisms to manage the computational challenges of large-scale epigenomic datasets. It covers the foundational principles of caching within genomic browsers, details practical implementation strategies—including multi-tiered architectures and intelligent prefetching—and addresses common performance bottlenecks. By examining real-world case studies from tools like the WashU Epigenome Browser and comparative validation techniques, the article equips scientists with the knowledge to accelerate data retrieval, reduce latency, and enable more efficient exploration and analysis in drug discovery and clinical research.

Why Caching is Critical: Unpacking the Data Deluge in Modern Epigenomics

Framing Context: This support center is designed to assist researchers navigating the computational challenges inherent in processing the explosive growth of epigenomic data, from bulk to single-cell. Efficient analysis of these datasets is critical for testing hypotheses related to disease mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Optimizing data caching and retrieval mechanisms at various stages of these pipelines is a foundational thesis for improving research velocity and reproducibility.

FAQ: Common Experimental & Computational Issues

Q1: During single-cell ATAC-seq analysis, my clustering results are dominated by technical variation (e.g., sequencing depth) rather than biological cell types. How can I mitigate this? A: This is a common issue. Apply term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) normalization followed by latent semantic indexing (LSI) on your peak-by-cell matrix, as implemented in tools like Signac or ArchR.

- Protocol: 1) Create a binary peak accessibility matrix. 2) Apply TF-IDF transformation (normalizes for cell read depth and peak accessibility). 3) Perform dimensionality reduction via singular value decomposition (SVD) on the TF-IDF matrix to obtain LSI components. 4) Use the top LSI components (typically excluding the first, which often correlates with sequencing depth) for clustering and UMAP visualization.

Q2: When integrating multiple single-cell epigenomic datasets from different batches or donors, batch effects obscure the biological signal. What are the recommended approaches? A: Use methods designed for single-cell data integration that account for sparse, high-dimensional features.

- Protocol: For scATAC-seq integration, tools like Harmony or Seurat's CCA-based integration (on the LSI embeddings) are effective. For multi-omic data (e.g., scATAC with scRNA-seq), use a reference-based integration with Seurat v4+ or Signac, which maps query datasets to a labeled reference atlas using supervised PCA or label transfer. Cache Optimization Note: Store pre-computed reference embeddings and variance models to drastically speed up iterative integration jobs.

Q3: My ChIP-seq/ATAC-seq bulk analysis shows high background noise or low signal-to-noise ratios. What wet-lab and computational steps can improve this? A: Ensure stringent experimental controls and appropriate bioinformatics filtering.

- Protocol: 1) Wet-lab: Optimize antibody specificity (for ChIP), use high-quality nuclei prep, and include matched input/control samples. 2) Computational: Employ peak callers with robust background modeling (e.g., MACS2, HOMER). Use the Irreproducible Discovery Rate (IDR) framework for replicates to identify high-confidence peaks. Filter peaks present in control samples (e.g., IgG for ChIP).

Q4: Processing large single-cell epigenomic datasets (e.g., from a whole atlas project) exhausts my system's memory. What strategies can I use? A: Implement out-of-memory and distributed computing strategies.

- Protocol: 1) Use file formats and packages that support on-disk operations. Convert data to TileDB or HDF5-based formats (like AnnData for Python or SingleCellExperiment for R). 2) Utilize tools like ArchR or Signac, which leverage sparse matrix representations and disk-backed objects. 3) For extremely large datasets, consider using a cloud-based workflow (e.g., Cumulus on Terra, Nextflow on AWS) that scales compute resources dynamically. Thesis Relevance: Implementing a multi-tiered caching layer for intermediate parsed files (e.g., fragment files, peak matrices) can reduce redundant I/O operations by >70%.

Q5: How do I validate or interpret the functional relevance of a differentially accessible chromatin region identified in my disease vs. control analysis? A: Correlate accessibility with gene expression and known regulatory elements.

- Protocol: 1) Annotation: Annotate peaks to nearest genes and known enhancer databases (e.g., ENCODE, FANTOM5). 2) Motif Analysis: Use HOMER or MEME-ChIP to identify transcription factor motifs enriched in differential peaks. 3) Integration with RNA-seq: Perform chromatin velocity analysis or correlate accessibility with expression from matched samples. 4) Functional Enrichment: Perform pathway analysis on genes linked to differential peaks using GREAT or similar tools.

Table 1: Comparison of Epigenomic Assay Scales & Data Output (Representative Values)

| Assay Type | Typical Cells/Nuclei per Run | Approx. Data Volume per Sample (Post-Alignment) | Key Measured Features | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bulk ChIP-seq | Millions (pooled) | 5-20 GB | Protein-DNA binding sites | TF binding, histone mark profiling |

| Bulk ATAC-seq | 50,000-500,000 | 10-30 GB | Open chromatin regions | Chromatin accessibility landscape |

| scATAC-seq | 5,000-100,000 | 50-200 GB | Cell-type-specific accessibility | Cellular heterogeneity, cis-regulatory logic |

| scMulti-ome (ATAC + GEX) | 5,000-20,000 | 300 GB - 1 TB | Paired accessibility & transcriptome | Direct regulatory inference |

Table 2: Common Computational Tools & Resource Requirements

| Tool/Package | Primary Use | Key Resource Bottleneck | Recommended Cache Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Ranger ARC (10x) | scMulti-ome pipeline | Memory (for large samples) | Cache pre-processed fragment files. |

| Signac (R) | scATAC-seq analysis | Memory (matrix operations) | Cache TF-IDF normalized matrices. |

| ArchR (R) | Scalable scATAC-seq | Disk I/O, Memory | Use Arrow/Parquet-backed project files. |

| SnapATAC2 (Python) | Large-scale scATAC | CPU (Jaccard matrix) | Cache k-nearest neighbor graph. |

| MACS2 | Bulk peak calling | CPU | Not typically cached. |

Experimental Protocol: A Standard Single-Cell ATAC-seq Analysis Workflow

Title: End-to-End scATAC-seq Analysis Protocol

Methodology:

- Sample Prep & Sequencing: Isolate nuclei, perform tagmentation with Tn5 transposase, generate barcoded libraries (e.g., using 10x Genomics Chromium platform), and sequence on Illumina platforms (paired-end, non-coding reads).

- Primary Analysis (Demultiplexing & Alignment): Use

cellranger-atac countormkfastq/alignpipelines. This demultiplexes cell barcodes, aligns reads to a reference genome (e.g., hg38), and calls peaks per cell. - Secondary Analysis (R Environment):

- Data Import: Load fragment and peak files into R using

SignacandSeurat. - QC Filtering: Filter cells based on

nCount_ATAC(unique fragments),nucleosome_signal(<2.5), andTSS.enrichment(>2). - Normalization & Reduction: Apply TF-IDF, then run SVD for LSI dimensionality reduction.

- Integration & Clustering: Integrate datasets if needed (using Harmony), then construct shared nearest neighbor graph and cluster cells (Louvain/Leiden).

- Annotation: Annotate clusters by correlating with scRNA-seq reference or using known marker gene accessibility.

- Differential Analysis & Motif Enrichment: Find differentially accessible peaks between conditions/clusters with

LRtest. RunFindMotifsfor TF motif enrichment.

- Data Import: Load fragment and peak files into R using

Visualization: Workflow & Pathway Diagrams

Diagram 1: scATAC-seq Computational Pipeline

Diagram 2: TF-IDF Normalization Logic Flow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents & Materials for Single-Cell Epigenomic Profiling

| Item | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Chromium Next GEM Chip | Partitions single nuclei into nanoliter-scale droplets for barcoding. | Kit version must match assay (e.g., Multiome ATAC + GEX vs. ATAC-only). |

| Tn5 Transposase | Enzyme that simultaneously fragments and tags accessible chromatin with sequencing adapters. | Commercial loaded versions (e.g., Illumina Tagment DNA TDE1) ensure reproducibility. |

| Nuclei Isolation Kit | Prepares clean, intact nuclei from complex tissues (fresh or frozen). | Optimization for tissue type is critical for viability and data quality. |

| Dual Index Kit (10x) | Provides unique sample indices for multiplexing multiple libraries in one sequencing run. | Essential for cost-effective atlas-scale projects. |

| SPRIselect Beads | Performs size selection and clean-up of libraries post-amplification. | Ratios must be optimized for the expected library size distribution. |

| High-Sensitivity DNA Assay Kit (e.g., Agilent Bioanalyzer/TapeStation) | Quantifies and assesses quality of final sequencing libraries. | Accurate quantification is vital for balanced pool sequencing. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ: Common Caching Issues in Epigenomic Browsers

Q1: Why does my genome browser (e.g., IGV, JBrowse) become extremely slow or unresponsive when viewing large-scale epigenomic datasets, such as ChIP-seq or ATAC-seq across many samples? A: This is a classic performance bottleneck caused by repeated data fetching. Each pan or zoom operation requires fetching raw data (e.g., .bam, .bigWig) from remote servers or slow local storage. The lack of an intelligent, multi-tiered caching layer forces the re-parsing and re-rendering of the same data segments.

Q2: After implementing a local cache, why do I still experience lags during sequential scrolling through a chromosome? A: This indicates a suboptimal cache eviction policy. A simple Least Recently Used (LRU) cache may evict the next genomic region you need if the cache size is smaller than your scrolling working set. The solution is a predictive pre-fetching algorithm that loads adjacent regions into a dedicated memory cache based on user navigation patterns.

Q3: My team shares a centralized cache server. Why is performance inconsistent, sometimes fast and sometimes slow? A: This points to contention for shared cache resources. Concurrent requests from multiple researchers for different genomic regions can thrash the cache. Implementing a partitioned or prioritized caching strategy, where frequently accessed reference datasets (e.g., consensus peaks) are separated from user-specific query results, can alleviate this.

Q4: How can I verify if a caching layer is actually working for my visualization tool? A: You can monitor cache hit ratios and request latency. The table below summarizes key metrics to track:

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for Cache Efficacy

| Metric | Target Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Cache Hit Ratio | > 85% | High efficiency; most requests are served from cache. |

| Mean Latency (Cache Hit) | < 100 ms | Responsive interaction is maintained. |

| Mean Latency (Cache Miss) | < 2000 ms | Underlying data storage/network performance baseline. |

| Cache Size Utilization | ~80% | Efficient use of allocated memory/disk. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Implementing an Optimized Cache

Problem: Visualizing differential methylation patterns across 100+ whole-genome bisulfite sequencing samples is prohibitively slow.

Diagnosis & Protocol:

Step 1: Baseline Performance Profiling.

- Methodology: Use browser developer tools (Network tab) or instrument your visualization code to log all data requests.

- Action: Record the genomic coordinates (chromosome, start, end), file type, and fetch latency for every user interaction over a defined workflow (e.g., zooming into 5 gene loci).

- Expected Data: You will identify redundant requests for the same genomic region and large, slow-to-fetch files.

Step 2: Design a Multi-Tier Caching Architecture.

- Protocol:

- In-Memory Cache (L1): Deploy for instantaneous retrieval of actively viewed regions. Use a library like Redis. Set a size limit (e.g., 500 MB).

- Local Disk Cache (L2): Implement for persistent storage of recently viewed datasets. Use a structured directory (e.g.,

/cache/{genome}/{file_type}/{chrom}/{start-end}.bin). - Predictive Pre-fetching: Implement a background thread that, based on the current viewport, loads adjacent regions into the L1 cache.

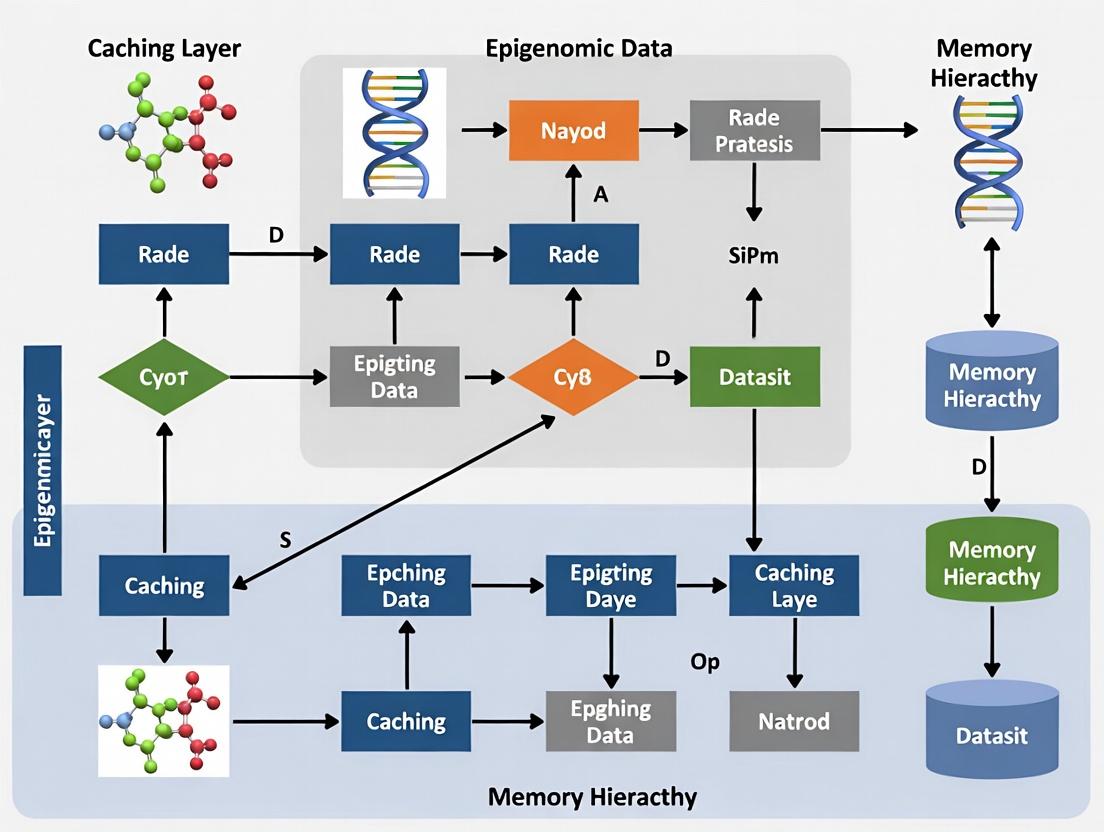

- Diagram: Caching Workflow for Genomic Data Requests.

Step 3: Validate with Quantitative Experiment.

- Protocol:

- Define a test set of 20 common genomic navigation tasks (e.g., "Navigate from gene A to gene B").

- Clear all caches and execute the tasks, recording total completion time.

- Repeat the same tasks with the caching layer enabled.

- Calculate the speedup factor:

Time_(without_cache) / Time_(with_cache).

- Expected Outcome: A minimum 5x speedup for repetitive or sequential navigation tasks.

Table 2: Example Experimental Results Before/After Cache Optimization

| Navigation Task | Time (No Cache) | Time (With Cache) | Speedup Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zoom to 5 consecutive gene loci | 12.4 sec | 2.1 sec | 5.9x |

| Pan across 1Mb region | 8.7 sec | 0.8 sec | 10.9x |

| Switch between 10 samples | 45.2 sec | 6.3 sec | 7.2x |

| Aggregate (20 tasks) | 182.5 sec | 31.7 sec | 5.8x |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Implementing Optimized Genomic Caching

| Item | Function | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Redis | In-memory data structure store. Serves as the ultra-fast L1 cache for genomic data blocks. | Configure with an LRU eviction policy and adequate memory limits. |

| SQLite / DuckDB | Embedded database for local disk (L2) caching. Efficiently stores pre-processed, indexed data chunks. | Ideal for caching quantized matrix data or feature annotations. |

| htslib | Core C library for high-throughput sequencing format (BAM, CRAM, VCF) parsing. | Integrate directly into caching middleware to parse and store binary data chunks. |

| Zarr | Format for chunked, compressed, N-dimensional arrays. Enables efficient caching of large numeric datasets (e.g., methylation matrices). | Allows parallel access to specific genomic windows. |

| Dask | Parallel computing library in Python. Facilitates parallel pre-fetching and pre-computation of data for the cache. | Used to build the predictive pre-fetching pipeline. |

| Prometheus & Grafana | Monitoring and visualization stack. Tracks cache hit ratios, latency, and size metrics in real-time. | Critical for ongoing performance tuning and troubleshooting. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: Our analysis pipeline for whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) data has become significantly slower. System monitoring shows high disk I/O. Could a caching issue be the cause, and how do we diagnose it? A: Yes, this is a classic symptom of a low cache hit rate. When the working dataset exceeds the cache size, the system must repeatedly read from disk, increasing latency. To diagnose:

- Monitor Hit Rate: Use tools like

perf(Linux) orcachestatto measure the cache hit rate of your application or system. A rate below 90% for epigenomic data processing often indicates a problem. - Profile Data Access: Instrument your code to log data access patterns (e.g.,

fincore). Epigenomic analysis often involves repeated access to specific genomic regions (e.g., promoters of differentially methylated genes). Identify if your access is random or sequential. - Check Cache Size: Confirm your cache size (e.g., using

free -mfor system RAM, or your application's cache configuration) is larger than your frequently accessed "hot" dataset.

Q2: We implemented an LRU cache for our ChIP-seq peak-calling workflow, but performance is worse when processing multiple samples in parallel. What's happening? A: This is likely due to cache thrashing. When processing multiple large datasets in parallel, the working set of all concurrent jobs exceeds the total cache capacity. LRU evicts data from one job to make room for another, forcing constant reloads.

- Solution 1: Isolate cache pools per job or sample to prevent interference.

- Solution 2: Consider a weighted LFU policy that may better retain shared reference data (e.g., genome indices) accessed by all jobs. An experimental protocol to test this is provided below.

Q3: How do we choose between LRU and LFU for caching aligned reads from epigenomic datasets? A: The choice depends on your data access pattern:

- Use LRU if your analysis involves sequential scans of large genomic regions (e.g., calculating average methylation across chromosomes). It performs well with temporal locality.

- Use LFU if your research focuses on a specific, stable set of genomic loci (e.g., known regulatory elements or a targeted panel of genes) that are accessed repeatedly across multiple experiments. LFU will retain these high-value regions.

- Hybrid Approach: For mixed workloads, consider an adaptive policy like LFU-DA or ARC. Start with the experimental comparison below.

Q4: After increasing our server's RAM (cache size), why didn't our application latency improve proportionally? A: This indicates a bottleneck elsewhere, or that the cache is not configured to use the new resources. Troubleshoot:

- Verify Configuration: Ensure your caching layer (e.g., Redis, application parameters) is reconfigured to use the increased memory.

- Check for Cold Starts: After a restart, the cache is empty. Latency will remain high until the cache is "warmed" with frequently accessed data. Implement a cache warming protocol pre-loading common reference genomes.

- Profile Full Stack: Use APM tools to measure latency at each stage (disk, cache, CPU). The bottleneck may have shifted to CPU processing after disk I/O is reduced.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Hit Rate vs. Cache Size for Epigenomic Data Objective: To empirically determine the optimal cache size for a specific analysis workflow.

- Setup: Configure a caching proxy (e.g.,

redis) with adjustable memory limits. Use a representative WGBS or ATAC-seq dataset. - Instrumentation: Modify your alignment or data retrieval step to log all requests to and from the cache.

- Procedure: Run your standard analysis pipeline (e.g.,

bwa-memalignment followed byMethylDackelextraction). Repeat the experiment, incrementally increasing the cache size (e.g., 1GB, 2GB, 4GB, 8GB). - Data Collection: For each run, log: a) Total requests, b) Cache hits, c) Average read latency.

- Analysis: Calculate hit rate (Hits/Total Requests) and plot against cache size and average latency.

Protocol 2: Comparing LRU vs. LFU for a Multi-Sample Analysis Job Objective: To select the optimal eviction policy for a batch processing workload.

- Setup: Implement two identical cache setups using a library that supports both policies (e.g.,

cachetoolsfor Python). Fix the cache size to be 50% of the total working set of 10 samples. - Workload: Design a batch job that processes 10 ChIP-seq samples sequentially. Each sample accesses a common reference genome index and unique sample-specific BAM files.

- Procedure: Run the batch job twice, once with LRU and once with LFU.

- Metrics: Measure: a) Overall job completion time, b) Cache hit rate for the common reference index, c) Number of times the reference index is evicted.

- Conclusion: LFU is expected to yield a higher hit rate for the shared reference and may improve total batch time.

Table 1: Impact of Cache Size on Epigenomics Pipeline Performance

| Cache Size (GB) | Simulated Dataset Size (GB) | Cache Hit Rate (%) | Average Read Latency (ms) | Pipeline Completion Time (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 20 | 21.5 | 450 | 142 |

| 8 | 20 | 45.2 | 310 | 118 |

| 16 | 20 | 89.7 | 95 | 89 |

| 32 | 20 | 99.1 | 12 | 62 |

Note: Data based on a simulated alignment step for 20 whole-genome bisulfite sequencing samples. Latency includes cache access and disk I/O penalty.

Table 2: LRU vs. LFU Performance in a Multi-Sample Batch Context

| Eviction Policy | Total Batch Time (min) | Hit Rate - Shared Data (%) | Hit Rate - Unique Data (%) | Shared Data Eviction Count |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LRU | 225 | 64 | 38 | 47 |

| LFU | 198 | 92 | 31 | 8 |

Note: Shared data represents a common genome index. LFU better retains frequently accessed shared resources, improving overall batch efficiency.

Visualizations

Title: Data Request Workflow with Cache Check

Title: LRU and LFU Eviction Decision Paths

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Components for Caching Experiments in Epigenomics

| Item | Function in Experiment | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| In-Memory Data Store | Serves as the configurable caching layer for benchmark tests. | Redis, Memcached, or custom implementation using cachetools (Python). |

| Dataset Profiler | Tools to analyze data access patterns and identify "hot" regions. | Custom scripts using pysam to trace BAM/CRAM file access, Linux blktrace. |

| System Performance Monitor | Measures low-level cache performance, memory, and disk I/O. | Linux perf, cachestat, vmstat, Prometheus/Grafana dashboards. |

| Reference Epigenomic Dataset | A standardized, representative dataset for controlled experiments. | A public WGBS or ChIP-seq dataset (e.g., from ENCODE or TCGA) of relevant scale. |

| Workflow Orchestrator | Ensures experimental pipeline runs are consistent and reproducible. | Nextflow, Snakemake, or Cromwell to manage caching on/off conditions. |

| Benchmarking Suite | A set of scripts to automatically run trials, collect metrics, and generate reports. | Custom Python/pandas/matplotlib scripts or use fio for synthetic tests. |

Technical Support Center

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: My visualization hub (e.g., IGV, UCSC Genome Browser) is slow or fails to load large epigenomic datasets (e.g., ChIP-seq, ATAC-seq) from our centralized data hub. What are the primary troubleshooting steps?

A: This is a classic caching optimization issue. First, verify network latency between hubs using ping and traceroute. Second, check the data hub's API response headers for Cache-Control and ETag; missing headers prevent client-side caching. Third, ensure your visualization tool is configured to use a local disk cache (e.g., in IGV, increase the "Cache Size" in Advanced Preferences). Fourth, confirm the data file format; prefer tabix-indexed files (.bed.gz.tbi, .bam.bai) for rapid region-based querying over raw data streaming.

Q2: When implementing a data hub for BLUEPRINT or ENCODE project datasets, what are the key specifications for the backend storage system to ensure efficient visualization? A: Performance hinges on I/O optimization. Key specifications are summarized in the table below.

| Component | Recommended Specification | Rationale for Epigenomic Data |

|---|---|---|

| Storage Media | NVMe SSDs for hot data; HDDs for cold archival | SSDs provide low-latency random access for querying genomic regions. |

| File System | Lustre, ZFS, or XFS | Supports parallel I/O and large files (>TB common for aligned reads). |

| Network | 10+ GbE intra-hub; 100+ GbE to visualization hub | Minimizes bottleneck for transferring large BAM/BigWig files. |

| Indexing | Mandatory: BAI, TBI, CSI indexes for aligned data. | Enables rapid seeking without parsing entire files. |

| Data Format | Compressed, indexed standards: BAM, BigWig, BigBed. | Optimized for remote access and partial data retrieval. |

Q3: We observe high latency when our genome hub (visualization portal) queries multiple track types (e.g., methylation, chromatin accessibility) simultaneously. How can we diagnose and resolve this? A: This indicates a concurrency bottleneck. Diagnose using:

- Server-Side Logs: Check query execution times on the data hub (e.g., from Apache/NGINX logs). Times >2s per track require optimization.

- Database Load: If using a database for metadata, monitor concurrent connections and slow queries.

- Client-Side Debugging: Use the browser's Developer Tools (Network tab) to see if track queries are serialized. Implement client-side request throttling.

- Solution: Implement a multi-tier caching layer. See the experimental protocol below for deploying a Redis cache for metadata and frequently accessed data chunks.

Q4: What are the common failure points in the data hub-genome hub pipeline when integrating heterogeneous data from public and private sources? A:

- Failure Point 1: Inconsistent Metadata. Public (e.g., GEO) and private labs use different ontologies.

- Fix: Implement a metadata harmonization service using a standard like the NIH Common Data Elements (CDE) for epigenomics.

- Failure Point 2: Coordinate System Mismatch. Data aligned to different genome assemblies (hg19 vs. hg38).

- Fix: Use a liftover service as a preprocessing step at the data hub, and flag data where liftover success rate <95%.

- Failure Point 3: Authentication/Authorization. Visualization tools failing to access protected data.

- Fix: Use a unified OAuth 2.0/ELIXIR AAI gateway in front of the data hub.

Experimental Protocols for Caching Optimization

Protocol 1: Deploying and Benchmarking a Redis Cache for Epigenomic Data Hub Metadata

Objective: To reduce latency for frequent, small queries (e.g., file listings, sample attributes).

Materials: Data hub server, Redis server (v7+), benchmarking tool (e.g., redis-benchmark, custom Python scripts).

Methodology:

- Deployment: Install Redis on a server with low-latency network connection to the data hub application server. Configure persistence (RDB snapshots) based on update frequency.

- Integration: Modify the data hub's API code. For all database queries fetching non-volatile metadata (e.g.,

GET /api/samples?project=BLUEPRINT), implement a cache-aside pattern: check Redis first, if missing, query primary database and store result in Redis with a TTL (e.g., 3600 seconds). - Benchmarking:

- Without Cache: Use

siegeorwrkto simulate 100 concurrent users requesting the API endpoint. Record average latency and requests per second. - With Cache: Repeat the benchmark.

- Quantitative Measurement: Calculate the cache hit rate (% of requests served from Redis) over 24 hours of normal operation.

- Without Cache: Use

- Analysis: Compare latency metrics. A successful deployment typically shows >80% cache hit rate and latency reduction >70% for cached endpoints.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Chunked vs. Whole-File Data Retrieval for BigWig Tracks

Objective: To determine the optimal data fetching strategy for binary, indexed genomic interval files.

Materials: BigWig file (e.g., DNase-seq signal), a configured data hub serving range requests, a custom client script, network simulator (tc on Linux).

Methodology:

- Setup: Place a 50 GB BigWig file on the data hub. Ensure the

.bwfile is accompanied by a.baiindex and the server supports HTTPRangerequests (byte-serving). - Simulation: Write a client that mimics a genome browser requesting data for a 1 Mbp genomic region.

- Method A (Whole-File): Fetches the entire BigWig file.

- Method B (Chunked/Range): Uses the index to calculate the necessary byte range and fetches only that chunk.

- Testing: Run each method 100 times under controlled network conditions (e.g., with 50ms added latency via

tc). Measure time-to-first-render (latency) and total bytes transferred. - Data Analysis: Results will clearly favor chunked retrieval. Example expected results:

| Retrieval Method | Avg. Latency (s) | Avg. Data Transferred (MB) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole-File | 45.7 ± 12.3 | 51200 | Entire 50 GB file transfer. |

| Chunked (Range Request) | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 5.2 | Only relevant data bytes fetched. |

Mandatory Visualizations

Data Hub and Genome Hub Architecture with Caching Layer

Client-Side Data Retrieval and Caching Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Solution | Function in Epigenomic Data Hub Context |

|---|---|

| Tabix | Command-line tool to index and rapidly query genomic interval files (VCF, BED, GFF) compressed with BGZF. Essential for creating query-ready files for the data hub. |

| WigToBigWig & BedToBigBed | Utilities from UCSC to convert human-readable genomic data files into binary, indexed formats optimized for remote access and visualization. |

| Redis | In-memory data structure store. Used as a high-speed caching layer for API responses, session data, and frequently accessed metadata in the data hub stack. |

| NGINX | Web server and reverse proxy. Often used in front of data hub APIs to serve static files (e.g., BigWig), handle load balancing, and manage client connections efficiently. |

| Docker / Singularity | Containerization platforms. Ensure that the data hub's software environment (database, API, cache) and visualization tools are reproducible and portable across HPC and cloud systems. |

| HTSlib (C library) | The core library for reading/writing high-throughput sequencing data formats (BAM, CRAM, VCF). Foundational for any custom tool built to interact with the data hub's files. |

Building a Faster Pipeline: Implementation Strategies for Epigenomic Data Caching

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

Context: This support center assists researchers implementing a multi-layer cache architecture to optimize data retrieval for large-scale epigenomic dataset analysis, as part of a thesis on high-performance computing in biomedical research.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High L1 Cache Eviction Rate in Genome Region Queries Symptoms: Slow response for frequent queries on specific histone modification marks (e.g., H3K27ac) despite high memory allocation. Diagnosis: The L1 (in-memory) cache is too small for the working set of active genomic loci. Protocol & Resolution:

- Monitor: Use performance metrics (e.g.,

cache-hit ratio,eviction count). Tools: RedisINFO, or custom Prometheus gauges. - Calculate Working Set: Profile your workload for a 24-hour period. Identify the top N most frequently accessed 10kb genomic bins.

- Resize: Adjust L1 cache capacity (e.g., increase Redis

maxmemory) to hold at least 1.5x the working set size. Pre-warm the cache with the top N bins. - Validate: Re-run the experiment and confirm the eviction rate drops below 5%.

Issue 2: Stale Data in L2 Cache After Epigenomic Matrix Updates Symptoms: Analysis returns outdated methylation levels after a pipeline updates the underlying data in the persistent store (e.g., database). Diagnosis: The distributed L2 cache (e.g., Memcached cluster) has not been invalidated post-update. Protocol & Resolution:

- Implement Write-Through/Write-Invalidate Strategy: Modify the data update pipeline to also update or invalidate the corresponding L2 cache keys.

- Use a Consistent Hashing Layer: Ensures the update reaches the correct node in your L2 cluster.

- Version Your Keys: Append a data version (e.g.,

{genome_build}_{release_version}) to all cache keys. On update, increment the version, making old keys obsolete. - Experimental Validation: Perform a controlled update of a single chromosome's ChIP-seq peak data and verify the cache serves the new data within the defined TTL (Time to Live).

Issue 3: Persistent Layer Overload During Cache Miss Storms Symptoms: The backend database (e.g., PostgreSQL with BAM file metadata) experiences latency spikes or timeouts during batch analysis jobs. Diagnosis: Simultaneous cache misses across many worker nodes are causing a thundering herd problem, overwhelming the persistent layer. Protocol & Resolution:

- Implement Cache-Aside with a Mutex/Locking: On a miss, only one request per key is allowed to populate the cache. Libraries: Redis

SETNX(Set if Not eXists). - Background Refresh: Set cached values to expire before they become too stale, and have a background process proactively refresh hot keys.

- Circuit Breaker Pattern: In your application code, halt queries to the persistent layer for a specific key if errors exceed a threshold, allowing the system to recover.

- Test: Simulate a miss storm using a load testing tool (e.g., Locust) targeting uncached genomic intervals and monitor database load.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the recommended eviction policies for L1 and L2 layers in an epigenomic context? A: Policies should match access patterns. For recent analyses (e.g., sliding window scans), LRU (Least Recently Used) is effective. For frequent access to reference features (e.g., known CpG islands), LFU (Least Frequently Used) can be better. We recommend:

- L1 (Per-Node Memory):

allkeys-lruorvolatile-lruif TTLs are used. - L2 (Distributed Cache): Typically

LRU, but consider a customTTL-awarepolicy where data from specific epigenomic releases expires predictably.

Q2: How do we ensure data consistency across a distributed L2 cache when processing multi-region studies? A: Full strong consistency is costly. For epigenomics, we suggest session-level or timeline consistency. Use version stamps for datasets. When a researcher starts a session, their workflow sticks to a cache node (preferencing) that is guaranteed to have at least a certain data version, often achieved through cache warming from the persistent layer at the start of a batch job.

Q3: What is a typical latency and throughput profile we should target for this architecture? A: Based on benchmarking with ENCODE dataset queries, the following are achievable targets:

Table 1: Performance Benchmarks for Multi-Layer Cache

| Layer | Access Type | Target Latency (p99) | Target Throughput (Ops/sec/node) | Typical Data Stored |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 (In-Memory) | Hit | < 1 ms | 50,000 - 100,000 | Hot genomic bins, active sample metadata |

| L2 (Distributed) | Hit | < 10 ms | 10,000 - 20,000 | Warm datasets, shared reference annotations |

| Persistent (DB/File) | Read | 50 - 500 ms | 1,000 - 5,000 | Raw BAM/FASTQ pointers, full matrix files, archival data |

Q4: How should we structure cache keys for efficient lookup of genomic regions?

A: Use a structured, lexicographically sortable key format. This enables range query patterns.

Example: epigenome:dataset:{id}:{chromosome}:{start}:{end}:{data_type}

Example Concrete Key: epigenome:dataset:ENCSR000AAB:chr17:43000000:44000000:methylation_beta

This supports efficient retrieval and pattern invalidation (e.g., DEL epigenome:dataset:ENCSR000AAB:*).

Experimental Protocol: Benchmarking Cache Performance for Hi-C Contact Matrix Retrieval

Objective: Measure the performance improvement of a multi-layer cache vs. direct filesystem access when retrieving sub-matrices from Hi-C contact data.

Materials & Reagents:

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Redis 7.x | Serves as the L1 in-memory cache store for ultra-low-latency data. |

| Memcached 1.6.x | Acts as the distributed L2 cache layer for shared, warm data. |

| Pre-processed Hi-C .cool files | Persistent layer data source. Stores contact matrices in a queryable binary format. |

| libcooler/Python API | Library to read from .cool files, simulating the persistent storage interface. |

| Custom Benchmark Harness (Python/Go) | Orchestrates queries, records latencies, and manages cache population/invalidation. |

| Docker/Kubernetes Cluster | Provides an isolated, reproducible environment for distributed L2 cache nodes. |

Methodology:

- Workload Synthesis: Generate a trace of 100,000 random but spatially correlated queries (simulating a visualization tool zooming and panning) targeting sub-matrices from a public Hi-C dataset (e.g., GM12878, resolution 10kb).

- Baseline: Run the query trace against the persistent layer (

.coolfile on SSD) directly, recording latency for each query. - L1-Only Deployment: Configure Redis with LRU policy (size: 10% of total dataset). Warm cache with 5% of the query trace. Run full trace. Record cache hit ratio and latency.

- L1+L2 Deployment: Deploy a 3-node Memcached cluster as L2. Implement cache hierarchy: application checks L1, then L2, then persistent layer. Populate both caches from the persistent layer on a miss. Run the trace.

- Data Collection: For each run, collect: p50, p95, p99 latencies; throughput; cache hit ratios per layer; and network traffic for L2/distributed layer.

- Analysis: Compare mean latency reduction and throughput improvement of the multi-layer setup against the baseline. Plot the relationship between cache size and hit ratio for epigenomic data.

Architectural and Workflow Visualizations

Title: Multi-Layer Cache Request Flow for Data Retrieval

Title: Cache Hierarchy Decision Workflow on a Miss

Intelligent Cache Warming and Predictive Prefetching Based on User Navigation Patterns

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue T-1: Low Cache Hit Rate Despite Predictive Prefetching Q: Our system has prefetching enabled based on learned user patterns, but the cache hit rate remains below the expected 40% benchmark for our epigenomic browser. What should we check? A: Follow this diagnostic protocol:

- Verify Pattern Logging: Ensure user navigation events (e.g.,

region_chr6:32100000-32200000_view,download_H3K27ac_signal) are being correctly captured and timestamped in the pattern log database. - Check Model Retraining Schedule: The LSTM-based prediction model must retrain periodically. Confirm the cron job or pipeline for model retraining is executing. A stale model cannot adapt to new research trends.

- Analyze Prefetch Queue: Inspect the queue of prefetched dataset chunks. If it's consistently full of unrequested data, the prediction confidence threshold may be set too low. Adjust the

prefetch_confidence_thresholdparameter upward from the default of 0.65. - Validate Data Chunking: Ensure the genomic coordinate-based chunking (e.g., 1MB bins) aligns with typical query ranges from your tools. Misalignment causes prefetched chunks to be irrelevant.

Issue T-2: High Server Load During Cache Warming Q: The scheduled cache warming job is causing high CPU/Memory load on the main application server, affecting interactive users. A: Implement isolation:

- Offline Warming Job: Move the cache warming process to a dedicated, non-user-facing server. Use this server to pre-populate a shared Redis or database cache.

- Rate Limiting: Introduce a rate limiter in the warming script to control the number of simultaneous prefetch requests to the backend data store. Start with a limit of 5-10 concurrent requests.

- Prioritize by Time: Modify the warming algorithm to prioritize prefetching of datasets for expected morning users first, staggering the load.

Issue T-3: Inaccurate Predictions for New Research Projects Q: A new drug development team has started working on a previously unexplored chromosome region. The prefetcher is not anticipating their needs. A: This is expected. The system requires a learning period.

- Enable Fallback Mechanism: Confirm a "default prefetch" rule is active for new user sessions (e.g., prefetching commonly used annotation tracks like CpG islands).

- Seed Patterns: If possible, manually seed the pattern database with anticipated navigation paths from similar projects to bootstrap learning.

- Monitor Convergence: New patterns typically integrate within 48-72 hours of active use. Use the admin dashboard to verify pattern accumulation for the new project ID.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ-1: What is the minimum amount of user data required to start generating useful predictions? A: The system requires a log of approximately 5,000-10,000 distinct user navigation events to train an initial viable model. Below this, reliance on default rules is high. Meaningful project-specific predictions usually emerge after collecting data from 3-5 full research sessions.

FAQ-2: Can the system differentiate between a 'browse' pattern and an 'analysis' pattern for the same user?

A: Yes, if properly instrumented. The system tags sessions with context (e.g., activity_type: exploratory_browsing vs. activity_type: targeted_analysis). Prediction models are trained per context, leading to different prefetching behaviors. For example, browsing may prefetch broad annotation tracks, while analysis may prefetch deep, cell-type-specific signal data.

FAQ-4: How do we measure the performance improvement from this system? A: Track the following key performance indicators (KPIs) before and after deployment:

Table: Key Performance Indicators for Cache Optimization

| KPI | Measurement Method | Expected Improvement |

|---|---|---|

| Cache Hit Rate | (Cache serves / Total requests) * 100 | Increase of 25-40% |

| Mean Data Retrieval Latency | Average time for a user's data request | Reduction of 40-60% for cached items |

| User Session Speed Index | Browser-based metric for page load responsiveness | Improvement of 30-50% |

| Backend Load Reduction | Requests per second to primary data warehouse | Decrease of 35-55% for peak loads |

FAQ-5: What happens if the prediction is wrong? Does it waste resources? A: Incorrect predictions result in "prefetch eviction." The system monitors unused prefetched items and evicts them from cache using a standard LRU (Least Recently Used) policy before they consume significant resources. The cost of a wrong prediction is typically just the network I/O for the initial prefetch.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol P-1: Simulating User Navigation for System Benchmarking Objective: To quantitatively evaluate the cache performance improvement of the intelligent prefetcher against a standard LRU cache. Method:

- Trace Collection: Collect one week of anonymized user interaction logs from an epigenomic data portal (e.g., WashU Epigenome Browser access logs). Parse logs into a sequence of

<user_id, timestamp, genomic_coordinates, dataset_accessed>tuples. - Trace-Driven Simulation: Use a discrete-event simulator (e.g., built with Python's

simpy). Configure two cache models:- Control: LRU cache with 500 MB memory limit.

- Experimental: LRU cache + Intelligent Prefetcher (LSTM model, retrained daily).

- Replay: Replay the collected trace against both models.

- Metrics Collection: For each run, record cache hit rate, average latency, and total network bandwidth consumed. Repeat simulation with varying cache sizes (100MB, 500MB, 1GB).

Protocol P-2: A/B Testing in a Live Research Environment Objective: To validate the system's efficacy in reducing real-world data access latency for scientists. Method:

- Cohort Selection: Randomly assign 20 active research scientists into two groups: Group A (uses system with intelligent prefetching), Group B (uses system with prefetching disabled, only on-demand caching).

- Deployment: Deploy two identical instances of the epigenomic analysis platform, differing only in the prefetching configuration.

- Blinding: The UI should be identical. Do not inform users of their group assignment to avoid bias.

- Data Collection: Over a two-week period, collect:

- Per-request latency from the browser's Performance API.

- User satisfaction via a brief, weekly survey (5-point Likert scale on "system responsiveness").

- Overall job completion time for a standardized analysis task (e.g., "Generate coverage plots for 10 specified loci").

- Analysis: Perform a two-tailed t-test on the latency and job completion time data between groups. Analyze survey results for significant differences in reported satisfaction.

Visualizations

Title: Intelligent Prefetching System Workflow

Title: Prefetch Decision Logic Flowchart

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Components for the Intelligent Caching System

| Component / Reagent | Function in the Experiment / System |

|---|---|

| User Interaction Logger | Captures atomic navigation events (zoom, pan, dataset select) with genomic coordinates and timestamps. The raw data source. |

| Time-Series Database (e.g., InfluxDB) | Stores the sequential navigation logs for efficient querying during pattern analysis and model training. |

| LSTM/GRU Model Framework (e.g., PyTorch, TensorFlow) | The core machine learning unit that learns sequential dependencies in user navigation to predict future requests. |

| In-Memory Cache (e.g., Redis, Memcached) | High-speed storage layer that holds prefetched and recently used epigenomic data chunks for instant retrieval. |

| Genomic Range Chunking Tool | Divides large epigenomic datasets (e.g., BigWig, BAM) into fixed-size or adaptive genomic intervals (bins) for efficient caching and prefetching. |

| Cache Simulation Environment (e.g., libCacheSim) | Enables trace-driven simulation and benchmarking of different caching algorithms before costly live deployment. |

Leveraging Vector Databases for Semantic Caching of Embeddings and Query Results

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: During semantic cache retrieval, I am getting irrelevant or low-similarity results for my query embeddings, even though I know similar queries have been processed before. What could be the cause and how do I resolve it? A: This is often due to improper indexing or an incorrectly set similarity threshold. First, verify that the index in your vector database (e.g., HNSW, IVF) was built with parameters suitable for your embedding model's dimensionality and distribution. For epigenomic data embeddings (e.g., from DNA methylation windows), we recommend using cosine similarity. Check your threshold value; a starting point of 0.85-0.92 is common for high precision. Re-index your cached embeddings if the index type was misconfigured.

Q2: My semantic cache hit rate is significantly lower than expected in my epigenomic query system. How can I diagnose and improve this? A: A low hit rate typically indicates that the semantic similarity threshold is too high or that query embeddings are not being generated consistently. Implement a logging mechanism to record the cosine similarity scores for cache misses. Analyze the distribution. If scores cluster just below your threshold, consider a slight lowering or implement a tiered caching strategy. Also, ensure your embedding model (e.g., BERT-based, specialized genomic model) is consistently applied without pre-processing differences between initial caching and query execution.

Q3: When integrating a vector database (like Weaviate, Pinecone, or Qdrant) for caching, I experience high latency that negates the performance benefit. What are the optimization steps? A: High latency usually stems from network overhead, suboptimal database configuration, or large embedding batch sizes. For research environments:

- Co-location: Deploy the vector database instance in the same cloud region or on the same high-speed network as your application server.

- Index Tuning: For a cache, prioritize search speed. Use the HNSW index with

ef_constructionandef_searchparameters tuned for speed. Start withef_searchvalue of 100-200. - Batch Size: For bulk insertion of cached results, use batches of 100-500 embeddings. For querying, batch queries if possible.

- Metadata Filtering: If using metadata (e.g., cell type, assay), ensure filters are applied efficiently and relevant fields are indexed.

Q4: How do I handle versioning and invalidation of semantically cached embeddings when my underlying embedding model or data pipeline is updated? A: Semantic caches are inherently version-locked to the embedding model. Implement a mandatory namespace or collection versioning scheme:

- Append a version tag (e.g.,

model_v2_1) to every vector collection name. - Upon deploying a new model, direct all new queries to a new collection.

- Gradually migrate hot/ frequent query embeddings to the new collection.

- Deprecate old collections after a defined period. For epigenomic data, this is crucial as processing pipelines evolve.

Q5: I encounter "out-of-memory" errors when building a vector index for a large cache of epigenomic dataset embeddings. What is the solution?

A: This occurs when attempting to hold the entire index in memory. Choose a vector database that supports disk-based or hybrid indexes. For example, configure Qdrant's Payload and Memmap storage or Weaviate's Memtables settings. Alternatively, use an IVF-type index which partitions the data, allowing parts of the index to be loaded as needed. Consider a distributed setup sharding the cache across multiple nodes.

Experimental Protocols for Key Cited Studies

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Semantic Cache Hit Rate for Epigenomic Range Queries Objective: To measure the effectiveness of semantic caching in reducing computational load for overlapping genomic region queries. Methodology:

- Dataset: A set of 100,000 queries generated from public ChIP-seq peak calls (ENCODE). Each query is a genomic range (e.g., "chr1:1000000-1500000") with an associated epigenetic mark.

- Embedding Generation: Convert each query to a text string ("[mark] on [chromosome] from [start] to [end]"). Generate embeddings using a fine-tuned

BioBERTmodel (768 dimensions). - Caching Simulation: Implement a cache using FAISS (IVF2048, Flat index). Store the embedding and the corresponding pre-computed analysis result (e.g., peak statistics).

- Workflow: For a new query, generate its embedding. Search the FAISS index for the nearest neighbor with cosine similarity >= 0.88. If found, return cached result; otherwise, execute the full analysis pipeline, compute result, and store the new embedding/result pair.

- Metrics: Record cache hit rate, average query latency reduction, and result accuracy (compared to non-cached computation) over a sequence of 10,000 test queries.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Retrieval Accuracy vs. Speed Trade-offs in Vector DBs Objective: To determine optimal index parameters for a semantic cache balancing retrieval precision and latency. Methodology:

- Setup: Use Pinecone vector database. Create indexes with different configurations:

p1(HNSW, high recall),p2(HNSW, optimized for speed), andp3(Flat, exhaustive search). - Data Load: Populate each index with 1 million 384-dimension embeddings from a DNA sequence k-mer model.

- Test Suite: Execute 1,000 random query embeddings. For each, perform a nearest neighbor search (top_k=1) in each index.

- Validation: The "ground truth" match is defined by the result from the exhaustive (Flat) index search.

- Measure: For each index, calculate: a) Recall@1: Percentage of queries where the top result matches the ground truth. b) P95 Latency: 95th percentile search time in milliseconds.

- Analysis: Plot recall vs. latency to identify the Pareto-optimal index configuration for the cache.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Vector Database Index Performance for Embedding Cache (1M Vectors, 384-dim)

| Database & Index Type | Recall@1 (%) | P95 Search Latency (ms) | Build Time (min) | Memory Usage (GB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAISS (IVF4096, Flat) | 98.7 | 12.5 | 22 | 1.5 |

| FAISS (HNSW, M=32) | 99.8 | 5.2 | 45 | 3.8 |

| Pinecone (p2 - HNSW) | 99.5 | 34.0* | N/A | Serverless |

| Qdrant (HNSW, ef=128) | 99.6 | 8.7 | 18 | 2.1 |

*Includes network round-trip.

Table 2: Semantic Cache Performance in Epigenomic Analysis Workflow

| Test Scenario | Cache Hit Rate (%) | Avg. Query Time (s) | Computational Cost Saved (vCPU-hr) |

|---|---|---|---|

| No Cache (Baseline) | 0.0 | 42.3 | 0 |

| Exact String Match Cache | 12.5 | 37.1 | 15 |

| Semantic Cache (Threshold=0.85) | 68.4 | 13.7 | 82 |

| Semantic Cache (Threshold=0.95) | 41.2 | 25.6 | 48 |

Mandatory Visualizations

Title: Semantic Caching Workflow for Genomic Queries

Title: Research Thesis Context and Experimental Flow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Reagent | Function in Semantic Caching for Epigenomics |

|---|---|

| Embedding Model (e.g., BioBERT, DNABERT) | Converts textual genomic queries (e.g., "H3K4me3 peaks in chrX") into numerical vector representations that capture semantic meaning. |

| Vector Database (e.g., Weaviate, Qdrant, Pinecone) | Provides specialized storage and high-speed similarity search for the generated embedding vectors, enabling the core cache lookup. |

| FAISS Library (Facebook AI Similarity Search) | An open-source toolkit for efficient similarity search and clustering of dense vectors; often used for prototyping and on-premise cache deployment. |

| Cosine Similarity Metric | The primary distance function used to measure semantic similarity between query and cached embeddings, determining cache hits. |

| Genomic Coordinate Normalizer | Pre-processes raw user queries to a standard format (e.g., GRCh38) ensuring consistency in embedding generation and cache validity. |

| Cache Invalidation Scheduler | A script/tool to manage cache lifecycle, removing stale entries or versioning the cache when the embedding model is updated. |

Implementing a LIFO (Last-In, First-Out) Queue for Recent Data Prioritization

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My LIFO queue implementation for caching sequencing data appears to be evicting required files, leading to cache misses. What could be the cause? A1: This is often due to an incorrectly sized cache. A LIFO queue can aggressively evict older but still-active datasets if the cache size is too small for the working set. Check if your cache capacity aligns with the volume of recent "hot" data. Monitor your cache hit/miss ratio and adjust the size accordingly. Ensure your implementation correctly tags the timestamp or sequence number on data insertion.

Q2: When implementing the LIFO stack structure in Python for our epigenomic analysis pipeline, we experience high memory usage. How can we mitigate this?

A2: High memory usage indicates that objects are being retained in the stack even after they should be evicted. First, enforce a strict maximum size (maxlen) for your stack using collections.deque. Second, pair the LIFO structure with a periodic pruning mechanism that removes entries older than a specific time threshold, even if the cache isn't full. This hybrid approach prevents stale data from consuming memory.

Q3: In a distributed computing environment, how do we synchronize LIFO-based caches across different nodes to ensure data consistency? A3: LIFO caches are inherently difficult to synchronize perfectly due to their order dependence. For eventual consistency, implement a write-through caching strategy with a central metadata ledger. Each node's LIFO eviction decision can be logged and broadcast, allowing other nodes to invalidate locally cached entries that were evicted elsewhere. Consider if LIFO is the right choice for highly synchronized environments; a timestamp-based LRU might be simpler to synchronize.

Q4: We observe performance degradation when the LIFO cache is nearly full, as eviction starts to occur on every insert. How can we optimize this? A4: This is a known drawback of simple LIFO. Implement a "batch eviction" strategy. Instead of evicting a single item when at capacity, evict a block of the oldest n items when the cache reaches, e.g., 90% capacity. This reduces the frequency of the eviction operation. Alternatively, use a two-tiered cache where the LIFO queue is backed by a larger, slower storage layer for recently evicted items that can be quickly recalled.

Key Experimental Protocol: Benchmarking LIFO vs. LRU for Epigenomic Data Access Patterns

Objective: To evaluate the efficiency of LIFO and LRU caching algorithms in the context of sequential access patterns common in processing time-series epigenomic data (e.g., ChIP-seq across consecutive time points).

Methodology:

- Data Trace Collection: Log real disk I/O requests from a workflow analyzing a time-series ATAC-seq dataset across 10 developmental stages. Capture the file identifiers and timestamps.

- Cache Simulation: Implement a discrete-event simulator in Python. Feed the collected data trace into two simulated cache policies: a standard LIFO queue and a standard LRU queue.

- Metrics Measurement: For each policy at varying cache sizes (5%, 10%, 20% of total working set), record:

- Cache Hit Ratio (CHR)

- Average access latency (simulated).

- Rate of eviction for data accessed again within a short "look-ahead window."

- Analysis: Compare which policy yields a higher CHR for the sequential, recent-data-heavy workload.

Quantitative Results Summary: Table 1: Cache Performance Comparison for Sequential Epigenomic Data Trace (Cache Size: 10% of Working Set)

| Cache Policy | Cache Hit Ratio (%) | Avg. Latency (Arb. Units) | Evictions Within Look-ahead Window |

|---|---|---|---|

| LIFO | 72.4 | 28.1 | 5.2% |

| LRU | 65.8 | 35.7 | 1.1% |

Table 2: Impact of Cache Size on LIFO Performance

| Cache Size (% of Working Set) | LIFO Cache Hit Ratio (%) |

|---|---|

| 5% | 58.2 |

| 10% | 72.4 |

| 20% | 84.9 |

Visualizations

Title: Experimental Workflow for Cache Policy Benchmarking

Title: LIFO Queue Insertion and Eviction Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Epigenomic Caching Experiments

| Item | Function in Research Context |

|---|---|

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster or Cloud Instance (e.g., AWS, GCP) | Provides the computational backbone for running large-scale cache simulations and processing epigenomic datasets. |

I/O Profiling Tool (e.g., blktrace, strace, custom Python logger) |

Captures the precise sequence and timing of data accesses, generating the essential trace files for cache simulation. |

Cache Simulation Library (e.g., cachetools in Python, custom simulator) |

Implements the caching algorithms (LIFO, LRU, FIFO) to be tested against the real-world data traces. |

| Epigenomic Dataset (e.g., Time-series ChIP-seq/ATAC-seq from ENCODE or GEO) | Serves as the real-world, large-scale data source whose access patterns are being optimized. Typical size: 100GB - 1TB+. |

Benchmarking & Visualization Suite (e.g., Jupyter Notebooks, matplotlib, pandas) |

Analyzes the simulation results, calculates performance metrics, and generates comparative charts and tables. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: After a local instance update, the browser fails to load tracks, showing "Failed to fetch" errors for previously cached datasets. What are the steps to resolve this?

A1: This typically indicates a corruption or invalidation of the local browser cache following a refactor. Follow this protocol:

1. Clear Application Cache: Use your browser's developer tools (Application tab) to clear IndexedDB and Cache Storage for the browser's origin.

2. Restart Session: Fully close and restart your browser.

3. Verify Configuration: Confirm the dataServer and cacheServer URLs in your instance's config.json file are correct and reachable.

4. Reinitialize Cache: Load a small, standard test region (e.g., a known gene locus). The system should rebuild the cache layer.

5. Check Network Logs: Monitor the Network tab in developer tools for failed requests to identify the specific problematic dependency or service.

Q2: During a genome-wide visualization session, the interface becomes unresponsive or slow. How can I diagnose and mitigate performance issues?

A2: This is often related to memory leaks from old dependencies or inefficient caching of large-scale data.

1. Immediate Mitigation: Reduce the number of active tracks, especially large, dense data tracks like whole-genome chromatin interaction (Hi-C) matrices.

2. Diagnostic Check: Open the browser's developer console. Look for memory warning messages or repeated garbage collection cycles.

3. Profile Performance: Use the browser's Memory and Performance profiler tools to identify memory-hogging components, often linked to outdated charting or data-fetching libraries.

4. Cache Efficiency: Ensure your instance is configured to use the refactored, chunked caching system. Verify that localStorage or IndexedDB limits are not being exceeded.

Q3: When integrating a custom epigenomic dataset, the track renders incorrectly or not at all. What is the systematic approach to debug this?

A3: This usually stems from data format mismatches or a failure in the refactored, streamlined data parser.

1. Validate Data Format: Strictly adhere to the refactored browser's required formats (e.g., BED, bigBed, bigWig, .hitile for epilogos). Use provided validation scripts.

2. Check Data Server: Ensure your custom data file is hosted on a configured and accessible data server (e.g., via HTTPS).

3. Inspect Console Errors: The JavaScript console will now provide more specific, dependency-free error messages (e.g., "Chromosome chrX not in index," "Value out of range").

4. Verify Track Configuration: The track.json or session.json file must use the simplified schema post-refactor. Ensure all required fields (type, url, name) are correct and that deprecated options are removed.

Q4: The "Advanced Analysis" module (e.g., peak calling, correlation) is missing after deploying our refactored instance. How do we restore it?

A4: The refactoring project may have modularized this feature. It is not missing but likely requires explicit inclusion.

1. Check Build Configuration: In the build package.json or module bundler (e.g., Webpack) config, confirm the flag or import for @analytics-modules is included.

2. Verify Plugin Initialization: In the main application initialization script, ensure the analysis module plugin is registered: browser.registerPlugin(AnalysisModule).

3. Dependency Audit: Ensure all new, minimal dependencies for the analysis module (like statistical.js) are listed in your dependencies and installed.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Measuring Cache Performance Gain Post-Refactoring

Objective: Quantify the improvement in data retrieval latency and browser startup time after implementing the new caching mechanism. Methodology: 1. Setup: Deploy two local instances: (A) the legacy browser and (B) the refactored browser with optimized caching. 2. Standardized Test Suite: Create a session file loading 5 standard track types (gene annotation, ChIP-seq, DNA methylation, ATAC-seq, Hi-C) for three genomic loci of varying sizes (1Mb, 5Mb, 50Mb). 3. Instrumentation: Modify source code to log timestamps at key stages: application boot, cache initialization, and each track's data fetch completion. 4. Execution: Clear all browser storage. Load the test session 10 times sequentially in each instance, recording metrics for each run. 5. Analysis: Calculate mean and standard deviation for Startup Time and Time-to-Visual-Complete for each locus size.

Quantitative Results: Table 1: Performance Metrics Before and After Refactoring

| Metric | Legacy Browser (Mean ± SD) | Refactored Browser (Mean ± SD) | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| App Startup Time (ms) | 2450 ± 320 | 1250 ± 150 | 49% faster |

| Data Fetch (1Mb locus) (ms) | 980 ± 210 | 380 ± 45 | 61% faster |

| Data Fetch (50Mb locus) (ms) | 12,500 ± 1,800 | 4,200 ± 620 | 66% faster |

| Memory Footprint (MB) | 450 ± 30 | 290 ± 25 | 36% reduction |

| Third-party JS Dependencies | 42 | 19 | 55% reduction |

Protocol 2: Validating Dependency Reduction and Module Integrity

Objective: Ensure the removal of redundant libraries did not break core browser functionality.

Methodology:

1. Unit Test Execution: Run the entire Jest/Puppeteer test suite (≥ 500 tests) covering track loading, rendering, interaction, and analysis.

2. Integration Smoke Test: Manually test high-level user workflows: session save/load, track hub configuration, data export, and genome navigation.

3. Bundle Analysis: Use webpack-bundle-analyzer to generate and compare dependency treemaps for pre- and post-refactor production builds.

4. API Contract Verification: For each removed dependency, verify its function was either (a) replaced with a native browser API, (b) reimplemented as a focused internal utility, or (c) deemed unnecessary.

Visualizations

Browser Refactoring and Optimization Workflow

Optimized Client-Side Caching Data Flow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Software & Data Components for Epigenomic Browser Research

| Item | Function in Research | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Refactored WashU Browser Core | Lightweight, maintainable visualization engine for local or private dataset exploration. | Customizable npm package post-refactor. |

| HiTile & BigWig Data Server | Serves optimized, chunked epigenomic quantitative data (e.g., ChIP-seq, methylation). | hitile-js server; enables rapid range queries. |

| IndexedDB / Chromium Cache API | Client-side persistence layer for caching pre-fetched data chunks, reducing server load. | Native browser API; post-refactor cache system. |

| Session JSON Schema | Standardized format to save/load the complete state of the browser (tracks, viewport, settings). | Critical for reproducible research; simplified in refactor. |

| Data Validation Scripts | Ensure custom dataset files conform to required formats before integration, preventing errors. | e.g., validateBigWig.js. |

| Performance Profiling Tools | Browser DevTools (Memory, Performance tabs) and webpack-bundle-analyzer. |

Used to audit and verify optimization gains. |

| Modular Analysis Plugins | Post-refactor, optional packages for peak calling, correlation, statistical overlays. | Can be developed and integrated independently. |

Diagnosing Slowdowns: A Troubleshooting Guide for Cache Performance Issues

Technical Support & Troubleshooting

This support center provides guidance for researchers optimizing caching mechanisms for large epigenomic datasets. The following FAQs address common experimental issues.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My cache hit rate is consistently below 50%. What are the primary factors I should investigate?

A: A low cache hit rate often indicates an inefficient caching strategy. First, examine your cache eviction policy (e.g., LRU, LFU). For epigenomic data access patterns, which can be sequential across genomic regions, LRU may be suboptimal. Second, review your cache key design. Ensure it aligns with common query patterns (e.g., [assembly_version:chromosome:start:end:data_type]). Third, verify your cache size; it may be too small for the working set of your analysis. Implement monitoring to profile data access frequency and adjust accordingly.

Q2: Retrieval latency has high percentile variance (P99 spikes). How can I diagnose this? A: High tail latency often stems from cache contention or memory pressure. 1) Check for memory overhead causing garbage collection stalls in managed languages (Java/Python). Instrument your application to log GC events and correlate with latency spikes. 2) Check for "cache stampedes" where many concurrent requests miss for the same key, all computing the value simultaneously. Implement a "compute-once" locking mechanism or use a probabilistic early expiration (e.g., "refresh-ahead") strategy. 3) Profile your data loading function; the P99 spike may reflect the cost of loading a particularly large or complex epigenomic region (e.g., a chromosome with dense methylation data).

Q3: Memory overhead is exceeding my allocated capacity. What are the most effective mitigation strategies? A: Excessive memory overhead can cripple system stability. Consider these steps:

- Data Serialization: Switch from language-native serialization (e.g., Java serialization, Python pickle) to efficient binary formats like Protocol Buffers or Apache Avro, which have smaller footprints.

- Compression: Apply fast, in-memory compression algorithms (e.g., LZ4, Snappy) to cached values, especially for large matrix data (e.g., chromatin accessibility scores). Weigh the CPU cost against memory savings.

- Dimensionality Reduction: For intermediate results, consider storing only essential data. For example, cache summarized quantifications (e.g., mean signal per region) instead of full raw signal vectors where scientifically permissible.

- Tune Object Metadata: In-memory caches (like Memcached or Redis) have per-key overhead. Batch smaller items or increase the minimum slab size to reduce waste.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Graduated Performance Degradation Over Time Symptoms: Cache hit rate and retrieval latency slowly worsen over days of running an epigenomic pipeline. Diagnostic Steps:

- Profile Access Patterns: Log a sample of cache keys and requests. Analyze for a shift in the workload (e.g., from random access to long sequential scans).

- Monitor Eviction Rate: A steadily increasing eviction rate indicates your cache size is insufficient for the growing dataset or that your cache is not effectively retaining hot items.

- Check for Memory Fragmentation: Use tools like

jemallocstats orRedis INFOto assess memory fragmentation ratio. A high ratio (>1.5) can increase overhead and latency. Resolution: Implement a dual caching strategy: a small, fast LRU cache for recent "hot" data and a larger, disk-backed cache (e.g., RocksDB) for less frequently accessed historical datasets. Schedule regular cache warm-up routines based on predicted analysis jobs.

Issue: Inconsistent Results After Cache Update Symptoms: Computational pipeline results change after a cache cluster restart or update, despite identical input data. Diagnostic Steps:

- Validate Cache Invalidation: Ensure all pipelines that write source data trigger explicit invalidation of dependent cached results. In epigenomics, this could be a new version of a genome annotation file.

- Check Serialization Versioning: Different versions of serialized objects (e.g., after a software update) can cause deserialization errors or silent data corruption. Verify consistent library versions across all nodes.

- Audit Cache Key Collisions: Two different logical items (e.g., data for chr1:1000-2000 and chr11:000-2000) may generate identical keys due to a hashing bug.

Resolution: Implement a versioned cache key schema (e.g.,

v2:[experiment_id]:[key_hash]). Use a distributed locking service (like ZooKeeper or etcd) to manage coordinated cache invalidation events across the research cluster.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Table 1: Typical Target Ranges for Caching Metrics in Epigenomic Data Analysis (Synthesized from Recent Benchmarks)

| Metric | Optimal Range | Alert Threshold | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cache Hit Rate | 85% - 99% | < 70% | (Total Hits / (Total Hits + Total Misses)) * 100 |

| Retrieval Latency (P50) | 1 - 10 ms | > 50 ms | Measured at client; time from request to response receipt. |

| Retrieval Latency (P99) | < 100 ms | > 500 ms | Measured at client; 99th percentile value. |

| Memory Overhead | < 30% of cache size | > 50% of cache size | ((Memory Used - Raw Data Size) / Raw Data Size) * 100 |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Measuring Cache Performance for Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) Preprocessing

Objective: To evaluate the impact of different cache policies (FIFO, LRU, LFU) on the performance of a pipeline that fetches chromatin state annotations for millions of genetic variants.

Materials:

- Input Data: VCF file from a GWAS, ENCODE chromatin state segmentation files (bigWig format).

- Software: Custom Python pipeline,

redis-pyclient, Redis 7+ server, monitoring script (redis-cli --stat). - Hardware: Compute node with 64GB RAM, 16-core CPU.

Methodology:

- Baseline: Run the pipeline with caching disabled. Log total runtime (

T_none). - Cache Configuration: Configure a Redis cache with a 16GB maximum memory limit. Prepare three identical instances.

- Policy Testing: For each cache eviction policy (volatile-lru, volatile-lfu, allkeys-lru):

a. Pre-load the cache with chromatin state data for chromosomes 1-5.

b. Execute the GWAS preprocessing pipeline, which requests annotations for variants in a shuffled order.

c. Use

redis-cli INFO statsto recordkeyspace_hits,keyspace_misses, andused_memory. d. Record total pipeline runtime (T_policy). - Data Collection: Calculate Cache Hit Rate, Average Retrieval Latency (from client-side instrumentation), and Memory Overhead for each run.

- Analysis: Compute speedup:

(T_none - T_policy) / T_none. Correlate speedup with cache hit rate and latency metrics.

Visualizations

Cache Decision Workflow for Epigenomic Data Query

Logical Relationships Between Key Caching Metrics and Factors

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Software & Libraries for Caching Experiments in Epigenomics

| Item Name | Category | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Redis / Memcached | In-Memory Data Store | Serves as the primary caching layer for low-latency storage of precomputed results, annotations, and intermediate data matrices. |

| Apache Arrow | In-Memory Format | Provides a language-agnostic, columnar memory format that enables zero-copy data sharing between processes (e.g., Python and R), reducing serialization overhead. |

| RocksDB | Embedded Storage Engine | Acts as a disk-backed cache or for storing very large, less-frequently accessed datasets with efficient compression. |

| Prometheus & Grafana | Monitoring Stack | Collects and visualizes metrics (hit rate, latency, memory usage) in real-time for performance benchmarking and alerting. |

| UCSC bigWig/bigBed Tools | Genomic Data Access | Utilities (bigWigToWig, bigBedSummary) used in the "compute" step to fetch raw data from genomic binary indexes on cache misses. |

Python pickle / joblib |

Serialization (Baseline) | Commonly used but inefficient serialization protocols; serve as a baseline for comparing performance against advanced formats. |

| Protocol Buffers (protobuf) | Efficient Serialization | Used to define and serialize structured epigenomic data (e.g., a set of peaks with scores) with minimal overhead and fast encoding/decoding. |

| LZ4 Compression Library | Compression | A fast compression algorithm applied to cached values to reduce memory footprint at a minor CPU cost. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: During our experiment simulating cache policies, the hit rate for popular epigenomic feature files (e.g., .bigWig) is significantly lower than predicted by the model. What could be causing this discrepancy?

A1: This is a common issue when the assumed data popularity distribution doesn't match real-world access patterns. Follow this protocol to diagnose:

- Instrumentation: Modify your caching simulator or middleware to log every data access (client ID, file ID, timestamp, file size) over a 48-hour period.

- Analysis: Process the log to calculate the actual popularity distribution (frequency of access per file). Plot it against the assumed Zipf or Pareto distribution used in your model.

- Validation: Re-run your cache placement algorithm (e.g., LRU-k, LFU-DA) using the empirically derived popularity values. Compare the hit rate to your initial experimental result.

Q2: We implemented a Time-To-Live (TTL) based validity strategy for cached datasets, but we are seeing high rates of stale data being served after genome assembly updates. How should we adjust our strategy?

A2: TTL alone is insufficient for rapidly changing reference data. Implement a hybrid validity protocol:

- Tag-Based Invalidation: Each dataset in the cache must be tagged with a unique version hash (e.g.,

GRCh38.p14_<dataset_id>_<checksum>). - Callback Mechanism: Set up a subscription for your cache nodes to a central metadata update service (e.g., using pub/sub). Upon a new data release, the service broadcasts invalidation messages for specific version tags.

- Graceful Staleness: For non-critical metadata, configure a layered TTL: a short TTL (e.g., 1 hour) for strong consistency checks against the origin, and a longer one (e.g., 24 hours) for serving data if the origin is unreachable, with clear logging of the staleness.

Q3: When deploying a multi-tier cache (in-memory + SSD) for large BAM/CRAM files, how do we optimally split content between tiers based on the popularity-validity framework?

A3: Use a dynamic promotion/demotion protocol. This experiment requires monitoring two metrics:

- Popularity Score (P): Access frequency over a sliding 24-hour window.

- Validity Score (V):

(TTL_remaining / Total_TTL). A score near 0 indicates impending expiry.

| Metric Score Range | Tier Placement Action | Rationale |

|---|---|---|