Decoding X-Chromosome Inactivation: Epigenetic Mechanisms, Methodologies, and Clinical Implications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the epigenetic regulation of X-chromosome inactivation (XCI), a fundamental process in mammalian dosage compensation.

Decoding X-Chromosome Inactivation: Epigenetic Mechanisms, Methodologies, and Clinical Implications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the epigenetic regulation of X-chromosome inactivation (XCI), a fundamental process in mammalian dosage compensation. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational biology driven by the non-coding RNA XIST and its associated chromatin modifiers. The scope extends to established and emerging methodologies for profiling XCI status, addresses key experimental challenges in the field, and offers comparative insights into model systems and validation techniques. By synthesizing current knowledge and technological advances, this review aims to bridge fundamental research with therapeutic applications, particularly in the realm of X-linked diseases.

Core Mechanisms: From XIST to Heterochromatin

The Central Role of the X-Inactivation Center (Xic) and XIST Non-Coding RNA

X-chromosome inactivation (XCI) is the fundamental epigenetic process in female placental mammals that ensures dosage compensation for X-linked genes between sexes (XX females and XY males) by transcriptionally silencing one of the two X chromosomes in somatic cells [1] [2]. This process is orchestrated by a master regulatory locus on the X chromosome known as the X-inactivation center (Xic) [3] [4]. The concept of the Xic dates back to the 1960s, but its molecular characterization remained elusive for nearly three decades until the discovery of the X-inactive specific transcript (XIST/Xist) gene [3]. The Xic is defined genetically as the cis-acting locus required for an X chromosome to undergo inactivation early in female embryogenesis [3]. Transgenic experiments have demonstrated that DNA from the Xic, including Xist and its regulatory sequences, can largely recapitulate X inactivation [3].

In both humans and mice, the XIC/Xic maps to a complex genomic region encompassing more than 1 Mb on the X chromosome and contains several genes involved in the XCI process [1]. The Xic coordinates multiple steps of XCI: counting (assessing the number of X chromosomes), choice (designating which X chromosome will become inactive), initiation (triggering silencing), and maintenance (stably preserving the inactive state through cell divisions) [3]. The Xic ensures that in diploid cells with more than two X chromosomes, all but one X chromosome are inactivated [2].

Molecular Components of the X-Inactivation Center

The X-inactivation center contains several critical genes and regulatory elements that work in concert to control the XCI process. These components form a complex regulatory network that determines the fate of each X chromosome in female cells.

Table 1: Key Molecular Components of the X-Inactivation Center

| Component | Type | Function in XCI | Conservation |

|---|---|---|---|

| XIST/Xist | Long non-coding RNA | Master regulator; coats the future inactive X chromosome and initiates silencing | Conserved in humans and mice |

| Tsix | Antisense non-coding RNA | Negative regulator of Xist; influences choice of inactive X | Conserved in humans and mice |

| Xite | Non-coding RNA | Positive regulator of Tsix expression | Identified in mice |

| Jpx | Non-coding RNA | Activates Xist transcription in a dose-dependent manner | Conserved in humans and mice |

| Ftx | Non-coding RNA | Promotes Xist transcription through locus proximity | Conserved in humans and mice |

| Xce (X-controlling element) | Genetic locus | Influences choice step through allele strength variants | Primarily characterized in mice |

XIST/Xist: The Master Regulator

XIST (X-inactive specific transcript) is the fundamental orchestrator of X-chromosome inactivation and remains the most critical component of the Xic [4]. XIST is a large (17 kb in humans, 15 kb in mice) long non-coding RNA that is exclusively expressed from the future inactive X chromosome (Xi) and remains tightly associated with it in the form of a nuclear RNA cloud [3] [1]. Gene knockout studies in female embryonic stem cells and mice have demonstrated that X chromosomes bearing a deletion of the Xist gene are unable to undergo inactivation, confirming its essential role in the silencing process [1] [4].

The developmental regulation of Xist expression is complex. In pre-implantation mouse embryos, Xist is expressed from the paternal X chromosome, reflecting imprinted XCI in extraembryonic tissues [4]. This imprinted inactivation is subsequently reversed in the inner cell mass (which gives rise to the embryo proper), after which random XCI is initiated around the time of gastrulation [1]. In female embryonic stem cells, which serve as a primary model for studying XCI, both X chromosomes are active in the undifferentiated state, but random XCI is triggered upon differentiation, recapitulating the embryonic process [1] [4].

Tsix: The Antisense Regulator

Tsix is a major negative regulator of Xist that is transcribed in the antisense direction relative to Xist and fully overlaps with the Xist locus [3] [1]. Tsix produces a 40 kb transcript that remains localized to the Xic and functions as the critical regulatory "switch" that determines whether Xist is activated or repressed [3]. Prior to XCI, Tsix is expressed from both X chromosomes at levels 10-100 times higher than Xist [1]. During the initiation of XCI, Tsix is turned off on the future inactive X (leading to Xist upregulation) but persists longer on the future active X (where it keeps Xist silenced) [3].

Targeted mutation studies have confirmed Tsix's essential role in Xist regulation. Deletion of a 2-kb region at the 5' end of Tsix or sequences near its CpG island results in constitutive Xist expression and non-random inactivation of the mutated X chromosome [3]. Conversely, persistent high-level expression of Tsix from a constitutive knock-in allele is sufficient to block Xist accumulation and prevent X inactivation [3]. The mechanisms of Tsix-mediated Xist repression may involve transcriptional interference, RNA-mediated silencing, or regulation of the methylation status of the Xist promoter [1].

Additional Regulatory Components

The Xite (X-chromosome intergenic transcript element) locus is located approximately 10 kb upstream of Tsix and functions as a positive regulator of Tsix expression [1]. Deletion of Xite reduces antisense transcription through the Xist locus, leading to impaired Tsix function [1].

The Xce (X-controlling element) locus was defined genetically decades before the molecular components were identified and maps at least 40 kb away from the Xist 3' end or Tsix promoter [3]. Different Xce alleles vary in their "strength," influencing the choice step of XCI such that a chromosome carrying a strong Xce allele has a greater probability of remaining active [3] [4]. While the molecular nature of Xce remains incompletely characterized, targeted deletion studies have implicated sequences in this region in counting and choice independent of Tsix transcription [3].

Additional non-coding RNAs such as Jpx and Ftx also contribute to Xist regulation. Jpx activates Xist transcription in a dose-dependent manner by evicting the insulator protein CTCF, which normally represses Xist expression [5]. Ftx promotes Xist transcription through spatial proximity of their gene loci, independent of its RNA products [5].

Mechanisms of XIST-Mediated Chromosome Silencing

XIST RNA orchestrates X-chromosome silencing through a sophisticated multi-step process that involves chromosome coating, recruitment of repressive complexes, and establishment of stable heterochromatin.

XIST RNA Structure and Functional Domains

The XIST RNA contains multiple conserved repetitive motifs that serve as modular platforms for recruiting specific protein complexes essential for silencing [5] [6]. These repeats, designated A through F, function as distinct functional domains that coordinate different aspects of the silencing process [6].

Table 2: XIST RNA Functional Domains and Their Roles in Silencing

| Repeat Domain | Key Binding Proteins | Function in XCI | Molecular Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| A-Repeat | SPEN/SHARP, RBM15/RBM15B | Initiates gene silencing | Recruits HDAC3 via SPEN; recruits m6A machinery via RBM15 |

| B/C-Repeat | HNRNPK | Stabilizes silent state | Recruits PRC1 complex leading to H2AK119ub |

| E-Repeat | PTBP1, MATR3, TDP-43, CELF1 | Forms silencing condensates | Mediates liquid-liquid phase separation for XIST compartmentalization |

| C-Repeat | YY1 | Tethers XIST to nucleation center | Anchors XIST to inactive X nucleation center |

Chromosome Coating and Condensate Formation

Upon activation, XIST RNA is transcribed from the future inactive X chromosome and immediately begins to "coat" the chromosome in cis [5]. Recent evidence indicates that XIST forms approximately 50 locally confined loci in open chromatin regions on the Xi, with each locus containing 2 XIST RNA molecules that nucleate supramolecular complexes (SMACs) [5]. These complexes gradually expand across the Xi, creating gradients of silencing proteins over broad genomic regions [5].

A groundbreaking discovery in the field is that XIST-mediated silencing involves liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS), a biophysical process that drives the formation of membraneless condensates [6]. The E-repeat of XIST RNA plays a critical role in this process by recruiting RNA-binding proteins such as PTBP1, MATR3, TDP-43, and CELF1, which form condensates through self-aggregation and protein interactions [5] [6]. These condensates, seeded by the XIST RNA's E-repeat, are crucial for gene silencing during both XIST-dependent and independent phases of XCI [5].

Recruitment of Repressive Complexes and Chromatin Modifications

XIST RNA achieves transcriptional silencing through the coordinated recruitment of multiple repressive complexes that catalyze distinct chromatin modifications:

Histone Deacetylation: The A-repeat of XIST binds to the corepressor SPEN (SHARP), which interacts with the SMRT co-repressor and activates pre-loaded histone deacetylase HDAC3 on the Xi, resulting in the removal of active chromatin marks such as H3K27ac [5] [7] [6].

Polycomb Recruitment: The B-repeat of XIST RNA recruits Polycomb repressive complexes PRC1 and PRC2 through direct binding with HNRNPK, establishing the repressive chromatin marks H2AK119ub and H3K27me3 on the Xi [5] [6]. PRC2-mediated H3K27me3 deposition is facilitated by prior PRC1-catalyzed H2AK119ub [6].

RNA m6A Modification: XIST recruits the m6A methylation machinery through interactions between its A-repeat and RBM15/RBM15B proteins, which further recruit the METTL3/14 methyltransferase complex to modify specific sites on XIST RNA [5]. In humans, this m6A modification is recognized by the reader protein YTHDC1, which promotes gene silencing through mechanisms that remain under investigation [5].

Nuclear Compartmentalization: XIST interacts with the Lamin B receptor (LBR) through its A-repeat, facilitating the recruitment of the Xi to the nuclear lamina and enabling XIST to spread across the chromosome [5]. This spatial repositioning to the nuclear periphery contributes to the stable silencing of the X chromosome.

Experimental Approaches and Research Toolkit

The molecular dissection of Xic and XIST function has relied on sophisticated genetic, cellular, and biochemical approaches. Here we detail key experimental methodologies that have advanced our understanding of XCI.

Genetic Manipulation Studies

Targeted Mutagenesis in Embryonic Stem Cells: Female mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells represent the predominant model system for studying XCI, as they retain two active X chromosomes in the undifferentiated state and undergo random XCI upon differentiation [1] [4]. Gene targeting approaches have been instrumental in establishing the functions of Xic components:

Xist Deletion: Knockout of Xist in female ES cells demonstrates that chromosomes lacking Xist cannot undergo inactivation [1] [4]. In somatic cells, deletion of Xist does not lead to reactivation of the inactive X, indicating its requirement for initiation but not necessarily maintenance of XCI [4].

Tsix Mutagenesis: Deletion of specific regions within Tsix, particularly a 2-kb segment at the 5' end or sequences near the CpG island, results in constitutive Xist expression and non-random inactivation of the mutated X chromosome [3]. Truncation of Tsix to 93% of its normal length fails to induce Xist silencing, indicating that antisense transcription through the Xist promoter is crucial for establishment of repressive chromatin marks [1].

Constitutive Expression Systems: Introduction of a constitutive active promoter (e.g., human EF1α) to drive persistent Tsix expression demonstrates that sustained Tsix transcription is sufficient to block Xist accumulation and prevent X inactivation, confirming Tsix's role as a critical switch in the choice process [3].

Proteomic and Genomic Approaches

Comprehensive Identification of RNA-Binding Proteins by Mass Spectrometry (ChIRP-MS): This method involves crosslinking lncRNAs and proteins in vivo, followed by stringent, antisense-mediated purification of directly interacting proteins [5] [7]. Stable isotope labeling by amino acids in culture (SILAC) enables quantitative comparison of purified proteins by mass spectrometry between experimental and control RNA purifications [7]. Application of ChIRP-MS to XIST has identified a highly specific set of direct interactors, including SAFA/HNRNPU, SHARP/SPEN, and LBR, which were subsequently validated as essential for XIST-mediated silencing [7].

RNA Antisense Purification (RAP-MS): Similar to ChIRP-MS, RAP-MS combines in vivo crosslinking with antisense-mediated purification of XIST ribonucleoprotein complexes, followed by quantitative mass spectrometry [7]. This approach has been particularly valuable for mapping transient interactions and identifying proteins that mediate phase separation of XIST condensates [6].

CRISPR/Cas9 Screening: Genome-wide loss-of-function CRISPR/Cas9 screens in female fibroblast cell lines have identified novel regulators of XCI, including unexpected roles for microRNAs [8]. These screens utilize cell lines with selectable markers (e.g., Hprt) on the Xi, enabling identification of genes whose disruption leads to reactivation of the silent X chromosome [8].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for XIC/XIST Studies

| Reagent/Cell Line | Application | Key Features | Experimental Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female mouse ES cells | XCI differentiation model | Two active X chromosomes in undifferentiated state; undergo random XCI upon differentiation | Study of XCI initiation in vitro |

| TSA-8 (Xist-inducible) | Controlled Xist expression | Male mouse ES cells with Xist transgene under inducible promoter | Study of Xist function without developmental complexity |

| BMSL213 cell line | CRISPR screening | Female mouse fibroblasts with Hprt only on Xi | Identification of XCI regulators through HAT selection |

| Xist A-repeat deletion mutants | Functional domain mapping | Deletion of 0.9 kb at 5' end abolishes silencing capacity | Determination of A-repeat essential role in silencing initiation |

| Anti-XIST FISH probes | Spatial localization | Fluorescently labeled probes for XIST RNA detection | Visualization of XIST coating by RNA FISH |

| XIST-repeat specific antibodies | Protein interaction studies | Antibodies against specific XIST repeat regions | Mapping protein interactions with modular XIST domains |

| Poziotinib | Poziotinib, CAS:1092364-38-9, MF:C23H21Cl2FN4O3, MW:491.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Tiagabine | Tiagabine, CAS:115103-54-3, MF:C20H25NO2S2, MW:375.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

The understanding of Xic and XIST biology has profound implications for therapeutic interventions, particularly for X-linked disorders where reactivation of the silent wild-type allele could ameliorate disease symptoms.

X-Chromosome Reactivation Strategies

Pharmacological Approaches: Small molecule inhibitors targeting key components of the XCI machinery represent a promising therapeutic strategy. For example, inhibition of XIST-interacting proteins such as SHARP/SPEN or HDAC3 might facilitate partial reactivation of the Xi [7] [6]. Similarly, modulation of the microRNAs that regulate XIST function, such as miR106a, has shown promise in preclinical models [8].

Genetic and Epigenetic Editing: CRISPR-based technologies enable targeted reactivation of specific genes on the Xi without global derepression [6]. Approaches include CRISPRa (activation) systems that recruit transcriptional activators to specific X-linked genes, or epigenetic editors that remove repressive marks from target loci [8] [6].

Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation Modulation: Emerging understanding of XIST condensate formation through LLPS provides novel therapeutic opportunities [6]. Small molecules that modulate the biophysical properties of these condensates could potentially disrupt the maintenance of XCI in a controlled manner, allowing for selective reactivation of therapeutic targets [6].

Disease Applications

Rett Syndrome: Rett syndrome is an X-linked neurodevelopmental disorder caused by mutations in the MECP2 gene, primarily affecting females [8]. Reactivation of the silent wild-type MECP2 allele on the Xi represents a promising therapeutic approach. Recent studies demonstrate that inhibition of miR106a, which regulates XIST function, significantly improves multiple disease facets in Rett syndrome mouse models, including increased lifespan, enhanced locomotor activity, and diminished breathing abnormalities [8].

X-Linked Autoimmune Disorders: Many autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and systemic sclerosis (SSc), show strong female bias [9]. This predisposition is linked to XCI escape of immune-related genes such as TLR7 and TLR8, which are located on the X chromosome [9]. In patients with SSc, subsets of plasmacytoid dendritic cells show dysregulated expression of TLR7 and TLR8 due to escape from XCI, contributing to chronic inflammation and fibrosis [9]. Therapeutic strategies that normalize the expression of these escaped genes could potentially ameliorate autoimmune pathology.

XCI Erosion in Stem Cell Therapies: Female human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) frequently undergo XCI erosion, characterized by XIST RNA loss and partial reactivation of the Xi [10]. This phenomenon poses challenges for stem cell applications but also offers insights into reactivation strategies. Understanding the mechanisms that maintain XCI stability versus those that permit erosion may identify new targets for therapeutic Xi reactivation [10].

The continued dissection of Xic and XIST mechanisms will undoubtedly yield additional therapeutic insights and opportunities. As our understanding of the epigenetic regulation of XCI deepens, particularly regarding the biophysical properties of XIST condensates and the nuances of maintenance versus reversibility, new avenues for manipulating this process for therapeutic benefit will continue to emerge.

X-chromosome inactivation (XCI) stands as a foundational model for understanding chromosome-wide epigenetic silencing in mammals. This dosage compensation mechanism, which transcriptionally silences one of the two X chromosomes in female cells, ensures balanced X-linked gene expression between XY males and XX females [11]. The process represents one of biology's most striking examples of large-scale epigenetic reprogramming, involving coordinated changes in non-coding RNA expression, histone modifications, DNA methylation, and three-dimensional chromosome architecture [12] [13]. The initiation and establishment phases of XCI encompass a precisely orchestrated sequence of molecular events, beginning with the counting of X-chromosomes and choice of which X to inactivate, progressing through chromosome-wide silencing, and culminating in the stable maintenance of the heterochromatic state throughout subsequent cell divisions [11]. Recent technical advances have revealed that XCI establishment involves dramatic reorganization of the X chromosome's architecture through stepwise folding mechanisms that balance essential gene activation with global silencing [13]. This whitepaper examines the multistep process of chromosome-wide silencing through the lens of XCI, providing researchers with a comprehensive technical guide to the molecular mechanisms, experimental methodologies, and emerging insights in this rapidly evolving field.

Molecular Mechanisms of XCI Initiation

The Central Role of Xist RNA

The initiation of XCI is fundamentally dependent on the long non-coding RNA Xist (X-inactive specific transcript), which is transcribed from the X-inactivation center (Xic) on the chromosome destined for silencing [12] [11]. Following its transcription, Xist RNA undergoes cis-localized coating along the future inactive X chromosome (Xi), forming a nuclear territory that can be visualized by RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) [14]. This coating action initiates a cascade of chromosomal changes, beginning with the rapid depletion of RNA polymerase II and transcription factors from the Xist-coated chromatin domain [11]. The molecular architecture of Xist contains functionally distinct regions, with the highly conserved A-repeat region on exon 1 being particularly critical for Xist's gene-silencing function, while other regions facilitate chromosomal coating and protein recruitment [12].

Genetic dissection experiments have demonstrated that Xist is not only necessary for initiation but also plays unexpected roles in maintenance phases, as deletion of Xist in adult mice leads to cancer with high penetrance, suggesting its essential role in preserving Xi stability [11]. Interestingly, in human T-cell development, XCI remains remarkably stable throughout differentiation and appears independent of continuous XIST expression, indicating potential lineage-specific variations in maintenance mechanisms [15].

Chromatin Modifications and Silencing Mechanisms

Following Xist coating, the targeted X chromosome undergoes profound chromatin remodeling through the sequential recruitment of repressive complexes. Early events include histone deacetylation and H2AK119 ubiquitination, followed by the accumulation of Polycomb-mediated H3K27me3 marks, which characterize the facultative heterochromatin of the Xi [12] [13]. The kinetics of gene silencing during this process varies significantly across the X chromosome, with distinct groups of genes being silenced at early, mid, or late stages of XCI [12]. This progression does not follow a simple linear gradient from the Xic but rather reflects the three-dimensional organization of the X chromosome, where spatial proximity to the Xic correlates with earlier silencing timing [12].

Recent research utilizing low-input Hi-C methods has revealed that TAD attenuation on the Xi occurs during imprinted XCI in early mouse embryos, with early-silenced genes showing TAD weakening as early as the eight-cell stage [13]. The relationship between architectural changes and silencing appears interdependent, as disruption of structural proteins like cohesin impairs proper XCI establishment and leads to ectopic activation of regulatory elements and genes near Xist [13].

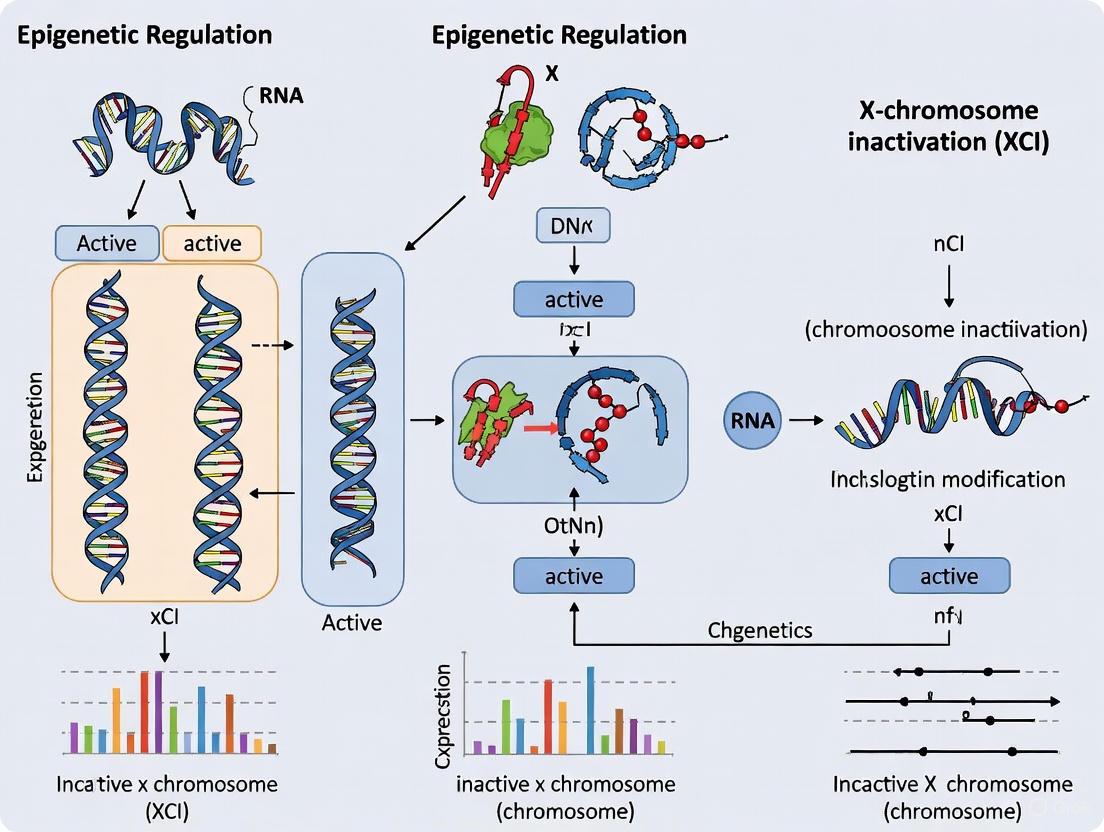

Figure 1: Molecular Cascade of X-Chromosome Inactivation Initiation. This pathway illustrates the sequential epigenetic events following XIST RNA coating, from initial transcription factor exclusion to stable heterochromatin formation.

Chromatin Architecture Reorganization During XCI Establishment

Stepwise Chromosome Folding Dynamics

The establishment of XCI involves dramatic three-dimensional restructuring of the X chromosome, progressing through distinct architectural stages. Recent in vivo studies using low-input Hi-C methods have revealed that the inactive X chromosome undergoes stepwise folding during early development, beginning with the formation of unique megadomain structures separated at the Xist locus (X-megadomains) before transitioning to the canonical Dxz4-delineated bipartite organization (D-megadomains) observed in later developmental stages [13]. This structural progression occurs alongside transcriptional silencing, with gene repression actually preceding the formation of mature megadomains, suggesting that architectural reorganization consolidates rather than initiates the silenced state [13].

The X chromosome exhibits dynamic compartmentalization during XCI establishment, with compartment strength initially increasing on the future Xi during early embryonic stages before diminishing as silencing is locked in. In blastocyst-stage embryos, the Xi displays broader compartments resembling the S1/S2 compartments previously observed in differentiating embryonic stem cells, which eventually merge into a compartment-less architecture through the action of structural proteins like SMCHD1 [13]. This transition represents a fundamental reorganization of the chromosome's spatial arrangement, from defined active and inactive compartments toward a more homogeneous spatial configuration characteristic of facultative heterochromatin.

Escape from XCI and Boundary Elements

A remarkable aspect of XCI is that approximately 15-23% of X-linked genes in humans escape complete silencing and remain expressed from the otherwise inactive X chromosome [15] [11]. These "escapee" genes are not randomly distributed but tend to cluster, particularly on the short arm of the X chromosome, and their expression underpins the molecular basis for sex differences in immune function and other physiological processes [15] [11]. The mechanisms protecting these genes from silencing remain an active area of investigation, with evidence suggesting that specific insulator elements and transcription factors may create boundaries that limit the spread of Xist-mediated repression.

Research using RNA-antisense purification (RAP) and CHART-seq mapping has revealed that constitutive escapees like Jarid1c are surrounded by Xist-binding sites that show abrupt depletion at these loci, suggesting the presence of sequence features or chromatin contexts that resist Xist propagation [12]. The DNA-binding protein CTCF has been implicated in this boundary function, with evidence showing it associates with the transcription start sites of escaping genes on the X chromosome, though it appears insufficient alone to confer escape capacity [12]. Understanding the precise mechanisms governing escape from XCI has important clinical implications, as dosage imbalances of these genes contribute to the pathologies associated with sex chromosome aneuploidies like Turner, Klinefelter, and XXX syndromes [11].

Table 1: Dynamic Changes in X Chromosome Architecture During Inactivation Establishment

| Developmental Stage | Architectural Features | Compartment Status | TAD Organization | Silencing Progression |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-XCI (Early Embryo) | Standard autosome-like organization | Strong A/B compartments | Preserved TADs | Biallelic expression |

| Early Establishment | Xist-separated X-megadomains | Strengthened, broader compartments | Early-silenced genes show TAD attenuation | Progressive silencing initiation |

| Intermediate Stage | S1/S2 compartment formation | Compartment strengthening | Significant TAD diminution | Mid-stage silencing |

| Late Establishment | Dxz4-delineated D-megadomains | Diminished compartments | Highly attenuated TADs | Near-complete silencing with defined escapees |

| Maintenance Phase | Stable bipartite structure | Compartment-less architecture | Absent TADs | Stable heterochromatin with constitutive escapees |

Experimental Models and Methodologies for Studying XCI

Key Model Systems

The study of XCI establishment relies on several experimental model systems, each offering unique advantages for dissecting different aspects of the process. Mouse models have been particularly instrumental due to the ability to manipulate early development and the existence of well-characterized imprinted XCI in extraembryonic tissues [11] [13]. Mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) provide a powerful in vitro system for studying random XCI during differentiation, allowing genetic and chemical perturbations that would be challenging in whole organisms [12] [13]. Recent research has also incorporated human cellular systems, including T-cell development trajectories from pediatric thymi and human pluripotent stem cells, revealing both conserved and species-specific features of XCI [15].

Studies of sex chromosome aneuploidies have provided natural models for understanding XCI regulation, with samples from Turner syndrome (45,X), Klinefelter syndrome (47,XXY), and completely skewed XCI females offering insights into how the XCI machinery adapts to abnormal X-chromosome numbers [15]. These patient-derived samples have been particularly valuable for establishing correlations between escape gene dosage and phenotypic severity across different conditions [11].

Advanced Genomic and Imaging Techniques

Modern understanding of XCI establishment has been propelled by sophisticated genomic technologies that enable allele-specific resolution of chromatin states. Low-input in situ Hi-C (sisHi-C) methods have allowed mapping of 3D chromosome architecture during early embryonic stages, revealing the stepwise folding of the Xi [13]. Single-cell RNA sequencing has provided unprecedented views of silencing kinetics during pre-implantation development, demonstrating the relationship between spatial proximity to the Xic and silencing timing [12]. Meanwhile, RNA-antisense purification (RAP) and CHART-seq approaches have mapped Xist RNA-chromatin contacts at high resolution, establishing that Xist initially binds regions with high 3D proximity to the Xic [12].

For protein localization studies, CUT&RUN and related methods have enabled mapping of transcription factor and architectural protein binding with minimal cell input, crucial for early embryo work [13]. Traditional approaches like RNA-DNA FISH remain essential for validating spatial organization and visualizing Xist RNA clouds and Barr body formation, providing critical spatial context to complement sequencing-based methods [14].

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Analyzing XCI Establishment. This diagram outlines the integrated multi-omics approach for studying the spatiotemporal dynamics of chromosome-wide silencing, from sample preparation through computational modeling.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Experimental Tools for XCI Studies

| Reagent/Technology | Specific Application | Key Function | Example Utility in XCI Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Xist-inducible mESC Systems | Controlled initiation of XCI | Doxycycline-regulated Xist expression enables synchronized silencing studies | Dissecting temporal hierarchy of chromatin changes during XCI establishment [12] |

| Low-input in situ Hi-C (sisHi-C) | 3D chromatin architecture mapping | Allele-specific chromosome conformation capture with minimal cell input | Revealing stepwise X chromosome folding in early embryos [13] |

| Allele-specific RNA-seq | Transcriptional profiling | Distinguishes parental allele expression using SNP polymorphisms | Quantifying XCI kinetics and escape gene expression in hybrid systems [15] [13] |

| RNA-DNA FISH | Spatial organization validation | Simultaneous detection of Xist RNA and chromosomal DNA | Visualizing Xist coating and Barr body formation [14] |

| CUT&RUN | Protein-DNA interaction mapping | High-resolution mapping of transcription factor binding with low background | Identifying CTCF and cohesin binding at escapee genes and architectural boundaries [13] |

| Single-cell RNA-seq | Silencing kinetics analysis | Transcriptome-wide gene expression at individual cell level | Resolving heterogeneity in XCI timing and escape patterns [12] |

| ATAC-seq | Chromatin accessibility profiling | Transposase-based mapping of open chromatin regions | Identifying regulatory elements active on Xi and escapee regions [12] |

| Olprinone hydrochloride | Olprinone hydrochloride, CAS:119615-63-3, MF:C14H11ClN4O, MW:286.71 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Cercosporamide | Cercosporamide, CAS:131436-22-1, MF:C16H13NO7, MW:331.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Implications for Disease and Development

The precise establishment of XCI has profound implications for human health and disease, with disruptions in this process contributing to various pathological conditions. The female bias in autoimmune diseases like systemic lupus erythematosus and multiple sclerosis has been linked to the biallelic expression of X-linked immune genes such as CD40LG, TLR7, and CXCR3 that escape XCI [15]. Recent research on human T-cell development has revealed that XCI remains remarkably stable throughout thymocyte development, with escape gene expression potentially contributing to sex-specific differences in immune responses to infection and vaccination [15].

In the context of sex chromosome aneuploidies, the efficiency and patterns of XCI establishment directly influence disease severity. In Klinefelter syndrome (47,XXY), the presence of an extra X chromosome leads to overexpression of escape genes, while in Turner syndrome (45,X), haploinsufficiency for these same genes contributes to the characteristic phenotype [11]. The clinical variability observed in these conditions may reflect differences in XCI establishment and maintenance, including the degree of silencing skewing and tissue-specific variations in escape gene expression [11].

Beyond genetic disorders, recent evidence has implicated XCI dysregulation in cancer development, with deletion of Xist in hematopoietic cells leading to aggressive hematologic cancers with high penetrance in mouse models [11]. Similarly, human pluripotent stem cells often exhibit instability in XCI patterns, posing challenges for their therapeutic application but providing valuable models for understanding the molecular requirements for maintaining the silenced state [11]. These clinical connections highlight the importance of understanding XCI establishment not only as a fundamental biological process but also as a determinant of disease pathogenesis.

Future Directions and Unanswered Questions

Despite significant advances, key aspects of XCI establishment remain incompletely understood. The counting and choice mechanisms that ensure precisely one active X chromosome per diploid genome represent a continuing area of investigation, with the nature of the blocking factor that prevents all but one X chromosome from remaining active still elusive [11]. Similarly, the molecular basis for the heterogeneity in silencing kinetics across the X chromosome, with some genes resisting inactivation for multiple cell divisions before eventually becoming silenced, requires further exploration [12].

Technological developments continue to drive the field forward, with emerging methods for multimodal single-cell analysis offering opportunities to correlate chromatin architecture, epigenetic modifications, and transcriptional output within individual cells during XCI establishment. The application of live-cell imaging approaches to visualize the dynamics of Xist RNA spreading and chromosomal reorganization in real time represents another promising direction that could transform our understanding of the temporal coordination of these events.

From a clinical perspective, a more comprehensive understanding of tissue-specific differences in XCI patterns and escape gene expression may reveal novel therapeutic opportunities for X-linked disorders and sex chromosome aneuploidies. Similarly, elucidating the mechanisms that protect escape genes from silencing could inform strategies for reactivating specifically targeted genes on the Xi, offering potential treatments for X-linked diseases through manipulation of epigenetic states rather than direct genetic correction. As these research directions converge, the study of XCI establishment will continue to provide fundamental insights into chromosome biology while opening new avenues for therapeutic intervention.

X-chromosome inactivation (XCI) stands as a paradigm of epigenetic regulation in female mammals, essential for achieving dosage compensation for X-linked genes between XY males and XX females [16]. This process results in the formation of the transcriptionally silent Barr body, a condensed nuclear structure, and its maintenance involves a sophisticated, multi-layered epigenetic machinery [6]. The initiation, establishment, and maintenance of XCI are orchestrated by the long noncoding RNA Xist (X-inactive specific transcript), which coats the future inactive X chromosome (Xi) in cis and recruits a multitude of repressive complexes [6]. Understanding the interplay between histone modifications, DNA methylation, and nuclear reorganization is not only fundamental to biology but also critical for developing novel therapeutic strategies for X-linked disorders [6] [8]. This review dissects these core epigenetic layers, providing a technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals.

The Xist RNA: The Master Orchestrator of XCI

The Xist lncRNA is the central regulator of XCI, a ~17 kb transcript that is expressed from and coats the X chromosome destined for inactivation [6]. Its function is mediated through distinct repetitive regions (Repeats A through F), each recruiting specific protein complexes to enact silencing [6].

- Repeat A (RepA): Located at the 5' end, this region is critical for initiating gene silencing. It recruits the transcriptional repressor SPEN (SHARP), which in turn brings histone deacetylase complexes (e.g., NCOR/SMRT, HDAC3) to chromatin, reducing accessibility for RNA polymerase II [6]. RepA also recruits RBM15, which directs the m6A RNA methylation machinery (METTL3/14 complex) to modify Xist itself, a step crucial for its function [6] [8].

- Repeats B/C: These regions are vital for stabilizing the silent state. They recruit HNRNPK, which mediates the recruitment of the non-canonical Polycomb Repressive Complex 1 (PRC1). PRC1 catalyzes the ubiquitination of histone H2A at lysine 119 (H2AK119ub), a key repressive mark [6].

- Repeats A/E: These repeats are essential for accumulating proteins with intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs), facilitating the formation of Xist condensates via liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS). This process is thought to create functional gradients of silencing factors across the X chromosome [6].

Table 1: Key Functional Repeats of Xist RNA and Their Protein Partners

| Xist Repeat | Key Recruited Proteins | Primary Function in XCI | Major Chromatin Modifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| A (RepA) | SPEN (SHARP), RBM15 | Initiation of gene silencing | Histone deacetylation, m6A RNA modification |

| B/C | HNRNPK | Stabilization of silencing | H2AK119ub (by PRC1) |

| A/E | IDR-containing proteins | Formation of silencing condensates (LLPS) | Establishment of repressive nuclear compartments |

A recent genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 screen has expanded the regulatory landscape of XCI by identifying several microRNAs (miRNAs) as novel regulators. Among the top candidates, miR106a was found to physically interact with the RepA region of Xist. Loss of miR106a leads to the dissociation and destabilization of Xist, interfering with XCI maintenance. This finding has direct therapeutic implications, as inhibition of miR106a has been shown to improve pathology in a Rett syndrome model by potentially reactivating the wild-type MECP2 allele on the Xi [8].

Layer 1: Histone Modifications and Chromatin Remodeling

The Xi is characterized by a distinct histone modification landscape that promotes a condensed, heterochromatic state.

Polycomb-Mediated Repression

The recruitment of PRC1 via HNRNPK and Repeats B/C leads to the deposition of H2AK119ub. This mark serves as a beacon for the recruitment of the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2), which catalyzes the trimethylation of histone H3 at lysine 27 (H3K27me3) [6]. These two Polycomb group complexes often co-localize, creating stable Polycomb chromatin domains that are a hallmark of the facultative heterochromatin on the Xi [6].

Additional Chromatin Factors

The protein SMCHD1 accumulates on the Xi several days after Xist induction. Its recruitment depends on H2AK119ub but not H3K27me3. While not essential for maintaining the silencing of all genes, SMCHD1 is crucial for the stable repression of a specific subset of genes during XCI establishment [6].

Histone Modifications and Nuclear Reorganization

The repressive histone marks contribute to the large-scale structural reorganization of the Xi. The chromosome undergoes compaction and repositioning to the nuclear periphery or to the nucleolus, further reinforcing the transcriptionally silent state by creating a repressive nuclear environment [6].

Figure 1: Xist-Mediated Recruitment of Repressive Complexes and Establishment of the Xi. The diagram illustrates how different repeats of Xist RNA recruit specific protein partners (SPEN, RBM15, HNRNPK), which in turn recruit effector complexes (HDACs, m6A machinery, PRC1) that establish a multi-layered repressive chromatin environment on the X chromosome.

Layer 2: DNA Methylation

DNA methylation provides a stable, long-term layer of epigenetic silencing on the Xi, working in concert with histone modifications.

Molecular Basis and Dynamics

DNA methylation in mammals primarily involves the addition of a methyl group to the 5' carbon of cytosine within CpG dinucleotides (5-methylcytosine, 5mC), catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) [17]. The establishment of DNA methylation patterns during gametogenesis and early embryogenesis involves waves of global demethylation followed by de novo methylation, driven by DNMT3A and DNMT3B with the cofactor DNMT3L. DNMT1 then maintains these patterns during DNA replication [17]. During spermatogenesis, DNA methylation dynamics are tightly regulated, with levels increasing during the transition from undifferentiated to differentiating spermatogonia and reaching a high level in pachytene spermatocytes [17].

Role in XCI and Genomic Distribution

DNA methylation is intricately involved in XCI, particularly in the stable silencing of gene promoters on the Xi [18]. The distribution of DNA methylation is not uniform. A comprehensive study analyzing 9,777 CpGs on the X chromosome in blood samples from over 4,000 individuals found that age-related changes in DNA methylation on the Xi are dominated by an accumulation of variability (aVMCs) rather than consistent differences in mean methylation levels. These aVMCs were enriched in CpG islands and regions subject to XCI, suggesting a progressive loss of epigenetic fidelity on the Xi with age in females [18].

Table 2: DNA Methyltransferases (DNMTs) and Their Roles

| Enzyme | Type | Function | Phenotype of Loss-of-Function in Male Germ Cells |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNMT1 | Maintenance | Methylates hemimethylated CpG sites on nascent DNA strands | Apoptosis of germline stem cells; hypogonadism and meiotic arrest [17] |

| DNMT3A | De novo | Establishes new DNA methylation patterns during embryogenesis and gametogenesis | Abnormal spermatogonial function [17] |

| DNMT3B | De novo | Works with DNMT3A to establish DNA methylation patterns | Fertility with no distinctive phenotype [17] |

| DNMT3C | De novo | Rodent-specific methyltransferase | Severe defect in DSB repair and homologous chromosome synapsis during meiosis [17] |

| DNMT3L | Cofactor | Enhances the activity of DNMT3A/B | Decrease in quiescent spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs) [17] |

Layer 3: Nuclear Reorganization and Phase Separation

Beyond biochemical modifications, the Xi undergoes profound physical reorganization within the nucleus.

The Barr Body and Nuclear Compartmentalization

The Xi condenses into a compact structure known as the Barr body, which is typically localized at the nuclear periphery or adjacent to the nucleolus [6]. This spatial segregation positions the Xi within a transcriptionally repressive nuclear environment, limiting its access to the transcriptional machinery present in the nuclear interior.

Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation (LLPS)

Emerging evidence underscores the significance of molecular crowding, most likely via liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS), in the formation of Xist RNA-driven condensates [6]. These biomolecular condensates are critical for establishing and sustaining the silenced state. The process is driven by transient homotypic and heterotypic interactions between Xist RNA and proteins containing intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs), which are recruited by Repeats A/E of Xist [6]. These condensates are thought to create a concentrated hub of repressive complexes, facilitating efficient and stable silencing across the X chromosome. While LLPS is a leading model, other mechanisms like polymerization-induced microphase separation or gelation may also contribute to the biophysical properties of the Xi [6].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Studying the multi-layered epigenetics of the Xi requires a combination of sophisticated genomic, cellular, and computational techniques.

Mapping XCI Status and Ratios in Populations

Bulk RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) from tissues can be used to estimate XCI ratios at a population level. This approach leverages natural genetic variation (heterozygous single nucleotide polymorphisms, SNPs) to measure allele-specific expression (ASE). A folded-normal distribution is fitted to the reference allelic expression ratios of multiple X-linked SNPs per sample to estimate the XCI ratio magnitude, which can then be unfolded to generate population-level distributions [16]. This method has been successfully applied to data from over 9,500 individual samples across 10 mammalian species, revealing that embryonic stochasticity is a general explanatory model for population XCI variability [16].

Modeling XCI in Stem Cells

Mouse and human embryonic stem cells (ESCs and hiPSCs) provide powerful in vitro models for studying XCI. The Momiji ESC system (version 2) is a particularly robust tool that enables live imaging of random XCI. This system uses female ESCs where each X chromosome carries distinct fluorescent reporters and drug-resistance markers. Drug selection before differentiation prevents X-chromosome loss, enabling faithful modeling and long-term single-cell live imaging of XCI onset and progression for up to 7 days using spinning-disk confocal microscopy [19]. Studies in hiPSCs have revealed that XCI erosion is a common occurrence, characterized by the loss of XIST expression and a non-random, gradual reactivation of genes, particularly those known to escape XCI in human tissues [20].

Functional Genomic Screens

Genome-wide loss-of-function CRISPR/Cas9 screens have been instrumental in identifying novel regulators of XCI. A typical screen involves transducing a female fibroblast cell line (which carries a selectable reporter gene, such as Hprt, only on the Xi) with a sgRNA library. Cells are then placed under selection (e.g., HAT media), and sgRNAs that enable survival by disrupting XCI and reactivating the Xi-linked reporter are identified through sequencing [8]. This approach has recently uncovered a role for specific nuclear-enriched miRNAs, like miR106a, in maintaining XCI stability [8].

Figure 2: Key Experimental Workflows for Studying XCI. The diagram summarizes three major approaches: (1) CRISPR screens in fibroblasts to identify regulators, (2) live imaging in engineered ESCs to track dynamics, and (3) computational analysis of bulk RNA-seq data from tissues to determine XCI ratios in populations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for XCI Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Momiji ESC System (v2) | Live imaging of random XCI dynamics in vitro | Dual fluorescent reporters and drug-resistance markers on each X chromosome; prevents X loss [19] |

| CRISPR/Cas9 sgRNA Libraries | Genome-wide loss-of-function screens to identify XCI regulators | Enables discovery of novel factors like miRNAs (e.g., miR106a) [8] |

| XIST-Specific FISH Probes | Visualizing Xist RNA coating and Xi nuclear positioning | Critical for confirming Xist localization and Barr body formation [6] |

| Allele-Specific RNA-seq | Quantifying XCI ratios and identifying genes that escape silencing | Requires heterozygous SNPs; can be applied to bulk tissue or single cells [16] [20] |

| Antibodies against Histone Marks | Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) to map repressive domains on Xi | Key targets: H3K27me3 (PRC2), H2AK119ub (PRC1) [6] |

| Differentiated hiPSCs | Modeling human XCI and its erosion in a relevant cellular context | Retains somatic XCI pattern; shows clonality but prone to XIST loss and erosion [20] |

| Abacavir | Abacavir|Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitor | Abacavir is a nucleoside analog for HIV research. It inhibits reverse transcriptase. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Mangafodipir Trisodium | Mangafodipir Trisodium, CAS:140678-14-4, MF:C22H27MnN4Na3O14P2, MW:757.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The epigenetic silencing of the X chromosome is a multi-layered process, integrating the RNA-based orchestration of Xist, a cascade of repressive histone modifications, the stable lock of DNA methylation, and the profound biophysical reorganization of the chromosome into a condensed, phase-separated nuclear compartment. Disruptions in this elaborate system are linked to male infertility through faulty spermatogenesis [17] and to X-linked disorders in females [8].

Future research will continue to dissect the precise mechanisms of LLPS in XCI and its interplay with traditional chromatin modifiers. Furthermore, the emergence of epigenome editing technologies offers a transformative approach for clinical treatment, enabling precise modifications to gene expression without altering the DNA sequence [21]. The discovery of novel regulatory nodes, such as the miR106a-Xist axis, opens new avenues for therapeutic intervention. As demonstrated in Rett syndrome models, targeting these nodes to selectively reactivate genes on the Xi holds immense promise for treating a range of X-linked monogenic disorders [8]. The intricate epigenetic layers of the inactive X chromosome thus continue to serve as a rich model system for fundamental gene regulation and a beacon for developing novel epigenetic therapies.

X-chromosome inactivation (XCI) represents a fundamental paradigm of epigenetic regulation in female mammals, serving as the quintessential dosage compensation mechanism to balance X-linked gene expression between XX females and XY males [22]. This process, initiated early in embryonic development, results in the formation of a transcriptionally silent inactive X chromosome (Xi), characterized by a distinct heterochromatic state mediated by the long non-coding RNA XIST, DNA methylation, and repressive histone modifications [23] [22]. However, decades of research have revealed that this silencing is remarkably incomplete. Approximately 15-30% of X-chromosomal genes escape XCI and are expressed from both the active (Xa) and inactive (Xi) X chromosomes in female cells [23] [22]. This escape from XCI creates a state of natural biallelic expression that contributes to sexual dimorphism in gene expression and may underlie the pronounced female bias observed in many autoimmune and immune-mediated diseases [9] [22]. Understanding the mechanisms, patterns, and functional consequences of escape from XCI is therefore critical for comprehending female-specific disease susceptibility and developing targeted therapeutic interventions.

The Epigenetic Landscape of Escape from XCI

Defining Epigenetic Heterogeneity at the Xi

The incomplete silencing of the X chromosome manifests through distinct epigenetic signatures that differentiate escape genes from their inactivated counterparts. Genes subject to complete XCI typically display enrichment of heterochromatic marks such as H3K27me3 and H3K9me3 on the Xi, coupled with depletion of euchromatic marks including H3K27ac, H3K4me2, and H3K4me3 [23]. In contrast, genes that escape XCI demonstrate an intermediate epigenetic state on the Xi, retaining certain active histone modifications while lacking the full complement of repressive marks found at silenced loci [23]. DNA methylation patterns at promoter CpG islands further distinguish these categories: escape genes typically exhibit low methylation on both Xa and Xi, while inactivated genes show differential methylation with the Xi being highly methylated [23] [24]. This epigenetic heterogeneity is not uniformly distributed across the X chromosome; escape genes tend to cluster in specific regions, particularly near the pseudoautosomal regions (PARs) and on the short arm of the X chromosome, while the long arm is enriched for genes subject to XCI [23].

Classification and Prevalence of Escape Genes

Escape genes are categorized based on their consistency of expression patterns across individuals and tissues:

Table: Classification of X-Chromosome Inactivation Status Categories

| Category | Prevalence | Definition | Epigenetic Features on Xi |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constitutive Escape | ~12% of X genes | Consistently escape XCI in all tissues and individuals | Retained euchromatic marks (H3K4me3, H3K27ac); depleted heterochromatic marks |

| Variable/Facultative Escape | ~8% of X genes | Escape XCI in only certain tissues or individuals | Intermediate epigenetic state with tissue-specific modulation |

| Subject to XCI | ~65% of X genes | Completely silenced on Xi in all contexts | Enriched heterochromatic marks (H3K27me3, H3K9me3); depleted euchromatic marks |

| Discordant | ~7% of X genes | Inconsistent classification between studies | Unclear or conflicting epigenetic patterns |

Recent multi-tissue analyses have substantially refined our understanding of escape gene prevalence. A comprehensive study integrating data from non-mosaic XCI females across 30 human tissues directly determined XCI status for 380 X-linked genes, providing the most extensive reference map of human X-inactivation to date [25]. This research confirmed that escape from XCI is not merely an aberration but a widespread phenomenon affecting nearly a quarter of assessed genes, with tissue-specific escape patterns adding another layer of complexity to X-chromosomal regulation [26] [25].

Methodological Approaches for Studying XCI Escape

Gold-Standard and Emerging Technologies

The accurate assessment of XCI status presents significant methodological challenges, primarily due to the mosaic nature of XCI in female tissues. Conventional approaches have relied on clonal cell populations or naturally skewed tissues to distinguish parental alleles, but these methods are limited by availability and potential confounding factors [23]. The historical gold standard for XCI analysis utilizes Methylation-Sensitive Restriction Enzymes (MSREs) followed by PCR and Fragment Length Analysis (FLA) of polymorphic repeats in genes such as the androgen receptor (AR) and X-linked retinitis pigmentosa 2 (RP2) [24]. However, this approach investigates only one or two CpG sites per gene and suffers from technical limitations including PCR stutter peaks and amplification biases [24].

Recent technological advances have revolutionized the field by enabling comprehensive, quantitative analysis of XCI escape patterns:

XCI-ONT (Oxford Nanopore Technologies): This novel approach utilizes amplification-free Cas9 enrichment of target regions followed by long-read sequencing to simultaneously detect methylation patterns across hundreds of CpG sites and identify parental alleles through natural repeat polymorphisms [24]. Unlike the gold-standard method, XCI-ONT interrogates 116 CpGs in AR and 58 CpGs in RP2, providing a robust quantitative assessment of XCI ratios without PCR bias [24]. The method demonstrates superior accuracy in quantifying intermediate levels of XCI skewing (e.g., 95:5, 97:3) that are poorly resolved by conventional techniques [24].

scLinaX (Single-Cell Lineage and XCI): Developed specifically for droplet-based single-cell RNA sequencing data, this computational tool directly quantifies relative gene expression from the Xi by leveraging natural genetic variation [27]. The algorithm enables cell-type-specific analysis of escape from XCI and has revealed striking differences in escape patterns between lymphocyte and myeloid cell populations [27]. An extension to multiome datasets (scLinaX-multi) further permits correlation of escape patterns with chromatin accessibility profiles [27].

Allelic Expression Analysis in Non-Mosaic XCI Females: The identification of females with completely skewed (non-mosaic) XCI across all tissues provides a powerful natural system for directly determining XCI status from bulk tissue samples [25]. By analyzing allele-specific expression in these rare individuals across multiple tissues, researchers have established comprehensive maps of XCI escape without the confounding effects of cellular mosaicism [26] [25].

Experimental Workflow for Comprehensive XCI Analysis

The following diagram illustrates an integrated experimental workflow for analyzing escape from XCI, combining both established and cutting-edge methodologies:

Integrated Workflow for XCI Escape Analysis

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for XCI Studies

| Category | Specific Reagents/Resources | Application/Function |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Models | Clonal cell lines, non-mosaic XCI female samples, hybrid cell systems | Provide defined systems for allelic expression analysis without mosaicism complications |

| Molecular Biology | Methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes (HpaII, HhaI), bisulfite conversion kits, Cas9-gRNA complexes for enrichment | Target-specific analysis of DNA methylation patterns and parental allele discrimination |

| Sequencing Platforms | Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) platforms, 10x Genomics single-cell solutions, Illumina bisulfite sequencing | Long-read methylation-aware sequencing; single-cell transcriptomic and epigenomic profiling |

| Bioinformatic Tools | scLinaX, Nanopolish, allelic expression pipelines, XCI status predictors | Quantification of escape from single-cell data; methylation calling; XCI status prediction from epigenetic marks |

| Epigenetic Reagents | Antibodies for H3K27me3, H3K4me3, H3K27ac, H3K9me3, DNA methylation arrays | Chromatin immunoprecipitation; genome-wide methylation profiling to characterize Xi chromatin state |

| Reference Databases | GTEx dataset, IHEC epigenome maps, Balaton et al. 2015 XCI compendium | Benchmarking and validation using established XCI status calls across multiple tissues |

Biological Implications and Clinical Relevance

Immune Function and Female-Bias in Autoimmunity

The escape from XCI has profound implications for immune system function and provides a plausible mechanistic explanation for the strong female bias observed in many autoimmune conditions. Critical pattern recognition receptors encoded on the X chromosome, including TLR7 and TLR8, have been identified as escape genes in specific immune cell populations [9]. In plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs), which are pivotal producers of type I interferons, escape-mediated overexpression of these TLRs creates hyperresponsive subsets that preferentially expand in autoimmune contexts such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and systemic sclerosis (SSc) [9]. The resulting enhancement of nucleic acid sensing and IFN-α production establishes a feed-forward loop of immune activation and tissue damage that drives disease pathogenesis [9]. This model is supported by observations that males with Klinefelter syndrome (XXY) display similar susceptibility to female-biased autoimmune diseases as XX females, highlighting the contribution of X chromosome number rather than hormonal differences [9].

Tissue and Cell-Type Specificity of Escape Patterns

Recent single-cell and multi-tissue analyses have revealed that escape from XCI is not a uniform phenomenon but exhibits remarkable tissue and cell-type specificity. The scLinaX tool applied to large-scale blood scRNA-seq datasets demonstrated stronger escape in lymphocytes compared to myeloid cells, suggesting lineage-specific differences in XCI maintenance [27]. Furthermore, analysis of human multiple-organ scRNA-seq data identified relatively strong degrees of escape from XCI in lymphoid tissues and lymphocytes compared to other cell types [27]. Tissue-specific escape patterns have also been documented, with genes such as KAL1 escaping XCI exclusively in lung tissue [26]. This cellular and tissue heterogeneity in escape patterns has significant implications for understanding the tissue-specific manifestations of X-linked disorders and developing targeted treatment approaches.

Implications for X-Linked Diseases and Female Manifestation

Escape from XCI directly influences the penetrance and expressivity of X-linked disorders in female carriers. In X-linked conditions such as Fabry disease, caused by mutations in the GLA gene encoding α-galactosidase A, the direction and degree of XCI skewing significantly impact clinical presentation [22]. Female carriers with preferential inactivation of the mutant allele typically present with milder symptoms, while those expressing the mutant allele due to escape or skewed XCI develop more severe disease manifestations [22]. However, the relationship is not absolute, as some severely affected females show random XCI patterns in accessible tissues like leukocytes, highlighting the limitation of analyzing tissues that may not reflect affected organs [22]. For X-linked diseases where male hemizygotes are prenatally lethal, including Cornelia de Lange 2 (SMC1A truncating variants) and CHILD syndrome, escape from XCI or selective survival of cells expressing the wild-type allele enables female survival while still resulting in disease manifestations [22].

The study of genes that escape X-chromosome inactivation has evolved from documenting exceptional cases to recognizing a fundamental aspect of X-chromosome biology with far-reaching implications for sexual dimorphism, disease susceptibility, and therapeutic development. The ongoing development of sophisticated experimental approaches—including single-cell multi-omics, long-read methylation-aware sequencing, and computational tools for allelic expression analysis—promises to further unravel the complexity of this regulatory phenomenon. Future research directions should focus on elucidating the dynamic regulation of escape during development and disease progression, understanding the three-dimensional chromatin architecture of the Xi, and developing therapeutic strategies that account for or modulate escape behavior. As our technical capabilities advance, so too will our understanding of how the incomplete silencing of the X chromosome shapes human health and disease.

X-chromosome inactivation (XCI) is a fundamental epigenetic process in female therian mammals that ensures dosage compensation by transcriptionally silencing one of the two X chromosomes. This review examines the substantial species-specific variations in XCI mechanisms and outcomes across mammalian species, with particular focus on human and mouse models. The evolution of sex chromosomes from an ancestral autosomal pair began with the emergence of a sex-determining mutation, leading to progressive recombination suppression and Y chromosome degradation [28] [29]. This evolutionary process created distinct "evolutionary strata" on the X chromosome, reflecting successive recombination suppression events [28]. As a consequence, different mammalian lineages have developed varied XCI strategies, including differences in the key regulatory long non-coding RNAs, the distribution and percentage of genes that escape silencing, and the chromatin remodeling mechanisms involved. Understanding these species-specific variations is critical for interpreting model organism data in the context of human disease and for developing targeted epigenetic therapies for X-linked disorders.

Molecular Mechanisms of XCI: Conserved Factors and Species-Specific Adaptations

Core Silencing Machinery: XIST and RSX

The initiation of XCI is governed by long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), with XIST (X-inactive specific transcript) serving as the master regulator in placental mammals (eutherians) [30] [31]. XIST RNA coats the future inactive X chromosome (Xi) in cis, triggering a cascade of chromatin modifications that lead to stable silencing [31] [12]. The Xist gene contains multiple conserved repeat domains (A-F) that serve as functional modules for protein binding and silencing activities [30]. For example, the A-repeat is essential for gene silencing and recruits transcriptional repressors like SPEN, while B and C repeats facilitate polycomb recruitment and repressive histone mark deposition (H2AK119Ub and H3K27me3) [30].

In marsupials, which lack XIST, a functionally analogous but evolutionarily independent lncRNA called RSX (RNA on the silent X) coordinates XCI [30]. Despite having no sequence similarity to XIST, RSX contains tandem repeat domains that may recruit similar protein partners, representing a striking case of convergent evolution for dosage compensation [30].

Table 1: Key Long Non-Coding RNAs in X-Chromosome Inactivation

| lncRNA | Species Distribution | Origin | Key Functional Domains | Primary Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XIST | Placental mammals | Evolved from LNX3 protein-coding gene after divergence from marsupials | Repeats A-F (A essential for silencing) | cis-chromosome coating; recruitment of repressive complexes; initiation of silencing |

| RSX | Marsupials | Independent evolutionary origin | Repeats 1-4 (functional similarity to XIST repeats) | Marsupial XCI initiation; functional analog of XIST |

| TSIX | Placental mammals (well-characterized in mouse) | Antisense to XIST | Overlaps XIST locus | Antagonizes XIST expression; protects active X from silencing |

Chromatin Architecture and 3D Genome Organization

Recent research has highlighted the significance of three-dimensional genome architecture in XCI establishment and maintenance. The CTCF protein, a master regulator of chromatin looping, plays a particularly important role in defining boundaries that protect certain genes from silencing [32]. At the Car5b locus in mice, CTCF binding sites create insulated chromatin loops that prevent the spread of repressive chromatin marks into escape domains [32]. Experimental evidence demonstrates that deletion (but not inversion) of these CTCF sites abolishes escape by allowing heterochromatic marks like H3K27me3 to invade the Car5b locus [32]. This insulation mechanism varies between species and contributes to the observed differences in escape gene distribution.

Diagram 1: CTCF-mediated insulation model. CTCF binding sites form a chromatin loop that protects escape genes (e.g., Car5b) from repressive chromatin marks that silence neighboring genes.

Species Variations in XCI Patterns and Outcomes

Escape from X Inactivation: Human vs. Mouse

A striking difference between species is observed in the pattern and prevalence of genes that escape XCI. These "escapees" remain transcriptionally active from both the active (Xa) and inactive (Xi) X chromosomes in female cells, potentially contributing to sex-specific differences in gene dosage and disease susceptibility [33].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of XCI Escape in Humans and Mice

| Feature | Human | Mouse | Biological Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of Escape Genes | 15-30% of X-linked genes [32] [33] | 3-7% of X-linked genes [32] [33] | Greater X-linked gene dosage differences in human females |

| Genomic Distribution | Clustered in large domains (100 kb to 7 Mb); predominantly on Xp [33] | Mostly single genes embedded in silenced chromatin; random distribution [33] | Different regulatory mechanisms; positional effects in humans |

| Relationship to Y Homology | Many escapees have lost Y counterparts [33] | Most escapees retain Y homologs [28] | Different evolutionary constraints and dosage sensitivity |

| Impact of X Monosomy | Severe Turner syndrome (45,X) phenotypes [33] | Mild phenotypes; fertile X0 females [33] | Human-specific escape genes may contribute to Turner syndrome |

The mechanisms underlying these species differences are multifaceted. In humans, the concentration of escape genes on the short arm (Xp) may reflect its more recent divergence from the Y chromosome [33]. Additionally, centromeric heterochromatin in humans might act as a barrier that limits the spread of XIST RNA, which is transcribed from the long arm (Xq) [33]. In contrast, the mouse X chromosome has a terminal centromere, potentially allowing more uniform spread of silencing factors.

Marsupials and Monotremes: Alternative XCI Strategies

Beyond human and mouse models, other mammalian lineages exhibit distinct XCI patterns. Marsupials utilize RSX rather than XIST for XCI and display imprinted XCI exclusively, where the paternal X is always silenced [30] [31]. Marsupial XCI is also characterized by incomplete and tissue-specific silencing of some X-linked genes [33].

Monotremes (platypus and echidna) represent an even more ancestral system, with a complex sex chromosome system comprising multiple X and Y chromosomes (Xâ‚-Xâ‚… and Yâ‚-Yâ‚…) that are not homologous to therian sex chromosomes [28]. The mechanisms of dosage compensation in monotremes remain poorly understood but likely involve different strategies altogether [28].

Experimental Approaches for Investigating XCI

Key Methodologies and Workflows

Advanced genomic techniques have been essential for dissecting the molecular mechanisms of XCI and its species-specific variations. The following workflow outlines a comprehensive approach for allele-specific analysis of XCI status:

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for allele-specific analysis of XCI. This integrated approach enables precise determination of gene silencing and escape patterns.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for XCI Studies

| Reagent/Technology | Function in XCI Research | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Interspecific Hybrid Cells | Provides polymorphic sites for allele-specific analysis [33] | Mapping Xi vs. Xa transcript origin; identifying escape genes |

| So-Smart-Seq | Captures comprehensive transcriptome (polyA+ and polyA- RNAs) [34] | Profiling repetitive elements; analyzing early embryonic XCI |

| Allele-Specific RNA-Seq | Quantifies expression from each X chromosome independently [33] | Determining XCI status at single-gene resolution |

| XIST-inducible Systems | Controlled induction of XCI in embryonic stem cells [12] | Studying initiation and kinetics of silencing |

| ChIP-seq/CUT&RUN | Maps protein-DNA interactions and histone modifications [32] | Defining repressive chromatin marks on Xi; CTCF binding |

| Hi-C/3D Genome Mapping | Captures chromosome conformation and spatial organization [32] | Analyzing topological domains and insulation boundaries |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Genome Editing | Targeted manipulation of regulatory elements [32] | Validating function of CTCF sites, XIST repeats |

| Rocuronium | Rocuronium, CAS:143558-00-3, MF:C32H53N2O4+, MW:529.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Elacridar | Elacridar, CAS:143664-11-3, MF:C34H33N3O5, MW:563.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Research Applications and Therapeutic Implications

Modeling X-Linked Diseases and Sex-Biased Expression

The species-specific differences in XCI patterns have profound implications for modeling human diseases. The higher percentage of escape genes in humans means that X-linked disorders often manifest differently in females than males, with variable expression depending on XCI patterns and skewing [32]. For conditions like Rett syndrome (caused by MECP2 mutations), the random nature of XCI results in mosaic expression of the healthy allele in female patients [35]. This mosaicism contributes to the variable severity of symptoms observed in affected girls.

Recent therapeutic approaches have leveraged knowledge of XCI mechanisms to develop novel treatments. For example, targeting microRNA-106a with a "sponge" decoy molecule can reactivate the silent X chromosome carrying a healthy MECP2 copy in Rett syndrome models, demonstrating significant symptom improvement [35]. This approach highlights the potential for X-reactivating therapies for various X-linked disorders.

Transposable Elements and Their Regulation

Beyond protein-coding genes, recent research has investigated the fate of transposable elements (TEs) during XCI. A 2025 study developed a specialized bioinformatic pipeline for allele-specific analysis of repetitive elements and found that X-linked TEs show dynamic regulation during development, with significant differences in silencing between imprinted and random XCI [34]. However, unlike coding genes, TEs do not undergo X-chromosome upregulation (XCU), suggesting distinct regulatory mechanisms for different genomic elements [34].

The comparative analysis of XCI across mammalian species reveals both conserved principles and remarkable diversity in epigenetic regulatory mechanisms. The differences between humans and mice in escape gene number, distribution, and regulation underscore the importance of considering species-specific contexts when interpreting experimental findings, particularly for preclinical studies of X-linked diseases. Future research directions should include developing more sophisticated humanized mouse models that better recapitulate human XCI patterns, exploring the mechanistic basis of tissue-specific escape, and advancing X-reactivating therapeutic strategies for X-linked disorders. The continued integration of evolutionary perspectives with mechanistic studies will undoubtedly yield further insights into this fascinating epigenetic phenomenon and its role in health and disease.

Tools of the Trade: Profiling the Inactive X Chromosome

X-chromosome inactivation (XCI) is a quintessential epigenetic process in female mammals that ensures dosage compensation by transcriptionally silencing one of the two X chromosomes [36]. The precise determination of which genes are silenced, which remain active, and to what extent, is fundamental to understanding female development, cellular mosaicism, and sex-biased diseases. Among the various methods developed to assess XCI status, allelic expression analysis stands as the gold standard approach [37]. This technique directly measures expression from each parental X chromosome allele, providing unambiguous evidence of inactivation status without relying on proxy epigenetic marks or comparative inferences.

The primacy of allelic expression analysis stems from its ability to directly observe the functional outcome of XCI—the transcriptional silencing of one allele—at individual genetic loci. While epigenetic marks like DNA methylation and histone modifications are strongly correlated with silencing status, they represent the mechanism rather than the consequence [37] [38]. Similarly, approaches that infer XCI status from sex-biased expression patterns or male-female comparisons provide indirect evidence that can be confounded by other biological variables [25]. Allelic expression analysis transcends these limitations by enabling direct quantification of expression imbalance between the active X (Xa) and inactive X (Xi) within the same cellular context, providing definitive evidence for whether a gene is subject to inactivation, escapes inactivation entirely, or exhibits variable escape across tissues or individuals [25] [37].

This technical guide examines the methodological foundations, experimental implementations, and analytical frameworks of allelic expression analysis for XCI status determination, positioning this approach within the broader context of epigenetic regulation research with particular relevance for drug discovery and therapeutic development for X-linked disorders.

Theoretical Foundations: Principles of Allelic Expression Analysis

Biological Basis and Technical Rationale

The fundamental principle underlying allelic expression analysis is the detection of allelic imbalance in transcript abundance resulting from monoallelic expression. In the context of XCI, genes subject to inactivation will demonstrate expression predominantly or exclusively from the single active X chromosome, while genes escaping inactivation will show biallelic expression with approximately equal contribution from both X chromosomes [25]. This expression imbalance can be quantified by identifying heterozygous single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within X-linked genes and measuring the relative abundance of each allele in RNA sequencing data [39].