CRISPR-dCas9 Epigenetic Editing: A Comprehensive Guide for Functional Validation in Biomedical Research

This article provides a detailed overview of CRISPR-dCas9-based epigenetic editing for the functional validation of genetic targets.

CRISPR-dCas9 Epigenetic Editing: A Comprehensive Guide for Functional Validation in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a detailed overview of CRISPR-dCas9-based epigenetic editing for the functional validation of genetic targets. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of using catalytically dead Cas9 fused to epigenetic modifiers like Tet1 and p300 to precisely manipulate gene expression without altering the DNA sequence. The scope extends from core mechanisms and diverse methodological applications to critical troubleshooting for minimizing off-target effects and rigorous validation strategies. By synthesizing current research and comparative analyses, this guide serves as a resource for leveraging epigenetic editing to deconvolute disease mechanisms, identify novel drug targets, and advance therapeutic development.

Demystifying the Core Principles: From CRISPR-Cas9 to Epigenome Editing

The repurposing of the native, DNA-cleaving Cas9 (CRISPR-associated protein 9) into a nuclease-deactivated Cas9 (dCas9) represents a foundational shift in the capabilities of CRISPR technology. By introducing point mutations (D10A and H840A for Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9) to inactivate the RuvC and HNH nuclease domains, researchers transformed a precise molecular scissor into a versatile, programmable DNA-binding platform [1] [2]. This evolution has unlocked a new realm of applications that move beyond permanent gene knockout towards the reversible and precise control of gene expression and epigenetic states, a capability of paramount importance for functional validation research in drug discovery.

This shift is encapsulated by the emergence of the "CRISPR-Epigenetics Regulatory Circuit," a model highlighting the bidirectional relationship where dCas9 systems can rewrite epigenetic states, and the pre-existing epigenetic landscape, in turn, influences the efficiency of dCas9 binding and function [1]. This paradigm is central to using dCas9 for functional genomics, as it allows researchers to probe the causal relationships between epigenetic marks, gene expression, and cellular phenotypes without altering the underlying DNA sequence, thereby providing a powerful tool for validating disease-relevant gene targets.

The dCas9 Toolkit: From Transcriptional to Epigenetic Control

The core dCas9 protein serves as a scaffold that can be fused to a diverse array of effector domains, enabling multifaceted control over genomic function. The primary applications fall into three key categories:

- CRISPR Interference (CRISPRi): dCas9 fused to transcriptional repressor domains like the KRAB (Krüppel-associated box) domain silences target gene expression by inducing heterochromatin formation [2].

- CRISPR Activation (CRISPRa): dCas9 fused to transcriptional activators such as VP64, p65, or Rta (VPR system) or recruited to more complex systems like the Synergistic Activation Mediator (SAM), upregulates endogenous gene expression [3] [2].

- Epigenetic Editing (Epi-CRISPR): dCas9 targeted to specific loci can rewrite the local epigenetic code. For example, fusions with the TET1 demethylase catalyze DNA demethylation to activate genes, while fusions with DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) or histone modifiers (e.g., p300) can introduce repressive or activating marks, respectively [4] [1].

Table 1: Core dCas9 Systems for Functional Genomics

| System | Key Effector Domains | Primary Function | Main Application in Functional Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPRi | dCas9-KRAB | Transcriptional Repression | Gene knockdown studies; essential gene validation |

| CRISPRa | dCas9-VP64, dCas9-SAM, dCas9-VPR | Transcriptional Activation | Gain-of-function screens; target gene validation |

| Epi-CRISPR | dCas9-TET1, dCas9-p300, dCas9-DNMT3A | Targeted DNA Demethylation/Methylation | Causal link between epigenetic state and gene expression |

| Goserelin Acetate | Goserelin Acetate, CAS:145781-92-6, MF:C61H88N18O16, MW:1329.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Amastatin hydrochloride | Amastatin hydrochloride, CAS:100938-10-1, MF:C21H39ClN4O8, MW:511.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

These systems form the basis of perturbomics, a functional genomics approach that systematically annotates gene function by observing phenotypic changes resulting from targeted perturbations, with dCas9-based CRISPR screens becoming the method of choice for this purpose [2].

Application Note 1: Targeted Reactivation of a Tumor Suppressor via Epigenetic Editing

Objective and Rationale

A common hallmark of cancer is the epigenetic silencing of tumor suppressor genes via promoter hypermethylation. This protocol outlines the use of a CRISPR/dCas9-TET1 system to reactivate the tumor-suppressive microRNA, miR-200c, which is frequently silenced in aggressive breast cancer cells and is a key regulator of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [4].

Experimental Workflow and Protocol

Step 1: gRNA Design and Vector Construction

- gRNA Design: Design two sgRNAs to flank the CpG-rich region of the miR-200c promoter (e.g., within -343 to -115 bp upstream of the transcription start site). Use tools like CHOPCHOP for design and off-target prediction [4].

- Vector Construction: Clone the sgRNA sequences into a plasmid containing the dCas9-TET1 fusion protein. Validate all constructs using colony PCR and Sanger sequencing (see Fig. 2 in the original study) [4].

Step 2: Cell Transfection and Delivery

- Cell Lines: Use appropriate cancer cell models (e.g., MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer lines).

- Transfection: Transfect cells with the dCas9-TET1 construct along with one or both sgRNAs. A control group should be transfected with a catalytically inactive mutant (dCas9Mut-TET1). Transfection efficiency can be monitored using a co-delivered GFP reporter vector [4].

Step 3: Validation of Epigenetic and Transcriptional Changes

- DNA Methylation Analysis: 48 hours post-transfection, extract genomic DNA. Perform bisulfite sequencing or methylation-specific PCR for the targeted region to quantify demethylation efficiency.

- Gene Expression Analysis: Extract total RNA and measure miR-200c expression levels using RT-qPCR. Co-transfection with both sgRNAs has been shown to have a synergistic effect on reactivation [4].

Step 4: Functional Phenotypic Assays

- Downstream Target Analysis: Evaluate the expression of miR-200c target genes (e.g., ZEB1, ZEB2, KRAS) via RT-qPCR or Western blot to confirm functional restoration of the pathway.

- Cell Viability Assay: Perform an MTT assay to assess the impact of miR-200c reactivation on cell proliferation.

- Apoptosis Assay: Use Annexin V/PI staining and flow cytometry to quantify apoptosis induction. The original study reported an increase in apoptosis from 1.5% (control) to 35.07% in MDA-MB-231 cells [4].

Application Note 2: High-Throughput CRISPRa Screening for Gene Discovery

Objective and Rationale

Gain-of-function (GOF) screens using CRISPRa are powerful for identifying novel genes that control specific cellular processes, such as pluripotency or disease resistance. This protocol details the establishment of a CRISPRa library to identify transcription factors co-regulating the OCT4 gene in pig cells, a methodology adaptable to human drug target discovery [3].

Experimental Workflow and Protocol

Step 1: Library and Reporter Cell Line Engineering

- sgRNA Library Design: Design a library of sgRNAs targeting the promoter regions of transcription factors (e.g., 5,056 sgRNAs for 1,264 factors). Cloning involves synthesizing tandem tRNA–sgRNA sequences into a lentiviral backbone [3].

- Reporter Cell Line Generation: Engineer a stable reporter cell line (e.g., PK15) with a single-copy knock-in of an EGFP reporter gene driven by the OCT4 promoter at a safe-harbor locus (e.g., ROSA26). Also, stably express the dCas9-SAM system in these cells [3].

Step 2: High-Throughput Screening and Hit Identification

- Library Transduction: Transduce the reporter cell population with the sgRNA lentiviral library at a low MOI to ensure most cells receive a single sgRNA.

- Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS): After a suitable expression period, use FACS to isolate the top and bottom percentiles of EGFP-expressing cells (e.g., high vs. low OCT4 activation).

- Hit Deconvolution: Extract genomic DNA from sorted populations, amplify the integrated sgRNA sequences via PCR, and identify enriched or depleted sgRNAs through high-throughput sequencing [3].

Step 3: Validation of Hits

- Individual Validation: Select candidate hits (e.g., MYC, SOX2 as activators; OTX2 as a repressor) and perform individual sgRNA transfections to confirm their specific effect on OCT4-EGFP expression.

- Synergistic Validation: Test combinations of hits (e.g., GATA4 with SALL4) to identify synergistic regulatory relationships [3].

Table 2: Key Reagents for CRISPR/dCas9 Functional Genomics

| Reagent Category | Specific Example | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9 Effector System | dCas9-TET1, dCas9-SAM | Programmable DNA-binding scaffold fused to epigenetic/transcriptional modulators. |

| Delivery Vector | Lentiviral sgRNA library | Enables efficient, stable delivery of sgRNAs for high-throughput screening. |

| Reporter System | OCT4-promoter-EGFP knock-in | Provides a fluorescent readout for target gene activity for easy sorting and quantification. |

| Validation Tools | qPCR primers (ZEB1, ZEB2), MTT assay kit | Validates molecular and phenotypic outcomes post-perturbation. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Considerations

Successful implementation of dCas9-based protocols requires careful selection of core reagents and attention to common experimental hurdles.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for dCas9 Experiments

| Essential Material | Function/Description | Key Considerations for Selection |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9 Effector Plasmid | Expresses the dCas9-effector (e.g., TET1, VP64) fusion protein. | Choose the effector appropriate for the goal (activation, repression, epigenetic editing). Verify nuclear localization signals. |

| sgRNA Expression Vector | Delivers the sequence-specific guide RNA. | For libraries, use lentiviral backbones with selection markers. For single guides, consider tRNA-sgRNA arrays for multiplexing. |

| Lentiviral Packaging System | Produces lentivirus for efficient, stable delivery of sgRNAs/dCas9. | Essential for hard-to-transfect cells and pooled screens. Monitor titer and MOI to ensure single guide delivery. |

| Validated Cell Line Model | The cellular context for the functional assay. | Use reporter lines (e.g., OCT4-EGFP) where possible. Ensure robust expression of dCas9 and sgRNAs. Check epigenetic context of target. |

| Analysis & Validation Kits | Bisulfite sequencing kits, qPCR assays, flow cytometry antibodies. | Use highly specific and sensitive kits for detecting subtle changes in methylation or expression. |

| Enzastaurin | Enzastaurin, CAS:170364-57-5, MF:C32H29N5O2, MW:515.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Tenofovir Disoproxil | Tenofovir Disoproxil|CAS 201341-05-1|RUO | Tenofovir disoproxil is a nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NtRTI) prodrug for HIV and HBV research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human use. |

The transition from DNA-cleaving Cas9 to programmable dCas9 has provided research and drug development professionals with an unparalleled toolkit for functional gene validation. The protocols outlined herein—from targeted epigenetic reactivation of a single tumor suppressor to high-throughput GOF screening—demonstrate the power of dCas9 to establish causal gene-phenotype relationships in a reversible and precise manner.

For successful implementation, researchers must strategically select the dCas9 system (CRISPRi, CRISPRa, or Epi-CRISPR) that best addresses their biological question. Critical success factors include rigorous gRNA design to minimize off-target effects, the use of efficient delivery systems, and a comprehensive validation pipeline that links epigenetic or transcriptional changes to functional phenotypic outcomes. As the field evolves, the integration of these tools with single-cell omics and advanced bioinformatics will further solidify dCas9's role as an indispensable asset for functional genomics and target discovery.

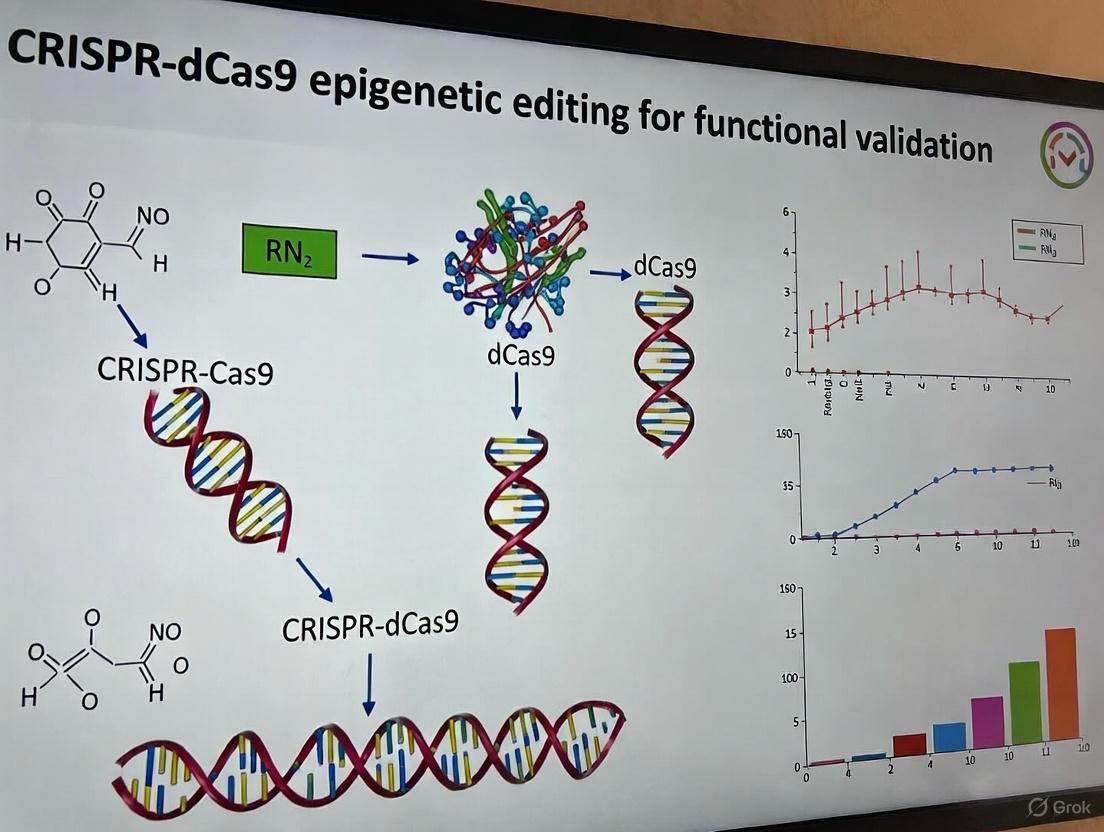

This application note details the functional properties and experimental implementation of two pivotal epigenetic effector domains—Tet1 for DNA demethylation and p300 for histone acetylation—within the context of CRISPR-dCas9 epigenetic editing systems. These tools enable precise, sequence-specific manipulation of the epigenome for functional validation studies in drug discovery and basic research. We provide structured quantitative data, optimized protocols, and visual workflows to facilitate the integration of these effectors into target validation pipelines, allowing researchers to establish causal relationships between epigenetic marks and gene expression outcomes.

Domain Architectures and Functional Mechanisms

TET1: DNA Demethylation Machinery

The Ten-eleven translocation 1 (TET1) protein functions as a DNA demethylase through iterative oxidation of 5-methylcytosine (5mC). Its primary structure features a C-terminal catalytic domain that is essential for its enzymatic activity [5] [6].

- Catalytic Core: The C-terminal domain contains a cysteine-rich region (CRD) and a double-stranded β-helix (DSBH) fold that coordinates Fe(II) and α-ketoglutarate cofactors, which are indispensable for the oxidation reaction [6].

- Mechanism of Action: TET1 initiates the DNA demethylation pathway by converting 5mC to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), then to 5-formylcytosine (5fC), and finally to 5-carboxycytosine (5caC). The latter intermediates (5fC and 5caC) are excised and replaced with unmethylated cytosine via thymine-DNA glycosylase (TDG) and base excision repair (BER) pathways, completing active DNA demethylation [6].

- Targeting Specificity: The natural CXXC zinc finger domain of TET1 confers binding preference for CpG-rich sequences, particularly in gene promoters. In CRISPR-dCas9 applications, this inherent targeting is replaced by the guide RNA programmability [6].

Table 1: TET1 Catalytic Oxidation Pathway Products

| Oxidation Step | Intermediate | Detection Method | Repair Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Oxidation | 5hmC | oxBS-Seq, specific antibodies | Passive dilution through replication |

| Second Oxidation | 5fC | fCAB-Seq | TDG-BER pathway |

| Third Oxidation | 5caC | CAB-Seq | TDG-BER pathway |

p300/CBP: Histone Acetylation Machinery

The histone acetyltransferase p300 (EP300/KAT3B) and its paralog CBP (CREBBP/KAT3A) catalyze lysine acetylation on histone tails, promoting chromatin relaxation and transcriptional activation [7] [8].

- Multidomain Architecture: The catalytic core of p300 contains several functional domains including bromodomain (reader), RING, PHD, and HAT (writer) domains, which cooperate for optimal nucleosome recognition and modification [7].

- Reader-Writer Mechanism: p300 employs a unique mechanism where its bromodomain recognizes existing acetylated marks on histone H4 (specifically H4K12ac/K16ac), directing its catalytic HAT domain to acetylate other histone tails within the same nucleosome, particularly H2B N-terminal tails [7].

- Nucleosome Remodeling: p300-mediated acetylation, especially of H2B N-terminal tails, promotes the dissociation of H2A-H2B dimers, leading to local nucleosome destabilization and facilitating transcription factor access to DNA [7].

- Catalytic Mechanism: p300 operates via a "hit-and-run" (Theorell-Chance) catalytic mechanism where the ternary complex of enzyme, acetyl-CoA, and substrate exists only transiently, with key residues Y1394, D1507, and a conserved water molecule facilitating proton transfer during acetylation [9].

Table 2: p300-Mediated Histone Acetylation Targets and Functional Consequences

| Histone Target | Primary Sites | Chromatin Effect | Transcriptional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| H2B | K11, K12, K15, K16, K20 | Nucleosome destabilization | Enhancer activation |

| H3 | K14, K18, K23, K27 | Chromatin opening | Promoter activation |

| H4 | K5, K8, K12, K16 | Chromatin relaxation | Transcriptional elongation |

| H2A | K5 | Unknown | Context-dependent |

Experimental Implementation for Functional Validation

CRISPR-dCas9-TET1 Targeted Demethylation Protocol

The following protocol adapts the methodology from published studies using CRISPR-dCas9-TET1 for reactivation of the hypermethylated miR-200c promoter in breast cancer cells [4].

Reagent Preparation

- Plasmid Construct: dCas9-TET1 catalytic domain fusion (Addgene #83340 or similar)

- Guide RNA Design: Design two sgRNAs flanking the CpG-rich region of the target promoter:

- sgRNA-1: 5'-GGGGCAGGAGGCGGAGGC-3' (miR-200c promoter example)

- sgRNA-2: 5'-GTCGCCAGCCATCGCAGC-3' (miR-200c promoter example)

- Control Constructs: Include dCas9-only and catalytically dead dCas9-TET1mut as negative controls

Transfection and Processing

- Day 1: Seed MCF-7 or MDA-MB-231 cells in 6-well plates at 2.5 × 10^5 cells/well

- Day 2: Transfect with 2.5 μg dCas9-TET1 and 1.25 μg of each sgRNA plasmid using Lipofectamine 3000

- Day 3: Change media 6-8 hours post-transfection

- Day 4: Harvest cells 48 hours post-transfection for downstream analysis

Validation and Functional Assessment

- Methylation Analysis: Perform bisulfite sequencing on extracted genomic DNA focusing on the target region

- Expression Analysis: Quantify target gene expression (e.g., miR-200c) via RT-qPCR

- Phenotypic Assays:

- MTT assay at 48-72 hours to assess cell viability impact

- Annexin V/PI staining with flow cytometry for apoptosis detection

- Western blotting for downstream targets (e.g., ZEB1/ZEB2 for miR-200c)

Expected Outcomes

Based on published data, effective TET1-mediated demethylation should yield [4]:

- 40-60% reduction in promoter methylation by bisulfite sequencing

- 3-5 fold increase in target gene expression (miR-200c)

- 20-35% reduction in viability in aggressive cell lines (MDA-MB-231)

- 2-4 fold increase in apoptosis compared to controls

CRISPR-dCas9-p300 Targeted Acetylation Protocol

This protocol leverages p300's core catalytic domain (BRPH) for targeted histone acetylation based on structural insights of p300-nucleosome interactions [7].

System Configuration

- Effector Construction: dCas9-p300 core (BRPHZT domain, residues 1048-1836) for optimal nucleosome recognition and catalytic activity

- sgRNA Targeting: Design sgRNAs to position dCas9-p300 at enhancer or promoter regions (150-500bp upstream of TSS for promoters)

- Critical Controls: Include dCas9-only and catalytically inactive HAT domain mutant (autoacetylation site mutations)

Transfection and Analysis

- Day 1: Seed HEK293T or other relevant cells in 6-well plates at 3.0 × 10^5 cells/well

- Day 2: Transfect with 3 μg dCas9-p300 and 1.5 μg sgRNA plasmid using appropriate transfection reagent

- Day 3: Refresh media after 6 hours

- Day 4: Harvest cells at 48-72 hours for molecular analyses

Validation Methods

- Histone Acetylation Mapping:

- ChIP-qPCR/seq using H2BK15ac, H3K27ac, or H4K8ac antibodies

- Compare target vs. non-target regions for specificity assessment

- Transcriptional Output:

- RT-qPCR for target gene expression

- RNA-seq for genome-wide expression profiling

- Chromatin Accessibility: ATAC-seq to confirm chromatin opening at targeted loci

Expected Outcomes

Based on structural and functional studies [7]:

- 5-20 fold increase in H2B acetylation at targeted sites

- 3-8 fold increase in target gene expression

- Increased chromatin accessibility by ATAC-seq

- Synergistic effects when multiple sgRNAs target the same regulatory region

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Epigenome Editing Applications

| Reagent Category | Specific Product | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Effector Plasmids | dCas9-TET1 (CDS) | Targeted DNA demethylation | Include catalytic domain only (residues 1369-2139) for reduced size |

| dCas9-p300 core (BRPH) | Targeted histone acetylation | BRPH domain (1048-1836) provides optimal nucleosome binding | |

| Control Systems | dCas9 alone | Baseline transcriptional effects | Accounts for dCas9 binding-induced effects |

| Catalytic dead mutants | Control for catalytic activity | TET1mut (H1672Y/D1674A), p300mut (Y1394A/D1507A) | |

| Validation Tools | 5hmC-specific antibodies | TET1 activity validation | Distinguish from 5mC in immunostaining |

| H2BK15ac antibodies | p300 activity readout | Primary target of p300 reader-writer mechanism | |

| Bisulfite conversion kits | DNA methylation quantification | Use oxidative bisulfite for 5hmC discrimination | |

| Delivery Reagents | Lipofectamine 3000 | Standard plasmid transfection | Optimize for cell type-specific efficiency |

| Lentiviral packaging system | Difficult-to-transfect cells | Enables stable expression systems | |

| Vincristine | Vincristine | High-purity Vincristine for cancer research. Explore its mechanism as a microtubule polymerization inhibitor. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

| Ifenprodil | Ifenprodil | Ifenprodil is a potent, selective NMDA receptor antagonist targeting the GluN2B subunit. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

Troubleshooting and Optimization Guidelines

Common Challenges and Solutions

Low Editing Efficiency:

- Verify sgRNA binding efficiency using dCas9-GFP and fluorescence quantification

- Test multiple sgRNAs targeting different regions of the regulatory element

- Consider transiently overexpressing wild-type TET1 or p300 to saturate endogenous inhibitors

Off-Target Effects:

- Include multiple control sgRNAs targeting non-functional genomic regions

- Perform whole-genome bisulfite sequencing or ChIP-seq to assess genome-wide specificity

- Use inducible systems to limit duration of effector expression

Variable Phenotypic Outcomes:

- Account for cell type-specific epigenetic backgrounds that influence responsiveness

- Consider the existing chromatin state (H3K4me3-marked promoters respond better to p300)

- Optimize transfection efficiency and measure protein expression directly by Western blot

Applications in Drug Development

The integration of these epigenetic editors into target validation pipelines provides critical functional evidence for:

- Establishing causal relationships between specific epigenetic marks and disease-relevant gene expression

- Prioritizing targets for epigenetic drug development

- Validating mechanisms of action for small molecule epigenetic inhibitors

- Developing patient stratification strategies based on epigenetic markers

These applications accelerate the transition from association studies to functional validation, ultimately supporting more informed decisions in epigenetic drug discovery pipelines.

A central challenge in modern functional genomics is conclusively establishing that observed correlations between specific epigenetic marks, gene expression changes, and phenotypic outcomes represent causal relationships rather than secondary consequences. Traditional pharmacological inhibitors of epigenetic modifiers affect the entire genome, making it difficult to attribute phenotypic changes to the modification of a specific locus. The development of CRISPR-dCas9-based epigenetic editing systems has revolutionized this pursuit by enabling precise, targeted manipulation of individual epigenetic marks at single genetic loci, thereby providing the tools necessary for direct functional validation.

This Application Note details a protocol for employing CRISPR-dCas9-mediated targeted DNA demethylation to establish causality between promoter DNA methylation status, gene reactivation, and subsequent phenotypic consequences. The methodology is framed within a broader research strategy for the functional validation of epigenetically silenced candidate genes, providing a robust experimental framework for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to validate novel epigenetic therapeutic targets.

Conceptual Framework and Key Principles

Epigenetics represents the study of heritable changes in gene expression that do not involve alterations to the underlying DNA sequence [10]. These changes, including DNA methylation and histone modifications, form a critical interface between the genotype and the resulting phenotype, and can be dynamically influenced by environmental factors [10] [11].

- DNA Methylation: In mammals, this typically involves the covalent addition of a methyl group to a cytosine base in a CpG dinucleotide context. Promoter-associated CpG island methylation is frequently associated with transcriptional silencing, as it can lead to chromatin condensation and prevent transcription factor binding [10].

- Establishing Causality: To move beyond correlation, one must demonstrate that directed manipulation of a specific epigenetic mark at a defined locus directly precipitates a change in gene expression, which in turn produces a predictable phenotypic output. The reversible nature of epigenetic marks makes them particularly suitable for such functional interrogation [4].

Featured Methodology: CRISPR-dCas9-TET1 for Targeted Demethylation

The following section outlines a specific application of the dCas9 epigenetic editing system, as demonstrated in a recent study that successfully reactivated the epigenetically silenced tumor suppressor miR-200c in breast cancer cells [4].

Protocol: Targeted Reactivation of miR-200c via Promoter Demethylation

Objective: To reactivate the silenced miR-200c gene in breast cancer cell lines (MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231) by specifically demethylating its promoter using the CRISPR-dCas9-TET1 system and to quantify the subsequent effects on gene expression and tumor-associated phenotypes.

Step 1: sgRNA Design and Plasmid Construction

sgRNA Design:

- Identify the CpG-rich region within the promoter of your target gene (e.g., the miR-200c promoter, particularly the island spanning -343 to -115 bp upstream) [4].

- Design two sgRNAs (gRNA1 and gRNA2) to flank this CpG-dense region. This allows for synergistic demethylation by covering a broader area.

- Use bioinformatic tools like CHOPCHOP to select sgRNA sequences with high on-target efficiency and minimal predicted off-target effects [4].

- Control: Design a non-targeting sgRNA (scrambled sequence) as a negative control.

Plasmid Assembly:

Step 2: Delivery of the CRISPR-dCas9-TET1 System

- Cell Culture: Culture relevant cell lines (e.g., MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231) under standard conditions.

- Co-transfection:

- Transfect cells with the following components:

- Plasmid expressing the dCas9-TET1 fusion protein (catalytically inactive Cas9 fused to the TET1 demethylase domain).

- The constructed sgRNA plasmid(s) (gRNA1, gRNA2, or both).

- Control Groups must include:

- Cells transfected with dCas9-TET1 alone (no sgRNA).

- Cells transfected with a catalytically inactive mutant TET1 construct (dCas9Mut-TET1) with sgRNAs.

- A GFP-expression vector can be co-transfected to monitor and confirm transfection efficiency via fluorescence microscopy [4].

- Transfect cells with the following components:

Step 3: Validation of Targeted Demethylation and Gene Reactivation

DNA Methylation Analysis (48-72 hours post-transfection):

- Extract genomic DNA from transfected and control cells.

- Perform bisulfite sequencing (or a quantitative method like pyrosequencing) on the extracted DNA to analyze the methylation status of the target promoter region.

- Expected Outcome: A significant reduction in methylation levels at the miR-200c promoter in cells co-transfected with dCas9-TET1 and the specific sgRNAs, compared to control groups [4].

Gene Expression Analysis (48 hours post-transfection):

- Extract total RNA.

- Quantify the expression of the target gene (e.g., mature miR-200c) using RT-qPCR.

- Expected Outcome: A significant increase in miR-200c expression, with the highest upregulation observed in cells co-transfected with both gRNA1 and gRNA2, demonstrating a synergistic effect [4].

Step 4: Assessment of Downstream Transcriptional and Phenotypic Effects

Downstream Target Gene Analysis:

- Analyze the expression of known direct targets of the reactivated gene. For miR-200c, this includes genes like ZEB1, ZEB2 (EMT transcription factors), and KRAS.

- Use RT-qPCR or Western blotting to confirm the downregulation of these target proteins.

- Assess the re-expression of epithelial markers like E-cadherin, a hallmark of Mesenchymal-to-Epithelial Transition (MET) [4].

Functional Phenotypic Assays:

- Cell Viability (MTT Assay): Measure cell viability 3-5 days post-transfection. Expect reduced viability in cells with reactivated miR-200c [4].

- Apoptosis Assay (Annexin V/Propidium Iodide Staining): Analyze apoptosis via flow cytometry 72-96 hours post-transfection. Expect a significant increase in the percentage of apoptotic cells, particularly in aggressive cell lines like MDA-MB-231 [4].

The table below summarizes expected quantitative outcomes based on the referenced study [4], providing a benchmark for researchers.

Table 1: Expected Quantitative Outcomes from miR-200c Reactivation

| Experimental Parameter | MCF-7 Cells | MDA-MB-231 Cells | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Promoter Methylation | Marked decrease | Marked decrease | Effect more pronounced from a higher baseline in MDA-MB-231 |

| miR-200c Expression | Significant increase (synergistic with 2 gRNAs) | Significant increase (primarily with gRNA1) | gRNA efficiency is context-dependent; test multiple guides |

| ZEB1/ZEB2 Expression | Downregulation | Downregulation | Confirms miR-200c target engagement |

| E-cadherin Expression | Minimal change | Significant increase | Phenotypic effect is cell context-dependent |

| Cell Viability | Reduced | Reduced | Effect more pronounced in MDA-MB-231 cells |

| Apoptosis Rate | Increase (~1.98% to 10.5%) | Increase (~1.5% to 35.07%) | Stronger effect in more aggressive, mesenchymal-like cells |

Experimental Workflow and Pathway Visualization

Experimental Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow from system design to phenotypic validation.

Signaling Pathway Diagram

This diagram outlines the core signaling pathway reactivated by miR-200c promoter demethylation, demonstrating the link from epigenetic editing to phenotypic outcome.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

A successful CRISPR-dCas9 epigenetic editing experiment requires the following key reagents and controls, the importance of which is emphasized in the cited literature [4] [12] [13].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Controls for dCas9 Epigenetic Editing

| Reagent / Control | Function & Purpose | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9-Effector Fusion | Catalytic core for targeted epigenetic modification. | dCas9-TET1: For targeted DNA demethylation. |

| Target-Specific sgRNAs | Guides the dCas9-effector to the target genomic locus. | 2+ sgRNAs flanking the CpG-rich promoter region. Validated with tool like CHOPCHOP [4]. |

| Delivery Vector | Introduces genetic constructs into cells. | Lentivirus, plasmid, or RNP complexes for primary cells [13]. |

| Methylation Analysis Kit | Quantifies DNA methylation changes at the target locus. | Bisulfite Conversion Kit & Primers for Pyrosequencing. |

| Expression Assay | Measures mRNA/miRNA expression changes post-editing. | RT-qPCR Assay for target gene (e.g., miR-200c) and downstream targets (e.g., ZEB1). |

| Phenotypic Assay Kits | Evaluates functional biological consequences. | MTT Kit (viability) & Annexin V/FITC Kit (apoptosis) [4]. |

| Critical Negative Controls | Distracts specific from non-specific effects. | dCas9-only (no sgRNA): Controls for dCas9 toxicity. Catalytic Mutant (dCas9mut-TET1): Controls for non-catalytic effects [4]. Non-targeting sgRNA: Controls for off-target sgRNA effects. |

| Positive Control | Validates entire experimental system is functional. | sgRNA and assay for a previously validated target locus. |

| S-Isopropylisothiourea hydrobromide | S-Isopropylisothiourea hydrobromide, CAS:4269-97-0, MF:C4H11BrN2S, MW:199.12 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 10-Debc hydrochloride | 10-Debc hydrochloride, CAS:925681-41-0, MF:C20H26Cl2N2O, MW:381.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Technical Considerations and Best Practices

- gRNA Design and Validation: The efficiency of specific gRNAs can vary significantly between cell lines, as observed with gRNA2 having a minimal effect in MDA-MB-231 cells but a significant one in MCF-7 cells [4]. It is critical to design and empirically test multiple gRNAs.

- Cell Context Dependence: Phenotypic outcomes, such as E-cadherin upregulation, can be minimal in some cellular contexts (e.g., MCF-7) but pronounced in others (e.g., MDA-MB-231), highlighting the importance of the initial epigenetic and transcriptional state of the cell [4].

- Specificity Controls: The use of multiple control conditions, including a catalytically dead mutant of TET1 (dCas9Mut-TET1), is essential to confirm that observed effects are due to targeted demethylation and not unrelated to dCas9 binding or cellular stress responses [4].

- Beyond DNA Methylation: This protocol focuses on DNA methylation, but the dCas9 system can be adapted to target other epigenetic marks, such as histone modifications, by fusing dCas9 to histone acetyltransferases (HATs) or histone methyltransferases, forming a broader "CRISPR-Epigenetics Regulatory Circuit" for functional discovery [14].

The advent of catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) has fundamentally expanded the CRISPR toolkit beyond permanent genome editing, enabling precise transcriptional and epigenetic control without altering the underlying DNA sequence [15] [16]. By mutating the RuvC and HNH nuclease domains of Cas9, researchers have created dCas9, which retains its ability to bind DNA target sites specified by a guide RNA (gRNA) but cannot create double-strand breaks [17] [18]. This core protein serves as a programmable platform for recruiting effector domains to specific genomic loci, facilitating reversible gene modulation [15]. This approach presents a paradigm shift from traditional knockout and knockin techniques, which rely on error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR) to make irreversible changes to the DNA sequence [19] [20]. For functional validation research and drug development, the ability to reversibly tune gene expression and epigenetic states offers a more nuanced and physiologically relevant method for probing gene function and identifying therapeutic targets.

Core Advantages of dCas9 Systems

The dCas9 platform offers several distinct advantages over conventional gene editing for functional genomics and pre-clinical research, primarily centered on its reversibility and temporal control.

Reversible Modulation: Unlike traditional knockout/knockin strategies that introduce permanent, heritable changes to the DNA sequence, dCas9-mediated modulation operates at the transcriptional or epigenetic level [15]. The changes induced by systems like CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) or CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) do not alter the genetic code and are often reversible upon removal of the dCas9-effector complex [12] [16]. This is crucial for studying essential genes, modeling transient cellular states, and developing potential therapeutic strategies that require temporary gene expression alteration.

Sequential and Temporal Control: The activity of dCas9 systems can be finely controlled over time using inducible expression systems, such as doxycycline-inducible promoters, or chemically induced proximity systems [15] [18]. This allows researchers to initiate gene modulation at a specific point in a differentiation protocol or disease model, enabling the study of gene function at precise developmental or disease stages. This temporal resolution is difficult to achieve with traditional methods where the genetic change is present from the outset [18].

Precise Epigenetic Engineering: dCas9 can be fused to epigenetic writer and eraser domains, such as DNA methyltransferases (e.g., DNMT3A) or demethylases (e.g., TET1), enabling targeted editing of the epigenome [16] [21]. This allows for the functional validation of specific epigenetic marks at single-gene resolution without the confounding effects of global epigenetic drugs.

Reduced Off-Target and Genotoxic Risks: Since dCas9 systems lack nuclease activity, they do not introduce double-strand breaks (DSBs), thereby eliminating the genotoxic stress associated with the NHEJ and HDR pathways and reducing the risk of chromosomal translocations and large deletions [16] [18].

Multiplexability: The simplicity of designing gRNAs allows for the easy targeting of multiple genomic loci simultaneously. dCas9 can be guided by several sgRNAs to bind to different target sites, enabling the coordinated regulation of entire gene networks or pathways in a single experiment [15] [17].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Gene Modulation Techniques

| Feature | Traditional CRISPR Knockout/Knockin | dCas9-Mediated Modulation |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Cleavage | Yes (Creates DSBs) | No (Catalytically inactive) [16] |

| Change to DNA Sequence | Permanent (Indels or insertions) | None (Epigenetic/transcriptional) [15] |

| Reversibility | Irreversible | Reversible [12] [15] |

| Key Repair Pathway | NHEJ (Knockout) / HDR (Knockin) [20] | N/A |

| Typical Timeline for Mouse Model Generation | 1–2 years [19] | 1–2 months [19] |

| Primary Application | Gene disruption, gene insertion | Gene activation (CRISPRa), repression (CRISPRi), epigenome editing [12] [16] |

Key Experimental Protocols

The following protocols outline core methodologies for implementing reversible gene modulation using the dCas9 system.

Protocol: CRISPR/dCas9-Tet1-Mediated DNA Demethylation

This protocol enables targeted demethylation of specific CpG islands to activate gene expression, using a dCas9-Tet1 fusion system [21].

Step 1: sgRNA Design and Cloning

- Identify Target Sequence: Design sgRNAs to target promoter regions or other regulatory elements rich in CpG sites. The target should be adjacent to a PAM sequence (NGG for SpCas9) [21].

- Clone into sgRNA Scaffold: Anneal and phosphorylate oligonucleotides encoding the sgRNA target sequence. Ligate them into a BsmBI-linearized sgRNA expression vector (e.g., Addgene #84477) [21].

- Validate Clones: Transform the ligation product into Stbl3 competent cells. Screen positive colonies by PCR and Sanger sequencing to confirm correct insertion.

Step 2: Delivery of the dCas9-Tet1 System

- Cell Culture: Maintain relevant cells (e.g., HEK293T, MEFs, or hESCs) in their appropriate culture medium [21].

- Co-transfection: Co-transfect the Fuw-dCas9-Tet1-P2A-BFP plasmid (Addgene #108245) and the constructed sgRNA plasmid into target cells using a suitable transfection reagent (e.g., X-tremeGENE). For difficult-to-transfect cells, use lentiviral delivery.

- Selection and Sorting: After 48-72 hours, harvest cells and use FACS to isolate BFP-positive cells, indicating successful transfection and expression of the dCas9-Tet1 construct [21].

Step 3: Validation of Demethylation Efficiency

- DNA Extraction: Harvest transfected cells and extract genomic DNA using a commercial kit (e.g., DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit) [21].

- Bisulfite Conversion: Treat 500 ng of genomic DNA with the EZ DNA Methylation-Gold kit to convert unmethylated cytosines to uracils.

- Pyrosequencing: Amplify the target region by PCR using bisulfite-converted DNA as a template. Analyze the PCR product by pyrosequencing to quantify the percentage of methylation at individual CpG sites [21].

Protocol: dCas9-Based Transcriptional Repression (CRISPRi)

This protocol describes gene knockdown using dCas9 fused to a transcriptional repressor domain, such as KRAB [16] [18].

Step 1: System Assembly

- Select Repressor Domain: Clone the dCas9-KRAB fusion protein into an expression vector. The KRAB domain recruits repressive complexes that promote histone methylation (H3K9me3), leading to stable gene silencing [16].

- Design sgRNAs: Design sgRNAs to bind the template strand within -50 to +300 bp relative to the transcription start site (TSS) of the target gene to effectively block RNA polymerase [18].

Step 2: Delivery and Induction

- Transduction: Deliver the dCas9-KRAB and sgRNA constructs to cells via lentiviral transduction.

- Doxycycline Induction: If using an inducible system, treat cells with doxycycline (e.g., 1 µg/mL) to initiate expression of the dCas9-effector complex, allowing for temporal control over repression [18].

Step 3: Validation of Knockdown

- RT-qPCR: Isolve total RNA 72-96 hours post-induction and perform reverse transcription followed by quantitative PCR to measure mRNA expression levels of the target gene.

- Western Blot: Analyze protein levels 5-7 days post-induction to confirm functional knockdown.

Visualization of dCas9 Systems

The following diagrams illustrate the core mechanisms and experimental workflow for dCas9-mediated gene modulation.

dCas9 Gene Modulation Mechanisms

Experimental Workflow for DNA Methylation Editing

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for dCas9-Mediated Gene Modulation

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example Items & Sources |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9 Effector Plasmids | Core protein that binds DNA without cleavage; fused to activator, repressor, or epigenetic effector domains. | dCas9-VP64 (Addgene), dCas9-KRAB (Addgene), Fuw-dCas9-Tet1 (Addgene #108245) [16] [21] |

| sgRNA Expression Vectors | Delivers the targeting component; can be cloned into single or multiplexed backbones. | pgRNA-modified (Addgene #84477), pLenti-sgRNA(MS2)_Zeo [22] [21] |

| Delivery Systems | Introduces genetic constructs into target cells; choice depends on cell type and efficiency required. | Lentiviral particles, X-tremeGENE transfection reagent, PiggyBac transposon system [21] |

| Validation Kits | Essential for confirming the success and specificity of the epigenetic or transcriptional modulation. | EZ DNA Methylation-Gold Kit (Zymo Research), PyroMark PCR Master Mix (Qiagen), RT-qPCR reagents [21] |

| Cell Lines | Models for functional validation; can include primary cells, stem cells, or established cell lines. | HEK293T (ATCC CRL-11268), PK15 pig kidney cells, human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) [22] [21] |

| Hki-357 | (E)-N-(4-((3-Chloro-4-((3-fluorobenzyl)oxy)phenyl)amino)-3-cyano-7-ethoxyquinolin-6-yl)-4-(dimethylamino)but-2-enamide | High-purity (E)-N-(4-((3-Chloro-4-((3-fluorobenzyl)oxy)phenyl)amino)-3-cyano-7-ethoxyquinolin-6-yl)-4-(dimethylamino)but-2-enamide for research. This covalent EGFR inhibitor is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnosis or therapeutic use. |

| Lapatinib | Lapatinib, CAS:388082-78-8, MF:C29H26ClFN4O4S, MW:581.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

A Toolkit for Discovery: Methodologies and Real-World Applications in Functional Genomics

Catalytically deactivated Cas9 (dCas9) serves as a programmable DNA-binding scaffold that can be fused with various epigenetic effector domains to manipulate the epigenome without altering the underlying DNA sequence. This technology enables precise functional validation of epigenetic marks in gene regulation, offering significant advantages over global pharmacological epigenetic modifiers that cause genome-wide changes and confounding effects [23] [24]. The three primary dCas9 fusion constructs—dCas9-Tet1CD for DNA demethylation, dCas9-DNMT3A for DNA methylation, and dCas9-p300 for histone acetylation—provide researchers with powerful tools to establish causal relationships between specific epigenetic modifications and gene expression outcomes in functional genomics research and drug discovery.

Molecular Biology of dCas9 Fusion Constructs

dCas9-Tet1CD Demethylation Construct

The dCas9-Tet1CD fusion protein combines the DNA-targeting capability of dCas9 with the catalytic domain of Ten-Eleven Translocation 1 (TET1), an α-ketoglutarate and Fe²âº-dependent dioxygenase. TET1 catalyzes the conversion of 5-methylcytosine (5mC) to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), which can be further oxidized to 5-formylcytosine (5fC) and 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC), initiating the DNA demethylation pathway through base excision repair [23]. This construct enables targeted DNA demethylation when guided to specific genomic loci by sgRNAs. In Arabidopsis, overexpression of TET1cd reduced genome-wide methylation, while targeted demethylation of the hypermethylated NMR19-4 region in the PPH gene promoter increased PPH expression and accelerated leaf senescence [23]. The demethylated state and associated phenotypic effects demonstrated Mendelian inheritance in progeny, indicating stable transgenerational transmission of the edited epiallele [23].

dCas9-p300 Acetylation Construct

The dCas9-p300 fusion links dCas9 to the core catalytic domain of human acetyltransferase p300 (amino acids 1048-1664 or 1284-1673), which acetylates histone H3 at lysine 27 (H3K27ac) [25] [26]. This modification is strongly associated with active gene regulatory elements and enhancers. The dCas9-p300 system functions through a mechanism distinct from conventional dCas9-activators like dCas9-VP64. While VP64 and similar activation domains recruit transcriptional machinery, p300 directly modifies chromatin structure by adding acetyl groups to histones, potentially creating a more permissive chromatin environment for transcription [26]. This system effectively activates genes from promoters, proximal enhancers, and distal enhancers, with studies demonstrating significant transactivation of endogenous genes including IL1RN, MYOD, and OCT4 (POU5F1) [25]. Notably, dCas9-p300 Core induced significantly higher transcription levels than dCas9-VP64 when targeted to the IL1RN and MYOD promoters and successfully activated gene expression from enhancer regions where dCas9-VP64 was ineffective [25].

dCas9-DNMT3A Methylation Construct

The dCas9-DNMT3A fusion couples dCas9 to the de novo DNA methyltransferase DNMT3A, enabling targeted DNA methylation at CpG islands. This construct catalyzes the transfer of methyl groups from S-adenosyl-l-methionine to the C-5 position of cytosine to form 5-methylcytosine (5mC) [27]. DNMT3L is often co-expressed as it enhances de novo methylation activity by forming heterotetramers with DNMT3A [28]. The CRISPR/dCas9-Dnmt3a system has been applied for targeted methylation of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) gene promoter in Alzheimer's disease research, significantly reducing APP mRNA expression, decreasing amyloid-beta peptide levels, and attenuating cognitive impairments in mouse models [27]. Similar approaches have successfully silenced oncogenes like CDKN2A and BACH2 in cancer contexts [27] [28]. Optimization strategies include using the SunTag system to recruit multiple DNMT3A molecules to specific loci, achieving hypermethylation across regions up to 4.5 kb [28].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of dCas9 Fusion Constructs

| Construct | Catalytic Domain | Epigenetic Modification | Primary Effect on Transcription | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dCas9-Tet1CD | TET1 catalytic domain | 5mC → 5hmC → 5fC → 5caC → C (DNA demethylation) | Activation | Functional validation of hypomethylated regions, gene reactivation [23] |

| dCas9-p300 | p300 HAT core domain | Histone H3K27 acetylation | Activation | Gene activation from promoters and enhancers, chromatin opening [25] [26] |

| dCas9-DNMT3A | DNMT3A methyltransferase | Cytosine → 5-methylcytosine (DNA methylation) | Repression | Gene silencing, studying hypermethylation effects, therapeutic repression [27] [28] |

| BAY-678 | BAY-678, CAS:675103-36-3, MF:C20H15F3N4O2, MW:400.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals | |

| NVP-ADW742 | NVP-ADW742, CAS:475489-15-7, MF:C28H31N5O, MW:453.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics of dCas9 Fusion Constructs

| Construct | Target Region | Editing Efficiency | Expression Change | Persistence/Inheritance | Key Experimental System |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dCas9-Tet1CD | NMR19-4 (PPH promoter) | Significant demethylation of hypermethylated region | Increased PPH expression, accelerated leaf senescence | Mendelian inheritance over generations (F1, F2) [23] | Arabidopsis natural accessions |

| dCas9-p300 | IL1RN promoter | N/A | Significant activation vs. dCas9-VP64 (P=0.01924) [25] | Transient (duration dependent on delivery method) | HEK293T cells |

| dCas9-p300 | MYOD distal regulatory region | N/A | Significant activation (P=0.0009); dCas9-VP64 ineffective [25] | Transient | HEK293T cells |

| dCas9-p300 | OCT4 (POU5F1) | 6 of 9 gRNAs increased transcription ≥2-fold [26] | 2-fold or more activation | Transient | HEK293T cells |

| dCas9-DNMT3A | APP promoter | Altered DNA methylation pattern | Significantly reduced APP mRNA | Durable (weeks to months) [27] | APP-KI mouse primary neurons |

| dCas9-DNMT3A | BACH2 locus | Up to 60% CpG methylation [28] | Decreased gene expression | Durable (weeks to months) | HEK293T cells |

| dCas9-DNMT3A | CDKN2A locus | Up to 50% DNA methylation [28] | Decreased gene expression | Durable (weeks to months) | HEK293T cells |

Experimental Protocols

Targeted DNA Demethylation Using dCas9-Tet1CD

Vector Design and Assembly

- Clone the TET1 catalytic domain (Tet1CD) into your dCas9 expression backbone using appropriate restriction sites or Gibson assembly, creating a C-terminal fusion to dCas9

- Design sgRNAs targeting 20-base pair sequences adjacent to the methylation site(s) of interest

- For plant systems, use binary vectors for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation; for mammalian cells, use lentiviral or other appropriate delivery vectors [23]

Delivery and Analysis

- Transform Arabidopsis hypermethylated ecotypes using floral dip method with Agrobacterium carrying the dCas9-Tet1CD construct and sgRNA expression cassette

- Select transgenic plants using appropriate antibiotics or other selection markers

- Analyze methylation status using bisulfite sequencing of the targeted NMR19-4 region

- Evaluate phenotypic consequences (e.g., PPH expression via RT-qPCR, leaf senescence assessment)

- Conduct inheritance studies through genetic crosses and analyze F1 and F2 progeny for stable transmission of demethylated epialleles [23]

Gene Activation Using dCas9-p300

Construct Delivery and Validation

- Co-transfect HEK293T cells with dCas9-p300 Core fusion plasmid and sgRNA expression vectors (typically 4 sgRNAs per target promoter) using your preferred transfection method

- Include controls: dCas9-VP64 for comparison, and catalytically inactive dCas9-p300 Core (D1399Y)

- Harvest cells 48-72 hours post-transfection for analysis

- Validate protein expression via western blot using anti-Cas9 or anti-p300 antibodies [25] [26]

Assessment of Activation

- Quantify gene expression of target genes (e.g., IL1RN, MYOD, OCT4) using RT-qPCR with gene-specific primers

- Assess histone acetylation at target sites using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) with anti-H3K27ac antibody

- For enhancer targeting, analyze expression of genes regulated by the targeted enhancer region

- Compare activation efficiency between dCas9-p300 and conventional activators like dCas9-VP64 [25]

Targeted DNA Methylation Using dCas9-DNMT3A

In Vitro and Cell Culture Applications

- Co-transfect HEK293T cells with dCas9-DNMT3A and sgRNA plasmids targeting the APP promoter region

- For enhanced methylation efficiency, include DNMT3L in the system

- For primary neurons, transfer lentiviral particles containing dCas9-Dnmt3a and APP-targeting sgRNA (e.g., APP -189 sgRNA)

- Culture transfected/transduced neurons for 2 weeks before analysis [27]

In Vivo Application in Mouse Models

- Perform stereotaxic injection of dCas9-Dnmt3a and sgRNA lentivirus into the dentate gyrus region of APP-KI mice (coordinates: AP -2 mm, ML ±1.1 mm, DV -2 mm)

- Inject 10 µl of lentivirus into each hemisphere

- Allow 4 weeks for expression and methylation establishment before behavioral and biochemical analysis [27]

Molecular and Phenotypic Analysis

- Analyze DNA methylation patterns at the APP promoter using bisulfite sequencing

- Quantify APP mRNA levels using RT-qPCR

- Measure amyloid-beta peptide levels and Aβ42/40 ratio via ELISA

- Assess neuronal cell death using TUNEL or other apoptosis assays

- Evaluate cognitive function using behavioral tests (Y-maze, fear conditioning, water maze) [27]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for dCas9 Epigenome Editing

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Purpose | Example Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| dCas9-Tet1CD plasmid | Targeted DNA demethylation | Functional validation of hypomethylated regions, gene reactivation studies [23] | Catalytic domain requires α-ketoglutarate and Fe²⺠cofactors |

| dCas9-p300 Core plasmid | Targeted histone acetylation, gene activation | Activation from promoters and enhancers, chromatin dynamics studies [25] [26] | More effective than dCas9-VP64 for enhancer activation |

| dCas9-DNMT3A plasmid | Targeted DNA methylation, gene silencing | Therapeutic repression, methylation functional studies [27] [28] | Co-expression with DNMT3L enhances efficiency |

| Guide RNA vectors | Target specificity determination | All targeted epigenome editing applications | Multiple sgRNAs often needed for robust effects |

| Bisulfite conversion kit | DNA methylation analysis | Validation of methylation changes at target loci [23] [27] | Essential for assessing DNA methylation editing efficiency |

| H3K27ac antibody | Histone acetylation detection | ChIP validation of dCas9-p300 activity [25] | Confirms targeted chromatin modification |

| Lentiviral packaging system | Efficient delivery to difficult cells | Primary neurons, in vivo applications [27] | Enables transduction of non-dividing cells |

| Off-target prediction tools | Specificity assessment | Cas-OFFinder for identifying potential off-target sites [27] | Critical for experimental validation |

| Oxantel | Oxantel, CAS:36531-26-7, MF:C13H16N2O, MW:216.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| PF-04217903 | PF-04217903, CAS:1159490-85-3, MF:C19H16N8O, MW:372.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Advanced Delivery Methods: RENDER Platform

Recent advances in delivery methods have addressed challenges associated with the large size of CRISPR-based epigenome editors. The RENDER (Robust ENveloped Delivery of Epigenome-editor Ribonucleoproteins) platform utilizes engineered virus-like particles (eVLPs) to transiently deliver CRISPR epigenome editors as ribonucleoprotein complexes into human cells [29]. This system offers several advantages:

- Transient delivery: Minimizes off-target editing risks associated with prolonged editor expression

- Size flexibility: eVLPs can accommodate large epigenome editors that exceed AAV packaging capacity

- Versatility: Successfully delivered CRISPRi, DNMT3A-3L-dCas9, CRISPRoff, and TET1-dCas9 editors

- Broad applicability: Effective across various human cell types, including primary T cells and stem cell-derived neurons

- Durability: DNMT3A-3L-dCas9 and CRISPRoff eVLPs maintained robust epigenetic silencing for at least 14 days post-treatment [29]

The RENDER platform enables reversible epigenome editing, with TET1-dCas9 eVLPs successfully reversing CRISPRoff-mediated repression of CLTA-GFP in ~6% of treated cells, with reactivation remaining stable for 15 days [29].

CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) represents a powerful approach in functional genomics, enabling researchers to precisely upregulate endogenous gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence. These systems utilize a catalytically inactive Cas9 (dCas9) fused or recruited to transcriptional activators, which are guided to specific genomic loci by single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs). This technology has revolutionized gain-of-function studies by allowing targeted transcriptional modulation within native chromosomal contexts, preserving natural splice variants, regulatory feedback, and epigenetic states that are often disrupted by traditional cDNA overexpression. For functional validation research, CRISPRa provides a more physiologically relevant method for establishing gene function and modeling gene dosage effects, making it particularly valuable for drug target identification and validation [30] [31].

The evolution of CRISPRa systems has progressed from first-generation constructs to increasingly sophisticated architectures that enhance activation potency. The fundamental dCas9-VP64 system serves as the foundation, while subsequent developments like the MS2-MCP-scaffolded VP64 and Synergistic Activation Mediator (SAM) systems employ multi-component recruitment strategies to achieve stronger transcriptional activation. Understanding the comparative advantages, limitations, and optimal applications of these systems is essential for their effective implementation in epigenetic editing and functional validation research [32] [31].

Comparative Analysis of CRISPRa Systems

System Architectures and Activation Mechanisms

dCas9-VP64: This first-generation system employs dCas9 directly fused to a VP64 activator domain (a tandem tetramer of the VP16 peptide). It represents the simplest CRISPRa architecture, where the dCas9-VP64 fusion protein is recruited to target sites via sgRNAs, bringing the VP64 domain to promote transcription initiation. While simple in design, its activation potency is limited due to the delivery of only a single activator complex per dCas9 molecule [32] [31].

MS2-MCP-scaffolded VP64: This enhanced system incorporates an engineered sgRNA containing MS2 RNA aptamers in its stem loop. These aptamers recruit MCP (MS2 coat protein) fused to additional VP64 domains. This creates a dual-recruitment mechanism where activation comes from both the dCas9-VP64 fusion and the MS2-MCP-VP64 recruits, significantly enhancing the local concentration of activators at the target locus without requiring larger dCas9 fusion proteins [32].

SAM (Synergistic Activation Mediator): The SAM system represents a third-generation CRISPRa platform that further amplifies the recruitment strategy. It utilizes three components: (1) dCas9-VP64; (2) an engineered sgRNA containing two MS2 aptamers; and (3) MCP fused to a heterologous activation domain composed of p65 and HSF1 (often abbreviated as MPH). This creates a three-pronged activation complex that recruits VP64, p65, and HSF1 activation domains simultaneously, generating a synergistic effect that drives robust transcriptional activation [32] [33].

Table 1: Comparative Architecture of CRISPRa Systems

| System | Core Components | Activation Domains | Recruitment Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| dCas9-VP64 | dCas9-VP64 fusion protein | VP64 | Direct fusion of VP64 to dCas9 |

| MS2-MCP-scaffolded VP64 | dCas9-VP64 + sgRNA-MS2 + MCP-VP64 | VP64 (multiple copies) | dCas9 fusion + MS2 aptamer-mediated recruitment |

| SAM | dCas9-VP64 + sgRNA-MS2 + MCP-p65-HSF1 | VP64 + p65 + HSF1 | dCas9 fusion + MS2 aptamer-mediated recruitment of heterologous activators |

Performance and Efficiency Comparison

Quantitative assessments reveal significant differences in activation potency across these systems. Direct comparisons show that MS2-MCP-scaffolded VP64 consistently outperforms simple dCas9-VP64 fusions across multiple endogenous gene targets. The SAM system typically demonstrates the highest activation efficacy, achieving substantially greater fold-increases in target gene expression compared to both dCas9-VP64 and MS2-MCP-scaffolded VP64 systems [32].

The superior performance of SAM stems from its ability to recruit diverse activation domains that work synergistically. The combination of VP64, p65, and HSF1 engages multiple facets of the transcriptional machinery, leading to more robust and sustained gene activation. However, this enhanced potency comes with practical limitations, including increased cytotoxicity associated with expressing the potent p65-HSF1 activator fusion, which can lead to cell death and confounding selection pressures in experimental systems [33].

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of CRISPRa Systems

| System | Activation Efficiency | Cytotoxicity Concerns | Ideal Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| dCas9-VP64 | Moderate (2-10 fold) | Low | Basic gene activation, sensitive cell models |

| MS2-MCP-scaffolded VP64 | High (10-50 fold) | Low to moderate | Balanced performance needs |

| SAM | Very high (50-1000+ fold) | Significant | Maximal activation, robust cell lines |

Recent advances in CRISPRa have highlighted the importance of condensate dynamics in effective gene activation. Systems that form liquid-like transcriptional condensates with high dynamicity and liquidity demonstrate superior activation compared to those forming solid-like condensates that sequester co-activators. This understanding provides a mechanistic framework for why systems with optimized activator multiplicity, such as SunTag3xVPR, can outperform systems with excessive scaffolding [34].

Application Notes for Functional Validation Research

System Selection Guidelines

Choosing the appropriate CRISPRa system depends on multiple factors, including the target gene's baseline expression, chromatin environment, and the desired level of activation. For genes with low basal expression or those embedded in repressive chromatin, the SAM system often provides sufficient activation potency. However, researchers must carefully consider the cellular context, as the cytotoxicity associated with strong activators like p65-HSF1 can limit application in sensitive systems such as primary cells [33].

For functional validation in drug discovery, establishing a dose-response relationship between gene activation and phenotypic outcome is crucial. The MS2-MCP-scaffolded VP64 system often provides an optimal balance between potency and practicality for such applications. When working with silent loci or highly methylated gene promoters, combining CRISPRa with epigenetic modifiers such as TET1 can enhance activation by remodeling the chromatin landscape to a more permissive state [35].

Addressing Technical Challenges

Cytotoxicity Management: The pronounced cytotoxicity of potent activator domains like those in the SAM system presents a significant challenge. Strategies to mitigate this include using inducible expression systems for activators, employing lower-efficacy promoters to reduce expression levels, and implementing careful titration experiments to identify the minimal effective dose. When using lentiviral delivery, toxicity can manifest as low viral titers during production and cell death post-transduction, potentially confounding experimental results through selective pressure [33].

Multiplexed Activation: A key advantage of CRISPRa systems is their ability to activate multiple genes simultaneously through delivery of multiple sgRNAs. For the MS2-MCP-scaffolded VP64 and SAM systems, multiplexing gRNA expression significantly enhances endogenous gene activation, with some studies reporting levels comparable to SAM with a single gRNA. This capability is particularly valuable for validating multi-gene pathways or modeling polygenic diseases in functional validation research [32].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Lentiviral Delivery of SAM System for Endogenous Gene Activation

Principle: This protocol describes the implementation of the three-component SAM system for robust gene activation in mammalian cells, suitable for functional validation studies.

Reagents and Materials:

- Lenti-dCas9-VP64 (Addgene #61425)

- Lenti-MPH (MS2-p65-HSF1) (Addgene #89308)

- Lenti-sgRNA(MS2) backbone (Addgene #89308)

- HEK293T packaging cells

- Polyethylenimine (PEI) transfection reagent

- Target cells of interest

- Puromycin and hygromycin selection antibiotics

Procedure:

- sgRNA Design and Cloning: Design sgRNAs targeting regions -200 to -50 bp upstream of the transcription start site (TSS) of your target gene. Clone annealed sgRNA oligos into the BsmBI-digested lenti-sgRNA(MS2) backbone via Golden Gate assembly.

- Lentivirus Production:

- Day 1: Seed HEK293T cells in 10 cm plates to reach 70-80% confluency the next day.

- Day 2: Transfect with 3.3 µg transfer vector (sgRNA, dCas9-VP64, or MPH), 2.5 µg psPAX2, and 1.2 µg pMD2.G using PEI transfection reagent.

- Day 3: Replace medium with fresh DMEM + 10% FBS.

- Day 4: Collect viral supernatant, filter through 0.45 µm membrane, and concentrate if necessary.

- Cell Transduction:

- Day 1: Seed target cells at 30-50% confluency.

- Day 2: Transduce with dCas9-VP64 lentivirus in the presence of 8 µg/mL polybrane.

- Day 4: Begin selection with 2 µg/mL puromycin for 5-7 days.

- Day 7: Transduce selected cells with MPH lentivirus.

- Day 9: Begin selection with 100 µg/mL hygromycin for 5-7 days.

- Day 12: Transduce with sgRNA lentivirus.

- Day 14: Begin selection with appropriate antibiotic for the sgRNA vector.

- Validation and Analysis:

- Day 17: Harvest cells for RNA extraction and qRT-PCR analysis of target gene expression.

- Day 18: Perform functional assays based on the expected phenotypic outcomes.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- Low activation efficiency: Optimize sgRNA positioning relative to TSS; test multiple sgRNAs per gene.

- High cytotoxicity: Titrate viral MOI to minimize activator expression while maintaining efficacy; consider inducible systems.

- Variable results: Ensure stable polyclonal populations by maintaining selection antibiotics throughout experiments.

Protocol 2: MS2-MCP-scaffolded VP64 for Multiplexed Gene Activation

Principle: This protocol enables simultaneous activation of multiple genes using the MS2-MCP-scaffolded VP64 system, ideal for pathway validation studies.

Reagents and Materials:

- dCas9-VP64 expression plasmid

- MCP-VP64 expression plasmid

- sgRNA expression vector with MS2 aptamers

- Lipofectamine 3000 or similar transfection reagent

- Target cells

Procedure:

- Multiplexed sgRNA Design: Design 3-5 sgRNAs per target gene, focusing on regions within 500 bp upstream of TSS. For multiplexing, clone up to 6 sgRNAs as tandem tRNA-sgRNA arrays using BsmBI restriction sites.

- Transient Transfection:

- Day 1: Seed cells in 12-well plates to reach 70-80% confluency at transfection.

- Day 2: Prepare transfection complex with 500 ng dCas9-VP64, 500 ng MCP-VP64, and 750 ng sgRNA plasmid(s) per well using Lipofectamine 3000 according to manufacturer's protocol.

- Day 3: Replace with fresh medium.

- Day 4: Harvest cells for analysis or continue with functional assays.

- Validation:

- Quantify mRNA expression of target genes via qRT-PCR 48-72 hours post-transfection.

- Assess protein expression changes via Western blot or immunofluorescence 72-96 hours post-transfection.

- Perform functional assays relevant to the activated pathway (e.g., proliferation, differentiation, reporter assays).

Optimization Tips:

- For difficult-to-activate genes, include multiple sgRNAs targeting both promoter and potential enhancer regions.

- When activating multiple genes in a pathway, balance the sgRNA ratios to achieve physiological expression levels.

- Include non-targeting sgRNA controls and target known easily-activated genes (e.g., housekeeping genes) as positive controls.

Figure 1: CRISPRa Experimental Workflow. This flowchart outlines the key decision points and steps in implementing CRISPRa systems for functional validation studies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for CRISPRa Implementation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| dCas9 Activators | dCas9-VP64, dCas9-VPR, dCas9-p300 | Core DNA-binding moiety fused to activation domains | VP64 provides basic activation; VPR offers enhanced potency |

| sgRNA Scaffolds | MS2, PP7, com RNA aptamers | Recruit additional activator proteins to target locus | MS2 most commonly used for MCP recruitment |

| Recruited Activators | MCP-VP64, MCP-p65-HSF1 (MPH), PCP-p65-HSF1 (PPH) | Secondary activation components | p65-HSF1 fusions highly potent but cytotoxic |

| Delivery Vectors | Lentiviral, piggyBac, episomal plasmids | Introduce CRISPRa components into cells | Lentiviral enables stable integration; episomal less toxic |

| Selection Markers | Puromycin, hygromycin, blasticidin, GFP | Enrich for successfully transduced cells | Multiple markers needed for multi-component systems |

| Validation Tools | qPCR primers, antibody panels, functional assay kits | Confirm target gene activation and phenotypic outcomes | Essential for measuring system efficacy |

| 1,3-PBIT dihydrobromide | 1,3-PBIT dihydrobromide, MF:C12H20Br2N4S2, MW:444.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| PTP Inhibitor IV | PTP Inhibitor IV, CAS:329317-98-8, MF:C26H26F6N2O4S2, MW:608.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The strategic selection and implementation of CRISPRa systems is paramount for successful functional validation research. While the SAM system offers maximum activation potency, its associated cytotoxicity may limit utility in sensitive experimental systems. The MS2-MCP-scaffolded VP64 system represents a robust middle ground, providing substantial activation with more manageable toxicity profiles. The foundational dCas9-VP64 system remains valuable for applications requiring moderate gene upregulation or when working with cytotoxicity-sensitive models.

As CRISPRa technology continues to evolve, emerging considerations such as transcriptional condensate dynamics and activator-induced cytotoxicity will inform the development of next-generation systems. By matching system capabilities to experimental requirements and carefully managing technical challenges, researchers can effectively leverage these powerful tools for comprehensive functional validation in epigenetic editing and drug development workflows.

CRISPR-dCas9 epigenetic editing has emerged as a transformative tool for functional genomics, enabling researchers to directly manipulate gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence. By fusing a catalytically inactive Cas9 (dCas9) to epigenetic effector domains, this technology allows for precise, programmable modification of the epigenome—including DNA methylation and histone modifications—to establish causal relationships between epigenetic states, gene transcription, and cellular phenotypes [36] [37]. This approach provides powerful capabilities for target deconvolution and disease modeling by moving beyond correlation to demonstrate causation in epigenetic regulation.

The reversibility of epigenetic modifications makes them particularly attractive for therapeutic development, and CRISPR-dCas9 systems offer unprecedented precision for manipulating these dynamic marks [36] [38]. Unlike traditional CRISPR-Cas9 that creates DNA double-strand breaks, dCas9-based epigenetic editors provide a reversible, non-mutagenic means of controlling gene expression, making them especially valuable for modeling disease states and validating therapeutic targets in functional genomics research [37].

Key Applications in Target Deconvolution and Validation

Reactivating Silenced Tumor Suppressors in Cancer Models

A primary application of CRISPR-dCas9 epigenetic editing in functional genomics involves reactivating epigenetically silenced tumor suppressor genes to validate their functional roles in cancer progression. In a recent study investigating breast cancer mechanisms, researchers employed a CRISPR/dCas9-TET1 system to specifically demethylate and reactivate the promoter of miR-200c, a microRNA known to regulate epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and metastasis [4]. This targeted approach enabled precise deconvolution of miR-200c's specific functional contributions within the complex regulatory network of breast cancer progression.

The experimental workflow demonstrated that targeted demethylation of the miR-200c promoter using two specifically designed gRNAs resulted in synergistic reactivation of miR-200c expression, leading to downstream suppression of key EMT-related transcription factors ZEB1 and ZEB2, as well as the oncogene KRAS [4]. This epigenetic reactivation functionally impaired tumor cell aggressiveness, as evidenced by reduced cell viability and increased apoptosis in breast cancer cell lines—providing direct causal evidence for miR-200c's role as a metastasis suppressor and validating its potential as a therapeutic target [4].

Dissecting Histone Modification Functions in Development

Beyond DNA methylation, CRISPR-dCas9 systems have been deployed to elucidate the functional consequences of specific histone modifications in developmental processes. In plant developmental biology, researchers designed a CRISPR-dCas9-based tool to specifically remove the repressive H3K27me3 mark from the CUP SHAPED COTYLEDON 3 (CUC3) boundary gene in Arabidopsis [39]. By recruiting the JMJ13 H3K27me3 demethylase catalytic domain to the CUC3 locus via a dCas9-SunTag system, they achieved targeted demethylation that induced ectopic transcription and altered gene expression patterns [39].

This precise epigenetic manipulation resulted in measurable phenotypic changes including altered leaf morphology and compromised meristem integrity, directly establishing the causal role of H3K27me3-mediated repression in developmental outcomes [39]. This approach provides a powerful template for deconvoluting the specific functions of histone modifications in developmental gene regulation across diverse biological systems.

Modeling Neurological Disorders through Epigenetic Manipulation

CRISPR-dCas9 epigenetic editing platforms show significant promise for modeling neurological disorders influenced by epigenetic dysregulation. Researchers have developed protein-based delivery systems using virus-like particles (VLPs) to deliver CRISPR epigenome editors to neurons derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [37]. This approach has enabled targeted epigenetic silencing of disease-relevant genes such as tau, which forms neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer's disease [37].

The platform demonstrates the versatility of dCas9 systems for both gene silencing (through fusion to DNMT3A DNA methyltransferase) and gene reactivation (through fusion to TET demethylase), providing a bidirectional tool for modeling disease states associated with both epigenetic silencing and inappropriate gene activation [37]. The protein-based delivery method offers particular advantages for neuronal applications, where traditional delivery methods face challenges, and provides transient editing activity that may enhance safety profiles for functional genomics research [37].

Quantitative Data from Key Studies

Table 1: Quantitative Outcomes of CRISPR-dCas9-Mediated Epigenetic Editing in Functional Genomics Studies

| Study Model | Epigenetic Editor | Target Gene/Locus | Editing Efficiency | Functional Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231) [4] | dCas9-TET1 | miR-200c promoter | Significant reduction in promoter methylation; ~35% apoptosis (vs. 1.5% in controls) | Reduced cell viability; Downregulation of ZEB1, ZEB2, KRAS; Increased E-cadherin |

| Breast cancer cells (MCF-7) [4] | dCas9-TET1 | miR-200c promoter | Marked decrease in methylation; ~10.5% apoptosis (vs. 1.98% in controls) | Reduced cell viability; Downregulation of ZEB1, ZEB2; Minimal E-cadherin change |

| Arabidopsis plants [39] | dCas9-JMJ13 (H3K27me3 demethylase) | CUC3 boundary gene | Specific H3K27me3 removal; Ectopic transcription induction | Altered leaf morphology (smaller, rounder leaves); Compromised meristem integrity |

| Bladder cancer model [40] | dCas9-SAM | Multiple target genes | Efficient multi-gene activation with minimal off-target effects | Inhibited proliferation and migration; Promoted apoptosis in cancer cells |

Table 2: Comparison of Epigenetic Effector Domains for CRISPR-dCas9 Applications

| Effector Domain | Epigenetic Modification | Effect on Transcription | Key Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|